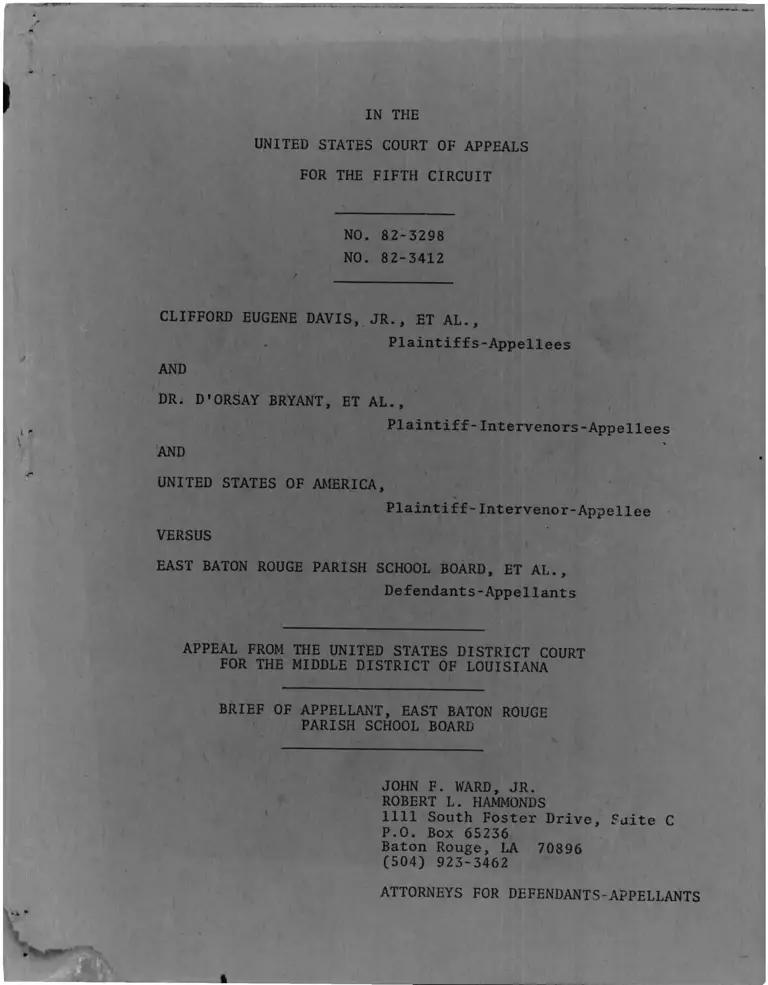

Bryant v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board Brief of Appellant

Public Court Documents

July 29, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bryant v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board Brief of Appellant, 1983. 990d0228-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c52ccd72-d9f3-4b61-8a2a-473624462dbc/bryant-v-east-baton-rouge-parish-school-board-brief-of-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 82-3298

NO. 82-3412

CLIFFORD EUGENE DAVIS, JR., ET AL.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

AND

DR. D'ORSAY BRYANT, ET AL.,

Plaintiff-Intervenors-Appellees

AND

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellee

VERSUS

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellants

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF OF APPELLANT, EAST BATON ROUGE

PARISH SCHOOL BOARD

JOHN F. WARD, JR.

ROBERT L. HAMMONDS

1111 South Foster Drive, Suite CP.O. Box 65236

Baton Rouge, LA 70896(504) 923-3462

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

IX THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 82-5298

NO. 82-5412

CLIFFORD EUGENE DAVIS, JR., ET A L .,

Plaintiffs-Appel lees

AND

DR. D'ORSAY BRYANT, ET AL.,

Plaintiff-Intervenors-Appellees

AND

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-App e11e e

VERSUS

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellants

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF OF APPELLANT, EAST BATON ROUGE

PARISH SCHOOL BOARD

t

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

STATEMENT WITH REGARD TO ORAL ARGUMENT (i)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (ii)

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION 1

STATEMENT OF ISSUES 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 2

(i) Course of Proceedings and Disposition

in Court Below 2

(ii) Statement of Facts . 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 13

ARGUMENT 15

I. WHAT DO THE SUPPLEMENTAL ORDERS OF

THE DISTRICT COURT REQUIRE AND WHAT

IS THE LAW WITH RESPECT THERETO? 15

A. ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ASSIGNMENT 15

B. HOLDING SCHOOL BOARD RESPONSIBLE

FOR FAILURE OF ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

PLAN DUE TO "WHITE FLIGHT" 17

C. BATON ROUGE MAGNET HIGH SCHOOL

RACIAL QUOTA 32

D. SCOTLANDVILLE MIDDLE SCHOOL RACIAL

QUOTA 34

E. OTHER ACTIONS AND REQUIREMENTS OF

THE DISTRICT COURT WHICH INTRUDE

INTO THE DAY-TO-DAY OPERATION OF THE

SCHOOLS BEYOND THE JURISDICTION AND

AUTHORITY OF A DISTRICT COURT 45

CONCLUSION 49

CERTIFICATE 50

STA T E M E N T WITH REGARD TO ORAL A R G U M E N T

The two consolidated appeals which are the subject

of this brief are the third and fourth appeals arising out

of this litigation. The first and second appeals (No. 81-3922

and No. 81-3476) have been briefed and are presently pending in

this Court, but have not yet been argued. We pointed out in

brief in the previous appeals that the first years implementation

of the District Court's desegregation plan (elementary schools

only) for the 1981-82 school year resulted in the loss of approxi

mately 4,000 white students from the school system.

With implementation of the secondary school plan (middle

schools, 6-8 and high schools, 9-12) for the 1982-83 school year,

approximately 3,000 more white students left the school system.

With the addition of the subsequent orders of the District Court,

which are the subject of these two consolidated appeals, early

projections indicate an additional loss of over 1,000 students.

In view of the adverse impact of the decision and orders of

the Court below on this community and its public school system,

the establishment of racial quotas and racial requirements for

admissions to particular schools by the District Court and the

changed position of the United States as evidenced by its previous

motion for a stay of appellate proceedings, defendants-appellants

respectfully suggest that the issues are of sufficient importance

and complexity that oral argument will be helpful to the Court and

is both necessary and desirable.

(i)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Andrews, et al. v. City of Monroe, et al.,

CA No. 11,297 ..................................... 56

Austin Independent School District v.

United States, 429 U.S. 990, 50 L.Ed.2d

603 , 97 S.Ct. 517 (1977).......................... 29, 49

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74

S.Ct. 686, 98 L .Ed.2d 873 (Brown I - 1954)

and 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed.2d

1083 (Brown II - 1955)............................ 2 , 47

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 64 L.Ed.2d

47 , 100 S.Ct. 1490 (1980)........................ 29

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S.

449, 61 L.Ed.2d 666, 99 S.Ct. 2941, reh den

62 L. Ed. 2d 121, 100 S.Ct. 186 (1979)............. 29

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board,

498 F. Supp. 580 (M.D. La. 1980)................. 5 , 9 , 11

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 453 U.S.

406, 53 L .Ed.2d 851, 97 S.Ct. 2766 (1977)

(Dayton I)......................................... 29,48

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526, 61 L.Ed.2d 720, 99 S.Ct. 2971 (1979)

(Dayton I I ) ....................................... 29

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 88

S.Ct. 1689 , 20 L . Ed. 2d 716 (1968) at 439 ......... 48

Hecht Company v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321, 329-330

(1944).............................................. 48

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 94 S.Ct. 3112,

41 L. Ed. 2d 1069 (1974)............................ 16, 28 , 44 ,

49

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424, 49 L.Ed.2d 599, 96 S.Ct.

2697 (1976)....................................... 29 , 50 , 49

Pierce v. Society of Sisters,268 U.S. 510, 45

S.Ct. 571 , 69 L . Ed. 2d 1070 (1925)............... 35

(ii)

CASES PAGE

Ross v. Houston Independent School District,

— F.2d (No. 81-2323, 5th Cir. Feb.

167 19831- ......................................... 29

San Antonio School District v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 1 , 50 (1973).............................. 49

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 419 F . 2d 1211 (Tth Cir.

1 9 6 9 ) .............................................. 3

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklinberg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d

554 ................................................ 16, 28, 44 ,

49

Taylor, et al. v. Ouachita Parish School

Board, et al. , CA No. 12,171.................... 36

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

— Education, 380 F .2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967)

(en banc) modifying 372 F.2d 836 (1966) . . . . 2

United States v. Southpark Independent School

District, 566 F.2d 1221 (5th Cir. 1978) . . . . 29

United States v. Texas Educational Agency,

606 F . 2d 518 (5th Cir. 1979). 7 . .............. 29

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Board, 646 F.2d

925 , 944 (5th Cir. 1981)........................ 35 , 41

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corporation, 429 U.S.

252, 50 L .Ed.2d 450, 97 S.Ct. 555 (1977). . . . 29

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) ..................................... 49

(iii)

STATEMENT OF J U R I S D I C T I O N

These are consolidated appeals from separate final

judgments or orders of the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Louisiana. This Court has

jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. 1291.

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

I. Does the District Court's pursuit of acheiving

a racial balance in virtually every school, as

further exemplified by the supplemental orders

here appealed from, go beyond constitutional

requirements and the requirements of existing

decisions of the Supreme Court and this Court?

II. Do the District Court's supplemental orders

which, among other things, establish flat racial

quota enrollments at certain schools, establish

purely racial entrance requirements for certain

schools, and establish preferential treatment

for students who attend one particular school

under his order, clearly exceed the authority of

the District Court?

III. Is the District Court's plan of May 1, 1981 as

supplemented by these subsequent orders, contrary

to the constitution and decisions of the Supreme

Court and this Court in that the remedy now far

exceeds the violation?

IV. Do the written and verbal directives issued to

the School Board with regard to the day-to-day

operation of the school system regarding curriculum,

maintenance of facilities, use of closed facilities,

investigating student residences, etc. go beyond

the jurisdiction and authority of the District Court?

STATEMENT OF THE CAS E

(i) Course of Proceedings and Disposition in Court Below

This school desegregation case vas originally filed on

February 29, 1956. (Record, Vol. 1, Page 1). Thereafter,

the parties here, as in other communities throughout the

South, tried to find the practical meaning of the Supreme

Court's decisions in Brown v. Board of Education, 547 U.S.

483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed. 873 (Brown I--1S54) and -349 U.S.

294 , 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1 083 (Brown 11-0 955).

The East Baton Rouge Parish School System was first

before this Court in the consolidated cases entitled United

States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 380 F. 2d

385 (5th Cir. 1967)(en banc), modifying, 372 F. 2d 836

(1966). On remand from that decision, the School Board

called together all of the civic and community leaders in

the black community in an attempt to find solutions to this

problem at the community level. This resulted in the Board s

voluntarily creating a bi-racial committee to develop a

complete and final plan for desegregation of schools in East

Baton Rouge Parish. (Record, Vol. 3, Pages '40 and /41).

After many meetings of this Bi-racial Committee and its

two sub-committees (one studying faculty desegregation and

one studying student desegregation), the Bi-racial Committee

recommended to the School Eoard and the School Board adopted

- 2 -

and filed with the District Court for implementation for

the 1 970- 71 school year., a neighborhood school-type desegre

gation plan. (Record, Vol. 3, Rages 747-765). This plan

thoroughly desegregated all schools located in the central

part of the parish from north to south, including the schools

in the two (2) smaller towns of Baker and Zachary. Because

of racial residential impaction, there were some predominantly

black schools on the far west side of the parish by the

Mississippi River and some predominantly white schools on the

far eastern side of the parish where there are virtually no

black residents. This plan also reassigned the teachers m

the system in compliance with Singleton v. Jackson Municipa_l

Separate School District, 419 F. 2d 1211, (5th Cir. 1969).

On July 23, 1970, the District Court approved such plan

and ordered it implemented for the opening of school foi the

1970-71 school year, declaring that the plan did, in law and in

fact, comply with all pertinent decisions of the United States

Supreme Court and this Court, eliminate all vestiges of the

dual system, and convert the East Baton Rouge Parish School

System to a unitary school system. (Record, Vol. 3, Pages

766- 773). No appeal was taker from this judgment b> an> part> .

The school system continued to operate successfully under

this plan until 1974 when plaintiff-intervenors, Bryant, et al .

filed a motion for further relief alleging the system was still

not unitary. (Record, Vol. 3, Pages 787-792). In considering

this motion, the District Court appointed outside experts, the

Louisiana Educational Laboratory, to study the school system

- 3-

and make findings and recommendations to the Court as to whether

the system had become unitary under its 1970 Order and was still

unitary. (Record, Vol. 3, Pages 854 and 855).

After a hearing on June 18, 1975 on all pending motions,

including the report of the court-appointed experts, the District

Court rendered judgment on August 21, 1975, finding that the

school system was still, in fact and in law, a unitary school

system. The Court therefore denied the motion of plaintiff-

intervenors and dismissed this litigation. (Record, \ol. 3,

Pages 944-956). Plaintiff appealed that judgment, and on

•\pril 7 , 1978, this Court issued an opinion and order vacating

the judgment of the District Court and remanding for further

consideration in light of this Court's opinion. 570 F. 2d 1260.

After remand, the United States was permitted to intervene

on behalf of plaintiffs. After requiring a report from the

School Board on the use of other "tools” of desegregation, trial

proceedings began with the Court entering an order declaring

this to be "complex litigation" under the rules and ordering

extensive pre-trial procedures. (Record, Vol. 4, Pages 1072-

10"6) . The Government then filed a typical cross-town bussing,

pairing, clustering, etc. plan which was adopted by plamtiff-

intervenors. (Record, Vol. 4, Pages 1091-1181, Government

Exhibit "7").

From May, 1980 through July, 1980, the parties were

involved in the extensive pre-trial and discovery procedures

required under the "complex litigation" rules. However, on

August 8, 1980, the United States filed a motion for partial

- 4 -

summary judgment on the issue of liability (non-unitariness)

and requested tv.e trial be held only on the issue of appropriate

relief. Cn September 11, 19S0, the District Court rendered

a partial summary judgment holding the school system to be

non-unitary with respect to student assignment, and ordering

the Board to submit a proposed plan for additional desegregation.

(Record, Vol. 4, Page; 1329-1344). Although the School Board

immediately noticed at appeal to this Court from that partial

summary judgment, it also immediately commenced good faith

compliance with the District Court's order to develop a plan

for further desegregation.

On September 11, IPSO, the District Court granted partial

summary judgment as to the School Beard's responsibility to furthe

desegregate this school system and ordered the School Beard to

submit a desegregation plan to the District Court by October Id ,

I 96 0 , barely one ".onth later, even though the School Board had

requested 120 days to prepare and submit its plan. Davis v. rast

Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 4 9S F. Supp. sSO (.4.D. La. 19Su)

(R, 1329- 1344).1 At the time of this order., the school system had

just employed a new Superintendent of Schools, Dr. Payment: G.

utnougr Dr. .rvesen hs d had p r i c: experie nee : t h - - £

systems 3rid school d esepi efea t ioi.., having beer, oup e r i n -

Schools in .Y , .Vmnesota,, he was net ther oughly

familiar with this school syste: L v i c u s 1 y ,

time to formulate a comprehensive cesegre^at

: e n; r e : e r sThe designation "R" followed b> a r-~- ------ —

sccutively paginated It-volume- reecre. References to the 2 volume

record in 80-3298 and the 4 volume record in 82-3412 are shown by

the designation S.R. plus the appeal number.

- 5 -

Utilizing his own prior experience with school desegregation

in Minneapolis and being aware of this school system's own previous

success with magnet schools, Dr. Arveson obtained School Board

approval to create a community advisory council, bi-racial in

nature and composed of citizens from all walks of life m the

community, for community input and to employ outside nationally

recognized experts in school desegregation.3 Superintendent

Arveson also created a desegregation task force composed of school

employees to assist in the gathering of necessary data, etc. to

1The nationally recognized experts m school de_eg:etati ,‘P •

by the Board was the firm of HGH, Inc. The principals of this

firm are Larry W . Hughes, William M. Gordon, and Lair> W . Hillman.

1arrv Hughes is a professor and the chairman of the Department of

AdninistratiorLand^Supervision at the University of Houston, Texas.

Dr? Hughes specialized in the personnel programing side of school

desegregation. William M. Gordon is a professor of education at

Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. He specialized m pupil assignment

and c u ^ z u l u m development. Larry K Hillman is a professor of

education at Wavne State University, Detroit. His specials i-

pupil transportation and metropolitan plan development.

Together the authors have been the principal designers or significant

contributors to over 75 desegregation pl.n*. 'oL

vere the architects of the plans submitted b> the State hoard or

Education of Ohio in the Cleveland and CoJu^ us cases. Tv e ha

served as experts in developing desegregation plans for the Unite

States in school cases in this state as well as el^ev.-ere. vne o

more of them recently participated in developing^ . c h S o f ^ t e m ) for

plan (very similar to the plan developed fo: 1 7 ^ 1 *

Chicago, Illinois, which has recently been appicveu b> the

States ar.d the District Court.

Although the principals in HGH Ino fanrliar^tth

K l S H S nandat oryDrea*s s i gnr.ent plans it U i zrngy h . » . l % of

same amount of desegregation without the evt, mental effect..

• 6 -

assist him and the outside experts in developing such plan.

The school system expended some $4000,000.00 in developing

its magnet school concept plan.

At the commencement of trial on the merits of the School

Board's plan on March 4, 1981, the District Court read a 16

page statement into the record. This statement warned the

parties, particularly the School Board, as to what the school

system would face at the opening of schools, indicated' the

Court was not satisfied with either the plan proposed by the

United States and plaintiff-intervenors or the plan proposed

by the School Board and ordered the parties to commence private

negotiations looking toward a consent decree with such negotia

tions to begin at 9:00 a.m. on Wednesday, March 11, 1981 and

continue through at least March 24, 1981. (R. 1590-1607).

These court-ordered, three-cornered negotiations continued

on an almost daily basis until April 15, 1981 when the parties

advised the Court that they were unable to reach agreement on

a preposed consent decree. On April 16, 1981, the Court issued

an order terminating such discussions.

A short 15 days later, on May 1, 1981, the District Court

issued its findings and conclusions rejecting both the School

Board's plan and the Government's plan and ordering its own

plan to be implemented. However, rather than taking the plan

preferred by the local school authorities and modifying it, or

granting the school authorities an opportunity to modify theii

-7-

plan to correct what the District Court perceived as

deficiencies, the Court basically adopted the mandatory

reassignment plan prepared by the Government’s expert,

including pairing, clustering, rezoning, and cross-town

busing, with modifications reducing a few of the longest

cross-town busing components, closing some schools, etc.

The Court's plan closed fifteen elementary school and

one high school. Of the sixteen middle schools (serving

grades 6-8), it converted fourteen of them to single-grade

centers and two of them to two-grade centers. It left six

predominantly white schools and seven predominantly black

schools. It paired and clustered (3 § 4 school clusters) all

of the remaining elementary schools. Some bus routes, due to

distance, heavy traffic, etc., are as long as twenty-five

miles and taking forty-five minutes to one hour in time, one

way. The Court's plan also required the removal of all temporary

classroom buildings (being utilized in order to alleviate over

crowding at particular schools) at the remaining few predominantly

one-race schools and established a maximum student capacity of

twenty-seven students per classroom. In at least one rapidly

growing residential area of the parish, this inability to admit

newly resident students has resulted in having to utilize one

sixty passenger school bus to transport only twelve students to

other schools with the bus route being approximately thirty-nine

miles long and taking one hour to complete.

-8-

The Court's plan also converted the school system's

middle schools (grades 6-8) to singel-grade centers. Under

this proposal, a child could go to five different schools

from the fifth to the ninth grade. Its effect would have

been absolutely disastrous. It was only after repeated

urging from Superintendent Arveson that the Court finally

approved, in part, a proposal maintaining the middle school

concept. The Board's proposal for middle schools would have

left one additional one-race school, Scotlandville Middle School

(adjacent to Scotlandville High School, which the Court had

closed as being too isolated to be desegregated). The Court

rejected that portion of the proposal, requiring Scotlandville

Middle School to remain open but ordering the School Board to

maintain an actual enrollment of at least 601 white and not

more than 401 black (order of May 7, 1982).

The Court's order directed implementation of its plan with

respect to elementary schools with the opening of schools in

August, 1981 with the provisions applying to the secondary

schools to be implemented with the opening of schools in August,

1982. Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 514 F. Supp.

869, 874 (M.D. La. 1981). The District Court (R. 2010-2011),

and this Court, denied the School Board's applications to stay

implementation of the plan. Implementation of the plan, even

after elimination of the single-grade centers, resulted in the

loss of approximately 4,000 students after one year and, after

two years, approximately 7,000 students.

-9-

The School Board and private plaintiff-intervenors

both noticed appeals from that judgment. The United States

did not. Those appeals (No. 81-3476 in this Court) have been

consolidated with the School Board's previous appeal (No.

80-3922 in this Court). The District Court, thereafter

continued to hear various motions filed by the parties and

continued to issue orders placing additional requirements on

the School Board. Some of these additional motions,.rulings,

etc. are found in the record in Volume V, Page 1620, and pro

ceeding through Volume VI and Volume VII of the record.

Since the record was completed and forwarded to this Court

as of October 31, 1981, the District Court has continued to

hold hearings on various matters and issue orders generally

placing other additional requirements on the School Board. The

School Board timely filed notices of appeal from those orders,

which are the subject of these consolidated appeals and this

brief.

Thereafter, on August 6, 1982, after approximately one year

of implementation of the Court's elementary school plan, the

United States filed in this Court a motion to stay further

proceedings in this appeal to afford the District Court an

opportunity to re-evaluate and modify its plan in light of actual

experience. That motion advised this Court that the United

States would prepare and provide for the District Court and

the parties an alternative to the Court's existing desegregation

-10-

plan. See Government Motion to Stay Further Proceedings

in this Court of August 6, 1982, Page 9. In that motion,

the United States 3lso stated that the District Court accurately

described the plan of their expert, Dr. Foster, as a "classic

pair 'em, cluster 'em, and bus 'em plan." Davis v. East Baton

Rouge Parish School Board, 514 F. Supp. 869, 873 (M.D. La. 1981).

The Government also in that motion labeled court-ordered

transportation "...generally to be a failed experiment...".

See Government Motion to Stay Further Proceedings in this Court

of August 6, 1982 at Page 3. On August 30, 1982, this Court

granted that motion.

In August, 1982, the United States retained another school

desegregation expert, Professor Christine Rossell of Boston

University to undertake a study of this school system and the

operation of the court-ordered desegregation plan. Dr. Rossell s

preliminary study confirmed the Board's assertion finding that

4,244 students had left the system since the year before the

Court's plan went into effect. See Brief of United States in

81-3476, Page 4 and Footnote 7.

On December 10, 1982, the United States filed with the

District Court and the parties its proposed alternative to the

District Court's plan "...designed to desegregate the public

schools in a more effective manner...." As stated by the

Government in its brief in 81-3476, at Page 5, the Rossell plan,

-11-

"...Rather than relying on mandatory assign

ment techniques ... employed educational

incentives to attract departing students

back to the system and achieve a level of

desegregation comparable to that sought by

the District Court. Under the Rossel plan,

desegregation was to be accomplished by court-

ordered school closings, by encouraging the

use of majority transfers and by magnet schools..."

In fact, the Rossell plan drew freely from, including specific

references to, the magnet school plan originally proposed by

the School Board.

Upon reviewing the proposed Rossell plan, Superintendent

Arveson and his staff and the School Board understood the

Rossell plan to be an alternative plan to be implemented in

lieu of the District Court's plan for the opening of schools

for the 1983-84 school year. Superintendent Arveson and his

staff also felt that the Rossell plan had considerable merit.

At present, the school system is completing its second

year under the Court's busing plan having lost approximately

7,000 students. Projections for next year indicate a loss of

another 1,100 students. That plan has been made even more

onerous by subsequent orders of the District Court, which are

the subject of these consolidated appeals. These appeals were

also included in the stay of proceedings in this Court requested

by the United States.

-12-

SUMMARY OF A R G U M E N T

The District Court's desegregation plan for this school

system is presently pending in this Court in consolidated

appeals Number 80-3922 and 81-3476. In those appeals, appellant

School Board contends that the District Court's plan far exceeds

any constitutional violation and, in fact, is designed to

achieve a racial balance in virtually every school in the system

contrary to constitutional requirements and the admonitions of

the Supreme Court in cases cited in argument.

However, not only did the District Court's plan seek to

achieve a racial balance, the District Court has continued to

issue supplemental orders at the District Court level which

clearly show his continued pursuit of racial balance at the

elementary school level, establish a flat racial quota of

60% white - 401 black at all magnet middle schools and all magnet

high schools, and also establishes a flat racial quota of 601

white - 40% black at one regular middle school. In addition,

the District Court's supplemental orders give discriminatory

preferential treatment to some students and holds the School

Board responsible for the "white flight" that has occurred since

the District Court's plan was ordered. The school system lost

approximately 4,000 students in the first year of implementation,

approximately 3,000 more in the second year of implementation,

and it appears we will lose approximately 1,000 more for the

coming school year.

-15-

Furthermore, the District Court has now established

a series of periodic status conferences (almost monthly)

during which the District Court involves itself in virtually

every facit of the operation of the school system.

Appellants respectfully submit that the supplemental

orders and actions of the District Court which are the subject

of this appeal, when added to the District Court's original

plan which is presently pending on appeal in this Court, paint

an absolutely clear picture of a district court whose original

desegregation plan improperly sought to achieve a racial balance

in virtually every school and which is now going even further

beyond the scope of its jurisdiction and authority with orders

designed to recreate and maintain that racial balance. Appellants

further submit that the District Court is involving itself in

the day-to-day operation of every facit of the school system to

an extent that is far beyond anything that the Supreme Court or

this Court has approved in any of the cases cited in argument.

In one of its early decisions, the District Court stated

that it did not want to become a "sidewalk superintendent",

he respectfully submit that that is exactly what the District

Court has now become.

Appellants also believe that the District Court's orders

assessing responsibility for "white flight" on the local School

Board, and the implications contained therein that a massive

reassignment of elementary school students may be necessary to reachieve a

-14-

racial balance, may very veil write the end of this school

system. Every decision of the Supreme Court and this Court

has clearly he]d that the local school authorities cannot

be held responsible for those parents and students who leave

the school system rather than submit to the Court's order,

In addition to the School Board having no power to stop such

flight, holding it responsible and requiring continual reassign

ment of students only penalizes those students who stayed with

the public school system and complied with the Court's order.

ARGUMENT'

I. WHAT DO THE SUPPLEMENTAL ORDERS OF THE DISTRICT COURT

REQUIRE AND WHAT IS THE LAW WITH RESPECT THERETO?

A. ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ASSIGNMENT

As indicated in brief in No. 81-3476, the School Board

contends that the District Court's May, 1981 desegregation

plan is improperly designed to achieve a racial balance _.n

virtually every school in the system. The supplemental orders

of the District Court, which are the subject of this brief,

reaffirm that pursuit of racial balance.

In its order of March 8, 1982, we find the District Court

saying with respect to the elementary schools,

"...It is apparent that some adjustment in

student assignment must be made in the

elementary schools for 1982. The Court

requests that the Superintendent and his

staff analyze the elementary school plan

and submit" suggestions for changes in student

assignments such that every elementary school

...will have a racial balance closely approxi-

matine the racial make-up of the school

system. This suggested plan must be predicated

upon the pairs and clusters set forth in the

Court's order of May 1, 1981, and must be^

submitted on or before March 29, 1982...."

(Emphasis added). [S.R. 82-3298, \ol. I,

Page 2216] .

Again, in the Court's order of August 30, 1982, we find the

District Court saying and requiring the following:

"...The School Board is hereby ORDERED to

assign kindergarten students for 1982-85,

next years first grade students, on a racial

composition assignment that reflects a

racial composition of the cluster..."

(Emphasis added). [S.R. 82-3412, Vol. II,

Page 2820] .

We respectfully submit that the above are not the orders of a

District Court seeking simply to meet the requirements of the

Constitution by eliminating discrimination and denial of equal

protection of the law, they are the orders of a District Court

seeking to achieve racial balance.

We respectfully submit that the pursuit of such racial

balance clearly goes far beyond the requirements of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and are directly

contrary to the holdings of the Supreme Court in Milliken v.

Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 94 S.Ct. 3112, 41 L.Ed.2d 1069 (1974)

that the aim of the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of equal

protection is to assure equal educational opportunity without

regard to race; it is not to achieve racial integration in

public schools and Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklinberg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554, that the

Constitution does not require any particular racial balance in

schools and district courts that attempt to achieve such racial

balance should be reversed. It would appear clear, that in

-16-

this school system, the District Court is attempting to do

exactly what the Supreme Court has repeatedly said it should

not do.

B. HOLDING SCHOOL BOARD RESPONSIBLE FOR FAILURE OF

ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PLAN DUE TO "WHITE FLIGHT"

When the District Court’s racial balancing, pairing

clustering, desegregation plan did not work , the District

Court immediately assessed the School Board with the responsi

bility for such failure. The District Court's determination

that its plan was not "working" was based upon the fact that

most of the formerly all black schools, which were paired and/or

clustered with formerly all white schools, such as Harding,

Progress, Ryan, Belfair, Eden Park, Dufrocq, and Buchanan, were

still predominantly black after his plan was implemented.

Although not mentioned in the District Court's supplemental

opinion and order, it is also a fact that many of the formerly

all white elementary schools, such as Audubon, Broadmoor,

LaSalle, and Goodwood have now also become either majority or

predominantly black. The supplemental opinion and order of the

District Court is found at S.R. 82-3412, Vol. II, Pages 2815-2823.

Although the District Court apparently recognized, at least

to some degree, that "white flight" was primarily responsible

for the previous all black elementary schools remaining predomi

nantly black (it is, of course, also primarily responsible for

the previous all white elementary schools becoming majority or

-17-

predominantly black), it assesses the blame and responsibility

therefor, by a strange and rather convulted reasoning process,

on the School Board. We respectfully suggest that the District

Court's reasoning is incorrect and that its assignment of the

responsibility for such "white flight" to the School Board is

contrary to the decisions of the Supreme Court, this Court, and

other courts of appeal.

The District Court begins its discussion of this problem

with what appears to be the incorrect assumption that when its

plan failed to eliminate previously all black elementary schools

due to "white flight", the School Board and/or the District

Court then had the responsibility of again reassigning the

remaining students by some method of assignment which would

hopefully create a racial balance in those schools. At Page

2816, we find the District Court beginning its discussion with

the following statement:

"...The continuing duty of the School Board

is, however, to desegregate the entire school

system and the 1981-82 effort left too many

black schools remaining at the elementary

level. The system is not desegregated until

there are no ’black' schools and no 'white'

schools, simply schools. It is this Court's

duty to call for additional remedial measures

where necessary...."

We would point out that the "1981-82 effort" of the School Board

was implementation of the District Court's pairing-clustering

plan.

Beginning on Page 2817 and continuing through Page 2820,

the Court below discusses the assignment procedure used by the

-18-

School Board for elementary students and by a rather strange

reasoning process, concludes that such procedure, and not

dissatisfaction of parents with the Court's plan, caused the

"white flight" and the resulting continued existence of pre

dominantly black schools. The Court first notes that it

granted the School Board permission to establish special schools,

such as a "fundamental school" or a "continuous progress school"

at one or more of the elementary schools contained in the Cojrt s

three and four school clusters. The School Board's purpose in

requesting permission to establish these special schools was to

give parents more options or choices in the hope that they \\ ould

remain with the school system in order for the Court s plan to

work.

Actually, the elementary student assignment procedure

utilized by the School Board was simple, computerized, correct,

logical, and virtually the only procedure that could be utilized

in assigning students to elementary school under the Court's

pairing-clustering plan. First, the School Board utilized as

its bank or pool of students available for assignment, all students

who attended the public elementary schools in grades K-5 for the

1980-81 school year. The Court's elementary school plan, which

was to be implemented for the 1981-82 school year was made public

on May 1, 1981. The survey of available elementary students and

the process of reassignment under the Court's plan commenced in

late May and June of 1981.

-19-

After ascertaining, through the computer, the names of

all aArailable elementary age students in the public school

system, the School Board sent forms to each student in each

cluster showing the three or four schools available to that

student under the Court's plan. Where a special "fundamental"

or "continuous progress" school had been established in a

cluster, the form gave the parents the option of listing their

first, second, and third choice of schools within their particular

cluster. This form went to the parents of every elementary

student who attended public schools the preceeding year, as the

School Board had no way of knowing that any of those students

would not attend public schools the following year under the

Court's plan.

This information was assembled on the basis of each three

school or four school cluster created by the Court's plan. A

breakdown of the number and/or percent of students in each

cluster who did and did not respond and submit a preference

form is as follows:

CLUSTER #1

Registration Forms

Not Returned

Total Number Percentage

in Cluster Not Returned

Eden Park

Audubon

Belfair

Broadmoor

175 1289 14%

CLUSTER #3

Brookstown

North Highlands

Delmont

195 1107 18%

-20-

CLUSTER #4

Registration Forms

Not Returned

Total Number

in Cluster

Percentage

Not Returned

Brownfields

Ryan

Tanglewood

188 1175 16%

CLUSTER #5

Buchanan

Highland

Magnolia Woods

112 830 13%

CLUSTER #6

LaSalle

Dufrocq

Cedarcrest-Southmoor

Goodwood

202 1275 16%

CLUSTER #8

LaBelle Aire

Glen Oaks Park

Forest Heights

Greenbrier

236 1642 14%

CLUSTER #9

Villa Del Rey

Howell Park

Greenville

Red Oaks

109 1285 8%

CLUSTER #10

Progress

Parkridge

Harding

White Hills

226 1366 17%

CLUSTER #12

Lanier

Merrydale

Park Forest

149 1305 11%

CLUSTER # 14

Westdale

Walnut Hills

Westminster

122 819 15%

-21-

The above information, with respect to each cluster,

was fed into the computer together with an additional factor

being the racial composition of that particular cluster as

mandated by the Court's order and the computer then randomly

selected students for assignment to particular schools based

upon the preference stated by the student subject to the limita

tion established by the racial balance quota established by

the Court's plan for each cluster. The racial balance or quota

for each school in the cluster was the paramount factor in such

assignments. This procedure resulted in each school in the

cluster having an assigned student enrollment of the approximate

racial composition of the cluster as a whole.

We respectfully suggest that the procedure utilized by the

School Board, as set forth above, is the only logical way to

assign students under the Court's plan, and that any school

system, or even any court, would have utilized the same procedure

under these circumstances. This procedure effectively assigned

to the elementary schools for the 1981-82 school year under the

Court's plan every student that we could reasonably expect to

attend the public schools.

However, when school opened for the 1981-82 school year

under the Court's plan in late August, white flight from the

Court's plan became apparent, as many of the previously all black

elementary schools remained predominantly black and some of the

previously all white elementary schools had become 50-50 or

majority white. At the present time, some of those previously

-22-

all white schools have now also become predominantly black.

The Court below, as indicated heretofore, immediately blamed

the School Board, and particularly its assignment procedure,

for the failure of the Court's plan to "work".

For example, at Page 3 of the Court's August 30, 1982

opinion and order (S.R. 82-3412, Vol. II, Page 2817) we find

the Court saying,

"...Most white parents who intended to send

their childred to East Baton Rouge Parish

Public Schools in 1981-82 stated their pre

ferences . Fewer black parents stated

preferences, but some did. Most white parents

who stated a preference chose location over

the program offered at the school. Few white

students chose formerly all black schools. A

significant number of white students submitted

no preference. This "no preference" group

included all students who had attended school

in 1980-81 but who had neither expressed a

choice, nor informed the school officials

that they would not return to school in 1981-82.

The white "no preference" group was composed in

great measure of those white students who had

either moved away or enrolled in private schools

Tor 1981-82.

All the names in the "pool" thus created,

were fed into the computer and "passes" were

made based upon first choice, second choice, and

third choice, depending upon the number of schools

in the cluster. Other factors, such as school

capacity and racial balance were also fed into

the computer. Most parents who stated a preference

received their first or second choice and the

formerly all white schools (most chosen by white

students) were pretty well filled on the first and

second "passes." That left the formerly all black

schools (least chosen by whites) to be filled on

the final "pass." Those unassigned until the last

"pass" included, as noted above, students who had

already left the school sys~tem but who had not

notified the School Board..77" (Emphasisadded).

-23-

The obvious problem with the Court's reasoning, as set

forth above, is that the School Board had no way of knowing

at the time it used its logical assignment procedure that the

students the Court refers to would not attend the public

school system. (The School Board did, in fact, eliminate

from the pool every student who indicated that they were not

returning to the school system the following year for whatever

reason). It is not at all unusual for the parents of many

students in a school system to fail to respond to this type of

survey or any other survey which a school system might conduct.

The District Court even admits the School Board could not

have known when it refers to "...students who had already left

the school system but who had not notified the School Board..."

As a matter of fact, even now, we do not know for sure how many

of the white students who have left the school system were in

the group who did not submit a preference as compared to the

group which did submit a preference but who were still not

satisfied with their assignment and the Court's plan.

For the School Board to have done what the Court apparently

implies they should have done, i.e., exclude from assignment all

students who did not submit the preference form and assign only

those students who did submit the preference form, could have

resulted in utter chaos at the opening of school in August, 1981

when all or most of those children showed up to attend school

without knowing to which school they had been assigned. No

-24-

school system can effectively operate on the basis of

assignment of only substantially less than its potential

number of students. Any professional educator and admini

strator will so testify, as did Superintendent Arveson.

Again, at Page 2818, we find the Court saying,

"...The School Boaid, the Superintendent and

the staff have insisted and, still insist,

to the court that the failure to desegregate

these black schools is the result of "white

flight," not the assignment procedure. The

fly in the ointment w ith that approach is

that the "white fT.Lght" (if, indeed, that

is what it was) occurred before, not after,

the assignments were madel By including In

the assignment "pool" the names of white

students who had already left the system and,

therefore indicated no preference of school,

the procedure used contaminated the results.

The assignment procedure utilized guaranteed

that the "undesirable" black schools would

remain black because most of the white students

assigned to them had already left the system..."

(Emphasis added).

Here again, the Court makes several incorrect assumptions.

First, he assumes that the "white flight" occurred before, not

after, the assignments were made. There is simply no evidence of that

in this record and the true fact probably is that no white flight

occurred prior to May 1, 1581, the date of the Court's order,

and what white flight did cccur probably continued throughout

the summer until the opening of schools in last August. Next,

the Court assumed that the only reason for many students not

returning the preference form was again that they had "...already

left the system...". Again, there is simply no evidence in this

record to support that conclusion. The probabilities are that

many white parents, like the many black parents who did not

-25-

submit preference forms, did so because they didn't care,

they didn't take time, they were looking forward to vacation

time with their children, and various other reasons including,

of course, that they would not continue their child in public

school under the Court's plan in any event.

On Page 2819, the District Court again makes a final

conclusion, unsupported by any evidence, that,

"...The assignment procedure utilized

guaranteed that the 'undesirable' black

schools would remain black because most

of the white students assigned to them had

already left the system... (Emphasis added).

Not only was there no evidence in the record to support the

District Court's assumptions and conclusions, we would respect

fully suggest that the evidence actually shows that the "assign

ment procedure" used by the School Board was not only logical,

but could have had, at best, only a minimal effect on the Court's

plan "not working".

For example, we would refer the Court to the figures set

forth heretofore with respect to the number of students and

percentage of students in each cluster who did not return

preference forms. The percentage of students not returning

preference forms in each cluster ranges from a low of 8% to a

maximum of only 18% for an average of only 14% for all clusters.

The total number of students in all ten clusters who did not

return preference forms is only 1,714. And, these percentages

and figures also include many black students who likewise did

-2 6-

not return the preference forms as noted by the District

Court in its opinion. Yet, in the first year of implementa

tion of the Court's plan, at the elementary school level only,

the school system lost approximately 4,000 students.

We respectfully suggest that these figures, and the facts,

make it absolutely clear that the District Court cannot, and

should not, blame the School Board for the failure of the

District Court's pairing-clustering-busing plan to "work".

The only time such a plan ever works is during the brief period

when someone is sitting down at a desk or library table working

with numbers on a sheet of paper. They never work on the ground

when the school system must transpose the numbers on the sheet

of paper to real children and their parents.

One might inquire - Of what moment is all of this? hhat

difference does it make as to whose fault it is that the Court s

plan did not work or the reason that the Court's plan did not

work? We respectfully submit that the answer is immediately

discernable and of the utmost importance.

First, the District Court's pairing-cluster-busing plan

which requires the cross-town busing of thousands of small

elementary school students away from their neighborhoods m the

pursuit of racial balance goes so far beyond the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution and decisions of

the Supreme Court with respect thereto, and is so far beyond

the proper function, jurisdiction, and authority of a District

-27-

Court under our federal system, that it should not be

countenanced. Such a plan is, in fact, contrary to the

holdings of the Supreme Court and in Milliken and Swann

cited heretofore.

In Swann, supra., the Supreme Court clearly and firmly

stated,

"...If we were to read the holding of the

District Court to require, as a matter of

substantive constitutional right, any parti

cular degree of racial balance or mixing,

that approach would be disapproved and we

would be obliged to reverse...." (28 L.Ed.2d

554 at 571) .

Although it is true that the District Court found some schools

to be too "racially isolated" to be desegregated, closing several

schools and allowing a few to remain open (at least temporarily)

as racially identifiable schools, it is clear that the District

Court's original May 1, 1981 plan was designed to acheive the

60-40 racial balance in all remaining schools. The supplemental

orders, which are the subject of these appeals, clearly reconfirm

that purpose and intent of the Court below.

However, these supplemental orders of the District Court

go far beyond, and are even contrary to, the Constitution and

holdings of the Supreme Court in another important respect.

They clearly hold the School Board responsible for white flight

over which the School Board has no control whatsoever. The

Constitution only prohibits and controls Government or state

action. The pertinent portion of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution on which this litigation is based, says only

that,

-28-

"AMENDMENT XIV. Section 1. ...No state

shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges or immunities of

citizens of the United States; nor shall

any state deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process

of law; nor deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws...." (Emphasis added).

The cases are legion that this amendment applies only to

the states and does not apply to private individual citizens.

The jurisprudence is also clear that neither the state

nor its agencies, i.e., this School Board, can be held responsible

for the discriminatory acts or conduct of private individual

citizens in school desegregation cases or otherwise. Dayton

Board of Education v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406, 53 L.Ed.2d 851,

97 S.Ct. 2766 (1977) (Dayton I); Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 61 L.Ed.2d 720, 99 S.Ct. 2971 (1979)

(Dayton II); Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S.

449, 61 L .Ed.2d 666, 99 S.Ct. 2941, reh den 62 L.Ed.2d 121, 100

S.Ct. 186 (1979); Austin Independent School District v. United

States, 429 U.S. 990, 50 L.Ed.2d 603, 97 S.Ct. 517 (1977);

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development

Corporation, 429 U.S. 252, 50 L.Ed.2d 450, 97 S.Ct. 555 (1977)

and City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 64 L.Ed.2d 47, 100

S.Ct. 1490 (1980). See also, Pasadena City Board of Education

v . Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 49 L.Ed.2d 599, 96 S.Ct. 2697 (1976);

United States v. Southpark Independent School District, 566 F.2d

1221 (5th Cir. 1978); United States v. Texas Educational Agency,

606 F .2d 518 (5th Cir. 1979); and Ross v. Houston Independent

School District, F.2d ___ (No. 81-2323, 5th Cir. Feb. 16,

1983).

-29-

As the Supreme Court said in P a s a d e n a , 49 L.Ed.2d 599

at 607-609,

"...The District Court apparently believed

it had authority to impose this requirement

even though subsequent changes to the racial

mix in the Pasadena schools might be caused

by factors for which the defendants could

not be considered responsible. Whatever may

have been the basis for such a belief in

1970, in Swann the Court cautioned that 'it

must be recognized that there are limits'

beyond which a court may not go in seeking

to dismantle a dual school system. Id. at

28 , 28 L .Ed.2d 554 , 91 S.Ct. 1267 ___ "

Or, as Mr. Justice Powell stated it in his concurring opinion

in Austin, supra., while discussing desegregative effect of

residential housing patterns,

"...Such residential patterns are typically

beyond the control of school authorities.

For example, discrimination in housing--

whether public or private--cannot be attri

buted to school authorities..." (Emphasis

added).

Obviously, the same reasoning would apply to the flight of

white students from the public schools to private schools,

which is likewise beyond the control of the School Board.

What is the likely practical result if the District Court

is permitted to continue to hold the School Board responsible

for the white flight which has occurred because of the District

Court's plan? Although the District Court has not yet ordered

a massive reassignment of the remaining elementary students

in the school system, he has clearly intimated that the Board

must devise a plan to do so with the clear implication that if

-50-

the Board does not, the District Court will. Another

reassignment of the remaining elementary students in this

school system would be catastrophic and would result, almost

immediately, in a virtually all black system.

As noted heretofore, in the District Court's order of

March 8, 1982 (S.R. 82-3298, Vol. I, Page 2216), we find the

Court saying,

"III. Elementary Schools

It is apparent that some adjustment in

student assignment must be made in the elem

entary schools for 1982. The court requests

that the Superintendent and his staff analyze

the elementary school plan and submit sugges

tions for changes in student assignments such

that every elementary school (excluding those

which the court indicated would remain as

one-race) will have a racial balance closely

approximating the racial make-up of the school

system. This suggested plan must be predicated

upon the pairs and clusters set forth in the

court's order of May 1, 1981, and must be sub

mitted on or before March 29 , 1982." (Emphasis added).

Again, in his order of April 30, 1982 (S.R. 82-3298, Vol. I,

Page 2335), we find the Court saying,

"...And additional changes in student assign

ments must be made, if necessary to achieve

elimination of the dual system....the court is

particularly concerned about student enrollment

at Ryan, Harding, Progress, Belfair, Delmont,

Eden Park, Dufrocq, and Buchanan Elementary

Schools. These former all black schools

continue to have black enrollments far out of

proportion to the ratio of the system as a

whole; they are, therefore, still perceived as

black schools....Tf the School Board, Superin

tendent and staff, fail to suggest remedial

measures, the responsibility will then fall on

the Court by default...." (Emphasis added).

- 31-

In its order of August 30, 1982, we again find the Court

contemplating reassignment of students when it says,

"...The utilization of the elementary assign

ment procedure must stop. Whether the Board

can factor a 'preference' or choice into

school assignment for future students

entering the system, depends upon whether

the Board can devise an assignment procedure

that will recognize parental choices but will

also desegregate the 'black' schools.

The court hereby refers this matter to

Special Master W. Lee Hargrave for further

consideration and the conducting of any

hearings that may be necessary to determine

an equitable and effective assignment procedure

for students entering the system in the future..."

(S.R. 82-3412, Vol. II, Page 2820).

Although the Court below has not yet ordered such a massive

reassignment of students, the implication is clear that it

intends to do so. The result of any such massive reassignment

would be disastrous and this Court must tell the District Court

that it has gone beyond its authority.

C. BATON ROUGE MAGNET HIGH SCHOOL RACIAL QUOTA

However, the Court below does not stop with merely general

assertions and requirements of achieving a racial balance in

the schools, it goes further and establishes a specific racial

quota iji two schools, namely, Scotlandville Middle School and

the Baton Rouge High Magnet School. The racial quota established

by the Court below is 601 white and 40% black, which was the

system-wide racial composition at the time the Court's desegre

gation plan was ordered. Prior to that time, the system-

wide racial composition had been approximately 65% white and

35% black. The present system-wide composition is approximately

50-50.

-32-

The Baton Rouge High Magnet School was the first

magnet school created by this School Board in 1972. It

has operated successfully since that time and is known to

be an excellent school offering exceptional educational

opportunities to students who qualify for admission. It has

received national attention, been visited by other school

systems, and only recently was selected as one of the finalists

schools in a nationwide competition for schools of excellence.

However, the District Court with a short one paragraph

minute entry order, establishes a discriminatory racial quota

for that school by providing that,

"...It is ordered that the magnet school

admissions policy now used by the School

Board is hereby modified so as to eliminate

that portion of the policy which permits

white student applicants to be admitted in

any proportion greater than 601 of the

total enrollment...." (Emphasis added).

(S.R. 82-5412, Vol. II, Page 2814).

The obvious question - Under such a quota system, what happens

to fairness and non-discrimination if 200 students apply

for admission and only 40 of them are black? Answer - 100 white

students are discriminated against because they happen to be

white and/or because black students did not choose to avail

themselves of this excellent educational opportunity. There is

simply no decision of the Supreme Court, of this Court, or any

other appellate court, much less the Constitution of the United

States, which permits the imposition of such discrimination and

denial of equal protection of the law by a United States District

Court.

-35-

D. SCOTLANDVILLE MIDDLE SCHOOL RACIAL QUOTA

The 601 white - 401 black racial quota established

for Scotlandville Middle School by the District Court's

order of April 30, 1982 (S.R. 82-3298, Vol. I, Page 2323

at 2331) is somewhat different from the Baton Rouge Magnet

High racial quota situation. First, Scotlandville Middle

School is not a magnet school requiring special qualifications

for eligibility for admission, it is simply a regular middle

school.

Secondly, the District Court's assignment plan for

Scotlandville Middle reassigned white students from the

Parkridge Subdivision immediately adjacent to the Baker Middle

School and bused them to Scotlandville Middle School. When

the white students did not show up at Scotlandville Middle

School because of having fled the school system to private

schools, the Court's 60-40 racial quota required the reassignment

and busing of approximately 150 black students from Scotlandville

Middle School in the northwest area of the parish to Broadmoor

Middle School and Southeast Middle School in the eastern and

southeastern portion of the parish.

Third, the District Court's order first penalized the

students who were assigned to, but did not attend, Scotlandville

Middle School by providing that such students could not,

"...Thereafter be accepted into the East Baton

Rouge Parish school system at any grade level

except upon specific authorization by the Court

after demonstrating to the Court that the reason

for not attending was unrelated to desegregation.

..." (S.R. 82-3298, Vol. I, Page 2332).

-34-

Fourth, that same order gave all students, black or white,

who attended Scotlandville Middle School for at least two

years, or for the 1982-83 school year only, a preference

over all other students in the school system "...to attend

Baton Rouge Magnet High School or (if established by the

Board) Scotlandville High Magnet School."

Although the District Court did, on its own motion,

recall its prohibition against the students ever returning

to the public school system at any grade level as not being

in keeping with the teaching of Valley v. Rapides Parish School

Board, 646 F.2d 925, 944 (5th Cir. 1981) and Pierce v. Society

of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, 45 S.Ct. 571, 69 L.Ed.2d 1070 (1925)

its order still maintains a discriminatory preference for

students who attend Scotlandville Middle School. This is a

particularly onerous provision in that it gives students who

attend Scotlandville Middle School a preference for magnet high

school admission over other students who stayed with the public

school system even though they were reassigned under the Court's

plan to some other desegregated middle school over their objections.

Several other factors are also worth noting with respect

to the 60-40 racial quota imposed at Scotlandville Middle School.

First, the District Court's May 1, 1981 plan closed Scotlandville

High School because the District Court found it too racially

isolated to be desegregated. Scotlandville Middle School is

located immediately adjacent to Scotlandville High School and the

same reasoning should have applied.

-35-

Secondly, no party to this litigation, nor any expert

employed by any party, suggested converting the school system’s

existing middle school concept (grades 6-8) to the single-grade

centers contained in the Court's plan. This was purely an

innovation dreamed up by the Court.

Superintendent Arveson immediately voiced strong objections

to this single-grade center plan and pointed out that it could

require a student to go to five schools in a five year period;

an elementary school in the fifth grade, a different sixth grade

center school, a different seventh grade center school, a

different eighth grade center school, and a different high school

for the ninth grade. He also pointed out to the Court that

another District Court in Louisiana had only recently, on May 19,

1980, issued an opinion and order which rejected and discontinued

a similar single-grade center plan. That order and opinion

(Honorable Tom Stagg, Judge presiding) stated at Page 4:

"...To desegregate the junior high and high

schools, the decree implemented a curious

change rule that turns students in certain

zones into 'mexican jumping beans . In some

cases, a student would be required to change

schools five times between the seventh and

twelfth grades..."

and,

"...The present plan, especially the multiple

annual school change of the Lee-Carroll-

Neville debacle is educationally unsound...

See CA No. 11,297 Andrews, et al. v. City of Monroe, et a h

consolidated with CA No. 12,171, Taylor, et al. u. Ouachita

Parish School Board, et al., including footnote 9 which shows

the rejected single-grade assignments.

-36-

Superintendent Arveson then filed a middle school plan

with the Court, which effectively desegregated every middle

school in substantially the same degree as the Court's single

grade center plan with the exception of Scorlandville Middle

School, which he felt was, like ScotlandvilLe High School,

too racially isolated to be desegregated. Part of the problem

with Scotlandville Middle School was that all of the surrounding

middle schools were already desegregated and assigning black

students from Scotlandville Middle School to those schools

while reassigning white students from those schools to Scotland

ville Middle School would have resulted in those schools becoming

majority or predominantly black as well.

Although the United States admitted in its response that

the middle school concept was a constitutionally viable method

of desegregating the middle schools, it suggested that Superin

tendent Arveson's plan be modified by closing Park Forest Middle

School. This proposal was unacceptable because Park Forest is

one of the larger middle schools, is a relatively new school

and possible the finest middle school faciLity in the system.

Furthermore, under Superintendent Arveson's plan it was already

thoroughly desegregated. The District Court rejected Superinten

dent Arveson's middle school proposal.

Thereafter, the School Board wrestled with the problem of

finding a way to successfully desegregate Scotlandville Middle

School, but was unable to reach a concensus. It did, however,

- 3 7 -

direct Superintendent Arveson to submit various alternatives

which had been considered, some suggested by parent groups,

to the Court for its consideration. The District Court also

rejected these proposals. (S.R. 82-3298, Vol. I, Page 2203).

At a subsequent status conference, the Court suggested

that further discussion with respect to the middle schools

might prove fruitful and a series of such discussions were

subsequently held between Superintendent Arveson and undersigned

counsel with counsel for the Justice Department, the United

States Attorney, and counsel for private plaintiffs. During the

last of these discussion sessions, considerable attention was

given to the possibility of placing a magnet component at

Scotlandville Middle School. The parties then reported their

progress to the Court and during such discussion, Superintendent

Arveson agreed, due to the short time before opening of schools

and implementation of the secondary school plan, to provide the

United States and private plaintiffs with a specific magnet

component for Scotlandville Middle School the next day.

The United States responded a few days later requesting

extensive additional specific information which would have been

virtually impossible for Superintendent Arveson and his staff

to provide in the short time available. However, any possibility

of agreement and consent decree with respect to middle schools

was eliminated a few days later when private plaintiffs advised

the Board that they would not agree to any revision of the

-38-

Court's May 1, 1981 order with respect to middle schools

unless the School Board would agree to

(a) Close Park Forest Middle School

(f) Dismiss its pending appeals

The Court then issued its order of March 8, 1982 rejecting

the School Board's middle school proposal.

Superintendent Arveson then made one last effort to

save the middle school concept by using three ethnic groups

to desegregate Scotlandville Middle School. As indicated

heretofore, Superintendent Arveson's original plan for the

middle schools successfully desegregated all of the middle

schools with substantially the same student body racial compo

sition as the Court's single-grade centers, except for Scotland-

ville Middle School. The problem with Scotlandville Middle

School was that if you reassigned black students from Scotlandville

Middle to the other surrounding middle schools and reassigned

white students from those schools to Scotlandville Middle School,

the racial composition of the other middle schools would have

passed the "tipping point" and become majority black and later

predominantly black or all black.

Dr. Arveson's final alternative plan was designed to maintain

a workable racial composition at the other middle schools by

reassigning some white students into Scotlandville Middle School,

some black students out of Scotlandville Middle School, and add

a third ethnic group, Vietnamese students by adding to the

curriculum at Scotlandville Middle a strong special English

-39-

language component for the Vietnamese students. The School

Board supported this proposal and it was filed with the

Court on March 30, 1982. (S.R. 82-3298, Vol. I, Page 2246).

The United States responded to this proposal stating that

they neither affirmatively supported or opposed this latest

proposal. However, they did indicate and suggested to the

Court, that other alternatives which the parties had discussed

and "...more specifically, the plan developed by Superintendent

Arveson, which included the magnet school proposal for Scotland-

ville Middle School..." would be preferable. (S.R. 82-3298,

Vol. I, Pages 2299 and 2300).

By order issued April 30, 1982, the District Court also

rejected this latest proposal by Superintendent Arveson and

the School Board while ignoring the Government's recommendation

with respect to the Scotlandville Magnet School program. Although

the Court did finally accede to Superintendnet Arveson's strong

and continuing plea for abandonment of the Court's single-grade

centers in favor of the middle school concept, it modified,

without recommendation from any party, Superintendent Arveson's

middle school proposal with what the Court referred to as "minor

modifications". These "minor modifications" however, reassigned

black students out of Scotlandville Middle School into surrounding

middle schools and reassigned white students out of the surrounding

middle schools into Scotlandville Middle School which, though

resulting in Scotlandville Middle School being only 38-a black,

made Baker Middle School 531 black and Northwestern Middle School

521 black.

-40-

These "minor modifications" also took white students

from Parkridge Subdivision, which is immediately adjacent

to Baker Middle School and reassigned them a considerable

bus ride away to Scotlandville Middle School. This order

also, as mentioned heretofore, established the 60-40 racial

quota at Scotlandville Middle School providing that,

"...The School Board is further ORDERED

to maintain the actual enrollment at Scot

landville Middle School at least 601 white;

conversely, this means that the actual black

enrollment shall not exceed 40%...."

Why not the same 60-40 racial quota for Baker Middle SchooL

and Northwestern Middle School? This order also prohibited

any student assigned to Scotlandville Middle School who did not

attend from ever again attending public schools at any grade

(this provision was later recalled by the Court on its own

motion as being not in accordance with the teaching of Valley v .

Rapides Parish School Board, supra.) and established an absolute

preference for admission to any magnet high school for any

student who attended Scotlandville Middle School for two years

or who attended Scotlandville Middle School during the 1982-83

school year. (S.R. 82-3298, Vol. I, Pages 2323-2336 at 2331 and

2332) .

On May 7, 1982, the District Court issued another supplemental

and amending order reaffirming its 60-40 racial quota at Scotland

ville Middle School and requiring the Board to report within

ten days after the beginning of the school term if the racial

-41-

quota at Scotlandville Middle School had not been met

and was becoming racially identifiable. (S.R. 82-3298,

Vol. I, Page 2341).

During the summer preceeding the beginning of the

1982-83 school year, the Board and Superintendent Arveson,

in good faith, prepared for implementation of the District

Court's secondary school plan, including assigning students

to Scotlandville Middle School exactly as ordered by the Court.

Of course, there is no way for any school system to know what

the actual enrollment at any school will be until the school

year begins and students actually appear at such school for

registration and attendance. In the case of Scotlandville

Middle School, a substantial proportion of the white students

reassigned from other middle schools to Scotlandville, left

the public school system for private schools, etc., and did

not attend Scotlandville when school opened.

Shortly after school opened for the 1982-83 school year,

on September 21, 1982, the School Board filed the report

required by the Court's previous order as to whether or not

it had achieved the racial balance or racial quota of 60% white -

401 black, at Scotlandville Middle School. This report indicated