Illinois v. Wardlow Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

August 9, 1999

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Illinois v. Wardlow Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent, 1999. 57da0bbc-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c4f4e288-ffb5-4eaa-b1bb-7a9767dd6559/illinois-v-wardlow-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

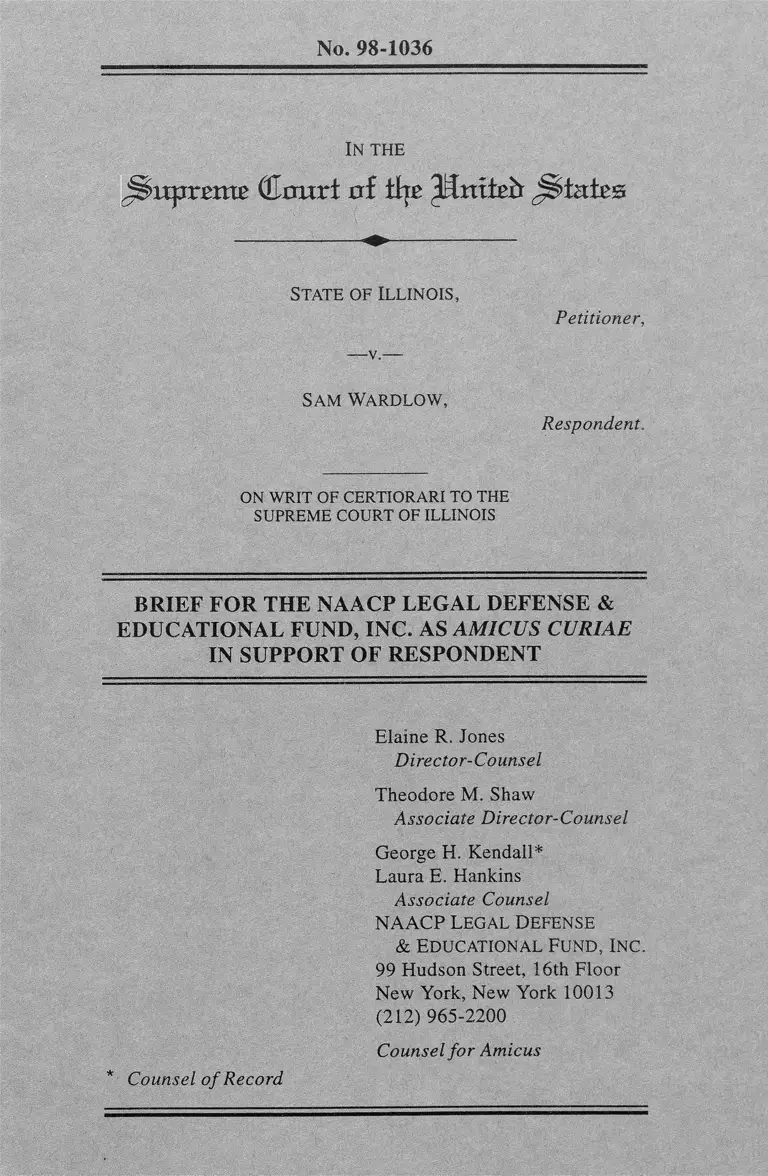

No. 98-1036

IN THE

vcpvetm QJnuri a f t plntieir S ta te s

Sta te o f Il l in o is ,

Petitioner,

SAM WARDLOW,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ILLINOIS

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Associate Director-Counsel

George H. Kendall*

Laura E. Hankins

Associate Counsel

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

& EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Counsel for Amicus

* Counsel o f Record

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities.......................................................................ii

Interest of Amicus Curiae..................................... 1

Summary of Argument..................................................................4

Argument....................................................................................... 5

Without More, Flight From Police Fails to Establish

Likelihood of Criminal Activity....................................5

A. The Terry/Sibron Compromise: Police May

Utilize Stop & Frisk Tactics But Only When

Circumstances Show Ample Factual

Justification That Suggests Criminal Activity

Is A foo t.............................................................. ..5

B. The Currently Troubled State o f Police-

Minority Community Relations Is Highly

Relevant to Understanding Why Citizens Flee

From Police.........................................................8

C. Overwhelming Evidence Shows that Minority

Citizens Fear Law Enforcement Officers

Because o f Systemic Harassment

and Abuse............................................. 9

D. Consideration o f All the Relevant Facts

Requires a Conclusion That Wardlow’s

Flight Is Not Sufficiently Suggestive o f Likely

Imminent Criminal Conduct to Justify a

T erry Seizure................................................ .21

Conclusion............................................. -23

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

PAGE(S)

Adams v. Williams, 407 U.S. 413 (1975)................................... 6

Alabama v. White, 469 U.S. 325 (1990).................................... 7

Batson v. Kentucky, 486 U.S. 79 (1986).................................... 1

Brown v. Texas, 443 U.S. 47 (1979).................................... 7, 21

California v. Hodari D., 499 U.S. 621 (1991)............................ 7

Michigan v. Chesternut, 486 U.S. 567 (1988) ............................ 7

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) .............................. ......1

Nebraska v. Hicks, 488 N.W.2d 359 (Neb. 1992) .....................8

People v. Aldridge, 674 P.2d 240 (Cal. 1984) ........................... 8

People v. Shabaz, 378 N.W.2d 451 (Mich. 1985) .....................8

People v. Wardlow, 678 N.E.2d 65 (111. App. 1997) ..................3

People v. Wardlow, 701 N.E.2d 484 (111. 1998) ......................... 3

Reid v. Georgia, 448 U.S. 438 (1980) ........................................7

Sibron v. New York, 392 U.S. 40 (1968) ......................... 5, 7, 20

State v. Arrington, 582 N.E.2d 649

(Ohio Ct. App. 1990).................................................... -9

ii

Ill

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965).....................................1

Tennessee v. Garner, A ll U.S, 1 (1985)......................................1

Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968)....................................... passim

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970)......................................1

United States v. Cortez, 449 U.S. 411 (1980)...... ........... 6, 9, 21

United States v. Sokolow, 490 U.S. 1 (1989) 6

IV

OTHER AUTHORITIES

ABC World News Tonight with Peter Jennings: Lessons for Kids

on Handling Police (ABC television broadcast,

March 19, 1999) ........................................................... 20

James Baldwin, Fifth Avenue Uptown in NOBODY Knows My

Name: More Notes Of A Native Son (1961) ....... 11

Ann Belser, Suspect Black Men Are Subject to Closer Scrutiny

from Patrolling Police and the Result is More Often

Fear, Antagonism Between Them, PITTSBURGH POST

Gazette, May 5, 1996 ............................................ . 16

Patricia Callahan and Jeffrey A. Roberts, 63% o f Police

Disciplined One in Four Commit Most Violations,

Denver Post, April 27,1997...................................... 14

Leslie Casimir, Minority Men: We Are Frisk Targets,

N.Y. Daily News, March 26,1999 .............................16

David Cole, No Equal Justice (1999) .......................... 20

John J. Farmer, New Jersey State Attorney General,

Final Report Of The State Police Review Team

(July 2, 1999) .................................. ............................. 10

Kevin Flynn, Two Polar Views o f Race at U.S. Hearing,

N.Y. Times, May 27, 1999............. ........... .................. 14

James J. Fyfe, Terry: A[n Ex-]Cops View, 72 St . John's L. Rev.

1231 (1998) ................................................................... 10

Jeffrey Goldberg, The Color o f Suspicion, N.Y. TIMES

Magazine, June 20,1999 ................................ 12, 13

V

Jean Jacovy, Chief’s Move Next on Minorities Board

Recommendations, Omaha World Herald,

September 1, 1998......................................................... 14

Jean Johnson, Americans ’ Views on Crime and Law

Enforcement: Survey Findings, NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF

Justice Journal (September 1997).................................... 15

Holman W. Jenkins Jr., What Happened When NY Got Business

Like About Crime, Wall Street Journal,

April 28, 1999........................ 16

The Law and You: Guidelines for Interacting With Law

Enforcement Officials (produced in partnership by the

NAACP, National Organization of Black Law

Enforcement Executives and Allstate Insurance

Company).............................................. .....20

Minority Troopers Describe A Culture o f Discrimination, N.Y.

Times, July 8,1999.........................................................13

John J. Monahan, Hearings on Alleged Police Abuse Set,

Telegram & Gazette, September 5, 1999................. 14

Plaintiffs’ Fourth Monitoring Report, Pedestrian and Car Stop

Audit, NAACP, Philadelphia Branch and Police Barrio

Relations Project v. City of Philadelphia

No. 96-CV-6045 (E. D. Pa. 1998).... ...................... 18, 19

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and

Administration of Justice, Task Force Report:

The Police (1967)........ 15

Larry Reibstein, NYPD Black and Blue, Newsweek,

June 2, 1997 .... ............................................ . 12

VI

T im Roche and Constance H um burg, Stops Far Too Routine

For Many Blacks, St . PETERSBURG TIMES,

October 3, 1997.... ......................................................... 16

James M. Shannon, Attorney General, Report of the

Attorney General’s Civil Rights Division on

Boston Police Department Practices

(December 18, 1990) ................... ........................... 17, 18

Bruce Shapiro, When Justice Kills, The Nation,

June 9, 1997....... ........................................................... 13

Katherine Shaver, Panel Releases Report on Montgomery

Police, Washington Post, August 26, 1998..............14

Je ro m e Skolnick, Terry and Community Policing, 72 ST. JOHN'S

L. Re v . 1265 (1998)............ .................................. 10, 11

Steven K. Smith et al., Criminal Victimization and

Perceptions of Community Safety in 12 Cities,

1998, (Department of Justice, NCJ 173940,

May 1998) .......................................................... .......... 15

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Racial and

Ethnic Tensions in American Communities:

Poverty, Inequality and Discrimination

(May 1999)............................................................. 13, 19

Peter Veniero, New Jersey State Attorney General,

Interim Report on State Police Practice and

Allegations of Racial Profiling,

April 20, 1999................... ............ .............................. 11

Paul Zielbauer, Racial Profiling Tops NAACP Agenda,

N .Y . T im e s , July 11,1999............... ................. 13

1

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE1

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF) was chartered in

1939 for the purpose of, inter alia, rendering legal services free

of charge to “indigent Negroes suffering injustice on the basis of

race or color.” Its first Director-Counsel was Thurgood

Marshall. See generally NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422

(1963) (describing LDF as a “‘firm’ . . . which has developed a

corporate reputation for expertness in presenting and arguing the

difficult questions of law that frequently arise in civil rights

litigation").

Since its inception, the Legal Defense Fund has sought to

eradicate the race discrimination that has long infected our

Nation’s criminal justice system and has called attention to the

corrosive effects that such bias has on cherished norms of equal

citizenship. Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965); Turner v.

Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970); Batson v. Kentucky, 486 U.S. 79

(1986). Specifically, LDF has participated, as both counsel of

record and amicus curiae, in landmark cases of this Court

announcing the constitutional standards governing police-citizen

encounters. See, e.g, Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968);

Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S 1 (1985). In each, LDF sought to

ensure that the Court’s resolution of the Fourth Amendment

issues presented was informed by a full and realistic

understanding of the costs of unchecked police discretion. Not

only will the harms of unconstitutional police conduct be borne

disproportionately by members of groups historically singled

out for unequal treatment, but such practices are particularly

subversive of the police-citizen trust that is indispensable both

1 This brief was prepared by counsel of record for amicus, with significant

and dedicated assistance from summer intern Kara Finck. No party or

third party made any financial contribution in support of these efforts.

2

to effective law enforcement and to full and equal civic

participation.

These concerns are squarely implicated in this case. At

precisely the juncture that local, State, and federal governments

are beginning to document and come to terms with the

pervasiveness of unjustifiable, race-based police misconduct —

ranging from harassment to use of undue and even lethal force

— the State of Illinois and its various amici insist that the Court

should pronounce flight from the police sufficient in itself to

establish reasonable suspicion as a matter of law. As a matter of

Fourth Amendment doctrine and empirical reality, there can be

no equating the numerous and specific indicia of criminal

activity held sufficient in Terry to overcome the Constitution’s

protections against seizures by the police, and the conduct here,

which is wholly — and regrettably — consistent with what may

be expected of law-abiding individuals in areas where mistrust

and apprehension of the police run high.

The weakening of the Terry standard prayed for by

Petitioners here would deal a serious blow to the efforts of the

Legal Defense Fund and other civil rights organization to

eradicate race-based police practices and to assure that the full

range of constitutional rights are enjoyed no less in our nation’s

inner cities and “high crime” areas than in its “low crime”

enclaves.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In the late morning of Saturday, September 9, 1995, four

cars, each carrying two uniformed police officers, were driving

in tandem through Chicago’s 11th District. The officers were

neither responding to a report or tip of criminal activity, nor

searching for a particular suspect. Officer Timothy Nolan,

riding in the last car, saw Sam Wardlow, a middle-aged African-

American male, standing on the street comer holding a white

3

bag. Officer Nolan did not know Wardlow and testified at the

suppression hearing that Wardlow was not violating any law or

regulation at that time. JA-5. After looking in the police

officer’s direction, Wardlow began to run. JA-6. Officer

Nolan immediately gave chase, during which he failed either to

identify himself or to command Wardlow to stop. Prior to

catching Wardlow, he did not see Wardlow make any effort to

conceal or to hide anything. When he reached Wardlow, Nolan

stopped him and immediately conducted a pat-down search of

his person and bag. Upon feeling the outside of Wardlow’s bag,

Nolan believed it contained a weapon. A search of the bag

revealed a .38 caliber revolver, and Wardlow was placed under

arrest.

The trial court denied the motion to suppress, and after a

stipulated bench trial, found Wardlow guilty of unlawful

possession of a weapon by a felon. Wardlow was sentenced to

two years in the Illinois Department of Corrections. The Illinois

Court of Appeals reversed the conviction, concluding that the

stop and frisk violated this Court's decision in Terry v. Ohio,

392 U.S. 1 (1968). People v. Wardlow, 678 N.E.2d. 65 (111.

App. 1997). That court determined that the ambiguous nature of

flight did not rise to the level of reasonable suspicion required to

justify the officer’s action. Id. at 68. It did not base its decision

on Wardlow’s presence in a high-crime area because it

concluded that the evidence of the location was too vague to

support a determination of a particular and localized high crime

area. Id. at 67. The Illinois Supreme Court affirmed, but on a

different rationale. People v. Wardlow, 701 N.E.2d. 484 (111.

1998). It concluded that flight alone in a high-crime area was

not sufficient to justify a stop and frisk under Terry, not only

because of the ambiguous nature of flight but also because of

an individual’s right to freedom of movement and freedom of

association. Id. at 486-487.

4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In Terry v. Ohio, the Court accepted the argument of our

nation’s police that under appropriate circumstances, stop and frisk

practices were necessary to ferret out crime and could coexist with

the Fourth Amendment, In doing so, however, the Court set a

condition precedent: prior to any such encounter, the police must

possess solid factual justification that the target of the stop and

frisk likely is prepared to engage in criminal behavior. This

condition was established to protect core Fourth Amendment

interests and to prevent groundless harassment of citizens.

As the Illinois Supreme Court recognized, the question this

case presents: whether the mere fact of flight from police —

either alone or in conjunction with a high-crime setting —

would be a close one as a matter of abstract Fourth Amendment

principle. The rights of free association and freedom of

movement protected by the First, Fourth, and Fourteenth

Amendments should not be causally disregarded. But the

Fourth Amendment question this case presents need not — and

should not — be decided as an abstract matter. As documented

herein, the incidence of police harassment, mistreatment, and

even physical abuse of law-abiding minority citizens is

sufficiently high that a desire to avoid police contact is no

longer a reliable indicator that criminality is afoot. Nor should

the fact that flight occurs in a “high-crime” area be used to

change the equation: the documented problems of police abuse

are most serious in precisely those areas where police are most

quick to presume guilt, and the protections of the Fourth

Amendment must not be allowed to mean one thing for the

residents of our inner cities (those who are most vulnerable to

unreasonable and dangerous police conduct) and another for

those who live in our Nation’s “low-crime” enclaves.

Why an inner-city resident flees at the sight of a police officer

is at best ambiguous, and cannot by itself provide sufficient indicia

5

that the citizen is about to commit a crime. Many residents in such

communities, and particularly minority members, have in the past

been harassed by some law enforcement officers and continue to

suffer from such abuse. They possess a legitimate and reasonable

fear of such officials. Indeed, police harassment of law abiding

minority citizens is an acute problem throughout this country.

Unlike prior cases that show police had a credible working

hypothesis that it was likely the suspect was about to commit a

crime, the only factor possessed by police here is Mr. Wardlow's

flight after seeing Officer Nolan. This factor alone, and in

conjunction with the fact that these events took place in an urban

community with a high incidence of crime, fails to satisfies

Terry’s reasonable suspicion test. The judgment of the Illinois

Supreme Court should be affirmed.

ARGUMENT

Without More, Flight From Police Fails To Establish

Likelihood of Criminal Activity.

A. The Terry/Sibron Compromise: Police May Utilize Stop

& Frisk Tactics But Only When Circumstances Show

Ample Factual Justification That Suggests Criminal

Activity Is Afoot.

This Court's decision in Terry’ was a milestone for both the

Fourth Amendment and police-citizen relations. For the first time,

the Court gave its blessing to police-initiated encounters in the

absence of probable cause. The Court concluded that when an

officer possesses objective factors that reasonably suggest a

citizen might well be about to commit a crime, the Fourth

Amendment allows the officer to stop that person briefly, and if

circumstances reasonably suggest the suspect might be armed, to

conduct a brief pat-down search for weapons. Such "legitimate

and restrained conduct undertaken on the basis of ample factual

6

justification" is not "unreasonable" under the Fourth Amendment,

the Court concluded; indeed it exemplifies effective policing. Id.

at 15.

At the same time, the Terry Court fully acknowledged the

weighty constitutional and community security costs that arise

when stop and frisk practices are employed in the absence of such

articulable, objective factors. The Fourth Amendment right to be

free from unreasonable searches and seizures is an "inestimable

right of personal security," Id. at 8-9, and a pat-down search of a

citizen's body "is a serious intrusion upon the sanctity of the

person, which may inflict great indignity and arouse strong

resentment, and it is not to be taken lightly." Id. at 17. "Even a

limited search of the outer clothing for weapons constitutes a

severe, though brief, intrusion upon cherished personal security,

and it must surely be an annoying, frightening and perhaps

humiliating experience." Id. at 24-25.

The Court recognized as well the judiciary’s important role in

securing police compliance with its rule. Because illicit use of stop

and frisk tactics can "only serve to exacerbate police-community

tensions in the crowded centers of our Nation's cities, . . . courts . .

. retain their traditional responsibility to guard against police

conduct which is over-bearing or harassing, or which trenches

upon personal security without the objective evidentiary

justification which the Constitution requires. When such conduct

is identified, it must be condemned by the Judiciary . . . . " Id. at 12,

15 (emphasis added).

In application, the Court has consistently approved

encounters supported by credible indicia of likely criminal activity

and rejected ones that lacked adequate factual support. The Terry

Court found Officer McFadden's confrontation and search of

Terry reasonable because it took place only after attentive study of

what first appeared to be innocent behavior, but as time passed

strongly suggested that Terry and others were preparing to commit

7

armed robbery. Id. at 27-30. Similarly in United States v. Cortez,

449 U.S. 411 (1980), the Court found reasonable a stop of a truck

because border patrol officers had first carefully analyzed a

number of factors that, collectively, firmly suggested the truck

likely contained illegal aliens and their guide. 449 U.S. at 419—

420.2

On the other hand, the Court has not hesitated to reject as

constitutionally impermissible encounters that lack sufficient

indicia of wrongdoing. In Terry's companion case, Sibron v. New

York, 392 U.S. 40 (1968), an eight-hour surveillance yielded only

that Sibron was cavorting with several known drug addicts; the

officer's subsequent search based on this information was firmly

rejected as unreasonable. In Brown v. Texas, 443 U.S. 47 (1979),

the Court determined that a citizen's presence in a high-crime area

and refusal to identify himself to police lacked adequate indicia of

wrongdoing. 443 U.S. at 52. In Reid v. Georgia, 448 U.S. 438

(1980), the Court rejected Reid's traveling with another person but

walking apart from him and occasionally looking back at his

companion, as insufficient suggestion of drug trafficking. 448

U.S. at 441. Thus, unless the circumstances as a whole reasonably

suggest criminal behavior is likely afoot, the Fourth Amendment

2 See also Adams v. Williams, 407 U.S. 413 (1975) (finding reasonable

suspicion supported by the time of day, location of the suspect in a car by

themselves and informant’s tip that the suspect possessed narcotics and a

weapon); United States v. Sokolow, 490 U.S. 1 (1989) (finding police officer

had reasonable suspicion to stop suspect in the airport based on a

combination of over five factors which suggested when taken together that

the suspect was trafficking narcotics); Alabama v. White, 469 U.S. 325

(1990) (finding reasonable suspicion granted to stop an individual based on

an anonymous telephone tip, and subsequent corroboration as a result of

independent police work). See also Michigan v. Chestemut, 486 U.S. 567

(1988) and California v. Hodari D., 499 U.S. 621 (1991) (suggesting that no

Terry violation occurred where police seized fleeing youths after witnessing

youths discard contraband).

protection against government intrusion requires police to refrain

from stop and frisk activities.

B. The Currently Troubled State o f Police-Minority

Community Relations Is Highly Relevant To

Understanding Why Citizens Flee From Police.

Illinois and its amici ask the Court to conclude that the mere

fact of flight from police in a high-crime area is sufficiently

suggestive of likely involvement in imminent criminal conduct

under Terry to justify an otherwise unconstitutional seizure and

search. Illinois argues that while some avoidance behavior, such

as a citizen’s avoiding eye contact with the police, is not

necessarily suggestive of suspicious conduct, "running away from

a clearly identifiable police officer constitutes an innately

suspicious reaction to the presence of police." Illinois Br. at 9. The

United States argues that while flight "may be undertaken for

innocent reasons, it is not behavior in which innocent persons

commonly engage — and it is far more likely to signal a

consciousness of wrongdoing and a fear of apprehension." United

States Br. at 6 (emphasis in original). Several state Attorneys

General assert more boldly that when citizens face unwanted

police attention, the innocent walk way, but the guilty flee. Ohio

et. al. Br. at 5 ("A potential suspect with a guilty conscience may

or may not know the police have independent information tying

her to particular crimes; but when the officer shows up, the citizen

does not want to stay and find out — she runs. On the other hand,

the citizen without the guilty conscience may desire to avoid

interacting with police, so she declines to listen to, or to answer,

police questions and walks on . . . ."). The Criminal Justice Legal

Foundation (herein CJLF) asserts that a per se mle is appropriate

because "flight supports reasonable suspicion because of the close

relationship between flight from authority and a guilty mind."

CJLF Br. at 3.

9

As we show below, these views ask too much. There is good

reason why the majority of courts that have considered the issue

have rejected this position.3 Simply put, the circumstances under

which a citizen will ran from the police are too numerous, and too

often based in innocence, to justify a per se rule 4 At most, it can

be but one factor among many warranting consideration.

Moreover, while Illinois and its amici profess to accept the Terry

principle that reviewing courts must examine the totality of the

circumstances before adjudging an encounter reasonable as a

constitutional matter, see, e.g., Cortez, 449 U.S. at 418, none

discuss or consider a factor that has enormous relevance to

understanding why inner-city African-American residents would

flee from police. That circumstance is fear, the sincere and

understandable response that many inner-city minority residents

— the law-abiding no less than the criminal — to potential

encounters of any type with police.5

C. Overwhelming Evidence Shows That Minority

Citizens Fear Law Enforcement Officers Because

o f Systemic Harassment and Abuse.

3 See, e.g., Nebraska v. Hicks, 488 N.W.2d. 359, 362 (Neb. 1992)

(collecting cases); People v. Shabaz, 378 N.W.2d. 451 (Mich. 1985);

People v. Aldridge, 674 P.2d. 240 (Cal. 1984).

4 See, e.g., Hicks, 488 N.W.2d. at 363 (“fear or dislike of authority,

distaste for police officers based upon past experience, exaggerated fears

of police brutality or harassment and fear of unjust arrest are all legitimate

motivations for avoiding the police.”); State v. Arrington, 582 N.E.2d.

649, 658 (Ohio Ct. App. 1990) (“it is not unreasonable for a young, black

male living in a neighborhood with drag sales and liable to be stopped to

run when approached by a police car...”).

5 The CJLF notes the relevance of this factor, but inexplicably limits it to

"recent immigrants from police states." CJLF Br. at 25. The Americans for

Effective Law Enforcement, Inc., et. al. brief raises generally the subject of

policing minority communities, but does not discuss this issue.

10

There is no question the Terry Court was correct in

recognizing the subversive effect upon both Fourth Amendment

values and constructive law enforcement-community relations that

result when police accost citizens in the absence of reasonable

suspicion of criminal activity. Yet in many minority communities

in contemporary America, youth and adults are to a staggering

degree subjected to stops, frisk, beatings, and in some instances, to

lethal injuries, in the absence of any wrongdoing on their part.

These tragic patterns of pervasive police misconduct have many

harmful consequences, not the least of which is that many

minority citizens — and especially young men in inner cities —

no longer perceive an approaching police officer as a benign force.

To the contrary, bitter experience teaches — and empirical

research confirms — that officers often initiate such encounters in

bad faith, with little regard to these citizens’ basic human

dignity, let alone their constitutional rights.

Police experts understand the effects of unrestrained police

stop and frisk activity upon a subject community. The “real

problem with Terry is that police stop and frisk when it isn’t as

justified as it was in Terry ”6 A highly decorated-former officer

believes unauthorized stops poison police-citizen relations

because “a Terry stop says terrible things about its subject; it is

the officer’s way of telling a person you look wrong and I am

going to check out my feelings about you even if it embarrasses

you.”7 Thus:

[a] citizen’s good or poor opinion may largely be formed

by the impression the citizen has of those fleeting contacts

6 Jerome Skolnick, Terry and Community Policing, 72 St . JOHN’S L. Rev.

1265, 1267 (1998).

7 James J. Fyfe, Terry: A[n Ex-]Cop’s View, 72 St JOHN'S L Rev . 1231,

1243 (1998).

11

with . . . [police]. No other state officials have the

discretionary power, sometimes exercised within seconds,

to consider and apply the law to a citizen, to restrain a

citizen’s liberty by temporary detention, to invade a

citizen’s privacy by search or even to injure or kill a citizen

in self-defense or in protection of others.8

Yet despite the Court’s and law enforcement's understanding

of the corrosive harm that results from illicit and unwanted police-

initiated encounters with citizens, the widespread practice by beat

officers in many urban and minority communities is to defy rather

than to comply with Terry's admonitions. James Baldwin's

haunting declaration from three decades ago — “from the most

circumspect church member to the most shiftless adolescent, who

does not have a long tale to tell of police incompetence, injustice,

or brutality?"9 — sadly is as apt today as when it was first written.

This view is shared not only by police critics but also by some of

the most respected voices in law enforcement.

Charles H. Ramsey, Chief of Police in Washington, D.C.,

noted earlier this year that “despite tremendous gains throughout

this century in civil rights, voting rights, fair employment and

housing, sizeable percentages of Americans today, especially

Americans of color, still view policing in the United States to be

discriminatory, if not by policy and definition, certainly in its day

to day application."10 One major reason for these views is stop and

8 John J. Farmer, New Jersey State Attorney General, Final

Report Of The State Police Review Team 2-3 (July 2,1999).

9 James Baldwin, Fifth Avenue Uptown in Nobody Knows My Name:

More Notes Of A Native Son 62 (1961).

10 Peter Veniero, New Jersey State Attorney General, Interim

Report on State Police Practice and Allegations of Racial

Profiling, April 20, 1999 at 46 (quoting from “Overcoming Fear,

Building Partnerships: Towards a New Paradigm in Police Community

Race Relations” a presentation by Charles H. Ramsey given at the

12

frisk. “Field interrogations that are excessive, that are

discourteous, and that push people around, generate friction.”11

George Kelling, a Rutgers University criminal justice professor

and well known proponent of the “broken windows” theory of

crime control, agrees that stop and frisk practices possess

“tremendous potential for abuse,” and he is deeply critical of

police departments which “indiscriminately stop and frisk

people.”12 Former Officer Fyfe observes that in his experience,

too many officers today are “just making guesses and quite often

they are wrong.”13

One likely explanation for this state of affairs is that a

significant minority of line officers believe that no countervailing

consideration — be it the respect for personal security embodied

in the Fourth Amendment or the equal treatment mandate of the

Fourteenth — should constrain the work of ferreting out crime. A

Baltimore police officer and president of the Baltimore Fraternal

Order of Police openly remarked recently, “of course we do racial

profiling at the train station. If 20 people get off a train and 19 are

white guys in suits and one is a black female, guess who gets

followed? If racial profiling is intuition and experience, I guess

we all racial-profile.”14 Another experienced officer in Southern

California recently confided "racial profiling is a tool we use, and

don't let anyone say otherwise. . . . Like up in the valley, . . . I

Attorney General’s Law Enforcement Summit, in East Rutherford, N.J.

on December 11, 1998.)

11 Skolnick, supra note 6 at 1267.

12 Larry Reibstein, NYPD Black and Blue, NEWSWEEK, June 2, 1997 at

65.

13 Id. at 66.

14 Jeffrey Goldberg, The Color o f Suspicion, N.Y. Times Magazine, June

20, 1999 at 51.

13

know who all the crack sellers were — they look like Hispanics

who should be cutting your lawn."15

Minority police officers who have found the courage to speak

on the record complain that in many departments, a number of

fellow officers routinely harass minority citizens. Gene Jones, a

black police officer in Philadelphia and a staff sergeant in the New

Jersey National Guard told of the lengths that he goes to in order

to avoid traveling on the New Jersey Turnpike so he will not be

stopped by state patrol officers; "Yeah, I go to Jersey for Guard

weekend, I take the back roads. I won’t get on the turnpike. I

won’t mess with those troopers.”16 Several minority New Jersey

State Police officers recently filed suit against that agency,

confirming the prevalence of racial prejudice in its operations.17 In

another instance, a black Philadelphia police officer related that he

was pulled over in a predominantly white suburb, purportedly

because his inspection sticker was placed “abnormally high” on

his windshield.18

Because these aggressive tactics flout the very law the

officers are duty-bound to enforce, police departments throughout

the country are seeing increased numbers of complaints of

arbitrary and unfair street stops, as well as for use of excessive

force,19 and brutality.20 Such large numbers of complaints from

15 Id. at 57.

16 Id. at 60.

17 Minority Troopers Describe A Culture o f Discrimination, N.Y. Times,

July 8,1999 at B2.

18 Goldberg, supra note 14 at 60.

19 In New York, complaints of excessive force have increased 41% since the

police department instituted a zero-tolerance policy. Of those complaints,

75% were filed by African-American and Latino citizens. See Bruce

Shapiro, When Justice Kills, THE NATION, June 9, 1997 at 21.

14

minority community citizens have prompted the NAACP to

announce that ending racial profiling is a top organizational

priority.20 21 22 National and local civil rights commissions are

increasingly called to investigate harassing police practices. In

Omaha, Nebraska, the Human Relations Board recently found that

there was little trust between Omaha police and African-American

citizens, and that many people of color felt mistreated or harassed

by the police because of their race.23 A task force in Montgomery

County, Maryland held similar hearings at which numerous

witnesses recounted having been stopped because they were in

predominantly white neighborhoods.24 In Worcester,

Massachusetts, the local civil rights commission held a series of

hearings at which troubling and substantial allegations of racial

profiling and excessive force were aired.25 In Denver, the local

newspaper listed a string of clear abuses of authority all arising in

20 The Christopher Commission found numerous police radio messages in

Los Angeles which celebrate the use of unnecessary force against citizens:

“make sure you bum him if he’s on felony probation - by the way does he

need any breaking?,” and “Did U arrest the 85 year old lady of [sic] just beat

her up[?]” with the response of “We just slapped her around a bit. . . she/s

getting m/t [medical treatment] now.” UNITED States COMMISSION ON

Civil Rights, Racial and Ethnic Tensions in American Communities:

Poverty, Inequality and Discrimination 25 (May 1999).

21 Paul Zielbauer, Racial Profiling Tops NAACP Agenda, N.Y.TIMES, July

11,1999 at 23.

22 John J. Monahan, Hearings on Alleged Police Abuse Set, TELEGRAM &

Gazette, September 5, 1999 at A3.

23 Jean Jacovy, Chief’s Move Next on Minorities Board

Recommendations, Omaha WORLD Herald, September 1,1998, at 9.

24 Katherine Shaver, Panel Releases Report on Montgomery Police,

Washington Post, August 26, 1998, at B05. The task force also heard

testimony from a parent who reported that his “teenage son had been

followed repeatedly by a police officer who had threatened to kill him if

he did not leave the area.” Id.

25 Monahan, supra note 22 at A3.

15

a single year: “a patrolman is captured on videotape aiming his

gun at a woman in a holding cell; an officer kicks a suspected cop

killer as a TV photographer tapes him; a seven year veteran of the

police force is arrested for allegedly ramming a man with his

police cmiser, then breaking his jaw with three kicks to the

face.”26 In New York City, the United States Civil Rights

Commission recently held hearings on the stop and frisk practice

of the NYPD’s Street Crimes Unit.27

Emerging data reveals that minority citizens are increasingly

unhappy with these aggressive police practices, and that they often

are the targets of distasteful encounters that rarely lead to arrest. In

May of 1999, the Department of Justice released a twelve-city

survey on community perceptions of law enforcement. The survey

found that African-American residents were twice as likely to be

dissatisfied with police practices than were white residents in the

same community.28 These data nearly mirror findings of 30 years

ago.29 A study by the Joint Center for Political and Economic

Studies in April 1996 found that 43% of African Americans

consider “police brutality and harassment of African-Americans a

26 Patricia Callahan and Jeffrey A. Roberts, 63% o f Police Disciplined

One in Four Commit Most Violations, DENVER POST, April 27, 1997, at

A01.

27 Kevin Flynn, Two Polar Views o f Race at U.S. Hearing, N.Y. TIMES, May

27, 1999 § B a t 5.

28 Steven K. Smith et al., Criminal Victimization and Perceptions

of Community Safety in 12 Cities, 1998, (Department of Justice, NCJ

173940, May 1998).

29 President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and

Administration of Justice, Task Force Report: The Police 146

(1967) (finding African-American citizens "significantly more negative in

evaluating police effectiveness in law enforcement").

16

serious problem” in their own community.30 In fact a survey of

polls conducted across the nation and reported in the National

Institute of Justice’s Journal suggests that “many black Americans

are disaffected and suspicious. They are not confident that the

police will be fair. They are not confident that the police will be

professional. They are not confident that the police will ‘protect

and serve.’”31

Available data on stop and frisk practices show these

misgivings to be well-founded. The data show that a large

number of citizens who are stopped and often frisked —

disproportionately members of racial and ethnic minority groups

— were engaged in no criminal conduct. Over a two-year period

starting in 1997, the New York City Police Department Street

Crimes Unit stopped and frisked 45,000 citizens focusing on “high

crime areas.”32 Only twenty percent of the individuals stopped

were arrested. The other 35,500 citizens who lived, worked and

traveled in these neighborhoods were subjected to the “annoying,

frightening and perhaps humiliating experience,” Terry, 392 U.S.

at 25, of police detainment despite being innocent of any of the

wrongdoing of which they were “suspected.” A New York

newspaper survey found that 81 out of 100 randomly questioned

young black and Hispanic men living in New York City had been

stopped and frisked by the police at least once.33 The survey

reported that none of the 81 stops resulted in arrests. In Pittsburgh,

young black males were stopped an average of 3.47 times during a

30 Jean Johnson, Americans’ Views on Crime and Law Enforcement:

Survey Findings, National INSTITUTE OF JUSTICE JOURNAL (September

1997).

31 Id.

32 Holman W. Jenkins Jr., What Happened When N.Y. Got Business Like

About Crime, Wall STREET JOURNAL, April 28, 1999.

33 Leslie Casimir, Minority Men: We Are Frisk Targets, N.Y. DAILY

News, March 26, 1999.

17

five year period compared to white residents who were stopped an

average of 1.53 times during the same period.34 In St. Petersburg,

Florida, a study of police field interrogation reports found that

police conducted street stops of more than 9,000 people over a

period of twenty months, with African-American residents being

stopped entirely out of proportion to their share of the City’s

population. A review of the reasons listed by police officers to

justify the stops included standing by a pay phone, standing

outside a house smoking a cigarette, and riding a bicycle the

wrong way down a one-way street.35

A 1991 report on the Boston Police Department conducted by

the Massachusetts Attorney General concluded that police officers

engaged in improper, and unconstitutional, conduct in the 1989-90

period with respect to stops and searches of minority individuals.36

The report went on to note that:

the most disturbing evidence was that the scope [emphasis in

original] of a number of Terry searches went far beyond

anything authorized by that case and indeed, beyond anything

that we believe would be acceptable under the federal and

state constitutions even where probable cause existed to

conduct a full search incident to an arrest. Forcing young men

to lower their trousers or otherwise searching inside their

underwear, on public streets or in public hallways, is so

34 Arm Belser, Suspect Black Men Are Subject to Closer Scrutiny from

Patrolling Police and the Result is More Often Fear, Antagonism Between

Them, PITTSBURGH POST Gazette, May 5, 1996 at A15.

35 Tim Roche and Constance Humburg, Stops Far Too Routine For Many

Blacks, St. PETERSBURG Times, October 3, 1997 at Al.

36 James M. Shannon, Attorney General, Report of the Attorney

General’s Civil Rights Division on Boston Police Department

Practices 60 (December 18, 1990).

18

demeaning and invasive of fundamental precepts of privacy

that it can only be condemned in the strongest terms.37

This report also documented numerous incidents of police

brutality that occurred during street stops. One sixteen year-old

African-American male reported being stopped, strip-searched

approximately seven times, and forced to lie face down on the

ground. The youth's account, credited by investigators, reported

that “the officers often emerged from the cruisers with guns

drawn, put the guns right to his face, and said that if he moved,

they would shoot him or ‘blow [his] flattop off.”’38 A seventeen

year old black male reported credibly that in 1990 while standing

on a comer, two police officers said “you fucking niggers, get

[out]. We don’t want you hanging on the street anymore.”39 40 The

police officer, after asking the youth what was in his mouth, hit

him and threw him to the ground and then proceeded to conduct a

strip search. Neither youth was arrested, let alone charged with

any crime.

The Massachusetts Report concluded in no uncertain terms

that “the communities hardest hit by crime must not be forced to

accept the harassment of their young people as the price for

aggressive law enforcement. . . . It is hardly an object lesson in

respect for the law and for the police to be searched for no other

reason than that you are young, black and wearing a baseball

In Philadelphia, when race was recorded on the police

department field reports, the overwhelming majority (80.2%) of

stops were of African Americans even though the districts in

37 Id. at 61.

38 Id. at 39.

39 Id at 44.

40 Id at 67.

19

question were racially integrated 41 A review of these reports for

three districts over a week revealed that the police recorded no

explanation in over half of the stops42 None of these stops

resulted in an arrest. Moreover, a number of field reports listed

“stopped for investigation” as the primary reason for making the

stop. Other justifications recorded by police officers included

hanging out on a comer, being homeless, and observing a female

in a known prostitution area.43 In addition to the fact that these

stops were based on wholly innocent activities insufficient to

constitute reasonable suspicion, nearly twice as many minorities

were subject to stops and frisks as compared to white residents.44

Recent studies also show that more often than not, minority

citizens are subject to harsher treatment than whites during these

encounters. The Christopher Commission's examination of police

practices in Los Angeles in the wake of the first Rodney King

verdict documented how minority residents were more likely to be

subjected to excessive force, longer detentions not resulting in a

charge, and to invasive and humiliating police tactics.45

41 Plaintiffs’ Fourth Monitoring Report, Pedestrian and Car Stop Audit at

16, NAACP, Philadelphia Branch and Police Barrio Relations Project v.

City of Philadelphia, No. 96-CV-6045 (E. D. Pa. 1998).

42 Sixty-two percent of the time the police did not record an explanation

for the stop. See id. at 26-27.

43 Id. at 12-13.

44 Id. at 13.

45 The prone-out position is a “police control tactic that requires the suspect

first to kneel, and then he flat on his stomach, with his arms spread out from

his sides or his hands behind his back. The Commission received numerous

accounts of incidents involving African-American and Latino males stopped

for traffic infractions, who were “proned-out under circumstances that did

not present any risk of harm to the officers and that did not involve a felony

warrant.” United States Commission on Civil Rights, supra note 20 at

27 n.l 19.

20

The Commission further determined that when the Los

Angeles Police Department adopted a policing model emphasizing

aggressive street patrol, one result was the alienation of the

majority of law abiding citizens. The report concluded that these

citizens “viewed the police department with mistrust, since they

were perceived by the police as potential criminals.”46 47 In that

same report, a survey of 900 police officers in LAPD found that

one quarter of the respondents felt that “racial bias (prejudice) on

the part of the officers towards minority citizens currently exists

and contributes to a negative interaction between police and

,«47community.

Increasingly, even citizens who were initially supportive of

aggressive stop and frisk efforts in their neighborhoods are

expressing second thoughts. As one Upper Manhattan resident

recently explained, “in the beginning we all wanted the police to

bomb the crack houses. But now it’s backfiring at the cost of the

community. I think the cops have been given free rein to

intimidate people at large.”48

Others — predominantly African-American and Latino

parents — have felt sufficiently fearful of the dangers of contact

with the police that they have enrolled themselves and their

children in seminars that teach how to decrease the likelihood of

harm when encountering the police.49 Moreover, the Allstate

Insurance Company has become so concerned with the state of

police relations with youth that it recently undertook to finance a

46 Id. at 29.

47 Id at 56.

48 David Cole, No Equal Justice 46 (1999).

49 ABC World News Tonight with Peter Jennings: Lessons fo r Kids on

Handling Police (ABC television broadcast, March 19, 1999).

21

joint project with the NAACP to distribute pamphlets to

youngsters on how to act when confronted by a police officer. The

pamphlets, entitled “The Law and You,” instruct teenagers to

“avoid any action or language that might trigger a more volatile

situation, possibly endangering your life or personal well-being.”5

This glimpse of the present status of police-community

relations in many areas of the country is sadly similar to the one

the Terry/Sibron Court confronted and acknowledged three

decades ago.50 51 As it informed the Court’s holding then that stop

and frisk tactics be employed only on the basis of ample factual

justification, the stubborn presence of these very same conditions

today require the Court to consider, as a circumstance of this case,

the fear that minority citizens in inner cities reasonably hold when

they see officers of the law.

D. Consideration o f All the Relevant Facts Requires A

Conclusion That Wardlow's Flight Is Not

Sufficiently Suggestive o f Likely Imminent Criminal

Conduct to Justify a Terry Seizure.

This case contrasts with those in which the Com! has been

w illing to uphold seizures and frisks in the absence of probable

cause, and resembles far more closely the ones in which the Court

has found the factual showing inadequate. Unlike the careful and

deliberate police work described in Terry and Cortez, Officer

50 The Law and You: Guidelines for Interacting With Law Enforcement

Officials (produced in partnership by the NAACP, National Organization

of Black Law Enforcement Executives and Allstate Insurance Company).

51 See Terry, 392 U.S. 1, 14-15 & n. ll (affirming the necessity of the

courts “to guard against police conduct which is overbearing or harassing,

or which trenches upon the personal security without the objective

evidentiary justification which the Constitution requires” and the fact that

stop and frisk can “be a severely exacerbating factor in police community

tensions”).

22

Nolan’s decision to seize and frisk Wardlow was made nearly

instantly, upon Wardlow’s flight, and without the development of

any other fact that might have confirmed the hunch that Wardlow

was about to commit a crime. Indeed, prior to seeing Wardlow,

Nolan had no information of any reported crime in the area, nor

was there any suggestion that Wardlow might be involved in any

criminal activity. In appearance, Wardlow was violating no law.

He was merely standing on the sidewalk, and like many urban

residents, was carrying a bag. And even after he began to run, he

broke no law, nor gave Nolan any further articulable reason to

believe he was committing, or about to commit a crime, or was

armed. At the moment that Nolan seized control of Wardlow and

commenced to pat him down, Nolan possessed no additional

information that suggested that Wardlow was violating any law.

This case is much more like Brown v. Texas in that in both, the

police acted quickly on hunches and failed to develop sufficient

evidence that criminal conduct was afoot prior to the stop.

23

CONCLUSION

The issue that divides us from Illinois is not whether flight

can be considered as a Terry factor, but whether flight alone

satisfies Terry’s “ample factual justification” requirement.

Given the state of police-community relations, flight from police

neither reliably nor sufficiently suggests that criminal activity is

afoot. Because Illinois and its amici have failed to show

otherwise, the Court should affirm the judgement of the Illinois

Supreme Court.

Dated: August 9, 1999 Respectfully Submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Associate Director-Counsel

George H. Kendall*

Laura E. Hankins

Associate Counsel

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

*Counsel of Record

RECORD PRESS, INC,, 157 Chambers Street, N.Y. 10007—96774—(212) 619-4949

www.recordpress.com

http://www.recordpress.com