Brief Amicus Curiae US Dept of Health and Human Services

Public Court Documents

August 1, 1991

70 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Matthews v. Kizer Hardbacks. Brief Amicus Curiae US Dept of Health and Human Services, 1991. 3abf6683-5c40-f011-b4cb-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c522eac7-eb73-48b1-9548-ea719fde27c2/brief-amicus-curiae-us-dept-of-health-and-human-services. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

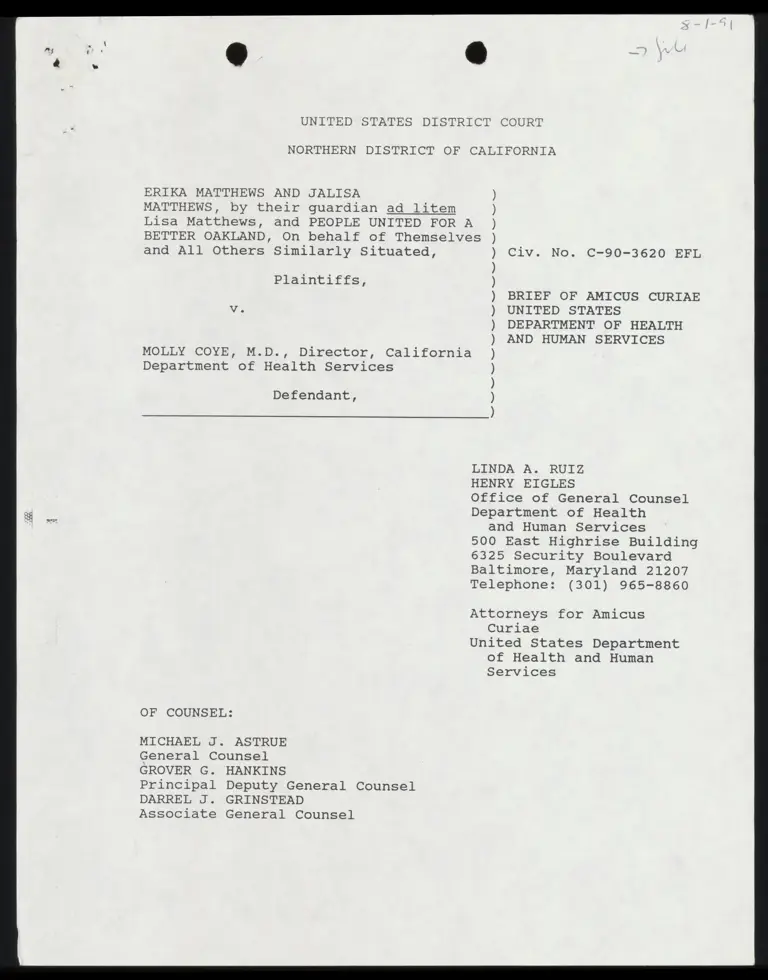

UNITED STATES DISTRI CT “COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

ERIKA MATTHEWS AND JALISA

MATTHEWS, by their guardian ad litem

Lisa Matthews, and PEOPLE UNITED FOR A

BETTER OAKLAND, On behalf of Themselve

and All Others Similarly Situated,

Plaintiffs,

MOLLY COYE, M.D., Director, California

Department of Health Services

Defendant,

S

Civ. No. C-90-3620 EFL

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

AND HUMAN SERVICES

N

t

?

N

a

?

Na

st

?

N

a

a

?

e

n

?

a

?

a

?

N

a

s

?

S

t

?

S

t

?

S

u

l

a

?

s

t

?

u

n

?

S

u

s

”

“

a

n

e

”

OF COUNSEL:

MICHAEL J. ASTRUE

General Counsel

GROVER G. HANKINS

Principal Deputy General Counsel

DARREL J. GRINSTEAD

Associate General Counsel

LINDA A. RUIZ

HENRY EIGLES

Office of General Counsel

Department of Health

and Human Services

500 East Highrise Building

6325 Security Boulevard

Baltimore, Maryland 21207

Telephone: (301) 965-8860

Attorneys for Amicus

Curiae

United States Department

of Health and Human

Services

MICHAEL J. ASTRUE

General Counsel

GROVER M. HANKIN

Principal Deputy General Counsel

DARREL J. GRINSTEAD

Associate General Counsel

LINDA A. RUIZ

HENRY EIGLES

Attorneys

Office of General Counsel

Department of Health and Human Services

500 East Highrise Building

6325 Security Boulevard

Baltimore, Maryland 21207

Telephone: (301) 965-8860

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

United States Department of Health and Human Services

Health Care Financing Administration

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

ERIKA MATTHEWS AND JALISA

MATTHEWS, by their guardian ad litem

Lisa Matthews, and PEOPLE UNITED FOR A

BETTER OAKLAND, On behalf of Themselves

and All Others Similarly Situated,

Civ. No. C-90-3620 EFL

Plaintiffs,

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

AND HUMAN SERVICES

MOLLY COYE, M.D., Director, California

Department of Health Services

Defendant,

N

o

N

t

?

N

e

t

?

N

a

e

?

N

a

f

e

f

N

e

N

f

e

f

a

?

e

l

N

e

N

t

a

’

e

r

INTRODUCTION

This action arises under the Medicaid statute, Title XIX of

the Social Security Act (the Act), and challenges the California

Department of Health Services’ compliance with federal law and

requirements concerning screening and treatment of young

children for lead toxicity under a mandatory part of the

Medicaid program, Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and

A

Treatment (EPSDT). Plaintiffs in this case contend that

federal law requires the California Department of Health

Services to conduct blood lead testing of all Medicaid eligible

children ages 1-5, as part of its EPSDT procedures. The State

maintains that blood lead testing of children ages 1-5 is within

the discretion of the physician. The parties each look to the

State Medicaid Manual, §5123.2D, of the Health Care Financing

Administration (HCFA)' in support of their positions.

The Court issued an order on June 20, 1991 requesting that

HCFA submit an amicus curiae brief addressing the following

questions:

1. On the facts of this case, does the Medicaid Act

require blood lead level testing by the California Department of

Health Services of all children ages one to five eligible under

the Act?

2. On the facts of this case, does the State Medicaid

Manual, §5123.2D indicate that blood lead level testing by the

California Department of Health Services of eligible children

ages one to five is mandatory or discretionary?

This brief is in response to the Court's request.

BACKGROUND

A. The Medicaid Proqran

Title XIX of the Act, commonly known as Medicaid, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1396 et seq., establishes a jointly funded, cooperative

1

The Secretary of Health and Human Services has delegated

the responsibility of administering the federal aspects of the

Medicaid program to the Administrator of the Health Care

Financing Administration.

g

4 §

27

28

federal-state program designed to "enabl[e] each State, as far

as practicable under the conditions in such State," to furnish

medical assistance to eligible individuals. 42 U.S.C. §1396.

See Atkins v. Rivera, 477 U.S. 154, 165, 106 S. Ct. 2456, 2458

(1986) ; Schweiker v. Hogan, 457 U.S. 569, 571 (1982); Harris v.

McRae, 448 U.S. 297, 301 (1980). While the Medicaid program is

voluntary, states which choose to participate must submit a

state plan that fulfills all requirements imposed by the

Medicaid statute and its implementing regulations. 42 U.S.C.

§1396a. See Schweiker v. Gray Panthers, 453 U.S. 34, 36 =-37

(1981); Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. at 301. The Secretary is

obligated to approve a state plan that meets all federal >

requirements. 42 U.S.C. §1396a(b).

Upon approval of the state plan, the state becomes entitled

to reimbursement by the federal government, termed "federal

financial participation" (FFP), for a portion of its payments to

hospitals, nursing homes, and other providers furnishing medical

assistance to eligible recipients. 42 U.S.C. §1396b(a). Both

the state plans and the states’ implementation of the plans are

subject to oversight by the Secretary to ensure continued

compliance with the Federal requirements. 42 U.S.C. § 1396c.

State Medicaid programs are administered by the states, not

by the federal government. Within the broad framework of

federal requirements and oversight, the states operate their

individual programs in accordance with state rules and criteria

that vary widely. "As long as a State complies with the

requirements of the Act, it has wide discretion in administering

3

re

its local program." Lewis v. Hegstrom, 767 F.2d 1371, 1373 (Sth

cir 1985).

The Medicaid statute, however, does mandate that, at a

minimum, states provide certain eligible groups with some

specific services. In addition to those services and eligible

groups mandated by the statute, each ‘state decides for its

program, within the constraints imposed by the statute, the

types and range of services it offers, the payment levels for

services, and the groups eligible in addition to those mandated

by the Act. The states also have considerable discretion

concerning the administrative and operating procedures they will

use to implement Federal requirements, although the Secretary

has imposed some requirements on the $iatas through regulations.

HCFA provides instructional and interpretive guidance to

the states through transmittals, issued as part of the State

Medicaid Manual, about how to comply with federal law.

B. The Early and Periodic Screening,

Diagnostic and Treatment Program

The Medicaid statute mandates that Medicaid recipients

under the age of 21 receive EPSDT services. 42 U.S.C. §§

1396a(a) (43) (A) and 1396d(a) (4) (B). Congress amended the

statute to define EPSDT services when it enacted the Omnibus

Reconciliation Act of 1989 (OBRA 89), Pub. L. 101-239, 103 stat.

2106 (December 19, 1989). Section 6403 of OBRA '89 provided the

28 |

definition of EPSDT services by adding §1396d(r) to the statute,

effective April 1, 1990.°

In particular, §1396d(r) defines screening services to

include, at a minimum,

(1) a comprehensive health and developmental

history (including assessment of both physical

mental health development),

(1i) a comprehensive unclothed physical exam,

(iii) appropriate immunizations according to age

and health history,

(iv) laboratory tests (including lead blood level

assessment appropriate for age and risk factors), and

(v) health education (including anticipatory

guidance).

The Secretary's regulation, promulgated before the 1989

amendment and found at 42 C.F.R. §440.40(b), generally defines

EPSDT services, but does not define the services in detail. The

statutory provision and the regulation are interpreted by the

Secretary in the State Medicaid Manual.

° OBRA 89, §6403, now subsection §1396d(r), was derived

from House Bill H.R. 3299, §4213. Conference Report, H.R. 101~-

386, 101 Cong. 1st Sess., p. 453. The Conference Report stated

that the legislation "codifies the current regulations on

minimum components of EPSDT screening and treatment, with minor

changes," and provides that "screenings must include blood

testing when appropriate, as well as health education."

(Emphasis supplied.) The legislative history furnishes no

additional guidance regarding tests or methods for screening.

5

27

28

C. State Medicaid Manual

In April 1990, following enactment of 42 U.S.C. §1396d(r),

HCFA issued Part 5 of the State Medicaid Manual: Early and

Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT). (Attachment

A hereto.)

At §5110, states are advised, consistent with the statute,

that they must provide for screening, vision, hearing and dental

services at intervals which meet reasonable standards of medical.

and dental practice established after consultation with

recognized medical and dental organizations involved in child

health care. States must also provide for medically necessary

screening, vision, hearing, and dental services regardless of

whether such services coincide with their established

periodicity schedules for these services.

Section 5122 sets out the service requirements for an EPSDT

screening process. The screening process is a medical procedure

to be performed by health professionals (listed with specificity

at §5123.1C), and includes a history of physical and mental

health development, unclothed physical examination,

immunizations, [l]aboratory tests (including lead blood level

assessment appropriate to age and risk), and health education.

Vision, dental, hearing, and other necessary health care

services are included.

Section 5123 discusses screening service delivery and

content and instructs states, at §5123.1, to set standards and

protocols which, at a minimum, meet the standards of 42 U.S.C.

1} §1396d(r) for each component of EPSDT services. The services

“ 2] listed in §5122 are to be part of the screening process.

3 Section 5123.2 sets out the content of screening services

4] to be provided by the states. In particular, at §5123.2D, the

5 Manual addresses laboratory tests that, in the Secretary's view,

6| are appropriate as part of EPSDT screening.

7 D. Appropriate laboratory tests

8 Identify as statewide screening requirements, the

minimum laboratory tests or analyses to be performed

9 by medical providers for particular age or populations

groups. Physicians providing screening/assessment

10 services under the EPSDT program use their medical

Judgment in determining the applicability of the

1 laboratory tests or analyses to be performed. If any

laboratory tests or analyses are medically contra-

12 indicated at the time of the screening/assessment, :

provide them when no longer medically contraindicated.

13 As appropriate, conduct the following laboratory tests.

fi 14 1. Lead toxicity screening

15 Where age and risk factors indicate it is medically

appropriate to perform a blood level assessment, a

16 blood level assessment is mandatory.

17 Screen all Medicaid eligible children ages 1-5 for lead

poisoning. Lead poisoning is defined as an elevated

18 venous blood lead level (i.e., greater than or equal to

25 micrograms per deciliter (ug/dl) with an elevated

19 erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP) level (greater than or

equal to 35 ug/dl of whole blood). In general use the

20 EP test as the primary screening test. Perform venous

blood lead measurements on children with elevated EP

21 ) levels.

22 Children with lead poisoning require diagnosis and

treatment which includes periodic reevaluation and

23 environmental evaluation to identify the sources of

lead.

24

* * *

25

26

27

28 7

DISCUSSION

The provisions of the State Medicaid Manual restate and

interpret the provisions of §1396d(r). States must set

standards and protocols that, at a minimum, meet statutory

requirements. Among other things, states must provide for EPSDT

screening services. The screening process at the outset

includes taking a history of physical and mental health

development, unclothed physical examination, immunizations,

laboratory tests (including lead blood level assessment

appropriate to age and risk), and health education.

As set out above, § 5123.2D recognizes that, under the

EPSDT program, physicians performing screening services are to -

use their medical judgment in determining the applicability of

the laboratory tests or analysis to be performed. A blood lead

level assessment is mandatory where age and risk factors make it

medically appropriate.

The Manual interprets this statutory requirement by

identifying some specific instances where blood lead assessments

are appropriate. With respect to children ages 1-5, the Manual

provides for certain specific screening measures, including lead

toxicity screening.’ The Manual instructs that, in general, the

> As included in the Manual, the Center for Disease

Control (CDC) has defined lead poisoning as an elevated blood

lead level, which is a level greater than or equal to 25

micrograms per deciliter (ug/dl), accompanied by an elevated

erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP) level that is greater than or

equal to 35 ug/dl of whole blood.

8

primary screening test is a test to determine elevated

erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP), which is usually associated

with an elevated blood lead level, referred to as an "EP" test.’

The Manual instructions further provide for venous blood lead

level measurements when elevated EP levels are present.

Thus, the Manual instructs that as part of the medical

screening procedure for children ages 1-5, lead toxicity

screening should be routinely performed via the EP test,

although it may be appropriate not to perform such a test where,

in the physician's "medical judgment," the test is "medically

contraindicated.” That situation should be the exception,

however, rather than the rule, under the Manual's instructions...

The Manual does not provide for venous blood lead level testing

for all children as a screening method, but does instruct that

such testing be done where EP levels are determined to be

elevated.

This Manual instruction is consistent with the Center for

Disease Control's (CDC) Statement on Preventing Lead Poisoning

in Young Children (January, 1985). (Attachment B)> In that

Statement, CDC indicates that "the blood lead levels of U.S.

* The EP test is distinguished from a test for a venous

blood level assessment because an EP test is a test for an

enzyme level that is associated with high blood lead levels. A

venous blood lead level assessment commonly furnishes accurate

results of lead toxicity. (Attachment B, infra, p. 9)

5

CDC personnel have informally advised HCFA that CDC

expects to issue a new Statement in the near future. When CDC

issues its new Statement, HCFA will review its policies

regarding screening procedures by which physicians are to

undertake a blood lead level assessment of Medicaid eligible

children ages 1-5.

children reflect a high degree of environmental contamination by

lead," (Attachment B, p. 9), that lead is most harmful to

children between the ages of 9 months and 6 years, and that,

"ideally, all children in this age group should be screened."

(Attachment B, p. 8) CDC's Statement also recommends that the

"most useful screening tests are those for erythrocyte

protoporphyrin (EP) and blood lead." (Attachment B, P:9). CDC

explained in that Statement that these two tests measure

different aspects of lead toxicity. EP tests measure the level

of EP in the blood, and an elevated level (35 ug/dl or more) may

indicate lead toxicity. Blood lead tests measure lead

absorption, and a confirmed concentration of 25 ug/dl or more

reflects an excessive absorption of lead. (Id.)

CDC further recommended three "feasible" screening

strategies --

1. Screening with EP tests, followed by blood lead

measurements if indicated.

2. Screening with both EP and blood lead tests.

3. Screening with blood lead tests, followed by EP

measurements if indicated.

In particular, CDC recommended EP tests, followed by blood lead

measurements for children with an elevated EP level.

(Attachment B, p. 12)

The State Medicaid Manual instructs states to use, at a

minimum, method 1.

In summary, then, the Manual interprets the statutory

language "appropriate for age and risk factors" to mean that,

with respect to children between the ages of 1-5, the EP test

10

should generally be used as the primary screening device,

followed by venous blood lead assessments where the EP tests

indicate, but acknowledges the physician's discretion not to

perform such tests where medically contraindicated.

OF COUNSEL:

MICHAEL J. ASTRUE

General Counsel

GROVER G. HANKINS

Principal Deputy General Counsel

DARREL J. GRINSTEAD

Associate General Counsel

Respectfully submitted,

2 A

TINTS = RU

HENRY EIGLE

Office of General Counsel

Department of Health

and Human Services

500 East Highrise Building

6325 Security Boulevard

Baltimore, Maryland 21207

Telephone: (301) 965-8860

Attorneys for Amicus

Curiae

United States Department

of Health and Human

Services

1 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

2

I HEREBY CERTIFY that on August 1, 1991, a copy of the

3| Brief of Amicus Curiae, United States Department of Health and

Human Services, in Matthews v. Coye (N.D. Cal., Civ. No. C-90-

4| 3620 EFL), was served by United States mail, postage prepaid, to

the following counsel:

5

JOEL R. REYNOLDS, ESQ.

6 JACQUELINE WARREN, ESQ.

NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL

7 617 S. Olive Street, Suite 1210

Los Angeles, California 90014

8

JANE PERKINS, ESQ.

9 NATIONAL HEALTH LAW PROGRAM

: 2639 S. La Cienega Boulevard

10 Los Angeles, California 90034

11 SUSAN SPELLETICH, ESQ.

KIM CARD. ESQ.

12 LEGAL AID SOCIETY SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA COUNTY

1440 Broadway, Suite 700

13 Oakland, California 94612

rn

i 14 BILL LANN LEE, ESQ.

KEVIN S. REED, ESQ.

15 NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

315 W. 9th Street, Suite 208

16 Los Angeles, California 90015

17 MARK D. ROSENBAUM, ESQ.

ACLU FOUNDATION OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

18 633 South Shatto Place

: Los Angeles, California 90005

: 19

hs EDWARD M. CHEN, ESQ.

20 ACLU FOUNDATION OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

1663 Mission Street, Suite 460

§ 21 San Francisco, California 94103

22 HARLAN E. VAN WYE, ESQ.

DEPUTY ATTORNEY GENERAL, CALIFORNIA

23 2101 Webster Street, 12th Floor

Oakland, California 94612-3049

24

25

26 :

27

28 32

ATTACHMENT A

. EL TE - . . © sami > =

state medicaid manual o2rimenT ol Heaiin NG Human Services Part § — Early and Periodic Screening, nce rnneng Diagnosis, and Treatment

(EPSDT)

Tranamittat No. 3

Date APRIL 1990

REVISED MATERIAL REVISED PAGES REPLACED PAGES

Table of Contents $-1(1p.) S-1(1p.) Sec. 5010 - 5350 5-3 - 3-55(38 pp.) 5-3 - 5-39(37 pp.)

NEW IMPLEMENTING INSTRUCTIONS—EFFECTIVE DATE: APRIL 1, 1990

This transmittal provides guidance on §56403(a), (d) and (e) of OBRA'8S relating to early and periodic screening, diagnostic and treatment services under Medicaid. The cited subsections amended $§1902(a)(43), 1905(aX4XB) and added 2 new §1905(r) to the Act.

The primary purpose of the amendments is to incorporate into the statute existing regulatory requirements found at 42 CFR 440.40(b) and Part 441, Subpart B. However, §6403 does make certain changes as follows:

° modifies the definition of screening services by including appropriate blood lead level testing and health education;

(] requires distinct periodicity schedules for screening, dental, vision and hearing services and requires medically necessary interperiodic screening services;

° adds a new required service component of "other necessary health care, diagnostic, treatment and other measures described in section 1905(a) to correct or ameliorate defects and physical and mental {llnesses and conditions discovered by the screening services, whether or not such services are covered under the State Medicaid plan.”; and

[] clarifies that nothing In the Medicaid law permits limiting EPSDT providers to those which can furnish all required EPSDT diagnostic or treatment services or as preventing qualified providers which ean provide only one such service from program participation.

Changes have been made throughout the manual to accommodate the modifications discussed above,

In addition, §56403(b) and (C) included requirements relating to annual reporting requirements and development of EPSDT participation goals, respectively. This material will be included in a future manual {ssuance.

HCFA-Pub. 45-8

‘

Attachment A

sd ®

»

\

.

CEAPTER V

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING, DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT

(EPSDT) SERVICES

Introduction

ONE Ws tesa resnsncrisnrnsrennrnsnsnrensos ries osinss Los $5010 $3

Program Requirements and Methods

Basie i TOE SS a $110 §S=8

Inforaing Panilies of EPSDT 5429008 srenansssersrsnecne. $121 $=7 EPSDT Service i bbl LT TRIS aaa G dag $122 $9 Screening Service Delivery and CONLONtLsennesretsessnrene $123 $-10 Minimum Standards and RAV PBN S. ss snes tsrnrscensns $123.1 $=10 Screening Service CODLONLInsnsrsnesesnncersarascessiay $123.2 S-11

: Diagnosis and DEGALRANL. cuuansnrsvcertrincescvronronnrn ss $124 €=17 Periodicity i rated 1 Tre aatheia hah hid $140 S-20 Transportation and Scheduling AIBIILANCR cs set rentecccerss $150 $=-23

Utilization of Providers and Coordination with Related Prograzs

Referral for Services Not Covered Under Medicaid.iceeceee. $210 S-25% Utilization of A Lita at PE SE COS $220 $26 Coordination with Related Agencies and PIOR IANS veccereen $230 S-27 Relations With State Maternal and Child Bealth i

PLOGEARS. torerasansrervacevetrvons vovesnererssnss $230.1 S-28 Other Agencies and PIOGIaNS.cetsnersneenesrscecsorvons $230.2 $=-30

F Continuing CAIBessscerrriessrerssntecroneenrnsoncosree ons $240 $=313 {

R pis

Administration

Program Yonitoring, Planning, and BVA luAL iO Mescrnnseceens $310 5-38 Inforaation Needs and ud aah ts TEE Dy VRURLI NE SR Behe $320 S-38 Mainistrative Information Requirements. ceeeececceccns $320.1 5-38 Records or Information on Services and Recipients..... $320.2 S-38 { 180 11m0800000r0u0nsaencnsesncerrvrnersens rion anetynn $330 $=-45 | Re 1EDUPIRMONTcseaannsessetasstsnsrinnscersormrmsnn rss $340 S-51 ro CONIA EAdILY ss suenrssncnssssectenoncnces rene ersnins $350 $=55

Rev. 3

5-1

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING, 04-50 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES $010

4 : Introduction

$010. OVERVIEW

A. Ear]

and Treatment Benefit. —Early ang

periodic screen agnostic and treatment services (EPSDT) is a required service under

the Medicaid program for categorically needy individuals under ge 21. The EPSDT

benefit is optional for the medically needy population. However, if the EPSDT benefit is

elected for the medically needy population, the EPSDT benefit must be made available to

B. A Comprehensive Child Health Program.--The EPSDT program consists of two,

mutually supportive, operational components; : % : :

© assuring the availability and accessibility of required health care resources

\

and

© helping Medicaid reciplents and thelr parents or guardians effectively use

them,

These components enable Medicaid agencies to manage a comprehensive child health

program of prevention and treatm ent, to systematically:

. © Seek out eligibles and inform ‘them of the benefits of prevention and the

health services and assistance available,

© Help them and their familles use health resources, Including thelr own

talents and knowledge, effectively and efficiently,

© Assess the child's health needs through initial and periodic examinations and

evaluation, and

© Asswe that health problems found are diagnosed and treated early, before

they become more complex and their treatment more costly, Although "case

management” does not appear in the statutory provisions pertaining to the EPSDT benefit,

the concept has been recognized as a means of increasing program efficiency and

effectiveness by assuring that needed services are provided timely and efficiently, and

that duplicated and unnecessary services are avoided,

re C. Administration.--You have the flexibility within the Federal statute and

regulations to design an EPSDT Program that meets the health needs of recipients within

your jurisdiction. Title XIX establishes the framework, containing standards and

|_fequirements you must meet,

Rev. 3 : : 5-3

*® EARLY AND PERIODIC SCK.eNING, 0490 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES

Program Requirements and Methods

$110. BASIC REQUIREMENTS

[oBRa 89 amended §51902(aX43) and 1305(aX4XB) and created §$1905(r) of the Social

Security Act (the Act) which set forth the basic requirements for the Program. Under the

EPSDT benefit, you must provide for screening, vision, hearing and dental services at

intervals which meet Feasonable standards of medical and denta) practice established

after consultation with tecognized medical and dents) organizations involved in child

health care. You must also provide for medically Necessary screening, vision, hearing and

dental services regardless of whether such services coincide with Jour established

periodicity schedules for these services, Additionally, the Act requires that any service

which you are permitted to cover under Medicaid that Is necessary to treat or ameliorate

a defect, physical and mental illness, or a condit] n Identified by a screen, must be

provided to EPSDT participants regardless of whether the service or item fis Sitarvis

The statute provides an exception to comparability for EPSDT services, Under this .

exception, the amount, duration and scope of the services provided under the EPSDT

Program are not required to be provided to other program eligibles or outside of the

EPSDT benefit. Services under EPSDT must be sufficient in amount, duration, or scope to

reasonably achieve their purpose. The amount, duration, or scope of EPSDT services to

recipients may not be denied arbitrarily or reduced solely because of the diagnosis, type

of illness, or condition, Appropriate limits may be placed on EPSDT services based on

medical necessity,

. Rev. 3

3-3

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCR_.NING,

0490

DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES $121 $121. INFORMING FAMILIES OF Epspr SERVICES

A. Cenera) Information.—Section 1902(a)43) of the Act requires that the State plan

provide for infor ming all eligible Medicaid recipients under 23 about EPSDT, The intent

of the statute is to allow flexibility of Process as long as the Outcome is effective and is

achieved in o timely manner, generally within 60 days,

: The informing process, which may begin at the intake Interview, extends to no later than

60 days following the date of a family's op individual's initia] eligibility determination, op

of a determination efter a period of ineligibility, A combination of face-to-face, oral,

and written informing activities {s most productive, al

The regulation requires you to assure that your combination of written and oral Inform

methods are effective. Use methods of communication that recipients ean clearly and

easily understand to ensure that they have the information they need to utilize services to

which. they are entitled, HCFA considers "oral" methods to inciude face-to-face

informing by eligibility case workers, health aides and providers as well os public service -

i : It is effective and efficlent to target specific Informing activities to particular "at risk®

groups. For example, mothers with babies to be added to assistance units, familes with

infants, or adolescents, first time eligibles, and those not using the program for- over

2 years might benefit most from oral methods, We nag : B. Individuals to Be Informed.= - - Tare EE

ne ALLA 2°

3

; : Fi

© Inform all Medicald-eligible families about the EPSDT program.

© Inform newly eligible families, either determined eligible tor the first time, for at least 1 year. Use a combination of written and oral methods, generally within

80 days following the date of the eligibility determination, .

Families that go on and off the rolls do not have to be Informed more than once in %

12-month period.

;

© There Is no distinction between title IV-E foster care families and others,

For title IV-E foster care individuals, informing must be with the unit receiving the cash

assistance (e.g., foster parent, administrator of institution), Many title IV-E foster care

individuals are rotated frequently through foster care homes or institutions, and, in some

cases, there are changes in foster parents, institution administrators, or responsible

social workers, It is to the individual's benefit that informing de done initially, not only

with the unit receiving the cash assistance, but with parties who have legal authority over

or custody of the individual

Rev, 3

3

*

$-7

® EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREEN] ’ $121 (Cont.) DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES 04.90

tosm——

Informing about EPSDT encourages appropriate planning for the health ne i When informing foster parents or administrators of 5 Sind i bintadiucg vn foster care individuals in thelr care. Inform institutions or homes having a number of ( individuals annually or more often when the need arises, such as when changes in : administrators, social workers or foster parents ocowr. If an individual is rotated through foster care homes, inform the responsible parties at the homes, unless previously done within the year for other foster care individuals. Annual contact establishes a relationship with the facilities to resolve any problems arising.

o Inform a Medicaid eligible pregnant woman about the availability of EPSDT services for children under age 21 (including children eligible as newborns). A Medicaid eligible woman's positive response to an offer of EPSDT services during her pregnancy, which is medically confirmed, constitutes a request for EPSDT services for the child at birth. For a child eligible at birth (i.e., as a newborn of a woman who is eligible for and receiving Medicaid), the request for EPSDT services is effective with the birth of the child. The parent or guardian of an infant who is not deemed eligible at birth as a [_newborn must be informed at the time the infant's eligibility is determined.

C. Content and Methods.—

© Use clear and nontechnical language, provide a combination of oral and written methods designed to inform all eligible individuals (or their familles) effectively describing what services are available under the EPSDT program; the benefits of preventive health care, where the services are available, how to obtain them; and that necessary transportation and scheduling assistance is available.

Fn Mntorm eligible individuals whether services are provided without cost. States may im y impose premiums for Medicaid on individuals (i.e., pregnant women and infants) whose family income exceeds 150 percent of Federal poverty levels as described In §3571 and, for medically needy participants, may impose enrollment fees, premiums or similar charges [_for participation in the medically needy program.

O

n

© Provide assurance that processes are in place to effectively inform individuals, generally within 60 days of the individual's Medicaid eligibility deter mination and, if no one eligible in the family has utilized EPSDT services, annually thereafter,

o Utilize accepted methods for informing persons who are literate, blind, deaf, or cannot understand the English language. Por assistance in developing appropriate bos procedures, contact agencies with established procedures for working with such individuals, e.g., State or local education departments, employment secwrity offices,

handicapped programs. :

© You have the flexibility to determine how infec mation may be given most

appropriately while assuring that every EPSDT eligible receives the basic information

necessary to gain access to EPSDT services.

$-8 Rev. 3

UNITED STATES DISTRI CT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

ERIKA MATTHEWS AND JALISA

MATTHEWS, by their guardian ad litem

Lisa Matthews, and PEOPLE UNITED FOR A

BETTER OAKLAND, On behalf of Themselve

and All Others Similarly Situated,

Plaintiffs,

MOLLY COYE, M.D., Director, California

Department of Health Services

Defendant,

S

Civ. No. C-90-3620 EFL

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

AND HUMAN SERVICES

N

t

?

N

a

l

N

a

s

t

?

N

a

s

i

?

a

i

N

a

a

e

?

S

i

t

?

a

n

?

a

n

?

S

l

i

?

a

?

a

a

t

’

“

u

n

?

OF COUNSEL:

MICHAEL J. ASTRUE

General Counsel

GROVER G. HANKINS

Principal Deputy General Counsel

DARREL J. GRINSTEAD

Associate General Counsel

LINDA A. RUIZ

HENRY EIGLES

Office of General Counsel

Department of Health

and Human Services

500 East Highrise Building

6325 Security Boulevard

Baltimore, Maryland 21207

Telephone: (301) 965-8860

Attorneys for Amicus

Curiae

United States Department

of Health and Human

Services

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING, 0490 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES 3122

JPA

The EPSDT benefit, in accordance with 51905(r) of the Act, must include the forth below. The frequency with which the services must be provided fs §5140.

EPSDT SERVICE REQUIREMENTS

services set

discussed in

A. Screening Services.—Screening services include all of the following services:

0 A comprehensive health and developmental history (including assessment of both physical and mental health development); ;

© A comprehensive unclothed physical exam;

© Appropriate Im munizations according to age and health history; .

© Laboratory tests (including lead blood jevel ‘assessment appropriate Shes and risk); and ; Ean idly hi |

© Health education (Including anticipatory guidance).

Immunizations which may be appropriate based on age and health history but which are medically contraindicated at the time of the screening may be rescheduled at an

appropriate time.

~ B. Vision Services.—At a minimum, inelude diagnosis and treatment for defects in vision, Including eyeglasses. . 3 CRM

£ C. Dental Services.—At a minimum, fnelude relief of pain and infections, - restoration of teeth and maintenance of dental health, Dental Services may not be limited to emergency services.

° '.

D. Bearing Services.—At a minimum, include diagnosis and treatment for defects in hearing, including hearing aids.

E. Other Necessary Health Care.~Other necessary health care, diagnostic services, treatment and other measwres described in 51905(a) of the Act to correct or ameliorate be defects, and physical and mental [llnesses and conditions discovered by the screening services,

; i PF. Limitation of Services. ~The services available in subsection E are not limited to i those included in your State plan.

© Under subsection E, the services must be "necessary . . . to correct or | ascents defects and physical or mental Qlnesses of conditions . ..." and the defects,

Rev. 3

8-9

yr

® EARLY AND PERIODIC a, : $123 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SEh vICES 01-90

—

Lllnesses and conditions must have been discovered or shown to have increased in severity Dy the screening services. You make the determination as to whether the service is Necessary. You are not required to provide any items or services which you determine are not safe and effective or which are considered experimental.

[= © 42 CFR 440.230 allows you to establish the amount, duration and scope of services provided under the EPSDT benefit, Any limitations imposed must be reasonable and services must be sufficient to achieve their purpose (within the context of serving the needs of individuals under age 21). You may define the service as long as the definition comports with the requirements of the statute in that all services included in §1905(a) of the Act that are medically necessary to ameliorate or correct defects and physical or mental illnesses and conditions discovered by the screening services are provided.

© All services must be provided in accordance with both §1905(a) of the Act - and any State laws of general applicability that govern the provision of health services. Home and community based services which are authorized by §1915(¢c) of the Act are not included among the other health care under subsection E because these services are not included under §1905(a) of the Act.

5123. SCREENING SERVICE DELIVERY AND CONTENT

$123.1 Minimum Standards and Requirements. —

A. State Standards.--Set standards and protocols which, at a minimum, meet the standards of $§1905(r) of the Act for each component of the EPSDT services, and maintain written evidence of them. The standards must provide for services at intervals which meet reasonable standards of medical and dental practice and be established after consultation with recognized medical and dental organizations involved in ehild health care, The standards must also provide for EPSDT services at other intervals, indicated as medically necessary, to determine the existence of certain physical or mental illnesses or conditions. The intervals at which services must be made available are discussed in §5140.

B. Services,—

© Provide an eligidle individual requesting EPSDT services required screening services listed in §5122. This initial examination(s) may be requested at any time, and must be provided without regard to whether the individual's age coincides with the established periodicity schedule. Sound medical practice requires that when children first enter the EPSDT program you encourage and promote that they receive the full panoply 1. screening services available under EPSDT.

© It is desirable that a parent or other responsible adult accompany the child to the examination. When this is not possible or practical, arrange for a followup worker, social worker, health aide, or neighborhood worker to discuss the results in a visit to the home or in contacts with the family elsewhere.

$-10

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREL SG, . DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES $123.2

———

C. Who Screens/Assesses?—

© Examinations are performed by, or under the supervision of, a certified Medicaid physician, dentist, or other provider qualified under State law to furnish primary medical and health services. These services may be provided within State and local health departments, school health programs, programs for children with special health needs Maternity and Infant Care projects, Children and Youth programs, Head Start programs, community health centers, medical/dental schools, prepaid health care plans, a private practitioner and any other licensed practitioners in a variety of arrangements,

© The use of all types of providers Is encouraged. Recipients should have the greatest possible range and freedom of choice. It is required, in the case of title Y, and encouraged, in the case of the primary care projects (I.e., community health centers), that maximum use be made of these providers. Day care centers may provide sites for examination activities. Encourage cooperation when and where other broad-based assessment programs are unavailable, ™ i+. =. ie vz

Fo © Providers may not be limited to those which have an exclusive contract to perform all EPSDT services. Service providers may not be limited to either the private or puble sector or because the provider may not offer all EPSDT services or because it Lofters only one service. Assure maximum utilization of existing resources to more e{fectively administer and deliver services, -

Medicaid providers who offer EPSDT examination services must assure that the services they provide meet the agency's minimum standards for those services In order to be reimbursed at the level established for EPSDT services. - :

To

5123.3 Screening Service Content,— ~~. ‘ton a a

A. Com rehensive Health and Developmental History ‘Information from the parent or other responsible adult who is familiar with the child's history and include an assessment of both physical and mental health development, , Coupled with the | physical examination, this Includes: - hi.” at RT ere a i 2 .

1. Developmental Assessment.—This includes 8 range of activities to determine whether an individual's developmental processes fall within a normal range of achievement according to age group and cultural background, Screening foe developmental assessment is a part of every routine initial and periodic examination,

J

* EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENI.

$123.2(Cont.) DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES 04 4p

Developmental assessment is also carried out by professionals to whom children are referred for structured tests and instruments after potentia] problems have been identified by the screening process. You may build the two aspects into the program so that fewer referrals are made for additional developmental assessment,

a. Approach.—There is no universal list of the dimensions of development for the different age ranges of childhood and adolescence. In younger children, assess at least the following elements: :

© Gross motor development, focusing on strength, balance, locomotion;

© Fine motor development, focusing on eye-hand coordination;

© Communication skills or language development, focusing on expression, comprehension, and speech articulation;

© Self-help and self-care skills;

© Social-emotional development, focusing on the ability to engage in social interaction with other children, adolescents, parents, and other adults; and

© Cognitive skills, focusing on problem solving or reasoning,

As the child grows through school age, focus the program on visual-motor integration, visua)-spacial organization, visual sequential“ memory, attention skills auditory processing skills, and auditory sequential memory. Most school systems provide routines and resources for developmental screening,

For adolescents, the orientation should encompass such areas of special concern as potential presence of learning disabilities, peer relations, psychological/psychiatrie problems, and vocational skills,

b. Procedures.—No list of specified tests and instruments is prescribed for identifying developmental problems because of the large number of such instruments, development of new approaches, the number of children and the complexity of developmental problems which occur, and to avoid any connotation that only certain tests or instruments satisfy Federal requirements. However, the following principles must be consider od:

© Acquire information on the child's usual functioning, as reported by the child, parent, teacher, health professional, or other familiar person.

$-12 : : Rev, 3

o

n

i EARLY AND vesioti Wes ING,

0490 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT LcRVICES

5123.2(Cont.)

© In- screening .for developmental assessment, the examiner incorporates and reviews this information in conjunction with other information gathered during the physical examination and makes an objective professional judgement whether the child is within the expected ranges. Review. developmental progress, not in isolation,

but as 8 component of overall health and well-being, given the child's age and culture,

© Developmental assessment should de culturally sensitive and valid. Potential problems should not be dismissed or excused improperly on grounds of culturally

appropriate behavior, Do not initiate referrals improperly for factors associated with

cultural heritage.

© Programs should not result in a label or premature diagnosis of a

child. Providers should report only that a condition was referred or that a type of diagnostic or treatment service Is needed. Results of {nitial screening should not be

accepted as conclusions and do not represent a diagnosis,

© Refer to appropriate child development resources for additional

assessment, diagnosis, treatment or follow-up when concerns or Questions remain after

the screening process.

2. Assessment of Nutritional Status.—This is accomplished in the base

examination throughs ;

© Questions about dietary practices to identify unusual eating habits (such

as pica or extended use of bottle feedings) or diets which are deficient or excessive in one

or more nutrients.

© A complete physical examination including an oral dental examination.

Pay special attention to such general features as pallor, apathy and Irritability.

© Accurate measurements of height and weight are among the most

important indices of nutritional status,

© A laboratory test to screen for iron deficiency. HCFA and PHS

recommend that the erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP) test be utilized ‘when possible for

children ages 1-5. It is a simple, cost-effective tool for screening for iron deficiency

Where the EP test is not available, use hemoglobin concentration or hematoerit.

oc I feasible, screen children over 1 year of age for serum cholesterol

determination, especially those with a family history of heart disease and/or hypertension

and stroke.

<

Rev, 3 . $-13

3 @® ciriv ano rrrionic scl © 3123.2(Cont.) WIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SER ._ES 05-90

If information suggests dietary inadequacy, obesity or other nutritional problems,

assessment is indicated, including: further

© Family, sociceconomic Of any community factors,

© Determining Quality and Quantity of individual diets (e.g., dietary

intake, food acceptance, meal patterns, methods of food preparation and preservation,

and utilization of food assistance programs), :

© Further physical and laboratory examinations, and

© Preventive, Treatment and follow-up services, including dietary

counseling and nutrition education.

B. Comprehensive Unclothed Physical Examination:~Includes the following:

1. Physical Growth.—Record and compare the child's height and weight with those considered normal Jor that age. (In the first year of life head circumference measurements are important), Use a BTaphic recording sheet to chart height and weight over time.

2. Unclothed Physical Ins ction.—~Check the general appearance of the child to determine overall health status, This process can pick up obvious physical defects, including otthopedie disorders, hernia, skin disease, and genital abnormalities. Physical inspection includes an examination of all organ systems such as pulmonary, cardiae, and gastrointestinal, :

4 Cc, Appropriate Immunizations. —Assess whether the child has been immunized (

against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, measles, Fubella, and mumps, and whether k

booster shots are needed. The child's immunization record should be available to the provider. When an immunization or an updating is medically Recessary and appropriate, provide it and so inform the child's health supervision provider.

Provide immunizations as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and/or local health departments.

D. A iate Laborator Tests.—Identify as statewide screening requirements, the minimum laboratory tests or analyses to be performed by medical providers foe particular age or population goups. Physicians providing screening/assessment services under the EPSDT program use their medical judgement in determining the applicability of the laboratory tests or analyses to be performed. If any laboratory tests or analyses are

fo 1. Lead Toxdeity Screening —Where age and risk factors indicate it is medically appropriate fo perioem a blood level assessment, a blood level assessment is |_mandatory.

$-14

Rev. 3

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING, 07-90 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES '5123.2(Cont.)

I Sergen all Medicaid eligible children ages 1-5 for lead poisoning, Lead poisoning is defined as an elevated venous blood lead level (i.e., greater than or equal to 25 micrograms per deciliter (ug/dl) with an elevated erythrocyte protoporphyrin (CP) level (greater than or equal to 35 ug/dl of whole blood). In general, use the EP test as the primary screening test. Perform venous blood lead measurements on children with elevated EP levels.

Children with lead poisoning require diagnosis and treatment which includes periodic re- evaluation and environmental evaluation to identify the sources of lead. . Co MN Wc ph

8

2. Anemia Test.—~The most easily administered test for anemls” hy: a microhematocrit determination from venous blood or a fingerstick., ii et bo CaS o

N

3. Sickle Cell Test.—Diagnosis for sickle cell trait may be done with sickle cell preparation or 8 hemoglobin solubility test, If a child has been properly tested once for sickle cell disease, the test need not be repeated.

he 4. Tuberculin Test.—Cive a tuberculin test to every child who has not received one within a year,

io

-

x S. Others.—In addition to the tests above, there are several other tests to consider. eir appropriateness are determined by an individuals age, sex, health history, clinical symptoms and exposure to disease, These include a urine screening, pinworm slide, urine culture (for girls), serological test, drug dependency screening, - stool specimen for parasites, ova, blood, and HIV screening. ee

development and to provide information about the benefits of healthy lifestyles and practices as well as accident and disease prevention,

F. Vision and Hearing Screens.—Vision and hearing services are subject to their own periodicity schedules (as described in §5140). However, where the periodicity schedules coincide with the schedule for screening services (defined in §5122 A), you may include vision and hearing screens as a part of the required minimum screening services,

2. Appropriate Hearing Screen.—Administer an age-appropriate hearing assessment. Obtain consultation and suitable procedures for screening and methods of administering them from audiologists, or from State health or education departments.

Rev, 4&

35-15%

i

L

- EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING, :

$123.2(Cont.) DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES i 07-90

. are needed at an earlier age, provide the needed dental services,

G. Dental Screening Services.——Although an oral screening may be part of a physical examination, it does not substitute for examination through direct referral to a dentist. A direct dental referral is required for every child in accordance with your periodicity schedule and at other intervals as medically necessary, Prior to enactment of OBRA 89, HCFA in consultation with the American Dental Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Practice, among other organizations, required direct referral to a dentist beginning at age 3 or an earlier age If determined medically necessary. The law as amended by OBRA 89 requires that dental services (Including initial direct referral to a dentist) conform to your periodicity schedule which must be established after consultation with recognized dental organizations involved In child health care.

~\

© Especially in older children, the periodi~!ty schedule for dental examinations is not governed by the schedule for medical examinations. Dental examinations of older children should occur with greater frequency than is the case with physical examinations, The referral must be for an encounter with a dentist, or a professional dental hygienist under the supervision of a dentist, for diagnosis and treatment. However, where any screening, even as early as the neonatal examination, indicates that dental services

ov"

© The requirement of a direct referral to a dentist can be met in settings other than a dentist's office. The necessary el ment is that the child be examined by a dentist or other dental professional under the supervision of a dentist. In an ares where dentists are scarce or not easy to reach, dental examinations in a clinie or group setting may make the service more appealing to recipients while meeting the dental periodicity schedule. If continuing care providers have dentists on their staff, the direct referral to a dentist requirement is met. Dental paraprofessionals under direct supervision of a dentist may perform routine services when in compliance with State practice acts,

.

© Determine whether the screening provider or the agency does the direct referral to a dentist. You are ultimately responsible for assuring that the direct referral is made and that the child gets to the dentist's office in a timely manner.

5-18

Rev. &

ATTACHMENT B

99-2230

A STATEMENT BY THE

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL

JANUARY 1985

Reprinted July 1985

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL

CENTER FOR ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH

CHRONIC DISEASES DIVISION

ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30333

Attachment B

Use of trade names is for identification only and does not constitute endorsement by the Public

Health Service or by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Preface

This second revision of the Centers for Disease Control's (CDC's) statement, Preventing Lead

Poisoning in Young Children, is more comprehensive than the two previous versions. With help

from members of CDC's Ad Hoc Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention

and other expert consultants, we have considered new research findings on lead toxicity, redefined

lead poisoning at a lower blood lead level, and updated our recommendations on lead-based paint

abatement. In addition, a recent article on a new treatment scheme for lead poisoning (symptomal-

ic and asymptomatic) is included.

The precise threshold for the harmful effects of lead on the central nervous system is nol

known. In the meantime, we have used our best judgment as to what levels of lead are toxic and

whal practical interventions will lower blood lead levels. As public health officials. our duty is to

protect children as best we can—given the limitations of science and the need to make decisions

without perfect data. This is the Department of Health and Human Services’ major policy statement

on the issue.

The progressive removal of lead from leaded gasoline is lowering average blood lead levels in

the United States, but the problem of the major source of high blood lead levels in our.

country—millions of old housing units painted with lead-based paint—is largely unsolved. Until

betler approaches and more resources are available for removing lead paint hazards in older dwell-

ings where children live, lead poisoning will continue to be a public health problem.

The Committee considered a number of controversial issues, and members vigorously debated

until a majority indicated that they could support the point under consideration. Readers should

carefully weigh the recommendations in this document, and they should pay particular attention to

references to work done since the 1978 CDC statement on lead. This 1985 statement represents

agreement of 11 of the 12 Advisory Commitiee members. One member, Dr. Jerome F. Cole of the

International Lead Zinc Research Organization, did not support the recommendations. Minutes of

the Advisory Committee meeting on May 17-18, 1984, and Dr. Cole's statement of dissent are

available upon request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The time, effort, and meticulous care the Committee devoted 10 this statement are gratefully ac-

knowledged. This group of dedicated health professionals, along with notable expert consultants,

labored through the results of several years of research in order to gain consensus on extremely

complex issues. The various drafts of this document had the benefit of thoughtful suggestions from

Committee members and consultants alike. Their work will help protect the children of this nation

from this preventable disease for many years {0 come.

Vernon N. Hoult, M.D.

Director

Center for Environmental Health

iii

Contents

INTRODUCTION or UT Rn I EES CR Be SN CE ER NG Sed Rt Oe IE SN (ER |

pnt Dale DRE See TR ee IRL NRE LE OF Ea CDN ER a SRE ie 1

Il. BAC KG ROUND se oi ss cs sions snr sis tne ats Phin ainnia eines said ide 3

111. SOURCESOF LEAD EXPOSURE a. i. iidbt sdb dd de rei ilg a 5

Lead Based Pali... co, cy ies ss etiens is nas Pe aie aise ae a dG a 5

Xen nh SIE GE Ra eR SN EE ae CC RA IN IY Se Si eC PCC 5

SE SIRE ME PT SS Ra ECORI le i IE Cl IN I NH RR BR 7

DCU DA ON SONI BE. ve tn iri, chaise tines nan ras a eA bad de AE eas a 7

tenn nn 0D UD RE I Te SUTTER JE i ae DOR We i fey hs mg VE a emi

Lead- at PO eRY ro ates sv mirv ne ov vs ales vs ames nd ane te A a a Re 7

OUNCES OUICES oy aes eo aise sioisidis nin ins von Luni rin avin nie sini = sions Hoalnnds aa ia inis sadn Sa LEO 7

IV. SO RE ENING ne et vee sais sd in anni ane natn han ay ay a eae A a 8

GOA Of ChHAhoOD Lead POISORINIE vs. oo Fal sianins ivan sini tn siviain’s aos a Sai ae ve Sl aa 8

Fare POPU ON ey se i al ss ers ie ss st sania cn En susie sins se a nn 8

Screen NE SC NBAUIE I... i ar DU re A ee a i en a i SAE 8

Ue ed MR EE SC ON TW SC IRE RC I I Sr A CNG 9

Tn rn BC BE ERI a RC DA i He RE 1 CR Teg I Be RN al Ce SES Se 9

Measurements Of ErytNIOCYIe ProlOPOTPRYIIY c. lee esis iin stsntns tur ehrsd ene sisnsonssress sete 10

Measurement of Blo Lead. . re. ey cd ee Ci er ne a ie ays ae sea 12

Shona bn TT OEE CR ER Se CIN CI Tl i SE Pa CET AT 12

Interpol aliONIORSCIEBRITIE . otic se viens sinh ioe vs Mis sie vines iv iain nie ns vay vans es Aa en rie anita sin 12

V. DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION i es ts Cah a iofalie ns ES eieiiton + ante wwe vie sine Woabn elaiabe 14

20 en T ETT S TRO) SERNAESICT ra S RE U AON E 14

VI. CLINIC AL MANAGEMENT oo... cn aii ssn can aig vis ane yd sine vie tales ik conde ass ain» wel 16

Hot TL Re IRR TT GE a St SR a SE SEE CITE CE a. 16

LR Em IE Ta EN RR Rg SEY Js SRN BL EE EN AR Co 17

by TL I RT I RE ag RR SS a Pl 0 17

LOW RISK (i. oh ciate sh vinis sine ie sm vols Sin dein hr a ait Be sve te Be is a i a i a ae 17

VII. ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION AND LEAD HAZARD ABATEMENT ...................... 18

Ro Ly EEG ean AT IE CR DE ASE ERE or ENN SI SO 18

Fog on Un ER GR EER UNE VL [A CR SE SS PE ThE NE et 20

IE DL SR LE MR I Ie SL I CR pS CO (ha. I i ae 20

Log SERED ie ar TE NAT RIE Ri NE Sri ENE CVE SE ls Cet NE INE EG a 20

OCCUPA OB os i eis hein wtih Pe aids + is vins larnls 5 wn inain Mies as Ss a hes a aie a a a 20

EDLC Lo Te ee Ne AE EN AT G0 SR IN En EEE Sie Mee CL 21

VI HE AL TH ED IC AT ON ie ns te ssa sn nse mines o Bn viv vin + eu ih vim v ale av ar 22

IX. REPORTING LEAD TOXICITY ANDELEVATED BLOOD LEADLEVELS .....vvovv vin oife ius 22

X. REE RE RENCE i cr ce ere vis Vm ii ssi chat ainiasn ware ain se Sn 4s ala a mien enincainte waa asa nS ay aia 23

APPENDIX — Management of Childhood Lead Poisoning: Special Article ............. 0 iiiiiienninn.. 26

Contents - continued

Figure 1. Sources of Lead in a Child’s Environment ESSN Treen si SB asi tt ss vais enniateieinnints bie wione ee eit ee i

Table 1. Suggested Priority Groups for Lead no Se EEN Pale Cea Le a

Table 2.A Zinc Protoporphyrin (ZnPP) by Hematofluorometer: Risk Classification of

Asymplomatic Children for Priority Medical Evaluation ..................................

Table 2.B Erythrocyte Protoporphyrin (EP) by Extraction: Risk Classification of

Asymptomatic Children for Priority Medical Evaluation SBS eI We v8 9 0 8 ale Sale 00 A008 Sinn we ee eae

Lead is ubiquitous in the human environment as a

result of industrialization. It has no known physiologic

value. Excessive absorption of lead is one of the most

prevalent and preventable childhood health problems in

the United States today. Children are particularly sus-

ceptible to its toxic effect.

Since 1970, the detection and management of children

exposed to lead has changed substantially. Before the

mid-1960’s, a level below 60 micrograms of lead per

deciliter (ug/dl) of whole blood was not considered

dangerous enough to require intervention (Chisolm,

1967). By 1975, the intervention level had declined

50% —t0 30 ug/dl (CDC, 1975). In that year, the Center

{now Centers) for Disease Control (CDC) published /n-

creased Lead Absorption and Lead Poisoning in Young

Children: A Statement by the Center for Disease Conirol.

Since then, new epidemiologic, clinical, and experimental

evidence has indicated that lead is toxic at levels pre-

viously thought to be nontoxic. Furthermore, it is now

generally recognized that lead toxicity is a widespread

problem —one that is neither unique to inner city children

nor limited to one area of the country.

Progress has been made. The Second National Health

and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II) has es-

tablished average blood Jead levels for the U.S. popula-

tion; lead-contaminaled soil and dust have emerged as

important contributors to blood lead levels, as has leaded

gasoline, through its contribution to soil and dust lead

levels. An increasing body of data supports the view that

lead, even at levels previously thought to be “safe,” is

loxic to the developing central nervous system; and

screening programs have shown the extent of lead poison-

ing in target populations.

A major advance in primary prevention is the phased

reduction of lead in gasoline. It is probably responsible

for the findings of reduced average blood lead levels in

children nationwide (Annest et al., 1983) and in (wo

major cities (Rabinowiiz and Needieman, 1982; Billick ei

al., 1980; Kaul et al., 1983). Lead is no longer allowed in

paint to be applied \o residential dwellings, furniture, and

toys. '

The sources of lead are many. They include air, walter,

and food. Despite the 1977 ruling by the Consumer Pro-

duct Safety Commission (CPSC) that limits the lead con-

I. Introduction

tent of newly applied residential paints, millions of hous-

ing units still contain previously applied leaded paints.

Older houses that are dilapidated or that are being

renovated are a particular danger to children. In many

urban areas, lead is found in soil (Mielke ei al., 1983) and

house dust (Charney et al., 1983). Consequently, screen-

ing programs—a form of secondary prevention —are still

needed to minimize the chance of lead poisoning devel-

oping among susceptible young children.

Lead poisoning challenges clinicians, public health au-

thorities, and regulatory agencies to pul into action the

findings from laboratory and field studies that define the

risk for this preventable disease. Although screening pro-

grams have been limited, they have reduced the number

of children with severe lead-related encephalopathy and

other forms of lead poisoning.

The revised recommendations in this 1985 Statement

reflect current knowledge concerning screening, diagno-

sis, treatment, followup, and environmental intervention

for children with elevated blood lead levels. Clearly, the

goal is to remove lead from the environment of children

before it enters their bodies. Until this goal is reached,

screening, diagnosis, treatment, followup, and secondary

environmental management will continue to be essential

public health activities.

DEFINITIONS

The two terms defined below—elevated blood lead

level and lead toxicity —are for use in classifying children

(whose blood has been tested in screening programs) for

followup and treatment. The terms should not be inter-

preted as implying that a safe level of blood lead has been

established. Furthermore, they are 10 be used as guide-

lines. They may not be precisely applicable in every case.

Each child needs to be evaluated on an individual basis.

The CDC is lowering its definition of an elevated

blood lead level from 30 10 25 ug/dl. The definitions

below are simplified versions of those in Preventing Lead

Poisoning in Young Children: A Siatemeni by ihe Center Jor

Disease Control: April 1978 (CDC, 1978).

® elevated blood lead level, which reflects excessive

absorption of lead, is a confirmed concentration of

lead in whole blood of 25 ug/dl or greater:

® lead toxicity is an elevated blood lead level with an

erythrocyle protoporphyrin (EP)”_level in whole

blood of 35 ug/dl or greater.

As defined by blood lead and EP levels, the terms lead

raxicity and lead poisoning are used synonymously in this

document. “Poisoning” is generally used to describe epi-

sodes of acute, obviously symptomatic iliness. The term

“toxicity” is used more commonly in this document,

since screening programs usually involve asymplomatic

children.

EP results are expressed in equivalents of free erythrocyte protoporphyrin (FEP) extracted b

ed in micrograms per deciliter of whole blood. |

= 9 _ ott oe. dd ene. be SL. x

According to this Statement, the severity of lead toxici-

ty is graded by two distinct scales—one for use in screen-

ing, the other for use in clinical management. In the scale

used in screening, children with lead toxicity are divided

into classes 1, II, 111, and IV (section IV). These classes

indicate the urgency of further diagnostic evaluation (sec-

tion V). After the diagnostic evaluation, they are placed

in one of four risk groups: urgent, high, moderate, and

low (section VI). .

y the ethyl acetate-acetic acid-HCl method and report-

n this Statement, 2in¢ protoporphyrin (ZnPP) and FEP are referred to as EP.

U

F

A nationwide survey, conducted from 1976-1980,

showed that children from all geographic areas and socio-

economic groups are at risk of lead poisoning (Mahaffey,

Annest et al., 1982). Data from that survey indicate that

3.9% of all U.S. children under the age of § years had

blood lead levels of 30 ug/dl or more. Extrapolating this

to the entire population of children in the United States

indicates that an estimated 675,000 children 6 months to

5 years of age had blood lead levels of 30 ug/d! or more.

There was, in addition, a marked racial difference in

those data. Two percent of white children had elevated

blood lead levels, but 12.2% of black children had elevat-

ed levels. Further, among black children living in the

cores of large cities and in families with annual incomes

of less than $6,000, the prevalence of levels of 30 ug/dl

or more was 18.6%. Among white children in lower

income families, the prevalence of elevated lead levels

was eight times that of families with higher incomes.

In the past decade, our knowledge of lead toxicity has

greatly increased. Previously, medical attention focused

on the effects of severe exposure and resultant high body

burdens associated with clinically recognizable signs and

symptoms of toxicity (Perlstein and Attala, 1966; Chi-

solm, 1968; Byers and Lord, 1943). It is now apparent

that lower levels of exposure may cause serious behavior-

al and biochemical changes (De la Burde and Choate,

1972, 1975, NAS, 1976; WHO, 1977). Recent studies

have documented lead-associated reductions in the bio-

synthesis of heme (Piomelli et al., 1982), in concentra-

tions of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D (Rosen et al., 1980;

Mahaffey, Rosen et al., 1982), and in the metabolism of

erythrocyte . pyrimidine (Angle and Mclintire, 1978;

Paglia et al., 1977). Results of a growing number of stud-

ies indicate that chronic exposure to low levels of lead is

associated with altered neurophysiological performance

and that the young child is particularly vulnerable to this

effect (Needleman et al., 1979; Winneke, 1982; Yule et

al, 1981). Investigations have also shown alterations in

electroencephalograms (EEG’s) (Burchfiel et al., 1980;

Benignus et al., 1981; Otto et al., 1982) and decreased

velocity in nerve conduction (Seppalainen and Hernberg,

1982; Feldman et al., 1977).

Many factors can affect the absorption, distribution,

and toxicity of lead. Children are more exposed to lead

than older groups because their normal hand-to-mouth

II. Background

activities introduce many nonfood items into their bodies

(Lin-Fu, 1973). Once absorbed, lead is distributed

throughout soft tissue and bone. Blood levels reflect the

dynamic equilibration between absorption, excretion,

and deposition in soft- and hard-tissue compartments

(Rabinowitz et al., 1976). Young children absorb and

retain more lead on a unit-mass basis than adults. Their

bodies also handle lead differently. Higher mineral turn-

over in bone means that more lead is available to sensitive

systems. The child's nutritional status is also significant

in determining risks. Deficiencies in iron, calcium, and

phosphorus are directly correlated with increased blood

lead levels in humans and experimental animals (Mahaf-

fey, 1981; Mahaffey and Michaelson, 1980). Increased

dietary fat and decreased dietary intake of calcium

(Barltrop and Khoo, 1975; Rosen et al., 1980), iron

(MahafTey-Six and Goyer, 1972), and possibly other nu-

trients enhance the absorption of lead from the intestine

(NAS, 1976; Barltrop and Khoo, 1975).

Since lead accumulates in the body and is only slowly

removed, repeated exposures to small amounts over

many months may produce elevated blood lead levels.

Lead toxicity is mainly evident in the red blood cells

and their precursors, the central and peripheral nervous

systems, and the kidneys. Lead also has adverse effects

on reproduction in both males and females (Lane, 1949).

New data (Needleman et al., 1984) suggest that prenatal

exposure to low levels of lead may be related to minor

congenital abnormalities. In animals, lead has caused

tumors of the kidney. The margin of safety for lead is

very small compared with other chemical agents (Royal

Commission on Environmental Pollution, 1983).

The heme biosynthetic pathway is one of the biochemi-

cal systems most sensitive to lead. An elevated EP level

is one of the earliest and most reliable signs of impaired

function due to lead. A problem in determining lead

levels in blood specimens is that the specimen may be

contaminated with lead, and thus the levels obtained may

be falsely high. Therefore, in the initial screening of

asymptomatic children, the EP level (instead of the lead

level) is determined.

The effects of lead toxicity are nonspecific and not

readily identifiable. Parents, teachers, and clinicians may

identify the altered behaviors as attention disorders,

learning disabilities, or emotional disturbances. Because

i.

1

| 1]

of the large number of children susceptible to lead poison-

ing, these adverse effects are a major cause for concern.

Symptoms and signs of lead toxicity are fatigue, pallor,

malaise, loss of appetite, irritability, sleep disturbance,

‘sudden behavioral change, and developmental regres-

sion. More serious symptoms are clumsiness, muscular

irregularities (ataxia), weakness, abdominal pain, persist-

ent vomiting, constipation, and changes in consciousness

due to early encephalopathy. Children who display these

symptoms urgently need thorough diagnostic evaluations

and, should the disease be confirmed, prompt treatment.

In this Statement, screening is distinct from diagnosis.

“Screening” means applying detection techniques to

large numbers of presumably asymptomatic children

to determine if they have been exposed to lead and, if

so, what the risks of continued exposure are. Diagno-

sis, on the other hand, means the categorization of a

child appearing to have excess exposure to lead accord-

ing to the severity of burden and toxicity so that ap-

propriate management can be started. No child with

symptoms suggesting lead toxicity should be put

through the screening process. He or she should be

brought directly to medical attention.

111. Sources of Lead Exposure

Children may be exposed to lead from a wide variety

of man-made sources. All U.S. children are exposed to

lead in the air, in dust, and in the normal diet (Figure 1).

Airborne lead comes from both mobile and stationary

sources. Lead in walter can come from piping and distribu-

tion systems. Lead in food can come from airborne lead

deposited on crops, from contact with “leaded” dust

during processing and packaging, and from lead leaching

from the seams of Jead-soldered cans. In addition to expo-

sure from these sources, some children, as a result of

their typical, normal behavior, can receive high doses of

lead through accidental or deliberate mouthing or swal-

lowing of nonfood items. Examples include paint chips,

contaminated soil and dust, and, less commonly, solder,

curtain weights, bullets, and other items.

LEAD-BASED PAINT

Lead-based paint continues to be the major source of

high-dose lead exposure and symptomatic lead poisoning

for children in the United States (Chisolm, 1971). Since

1977, household paint must, by regulation, contain no

more than 0.06% (600 parts per million (ppm)) lead by

dry weight. In the past, some interior paints contained

more than 50% (500,000 ppm) lead. The interior surfaces

of about 27 million households in this country are con-

taminated by lead paint produced before the amount of

lead in residential paint was controlled. Painted exterior

surfaces are also a source of lead. Unfortunately, lead-