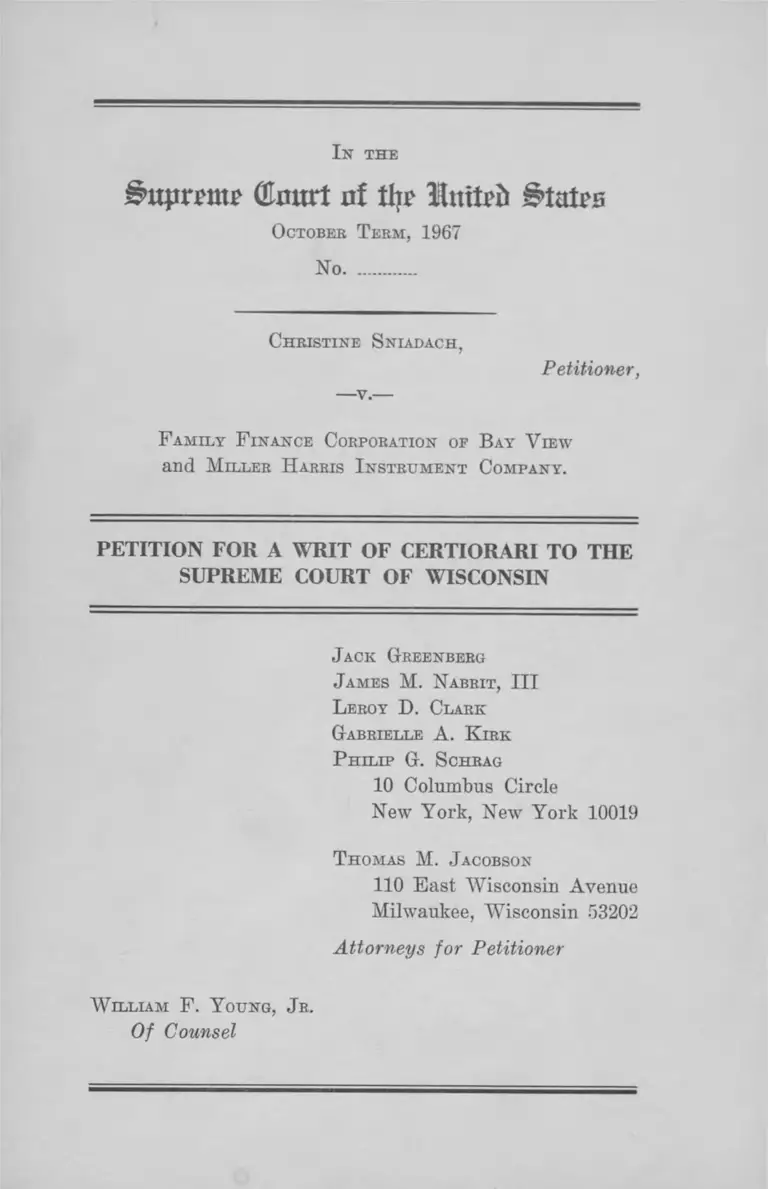

Sniadach v Family Finance Corp Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

February 27, 1968

79 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sniadach v Family Finance Corp Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1968. 3ed2b6d3-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c4dbc902-8077-4027-a20f-fb1b835de0c6/sniadach-v-family-finance-corp-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

i5>ttpnmtr (Enurt of tip United States

October T erm, 1967

No..............

Christine S niadach,

Petitioner,

— v.—

F amily F inance Corporation of B ay V iew

and M iller H arris I nstrument Company.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF WISCONSIN

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

L eroy D. Clark

Gabrielle A. K irk

P hilip G. S chrag

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

T homas M. Jacobson

110 East Wisconsin Avenue

Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53202

Attorneys for Petitioner

W illiam F. Y oung, Jr.

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Decisions Below ............................................ 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

Question Presented ............................................................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 2

Statement ............................................................................. 3

How the Federal Question Was Raised and Decided

Below ............................................................................... 4

R easons foe Granting the W r it :

I. Certiorari Should be Granted to Review an

Issue of National Importance: The Widespread

Use of Pre-Judgment Wage Garnishments to

Compel Wage Earners to Make Favorable

Settlements With Their Alleged Creditors

Without Hearing or Trial .................................. 6

II. The Wisconsin Procedure for Obtaining Pre-

Judgment Wage Garnishments Deprives Em

ployees of Due Process of Law .......................... 13

Conclusion 22

A ppendix A :

Order to Show Cause.................................................... la

Affidavit of Thomas M. Jacobson ........................ 2a

Order of County Court .......................................... 3a

Notice of Appeal to Circuit C ourt.......................... 5a

Order of Circuit Court ............................................ 6a

Notice of Appeal to Supreme C ourt....................... 7a

Memorandum Decision of Circuit Court ............... 8a

Opinion of Supreme Court of Wisconsin ............ 17a

Dissenting Opinion of Supreme Court of Wis

consin ........................................................................ 33a

Motion for Rehearing Denied ................................. 43a

A ppendix B :

Statutory Provisions Involved ................................. 44a

11

PAGE

Ill

T able of A uthorities

Cases: page

Byrd v. Rector, 112 W.Va. 192, 163 S.E. 845 (1932)

5,19, 20

Coe v. Armour Fertilizer Works, 237 U.S. 413 (1915) 14

Coffin Bros. v. Bennett, 277 U.S. 29 (1928) .................14,18

Coffin Bros. v. Bennett, 164 Ga. 350,138 S.E. 670 (1927) 18

Ewing v. Mytinger & Casselberry, Inc., 339 U.S. 594

(1950) ............................................................................... 15

Grannis v. Ordean, 234 U.S. 385 (1914) ....................... 15

Hovey v. Elliot, 167 U.S. 409 (1897) ............................. 15

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 U.S. 123 (1951) ...................................................... 15

Mclnnes v. McKay, 127 Me. 110, 141 A. 699 (1928) ....18, 20,

21

McKay v. Mclnnes, 279 U.S. 820 (1928) ....................... 18

Noble State Bank v. Haskell, 219 U.S. 104 (1911) ....... 21

Ownbey v. Morgan, 256 U.S. 94 (1921) ......................... 17

Scbroeder v. New York, 371 U.S. 208 (1962) ............... 15

Windsor v. McVeigh, 93 U.S. 274 (1876) ..................... 15

Statutes:

Ark. Stats. Ann. §31-501 (1947) ....................................... 16

Mont. Rev. Codes Ann. §93-4304 (1947) ....................... 16

Nev. Rev. Stat. §31.010 (1965) ........................................ 7

IV

N. C. Gen. Stat. Ann. §1-440.2 (1963) ............................ 7

N. C. Gen. Stat. Ann. §1-440.3 (1963) ............................ 7

Ohio Rev. Code §2715.11 (1953) ...................................... 7

S. D. Code §37.2802 (1939) .............................................. 7

Tenn. Code Ann. §23-601 (1955) ................................... . 7

Wis. Stat. Ann. §267.01 (1967 Pocket Part) ............. 3

Wis. Stat. Ann. §267.02 (1967 Pocket Part) ......3,6,7,18

Wis. Stat. Ann. §267.04 (1967 Pocket Part) ............. 6

Wis. Stat. Ann. §267.05 (1967 Pocket Part) ............. 3,6

Wis. Stat. Ann. §267.07 (1967 Pocket Part) ............. 3, 7

Wis. Stat. Ann. §267.13 (1967 Pocket Part) ............. 3

Wis. Stat. Ann. §267.16 (1967 Pocket Part) ............. 3, 7

Wis. Stat. Ann. §267.18 (1967 Pocket Part) ............. 3,7

Wis. Stat. Ann. §267.20 (1967 Pocket Part) ............. 3

Other Authorities:

Annunzio, Testimony to House Subcommittee on Con

sumer Affairs, Hearing on the Consumer Credit

Protection Act (1967) .................................................. 12

Bare, Testimony to House Subcommittee on Consumer

Affairs, Hearings on the Consumer Credit Protec

tion Act (1967) ............................................................. 9,11

Brunn, Wage Garnishment in California: A Study

and Recommendations, 53 Cal. L. Rev. 1214 (1965) 12

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Fact Sheet No. 4-F, Debt

Pooling and Garnishment in Relation to Consumer

Indebtedness (1966) ...................................................... 12

PAGE

V

Caplovitz, The Poor Pay More (1967 ed.) ................... 20

Fisher, How Garnisheed Workers Fare Under Arbi

tration, Monthly Labor Review (Dept, of Labor,

May, 1967) ....................................................................... 9

Gonzales, Con. Rec. (Feb. 1, 1968) ................................ 21

Halpern, Cong. Rec. (Feb. 1, 1968) .............................. 9

Jablonski, “Wage Garnishment as a Collection De

vice,” 1967 Wis. L. Rev. 759 .................................. 7, 8,10

Jackson, Testimony to the House Subcommittee on

Consumer Affairs, Hearings on the Consumer Credit

Protection Act (1967) .................................................. 11

Jacob, Usage of Wage Garnishment and Bankruptcy

Proceedings in Four Wisconsin Cities, address de

livered to the American Political Science Associa

tion, September, 1966 .................................................... 9

Milwaukee Journal, December 10, 1966, §1, at 17, col. 4 10

National Industrial Conference Board Studies In Per

sonnel Policy, No. 194 (1964) .................................... 10

Note, Garnishment in Kentucky— Some Defects, 45

Ky. L. J. 322 (1956) ...................................................... 9

President Lyndon Johnson, Message to Congress on

Poverty, March 14, 1967 .............................................. 8

Report No. 1040, House Committee on Banking and

Currency, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. (1967) ..................... 12

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders (Bantam ed. 1967) .................................... 6

Reuss, Cong. Rec. (Feb. 1, 1968) ................................. . 13

Sullivan, Cong. Rec. (Feb. 1, 1968) .............................. 11

Wirtz, Testimony to the House Subcommittee on Con

sumer Affairs, Hearings on the Consumer Credit

Protection Act (1967) .................................................. 10

PAGE

I n t h e

(ftmtrt nf tlw Itnitrti g ’tatpa

October T erm, 1967

No..............

Christine S niadach,

Petitioner,

— v.—

F amily F inance Corporation of B ay V iew

and M iller H arris I nstrument Company.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF WISCONSIN

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Wisconsin entered

in the above-entitled case on December 8, 1967, rehearing

of which was denied February 27, 1968.

Citation to Decisions Below

The order of the Milwaukee County Court of Wisconsin

(R. 118-120) is unreported and is set forth in the appen

dix, infra, p. 3a. The memorandum decision of the Mil

waukee Circuit Court of Wisconsin (R. 101-110) is un

reported and is set forth in the appendix, infra, p. 8a.

The decision of the Supreme Court of Wisconsin (R. 126-

148) is reported at 37 Wis.2d 163, 154 N.W.2d 259 (1967),

and is set forth in the appendix, infra, p. 17a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Wisconsin was

entered on December 8, 1967 (R. 126). Rehearing was

denied on February 27, 1968 (R. 150).

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1257(3), petitioner having asserted below, and as

serting here, deprivation of rights secured by the Consti

tution of the United States.

Question Presented

Petitioner is a $65.00 per week wage earner. Half the

wages due her were garnisheed before trial by plaintiff in

a lawsuit against her. Under Wisconsin law, before peti

tioner’s wages were garnisheed, she had no right to notice

and hearing or other procedure for challenging the legal

ity of the garnishment sought by plaintiff. The plaintiff

did not have to show that without garnishment, he would

be unlikely to obtain jurisdiction over petitioner or to

collect a money judgment, nor did he have to show prob

able cause to believe that petitioner owed him any money,

nor any other reason purporting to justify denial of no

tice and hearing. Does this procedure deny due process

of law secured by the Fourteenth Amendment?

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved 1 2

1. This case involves the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case involves Wis. Stats. Sections 267.01, 267.02,

267.05, 267.07, 267.13, 267.16, 267.18, 267.20 (1967 Pocket

Part). They are set forth in the appendix infra, p. 44a.

3

Statement

Petitioner Christine Sniadach is a wage earner and resi

dent of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The Family Finance Cor

poration of Bay View (respondent here), alleging to be

her creditor, commenced an action against her for $420.00

in the Wisconsin courts.1 It also took advantage of the

Wisconsin garnishment law, Wis. Stats. Sections 267.01

et seq., to garnishee the wages due her from her employer.

All plaintiff did to garnishee petitioner’s wages, and all it

had to do, was file an attorney’s affidavit with the clerk

of the County Court, alleging that a summons had been

issued in an action by plaintiff against defendant, and

that the action was founded upon a promissory note. The

statute does not require an allegation that the defendant

is about to leave the jurisdiction, that an attachment is

necessary to obtain jurisdiction, or that but for the gar

nishment the plaintiff may be unable ultimately to have

execution upon a judgment, or any other reason purport

ing to justify denial of notice and prior hearing. The

clerk of the court, on the basis of an attorney’s affidavit,

ordered petitioner’s employer to withhold wages due peti

tioner.

On November 22, 1966, pursuant to the clerk’s summons,

petitioner’s employer, the Miller Harris Instrument Co.,

withheld wages due petitioner in the sum of $31.59 and

continues to withhold them. At no point has petitioner

been granted a hearing on whether or not the garnish

ment was proper, and the statute affords her none until

the main action is tried. 1

1 The claim for $420.00 has not yet been decided because it has

been stayed pending the outcome of this proceeding involving Wis

consin’s pre-judgment garnishment law.

4

How the Federal Question Was Raised

and Decided Below

Petitioner sought by order to show cause in the County

Court to dismiss the garnishment on the ground that the

Wisconsin procedure for pre-judgment garnishment de

prived her of due process of law under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution. Her attorney

alleged that the proceedings were “ in violation of defen

dant’s constitutional rights under . . . the United States

Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment, in that defendant is

being deprived of her property without due process of

law.” Affidavit of Thomas M. Jacobson, dated December

22, 1966 (R. 117). On January 7, 1967, Judge Thaddeus

Pruss of the County Court held that “ the garnishment

action in the instant proceedings does not violate defen

dant’s constitutional rights under . . . the United States

Constitution 14th Amendment due process and equal pro

tection” (R. 119).

On appeal to the Circuit Court of Milwaukee, petitioner

argued that the garnishment statute “ deprives the defen

dant of due process of law in violation of the fourteenth

amendment to the United States Constitution because the

defendant is given no hearing before being deprived of

his property.” The Circuit Court affirmed on March 15,

1967, stating that “ [defendant's argument rejects the fact

that nothing has happened to the defendant’s title except

it is temporarily in suspension pending a final adjudica

tion on the debt owed the plaintiff” (R. 105).

In the Supreme Court of Wisconsin, petitioner again

argued that the garnishment procedure violated due proc

ess of law guaranteed to her by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Federal Constitution. On December 8, 1967,

5

the Supreme Court of Wisconsin affirmed the decision be

low holding that “Wisconsin’s garnishment before judg

ment statutes do not deprive appellant of her property

without due process of law” (R. 134). The Court quoted

with approval the language of Byrd v. Rector, 112 W.Va.

192, 163 S.E. 845 (1932):

[A] defendant is not deprived of his property by rea

son of the levy of a copy of the attachment upon a

person who is indebted to him or who has effects in

his custody belonging to the defendant. The most that

such procedure does is to deprive defendant of the

possession of his property temporarily by establish

ing a lien thereon . . . Until [a final] judgment is

obtained, the defendant’s property in the hands of a

garnishee is immune from the plaintiff’s grasp . . .

(R. 134).

Two justices of the Wisconsin Supreme Court dissented,

arguing that the reasoning of the majority was “most

unrealistic. The constitutional question is not whether

defendant has lost his title to the property, nor whether

another has gained its beneficial use. The test is whether

he was deprived of his property” (R. 141) (emphasis in

original).

G

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Certiorari Should be Granted to Review an Issue of

National Importance: The Widespread Use of Pre-

Judgment Wage Garnishments to Compel Wage Earners

to Make Favorable Settlements With Their Alleged Cred

itors Without Hearing or Trial.

“ Garnishment practices in many states allow creditors

to deprive individuals of their wages through court action

without hearing or trial. In about 20 states, the wages

of an employee can be diverted to a creditor merely upon

the latter’s deposition, with no advance hearing where the

employee can defend himself. He often receives no prior

notice of such action and is usually unaware of the law’s

operation and too poor to hire legal defense.” Report of

the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders 276

(Bantam ed., 1968).

These words from the “Riot Commission” Report define

the problem in this case. In a garnishment proceeding

before judgment, a creditor or alleged creditor is per

mitted to cause the wages of his alleged debtor to be

turned over to the court or held by the employer pending

the outcome of the main litigation between creditor and

debtor. In Wisconsin an alleged creditor may avail him

self of this preliminary remedy simply by alleging that

the debtor owes him a sum due under a contract, Wis.

Stats., Sections 267.02, 267.04, 267.05; he need not allege

that the defendant is a nonresident, or is about to leave

the jurisdiction, or has no property in the state other than

his wages, or that an attachment is necessary, or anything

else purporting to justify denial of notice and prior hear

7

ing in order to obtain jurisdiction over the defendant. The

debtor-defendant need not be notified that his wages have

been garnisheed until 10 days after the garnishment. Wis.

Stats. Section 267.07. The validity of the garnishment may

not be tested until after the main action between plaintiff

and defendant is tried. Wis. Stats. Section 267.16. The

wages for only one salary period are subject to garnish

ment, Wis. Stats. Section 276.02, and the defendant is

entitled to receive from his employer a “ subsistence allow

ance” of $25 or $40 if he has dependents (in no event to

exceed 50% of the wages withheld), but this allowance is

fixed at the specified levels regardless of whether the wages

garnisheed are those owing for a week or a month, Wis.

Stats. Section 267.18, and in any event, is “generally in

sufficient to support the debtor for any one week.” Jablon-

ski, “Wage Garnishment as a Collection Device,” 1967 Wis.

L. Rev. 759, 767. Of forty-one jurisdictions permitting

some sort of pre-judgment garnishment, only seventeen

states, including Wisconsin, permit alleged creditors to

deprive workers of their earnings without either a prior

hearing or the demonstration of some special circumstances

justifying summary relief.2 In these seventeen states, pre

judgment garnishment is used routinely by finance com

panies as a device to compel payments of debts; pre

judgment garnishment is more properly characterized as

a collection device than as a provisional remedy. See

2 In the other twenty-four jurisdictions, such garnishments are

obtainable only upon a showing by the plaintiff that without the

garnishment, his chance of collecting any judgment he might be

awarded is small. In these jurisdictions, a plaintiff seeking to

garnishee a defendant’s wages must show that defendant is a non

resident, Ohio Rev. Code §2715.11, or that defendant has con

cealed himself with intent to avoid service, Gen. Stat. of N.C.

§1-440.2-3, or that defendant has absconded, Nevada Revised Stats.

§31.010, or that defendant has secreted his property with intent to

defraud, Tenn. Code Annot. §23-601, or that he has no other prop

erty in the state, S. Dak. Code §37.2802.

8

Jablonski, “ Wage Garnishment as a Collection Device,”

1967 Wis. L. Rev. 759.

Garnishment as a Weapon for Collection

“Hundreds of workers among the poor lose their jobs

or most of their wages each year as a result of garnish

ment proceedings. In many cases, wages are garnished by

unscrupulous merchants and lenders whose practices trap

the unwilling workers.” President Lyndon Johnson, Mes

sage to Congress on Poverty, March 14, 1967. A significant

amount of study has been done on the use and effect of

garnishment, and the results indicate that the President’s

message is, if anything, an underestimation of the seri

ousness of the problem. One study focused on the use of

garnishment in four Wisconsin cities, and found that gar

nishment (particularly pre-judgment garnishment) is used

not only to secure payment of sums legitimately due, but

to force alleged debtors to pay without contesting the debts

in court.

In the four cities studied, money lenders (principally

finance companies) and retailers were the two heaviest

users of wage garnishments . . . Finance companies

have the most developed system of collecting delin

quent accounts. Within 10 days after a payment is

due, they consider the debtor delinquent and begin

efforts to collect. They make use of a large repertoire

of collection methods including overdue notices, tele

phone calls to his employer, calls to cosigners of his

note (if any), repossession of the article purchased

with the loan (if any), and then wage garnishment.

. . . When all other means of reaching the debtor have

failed, garnishments usually succeed in forcing him

to contact the creditor because he finds himself com

pletely out of funds and his job endangered. Many

9

creditors will release the pay check to the debtor after

a token payment plus the promise of modest weekly

payments until the debt is repayed. The threat of

another garnishment is used to force the debtor to

complete his payments. H. Jacob, Usage of Wage

Garnishment and Bankruptcy Proceedings in Four

Wisconsin Cities, address delivered to the American

Political Science Association, September, 1966, pp.

7, 10.

Garnishment is an effective weapon in the arsenal of

the finance companies not only because “ the individuals

whose wages are being garnished are the very individ

uals whose total wages are required for the payment of

necessary living expenses: food, clothing, shelter, and

medical expenses,” 3 but also because of the widespread

practice among employers of firing workers whose wages

are garnisheed. “ The debtor often may find himself un

employed; employers are often unwilling to accept the

additional expense of administering garnishments.” Re

marks of Congressman Halpern, Cong. Rec., p. H689 (Feb.

1, 1968). “ Some companies regard a single garnishment

as grounds for discharge . . . it is detested as an unmiti

gated nuisance by employers to such an extent that even

union contracts tacitly or specifically recognize the right

of an employer to discharge an employee whose debts

result in more than a prescribed number of garnishments

within a specified period.” Note, Garnishment in Kentucky

— Some Defects, 45 Ky. L. J. 322, 330 (1956). See Fisher,

How Garnisheed Workers Fare Under Arbitration,

Monthly Labor Review (Dept, of Labor, May 1967). Be

3 Testimony of Clive W. Bare, Referee in Bankruptcy, Eastern

District of Tennessee, to House Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs,

Hearings on the Consumer Credit Protection Act (1967).

10

tween 100,000 and 300,000 American workers are fired

from their jobs each year as a result of wage garnish

ments. Testimony of Secretary Willard Wirtz to the

House Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs, Hearings on

the Consumer Credit Protection Act, p. 739 (1967). Thir

teen percent of American manufacturing firms fire workers

whose wages are garnisheed even once. National Industrial

Conference Board Studies In Personnel Policy, No. 194,

p. 38, Table 40 (1964). A study of garnishments in Wis

consin showed that 41% of employees in the sample were

warned of dismissal if they were again garnisheed; 11%

were fired forthwith, and in only 15% of the cases did

the employers try to help the workers. Jablonski, “Wage

Garnishment as a Collection Device,” 1967 Wis. L. Rev.

759, 766, n. 29.

The most gross injustices in cases of discharge as a

result of garnishment occur when the garnishments are

of the pre-judgment type; there the defendant may have

a perfectly good defense to the main lawsuit, or may not

even be a debtor, but because he is denied a prior hearing

he is threatened with being fired before he can contest

the validity of the garnishment. It does not matter to

the employer that the worker is innocent—the nuisance

to the employer and his bookkeepers is as great. Only by

settling immediately with the plaintiff can the employee

remove the garnishment and retain his job security.4

Furthermore, in a significant proportion of the cases,

the underlying debt is subject to a good defense, such as

fraud, but the debtor is never able to raise this defense

because he cannot afford to wait until trial. “What we

4 Cases have been documented in which employees were fired as

soon as their wages were garnisheed, and were able later, at trial, to

show that they were not liable. Milwaukee Journal, December 10,

1966, §1, at 17, col. 4, cited in Jablonski, supra, at 769, n. 42.

11

know from our study of this problem [in the hearings of

the House Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs] is that in

a vast number of cases the debt is a fraudulent one, saddled

on a poor, ignorant person who is trapped in an easy

credit nightmare in which he is charged double for some

thing he could not pay for even if the proper price was

called for, and then hounded into giving up his pound of

flesh, and being fired besides.” Remarks of Congress-

woman Leonor Sullivan, Chairlady of the House Subcom

mittee on Consumer Affairs, Cong. Rec. p. H688 (Feb. 1,

1968). Garnishment “ is mainly the weapon not of the

honest merchant or lender but of the predatory credit

sellers who hook a poor, ignorant worker on credit terms

which are as devastating to that worker as the dope habit

— something he can never seem to lick . . . [W]eep for

the inhumanity exposed [in our hearings] about the sewer

of the so-called easy credit racket—not legitimate business

but the blood suckers of commerce.” Ibid.

Garnishment and Personal Bankruptcies

It has been established beyond doubt that garnishment

— and the accompanying threat of loss of employment—

is the triggering cause of most bankruptcies in the United

States.5 Federal bankruptcy referees have found upon

examination of creditors and debtors that “between 60

and 70 percent of bankruptcy filings are the direct result

of wage garnishments. Many individuals are being driven

into bankruptcy who actually owe relatively small sums,

but whose wages are under attachment.” Testimony of

5 In Fiscal 1967, there were 208,329 bankruptcies filed in United

States District Courts. Testimony of Royal E. Jackson, Chief,

Bankruptcy Division, Administrative Office, U. S. Courts, to the

House Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs, p. 416 (1967). 92% of

them were filed by consumers rather than businesses. Ibid.

12

Clive W. Bare, Referee in Bankruptcy, Eastern District

of Tennessee, to House Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs,

Hearings on Consumer Credit Protection Act, p. 415

(1967). A direct correlation has been found between the

harshness of state garnishment laws and the incidence of

tilings in bankruptcy.6 Bureau of Labor Statistics, Fact

Sheet No. 4-F, Debt Pooling and Garnishment in Rela

tion to Consumer Indebtedness (1966); see Brunn, Wage

Garnishment in California: A Study and Recommenda

tions, 53 Cal. L. Rev. 1214 (1965).

In short, the garnishment procedure is a harsh device

used largely by finance companies to collect debts with

out having to submit to a full hearing in court. Garnish

ments are a great hardship to wage earners, who cannot

afford to lose even 10% or 15% of their wages and still

maintain their families, and who are threatened in many

instances with being fired if they do not settle with their

alleged creditors. As one member of the House Commit

tee on Banking and Currency has stated, “ [ Garnishment

is an expensive, painful procedure which can cost a man’s

job. This has come to the attention of this Committee as

many other Members of Congress. The reports on the

riots in Watts, Chicago and other cities, indicate that it

costs people their lives.” Congressman Frank Annunzio,

in House Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs Hearings on

Consumer Credit Protection Act, p. 104 (1967). And pre

judgment garnishment, by which perfectly innocent em

6 “ In States such as Pennsylvania and Texas, which prohibit the

garnishment of wages, the number of nonbusiness bankruptcies

per 100,000 of population are nine and five, respectively, while

in those States having relatively harsh garnishment laws, the in

cidents of personal bankruptcies range between 200 to 300 per

100,000 population.” Report No. 1040, House Committee on Bank

ing and Currency, 90th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 21 (1967).

13

ployees can be subjected to all the pains and penalties of

wage attachments before they are given a chance to say

a single word in their own defense, is the harshest type

of garnishment. As a Wisconsin Congressman has stated,

“ The idea of wage garnishment in advance of judgment, of

trustee process, of wage attachment, or whatever it is

called is a most inhuman doctrine. It compels the wage

earner, trying to keep his family together, to be driven

below the poverty level.” Remarks of Congressman Henry

Reuss, Cong. Rec., p. H688 (1968).

Petitioner asks that this Court grant the writ prayed

for, because pre-judgment garnishment of petitioner’s

wages is not only an “ inhuman doctrine” ; it is an un

constitutional deprivation of due process of law secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment.

n.

The Wisconsin Procedure for Obtaining Pre-Judg

ment Wage Garnishments Deprives Employees of Due

Process of Law.

The petitioner raises issues concerning only one feature

of the Wisconsin garnishment procedure: Without notice

or hearing it permits wages to be garnisheed before a

judgment in the main action and without any showing by

the plaintiff that he is probably entitled to the money or

that unless the wages are attached, he will be unable to

obtain jurisdiction over the defendant or execution in

satisfaction of a potential judgment, and without any

other purported justification. This case does not involve

a claim that the common procedure of wage garnishment

after judgment is unconstitutional, for with regard to

that situation, there has been at least a finding that the

defendant is indebted to the plaintiff. Petitioner does

14

maintain, however, that pre-judgment garnishments in

Wisconsin are unconstitutional because wage-earners are

given no prior hearing to contest the probable existence

of the debt, the need of the plaintiff for security, or the

validity under state law of the proposed garnishment.7

We start with the proposition that no one may be de

prived of property by state action unless first given notice

and opportunity to be heard. For example, this Court has

struck down a Florida procedure whereby the judgment

creditor of a corporation could issue an execution against

the property of the owner of unpaid stock, without giv

ing that owner notice or a prior hearing. The owner was

held to be “ entitled, upon the most fundamental principles,

to a day in court and a hearing upon such questions as

whether the judgment is void or voidable for want of

jurisdiction or fraud, whether he is a stockholder and

indebted, and other defenses personal to himself.” Coe v.

Armour Fertilizer Works, 237 U.S. 413, 423 (1915). Absent

a prior hearing, the attachment was “ repugnant to the

‘due process of law’ provision of the 14th Amendment,

which requires at least a hearing, or an opportunity to

be heard, in order to warrant the taking of one’s property

to satisfy his alleged debt or obligation . . . ” Ibid.

7 Petitioner submits that a post-garnishment hearing is adequate

protection for alleged debtors in those few cases where the plaintiff

swears that notice of a hearing before the attachment would cause

the defendant to flee the jurisdiction or remove his assets. This

will hardly ever occur, since the defendant’s job and continuing

source of income will always be in the jurisdiction in question in

these cases. In any event, the hearing must take place with rea

sonable promptness, and not be deferred until the trial of the main

action, as in Wisconsin. I f opportunity for a prompt hearing after

such a garnishment existed, the attachment would become “ a mode

only of commencing . . . suits” and would be constitutionally per

missible. Coffin Bros. v. Bennett, 277 U.S. 29, 31 (1928).

15

The requirement of notice8 and the opportunity to be

heard before a deprivation of property is one of the essen

tial features of the American legal process. As Mr. Justice

Frankfurter said in Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee

v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, 164 (1951), notice and hearing

are “prerequisite to due process in civil proceedings.” As

recently as Schroeder v. New York, 371 U.S. 208, 212

(1962), this Court has held the right to be heard in civil

litigation to be “ one of the most fundamental requisites

of due process,” and has even deemed it to be “ the funda

mental requisite” of due process, Grannis v. Ordean, 234

U.S. 385, 394 (1914). See also, Windsor v. McVeigh, 93

U.S. 274, 277, 278 (1876); Hovey v. Elliot, 167 U.S. 409

(1897).

There might be some circumstances, not present here,

which might justify an attachment of a defendant’s prop

erty before judgment and before any hearing. If there is

some evidence that even notice of the hearing may itself

have adverse consequences for the plaintiff, it is reason

able to permit the attachment to be followed by, rather

than preceded by, a hearing for the defendant. If, for

example, the plaintiff swears that he has a basis for be

lieving that the defendant was about to flee the jurisdic

tion of the state, or was removing his assets from the

state, it would be reasonable to permit a summary attach

ment. See Ewing v. Mytinger <£ Casselberry, Inc., 339 U.S.

594, 599 (1950). Such an attachment could particularly be

justified if the alleged creditor had to post a bond to pro

tect the debtor from loss caused by an improper garnish

8 Under the Wisconsin procedure, not even prior notice of the

garnishment proceeding is given to the wage earner; he need not

be served with the garnishment summons until ten days after his

employer is instructed to withhold the wages.

16

ment,9 or if the debtor could recover damages from a

creditor who falsely and maliciously swore that he had

reason to believe the debtor would flee the jurisdiction

before judgment. But Wisconsin requires no bond, or even

a sworn statement of need for summary process.10

Wisconsin provides workers threatened with garnish

ment no prior hearing, requires no showing that a plain

tiff needs emergency summary relief, and then provides

wage earners no hearing at all until the trial (perhaps

years after the garnishment) of the main action. The

statute permits garnishment of the wages of domestic

residents, such as petitioner, without any requirement

that the plaintiff show or even allege that his ultimate

recovery is in jeopardy. Yet few wage-earners are likely

to flee the state upon being sued, and as a practical mat

ter, it is impossible (or nearly so) to transfer from the

jurisdiction the wages due from one’s employer.

We have, therefore, in the Wisconsin procedure, the

practice of denying wage-earners the sums due them, with

out either any adversary process or a special justification

for summary procedure. The only way in which the Wis

consin Supreme Court was able to hold such a procedure

constitutional was to hold that a “ temporary deprivation”

9 Some of the seventeen states permitting pre-judgment garnish

ment without a showing of need for summary relief do require a

plaintiff’s bond to protect the wage earner. See e.g., Mont. Rev.

Code §93-4304; Ark. Stat. Annot. §31-501 (double bond). Due

process might require that summary relief be permitted only upon

both a showing of need and a bond to protect the wage-earner.

Wisconsin requires neither of a plaintiff.

10 Even where a plaintilf filed a sworn statement of need in order

to obtain a summary garnishment without a prior hearing, there

seems no justification for denying the defendant the right to a sub

sequent but prompt hearing, and affording him the opportunity to

dissolve the attachment by showing that the plaintiff was wrong

— that the wage-earner was not in fact preparing to leave or remove

his assets from the state.

17

of property is not a “deprivation” of property. In sup

port of this proposition, it cited three Supreme Court

decisions. But it may he seen that these decisions, none

of which involved the attachment or garnishment of wages,

are more properly viewed as cases dealing with special

justifications of summary attachment, and that the due

process clause of the Constitution is concerned with realities

and not with word-play. The first case cited in the opinion

of the Wisconsin Supreme Court is Ownbey v. Morgan,

256 U.S. 94 (1921). But there the defendant resided in a

foreign state. This Court justified the pre-judgment at

tachment on this basis:

Hence it naturally came about that the American

colonies and states, in adopting foreign attachment

as a remedy for collecting debts due from nonresident

or absconding debtors, in many instances made it a

part of the procedure that if the defendant desired

to enter an appearance and contest plaintiff’s demand,

he must first give substantial security . . . A property

owner who absents himself from the territorial juris

diction of a state, leaving his property within it, must

be deemed ex necessitante to consent that the state

may subject such property to judicial process or to

answer demands made against him in his absence,

according to any practicable method that reasonably

may be adopted. 256 U.S. at 105-111 (emphasis

added).11 11

11 Other language in the Ownbey case indicates that this Court

could not have intended that the principle it was adopting with

regard to foreign debtors should apply to wage garnishments even

of foreign wage earners. The Court used the term “ property” not

in its legal sense but in the ordinary sense of “ substantial wealth” :

Ordinarily [the requirement that a debtor post bond to dis

solve an attachment] is not difficult to comply with— a man

who has property usually has friends and credit— and hence

in its normal operation must be regarded as a permissible con

dition. 256 U.S. at 111.

18

Coffin Brothers v. Bennett, 277 U.S. 29 (1928), is like

wise no authority for the opinion of the Wisconsin Supreme

Court. Justice Holmes, writing for the Court, approved

a Georgia procedure for the attachment of the stock of

liquidated banks. The stock could be attached prior to

any hearing on the propriety of the attachment, even

though the stockholders were domestic residents. But the

opinion of the Georgia Supreme Court makes clear that

attachment in such cases had a very special purpose: the

attachment was necessary in order for plaintiffs to obtain

jurisdiction over defendants.12 But plaintiff in the instant

case did not need to garnishee defendant’s wages to obtain

jurisdiction over her; he had in personam jurisdiction.13

The final authority relied upon by the majority below

is McKay v. Mclnnes, 279 U.S. 820 (1928), a memorandum

decision affirming Mclnnes v. McKay, 127 Me. 110, 141 A.

699 (1928), holding Maine’s attachment before judgment

statute not unconstitutional. The significance of McKay,

as applied to the present case, however, must be open to

some question. McKay was submitted on agreed facts to

the Maine Supreme Court, and it nowhere appeared

whether or not the defendant was a resident of Maine.

12 “ [The statute] does not provide for rendition of judgments

in personam against the stockholders of banks which the superin

tendent of banks has taken control of for the purpose of liquida

tion, but provides only for summary issuance of executions against

stockholders of such banks, as a mode only of commencing against

them suits . . . ” 164 Ga. 350, 138 S.E. 670, 671 (1927).

13 Indeed, it is somewhat hard to discern what legitimate pur

pose underlay plaintiff’s decision to garnishee petitioner’s wages.

It did not need the garnishment for jurisdictional purposes, and

petitioner was a domestic resident with roots in the community,

including local employment. The amount of the garnishment was

only $31.59, which in any event could not afford the plaintiff much

security on his alleged $420.00 debt, particularly in view of the

fact that Wisconsin law permits an alleged creditor to garnishee

wages for one pay period only. Wis. Stats. §267.02(b) (2).

19

This Court’s citation of Oivnbey as authority for its affirm

ance, and its failure to write an opinion, suggests that

the Court may have thought that the facts underlying

McKay were essentially the same as those underlying

Ownbey. But in the present case, the Court is presented

for the first time with the question of the validity of a

pre-judgment attachment (in this case a wage garnish

ment) on the basis of a record showing that the defen

dant’s residence and place of employment were within the

jurisdiction in which the plaintiff brought his suit, and

there is therefore little or no justification for depriving

the defendant of his property without any showing of

probable cause or opportunity for a prior hearing.14

Furthermore, the applicability to this case of precedents

dating even from the 1920’s must be subject to some ques

tion. The precedents cited by the Wisconsin Supreme

Court were suited to borrowers and lenders of substantial

wealth. Debtors who had one bank account attached were

likely to have others on which they could draw, or other

sources of capital; an attachment did not deprive them of

their only source of income. Only since the end of World

War II has America become a consumer credit economy,

in which, quite acceptably, wage-earners are regularly in

14 Byrd v. Rector, 112 W.Va. 192, 163 S.E. 845 (1932), is a

fourth case cited by the Wisconsin Supreme Court which involved

a nonresident defendant sued by an infant plaintiff for having

negligently disposed of a dynamite cap. The Supreme Court of

West Virginia upheld the constitutionality of the attachment, with

out prior hearing, of the defendant’s property. It may be pre

sumed that it would be difficult to collect a judgment from a non

resident. But that precedent was improperly extended by the

Wisconsin Supreme Court to permit garnishment of petitioner’s

wages; the plaintiff here did not allege that the security of any

eventual judgment might be impaired, and since petitioner is a

resident, with employment in Wisconsin, it cannot be presumed

she would flee her job and the State i f plaintiff were successful in

its suit for $420.00.

2 0

debt. The outstanding installment debt has grown from

2.5 billion dollars in 1945 to 75 billion dollars in 1967, and

will exceed 100 billion dollars by 1970. Caplovitz, The

Poor Pay More, xvi (Preface to 1967 edition). Petitioner

submits that the application to garnishments in the 1960’s

of rules of law formulated to govern attachments in the

1920’s further warrants issuance of the writ prayed for,

even were it not for the fact that the 40 year old cases

are all distinguishable.

The remaining argument, then, supporting the validity

of the garnishment is that employees whose wages are gar

nisheed are not “ deprived” of their property because the

“deprivation” is merely temporary; the -wages are held in

escrow until the plaintiff’s main case is tried, and if the

plaintiff is not successful, the garnishment is dissolved.15

But the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment addresses itself not to “drily logical” analysis or

15 This reasoning was relied upon by two supreme courts besides

that of Wisconsin, although Wisconsin’s is the only Supreme Court

to apply it to wage garnishment. The Supreme Court of West

Virginia has reasoned:

The most that such procedure does is to deprive defendant

of the possession of his property temporarily by establishing

a lien thereon. [Until final judgment] there has been no depri

vation of property . . . Until such judgment is obtained, the

defendant’s property in the hands of a garnishee is immune

from the plaintiff’s grasp. Under no circumstances could it be

converted into cash and applied to the plaintiff’s demand

prior to final adjudication of the merits of the controversy

between plaintiff and defendant. Byrd v. Rector, 112 W.Va.

192, 163 S.E. 845 (1932).

And the Supreme Court of Maine, while conceding that “Depriva

tion does not require actual physical taking of the property or

thing itself. It takes place when the free use and enjoyment of

the thing or the power to dispose of it at will are affected,” upheld

pre-judgment attachment by adding “yet conditional and tem

porary it is.” Mclnnes v. McKay, 127 Me. 110, 116, 141 A. 699,

702 (1928).

2 1

“ scholastic interpretation,” see Noble State Bank v. Has

kell, 219 U.S. 104, 110 (1911), but to idealities. And nothing

is more real to a wage earner whose wages have been

garnisheed than impairment of his ability to care for his

family and meet the demands of his other creditors. It

matters little that the plaintiff has no use of the defen

dant’s wages; the important fact is that the defendant has

no use of them. And, unlike attachment of stock or other

assets of a wealthy man, loss of wages to a wage earner

is likely to result in a financial squeeze seriously affect

ing his power to feed, clothe and shelter his dependents.1'

Nor is the “ temporary” nature of the deprivation a satis

factory response; given the time required for discovery

and the crowded condition of court dockets, it may he

years before the main action comes to trial. During this

period, the wage earner loses the difference—measurable

as interest—between the present and future value of the

wages due him. More important, the garnishment, valid

or not, keeps a defendant under pressure to settle the

lawsuit on terms favorable to the alleged creditors, even

if he has a perfect defense. It is no comfort to a wage

earner that, like any attachment, a garnishment “does

not destroy title or the right to sell. Until a sale of exe

cution, the debtor has full power to sell or dispose of

the property attached without disturbing the possession

(in case of personalty) or rights acquired by the attach

ment.” Mclnnes v. McKay, 127 Me. 110, 115, 141 A. 699,

702 (1928). Even in jurisdictions which do not forbid

wage assignments, there is no real market for wages *

16 “ For a poor man— and whoever heard of the wages of the

affluent being attached?— to lose part of his salary often means

his family will go without the essentials. No man sits by while his

family goes hungry or without heat. He either files for consumer

bankruptcy, and tries to begin again, or just quits his job and

goes on relief. Where is the equity, the common sense in such a

process?” Remarks of Congressman Gonzales, Cong. Rec. p. H690

(Feb. 1, 1968).

2 2

currently attached, which the alleged debtor may never

become entitled to. The Wisconsin Supreme Court’s con

ception of what constitutes a “ deprivation” of property is

archaic and unrealistic, ignoring the difference in value

between a sum of money and the right to future posses

sion of that sum. It prevents thousands of wage earners

each year from receiving the fair play to which our legal

system entitles them. Petitioner submits that this Court

should grant the writ in order to apply the requirements

of the Due Process Clause to the process of pre-judgment

garnishment as it operates in Wisconsin.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, petitioners pray that the petition for writ

of certiorari be granted and the judgment below reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

L eroy D. Clark

Gabrielle A. K irk

P hilip G. S chrag

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

T homas M. Jacobson

110 East Wisconsin Avenue

Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53202

Attorneys for Petitioner

W illiam F . Y oung, J r .

Of Counsel

A P P E N D I C E S

la

APPENDIX A

Order to Show Cause

(Formal Parts Omitted)

Upon the Affidavit hereto annexed and upon all the

records, files and proceedings had and on motion of

Barbee & Jacobson, defendant’s attorneys;

I t is ordered, that the above named plaintiff, Family

Finance Corporation of Bay View appear before the

Honorable Thaddeus J. Pruss, County Judge in and for

Milwaukee County, Room 403, in the Courthouse, at 901

North 9th Street, City of Milwaukee, County of Milwaukee,

State of Wisconsin, on the 3rd day of January, 1967, at

9:00 o’clock A.M. or as soon thereafter as counsel can be

heard to show cause why the garnishment proceedings in

the above matter should not be dismissed on the merits

for violating defendant’s rights under the Wisconsin Con

stitution, Article 1, Section 9; and further defendant’s due

process and equal protection rights under the United

States Constitution 14th Amendment.

I t is further ordered, that a copy of this Order to Show

Cause, together with a copy of the Affidavit hereto an

nexed, be served upon the above named plaintiff at least

48 hours prior to the time set for hearing herein.

Dated at Milwaukee, Wisconsin, this 23rd day of Decem

ber, 1966.

/ s / T. J. P russ

County Judge

2a

Affidavit of Thomas M. Jacobson

State of W isconsin,

County of M ilwaukee, ss. :

T homas M. Jacobson, being first duly sworn on oath

deposes and says:

1. That on the 21st day of November, 1966 the plaintiff

commenced an original action and garnishment proceed

ings against the defendant herein;

2. That plaintiff as a result of said garnishment action

against defendant is responsible for the garnishee defen

dant in said matter holding $31.59 due defendant for

wages;

3. That plaintiff has not legally established that defen

dant in fact owes plaintiff any amount of money nor re

duced said claim to a valid judgment.

That the defendant’s attorney makes this affidavit for

the purpose of obtaining an Order directing the plaintiff

to show cause why the garnishment action in the instant

proceedings should not be dismissed for being in viola

tion of defendant’s constitutional rights under the Wiscon

sin Constitution, Article 1, Section 9 and the United States

Constitution, 14th Amendment in that defendant is being

deprived of her property without due process of law and

further Wisconsin Statutes Chapter 267 permitting gar

nishment before judgment of a wage earner’s salary treats

said class unequally in comparison to other individuals

similarly situated; that for said reason your Affiant asks

the Court to declare Wisconsin’s garnishment law before

judgment, more particularly Sections 267.02 (1) (a) 1.,

267.05 (1), and 267.07 (1) Wis. Stats. 1965 unconstitu

tional for the aforesaid reasons.

/ s / T homas M. Jacobson

T homas M. Jacobson

3a

(Formal Parts Omitted)

W herefore an Order to Show Cause returnable before

the Honorable Tbaddeus J. Pruss of the County Court

requiring the plaintiff to show cause why the garnishment

proceedings in the above matter should not be dismissed

on the merits for violating the defendant’s rights under

the Wisconsin Constitution, Article 1, Section 9 and fur

ther defendant’s due process and equal protection rights

under the United States Constitution 14th Amendment

was signed by the Honorable Tbaddeus J. Pruss Decem

ber 23, 1966;

W herefore Affidavit of defendant’s counsel attached

thereto indicated plaintiff commenced an original action

and garnishment proceeding against defendant herein and

pursuant thereto the garnishee defendant held $31.59 due

defendant for wages;

W herefore Affidavit of defendant’s counsel attached

thereto further indicated plaintiff had not legally estab

lished that defendant in fact owed plaintiff any amount of

money nor reduced said claim to a valid judgment there

fore defendant attorney’s affidavit requested the Court to

Order the plaintiff to show cause why the garnishment ac

tion in the instant proceedings should not be dismissed

for being in violation of defendant’s constitutional rights

under the Wisconsin Constitution, Article 1, Section 9 and

the United States Constitution, 14th Amendment in that

defendant is being deprived of her property without due

process of law and further Wisconsin’s Statutes Chapter

267 permitting garnishment before judgment of a wage

earner’s salary treats said class unequally in comparison

to other individuals similarly situated; that for said reason

your Affiant asks the Court to declare Wisconsin’s garnish

ment law before judgment, more particularly Sections

Order of County Court

4a

267.02 (1) (a) 1., 267.05 (1), and 267.07 (1) Wis. Stats.

1965 unconstitutional, for the aforesaid reasons;

W herefore a hearing was held pursuant to the Order

to Show Cause before the Honorable Thaddeus J. Pruss,

January 3, 1967 at 9:00 A. M. in his Courtroom in the

Courthouse at Milwaukee, Wisconsin;

W herefore at said hearing the plaintiff appeared by

counsel Sheldon D. Frank and defendant appeared by coun

sel Thomas M. Jacobson;

Upon all the records, pleadings, and files herein it is

Now THEREFORE ORDERED:

That the garnishment action in the instant proceedings

does not violate defendant’s constitutional rights under the

Wisconsin Constitution, Article 1, Section 9 and the United

States Constitution 14th Amendment due process and equal

protection;

That the said determination is for the legislature and

not for the Court;

That Wisconsin’s garnishment law before judgment,

more particularly Sections 267.02 (1) (a) 1., 267.05 (1),

and 267.07 (1) Wis. Stats. 1965 is therefore not unconsti

tutional.

That defendant’s attorney requests a stay in the garnish

ment action for purposes of appeal therefore the Court

further Orders that all proceedings in the instant garnish

ment action be and hereby are temporarily stayed until

further Order of this Court.

Dated at Milwaukee, Wisconsin, this 7th day of January,

1967.

/ s / T haddeus J. Pruss

T haddeus J. Pruss, County Judge

O r d e r o f C o u n ty C o u r t

5a

(Formal Parts Omitted)

P lease take notice that the defendant, Christine Snia-

dach, does hereby appeal to the Circuit Court of Milwaukee

County, State of Wisconsin from the order made herein

on the 6th day of January, 1967, by the Honorable Thad-

deus J. Pruss, County Court Judge, which Order refused

to dismiss the garnishment action herein on the basis the

Wisconsin garnishment before judgment laws; to-wit, Sec

tions 267.02 (1) (a) 1., 267.05 (1), and 267.07 (1) Wis.

Stats. 1965 did not deprive defendant of her constitutional

rights under the Wisconsin Constitution, Article 1, Section

9, and the United States Constitution 14th Amendment due

process and equal protection.

Dated at Milwaukee, Wisconsin this 9th day of January,

1967.

Notice of Appeal to Circuit Court

/ s / T homas M. Jacobson

B arbee & Jacobson

M artin R. S tein

Defendant’s Attorneys

6a

The appeal in this action having been brought before the

Honorable George D. Young, Judge of the Circuit Court in

and for Milwaukee County, and pursuant to Stipulation of

the parties, judgment rendered after filing of briefs by

both parties,

Now therefore, upon motion of Sheldon D. Frank, attor

ney for the respondent, Family Finance Corporation of

Bay View,

It is hereby ordered :

That the judgment of the Honorable Thaddeus J. Pruss,

Judge of the County Court, in favor of said respondent,

Family Finance Corporation of Bay View and against the

appellant, Christine Sniadach, alias, as rendered and en

tered on the 3rd day of January, 1967, holding that said

action, a garnishment issued before the suit was instituted

was constitutional and did not violate the due process and

equal protection right of the appellant-defendant, be and

same hereby is affirmed.

Dated at Milwaukee, Wisconsin, this 18th day of April,

1967.

Order of Circuit Court

(Formal Parts Omitted)

/ s / George D. Y oung

Judge of the Circuit Court

Approved this 4th day of April, 1967

/ s / T homas M. Jacobson

T homas M. Jacobson, Attorney for Def.

7a

Please take notice that the defendant-appellant, Chris

tine Sniadach, does hereby appeal to the Supreme Court

of the State of Wisconsin from the Order entered herein on

the 18th day of April, 1967 by the Honorable George D.

Young, Circuit Court Judge In and For Milwaukee County

Branch Number One thereof, which Order affirmed the

judgment of the Honorable Thaddeus J. Pruss, County

Judge In and For Milwaukee County, Branch Number Six

thereof, said judgment holding Wisconsin’s garnishment

before judgment statutes constitutional and not in viola

tion of defendant-appellant’s equal protection and due

process guarantees.

Dated this 18th day of April, 1967.

/ s / T homas M. Jacobson

T homas M. J acobson

Defendant-Appellant’s Attorney

To: S heldon D. F rank, E sq., Plaintiff’s Attorney,

135 West Wells Street,

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Clerk op Circuit Court, Milwaukee

County, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Notice of Appeal to Supreme Court

(Formal Parts Omitted)

8a

Prefatory

This is an appeal from Branch 6 of the County Court of

Milwaukee County. The plaintiff above named commenced

a garnishment action against the defendant and named the

Miller Harris Instrument Co. garnishee. Thereafter, the

defendant moved the Court below by way of an order to

show cause requesting the dismissal of the action upon the

ground that the proceeding violated the defendant’s rights

under Article I, Section 9, of the Wisconsin Constitution

and the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution.

The defendant appears now to have abandoned her con

tention that there has been a violation of Article I, Section

9, of the Wisconsin Constitution and now contends that the

proceeding has violated her rights under Article VII, Sec

tion 2, of the Wisconsin Constitution.

M emorandum Decision

I

A rticle VII, Section 2, of the

W isconsin Constitution

Section 2 of Article VII provides in part that “ The judi

cial power of this state, both as to matters of law and

equity, shall be vested in a supreme court, circuit courts,

courts of probate, . . .”

The basis for this argument is that Chapter 267 contains

a presumption made by the legislature that in all disputes

between a creditor and his alleged debtor the creditor will

prevail and the debtor must automatically prepare for sat

Memorandum Decision of Circuit Court

(Formal Parts Omitted)

9a

isfaction of the creditor’s claim through immediate seizure

of his property. It is argued that the plaintiff need only

file the summons and complaint with the clerk who is then

automatically required to issue what purports to be “an

order of the County Court,” although it commands not

merely an appearance but disposes of the property, and

that no judge is involved in any way in this process up

to this point. This argument concludes that all authority

to act in a preliminary dispute involving particular liti

gants has been withdrawn from the Court and is in effect

decided by the legislature.

The foregoing argument does violence to the provisions

of Chapter 267, Wis. Stats. It is true that the legislature

has afforded a remedy not known to the common law for

the protection of creditors. The remedy provided simply

requires that the garnishee complaint must allege the exist

ence of one of the grounds for garnishment, the amount of

the plaintiff’s claim, above all offsets, known to the plain

tiff, and that the plaintiff believes the garnishee is indebted

to or has property in his possession or under his control

belonging to the defendant and that such indebtedness or

property is not exempt from execution (Sec. 267.05 (1)).

Chapter 267 further provides that the garnishee sum

mons and complaint shall be served on the principal defen

dant not later than 10 days after service on the garnishee

as provided in Sec. 262.06 (Sec. 267.07). I f the answer of

the garnishee shows a debt due the defendant, the garnishee

may pay the same or sufficient thereof to cover the claim

of the plaintiff, with interest and costs, to the clerk of the

court. There is the further provision that the plaintiff

may request the garnishee in writing to pay such sum to

the clerk, and the garnishee must, within 5 days after re

ceipt of such request, pay the sum to the clerk who then

M e m o r a n d u m D e c is io n o f C ir c u it C o u r t

10a

issues his receipt to the garnishee who is thereby released

of all liability (Sec. 267.13). However, no trial is had in

the garnishment action until the plaintiff has judgment in

the principal action, which is dismissed in those cases in

which judgment goes for the defendant (Sec. 267.16).

Wisconsin has held that garnishment before execution

is a provisional remedy. Mahrle v. Engle, 261 Wis. 485.

The Court is unable to find Wisconsin authority that di

rectly rebuts the defendant’s attack on Chapter 267 of the

statutes, but it has long been held that a state may by

appropriate legislation authorize the attachment or gar

nishment of property within its borders, subject to the lim

itations of the federal and state constitutions. An attach

ment or garnishment is not a deprivation of property

without due process of law within the meaning of constitu

tional provisions, inasmuch as there must be an adjudica

tion of the rights of the parties before the property can

be subjected to the plaintiff’s claim. Sec. 267.16 (1) does

that very thing.

So far as the payment into court is concerned, no judicial

process seems to be involved. The payment amounts to

nothing more than a ministerial act to relieve the garnishee

defendant of litigation and the funds come into the posses

sion of the court in custodia legis, and until adjudication

in the main action has occurred nothing more than a tem

porary deprivation has occurred. That deprivation is of

statutory creation in favor of the creditor which was in

existence at the time the debt was created. In this con

nection the language of Byrd v. Rector, 112 W.Va. 192,

81 A.L.R. 1213, 1216, is particularly appropriate:

“We think the answer to these propositions is that

a defendant is not deprived of his property by reason

M e m o r a n d u m D e c is io n o f C ir c u it C o u r t

11a

of the levy of a copy of the attachment upon a person

who is indebted to him or who has effects in his cus

tody belonging to the defendant. The most that such

procedure does is to deprive defendant of the posses

sion of his property temporarily by establishing a lien

thereon. Whether the defendant shall be deprived of

such property must depend of course upon the plain

tiff’s subsequent ability to obtain a judgment in per

sonam or in rem on his claim against the defendant.

If, after having full opportunity to be heard in defense

of such claim, a judgment is rendered thereon against

the defendant or his property, there has been no lack

of due process. In the meantime there has been no

deprivation of property. The attachment, quasi rem

in nature, has operated only to detain the property

temporarily, to await final judgment on the merits of

plaintiff’s claim. No constitutional right is impaired.

Mclnnes v. McKay, 127 Me. 110, 141 A. 699. Until such

judgment is obtained, the defendant’s property in the

hands of a garnishee is immune from the plaintiff’s

grasp.”

The Court does not believe there is any need for a judi

cial act until the defendant’s liability to the plaintiff is

before the Court.

M e m o r a n d u m D e c is io n o f C ir c u it C o u r t

II

D eprivation of P roperty Prior to N otice

Defendant argues that her property can be taken before

she receives notice of the garnishment proceeding. This,

of course, is based on the provisions set forth in Sec.

267.07 (1) which provide for service of a copy of the gar

12a

nishee summons and complaint or a notice of such service

be served not later than 10 days after service on the gar

nishee. It is argued that the garnishee defendant cannot

only withhold defendant’s wages but can file an answer

asserting that he owes wages to the defendant and simul

taneously pay a substantial portion of those wages to the

clerk before any notice of the proceeding is given to the

defendant. The argument concludes by stating that the de

fendant is given inadequate notice because such notice as

he gets comes after the purpose of the garnishment is a

fully accomplished fact. This is an erroneous view of the

process.

The timeliness of the notice is truly the basis of the de

fendant’s lament. The important fact, however, is that the

defendant does have notice even though it may be given

after his property is in custodia legis. Defendant’s argu

ment rejects the fact that nothing has happened to the

defendant’s title except it is temporarily in suspension

pending a final adjudication on the debt owed the plaintiff.

The argument would deprive the garnishee defendant of

a means whereby involvement in litigation might be termi

nated in order that a defendant who contracted a debt with

the provisional remedy in existence may have the use of

his property.

Whether a debtor should be relieved of garnishment

while an action for debt is pending is one involving legis

lative or public policy. When the legislative purpose has

been declared in unmistakable language, it is not within

the province of the Court to interpose contrary views of

what the public need demands. Want v. Pierce, 191 Wis.

202. And the courts have nothing to do with the policy of

laws, their only duty is to interpret the laws as enacted

M e m o r a n d u m D e c is io n o f C ir c u it C o u r t

13a

by the legislature. Waldum v. Lake Superior T. & T. R.

Co., 169 Wis. 137.

M e m o r a n d u m D e c is io n o f C irc u it C o u r t

m

No H earing B efore D eprivation of P roperty

The thrust of the defendant’s argument on this point is

that she is not afforded the right to challenge the with

holding of her wages prior to judgment in the main action

and that she loses her property solely upon the service of

summons and verified complaint in the garnishment action.

This argument amounts to a paraphrasing of the second

argument. Since the provisional remedy is constitutionally

allowable a legitimate basis for garnishment exists. The

argument that defendant is afforded no challenge to the

withholding of her wages is ad hominem. If the main ac

tion falls, so then does the garnishment and no property

belonging to the defendant is lost.

The debt was contracted with the provisional remedy in

existence and became part of the contract. To deprive the

plaintiff of that remedy would be an impairment of contract

and constitutionally bad.

Defendant further argues that the main action involves

a promissory note and since plaintiff’s attorney is not per

sonally privy to all the facts he should not be allowed to

verify the complaint and the plaintiff should be required

to personally verify the complaint. Just how this invades

the defendant’s constitutional rights is not made clear.

Certainly the defendant has adequate statutory remedies,

both investigative and procedural, which furnish an ade

quate basis for the protection of her rights.

14a

IV

V iolation of D ue Process Because L ack of N otice I s N ot

Conditioned O n Need F or S ummary P rocess

Defendant argues that absent a claim that a defendant

is about to leave the employ of the garnishee, or is about

to flee the state entirely, the employee’s wages are a con

tinuing asset against which the plaintiff can proceed even

after judgment; that such an exercise of jurisdiction is

normally authorized only where jurisdiction may not he

established in any other manner or the defendant is taking

steps which may frustrate the plaintiff’s judgment.

It is supposed that garnishment was a legislative incen

tive for the extension of credit. A means whereby a seller

might protect himself against persons not well known to

him. Whatever the purpose, the legislature provided the

remedy, and the defendant contracted her debt with the

right of garnishment on the plaintiff’s side. Defendant’s

argument begs the very reason for the statute. Whether

the reason for the statute still exists or has ceased to exist

is a matter for legislative determination.

V

U nconstitutional I nterference W ith A ppellant’s E ight

To Gainful E mployment— V iolation of the F our

teenth A mendment to the U nited S tates Constitu

tion

Defendant cites Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36

(1873), as authority for the proposition that the right to

pursue a gainful employment unimpeded by arbitrary state

interference is a liberty preserved under the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

M e m o r a n d u m D e c is io n o f C ir c u it C o u r t

15a

Constitution. Defendant goes on to argue that Chapter

267, Wis. Stats., deprives defendant of income earned with

out any demonstration that there is a need for such depri

vation. Further, that persons of low income cannot post

the bond in the amount of one and one-half times the sum

in dispute and that, therefore, this remedy is illusory; that

the deprivation of income is the most direct interference

with the employment relationship, and that garnishment

may cause an employee to be discharged by an employer.

Again, whether a creditor should be deprived of the pro

visional remedy in the case of a poor person is a matter

for legislative determination. As matters now stand, the

remedy does not exist until credit has been extended. If

the remedy is drastic, it behooves the defendant to refrain

from contracting debts beyond her ability to pay. Certainly

this Court is without authority in law to override the leg

islative policy declared in Chapter 267, Wis. Stats. There

is nothing arbitrary about establishing a provisional rem

edy in connection with the process of collecting a debt.

Whether a need for that remedy exists is for the legislature

to determine.

M e m o r a n d u m D e c is io n o f C irc u it C o u r t

VI

Denial of E qual Protection of L aw

Defendant argues that Chapter 267 deprives the defend

ant of equal protection of law' in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution because it

permits illegal discrimination between persons in similar

circumstances. This argument is based upon the proposi

tion that Sec. 267.22, Wis. Stats., permits garnishment of

salaries and wages of public officers and employees after

judgment only.

16a

Chapter 267 does treat public employees different than

members of the public at large as stated by the defendant.

It has been held that this is a proper classification. 4 O.A.G.

783. The Court agrees with that opinion. The continuity

of the public business may very well be the reason why

garnishment may not lie against a public employee until

after judgment. That reason may lend support to the de

fendant’s previous argument concerning interference with

her employment but it does not destroy the reason for the

classification. The validity of differentiating between pub

lic and private employees effectively destroys defendant’s

argument in this respect.

Conclusion

The judgment of the County Court of Milwaukee County

must be affirmed, and plaintiff’s counsel will accordingly

prepare an appropriate order for judgment, submit the

same to counsel for the defendant for approval as to form,

and thereafter offer the same for signing and entry.

Dated at Milwaukee, Wisconsin, this 15th day of March,

1967.

M e m o r a n d u m D e c is io n o f C irc u it C o u r t

By the Court:

/ s / George D. Y oung

Circuit Judge

17a

And afterwards, to-wit on the 8th day of December,

A.D. 1967, the same being the 61st day of said term, the

judgment of this Court was rendered in words and figures

following, that is to say:

Opinion of Supreme Court of Wisconsin

F amily F inance Corp. of B ay V iew ,

Respondent,

—v.—

Christine S niadach, alias,

Appellant,

M iller H arris I nstrument C o.,

Garnishee Defendant.

Opinion by Chief Justice Currie

This cause came on to be heard on appeal from the

judgment of the Circuit Court for Milwaukee County and

was argued by counsel. On consideration whereof, it is

now here ordered and adjudged by this Court, that the

order of the Circuit Court for Milwaukee County herein be,

and the same is hereby affirmed. (Justices Heffernan and

Wilkie dissent. Opinion filed.)

18a

O p in io n o f S u p r e m e C o u r t o f W is c o n s in

No. 64

August Term, 1967

S tatk of W isconsin— In S upreme Court

F amily F inance Corp. of B ay V iew ,

Respondent,

Christine S niadach, alias,

Appellant,

M iller H arris I nstrument C o.,

Garnishee Defendant.

A ppeal from an order of the circut court for Milwaukee

county: George D. Y oung, Circuit Judge. Affirmed.