Hill v. Franklin County Board of Education Brief for Intervening Plaintiff-Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hill v. Franklin County Board of Education Brief for Intervening Plaintiff-Appellee, 1966. d9e0833c-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c56ebb82-5352-40fc-b32e-9e9550a865f3/hill-v-franklin-county-board-of-education-brief-for-intervening-plaintiff-appellee. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

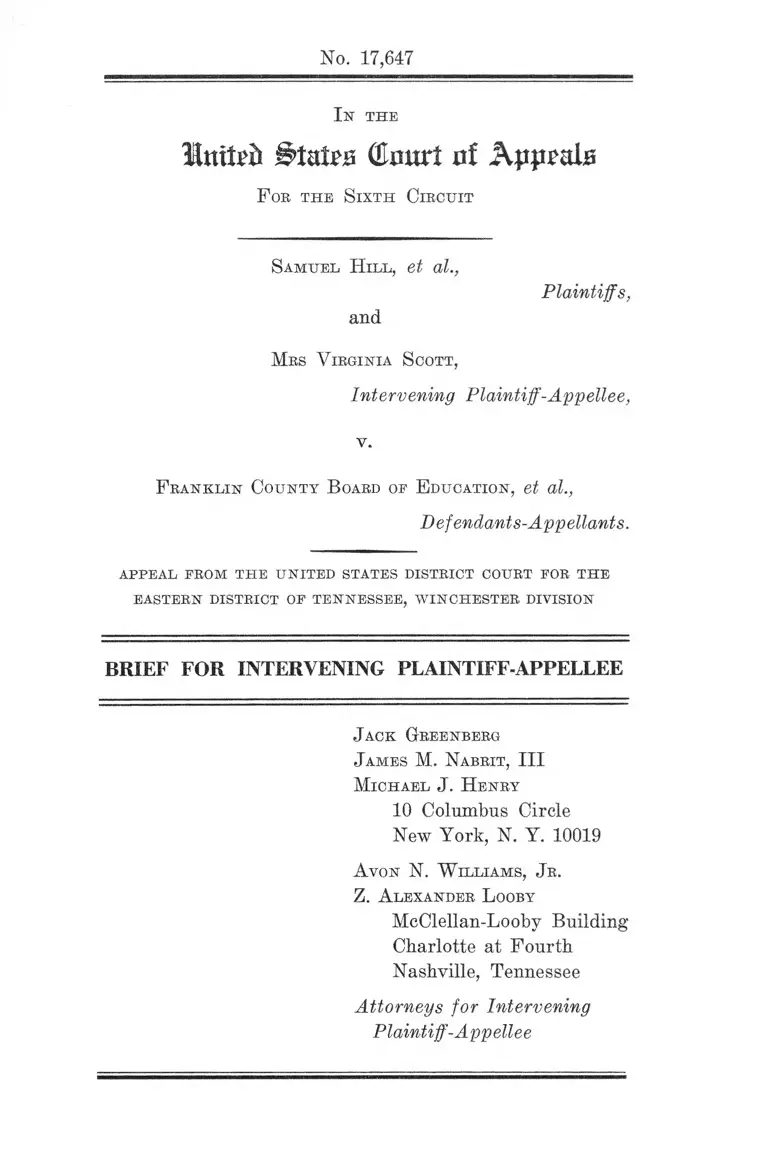

N o. 17,647

In the

Imfrii But?# Court of Appraio

F oe the S ixth Circuit

Samuel H ill, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

and

Mrs V irginia S cott,

Intervening Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

F ranklin County B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

appeal from the united states district court for the

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, WINCHESTER DIVISION

BRIEF FOR INTERVENING PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Michael J . H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Intervening

Plaintiff-Appellee

I.

Was the trial court justified in concluding that a Negro

faculty member was wrongfully discharged because of

race, when she had been assigned to an all-Negro school

on the basis of race and was discharged in consequence

of an enrollment loss at that school resulting from the im

plementation of a plan of desegregation, without compari

son to other faculty members in the system!

The District Court answered this question “Yes” and

Appellee agrees that it should have been answered “Yes.”

II.

Was the trial court within its allowable discretion in

awarding attorneys’ fees to a Negro faculty member who

had been discharged because of race, where there had been a

long history of discriminatory conduct on the part of the

board of education, and the bringing of the action should

have been unnecessary!

The District Court answered this question “Yes” and

Appellee agrees that it should have been answered “Yes.”

Counter-Statement o f Questions Involved

I N D E X

PAGE

Counter-Statement of Questions Involved ..... Preface

Counter-Statement of Facts ....................................... 1

Argument ....................................................................... 5

Question I ........................... 5

Question II ...................................... 13

Belief ........ 16

T able op Cases:

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) ........................ 10

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia,

321 F.2d 494 (4th Cir., 1963) ............................... 13,15

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965) ........................................................ 8,11

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 345

F.2d 310 (4th Cir., 1965) .....................................8,14,15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .... 9

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir., 1966) ............................. 7, 9,10

Clark et al. v. Board of Education of Little Rock

School District, 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir., 1966) ........ 14

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Comm’n v. Continental

Air Lines, Inc., 372 U.S. 714 (1963) ...................... 11

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) ............... 10

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, 360

F.2d 325 (4th Cir., 1966) 8,9

11

PAGE

Hill v. County Board of Education of Franklin County,

Tenn., D.C. Tenn. (1964), 232 F. Supp. 671, 673 ..... 13

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir., 1966) ...... 10

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jack-

son, Tenn., 244 F. Supp. 353 (D.C.W.D., Tenn.,

1965) .......................................................................... 16

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) .................... 10

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) ............................ 10

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) .......................... 11

Rolas v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 186 F.2d 473 (4th

Cir., 1951) .................................................................. 16

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School Dis

trict No. 32, 365 F.2d 771 (8th Cir., 1966) ............. 10

State ex rel Anderson v. Brand, 303 U.S. 95 (1938) .... 8

Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee of the Steel

Workers of Chicago, 223 F. Supp. 12 (N.D. 111.,

1963) .......................................................................... 8

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75 (1947) 11

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 346 F.2d

768 (4th Cir., 1965) ........ 9

Wieman v. Updegratf, 344 U.S. 183 (1952) ................ .8,11

Other A uthorities:

6 Moore’s Federal Practice (2nd Ed.) ........

Note, 77 Ilarv. L. Rev. 1135 (1964) ............

1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000 e-5(g)

. 16

. 15

.8,11

In the

Initeii Olmurt of Appals

F oe th e S ixth Ciectjit

No. 17,647

S amuel H ill, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

and

Mbs V irginia S cott,

Intervening Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

F ranklin County B oard op E ducation, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

appeal prom the united states district court for the

EASTERN DISTRICT OP TENNESSEE, WINCHESTER DIVISION

BRIEF FOR INTERVENING PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE

Counter-Statement of Facts*

This is an action in which Mrs. Virginia Scott inter

vened on behalf of herself and all other persons similarly

* This ease is one of three appeals—Nos. 17,647, 17,648, and 17,649—

arising from the same Motion for Further Relief and District Court

opinion. The respective parties have stipulated to file a Joint Appendix

under this Court’s Rule 16(5), which will not be printed until after

briefs are filed as provided by that rule. Thus the citations in this State

ment of Facts are to the typewritten transcript, and other papers in the

original record on appeal, rather than to the printed record.

2

situated, against the County Board of Education of Frank

lin County, Tennessee, seeking relief against the hoard’s

policy and practice of racially discriminatory discharges

of Negro teachers.

Mrs. Virginia Scott had approximately 29 years of teach

ing experience, 20 of which were in the Franklin County

school system (Tr. 13). She had taught at Mr. Zion elemen

tary school during all those 20 years (Tr. 13). Mt. Zion

was an all-Negro school, completely segregated as to faculty

and student body during that entire period (Tr. 14, 138).

Mrs. Scott was certified to teach grades one through nine

(Tr. 23). She had never received a reprimand or any other

such action reflecting on her ability as a teacher during all

those 20 years (Tr. 17, 136).

The Franklin County school system was ordered to adopt

a freedom-of-choice desegregation plan by the district court

in April, 1965. It is incorrect to state, as did appellants in

their brief, that desegregation was undertaken voluntarily

by the Franklin County school system. It resulted from

very long court litigation by plaintiffs in this case. Fur

thermore, it was the unwavering policy of the Franklin

County school system to assign Negro teachers only to

schools with exclusively Negro student bodies, through the

school year 1965-66, even though required to integrate the

faculty under the Court-ordered plan of desegregation of

April, 1965 (Tr. 166).

In August, 1965, when Mt. Zion School opened under

the new desegregation plan, the enrollment dropped from

approximately 80 to approximately 40 students, as a num

ber of the Negro students elected to transfer to the pre

viously all-white Huntland elementary school, which they

were now permitted to do under the new desegregation

plan (Tr. 15-16). Immediately after this enrollment loss

3

became apparent, on August 17, 1965 (Tr. 42) the Super

intendent sent Mrs. Scott a letter stating that due to the

drop in enrollment she was discharged (Tr. 17). Mrs.

Scott lacked the protection of the Tennessee teacher tenure

law, because she had not completed her higher education.

The two other teachers at Mt. Zion enjoyed tenure, so that

when the enrollment dropped the school system determined

to discharge Mrs. Scott (Tr. 141-142).

At a special session of the board of education immedi

ately thereafter, on August 23, 1965, the board voted unani

mously to ratify the Superintendent’s dismissal of Mrs.

Scott (Tr. 115-116). There was no attempt made at this

meeting to compare Mrs. Scott’s qualifications with any

other teachers in the system, except the other two at Mt.

Zion, before discharging her (Tr. 116-117). The Superin

tendent admitted that Mrs. Scott was singled out in the

discussion about teachers who lacked tenure, and that other

teachers who also lacked tenure were not discussed (Tr.

117, 137). The system in fact maintained no formalized

standards for determining which teachers to remove (Tr.

139).

Mt. Zion and Huntland Schools opened approximately

two weeks earlier than the other schools in the county

in order to permit a recess later during the cotton picking

season (Tr. 16). Thus, at the time that Mrs. Scott was

discharged, five days after the opening of the Mt. Zion

School, she could have been considered for any other

elementary school in the county without interfering with

an already in-progress session (Tr. 38).

Four other Negro teachers were discharged at approxi

mately the same time as Mrs. Scott in consequence of

enrollment losses at Negro schools resulting from the im

plementation of the plan of desegregation (Tr. 50).

4

At the same time that the Franklin County School Sys

tem discharged Mrs. Scott in consequence of the imple

mentation of the desegregation plan, there were 32 white

teachers in the system who also did not have degrees, as

Mrs. Scott did not (Tr. 127). Twenty-five of those were

junior to Mrs. Scott in length of service in the Franklin

County School System, and 27 of those had less total teach

ing experience than Mrs. Scott (Tr. 128). Twenty-three of

the 25 juniors in service to Mrs. Scott also had fewer col

lege credits than she did (Tr. 128). Four of these teachers

were employed for elementary positions in 1964-65, just

the year before Mrs. Scott’s discharge (Tr. 128). One of

these four teachers had been employed at the Huntland

Elementary School, the larger and previously all-white

school near to Mt. Zion (where Mrs. Scott had been teach

ing) to which the Negro students at Mt. Zion transferred

(Tr. 133). Mrs. Scott’s qualifications were compared to

none of these before she was discharged (Tr. 147-149).

Furthermore, just five days before Mrs. Scott was dis

charged, 15 new white elementary teachers were employed

by the system. None of these had anywhere near Mrs.

Scott’s experience (Tr. 150-151, 188-190).

The District Court held a hearing in this case on August

25, 1966, and filed an opinion on September 30, 1966.

The court found that the discharge of Mrs. Scott was

wrongful because based upon race. It is totally inac

curate to state, as did appellants in their brief, that the

“Trial Court denied all relief sought” except for a ten-

day period. The court found for the appellee, Mrs. Scott,

on the primary issue of wrongful discharge, and then

simply ruled that she had failed to mitigate her damages

by not accepting a subsequently offered position.

5

A R G U M E N T

I.

Was the trial court justified in concluding that a

Negro faculty member was wrongfully discharged be

cause o f race, when she had been assigned to an all-

Negro school on the basis o f race and was discharged

in consequence o f an enrollment loss at that school re

sulting from the im plem entation o f a plan o f desegre

gation, without comparison to other faculty members

in the system?

The District Court answered this question “ Yes”

and Appellee agrees that it should have been answered

“Yes.”

In this case, a board of education which was implement

ing a Constitutionally required plan of desegregation, uti

lizing the “freedom of choice” approach, discharged several

Negro teachers at previously all-Negro schools upon a sub

stantial drop in enrollment at those schools—without com

paring the qualifications of the discharged teachers to other

teachers in the system, and shortly after employing fifteen

new white elementary teachers for the system.

The “freedom of choice” desegregation plan had been

adopted under court order in April, 1965. At approxi

mately the same time, the school system made contracts

and assignments of faculty members for the following

(1965-66) school year. In spite of the court-ordered plan

of desegregation, the school system continued its unwaver

ing policy of assigning Negro teachers only to schools with

exclusively Negro student bodies for the 1965-66 school

year.

6

Appellee Mrs. Virginia Scott had been teaching for 20

years in the Franklin County school system, and had been

assigned to the all-Negro Mt. Zion Elementary School dur

ing that entire period. As the desegregation plan was im

plemented at the opening of the 1965-66 school year in

August 1965, an enrollment drop occurred at the Mt. Zion

School as a substantial number of Negro students trans

ferred to a nearby previously all-white elementary school.

Mrs. Scott was discharged from her position as soon as the

enrollment loss became apparent, since she was the only

non-tenure teacher at Mr. Zion.

In spite of the fact that Mrs. Scott was certified to teach

grades one through nine, her qualifications were not com

pared to those of any other teachers in the system apart

from the other two teachers at the Mt. Zion School, who

were both tenure teachers. The Franklin County school

system had no formal standards at that time for determin

ing which teachers must be discharged when enrollment

dropped below the state minimums for financial aid. At

the time of Mrs. Scott’s discharge, there were 32 white

teachers in the system who also did not have degrees and

therefore lacked the protection of the tenure law. Twenty-

five of these were junior to Mrs. Scott in length of ser

vice in the system, and 27 had less total teaching experience

than she did.

Just five days before Mrs. Scott was discharged, 15 new

white elementary teachers had been employed by the sys

tem—none of whom had anywhere near Mrs. Scott’s ex

perience. Furthermore, four other Negro teachers were

discharged at approximately the same time as Mrs. Scott

in consequence of enrollment losses at Negro schools result

ing from the implementation of the plan of desegregation.

While these teachers eventually obtained other equivalent

7

positions from the system, this was not until after all of

the discharged teachers had contacted an attorney to un

dertake litigation, and the State Commissioner of Educa

tion had intervened on their behalf, since they were tenure

teachers (Tr. 163-165). The subsequent offer to Mrs.

Scott, to which appellants refer in their brief, also oc

curred after these events.

Based upon these facts, the District Court concluded:

However, neither did the defendants have in effect

any standards of employment and dismissal by which

it could be properly determined whether Mrs. Scott or

some other teacher in the system should be discharged.

The Court finds that Mrs. Scott was dismissed simply

because she was the only non-tenure teacher at Mt. Zion

School. She was qualified and certified to teach any

and all grades one through nine. Five non-tenure

teachers with less experience than Mrs. Scott were then

teaching at Huntland School, although two of these

teachers were college graduates, and Mrs. Scott was

not. Four of the Huntland teachers were teaching the

same grades as Mrs. Scott.

Because the defendant Board had no definite ob

jective standards for the employment and retention

of teachers which were applied to all teachers alike in

a manner compatible with the requirements of the due

process and equal clauses of the Federal Constitution,

Chambers v. The Hendersonville City Board of Educa

tion, C.A. 4th (1966), ----- F.(2d) ----- [No. 10,379,

decided on June 10, 1966], and only compared with

Mrs. Scott’s qualifications those of two other Negro

teachers at Mt. Zion when deciding which teacher

should be dismissed, the cancellation of Mrs. Scott’s

teaching contract was wrongful.

8

The District Court’s decision is clearly in accord with the

now unarguable proposition that Negro faculty members

assigned to Negro schools on the basis of race may not be

dismissed in consequence of enrollment losses resulting

from the implementation of plans of desegregation, without

comparison to other faculty members in the system, since

such dismissals are clearly on the basis of race. In Frank

lin v. County School Board of Giles County (Va.), 360 F,2d

325 (4th Cir., 1966), the school board simply closed the

Negro schools, allowing all of the Negro children to trans

fer to the formerly white schools, but discharging all of the

Negro faculty members. The Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit held that on the record in the Franklin case,

no comparative evaluation of the discharged teachers with

the other teachers in the system had apparently been made,

and that therefore “the plaintiffs were discharged be

cause of their race.” 360 F.2d at 327. The Court said:

The defendants have conceded that the Fourteenth

Amendment forbids discrimination on account of race

by a public school system with respect to the employ

ment of teachers. Bradley v. School Board, 345 F.2d

310, 316 (4 Cir. 1965), reversed on other grounds, 382

U.S. 103 (1965).

Under the circumstances, the plaintiffs are entitled

to a mandatory injunction requiring their reinstate

ment. See: State ex rel Anderson v. Brand, 303 U.S.

95 (1938); Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952);

Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee of the Steel

Workers of Chicago, 223 F.Supp. 12 (N.D. 111. 1963).

We think the provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

(42 U.S.C. § 2000 e-5(g)) where the courts are granted

authority to order reinstatement of discriminitees fur

ther supports our conclusion. 360 F.2d at 327.

9

In Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education

(N. Car.), 364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir., 1966), at the end of a

school year the Negro enrollment in the system dropped

by 50% because Negro students who had attended the city

schools from adjoining counties were integrated into their

respective county schools, and the city board of education

then integrated its remaining Negro students into its

system, thereby reducing the number of teaching positions

by five. Of the 24 Negro teachers in the system, only

8 were offered re-employment for the following year,

although every white teacher who indicated the desire was

re-employed together with 14 new white teachers, all with

out previous experience. All of the Negro teachers were

required to stand comparison not only with all of the other

teachers previously in the system, but with all of the new

white applicants, before retaining their jobs, while none

of the white teachers was subjected to this test. The

Fourth Circuit said:

Patent upon the face of this record is the erroneous

premise that when the 217 Negro pupils departed

and the all Negro consolidated school was abolished,

the Negro teachers lost their jobs and that they, there

fore, stood in the position of new applicants. The

Board’s conduct involved four errors of law. First,

the mandate of Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954), forbids the consideration of race in

faculty selection just as it forbids it in pupil place

ment. See Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Educa

tion, 346 F.2d 768, 773 (4 Cir. 1965). Thus the reduc

tion in the number of Negro pupils did not justify a

corresponding reduction in the number of Negro teach

ers. Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

360 F.2d 325 (4 Cir. 1966). Second, the Negro school

teachers were public employes who could not be dis

10

criminated against on account of their race with respect

to their retention in the system. Johnson v. Branch,

364 F.2d 177 (4 Cir. 1966), and cases therein cited,

wherein the court discussed the North Carolina law

respecting teacher contracts and the right of renewal.

White teachers who met the minimum standards and

desired to retain their jobs were not required to stand

comparison with new applicants or with other teachers

in the system. Consequently the Negro teachers who

desired to remain should not have been put to such

a test. 364 F.2d at 192.

* • #

Finally, the test itself was too subjective to with

stand scrutiny in the face of the long history of racial

discrimination in the community and the failure of the

public school system to desegregate in compliance with

the mandate of Brown until forced to do so by litiga

tion. In this background, the sudden disproportionate

decimation in the ranks of the Negro teachers did raise

an inference of discrimination which thrust upon the

School Board the burden of justifying its conduct by

clear and convincing evidence. Innumerable eases have

clearly established the principle that under circum

stances such as this where a history of racial discrimi

nation exists, the burden of proof has been thrown upon

the party having the power to produce the facts. In the

field of jury discrimination see: Eubanks v. Louisiana,

356 U.S. 584 (1958); Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85

(1955); Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953); Norris

v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935). 364 F.2d at 192-193.

In Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School

District No. 32 (Ark.), 365 F.2d 771 (8th Cir., 1966), the

school board “re-elected” the Negro faculty members to

11

the Negro school but without signing contracts with them

at that time, and also adopted a “freedom of choice” de

segregation plan at about the same time for compliance

with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Upon ascertaining that

the enrollment was going to drop precipitously at the Negro

school, the board decided to close the Negro school alto

gether and completely integrate the system, and then in

formed all of the Negro teachers at the Negro school

that their jobs were abolished. Shortly thereafter, 13

teachers resigned or retired during the course of the sum

mer, and 14 new teachers were hired, 12 of whom were

white. The Board said that it simply applied its traditional

policy in cases of the closing of schools due to consolida

tion, namely, to absorb the teachers of the closed school

into the remaining schools if this could be done without

displacement of other teachers and, if not, to dismiss the

former. The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit said:

It is our firm conclusion that the reach of the Brown

decisions, although they specifically concerned only

pupil discrimination, clearly extends to the proscrip

tion of the employment and assignment of public school

teachers on a racial basis. Cf. United Public Workers

v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75, 100, 67 S.Ct. 556, 91 L.Ed. 754

(1947); Wiem-an v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183, 191-192,

73 S.Ct. 215, 97 L.Ed. 216 (1952). See Colorado Anti-

Discrimination Comm’n v. Continental Air Lines, Inc.,

372 U.S. 714, 721, 83 S.Ct. 1022, 10 L.Ed.2d 84 (1963).

This is particularly evident from the Supreme Court’s

positive indications that nondiscriminatory allocation

of faculty is indispensable to the validity of a desegre

gation plan. Bradley v. School Board, supra; Rogers

v. Paul, supra. . . .

We recognize the force of the Board’s position

that the discharge of the Sullivan staff upon the

12

school’s closing was only consistent with the action

taken by the Board in connection with eleven other

school consolidations, and consequent closings, in the

past. This stands in contrast to the past practice

noted in Franklin v. County School Bd., supra, p. 326

of 360 F.2d. And we need not now determine whether

across-the-board staff dismissals in the absence of

vacancies when a school is closed, and the failure

comparatively to evaluate the qualifications of those

dismissed with the qualifications of those retained,

standing alone and apart from racial considerations,

amount to an unconstitutional selection method. . . .

But on this record these dismissals do not stand

alone. This Board maintained a segregated school

system for more than a decade after its unconstitu

tionality was known and before it implemented a plan

to desegregate. The employment and assignment of

teachers during this period were based on race. . . .

The use of the freedom-of-choice plan, associated with

the fact of a new high school plant, produced a result

which the superintendent must have anticipated, de

spite his testimony that he “rather guessed” that Sulli

van would continue to operate; . . . All this reveals

that the Sullivan teachers did indeed owe their dis

missals in a very real sense to improper racial consid

erations. The dismissals were a foreseeable conse

quence of the Board’s somewhat belated effort to bring

the school system into conformity with constitutional

principles as enunciated by the Supreme Court of the

United States. 365 F.2d at 778-779.

13

II.

Was the trial court within its allowable discretion in

awarding attorneys’ fees to a Negro faculty member

who had been discharged because o f race, where there

had been a long history o f discriminatory conduct on

the part o f the board o f education, and the bringing

o f the action should have been unnecessary?

The District Court answered this question “Yes”

and Appellee agrees that it should have been answered

“Yes.”

The District Court said:

The Court further finds and concludes that the de

fendants have been guilty of “* * * a long-continued

pattern of evasion and obstruction * * *” of the de

segregation of the public schools of Franklin County,

Tennessee. In such event, it is an abuse of judicial

discretion for this Court not to award attorney’s fees

as a part of the costs. Bell v. School Board of Pow

hatan County, Virginia, C.A. 4th (1963), 321 F. (2d)

494.

* # #

In addition, although there has been marked im

provement, see memorandum opinion and order of

April 17, 1965, the Court is not yet convinced that the

defendants are exercising the desired degree of good

faith in transforming the Franklin County school sys

tem from a segregated to a nonsegregated system. Cf.

Hill v. County Board of Education of Franklin County,

Tenn., D. C. Tenn. (1964), 232 F. Supp. 671, 673. The

Court is of the candid opinion that, had it not been

for the delegation of an important facet of the duties

of the defendant board to its respective members with

14

in their districts, and had there been extant the re

quired good faith implementation of its present deseg

regation plan, Mrs. Scott would not have been

compelled to seek relief in the courts. Bradley v.

School Board of the City of Richmond, C.A. 4th

(1965), 345 F. (2d) 310.

The District Court’s award is clearly in accord with the

applicable law. As the Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit said in Clark et al. v. Board of Education of Little

Rock School District, 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir., 1966):

The grant or denial of attorney fees is a matter

wholly within the sound discretion of the trial court,

which may be reviewed only for abuses of that dis

cretion. . . . We do not exercise discretion in this field,

we only pass upon abuse.

However, the time has lapsed for experimental pol

icies proved ineffective. The Board is under an im

mediate and absolute constitutional duty to afford non-

racially operated school programs, and it has been

given judicial and executive guidelines for the per

formance of that duty. If well known constitutional

guarantees continue to be ignored or abridged and

individual pupils are forced to resort to the courts for

protection, the time is fast approaching when the ad

ditional sanction of substantial attorney fees should be

seriously considered by the trial courts. Almost solely

because of the obstinate, adamant, and open resistance

to the law, the educational system of Little Bock has

been embroiled in a decade of costly litigation, while

constitutionally guaranteed and protected rights were

collectively and individually violated. The time is com

ing to an end when recalcitrant state officials can force

unwilling victims of illegal discrimination to bear the

15

constant and crashing expense of enforcing their con

stitutionally accorded rights. 369 F.2d at 670-671.

This concurs with the views of Circuit Judges Sobeloff

and Bell expressed in their dissenting opinion in Bradley

v. School Board of the City of Richmond, supra:

We also dissent from the allowance of only $75.00

as counsel fees to the plaintiffs, which we deem egre-

giously inadequate. It will not stimulate school boards

to desegregate if they see that they can gain time by

resisting to the eleventh hour without effective dis

couragement of these tactics by the courts.

The principle applied by this court in Bell v. School

Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, 321 F.2d 494

(4th Cir. 1963), needs to be extended, not narrowed.

See Note 77 Harv. L. Rev. 1135 (1964). It ought not to

be reserved for the most extreme cases of official recal

citrance, but should operate whenever children are

compelled by deliberate official action or inaction to

resort to lawyers and courts to vindicate their clearly

established and indisputable right to a desegregated

education. Counsel fees are required in simple justice

to the plaintiffs. The award of fees in this equity suit

is in the court’s judicial discretion and should be com

mensurate with the professional effort necessarily ex

pended. One criterion which may fairly be considered

is the amounts found reasonable in compensating the

Board’s attorneys for their services. While public

monies, aggregating thousands of dollars, are paid de

fense lawyers, the attorneys for the plaintiffs who

have prosecuted these cases for two full rounds in the

District Court and on appeal are put off with a

miniscule fee of $75.00. 345 F.2d at 324-325.

16

See also Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of

Jackson, Tenn., 244 F. Supp. 353 (D.C.W.D., Tenn., 1965);

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 186 F.2d 473 (4th Cir.,

1951); 6 Moore’s Federal Practice (2nd Ed.) 1349, 1352. It

should be noted that the amount of attorneys’ fees awarded

($1000) is not particularly large, considering the amount of

effort which had to be expended in such a complex case.

R elief

For the foregoing reasons, Appellee contends that the

judgment of the District Court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Michael J . H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A von N. W illiams, J r.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Intervening

Plaintiff-Appellee

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. V. C. 219