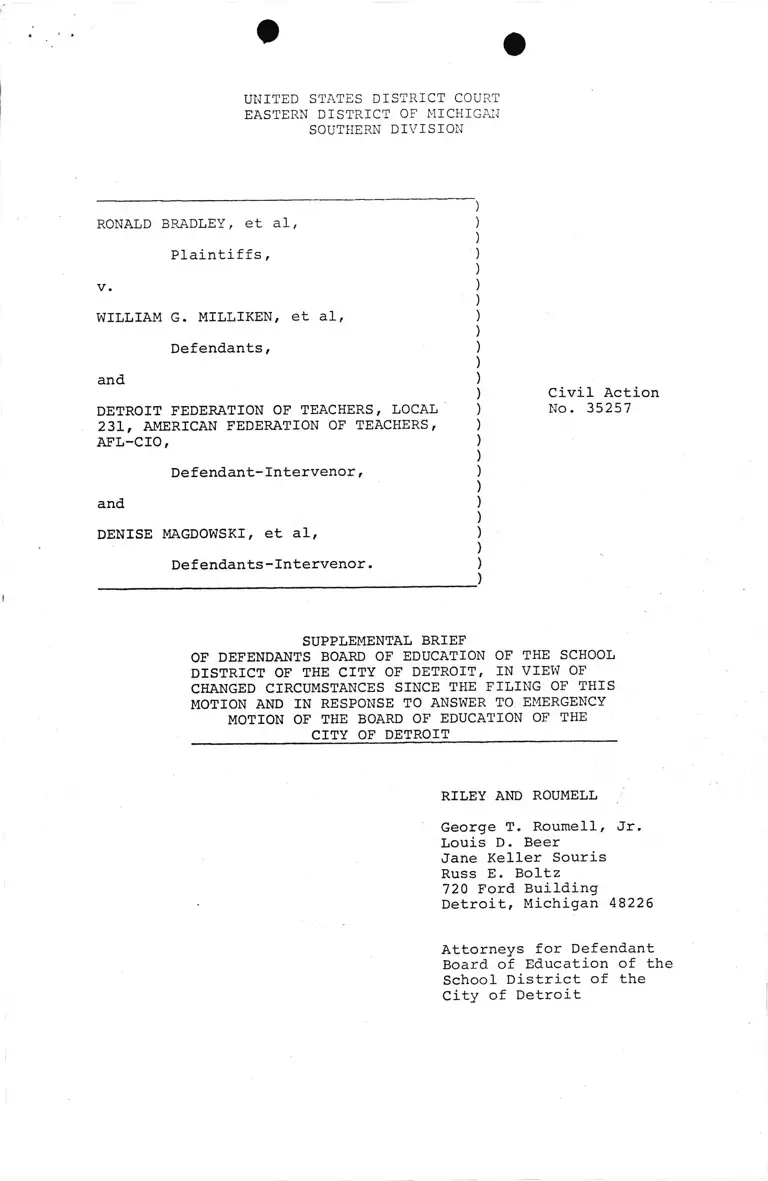

Supplemental Brief to Motion and in Response to Answer to Emergency Motion

Public Court Documents

December 8, 1972

23 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Supplemental Brief to Motion and in Response to Answer to Emergency Motion, 1972. dde4b4b8-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c4945e15-6685-41d1-a596-b7400e5edb1c/supplemental-brief-to-motion-and-in-response-to-answer-to-emergency-motion. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

)

RONALD BRADLEY, et al, )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

v. )

)

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al, )

)

Defendants, )

)

and )) Civil Action

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL ) No. 35257

231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, )

AFL-CIO, )

)Defendant-Intervenor, )

)

and )

)

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al, )

)

Defendants-Intervenor. )

)

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

OF DEFENDANTS BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DETROIT, IN VIEW OF

CHANGED CIRCUMSTANCES SINCE THE FILING OF THIS

MOTION AND IN RESPONSE TO ANSWER TO. EMERGENCY

MOTION OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY OF DETROIT ___________

RILEY AND ROUMELL

George T. Roumell, Jr.

Louis D. Beer

Jane Keller Souris

Russ E. Boltz

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Defendant

Board of Education of the

School District of the

City of Detroit

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

)RONALD BRADLEY, et al, )

)Plaintiffs, )

)v. )

)WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al, )

)Defendants, )

)and )

)DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL )

231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, )

AFL-CIO, )

)Defendant-Intervenor, )

)and )

)DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al, )

)Defendants-Intervenor. )

________ _________________________ __________________)

Civil Action

No. 35257

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

OF DEFENDANTS BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DETROIT, IN VIEW OF

CHANGED CIRCUMSTANCES SINCE THE FILING OF THIS

MOTION AND IN RESPONSE TO ANSWER TO EMERGENCY

MOTION OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY OF DETROIT

INTRODUCTION

Events occurring since the Detroit Board filed its Motion

on November 22, 1972, compel your Movant to further brief the

issues before this Court. Furthermore, repeated and gross mis

statements of the law contained in the Response of the Attorney

General also mandate reply.

It should be noted at the outset that much of the thrust

of the Attorney General's pleadings has been rendered moot by

action of the Detroit Board on December 5, 1972, at which time

the Detroit Board rescinded its Motion to close on December 22,

1972. Although not filed until Thursday, December 7, 1972, the

Attorney General's pleading was apparentlv written before Tues

day, for it is largely devoted to an argument against such a

closing which is now moot. The Detroit Board, in view of some

indication of legislative support, does intend to remain open as

long as it can.

Much of the rest of the pleadings of the Attorney General

are devoted to issues which are substantially irrelevant; namely,

an attempt to assess blame for the current financial predicament

of the Detroit schools. In the eyes of the Attorney General,

apparently the School Board is spendthrift, the electors are

miserly, and the employees are venal. It is apparently the fault

of everybody handy that the Detroit schools are threatened with

closing except the officers of the State of Michigan, even though

it is the State which is charged with providing a system of

education.

The fact that the State audit,surrounded with so much

innuendo in the Attorney General's pleading,showed no wrongdoing

and almost minimal waste in the Detroit schools, except as

necessary to decentralization programs mandated by State statute;

the fact that Detroit teachers received some pay raises in the

past five years pursuant to the State statute which requires

collective bargaining, and the facts of poverty and old age

which doomed to failure the monumental efforts of the Detroit

Board to pass millage, are not really important here. Nor, in

view of the many denigrations of the Detroit Board attempted

by State Defendants throughout this litigation is another one

very painful. What is relevant here is the Constitutional

rights of school children. Detroit school children were not

on the Attorney General's list of those to be assigned blame,

yet it is their Constitutional rights which will be destroyed

if no relief is forthcoming. That is what is imoortant,

Vnot bickering about blame among the parties.

Similarly not in point are the arguments of the Attorney

General which assume that the Detroit Board is attempting to

immediately rip Eighty Million Dollars off of the general funds

of the State. This is not the case, nor has it ever been the

case. The Board wishes that its schools be operated in a fashion

consistent with the Constitution and the previous Order of this

Court on July 7, 1972. The Board has asked by this motion only

that the Court order State Defendants to come forward with a plan

for Constitutional operation of the schools, in the event that

the legislature fails to do so. If, as the Attorney General

tells us, it is certainly the case that the legislature will act,

then that plan will never be used and State Defendants will not

be harmed at all. However, if the legislature fails in its

responsibility, then this Court will be in a posture, by granting

i .

this relief to insure that Detroit school children receive

their Constitutional rights and that the previous mandate of

this Court will be obeyed. Amazing as it seems so late in

this litigation, the pleadings of the Attorney General make it

obvious that it is necessary for this Court to make clear to

State officials that it has the power and the duty and the will

to' enforce the Constitution of the United States of America,

1/ Perhaps these arguments of the Attorney General are

of some significance, though, in that they indicate the

tenor of thought of State Defendants toward Detroit

school children and the Constitutional jeopardy they

face. If/ indeed, this is the position of State

Defendants that it is all Detroit's fault, it casts

a definite pall on the rosy predictions of the Attorney

General that it is a sure thing that the legislature

will respond in a positive fashion.

and that no exception to the Supremacy Clause exists for

elected officials of the State of Michigan. This is all we ask.

I.

THIS COURT HAS THE POWER TO ACT TO ENFORCE THE

CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

Throughout the pleadings of the Attorney General is

a constant theme with several variations; he says that this

Court does not have the power to prevent the flouting of its

own previous Order of July 7, 1972 (which the Attorney General

never appealed),nor to prevent a Constitutional and educational

catastrophy in the City of Detroit. This is simply not so.

Perhaps it would be simplest to deal seriatim with the several

variations of this theme.

A. The Argument That None But The Legislature

Can Prevent A Violation Of The Constitution

In This Matter Is Patently False Under Both

State and Federal Law.

The Attorney General repeats here an argument made

throughout the trial of this case, as well as at the hearings

on the July 7, 1372, Order. The consistency with which it has

been made is equaled only by the consistency with which it has

been rejected. In his Findings of Facts and Conclusions of Law

issued on June 14, 1972, Judge Roth, speaking of State Defendants,

noted,

"...their stubborn insistence that under

their self-serving and therefore, self

limiting view of their powers, they were

free to ignore the clear Order of this Court

and abdicate their responsibility vested in

them by both the Michigan and Federal

Constitution for supervision of public educa

tion and equal protection for all citizens."

June 14, 1972, Findings of Fact, p.5.

-4-

As it appears from his pleadings, the Attorney General

is still unwilling to cooperate with the Court, and that State

Defendants care more about denying their responsibilities than

the Constitutional rights of the school children citizens of the State.

It would perhaps be helpful to suggest several remedies which

even under their "self-serving and therefore, self-limiting

view of their power" are well within the authority of State agents

to carry out. We hasten to add in listing these possible remedies,

that many of them are as a practical matter repugnant to the

Detroit Board. We do not advocate them as the best solution.

We offer them only to show that remedies do exist well within

the power of these Defendants and other State agents available

to the jurisdiction of this Court. Certainly State Defendants,

whose knowledge and wisdom regarding the implementation of State

government is presumably second to none, can do better.

1. This Court could order, failing action of the

State legislature, that all schools in the State of

Michigan be closed at the same time the Detroit

schools are forced to close. This solution has

nothing whatsoever to recommend it, except that it

does provide equal protection of the law and

facilitates the solution of practical problems of

implementation of the desegregation remedy of the

Court. It clearly does provide a Constitutional

remedy. The application of the State statute

providing for 180 days of instruction would clearly

be applied in an unconstitutional fashion if it

were not to be enforced with regard to the State's

largest school system, which contains more than

one-eighth of the public school students of the

State. Once the State undertakes to provide

-5-

f #

education, it must provide it evenhandedly to all.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 347

US 483 (1954); Hall v. St.Helena Parish School

Board, 197 F .Supp 649 (Ed La 1961),_______affd. 287

F.2d ___376 (CA 5 1961).

Furthermore, this remedy meets every objection

and protestation of lack of authority made by the

Attorney General, even if they are accepted at face

value. It requires no expenditures of additional

public funds. It orders no State officials to do

anything; instead, it is merely a prohibitive

injunction against local school districts which are

without question within the jurisdiction of this

Court. It is not in any way a suit against the

State; it is simply a prohibition against the

operation of a law which would be unconstitutional

if applied in the event that Detroit schools are

closed.

Even under the most stringently "self

limiting" view of the powers of State officials,

they surely are capable of refraining from action.

2. This Court could order, failing legislative

action, that the various school districts of the

State, or perhaps those within the metropolitan

desegregation area, pay over to the State Treasurer

sufficient State aid funds to fund the Detroit

school district for the remainder of the school

year. The Attorney General is correct in pointing

out that Michigan law does not specifreally

provide for the Governor, the State Board of Education,

-6-

or the Attorney General, to expend funds for direct

educational purposes. However, the curious con

clusion which he infers from this point is that

nobody may expend such funds. Yet, obviously, the

funds are expended, and not by the legislature; no

school teacher in Michigan receives a pay check signed

by legislators.

Obviously, these State agents which expend State

funds for public education are local school districts

which the Attorney General admits at page 28 of his

Brief,are agents of the State. As these districts

act under color of State law, performing a State

function, they may be ordered to do so in a Constitu

tional fashion; that is, in a fashion which provides

for equal protection for all school children. Indeed,

in the long line of cases cited by the Detroit Board

in its initial brief at page 10, and in the same cases

as cited by the Court (June 14, 1972, Conclusions of

Law, p.32) that is exactly what courts have routinely

done when closings of school were threatened.

The major argument advanced against such action

by the Attorney General is that it would be disruptive,

and would produce chaos and inequity. How it would

be more chaotic, disruptive and inequitable to provide

that all school children receive the same number of

days of schooling rather than that one-eighth of the

children be totally deprived of education after

mid-March, is beyond the comprehension of the Detroit

Board. Admittedly, such a remedy is highly undesirable;

Defendant Detroit Board in no way seeks to have the

rights of Detroit school children vindicated at the

-7-

expense of the educational opportunities of other

school children. Yet, such a result would meet the

Constitutional mandate of equal protection and the

responsibility for the fact that it was bad public

policy would not rest with this Court, but the State

legislature which condoned the Constitutional

violation in the first place and failed to remedy it.

3. State Defendants,under existing State statute,

may provide for the dissolution of the Detroit School

District and the attachment of its several parts to

adjacent school districts. In his litany of various

previous legislative remedies for financial problems,

the Attorney General neglected to mention that several

of these statutes provided for the dissolution of

insolvent school districts, with their territory

being attached to adjacent districts. See particu

larly Section 6a of 1968 PA 32, MSA 15.1916 (106a),

yet seq.

While the Attorney General is correct in noting

that that statute has expired, the statute at M.C.L.A.

340.461, et; seq, MSA 15.3461 has not. That statute

provides that the Intermediate Board of Education may

detach up to ten per cent of the territory of any

school district and attach it to another contiguous

district, without vote of either the attaching or

2/ Note also Section 15a of that Act which mandated

the State Board of Education to re-organize such

districts, "so as to provide the most equitable

educational opportunity for all of the students

of the re-organized district."

-8-

detaching district. M.C.L .A. 340.467 provides that

such action may be appealed to the State Board of

Education and "the State Board of Education is

hereby empowered to consider such appeals and to

confirm, modify or set aside the order of the

county Board of Education or the joint boards and

its action on any such appeal shall be final."

See School District No. 3, Mt. Haley Tp. v. State

Board of Education, 364 Mich. 160, and School

District of City of Lansing v. State Board of

Education, 367 Mich. 591.

Thus, it is within the power of State Defen

dants, if the legislature defaults, to dismember the

Detroit district and attach its severed parts to

ten or more contiguous and solvent districts, thus

providing sufficient revenue to continue the operation

of schools for Detroit children. Once again, the

Detroit Board advocates no such remedy, but the power

to affect it is there.

The above schemes, distasteful as they may be, vividly

demonstrate that even an unreguired slavish adherence to Michigan

statutes, and an equally dedicated ignorance of the Federal law

which does allow the contravention of such statutes to meet

Constitutional purposes will not prevent the State agents from

acting to prevent the violation of the clear order of this Court.

These horribles are not necessary, for the law does allow the

simple direct order which does make sense in the absence of

legislative action; namely, ordering the State Treasurer to

disburse the funds necessary to operate the Detroit schools,

absent fulfillment of this responsibility by the State legis

lature.

-9-

The argument of the Attorney General assumes that powers

must be exercised here which simply do not need to be exercised.

All that is required is that the Treasurer issue his warrant.

He does not have to revamp appropriations; he need not tamper

with the State Budget; he has no responsibility to realign other

State priorities to cover this shortage. As the Attorney General

points out, none of that is his job.

What, then, of other State programs for which money was

allocated? The answer is, of course, that these decisions should

be made by the legislature. The situation would be precisely

that created if the State Treasurer's estimate of the revenues

he expects to receive for a given year proved to be incorrect.

The State Treasurer need only report to the legislature and the

Bureau of the Budget that the revenues in the general fund are

not sufficient to cover the budgetary appropriations made by

the legislature, and the legislature may respond by either, in

its judgment, modifying appropriations to cover this shortfall,

or levying taxes to raise new revenue. Those decisions are,

of course, legislative decisions that need not be the concern

of this Court as long as they are made in a Constitutional fashion

We need go no further than this District and this year

to find a case which forms a striking parallel. In Dunnell v.

Austin,344 F Supp 210 (ED Mich.1972), Judge Keith considered

the Constitutionality of Michigan's Congressional districts.

It was determined by stipulation of the parties that the current

districts were unconstitutional, and the parties further

stipulated that, "A reasonable time by which the State legis

lature shall have completed a valid Congressional Redistricting

Act [would be] February 29, 1972!" 344 F Supp at 212. The

legislature having failed to act by that date, or thereafter,

-10-

the Court considered various districting plans, and ordered

the Secretary of State to conduct an election pursuant to the

plan ordered by the Court. 344 F Supp at 217.

The Secretary of State has no more authority under

Michigan law to determine Congressional districts than the

Treasurer has to make appropriations. He does, however, have

the power to conduct elections, just as the Treasurer has the

power to issue warrants on the Treasury. The Court, quite

properly, and without a whimper of protest from the Attorney

General, ordered the Secretary of State to carry out his

function in such a fashion as to preserve the Constitutional

rights of Michigan citizens inspite of the fact that only the

legislature is empowered to create Congressional districts

under Michigan law. That is precisely what we ask here, and

in precisely the same fashion, even insofar as allowing the

legislature a reasonable time to act before the Court implements

its order. The only difference discernible in the exercise of

State powers by State officers between the two cases is that

there the Attorney General favored the substantive relief

requested and here he does not. The power of State officers

to act under order of the Court to prevent Constitutional

violations does not depend on whether the officers favor the

relief requested. •

-11-

B. It Has Been the_Lav; For The Last Sixty-

Four Years That Motions Such As That

Brought Here Are Not Barred By The

Eleventh Amendment. ■

The Attorney General, in citing Smith v Reeves, properly

states the rule of law that pertained to actions such as this in

1900 (In fact, that rule was established by In Re Avers,8 S.Ct.

164, 123 U.S. 443, 31 L. Ed. 216 (1887). However, in 1908, this

line of cases was reversed in Ex Parte Young ,209 U.S. 123, 28

S.Ct. 441, 52 L. Ed. 714. The rule has been followed ever since,

that State officials,acting in their official capacity,may be

sued to prevent Constitutional violations by them, the use of

the name of the State to effect a Constitutional wrong against

complainants not being a proceeding which affects the State in

its sovereign capacity. While the Eleventh Amendment does bar

direct money judgments against the State, it does not bar orders

requiring State officials to expend additional State Funds for

established State purposes if such funds are being spent in an

unconstitutional manner. Shapiro v. Thompson, 394, U.S. 618 (1969)

How firmly settled this principle of law is vividly illustrated

in the case of Rothstein v. Wyman, 41 USLW 2169 (CA 2, Sept.7,1972),

decided by the Second Circuit on September 7, 1972, and to the

knowledge of counself the latest significant case involving the

Eleventh Amendment. In that case, the Court, having previously

ordered the expenditure of State funds to rectify Constitutional

inequities in the Mew York State Welfare program, refused on

Eleventh Amendment grounds to provide retroactive payments. In

doing so, it noted that this was perhaps the minority view among

the Circuits, the majority permitting even such retroactive

payments by order of the Federal Courts. The Court mentioned

in passing that there was no longer any question that prospective

expenditures such as those at issue here could be required. There

is no need to belabor the point; this case simply does present

an Eleventh Amendment problem, any more than did Dunnell v

Austin, supra.

C. The July 7 Order Of This Court Is Still Vital.

State Defendants presume too much when they suggest that

the Stay of Desegregation Proceedings ordered by the Sixth Circuit

saps the vitality of this Order. Their presumption is that,

should this District Court be affirmed, no desegregation order

need be effected for the rest of the 1972 school year. Given

the clear command of Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of

Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971) that a finding of such a viola

tion as has been found here requires desegregation now, which has

in a legion of.cases been interpreted to mean within a matter

of days, their casual assumption that we can all just forget

about school desegregation until next year is nothing more than

wishful thinking. To be sure, the Sixth Circuit might extend its

Stay, and to be sure, it might reverse. But there is no precedent

cited, and the Detroit Board believes none exists, for the curious

assertion that the District Court which has made a ruling should

act on the presumption that it is going to be reversed. Judge

Roth issued the July 7th Order for the primary purpose of pre

serving the status quo ante litem so as not to make even more

difficult the task of school desegregation. There is no event

-13

which has intervened which makes that purpose any less important.

D. There Is No Serious Question Of The Standing

Of The Detroit Board Of Education To Bring..

This Motion.

The Detroit Board of Education is itself a Defendant in

this cause, and is required to obey the order of this Court to

provide a full year school program. Apparently unlike the State

Defendants, it has a keen desire to insure that it is capable

of doing exactly that. It desires to avoid any contempt, and

further desires that it not be forced to plead impossibility to

a charge of contempt. While this is basis enough for its stand

ing to bring this motion (now concurred in by the original maker

of the Motion which resulted in the July 7 Order), the Board

must insist that it does have a legitimate interest in the preser

vation of the Constitutional rights of its students. It is

empowered by statute to do "anything whatever that may advance

the interests of education, the good government and prosperity

of the free schools in said city, and the welfare of the public

concerning same." M.S.A. 15.3192, M.C.L.A. 340.192) Attempting

to insure that it can keep its schools open, and that the Con

stitutional rights of its students will remain inviolate would

seem to fall well within that grant of authority.

In sum, there is very little room for State Defendants'

argument that there simply is not an agent of the State, within

the jurisdiction of this Court, who is empowered to take action

that will insure the preservation of Constitutional rights, and

obedience to the previous order of the Courts. The law is clear,

the Constitutional violation is upon us, and there is no deterrent

to the jurisdiction of the Court.

-14-

#

II

THE APPROPRIATE TIME FOR THIS COURT TO ACT IS NOW

The Attorney General argues for State Defendants with

some passion that the legislature should be allowed the oppor

tunity to act, that if we will all be patient they will come

through and the problem will go away. The difficulty with the

argument is that nothing in the order requested by the Detroit

Board will in any way harm the chance that this will happen,

atlndeed, it is the fondest desire of the Detroit Board that thisrircr

Court not have to implement its Order because the legislature

has acted to uphold the Constitution.

The Order requested here requires State Defendants to

do nothing now except plan for the/eventuality that the legis

lature will not act. The Detroit Board knows of no reason why

this activity would in any way interfere with the legislative

process, and no such reason is given by State Defendants. Quite

the contrary, the Detroit Board would submit that the certain

knowledge that this Court will provide for the funding of the

Detroit schools in a mandatory fashion if the legislature does

not act first should, if it has any effect, spur the legislature

to prompt action.

What the Detroit Board proposes is nothing more than

was done in Dunnell v. Austin: first an unequivocal statement

that this Court will act if the legislature does not, a require

ment that responsible parties come forward in timely fashion with

plans to preserve Constitutional rights in the absence of

-15-

#

legislative action, and hearings leading to the adoption of

such a plan in the event of legislative default.

This in no way conflicts with any legislative timetable,

and it is devoutly hoped that legislative deliberations will be

successful.

However, there is no reason, simply because all parties

hope the legislature will act, for the Court to assume with cer

tainty that they will, simply based on the predictions of the

Attorney General. The fact of the matter is that to date, they

have not. -

There is ample precedent for the course suggested here

by the Detroit Board. In effect, what is suggested is an Order

of the Court made to enforce and protect the previous Order of

the Court. The Court would then be staying its own mandate pend

ing the action of the legislature. Dunnell v. Austin, supra.,

Standard Oil v. Standard Oil, 239 F Supp 97 (ED Mo 1966);

Ely V Klahr, 403 US 108 (1971); Rodriguez v. San Antonio, 337

F Supp 280 (WD Tex 1971) prob juris noted, 32 L. Ed. 2nd 665

(1972). These latter two cases were cited in our initial brief

not because the Detroit Board views this as a school finance case,

as the Attorney General suggests, but for the procedure used in

those cases by which the Court stayed its mandate to allow state

legislatures a reasonable period of time in which to act. Clearly

this is not a school finance case based on arguments of educational

needs or of any other variety. The Detroit Board raises no

-16-

issues whatsoever here as to how the schools are funded, leaving

that question in the first instance to the legislature, and in

the second instance to the State Defendants. Our sole concern,

in this forum at this time, is that the schools be funded by

whatever Constitutional means the State may provide. Should

the legislature fail to act, then and only then the mandate of

the Court would have to be enforced.

The overriding practical reasons why this Order should

issue now and planning begin forthwith are found in a cursory

\examination of State Defendant's Brief. The hostility to any

requirement that the State fund the Detroit schools is abundantly

evident. Should such hostility exist in the legislature it does

not augur well for the ability of the legislative leadership to

keep their commitment to pass the needed legislation.

Furthermore, consistent with their "self-serving and

therefore self-limiting view of their powers", it is quite likely

that the plan State Defendants come forward with will require

substantial modification through objections from other- parties.

Judge Roth described their performance with regard to a previous

planning function. "Put bluntly, State Defendants in this hearing

deliberately chose not to assist the Court in choosing an appro

priate area for effective desegregation of the Detroit public

schools. Their resistance and abdiction of responsibility through

out has been consistent with the other failures to meet their

obliations noted in the Court's earlier rulings". June 14 Findings

of Fact pp 6-7. Such an attitude here will require time for

hearing on plans if they are filed.

Finally, should the State Defendants elect to advocate

one of the more elaborate remedies which adhere slavishly to

their interpretation of state statute, such as dissection of the

District, or the diversion of funds from other State agents,

the effectuation of such a remedy will itself require some little

time.

There is one additional reason for the immediate action

of the Court, one which does not relate to the attitude of State

Defendants. It relates to the deleterious effect on the educa

tional process of the inherent uncertainty created by the finan

cial crisis which now surrounds Detroit schools. It cannot help

but have an enervating effect on student and staff morale, and

therefore, on the education the children of the District receive,

simply not to know whether school will continue through the

normal calendar or whether there will be an abrupt and disruptive

termination in mid-March. The students of this District not

only need their Constitutional rights to education, they need

to know that those rights are secure so that they may be fully

enjoyed, and so that the maximum benefit from the educational

program the district offers can be attained. At this juncture

only this Court can provide that security.

. Finally, a fact of the matter is though the State claims

that there were numerous meetings concerning, the financial crisis

of the Detroit Board of Education, those meetings produced zero.

They were pleasant conversation. The Board, was told to go back

for more millage. We did in May, August and November of 1972.

The millage was defeated. We were asked to support Proposition

C on the November 7, 1972 ballot. We did. Our President and

-18-

Superintendent went on the air urging the passage of the propo

sition. The fact of the matter is that until the Detroit Board

of Education, through its attorneys, announced that it would seek

to enforce the July 7, 1972 Order in Court and the announcement

by the Board that it would close schools on December 21, 1972

for an eight-week period that the State Defendants began taking

some concrete action. The action of the administrative board came

only after the announcement of the litigation and closing. The

statement of the legislative leaders came after the legal litiga

tion and announcement of closing. We still only have promises

and conversation. School children are entitled to action. The

Order proposed by the Detroit Board of Education would give the

State Defendants the incentive that apparently they need in order

to act to protect the Constitutional rights of the children of '

Detroit.

C O N C L U S I O N

There is an old Kikuyu saying popularized by the current

President of Kenya which translates roughly as "When elephants

fight, the grass dies." As Plaintiffs, State Defendants,

Suburban Defendants and the Detroit Board thrash through the

weighty and ponderous issues which have been present throughout

this case, it is crucial that we not stomp too heavily on the

real subject of all this dispute, the tender young minds of the

school children of this city. What more tragic result is imagin

able than for this litigation, in which so many have striven so

hard to preserve and protect Constitutional rights to education

as each saw them, to culminate in a situation in which there

was no education at all. It cannot be allowed to happen. This

Court has the power to .prevent it, and it should exercise that

power, so that all will know that those most previous rights

are secure.

Respectfully submitted,

RILEY AND ROUMELL

George T. Roumdll, Jr.

Louis D.Beer

Jane Keller Souris

Russ E. Boltz

Attorneys for Defendant Board

of Education of the School

District of the City of Detroit

December 8, 1972.

-20-

CERTIFICATION

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing Supplemental

Brief of Defendants Board of Education of the School District of

the City of Detroit, in view of Changed Circumstances Since The

Filing of This Motion and in Response to Answer to Emergency

Motion of the Board of Education of the City of Detroit has been

served upon counsel of record by United States Mail, postage pre

paid, addressed as follows:

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

NATHANIEL R.; JONES

General Counsel, NAACP

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. WINTHER MC CROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CKACKKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL R. DIMOND

ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center for Lav; £ Education

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

02138

DAVID L. NORMAN . •

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

ROBERT J. LORD

8388 Dixie Highway

Fair Haven, Michigan 48023

RALPH GUY

United States Attorney

Federal Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

DOUGLAS H. WEST

ROBERT B. WEBSTER

3700 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 43226

WILLIAM M. SAXTON

1881 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

EUGENE KRASICKY

Assistant Attorney General "'

Lav; Building; .

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

THEODORE SACHS

1000 Farmer .

Detroit, Michigan 48226

ALEXANDER B. RITCHIE

1930 Buhl Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

BRUCE A. MILLER .

LUCILLE WATTS ■

2460 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

RICHARD P. CONDIT '

Long Lake Building

860 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

KENNETH B. MC CONNELL .

74 West Long Lake Road •

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

DONALD F. SUGERMAN . '

2460 First National Building

Detroit,Michigan 48226

THEODORE. W. SWIFT

900 American Bank & Trust Rldrr

Lansing, Michigan 48933 ’

FRED W. FREEMAN '

CHARLES F. CLIPPERT

1700 N. Woodward Avenue

F. O. Box 509

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 4S013

+

* *'

JOHN F. SHANTZ

222 Washington Square Building

Royal Oak, Michigan 48067

December 8, 1972 Repsectfully submitted,

RILEY AND RQUMELL

f S/•Russ E. Boltz

■ &

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

-2-