Plaintiffs' Opposition to Defendants' Application for Stay Pending Appeal

Public Court Documents

March 23, 1977

9 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Plaintiffs' Opposition to Defendants' Application for Stay Pending Appeal, 1977. 5f59e7f1-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c4ffeaad-de85-4c48-807d-03ce905e5d54/plaintiffs-opposition-to-defendants-application-for-stay-pending-appeal. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

V7

5 J

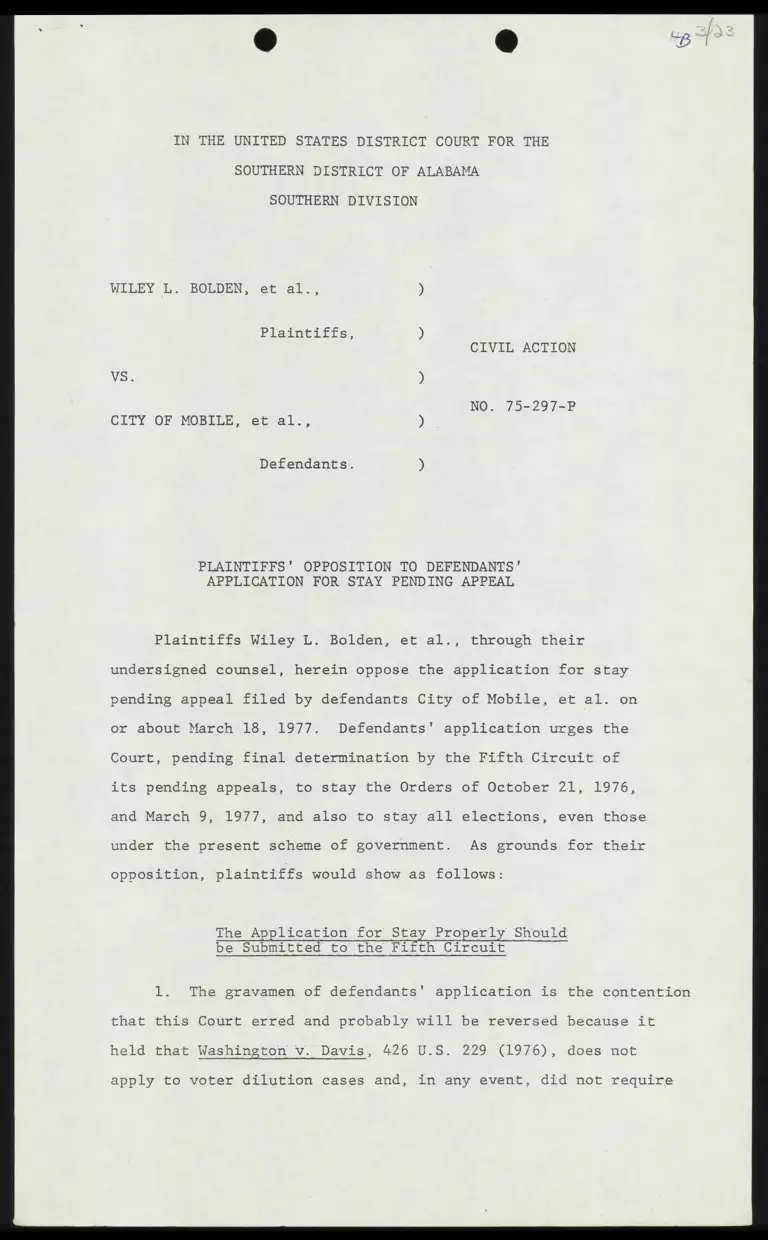

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al., )

Plaintiffs, )

CIVIL ACTION

VS. )

NO. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, et al., )

Defendants. )

PLAINTIFFS' OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANTS’

APPLICATION FOR STAY PENDING APPEAL

Plaintiffs Wiley L. Bolden, et al., through their

undersigned counsel, herein oppose the application for stay

pending appeal filed by defendants City of Mobile, et al. on

or about March 18, 1977. Defendants' application urges the

Court, pending final determination by the Fifth Circuit of

its pending appeals, to stay the Orders of October 21, 1976,

and March 9, 1977, and also to stay all elections, even those

under the present scheme of government. As grounds for their

opposition, plaintiffs would show as follows:

The Application for Stay Properly Should

be Submitted to the Fifth Circuit

1. The gravamen of defendants’ application is the contention

that this Court erred and probably will be reversed because it

held that Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), does not

apply to voter dilution cases and, in any event, did not require

judgment for the defendants in the instant case.

2. But defendants cannot seriously deny that this Court's

are all post-Washington Vv. Davis voter dilution cases from

the Fifth Circuit. They uniformly reject defendants' argument

herein that Washington v. Davis and its progeny have under-

mined the voter dilution standards of Zimmer Vv. McKeithen,

485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)(en banc), aff'd, East Carroll

Parish School Board v. Marshall, 96 5.Ct. 1033 (1978). This

Court's conclusions of law followed the teaching of Paige Vv.

Gray, supra, distinguishing racial gerrymandering cases, which

require proof of racial motivation, from voter dilution

decisions of the Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit, which

should be handled by the multifactor test enunciated in

Zimmer. 538 F.2d at 1110. As this Court noted, 423 F.Supp. at

395 n.10, Paige v. Gray, states in no uncertain terms that

"{tlhe Zimmer standards ... are still controlling in this

circuit." "538 F.2d av 1110 n. 4.

3. In light of the clearly established law in this

circuit rejecting defendants' argument that Washington Vv. Davis

requires in voter dilution cases proof of racial motivation

in the enactment of the electoral scheme, it would be in-

appropriate for this Court to stay its well-reasoned opinion

and injunction when defendants suggest no other ground on

which there is a likelihood of reversal by the Fifth Circuit.

Under these circumstances the Fifth Circuit is the appropriate

court to hear defendants' argument that it should reconsider

its en banc decision in Zimmer or that Zimmer and the other

Fifth Circuit voter dilution cases have been overruled by

Washington v. Davis.

4. For these controlling reasons, defendants' application

for stay pending appeal should be denied. Thereafter, there

is ample time for defendants, if they choose, to press their

application for stay in the Court of Appeals.

5. Alternatively, plaintiffs would not object to the

Court granting a short-term temporary stay of its decrees

just long enough to provide defendants a reasonable

opportunity to have their motion for stay considered by the

Court of Appeals.

6. Although, in light of the settled law in the Fifth

Circuit concerning the standards governing voter dilution

cases the Court need not consider them, plaintiffs will

hereinafter state their additional grounds for opposing the

application for stay.

Other Grounds

7. Defendants have the burden of establishing the

existence of all four (4) factors for the granting of a

stay set out in Pitcher v. laird, 4135. F7.24 743, 744 {5h Clix.

1969), and Belcher v. Birmingham Trust National Bank, 395 F.2d

635, 686 (5th Cir. 1968). Defendants have failed to carry

this burden.

8. There is no likelihood that the defendants-appellants

will prevail on the merits of this appeal. As stated ab ove,

Paige v. Gray, Nevett v. Sides, and McGill v. Gasdsen County

Commission, reject the defendants' constitutional theory.

Nor have defendants alleged in their application there is any

likelihood this Court will be reversed with respect to its

findings of fact. The Fifth Circuit has said it will give

great deference to the district court's determination of

the Zimmer factors. See Paige Vv. Gray, supra, 538 F.2d at

gE

9. By denying the suggestions of defendants herein

and the defendants-appellants in B.U.L.L. ¥. City of Shreveport

Appeal No. 76-3619, the Fifth Circuit has further indicated

its disinclination to reconsider the en banc Zimmer opinion.

10. Contrary to defendants' assertion, Village of Arlington

Heights Vv. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 97 S.Ct.

555, 50 L.Ed.2d 450 (1977), does not extend the scope of

the intent or purpose principles enunciated in Washington Vv.

Davis. If anything, the Supreme Court's discussion of

Washington v. Davis,and Arlington Heights represents yet

another opportunity the Court did not use to extend Washington

v. Davis, to Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971), White

v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973), or their progeny. As this

Court noted in its own opinion, reference to these voter

dilution cases by the Supreme Court is conspicous by its

absence. 423 F.Supp. at 394-95. Even if, arguendo, Washington

v. Davis were applicable to this case, defendants’ application

does not allege that there is a substantial likelihood of

reversal with respect to this Court's finding of "a 'current'’

condition of dilution of the black vote resulting from

intentional state legislative inacrion," by which this Court

reconciled its decision with the principles enunciated in

Washington v. Davis. 423 F.Supp. at 393.

11. Further, defendants' application does not allege

there is a likelihood this Court will be reversed with

respect to its ruling that plaintiffs have stated a cause

of action herein under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

U.S.C. §1973. Even if Washington v. Davis were to apply to

voter dilution cases, and even if the district court erred

in finding legislative intent to discriminate sufficient to

satisfy the standards of Washington v. Davis, plaintiffs are

not required to demonstrate discriminatory intent or motivation

to establish their right to relief under 42 U.S.C. §1973.

12. Contrary to defendants' assertions the Court should

not grant the stay requested on grounds that the appeal

presents ''movel questions.' Certainly the issues on appeal

in the instant case do not approach the degree of novelty

presented by the questions adjudicated in Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533 (1964), wherein the Supreme Court announced

for the first time the substantive rule of one-man-one-vote,

yet refused a petition for stay pending appeal, see 377 U.S.

at 553; or White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973), where the

Supreme Court affirmed for the first time a finding of voter

dilution, yet had denied a petition for stay pending appeal,

405 U.8.: 1201; or Cicy of Richinond v, United States, 95 3.(Ct.

2296 (1975), where, after the Court had denied a stay pending

appeal, 95 S.Ct. at 2300 n.4, it reversed a lower court

ruling that a critical annexation to the City of Richmond

had not unlawfully diluted the voting strength of blacks in

that city.

13. Contrary to defendants' assertion that "this Court

has taken the extraordinary step of proscribing [sic] in

every detail the government that must be used by the City,"

the Order of March 9, 1977, expressly provides that nothing

in it ''shall prevent the defendants or Legislature of Alabama

from changing the powers, duties, responsibilities, or terms

of office of the city council and mayor, or changing the

boundaries of wards or districts, or changing the number of

wards," provided only that such changes comply with the

constitutional principals enunciated by the Court. Indeed,

it is the defendants' refusal to respond to the Court's

repeated invitations to seek to eliminate the racially

discriminatory features of the current election system that

has forced the Court to prescribe an interim form of govern-

ment.

14. In ordering a specific form of government to be

used by the City of Mobile pending affirmative action by

local politicians and the Legislature, the Court has carefully

avoided unnecessary interference with established state

policies. Its mayor-council plan is closely modeled after

plans prescribed by the Legislature for the other large

cities in Alabama. Defendants should be estopped from

attacking the "strong mayor" features of the Court's plan

when at trial they in part based their defense on the

1 undesirability of the ''weak mayor" form provided by the general

Alabama law.

15. Further, defendants should be estopped from attacking

the Court's exercise of its equitable powers, given a finding

of unconstitutional voter dilution, to change the form of

government from a commission to a mayor-council in order to

utilize single-member districts. The inappropriateness of

imposing single-member districts on the commission form of

government was one of the principal elements of the defendants’

defense at the trial of this action.

16. A court-ordered change from one state-approved form

of municipal government to another state-approved form of

municipal government in order to provide a sound constitutional

remedy is no more radical or novel a judicial act than the

redrawing of municipal boundaries. The Supreme Court has made

: i

it absolutely clear that a federal district court must

exercise its equitable powers in this manner whenever it

finds an unconstitutional abridgement of black citizens voting

rights. Gomillion Vv. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960). Indeed,

defendants do not suggest in their application for stay that,

given the finding that the current election system is

unconstitutional, the Court should have adopted a different

remedial plan than the one it has approved.

17. The defendants have not proved or even offered

evidence in an attempt to prove that the City of Mobile will

suffer irreparable injury if the requested stay is not granted.

Indeed, according to newspaper reports the financial expense

of changing to the form of government and election system

prescribed by the Court will cost but a fraction of the amounts

defendants say they plan to spend to attack this Court's

decision. Plaintiffs demand strict proof of defendants' claim

of irreparable injury.

18. Defendants concede the injury that will be done

plaintiffs and the class of black voters they represent in

the event the Court grants the requested stay. Defendants

can only argue that the additional hardship to the plain-

tiff class pales in comparison with the discrimination they

have suffered for the past sixty-six (66) years. But the

Supreme Court has instructed the federal courts to weigh

unconstitutional impairments to fundamental rights of suffrage

with the highest of priorities. The right to an unimpaired,

equal vote is "a fundamental political right, because

preservative of all rights.” Reynolds v. Sims, supra, 377

U.8. at 362, quoting Yick Wo v, Hopkins, 118 U.5. 356, 370.

Plaintiffs' right not to have their voting strength

unconstitutionally diluted far outweighs any administrative

inconvenience or expense the City might incur unnecessarily,

in the event this Court is reversed.

19. Defendants concede that the public interest is

served when its government is elected in a constitutional

fashion. Their only claim that a stay would serve the public

interest is based on the erroneous assertion that the majority

of Mobile's citizens favor the commission form of government

over the form of government and election system adopted by

the Court. In the first place, such an argument, even if

true, is fundamentally unsound: The Constitution of the United

States, which explicitly assigns a higher value to the

unimpaired voting rights of a minority than to the will of

the majority, best expresses the public interest. In any

event, there is no evidence in the record of this case to

show that the majority of Mobile citizens favor a city

commission over a "strong mayor' council form of government.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray, for all the foregoing

reasons, that the Court deny defendants application for a

stay pending determination of an appeal to the Fifth Circuit.

ALTERNATIVELY, plaintiffs pray that the Court grant only

a temporary stay of its Orders for the short time necessary

for defendants to present their petition for a stay to the

Court of Appeals, if they choose.

Respectfully submitted this 23rd day of March, 1977.

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

/

S

R

By: lr 72 " Lr AL

JJ / ~ TBLACKSHER

TARRY MENEFEE

EDWARD STILL, ESQUIRE

601 TITLE BUILDING

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 35203

JACK GREENBERG, ESQUIRE

ERIC SCHNAPPER, ESQUIRE

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE

NEW YORK, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this the 23rd day of March,

1977, I served a copy of the foregoing PLAINTIFFS' OPPOSITION

TO DEFENDANTS' APPLICATION FOR STAY PENDING APPEAL, upon

counsel of record, C. A. Arendall, Esquire, Post Office Box

123, Mobile, Alabama 36601, Fred G. Collins, Esquire, City

Attorney, City Hall, Mobile, Alabama 36602 and Charles S.

Rhyne, Esquire, 400 Hill Building, Washington, D. C. 20005,

by depositing same in United States Mail, postage prepaid

or by HAND DELIVERY.