Order and Injunction; Memorandum Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 28, 1986

56 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Order and Injunction; Memorandum Opinion, 1986. e5eaef8a-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c49cdd93-0249-41d0-849a-26faed28e104/order-and-injunction-memorandum-opinion. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Copied!

k 3 | Ee

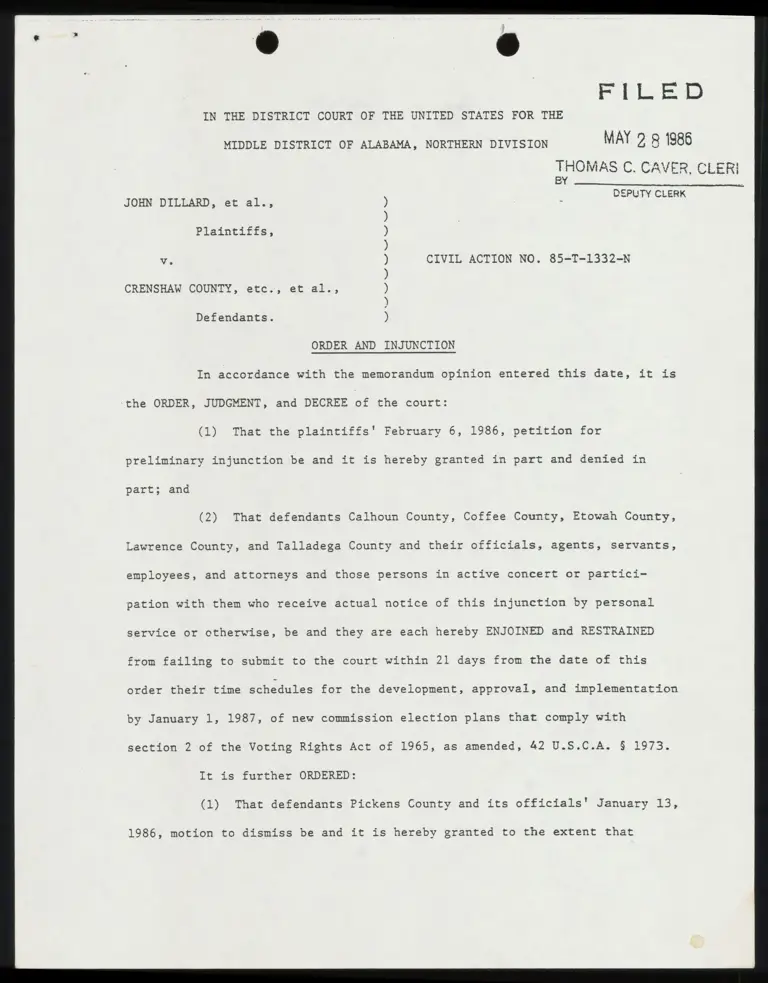

FILED

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION MAY 2 8 1886

THOMAS C. CAVER, CLER!

EY -

: DEPUTY CLERK

JOHN DILLARD, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

Vv. CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al.,

N

S

N

S

N

S

N

N

N

N

N

S

N

Defendants.

ORDER AND INJUNCTION

In accordance with the memorandum opinion entered this date, it is

the ORDER, JUDGMENT, and DECREE of the court:

(1) That the plaintiffs' February 6, 1986, petition for

preliminary injunction be and it is hereby granted in part and denied in

part; and

(2) That defendants Calhoun County, Coffee County, Etowah County,

Lawrence County, and Talladega County and their officials, agents, servants,

employees, and attorneys and those persons in active concert or partici-

pation with them who receive actual notice of this injunction by personal

service or otherwise, be and they are each hereby ENJOINED and RESTRAINED

from failing to submit to the court within 21 days from the date of this

order their time schedules for the development, approval, and implementation

by January 1, 1987, of new commission election plans that comply with

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 1973.

It is further ORDERED:

(1) That defendants Pickens County and its officials' January 13,

1986, motion to dismiss be and it is hereby granted to the extent that

plaintiffs' claim of intentional discrimination is barred by res judicata

and that the motion be and it is hereby denied in all other respects; and

(2) That the following motions be and they are hereby all denied:

defendants Calhoun County and its officials’ January 16, 1986, motion to

dismiss or to transfer; defendants Coffee County and its officials’ January

15, 1986, motion to dismiss; defendants Etowah County and its officials’

January 13, 1986, motion to dismiss and January 23, 1986, amended motion to

dismiss, motion to sever, and motion to transfer; defendants Lawrence County

and its officials’ January 10, 1986, motion to dismiss or transfer, or in

the alternative, to sever and rranelor, etc.; defendant Richard I. Proctor's

January 15, 1986, motion to dismiss; and defendants Talladega County and its

officials' January 23, 1986, motion to dismiss or to sever and transfer.

It is further ORDERED:

(1) That the plaintiffs' February 6, 1986, petition for class

certification be and it is hereby granted;

(2) That this action be and it is hereby declared properly

maintainable as a class action with respect to six plaintiff classes;

(3) That a class consisting of all black citizens of Calhoun

County, Alabama be and it is hereby certified as a plaintiff class, to be

represented by named plaintiffs Earwen Ferrell, Ralph Bradford, and Clarence

J. Jairrels;

(4) That a class consisting of all black citizens of Coffee

County, Alabama be and it is hereby certified as a plaintiff class, to be

represented by Damacus Crittenden, Jr., Rubin McKinnon, and William S.

Rogers;

(5) That a class consisting of all black citizens of Etowah

County, Alabama be and it is hereby certified as a plaintiff class, to be

represented by Nathan Carter, Spencer Thomas, and Wayne Rowe;

(6) That a class consisting of all black citizens of Lawrence

County, Alabama be and it is hereby certified as a plaintiff class, to be

represented by named plaintiffs Hoover White, Moses Jones, Jr., and Arthur

Turner;

(7) That a class consisting of all black citizens of Pickens

County, Alabama be and it is hereby certified as a plaintiff class, to be

represented by Maggie Bozeman, Jults Wilder, Bernard Jackson, and Willie

Davis; and

(8) That a class consisting of all black citizens of Talladega

County, Alabama be and it is hereby certified as a plaintiff class, to be

represented by Louis Hall, Jr., Ernest Easley, and Byrd Thomas.

It is further ORDERED:

(1) That this cause is set for trial on July 23, 1986, at 8:30

a.m. in the fourth floor courtroom of the federal courthouse in Montgomery,

Alabama;

(2) That the parties are to complete discovery and exchange lists

of witnesses and exhibits by July 16, 1986; and

(3) That this cause is set for pretrial on July 16, 1986, at 4:30

p.m. at the federal courthouse in Montgomery, Alabama.

DONE, this the 28th day of May, 1986.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT SE

* @

FILED

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION MAY 2 § 1986

lem av OMAS C. CAVER, CLER

— DEPUTY CLERK

JOHN DILLARD, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N Ve

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al.,

S

N

e

SN

N

N

N

N

N

N

S

N

S

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM OPINION

This lawsuit is a challenge to the at-large systems used to elect

county commissioners in nine Alabama counties with significant black

populations. The court understands that these counties are the last such

counties that still use at-large systems not already the subjects of federal

lawsuits.

The plaintiffs are a number of black citizens in the nine

counties, and the defendants are the nine counties and a number of their

officials. The plaintiffs have brought this lawsuit under section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 1973.} The court's

1. The plaintiffs also premise this lawsuit on the fourteenth and

fifteenth amendments to the U.S. Constitution by way of 42 U.S.C.A. § 1983.

However, since it appears that the reach of the section 2 claims in this

lawsuit equals or exceeds that of the claims based on the two comstitutional

amendments, the court does not reach the plaintiffs' constitutional claims

at this time. Prudent jurisdictional principles counsel that a court should

normally "not decide a constitutional question if there is some other ground

upon which to dispose of the case." Escambia County v. McMillan, 5.S.

s 5 104 S.Ct. 1577, 1579 (1984). See also Lee County Branch of NAACP

v. City of Opelika, 748 F.2d 1473, 1478 (11th Cir. 1984).

jurisdiction has been properly invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C.A. §§ 1331,

1343.

Since the filing of this lawsuit, the plaintiffs have entered into

settlements with three of the nine counties. ‘This lawsuit is now before the

court on several motions filed by the plaintiffs and the six remaining

counties and their officials. The significant issues raised by the motions

are whether the plaintiffs are entitled to preliminary injunctive relief;

whether the claims against three of the counties are barred by res judicata;

whether the claims against five of the counties should be severed and

transferred to another district; and whether plaintiff classes should be

certified.

For reasons that follow, the court concludes that preliminary

injunctive relief is warranted in part against five of the six counties;

that 2 clalm against one county is barred by res judicata; that the

remaining claims against all six counties should be tried im this district;

and that plaintiff classes should be certified.

I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND

The six counties remaining in this lawsuit are Calhoun County,

Coffee County, Etowah County, Lawrence County, Pickens County, and Talladega

Countyss They each have majority white populations and significant black

2. The three counties that settled are Crenshaw County, Escambia

County, and Lee County.

-li

populations, ranging from approximately 137 to 427.°

Five of the six counties are each governed by a board of

commissioners elected under at-large systems in both primary and general

elections. Not all at-large systems are alike, however, and the ones used

by the five counties have three structural features particularly relevant

here. The first feature is obvious. A candidate for commissioner must run

at-large, or county-wide, with all voters in the county allowed to vote for

the candidate. The second feature is that a candidate must run for a

numbered post or separate place. Each commissioner position carries a

separate number, and each candidate qualifies for a specific number and

place, with each voter allowed to vote for only one candidate in each place.

The third feature is that a candidate must receive a majority of votes cast

in the primary to win the nomination of a political party. If no candidate

receives a majority of votes, a run-off primary election is held. The

majority vote requirement does not apply to general elections.

The sixth county, Pickens County, is also govermed by a board of

commissioners, but the commissioners are elected under az "dual system."

3. According to the 1980 census, the black population of each

county is as follows:

Percent Black

County Total Population Black Population Population

Calhoun 119,761 21,074 17.607

Coffee 38,533 5,532 16.957

Etowah 103,057 13,809 13.407

Lawrence 30,170 5,074 16.827

Pickens 21,481 8,978 41.807

Talladega 73,826 22.745 30.817

Primary elections are held from four "single-member" districts, with the

voters in each district restricted to voting only for candidates for the

commissioner representing that district; whereas, general elections are

conducted at-large in the same manner the other five counties conduct their

general elections for commissioners.

The six counties have a clear history of racially polarized

elections for both state and county officials, and no black person has ever

been elected commissioner under the at-large systems used by the counties.

7. LEGAL BACKGROUND

It is now generally undisputed that, where there is a history of

elections polarized along racial or other group lines, at-large systems

containing features similar to three described above tead "to minimize the

voting strength of minority groups by permitting the political majority to

elect all representatives of the district." Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613,

616, 102 S.Ct. 3272, 3275 (1982) (emphasis in original). By contrast, a

minority might be able to elect one or more representatives, even in an

at-large system, if the election is by a plurality without numbered places.

For example, a black candidate could have a fair opportunity to be elected

by a plurality of the vote if the black voters concentrate their vote behind

one candidate or a limited number of candidates, while the white voters

divide theirs among a number of candidates. City of Rome v. United States,

446 U.S. 156, 183-84 & n. 19, 100 S.Ct. 1548, 1565 & nw. 19 (1980). See slsc

Rogers, 458 U.S. at 627, 102 S. Ct. at 3280 ("the requirement that

candidates run for specific seats...enhances [black voters'] lack of access

di

[to the political system] because it prevents a cohesive group from

concentrating on a single candidate"); H.R. Rep. Fo. 227, 97th Cong., 1st

Sess. 18 ("discriminatory elements of the elections process ... [include]

numbered posts....") Similarly, a minority might be able to elect ome or

more representatives if, first, the political unit were divided into

single-member districts, with the voters in each district restricted to

voting only for candidates for the commissioner representing that district;

and, second, one or more districts had a sufficient number of black voters

to elect a black candidate. Rogers, 458 U.S. at 616, 102 s.Ct. at 3275.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court has held that, even though such

at-large systems have a "winner-take-all" aspect and a "tendency to submerge

minorities and to overrepresent the winning party," Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403

U.S. 124, 158-139, 91 S.Ct. 1858, 1877, (1971), they are not illegal per se.

Rogers, 458 U.S. at 616-17, 102 S.Ct. at 3275.

The plaintiffs claim that the at-large election systems used in

the six counties violate section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 1973. A violation of section 2 as recently amended

in 1982 is established if official action was taken or maintained with a

racially discriminatory "intent" or the action has racially discriminatory

"results," determined according to certain Congressionally approved

enttarie.’ McMillan v. Escambia County (Escambia II), 748 F.2d 1037, 1046

4. In order to make out a results claim under section 2, the

plaintiffs must show that "as a result of the challenged practice or

structure plaintiffs do not have an equal opportunity to participate in the

political processes and to elect candidates of their choice.” S. Rep. No.

417, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. 28, reprinted in 1982 U.S. (footnote 4 continues)

on,

(5th Cir. 1984) (Former Fifth); Buskey v. Oliver, 565 F. Supp. 1473, 1481 &

n. 18 (M.D. Ala. 1983). In this case, the plaintiffs contend both that the

(footnote 4 continued) Code Cong. & Ad. News 177, 206. Factors typically

considered in evaluating such a claim are:

1. the extent of any history of official

discrimination in the state or political sub-

division that touched the right of the members

of the minority group to register, to vote, or

otherwise to participate in the democratic

process;

2. the extent to which voting in the

elections of the state or political subdivision

is racially polarized;

3. the extent to which the state or

political subdivision has used unusually large

election districts, majority vote requirements,

anti-single shot provisions, or other voting

practices or procedures that may enhance the

opportunity for discrimination against the

minority group;

4. if there is a candidate slating process,

whether the members of the minority group have

been denied access to that process;

5. the extent to which members of the

minority group in the state or political sub-

division bear the effects of discrimination in

such areas as education, employment and health,

which hinder their ability to participate

effectively in the political process;

6. whether political campaigns have been

characterized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the

minority group have been elected to public

office in the jurisdiction.

(footnote 4 continues)

at-large systems used by the six counties were created with a racially

discriminatory intent and that the systems have racially discriminatory

results. They have, however, informed the counties and the court that they

intend to pursue their intent claims first and that they will pursue a

results claim against a county only if their intent claim against the county

fails.

III. PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

The plaintiffs request preliminary injunctive relief against

continued use of at-large systems in the six counties. Adhering to their

announced trial strategy, they limit the premise of their request to their

section 2 intent claims.

footnote 4 continued)

Additional factors that in some cases have had

probative value as part of plaintiffs’ evidence

to establish a violation are:

[8] whether there is a significant lack of

responsiveness on the part of elected officials

to the particularized needs of the members of

the minority group.

[9] whether the policy underlying the

state or political subdivision's use of such

voting qualification, prerequisite to voting,

or standard, practice or procedure is tenuous.

Id. at 28-29, 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News at 206-207. There is no

requirement that any particular one of these factors or number of these

factors be proved; rather, the court's concern should be the "totality of

the circumstances." Id. at 207 & n. 118. See also White v. Regester, &12

U.S. 755, 93 $.Ct. 2332 (1973); Zimmer v., McEeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973) (en banc), aff'd on other grounds sub nom. East Carroll Parish Sch.

Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636, 96 5.Ct. 1083 (1976).

hy

To obtain a preliminary injunction, the plaintiffs must show that

"(1) there is a substantial likelihood that they will prevail on the merits

at trial; (2) they will suffer irreparable harm if they are or granted the

injunctive relief; (3) the benefits the injunction will provide them

outweigh the harm it will cause the [defendants]; and (4) the issuance of

the injunction will not harm public interests.” Callaway v. Block, 763 F.24

1283, 1287 (llth Cir. 1985). The plaintiffs have met these requirements as

to all defendant counties except Pickens County. Pickens County's

affirmative defense of res judicata precludes preliminary relief, as the

court explains in part IV of this opinion.

A. Likelihood of Success

There are, at least, two methods of establishing a section

”y 2 intent claim. The plaintiffs have shown a substantial likelihood of

success under both methods.

i.

One method by which a plaintiff may establish a prima facie case

of discriminatory intent under section 2 is by showing, first, that racial

discrimination was a "substantial" or "motivating" factor behind the

enactment or maintenance of the electoral system and, second, that the

: : ; 3

system continues today to have some adverse racial impact. Hunter v.

5. The discriminatory results needed to establish a section 2

violation in the absence of intentional discrimination should not be

confused with the present day adverse racial impact needed to establish a

section 2 intent claim. The former is more a term of art, established

according to certain Congressionally approved criteria described in footnote

4, supra; whereas, the latter is less stringent and may be met by any

evidence that the challenged action is having significant adverse impact on

black persons today. See Note, The Constitutional Significance of the

Discriminatory Effects of Ar-large Elections, 91 Yale L.J. 974 (1982),

—E-

Underwood, U.S. . , 105 S.Ct. 1916, 1920, 1923 (1985) (Alabama

constitutional provision disenfranchising persons convicted of crimes cf

moral turpitude was enacted for racially discriminatory purpose and

continues to have adverse racial impact in violation of the fourteenth

amendment); Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development

Corporation, 429 U.S. 252, 264-66, 97 S.Ct. 553, 363 (1977) (city did not

deny rezoning for reasons of race in violation of the fourteenth amendment);

NAACP v. Gadsden County School Board, 691 F.2d 978, 981 (llth Cir. 1982)

(at-large election system for school board members was adopted for racially

discriminatory purpose and continues to have adverse racial impact in

violation of the fourteenth amendment). See also Note, The Constitutional

Significance of the Discriminatory Effects of At-large Elections, 91 Yale

L.J. 974, 976-77 (1982). If the plaintiff establishes these two elements,

the burden then shifts to the scheme's defenders to demonstrate that the

scheme would have been enacted without the purposefully discriminatory

factor. Hunter, U.S. at , 105 8.Ct, at 1520. See also Mt, Healthy

City School District v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274, 287, 97 S.Ct. 568, 576 (1977).

Of course, in proving discriminatory intent under section 2 a

plaintiff is not restricted to direct evidence, Rogers, 458 U.S. at 818, 102

S.Ct. at 3276; rather, "determining the existence of a discriminatory

purpose 'demands a sensitive inquiry into such circumstantial and direct

evidence of intent as may be available.'" 1Id., quoting Arlington Heights,

429 0.5, at 266, 97 8.Ct. at 564,

Furthermore, that the plaintiffs in this section 2 claim have

placed on this court the task of looking behind legislative action is not an

Kar

impediment. Admittedly, democratic principles teach that courts should

ordinarily defer to decisions of legislative or administrative bodies about

governmental goals and the means for achieving those goals. However, race

discrimination is a forbidden consideration whose presence in the

legislative or administrative process taints the process. The usual

judicial deference thus does not obtain where a plaintiff charges in a

section 2 claim that invidious race discrimination was a substantial or

motivating consideration in the legislative or administrative process. As

the Supreme Court explained in Arlington Heights, "racial discrimination is

not just another competing consideration. Where there is proof that a

discriminatory purpose has been a motivating factor in the [legislative or

administrative] decision, this judicial deference is no longer justified."

429 0.8. at 265-66, 97 S.Ct, at 563.

For these same reasons, a plaintiff asserting a section 2 intent

claim need not meet a more exacting standard of proof merely because

legislative or administrative action is challenged. As the Supreme the

Court observed in Arlington Heights, the law "does not mTequire a plaintiff

to prove that the challenged [legislative or administrative] action rested

solely on racially discriminatory purposes," or even that such purposes were

"dominant" or "primary." 429 U.S. at 265, 97 S.Ct. at 563. The plaintiff

need establish only that the forbidden consideration of race discrimination

was a substantial or motivating factor before the burdem of salvaging the

challenged legislative or administrative action shifts to the defenders of

the action. Id.; Hunter, supra. As the Court observed, "[l]egislation is

frequently multipurposed: the removal of even a 'subordinate' purpose may

-10-

shift altogether the consensus of legislative judgment supporting the

statute." Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 265 n. 11, 97 $.0t. at 563 n. 11,

quoting McGinnis v. Royster, 410 U.S. 263, 276-77, 93 S.Ct. 1055, 1063

£1973).

Admittedly, the court has cited and relied upon such fourteenth

amendment cases as Hunter, Rogers, Arlington Heights, and NAACP in describ-

ing how a plaintiff may establish a section 2 intent claim. However, the

legislative history of the 1982 amendments to section 2 clearly indicates

that the 1982 amendments derive from the fourteenth amendment as well as the

fifteenth amendment. S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong. 2d. Sess. 39, reprinted in

1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 177, 217; H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., lst

Sess. 31. Accordingly, it is appropriate that the manner for establishing a

section 2 intent claim should be along the same lines as that for

establishing intent under the fourteenth amendment. See Escambia II, 748

F.2d at 1046 ("this court already has determined that the at-large election

system was maintained for a discriminatory purpose and thus violated the

fourteenth amendment. ... This showing of intent is sufficient to

constitute a violation of section 2").

With the preceding principles in mind, the court is firmly

convinced that the plaintiffs have more than adequately shouldered the first

requirement for a preliminary injunction against Calhoun County, Coffee

County, Etowah County, Lawrence County, and Talladega County; the plaintiffs

have shown a clear and substantial likelihood of prevailing on their section

2 intent claims. First, the court is convinced that in the 1960's the State

of Alabama enacted numbered place laws with the specific intent of making

local at-large systems, including those used in county commission elections,

lie

more effective and efficient tools for keeping black voters from electing

black candidates. Second, the court is convinced that the at-large systems,

as modified in the 1960's and used today by the five counties, are still

having their intended racist impact. The court is also convinced that the

five counties have failed to meet their burden of showing that the numbered

place laws would have been enacted without the discriminatory purpose. The

evidentiary basis for these conclusions is as follows.

The testimony and opinions of a well-respected historian, Dr.

Peyton McCrary, established that in the 1960's, to meet the growing threat

of black voters and possible black office holders, the Alabama legislature

refashioned the at-large electoral systems then in use in many counties and

cities throughout the state. The discriminatory centerpiece of the new

at-large systems was the numbered place laws.

According to the historian, the state was openly and unabashedly

intent on finding new strategies to keep black persons out of the electoral

process in the wake of the Supreme Court's 1944 ban of all-white primaries

in Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649, 64 S.Ct. 757 (1944). Since the winner

of a Democratic primary in Alabama was virtually guaranteed a victory in the

general election, the all-white primary had been an effective state-wide

method of denying black persons a meaningful opportunity to participate in

the election process.

In response to the judicial ban on all-white primaries, the

Alabama legislature passed a bill in the 1950's outlawing single-shot voting

in municipal elections conducted at-large. Single-shot voting generally

"enables a minority group to win some at-large seats if it concentrates its

vote behind a limited number of candidates and if the vote of the majority

is divided among a number of candidates.! City of Rome, 446 U.S. at 184 n.

id.

rm | EAN hI ACR Fond or 3B Ne Se ENR) 82 TE ARTA Ent 3 a en ah A © BS a ANAS We AAAS

19, 100 S.Ct. at 1565 n. 19, quorinz U.S, Commigsion on Civil Righes, "The

Voting Rights Act: Ten Years After," pp. 206-07 (1975). Single-shot voting

has been described as follows:

Consider [a] town of 600 whites and 400

blacks with an at-large election to choose

four council members. Each voter is able to

cast four votes. Suppose there are eight

white candidates, with the votes of the

whites split among them approximately

equally, and one black candidate, with all

the blacks voting for him and no one else.

The result is that each white candidate

receives about 300 votes and the black

candidate receives 400 votes. The black has

probably won a seat. This technique is

called single-shot voting.

City of Rome v. United States, supra. A law banning simgle—shot voting

generally requires that each elector cast votes for as many candidates as

there are positions. See, e.g., Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209, 217 n. 10

(5th Cir. 1978), cert. denied, 446 U.S. 951, 100 S.Ct. 2916 (1980). Such =

law seriously disadvantages minority voters "because it may force them to

vote for nonminority candidates, thus depreciating the relative position of

minority candidates." Id.

State Representative Sam Englehart of Macon County, Alabama was

the sponsor of the state laws banning single-shot votimg. Englehart was the

founder of the racist White Citizens Council Movement of the 1950's and was

a notorious segregationist. Englehart was also the author of the infamous,

racially inspired Tuskegee gerrymander struck down by the federal courts in

the 1960's. See Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 81 S.Ct. 125 (1960)

(holding that a constitutional challenge to the Tuskegee gerrymander could

be entertained by the federal courts.) The racial purpose behind the laws

135"

banning single-shot voting was not kept secret. Englehart's father-in-law,

then a state senator, explained to a newspaper that the legislature had

passed the laws because "there are some who fear that the colored voters

might be able to elect one of their own race to the [Tuskegee] city council

by 'single shot' voting." For the same racial reasons, the ban on single-

shot voting was extended in the late 1950's to cover at-large primary

elections for county commissioners.

The laws banning single-shot voting were repealed in 1961 and

replaced with laws requiring that candidates run for numbered places in all

state, county and municipal at-large elections, both primary and general.

The numbered place laws had the same effect on black voting strength in

at-large elections as the laws banning single-shot voting, and there can be

no doubt that that they sprang from the same motivation. Shortly after the

enactment of numbered place laws, at a meeting of the State Democratic

Executive Committee with Englehart presiding, a committee member explained

the state legislature's open and unabashed racist motive behind the new

numbered place laws and the significant role the laws were to play in

keeping black voters from electing black persons in the primary elections to

be conducted by the Committee:

[W]e have got a situation in Alabama that we are

becoming more painfully aware of every passing day,

that we have a concerted desire and a campaign to

register Negroes en masse, regardless of the fact

that many of them ordinarily cannot qualify because

of their criminal records, or criminal attitudes,

because of the fact that they are illiterate and

cannot understand or pass literacy tests.... [I]t

has occurred to a great many people, including the

legislature of Alabama, that to protect the white

lt

people of Alabama, that there should be numbered

place laws."

These racially inspired numbered place laws exist and operate today.

Therefore, regardless of the reasons for which the at-large

systems were put into place in various counties, including the five counties

sued here, the numbered place laws have inevitably tainted these systems

wherever they exist in the state. In adopting the laws, the state reshaped

at-large systems into more secure mechanisms for discrimination. And as

the evidence makes clear, this reshaping of the systems was completely

intentional.

This evidence adequately supports the conclusion that the at-large

systems now being used in the five counties are a product of intentional

discrimination. Nevertheless, any remaining doubt that the systems were

racially inspired is dispelled by further evidence that the systems were

created in the midst of the state's unrelenting historical agenda, spanning

from the late 1800's to the 1980's, to keep its black citizens economically,

socially, and politically downtrodden, from the cradle to the grave. See

Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 267, 97 S.Ct, at 364 ("the historical

background of the [challenged] decision is one evidentiary source,

particularly if it reveals a series of official actions taken for invidious

purposes"); Ammons v. Dade City, 783 F.2d 982, 988 (llth Cir. 1986) ("a

large body of constitutional jurisprudence ... recognizes that the

historical context of a challenged activity may constitute relevant evidence

of intentional discrimination").

The plaintiffs have presented considerable evidence demonstrating

that the state has an extensive history of discriminating against black

= } 5

persons in the area of voting rights and specifically by using at-large

systems. The plaintiffs’ historical presentation began with evidence dating

from Alabama's so-called 'redemption' by the white-supremacist Democratic

party around 1870. In the late 1860's, the Republicans temporarily gained

control in Alabama and were able both to author a new constitution that

provided for universal suffrage and to have a significant voice in the state

legislature. In 1870, however, the Democratic party, which openly and

vigorously promoted white supremacy, won the governorship and control of the

house, and, in 1874, the Democrats regained complete control of the state

government.

Following this '"redemption' by the white-supremacist Democratic

party, the state legislature passed a series of local laws that eliminated

elections for county commission and instead gave the governor the power to

appoint the commissioners. This system of gubernatorial appointment was

particularly favored in black belt counties threatened with black voting

majorities. According to the plaintiffs’ historian, the gubernatorial

appointment system is widely understood to have been designed to prevent the

election of black county commissioners.

The rise of the Populist movement in the 1890's triggered new

changes in Alabama's election laws. Since the Populist movement had

considerable support among black persons and poor white persons, steps had

to be taken to prevent these two groups from joining together in potentially

powerful coalitions. In 1893, the legislature passed a complex election

statute known as the Sayre Law, "[t]he express purpose of [which], according

to its author, was to legally eliminate the Negro from politics in Alabama."

-lf=

Bolden v. City of Mobile, 542 F. Supp. 1050, 1062 (S.D. Ala. 1982). The

Sayre Law apparently had its desired effect, for black voter turnout dropped

by 22% from 1892 to 1894 and thereafter remained below 50%. Id. at 1062.

The Populist movement not only inspired the Sayre Law, it also set off the

first of several shifts between single-member district and at-large

elections for county commissioners. The plaintiffs' historian testified

that because at-large elections have the effect of diluting the black vote,

they are particularly favored when black persons' right to vote is

relatively unfettered and black voters stand a chance of electing a

candidate of their choice; when black persons' access to the ballot box is

circumscribed, on the other hand, single-member districts gain in

popularity. In 1894, when the Populist movement had just reached its peak

and black persons were still able to vote fairly freely, numerous counties

moved from single-member districts to at-large elections, apparently in

order to undermine possible coalitions between black persons and poor white

persons.

This trend toward at-large elections reversed itself after the

1901 Constitutional Convention. There can be little question but that a

major purpose of the 1901 Convention was to disenfranchise black persons.

As the Supreme Court recently commented in another case, expert testimony

"showed that the Alabama Constitutional Convention of 1901 was part of a

movement that swept the post-Reconstruction South to disenfranchise blacks.

.. The delegates to the all-white convention were not secretive about their

purpose.’ Hunter v. Underwood, B.S. A y 305 S.Ct. 1916, 1920-21

(1985). The 1901 Constitution contained so many different voter

-17-

qualifications that by 1909 all but approximately 4,000 of the nearly

182,000 black persons of voting age in Alabama had been removed from the

rolls of eligible voters. Bolden, 542 F. Supp. at 1063 & n. 10. After the

1901 Convention, counties increasingly moved toward single-member districts;

since most black persons could no longer vote, the use of single-member

districts was obviously fairly "safe." In fact, the legislature was so

confident that black persons had been removed as a political force that in

1907 it passed a law providing for single-member district elections of

aldermen in all cities in the state. Id. at 1063.

A final shift back towards at-large elections began in 1944.

According to the plaintiffs’ historian, in response to both the Supreme

Court's ban of all-white primaries and the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1964,

and 1965, many counties shifted back to at-large elections. This shift was

in substantial measure parallel with the legislature's racially inspired

decisions to refashion at-large systems to prohibit single-shot voting and

later to require numbered places.

Again, state legislators were often open and unashamed of their

intent. For example, State Senator Clark, who introduced a bill in 1965 to

shift elections in Barbour County, Alabama from single-member districts to

an at-large system, explained to a local newspaper that Ma further

consideration in introducing this bill would be to lessen the impact of any

bloc vote in any district which has a relatively small number of eligible

voters"; the term "bloc vote" was commonly used at that time as a code to

refer to the black vote. According to another local newspaper, supporters

18

of a similar bill for Choctaw County, Alabama "advocate the change because

of the increasing number of Negro voters that have been qualified in recent

weeks.... They maintain that by electing the [county] commissioners on an

at-large basis the threat of an effective Negro bloc vote will be

eliminated, ? Since black voters once again posed a threat to total control

of the electoral process by white persons, single-member districts were

abandoned and at-large systems were put into place.

In addition to implementing and maintaining at-large elections,

reinforced by laws banning single-shot voting and laws requiring numbered

places, the state passed a number of other statutes designed to discriminate

against black voters. For example, starting shortly after the all-white

primaries were struck down, the state passed a series of laws requiring

black persons who wished to register to vote to satisfy different and more

stringent standards and tests than white persons. See, e.g., United States

v. Parker, 236 F. Supp. 511 (M.D. Ala. 1964); United States v. Penton, 212

F. Supp. 193 (M.D. Ala. 1962); Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D.

Ala.), aff'd 336 U.S. 933, 69 S.Ct. 749 (1949). Other barriers placed in

the way of black voters after 1944 include racial gerrymandering, Sims v.

Baggett, 247 F. Supp. 96 (M.D. Ala. 1965), discriminatory administration of

the poll tax, United States v. Alabama, 252 F. Supp. 95 (M.D. Ala. 1966),

and appointment of disproportionately few black poll officials. Harris v.

Graddick (Harris II), 601 F. Supp. 70 (1984); Harris v. Graddick (Harris I),

6. Although the Choctaw County voters defeated the proposed

change in a local referendum for reasons unrelated to race, this evidence

makes clear that there was widespread understanding that at-large elections

have an adverse impact on the black vote.

—10-

593 PF. Supp. 128 (M.D. Ala. 1984).

These efforts to keep black persons from voting and being elected

to office paralleled and complemented the state's efforts to discriminate

against black persons in all other areas of their lives. As children, black:

persons were required to go to segregated schools, see, e.g., Lee v. Macon

County Bd. of Ed., 231 F. Supp. 743 (M.D. Ala. 1964) (three-judge court),

play in segregated parks, Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 176 F. Supp. 776

(M.D. Ala. 1959), modified, 277 F.2d 364 (5th Cir. 1960), and use segregated

recreational facilities. Smith v. Y.M.C.A., 316 F. Supp. 899 (M.D. Ala.

1970), aff'd as modified, 462 F.2d 634 (5th Cir. 1972), As they grew up,

black persons faced continued discrimination in education, United States v.

Alabama, 628 F. Supp. 1137 (N.D. Ala. 1985), and were also discriminated

against in state employment, see, e.g., Paradise v. Prescott, 585 F. Supp.

72 (M.D, Ala 1383), aff'd, 767 F, 24 1514 (ilth Cir. 19835) {racial

discrimination in promotion of state troopers); NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp.

703 (M.D. Ala. 1972), aff'd, 493 F. 24 614 (5th Cir, 1974) (ragial

discrimination in hiring of state troopers); United States v. Frazier, 317

F. Supp. 1079 (M.D. Ala. 1970) (four departments of Alabama state government

with a total of approximately 3,000 employees engaged in pattern or practice

of employment discrimination against blacks); Marable v. Alabama Mental

Health Board, 297 F. Supp. 291 (M.D. Ala. 1969) (three-judge court) (state

mental health board discriminated against black employees), cultural

opportunities, Cobb v. Montgomery Library Board, 207 F. Supp. 880 (M.D. Ala.

1962) (blacks excluded from public library and museum), and even their

private lives. United States v. Britain, 319 F. Supp. 1058 (N.D. Ala. 1970)

(miscegenation laws).

Furthermore, no matter what form of putlic transportation they

chose, black persons were subjected to segregation. See, e.g., United

States v. City of Montgomery, 201 F. Supp. 590 (M.D. Ala. 1962)

(state-imposed segregation in municipal airport facilities); Lewis v.

Greyhound Corp., 199 F. Supp. 210 (M.D. Ala. 1961) (state policy of

maintaining segregated bus terminals); Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707

(M.D. Ala.) (three-judge court), aff'd mem., 352 U.S. 903, 77 S. Ct. 145

(1956) (segregated city buses required by state statute and city ordinance).

Black mental patients were placed in segregated and inferior public

hospitals, Marable, 297 F. Supp. at 294, and black persons were

discriminated against on both sides of the legal system; they were routinely

excluded from juries, see, e.g., Black v. Curb, 464 F.2d 165 (5th Cir.

1972), and they were kept in segregated quarters in the state's jails and

prisons. Washington v. Lee, 263 F. Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala. 1966) (three-judge

court), aff'd, 390 U.S. 333, 38 8.Ct., 994 (1967).

As the late Judge Richard T. Rives stated, "from the

Constitutional Convention of 1901 to the present, the State of Alabama has

consistently devoted its official resources to maintaining white supremacy

1

and a segregated society." United States v. Alabama, 252 F. Supp. 95, 101

(M.D. Ala. 1966) (three-judge court).

On this extensive historical record based on both direct and

circumstantial evidence, the conclusion is inescapable that in the 1960's

the state superimposed numbered place requirements on all at-large systems

with the specific intent of discriminating against black persons.

=3tl

The state's adoption of numbered place laws as a means of discrimination was

also entirely consistent with its longstanding history of discrimination.

From the late 1800's through the present, the state has consistently erected

barriers to keep black persons from full and equal participation in the

social, economic, and political life of the state.

The plaintiffs have therefore established a substantial likelihood

of prevailing on their section 2 intent claims against Calhoun County,

Coffee County, Etowah County, Lawrence County, and Talladega County. The

plaintiffs have met all requirements for such claims. First, in the 1960's,

the State of Alabama passed sunberad place laws with the specific intent of

making at-large election systems more effective and efficient instruments

for keeping black voters from electing black candidates. Second, these

systems, as redesigned, are still having their intended racist impact. In

the racially polarized political atmosphere of the five counties, black

voters are still unable to elect black candidates to commission seats

because of the systems. And third, the five counties have failed to show

that the numbered place laws would have been enacted in the absence of the

discriminatory intent behind them.

ii.

As the court stated earlier, there are, at least, two methods of

establishing a claim of intentional discrimination under section 2. The

- 0

second method is based primarily on the evidentiary concept of pattern and

practice.

Again borrowing from fourteenth amendment law and other, similar

law, a plaintiff may establish a prima facie case of intentional

discrimination by showing, first, that those responsible for the enactment

or maintenance of the challenged electoral scheme have engaged in a pattern

and practice of enacting and maintaining other, similar schemes for racially

discriminatory reasons; and, second, that the challenged scheme has some

present day adverse racial impact. The plaintiff need mot show that race

discrimination was the sole reason for these other schemes; rather, the

plaintiff need show only that race discrimination was a substantial or

motivating factor behind these schemes. If the plaintiff establishes both

these elements, the burden then shifts to the defenders of the challenged

scheme to show either that the scheme was not a product of race

discrimination or that, if it was, it would have been emacted or maintained

even in the absence of the discriminatory purpose. See Xeyes vw. School

District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 208, 93 S.Ct. 2686, 2697 (1973) (where

plaintiffs show that school authorities have effectuated an intentionally

segregative policy in a meaningful portion of the school system, the court

may infer that similar impermissible considerations have motivated their

actions in other areas of the school system, and burden shifts to the school

authorities to show otherwise as to other areas); see also International

Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 362, 97 S.Ct. 1843,

=D Fu

1868 (1977) (where plaintiffs prove that employer engaged in a pattern and

practice of discrimination in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. §§ 2000e through 2000e-17, burden then

shifts to employer to show that individual applicant was denied employment

for lawful reason); Lee v. Washington County Board of Education, 625 F. 2d

1235, 1239 (5th Cir. 1980) (once purposeful discrimination in hiring is

proved against class in an employment discrimination action under 42

U.S.C.A. §§ 1981, 1983, burden then shifts to the employer to show that the

individual members of class seeking relief would not have been hired absent

the discrimination).

The plaintiffs have shown a substantial likelihood of prevailing

on this second method of establishing a section 2 intent claim, for they

have established a prima facie case of race discrimination which the

defendants have not rebutted. First, the preceding evidence shows that the

Alabama legislature, which was responsible for the at-large systems in the

five counties, has consistently enacted at-large systems for local

governments during periods when there was a substantial threat of black

participation in the political process. This evidence, set against the

7. The plaintiffs contend that a plaintiff should not have the

burden of establishing present day adverse racial impact, but rather that

once the plaintiff establishes a pattern and practice of race discrimi-

nation the defenders of the challenged action should have the burden of

establishing no present day adverse impact. The court disagrees. See

International Brotherhood of Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 362, 97 S.Ct. at 1868

(to shift burden to employer with respect to individual employees entitled

to relief, plaintiffs in Title VII pattern and practice suit must "show that

the alleged individual discriminatee unsuccessfully applied for a job");

Keves, 413 U.S. at 208, 93 S.Ct. at 2697 (presumption of discriminatory

intent based on evidence of segregative intent in one portiom of a school

system is created only with respect to "other segregated schools within the

system).

-24-

background of the state's unrelenting and undisputed history of race

discrimination, convinces the court that the enactment of the at-large

systems during such periods was not adventitious but rather racially

inspired. The evidence therefore reflects that the legislature has engaged

in a pattern and practice of using at-large systems as an instrument for

race discrimination. Second, as already stated, the evidence shows that the

at-large systems used by the five counties to elect commissioners have a

present day adverse racial impact. The counties have not at this time

satisfactorily met their burden of refuting this prima facie case. The

counties have not shown that thelr at-large systems were not a product of

race discrimination, nor have they shown that their systems would have been

enacted in the absence of race discrimination.

iid.

In light of these conclusions, the next issue the court must

consider is what preliminary injunctive relief would be appropriate against

the five counties. Four of the five counties are to elect one or more

county commissioners this year. The primary elections are scheduled for

June 3, 1986, with runoff elections, if necessary, scheduled for June 24;

and the general elections are to be held in November. The plaintiffs seek a

preliminary injunction requiring the counties to implement single-member

districts immediately and to postpone any primary and general elections for

county commissioners until such time as the plans are implemented. In

addition, the plaintiffs seek to shorten the terms of incumbents who are

«25

now scheduled to remain in office past the end of this year, and they seek

to require Coffee County, the one county that does not have commission

elections this year, to hold elections at the same time as the other four

counties. :

For several reasons, the court refuses to order the five counties

to implement new election plans, including possibly single-member district

plans, until after this lawsuit has been finally heard on the merits.

First, while it is clear that the existing at-large systems are infirm, it

is inappropriate at this time to order a single remedy for all of the

counties. The court simply does not have sufficient evidence about the

individual characteristics of each county. Second, even if it were clear

that all of the counties should be required to adopt simgle-member

districts, it would be unfair and infeasible to require them to do so by

June. The plaintiffs did not even seek preliminary injunctive relief until

February 1986 and were unable to produce all of the evidence necessary to

consider the motion until late March, less than three months before the

primaries are scheduled to begin. Finally, given that the plaintiffs’

requested injunction goes well beyond merely preserving the status quo while

the litigation is pending, the very nature of their request demands that the

court proceed with caution. See, e.g., Martin v. International Olympic

Committee, 740 F.2d 670, 675 (9th Cir. 1984) ("[i]ln cases ... in which a

party seeks mandatory preliminary relief that goes well beyond maintaining

the status quo pendente lite, courts should be extremely cautious about

issuing a preliminary injunction"); Harris v. Wilters, 596 F.2d 678, 680

(5th Cir. 1979) ("[olnly in rare instances is the issuance of a mandatory

-26-

preliminary injunction proper"); Jordan v. Wolke, 593 F.2d 772, 774 (7th

Cir. 1978) ("mandatory preliminary writs are ordinarily cautiously viewed

and sparingly issued"). :

While the court refuses to order the counties to implement new

election plans in time for the June elections, the court does recognize that

with each election the at-large systems impermissibly dilute the vote of

thousands of black citizens and thus must be eliminated as soon as possible.

The court will therefore set a trial date for mid-summer of this year and

will enter a preliminary injunction requiring that, pending trial, each

county must submit a time schedule for developing a new election plan,

obtaining approval of the plan from the U.S. Department of Justice pursuant

to section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A.

§ 1973c, and Sp lementity the new plan. These schedules will be due 21 days

from the date of this order and must provide that the development, approval,

and implementation of the plans will all be completed by January 1, 1987.

The only question that remains is whether all scheduled elections

should be postponed until such time as they may be conducted in accordance

with the new plans. Many of the considerations leading the court to refuse

to order immediate implementation of new plans also lead it to refuse to

postpone the scheduled elections. Moreover, without having alternative

election plans ready to be implemented immediately, the court is unwilling

to enjoin the scheduled elections. Numerous unforeseen events could delay

the implementation of alternative plans, ranging from disagreement over

where district lines should be drawn to failure to get approval from the

Department of Justice. Given that five different counties are involved and

YY

that the counties' election systems may all have to be completely

reorganized, there can be no absolute assurance that new plans will be fully

implemented before January 1987, when some of the present commissioners’

terms will end. The court does not wish to be left in the position of

having either to extend the terms of incumbents or to appoint temporary

replacements to serve until the new plans are in place. Both alternatives

would effectively deny the entire electorate the right to vote and thus seem

to offend basic principles of representative government.

The court cautions the counties, however, that they should not

take the preceding statements as a suggestion that the court will easily

entertain and grant extensions of the January 1 deadline. Om the present

record, the court fully expects that all five counties will develop new,

nondiscriminatory election plans and hold elections under those plans by the

first of next year.

B. Irreparable Injury to the Plaintiffs

The plaintiffs have clearly satisfied the seccmd requirement for a

preliminary injunction, which is that they will suffer irreparable harm

unless they obtain immediate relief. An injury is irreparable "4f it cannot

t

be undone through monetary remedies." Deerfield Medical Center v. City of

Deerfield Beach, 661 F.2d 328, 338 (5th Cir. Nov. 13, 1981) (Unit B). The

injury alleged here is denial of the right to vote. As the Supreme Court

recognized long ago, the right to vote is "'a fundamental political right,

because preservative of all rights.' ... [E]ach and every citizen has an

inalienable right to full and effective participation im the political

processes of his State's legislative bodies.” Reynolds v., Sims, 377 C.S.

28

533, 562, 565, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 1381, 1383 (1964) (citation omitted). Given

the fundamental nature of the right to vote, monetary remedies would

obviously be inadequate in this case; it is simply not possible to pay

someone for having been denied a right of this importance. Cf. Elrod v.

Burns, 427 U.S. 347, 373, 96 S.Ct. 2673, 2690 (1976) ("[tlhe loss of First

Amendment freedoms, for even minimal periods of time, unquestionably

constitutes irreparable injury"). Therefore, as this court observed in

Harris I, plaintiffs seeking preliminary injunctive relief under section 2

"should not be and are not required to make the usual showing of irreparable

injury as a prerequisite to relief; rather, such injury is presumed by law."

593 ¥. Supp. at 133,

C. Relative Harms

The court also concludes that the plaintiffs have met the third

requirement for preliminary injunctive relief, which is that the benefits to

the plaintiffs of preliminary injunctive relief outweigh any possible harm

to the counties. To be sure, the relief imposed will inconvenience five of

the counties in some measure, for the counties will have to proceed

immediately with development of new plans. However, the administrative

burden on the five counties cannot begin to compare with the further

subjection of black citizens of the counties to denial of their right to

full and equal political participation beyond January 1, 1987, the date by

which the court believes the counties can reasonably implement new election

plans. The latter alternative is morally as well as legally indefensible.

«20.

D. Public Interest

Finally, the plaintiffs have met the fourth requirement. for

preliminary injunctive relief. Without question, the public interest would

not be harmed by the preliminary injunctive relief awarded today. Section

2, as amended, represents "a strong national mandate for the immediate

removal of all impediments, intended or not, to equal participation in the

election process. Thus, when section 2 is violated the public as a whole

suffers irreparable injury." Harris I, 593 F. Supp. at 135. The public

interest, therefore, mandates the relief afforded by the court today.

IV. RES JUDICATA

Three of the defendant counties--Coffee County, Pickens County,

and Talladega Connty-snbtntain that all of the claims against them are due

to be dismissed from this lawsuit on the grounds of res judicata. Coffee

and Talladega Counties' defenses of res judicata lack merit completely.

Pickens County's res judicata defense has merit, but in part only. The

defense has merit as to the plaintiffs' section 2 intent claim but not as to

their section 2 results claim. Furthermore, as indicated earlier, Pickens

County's defense prohibits the plaintiffs from securing preliminary

injunctive relief against the county; this result obtains because the

premise for the plaintiffs' preliminary injunctive request is limited to the

barred claim.

30

A. Pickens County

In Nevada v. United States, D.S. s y 3103 'S.Ce. 2906,

2918 (1983), the Supreme Court explained that

the doctrine of res judicata provides that

when a final judgment has been entered on the

merits of a case, '[i]t is a finality as to

the claim or demand in controversy, concluding

parties and those in privity with them, not

only as to every matter which was offered and

received to sustain or defeat the claim or

demand, but as to any other admissible matter

which might have been offered for that

purpose.’ ... The final 'judgment puts an

end to the cause of action, which cannot again

be brought into litigation between the parties

upon any ground whatever.'"

In order for res judicata to apply, the prior judgment must have been

rendered by a court of competent jurisdiction, there must have been a final

judgment on the merits, the parties or those in privity with them must be

identical in both suits, and the same cause of action must be involved in

both suits. Rav v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 677 F.2d 818 (llth Cir.

1987), cert. denied, 439 U.S5. 1147, 103 S.Ct. 788 (1983).

According to Pickens County, the question of whether Pickens

County intentionally discriminated against black voters through the use of

an at-large system for electing commissioners was decided in the Corder v.

Kirksey litigation. Corder v. Kirksey (Corder IV), 688 F.2d 991 (5th Cir.

1982) (per curiam) (Former Fifth), cert. denied, 460 U.S. 1013, 103:8.Ct.

1253 (1983); Corder v,. Kirksey {Corder ITI), 639 F.24 1191 (5th Cir. March

16, 1981); Corder v. Kirksey (Corder II), 625 F.2d 520 (5th Cir. 1980)

~-31l-

(per curiam); Corder v. Kirksey (Corder I), 5385 F.24 708 (5th Cir. 1978).

In Corder, black residents of Pickens County challenged the constitu-

tionality of the at-large method of electing county commissioners and school

board members; as the present plaintiffs apparently concede, the litigation

focused on the question of racially discriminatory intent. After years of

litigation, including several appeals, the appellate court finally affirmed

the district court's finding that the plaintiffs had failed to prove

discriminatory intent. Corder IV, supra; Corder III, supra.

The plaintiffs in the present action appear to concede that the

prior suit against Pickens County resulted in a final judgment on the merits

rendered by a court of competent jurisdiction and that the parties in the

: 8 a

two suits were the same. However, the plaintiffs argue that because they

raise a section 2 claim of intentional discrimination while the Corder

plaintiffs raised a constitutional claim of intentional discrimination, the

two suits simply do not involve the same cause of actiem.

8. The plaintiffs in Corder were the class of black residents of

Pickens County; the plaintiffs here are the class of black citizens of

Pickens County. There is obviously considerable overlap between the two

classes. To the extent that any of the present plaintiffs were for some

reason not members of the plaintiff class in Corder, they are nonetheless

bound because their interests are so closely related to those of the Corder

plaintiffs. "Under the federal law of res judicata, z person may be bound

by a judgment even though not a party if one of the parties to the suit is

so closely aligned with his interests as to be his virtual representative."

Aerojet-General Corporation v. Askew, 511 F.2d 710, 719 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 423 U.S. 908, 96 85.Cr, 210 (1975).

32

The former Fifth Circuit recognized that "the principal test for

comparing causes of action is whether the primary right and duty or wrong

are the same in each action." Kemp v. Birmingham News Co., 608 F.2d 1049,

1052 (5th Cir. 1979). In chis case, it is clear that the primary rights and

duties are the same. Despite the nominal difference between the claim in

Corder and that raised here, the plaintiffs in both suits were asserting the

same right--namely, the right to be free from intentional racial

discrimination. See Nilsen v. City of Moss Point, 701 F.2d 556 (5th Cir.

1983) (en banc) (res judicata bars plaintiff's claims of sex discrimination

in suit based on fourteenth amendment because she had previously brought

same claims under Title VII). Furthermore, the Eleventh Circuit has more

recently explained that the bar of res judicata "extends not omiy to the

precise legal theory presented in the previous 1ictgation, but to all legal

theories and claims arising out of the same 'operative nucleus of fact."

Olmstead v. Amoco Oil Co., 725 F.2d 627, 629 (llth Cir. 1984). Since the

plaintiffs in both suits challenged the same election system im the same

county, it would appear that their claims did arise out of the identical

"operative nucleus of fact." The principles of res judicata may therefore

apply regardiess of the fact that the plaintiffs in the first suit relied on

the constitution, whereas the plaintiffs in the present suit rely on section

2 ~ 0

The present plaintiffs also argue that their section 2 intent

claim is not barred by res judicata because the applicable law has changed

since the Corder litigation. In general, "changes in the law after a final

33

judgment do not prevent the application of res judicata and collateral

estoppel, even though the grounds on which the decision was based are

subsequently overruled." Precison Air Parts, Inc. v. Aveo Corp., 736 F.2d

1499, 1503 (11th Cir. 1984), cert. denied, 3.8. s 105 8.Ct. 965

(1985). However, the former Fifth Circuit recognized an exception to that

rule in cases involving constitutional law. 'Faced with changing law,

courts hearing questions of constitutional right cannot be limited by res

judicata. If they were, the Constitution would be applied differently in

different locations." Parnell v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 563 F.2d 180,

185 (5th Cir. 1977), cert. denied, 438 U.S. 915, 98 S.Ct. 3144 (1978). See

also Jackson v. DeSoto Parish School Bd., 585 F.2d 726 (5th Cir. 1978); Moch

v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd., 548 F.2d 594 {5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 434 U.S. 859, 98 S.Ct. 183 (1977). This exception applies to cases

involving section 2 as well. Kirksey v. City of Jackson, 714 F.24 42, 44

(5th Cir. 1983). The plaintiffs may therefore be able to escape the

application of res judicata by demonstrating that the relevant law has

undergone "momentous ... [and] significant" changes since the Corder

litigation concluded. Precision Air Parts, Inc., 736 F.2d at 1504,

The changes in the law upon which plaintiffs rely are the 1982

amendments to section 2. While these amendments were indeed quite

significant, they actually had little effect on the charge of intentional

discrimination presented here and therefore do not bar application of res

judicata.

34

Before the 1982 amendments, a plaintiff challenging at-large

systems had to prove that the system was created or maintained with the

intent to discriminate. City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct.

1490 (1980). After the 1982 amendments, by contrast, a plaintiff could

prevail on a section 2 claim by showing either that the challenged practice

was motivated by a discriminatory intent or that the practice had

discriminatory results. To the extent the plaintiffs in the present action

seek to pursue a claim based on intent rather than results, the 1982

amendments had no practical effect on their position. A plaintiff bringing

a results case essentially had an entirely new cause of action, Kirksey wv.

City of Jackson, 714 F.2d at 44; whereas, a plaintiff pursuing an intent

theory could as easily have brought the claim before the 1982 amendments.

Indeed, the Fifth Circuit twice remanded Corder to the district court so

that that court could reexamine the evidence on intent, Corder II, supra;

Corder I, supra; and on the second remand the appellate court specifically

directed the district judge to "entertain any application plaintiffs may

care to make to present further evidence" on the intent issue. Corder II,

625 F.2d at 521. Admittedly, there is dicta in this circuit to the effect

that a plaintiff might not have been able to bring a vote dilution claim at

all under section 2 prior to the 1982 amendments, McMillan v. Escambia

County, Fla. (Zscanbia I), 638 F.24 1239,. 1243 n, 9 {5th Cir. Feb. 19,

1981), cert. dismissed sub nom. City of Pensacola v. Jenkins, 453 U.S. 946,

102 S.Ct. 17 (1981), but a plaintiff could have brought the identical claim

under the fourteenth amendment at any sine.” City of Mobile v. Bolden,

9. Prior to its amendment in 1982, there was some question as to

whether section 2 permitted a challenge to an (footnote 9 continues)

«35

supra. The mere fact that section 2 was amended in 1982 is therefore not

sufficient to bar the application of res judicata to the present claim of

intentional discrimination.

The plaintiffs’ third argument against the application of res

judicata to their section 2 intent claim is that during the Corder

litigation, a plaintiff simply could not present the type of historical

evidence used here. This argument is without merit. In Arlington Heights,

the Supreme Court explicitly endorsed the use of historical evidence and

legislative histories for the purpose of demonstrating discriminatory

intent. 429 U.S. at 267-68, 97 S.Ct. at 564-65. Arlington Heights was

decided in 1977, one vear before the first remand of the Corder suit. While

the usual method of proving intentional voting discrimination was to satisfy

a number of criteria laid out in Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th

Cir. 1973) (en banc), aff'd on other grounds sub nom. East Carroll Parish

School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636, 96 S.Ct. 1083 (1976), there was

nothing to prevent the plaintiffs from attempting to present an alternative

form of proof. Indeed, the second appeals court decision in Corder made

clear that after City of Mobile v. Bolden plaintiffs might have to do more

than merely satisfy the Zimmer factors in order to prevail; Corder II almost

(footnote 9 continued) at-large system. Escambia I, 638 F.24 at 1243 nn. 9.

However, there is no question that the 1982 amendments now permit such a

challenge. United States v. Marengo County Commission, 731 F.2d 1546, 1556

(11th Cir.), cert. denied, > U.8, ., 105:.8.Cr. 375 (1984). See also

Lee County Branch of NAACP v. City of Opelika, 748 F.2d at 1479; Escambia

II, 748 F.2d at 1046; S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted in

1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 177; H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., Ist

Sess.

«3fw

invited the plaintiffs to attempt an alternative approach. Corder II, 625

F.2d at 521. The plaintiffs have pointed to no particular development in

the law since the Corder litigation that makes it possible for them to use

evidence that they could not have used previously.

The final argument against applying res judicata to the

plaintiffs' section 2 intent claim is that it would be unjust and against

public policy to do so. The court is particularly concerned by two

considerations. First, the rights at stake here are fundamental and are

being denied to a large group of individuals; application of res judicata

principles in this case could well preclude an entire class of black

citizens from enjoying a basic constitutional right on an equal basis with

white citizens. Second, since the court has already found a discriminatory

intent on the part of the state that was manifested through the county

election schemes, it seems somewhat anamolous to dismiss the intent claim

against Pickens County; the state's discriminatory purposes were certainly

carried out in Pickens County to the same extent as they were in the other

counties involved in this suit.

The court is also reluctant to use the bar of res judicata for

policy reasons. As the legislative history to the 1982 amendments makes

clear, Congress intended to eradicate as soon as possible all racial

discrimination, both intentional and unintentional, in the area of voting

rights. Applying the bar of res judicata despite a finding of intentional

discrimination by the state could be viewed as frustrating Congressional

policy.

“37

Despite these concerns founded on both justice and public policy,

the court concludes that it has little choice but to dismiss the intent

claim against Pickens County on the grounds of res judicata. In Federated

Department Stores, Inc. v. Moitie, 452 U.S. 394, 101 S.Ct. 2424 (1981), the

Supreme Court held that res judicata bars relitigation of an unappealed

adverse judgment even though other plaintiffs in similar actions against

common defendants had actually prevailed on appeal. In reaching this

conclusion, the Court explicitly rejected the argument that a court may

refuse to apply the res judicata doctrine merely because it believes that

injustice might result. According to the Court,

"Simple justice" is achieved when a complex

body of law developed over a period of years

is evenhandedly applied. The doctrine of res

judicata serves vital public interests beyond

any individual judge's ad hoc determination of

the equities in a particular case. There is

simply "mo principle of law or equity which

sanctions the rejection by a federal court of

the salutary principle of res judicata."

Federated Department Stores, 452 U.S. at 401, 101 S.Ct. at 2429 (citation

omitted).

The mere fact that a suit involves a large number of plaintiffs

claiming a deprivation of their rights also makes little difference. Im

Nevada v. United States, U.S. » 103 S.Ct. 2906 (1983), the Supreme

Court held that an entire Indian tribe was barred from litigating a water

rights claim on the ground of res judicata. Furthermore, a judgment in a

class action will generally bind all members of the class, even in civil

rights cases, see, e€.g., Gilchrist v. Bolger, 733 F.2d 1551, 15356 n. 4 (llth

Cir. 1984); Kemp v. Birmingham News Co., 608 F.2d 1049, 1054 (5th Cir.

1979); the size of the class apparently makes little difference. The fact

that a plaintiff asserts a fundamental constitutional right also does not

38.

affect the application of res judicata. See, e.g., Harmon v. Berry, 776

F.2d 259 (llth Cir. 1985) (per curiam) (prisoner's claim of denial of access

to court dismissed on grounds of res judicata); Jones v. Texas Tech

University, 656 F.2d 1137 (5th Cir. Sept. 25, 1981) (Unit A) (due process

claim dismissed on grounds of res judicata); Kemp v. Birmingham News, 608

F.2d 1049 (5th Cir. 1979) (Title VII claim of race discrimination in

employment practices dismissed on grounds of res sudteata).}?

The court is also barred from creating an exception to res

judicata on the grounds of public policy. First, Federated Department

Stores makes clear that res judicata is to be given weight as a public

policy in its own right.

The Court of Appeals' reliance on "public

policy" is ... misplaced. This Court has long

recognized that "public policy dictates that

there be an end of litigation; that those who

have contested an issue shall be bound by the

result of the contest, and that matters once

tried shall be considered forever settled as

between the parties.” ... [The] "doctrine of

res judicata is not a mere matter of practice

10. The three more recent decisions of the former Fifth Circuit

in which the court found an exception to res judicata based on

considerations of justice do not help the present plaintiffs. Admittedly,

in Parnell v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 563 F.24 1380, 185 (5th Cir. 1977),

cert. denied, 438 U.S. 915, 98 S.Ct. 3144 (1978), the court refused to apply

res judicata because, among other reasons, "[t]o bind forever class members

to a deprivation of their constitutional rights because some class members

failed to enter enough evidence to meet their burden of proof is unjust."

However, in light of Gilchrist and Kemp, in which class members were bound

by res judicata, it appears that the e Eleventh Circuit has abandoned the

Parnell dicta. In both Jackson v. DeSoto Parish School Bd., 585 F.2d 726

(5th Cir. 1978), and Moch v. East Baton Rouge Parish School ie. 548 F.24

5094 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 859, 98 S.Ct. 183 (1977), on the

other hand, the court found that it would be unjust to apply res judicata

because the applicable law had undergone a significant change. No such

injustice threatens here, of course, because any change in the applicable

law did not directly affect plaintiffs' intent claim against Pickens County.

30

or procedure inherited from a more technical

time than ours. It is a rule of fundamental

and substantial justice, 'of public policy and

of private peace,' which should be cordially

regarded and enforced by the courts.”

Federated Department Stores, 452 U.S. at 401, 101 S.Ct. at 2429 (citations

omitted). Furthermore, courts have frequently applied res judicata where

policies equally important as those embodied in section 2 were at stake.

See, e.g., Kemp v. Birmingham News, 608 F.2d 1049 (5th Cir. 1979) (Title

vil).

The court therefore concludes that the intent claim against

Pickens County must be dismissed because of the Corder litigatiom. The