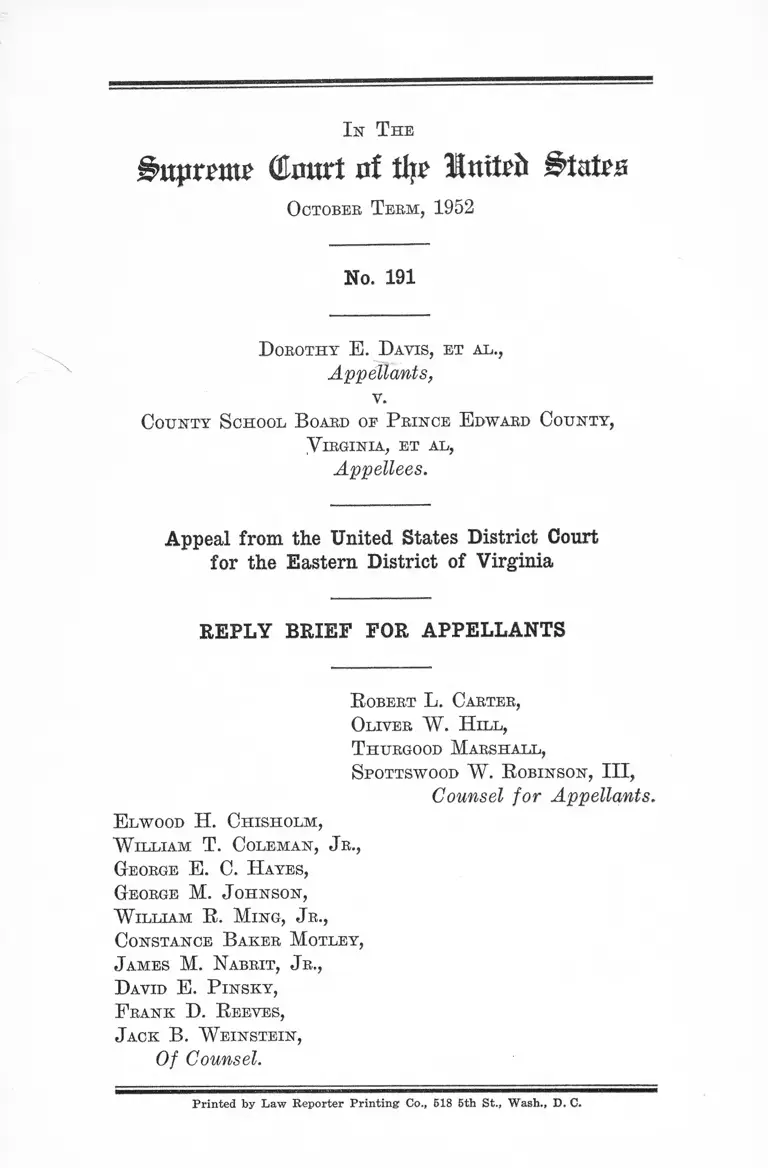

Davis v. Prince Edward County, VA School Board Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Prince Edward County, VA School Board Reply Brief for Appellants, 1952. fc26753a-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c524e6cb-e340-46d0-97cc-9fffc9e48b6b/davis-v-prince-edward-county-va-school-board-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

kapron? (tort uf tiu Imtpfc BUUb

O c t o b e r T e e m , 1952

In The

No. 191

D o r o t h y E . D a v is , e t a l .,

Appellants,

v.

C o u n t y S c h o o l B oard oe P r in c e E d w a r d C o u n t y ,

^Vi r g in ia , e t a l ,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

R o b e r t L. C a r t e r ,

O l iv e r W . H i l l ,

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

S p o t t s w o o d W . R o b in s o n , I I I ,

Counsel for Appellants.

E l w o o d H . C h i s h o l m ,

W i l l i a m T. C o l e m a n , Jr.,

G e o r g e E. C. H a y e s ,

G e o r g e M. J o h n s o n ,

W i l l i a m R. M i n g , Jr.,

C o n s t a n c e B a k e r M o t l e y ,

J a m e s M. N a b r it , Jr.,

D a v id E. P i n s k y ,

P r a n k D . R e e v e s ,

J a c k B . W e i n s t e i n ,

Of Counsel.

Printed by Law Reporter Printing Co., 518 5th St., Wash., D. C.

INDEX

Page

I. The Decisions of This Court Upon Which Appellants Rely are

Controlling ___________________________ 1

II. The Long Continued Enforcement of Educational Segregation

in Virginia Is Irrelevant__________________________ 3

III. The District Court Should Have Enjoined the Enforcement

of the Segregation Laws---------------------------------------------------------------- 4

IV . Appellees’ Predictions as to the Consequences of Desegregation

Are Belied by Experience------------------------------------------------------------- 5

V . Appellees’ Assertions and Conclusions as to the County and

State Educational Situations and Efforts to Equalize Edu

cation for Negroes Are Erroneous--------------------------------------------- 9

A . The County Picture________________________________________ 9

B. The State Picture---------------------------------------------------------------- 11

The Present Picture_________________________________________ 12

The State Supervisor’s Study_______________________________ 12

Literary Fund Allocations----------------------------------------------------- 14

The Four-Year Program____________________________________ 15

Expenditures for Instruction________________________________ 15

Teachers’ Salaries___________________________________________ - 16

VI. Conclusion __________________________________________________________ 17

TABLE OF CASES

Alston v. School Board, 112 F. 2d 992 (C A 4th 1940), cert, denied

311 U. S. 693__________________________________________________________ 8

Atlantic Coastline Railroad Co. v. Chance, 186 F. 2d 879 (C. 4th

1951), 341 U . S. 941; 198 F. 2d 549 (CA 4th 1952), — IT. S. —

(Nov. 10, 1952)_______________________________________________________ 4

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, 182 F . 2d 531 (CA 4th

1950) __________________________________________________________________ 13

Corbin v. County School Board of Pulaski County, 177 F. 2d 929

(C A 4th 1950)________________________________________________________ 13

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78________________________________________ 1 ,2

Hale v. Kentucky, 303 U. S. 613_________________________________________ 3

Henderson v. United States, 339 U . S. 816______________________ _______ 3

Inland Waterways Corporation v. Young, 309 U . S. 517---------------------- 3

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268__________________________________________ 3

i

Page

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U . S. 637_________________ 2

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337______.1—111-_____ 2, 3 ,10

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 272_._______ __________________________ 3

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463.-____________________________________ 3

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354___ __-—1.11—____i_____ ___1______ 3

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537______ _________________________________ 1, 2

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1____________________________________ _____ 3

Sipuel y . Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631__________________________ 2, 3, 5

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649________________________________________ 3

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629_____________________________________ 2, 3, 5

STATUTES CITED

Virginia Code, 1950, Sec. 22-223 to 22-229______ ...______________________ 10

AUTHORITIES CITED

Bustard, The New Jersey Story: The Development of Racially Inter-

grated Public Schools, 21 Journal of Negro Education 275, (1952) 8

Freedom to Serve, Report of President’s Committee on Equality of

Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services (1950)____ 6 ,7

NOTES

Grade School Segregation: The Latest Attack on Racial Discrimina

tion, 61 Yale Law Journal, 730__________________________ 7

MISCELLANEOUS

20 Annual Report of Superintendent of Public Instruction No. 3,

September, 1937_____________________________________________________ 10

24 Annual Report of Superintendent of Public Instruction No. 3,

September, 1941___________________________________________________ 10

30 Annual Report of Superintendent of Public Instruction No. 3,

September, 1947__________ _________________—__________________________ 10

33 Annual Report of Superintendent of Public Instruction No. 3,

September, 1950__________________.____ _______________________________ 10

X X X IV Annual Report of Superintendent of Public Instruction No. 4,

September, 1951__________________________ ________________________ 13,14

ii

Ik T he

i © m a r t ni Oft Inttpi*

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1952

No. 191

D o r o t h y E . D a y is , e t a l .,

Appellants,

v.

C o tjh ty S c h o o l B oard o f P r ik c e E d w a r d C o u n t y ,

V ir g i n i a , e t a l ,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

ARGUMENT

I .

THE DECISIONS OF THIS COURT UPON W HICH

APPELLANTS RELY ARE CONTROLLING

Appellees assert that the cases relied upon by appellants

(Appellants’ Brief, pp. 9-11) are not in point and that

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, and Gong Lum v. Rice,

2

275 TJ. S. 78, control here (Appellees’ Brief, pp. 13-15). We

stand on our brief in chief that the Plessy and Gong Lum

cases are not controlling here (Appellants’ Brief, pp. 13-

15).

Appellees argue that different legal considerations ob

tain as between (a) “ situations where the parties seeking

relief were wholly denied the right in question without

being afforded ‘ separate but equal’ treatment” and (b)

those “ where coordinate facilities or opportunities are

provided” (Appellees’ Brief, p. 14). In this vein they at

tempt to distinguish Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305

TJ. S. 337, and Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631.

The difference claimed is constitutionally irrelevant.

Provision for Negroes of facilities unequal to those af

forded whites is as much a denial of the equal protection of

the laws as is a total failure to provide for Negroes facili

ties which are afforded whites. The consequences of the

Gaines and Sipuel cases are unchanged by provision for

separate but educationally unequal facilities and opportu

nities. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 TJ. S. 629; McLaurin v. Okla

homa State Regents, 339 TJ. S. 637.

Appellees seek to dismiss the Siveatt decision as inappli

cable on grounds that (a) “ the considerations relative to

education at the graduate level are entirely different from

those bearing on the high school” and (b) “ the Court there

found inequality because of circumstances which have no

substantial bearing here.” (Appellees’ Brief, p. 15). They

claim that the McLaurin case “ was a case of manifest

harshness, and the facts there presented provide adequate

distinction here.” (Appellees’ Brief, p. 15). Neither of

these grounds affords adequate distinction. In both of

those cases this Court’s effort was to determine whether

the practice complained of in fact resulted in a denial of

equal educational opportunities. Here the record discloses,

and the District Court found, that equal educational oppor

tunities are not available. Certainly, the legal issue is the

3

same where segregation diminishes the Negro’s share of

the benefits of a high school education as where segrega

tion diminishes his share of the benefits of a graduate

education.

II.

THE LONG CONTINUED ENFORCEMENT OF EDU

CATIONAL SEGREGATION IN VIRGINIA IS IRREL

EVANT.

Appellees suggest that the fact that racial segregation

in public education has been Virginia’s practice for more

than eighty years is important (Appellees’ Brief, pp. 2,

17, 21). The evidence of appellees shows that Negro stu

dents have been victimized by discrimination at least since

1918 (R. 394-400). Appellees concede that discrimination

of this kind violates rights secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment (Appellees’ Brief, p. 29). Eighty years of

such discrimination could not make that practice valid.

Similarly, the duration of the segregation practice is irrele

vant to a determination of its constitutionality. 1‘ Illegality

cannot attain legitimacy through practice.” Inland Water

ways Corporation v. Young, 309 U. S. 517, 524.

Indeed, most of the racially invidious practices which

this Court has stricken down had existed for many years:

exclusion of Negroes from public graduate and professional

schools, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337;

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631; Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U. S. 629; residential segregation by court enforced

restrictive covenants, Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; sys

tematic exclusion of Negroes from jury service, Hale v.

Kentucky, 303 U. S. 613; Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354;

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463; restrictions upon the

right to vote; Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268; Smith v. All-

wright, 321 U. S. 649; segregation of interstate passengers

by statute or carrier regulations, Morgan v. Virginia, 328

U. S. 272; Henderson v. United States, 339 II. S. 816. See

4

Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Co. v. Chance, 186 F. 2d 879

(CA 4th 1951), cert, denied 341 U. S. 941, 198 F. 2d 549

(CA 4th 1952), cert, denied ___ U. S. ___ (November 10,

1952).

III.

THE DISTRICT COURT SHOULD HAVE ENJOINED

THE ENFORCEMENT OF THE SEGREGATION LAWS

Appellees contend that even though the physical high

school facilities for Negro students are presently unequal

to those for white children, this inequality will be remedied

by September, 1953, and that the District Court was correct

in suspending appellants’ constitutional rights until then

(Appellees’ Brief, pp. 36-39).

Under even their own concept, appellees are constitu

tionally obligated to provide equal facilities. For many

years they have disregarded that obligation and now seek

to avoid the consequences. Their strenuous effort to rem

edy the present conditions serves but to emphasize the

gravity of current physical inequalities.

Appellants cannot concur in appellees’ statement (Appel

lees’ Brief, p. 33) that “ equality now exists for all practi

cal purposes as to curricula.” Comparison of present

curricula in the three high schools in the county, as set

forth in their respective Preliminary Annual High School

Reports for the 1952-53 session, now on file in the State

Department of Education of Virginia, discloses that there

are a number of courses now taught in one or more of the

white high schools which are not taught in the Negro high

school. And it is apparent that equalization of physical

facilities will not eliminate other educational inequalities

which are inherent in the practice of segregation.

Proof that appellees have drafted and placed in motion

plans seeking to equalize the physical facilities is no bar

to a decree enjoining segregation in the public schools.

Denial of prompt relief cannot be reconciled with the pro

nouncements of this Court. Since the right to the equal

5

protection of the laws is “ personal and present,” appel

lants cannot be denied the only effective relief that is

presently available. Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S.

631; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629.

IV.

APPELLEES’ PREDICTIONS AS TO THE CONSE

QUENCES OF DESEGREGATION ARE BELIED BY

EXPERIENCE.

Appellees say they do not seek “ to threaten or to coerce”

(Appellees’ Brief, p. 29), but the consequences which they

assign to desegregation can hardly be termed an appeal to

reason. Similar predictions were made in the brief of

eleven southern states, including Virginia, amici curiae in

support of the respondents, in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S.

629, where it was said (p. 11) :

“ Briefly summarized, the Southern States know that

intimate social contact in the same schools will lead to

withdrawal of public support of the schools, to physi

cal and social conflicts, and to discontent and unhappi

ness for both races.”

Despite this prediction, desegregation has taken place in

universities and colleges in the South, including Virginia,

without these consequences.

Efforts to conform existing patterns to the Constitution

have almost invariably been accompanied by forecasts of

dire consequences. The evidence derived from observa

tions and systematic study of situations of desegregation

is summarized and analyzed in the Appendix to Appellants ’

Brief (pp. 13-17). It potently demonstrates that appellees’

claims are unfounded.

Appellees say that desegregation experience at the uni

versity level affords no precedent for high school desegre

gation because the former involved too few Negroes and

claim that the problem becomes acute when Negroes con

6

stitute a substantial portion of the school population (Ap

pellees’ Brief, p. 30). The experience of integration in the

armed services furnishes concrete evidence that this posi

tion is without merit.

The President’s Committee on Equality of Treatment

and Opportunity in the Armed Services found that “ in the

relatively short space of five years the Navy had moved

from a policy of complete exclusion of Negroes from gen

eral service to a policy of complete integration in general

service.” 1 On January 1,1950, the Negro enlisted strength

in the Navy was 15,747 out of a total of 330,098, or 4.7 per

cent, of which total 6,647, or 2 per cent, were in general

ratings.2 The Committee reported that3

“ Confronted by the Navy experience, some military

officials maintained that it did not provide a reliable

basis for generalization because of the relatively small

number of Negroes involved. If, these officials sug

gested, Negroes had comprised 7 to 10 percent of the

men in general service rather than 2 percent, the Navy

experience might have been quite different.

“ The Committee was skeptical of this argument, but

it could not gainsay it without concrete evidence to the

contrary. The experience of the Air Force has sup

plied that evidence.”

On January 31, 1950, after the first eight months of its

integration program, there were 25,702 Negroes in the Air

Force of whom 74 per cent had been integrated.4 The

number of integrated units totaled 1,301; the number of

predominantly Negro units remaining was only 59.5 The

Committee reported that experience bore out the conclu

sion that6

1 Freedom to Serve, Report of President’s Committee on Equality of

Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services (1950), p. 23.

2 Id. at 24.

3 Id. at 33.

4 Id. at 43.

c Id. at 43.

0 Id. at 44.

7

“ Integration of the two races at work, in school, and

in living quarters did not present insurmountable dif

ficulties. As a matter of fact, integration in two of the

services had brought a decrease in racial friction.”

Integration is now the official policy of the Army, where

Negroes constitute 9 to 10 per cent of the total enlisted

personnel.7 The success of integration in the armed serv

ices furnishes conclusive proof that, irrespective of the

number involved, desegregation can occur even in areas

where there is far more personal association than in

schools.

Appellees also discount successful desegregation in uni

versities on grounds that immaturity of the student and

stronger parental influence place the high school in a special

category (Appellees’ Brief, pp. 28-29). Here again the

claim is refuted by experience. Recently, desegregation

has taken place at both the elementary and secondary

school levels in areas where segregation had existed for

long periods of time.8 Speaking of desegregation recently

occurring in a Baltimore high school, Maryland’s Gover

nor Theodore R. McKeldin said9

“ For a long time, # # the City of Baltimore op

posed the employment of Negro policemen. But when

a number of Negroes were assigned to police duty,

* * * ‘ the evils which had been predicted did not

materialize—the heavens did not fall and there was no

increase in racial tension.’

“ Similarly, * * * the established practice in the

Baltimore public school system had been to segregate

the two races. When the school board decided to open

the doors of a high school to eligible Negroes because

in no other way could equal facilities be established,

* * * the ‘ lurid’ predictions of racial conflict failed to

1 Id. at 61-63.

8 For a review of a number of instances of recent elementary and high

school desegregation, see Note, Grade School Segregation: The Latest

Attack on Racial Discrimination, 61 Yale Law Journal, 730, 740, notes

44-47 (1952).

8 A s reported in N. Y . Times, November 10, 1952.

8

materialize, and experience is showing that white and

Negro youths get along harmoniously.

“ ‘ The fact is that in this instance, as in the case

of other prejudices, * * * what was considered an im

mutable pattern was found when challenged to have no

validity either in social justice or the feelings of the

community.’ ”

The short answer to the claim that desegregation will

cause many Negro teachers to lose their jobs (Appellees’

Brief, p. 30) is that the rights asserted by these appellants

are personal to the complaining students and parents and

can in no wise be affected by such consideration. The

fallacy in the argument is even greater. The Fourteenth

Amendment, which prohibits racial discrimination in the

payment of teachers’ salaries, Alston v. School Board, 112

F. 2d 992 (CA 4th, 1940), cert, denied 311 U. S. 693, would

likewise forbid racial discrimination in the employment of

teachers. Moreover, we invite the Court’s attention to the

experience in New Jersey where desegregation increased

the job opportunities for Negro teachers.10

“ “ Until recently, most opportunities for colored teachers in New Jer

sey existed in the areas where segregated schools were located. This is

shown by a study of the figures regarding the number of colored teachers

employed in New Jersey in 1945-46. In that year, there were 455 ele

mentary and 24 secondary colored teachers in the public schools for a

total of 479. A t that time, of these, 395 elementary and 20 secondary,

for a total of 415 teachers, were engaged in the nine counties that main

tained segregated schools. A recent study shows that today in these

same nine counties, there are 391 elementary and 34 secondary, for a

total of 425 colored teachers in these same areas. On the other hand,

while there was a total of 479 colored teachers in all the public schools of

the State in 1945-46, today the same study shows 582 elementary and 63

secondary for a total of 645 or a state-wide gain of 166 colored teachers

during the last six years. It would seem from further examination of the

figures that while teachers did not lose their jobs as the result of integra

tion, there was a temporary slow-up in hiring additional colored teachers

in some of the districts involved. The figures for the State as a whole,

however, show a decided gain in this field of employment. As a result

of the same recent visits referred to earlier by staff members of the

Division to all of the school districts involved in the New Jersey program,

reports indicate a very healthy attitude toward employment of all future

teachers on merit and not on race.” Joseph L. Bustard, The New Jersey

Story: The Development of Racially Integrated Public Schools, 21

Journal of Negro Education, 275, 284 (1952).

9

It bears repeating that none of the dire predictions made

to this Court by tbe proponents of segregation and dis

crimination have ever materialized. It is evident that the

issues in this case should be examined free of the pressures

and restraints which appellees seek to inject.

V.

APPELLEES’ ASSERTIONS AND CONCLUSIONS AS

TO THE COUNTY AND STATE EDUCATIONAL SITU

ATIONS AND EFFORTS TO EQUALIZE EDUCATION

FOR NEGROES ARE ERRONEOUS,

Appellees labor to demonstrate their good faith and as

sert that they have in the past attempted and now are

effecting county-wide and state-wide educational equality

for Negroes (Appellees’ Brief, pp. 18-21, 34-35). This does

not meet the issue in this case or disprove appellant’s thesis

that educational inequality is an inseparable eoncomimt-

ant of educational segregation. Furthermore, the true

picture in the county and the state is not what appellees

draw.

A. The County Picture

The District Court found that the Negro high school is

inferior to the white high school as to buildings, facilities,

curricula and buses (R. 622, 624). The evidence demon

strated that the differentials are substantial and them-*

selves rendered it impossible for Negro students to obtain a

high school education equal to that afforded white stu

dents (R. 80-120; 122-131).

Appellees attempt to escape indictment on this count by

pointing to the fact that the 1951 enrollment of Negro

high school students was 223 per cent of the 1941 enroll

ment while during the same period the white high school

enrollment declined 25 per cent—an increase they contend

was unexpected (Appellees’ Brief, pp. 4, 34). The smaller

1941 Negro high school enrollment did not justify the cis-

10

criminations which, for many years have been made against

those Negro students who were in school. Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v, Canada, 305 IT. S. 337. Nor does the contention

that the increase was unexpected bear scrutiny. Virginia

requires its school boards to take a quintennial census of

all persons of school age residing in each county and city,

and to gather statistics relating to the interests of educa

tion in their respective districts.11 The published school

census figures show that in Prince Edward County the

potential Negro school enrollment—children between 7 and

19 years of age—has greatly exceeded the potential white

school enrollment for a number of years:12

1935

Census

1940

Year

1945 1950

Negro 2,948 2,298 2,296 2,252

White 2,040 1,929 1,639 1,537

Kegro/White Ratio 1.4 1.2 1.4 1.5

It is .evident that excesses of such size and duration were

reflected at both the high school and elementary school age

levels and refute the contention that the increase was un-

expectable.

the history of high school education in Prince Edward

County is one of gross discrimination against Negro stu

dents. In 1918, when the present Superintendent took

Jffice, there was a high school for white students (R. 394).

It was not until 1927 that any such provision was made for

Negro students (R. 394). In that year, a Negro combina

tion elementary-high school was provided (R. 394). This

11 Virginia Code, 1950, Sec. 22-223 to 22-229.

\ 12 20 Annual Report of Superintendent of Public Instruction No. 3,

September 1937, Table IX , Summary of School Census, 1935, at p. 137;

24 Annual Report of Superintendent of Public Instruction No. 3, Sep

tember 1941, Table 20, School Census, 1940, at pp. 224-225; 30 Annual

Report of Superintendent of Public Instruction No. 3, September 1947,

Table 56, School Census, 1945, at pp. 264-265; 33 Annual Report of

Superintendent of Public Instruction No. 3, September 1950, Table 57,

Sehe'ol Census, 1950, at pp. 266-267. These reports are published an-

nuiily by the Commonwealth of Virginia, an appellee here.

11

school was not accredited by the State until 1931 (R. 397).

Unlike the Farmville High School for whites, neither this

school nor its successor, the Moton High School, earned

regional accreditation (R. 119). Although white high

school students have been afforded gymnasium facilities

since 1927 and cafeteria facilities since 1936,' no such facili

ties have yet been afforded Negroes (R. 401-402). The

Farmville High School, constructed in 1936, was designed

to accomodate more than twice its then enrollment, but

the Moton High School, constructed three years later, was

designed to accomodate only 25 more students than its

enrollment at the time of constructioi (R. 401-402). Free

school transportation has been afforded white students

since 1924, but was not afforded Negro students until 1938

(R. 395). These are among the many inequalities that

have existed through the years.

Appellees point to plans for the new Negro high school

which they urge will, upon completion, provide better

facilities than those now provided white students (Appel

lees’ Brief, p. 35). This ignores the plans for new white

construction in the county. When all the presently pro

posed new construction is completed (D. Ex. 96, R. 359),

$2,187.50 per white high school student will be invested

in wThite high school property while only $1,792.11 per

Negro high school student will be invested in Negro high

school property—a ratio of 82 cents per Negro student for

every dollar invested per white student (R. 577; P. Ex.

102, Table 17, R. 573). Thus, the superiority of Negro

facilities will only be temporary, and the familiar pattern

again will obtain.

This is the picture in Prince Edward County, present,

past and future. The single theme portrayed is that .segre

gation in public schools inevitably perpetuates inequality.

B. The State Picture

Here appellees contend that “ substantial inequality no

longer exists” (Appellees’ Brief, p. 18). Even if such

12

were the fact, it would be irrelevant to this case, which in

volves the personal constitutional rights of Negro high

school students in Prince Edward County. But such is

not the fact.

The Present Picture:

This is the present situation in Virginia as to physical

facilities (PI. Ex. 102, Table 14, R. 573):

_ 1950-51

White Negro

Enrollment: ___________________ 464,330 160,811

Percentages:_________________ 74% 26%

Value of School Property: $ $

Sites and Buildings:_________ 170,285,836 36,199,490

Average per pupil enrolled_ 366.73 225.11

Negro/White ratio_________________ .61

Furniture and Equipment:_____ 17,245,525 3,551,166

Average per pupil enrolled__ 37.14 22.08

Negro/White ratio_________________ .59

Busses: _______________________ 5,170,621 1,207,082

Average per pupil enrolled_ 11.14 7.51

Negro/White ratio_________________ .67

Total School Property:_________ 192,701,982 40,957,738

Average per pupil enrolled__ 415.01 254.69

Negro/White ratio _________________ .61

Thus, for each dollar invested in each category per white

student, the investment per Negro student is 61 cents in

sites and buildings, 59 cents in furniture and equipment,

67 cents in busses and 61 cents in total school property.

The State Supervisor’s Study:

Appellees emphasize the District Court’s finding that in

63 of Virginia’s 127 cities and counties high school facili

ties for Negroes are equal to those for whites and that in

30 of these 63 counties and cities they are or soon will be

better than those for whites (R. 619; Appellees’ Brief, p.

19). This finding was predicated upon the conclusions ex

13

pressed by the State Supervisor of School Buildings based

upon a study he made (R. 349; P. Ex. 10, R. 341). While

this study considered only school sites, buildings and physi

cal equipment, and did not embrace curricula, instructional

personnel, and other educationally significant factors (B.

347), appellants submit that neither the study nor the con

clusions drawn therefrom are valid.

The witness admitted that he did not inspect the entirety

of Virginia’s facilities for this purpose (R. 346) and that

the compilation consisted of “ ideas, of records, people,

State Department personnel, architects on the outside.”

(R. 347). While the study embraced proposed, as well as

existing, construction of Negro schools, it did not take into

account proposed construction of white schools (R. 346).

According to the latest published report of the Superin

tendent of Public Instruction,13 there are two or more ac

credited white high schools but only a single accredited

Negro high school in 25 of the 50 counties and 2 of the 13

cities included in the Supervisor’s list, and 13 of these 25

counties have from 4 to 9 accredited white high schools.

In these situations the white high school facilities were

averaged and the average compared with the Negro high

school facility (R. 348-9). Since the caliber of the better

white facilities is reduced when averaged with the poorer

white facilities, some of the white students are afforded

facilities superior to the average. This method of measur

ing equivalency of facilities has been condemned. Corbin

v. County School Board of Pulaski County, 177 P. 2d 929

(CA 4th 1949); Carter v. School Board of Arlington

County, 182 F. 2d 531 (CA 4th 1950).

Examination of the aforesaid report also reveals that in

17 of the counties and 5 of the cities on the Supervisor’s

list the Negro high school is not accredited by the Southern

“ X X X IV Annual Keport of the Superintendent of Public Instruction

No. 4, September 1951, Table 7, Accredited High Schools, at pp. 39-64;

Table 9, Qualified High Schools, at p. 94; Table 11, Certified High

Schools, at pp. 98-102. See note 12.

14

Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, while at

least one white high school facility in each of such areas is ;

that in 3 of the counties and 2 of the cities in the list there

is either no Negro high school or the Negro high school is

not accredited by the State, while there is at least one white

high school in each of such areas which is so accredited;

and that in 7 of the counties and 2 of the cities on the list

there was at least one white high school offering work

through the twelfth grade, but the Negro high school pro

gram offered work only through the eleventh grade.14

Literary Fund Allocations:

Appellees emphasize the approximately 65 million dol

lars allocated by the State Literary Fund for school con

struction in the State (Appellees’ Brief, p. 19). Specific

projects have been approved for 69 of Virginia’s 100 coun

ties and 22 of her 27 cities, and approximately 71 per cent

of this sum is to be spent on white schools and 29 per cent

on Negro schools (D. Ex. 108, Table XVII, R. 426). Even

this large expenditure, when added to the value of the pres

ent sites and buildings, will increase the ratio of invest

ment from the present 61 cents to only 74 cents per Negro

student for every dollar invested per white student (P. Ex.

102, Table 15, R. 573). Since no time has been set for the

completion of these projects, it cannot be estimated when

even this ratio will be realized (R. 576). Even if all of

the proposed Negro projects were completed and no addi

tional monies whatever were invested in the white schools,

the amount of money invested in sites and buildings per

Negro student would be only $343.30 (P. Ex. 102, Table 15,

R. 573), as compared to $366.73 already invested per white

student (P. Ex. 102, Table 14, R. 573).

“ X X X I V Annual Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction

No. 4, September 1951, Table 7, Accredited High Schools, at pp. 39-64;

Table 9, Qualified High Schools, p. 94; Table 11, Certified High Schools,

at pp. 98-102. See note 12.

15

The Four Year Program:

Appellees also point to tlie so-called four-year plan pro

posing expenditure of some 263 million dollars for new

construction and improvements, of which 71.7 per cent will

be spent on white projects and 28.3 per cent on Negro

projects (Appellees’ Brief, p. 20). These projects are

planned for 99 counties and 25 cities (R.430). The money

for this program is not now available (E. 484). Even if

available and the entire program completed by 1956, the

amount invested in sites and buildings would be only 79

cents per Negro student for each dollar per white student

(P. Ex. 102, Table 16, 11. 573). Even if funds were avail

able to enable the State to continue the program after

1956 at the same ambitious rate, investments in buildings

and sites per Negro and per white student would not be

equal until the 1963-64 school session (R. 56/).

Expenditures For Instruction:

Appellees point to an increase in the total amounts spent

in 1950-51 for instruction in regular day schools of 123

per cent in white schools and 161 per cent in Negro schools

over the expenditures for 1943-44 (Appellees’ Brief, p. 19).

In 1943-44 only 85 cents, and in 1950-51 only 89 cents, was

spent per Negro student for each dollar spent per white

student (R. 574; P. Ex. 102, Table 13, R. 573). Thus, the

increase during this eight year period was only 4 cents

per Negro student (R. 575). Even if the percentage in

crease favorable to Negro schools continued at the same

rate obtaining during the 8 year period, expenditures for

instruction would not be equalized to school population

ratios for twenty years, or until the 1972-73 school session

(R. 575).

Appellees also point to the fact that the expenditures

for 1950-51, when the school population ratios were 74.3

per cent white and 25.7 per cent Negro, were 76.4 per cent

16

for white schools and 23.6 per cent for Negro schools (Ap

pellees’ Brief, p. 19). But at no time during the eight year

period has the ratio of expenditures in Negro schools

equalled the ratio of Negro students to the total school

population (D. Ex. 108, Table 11(a), R. 426; D. Ex. 109,

Table 1(a), R. 440). The difference between these ratios

has ranged from 5.4 per cent in 1943-44 to 2.1 per cent in

1950-51 (D. Ex. 108, Table 11(a), R. 426; D. Ex. 109, Table

1(a), R. 440). The difference in 1943-44 was 20 per cent,

and in 1950-51, 10 per cent, of the entire amount spent

for Negro instruction (D. Ex. 108, Table 11(a), R. 426).

Equalization of the ratios of expenditures to the school

population ratios would have necessitated the addition in

each of the eight years of more than a million dollars to

the appropriations for Negro schools (D. Ex 108, Table II

(a), R. 426).

Teachers’ Salaries:

Appellees assert that the average annual salary of Negro

elementary teachers is somewhat larger than that of white

teachers, although the average annual salary of Negro high

school teachers is smaller than that of white high school

teachers (Appellees’ Brief, p. 18). A more accurate picture

is obtained by comparing the per capita costs of salaries

per student in average daily attendance. For 1950-51 these

were $78.49 for whites and $73.15 for Negroes in elementary

schools, and $148.21 for whites and $130.07 for Negroes in

high schools (P. Ex. 102, Table 14, R. 573). Thus, for

each dollar spent in each category per white student, the

expenditure per Negro student is only 93 cents in elemen

tary schools and 88 cents in high schools (P. Ex. 102,

Table 14, R. 573). Since the per capita costs of salaries

are substantially greater for white teachers than for Negro

teachers, both on the elementary and the high school levels,

the inescapable inference is that the average student load

of Negro teachers is larger than that of white teachers.

17

The state-wide picture thus emerges as a futuristic pro

jection of inequality despite its grandiose design, and

affords little hope that Negro students will receive equality

of education in Virginia in the forseeable future under

the system of separate schools.

CONCLUSION

We respectfully submit that, for the reasons stated

herein and in appellants’ initial brief, the decree of the

District Court should be reversed.

R o b e r t L. C a r t e r ,

O l iv e r W. H i l l ,

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

S p o t t s w o o d W. R o b in s o n -, III,

Counsel for Appellants.

E l w o o d H . C h i s h o l m ,

W i l l i a m T. C o l e m a n , Jr.,

G e o r g e E. C. H a y e s ,

G eo r g e M. J o h n s o n ,

W i l l i a m R. M i n g , Jr.,

C o n s t a n c e B a k e r M o t l e y ,

J a m e s M. N a b r it , Jr.,

D a v id E. P i n s k y ,

F r a n k D . R e e v e s ,

J a c k B . W e i n s t e i n ,

Of Counsel.