Clay v. United States Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clay v. United States Brief for Petitioner, 1971. 3022a6b6-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c58298cb-8ae3-4030-b2e5-4d7e4a3fe6ee/clay-v-united-states-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

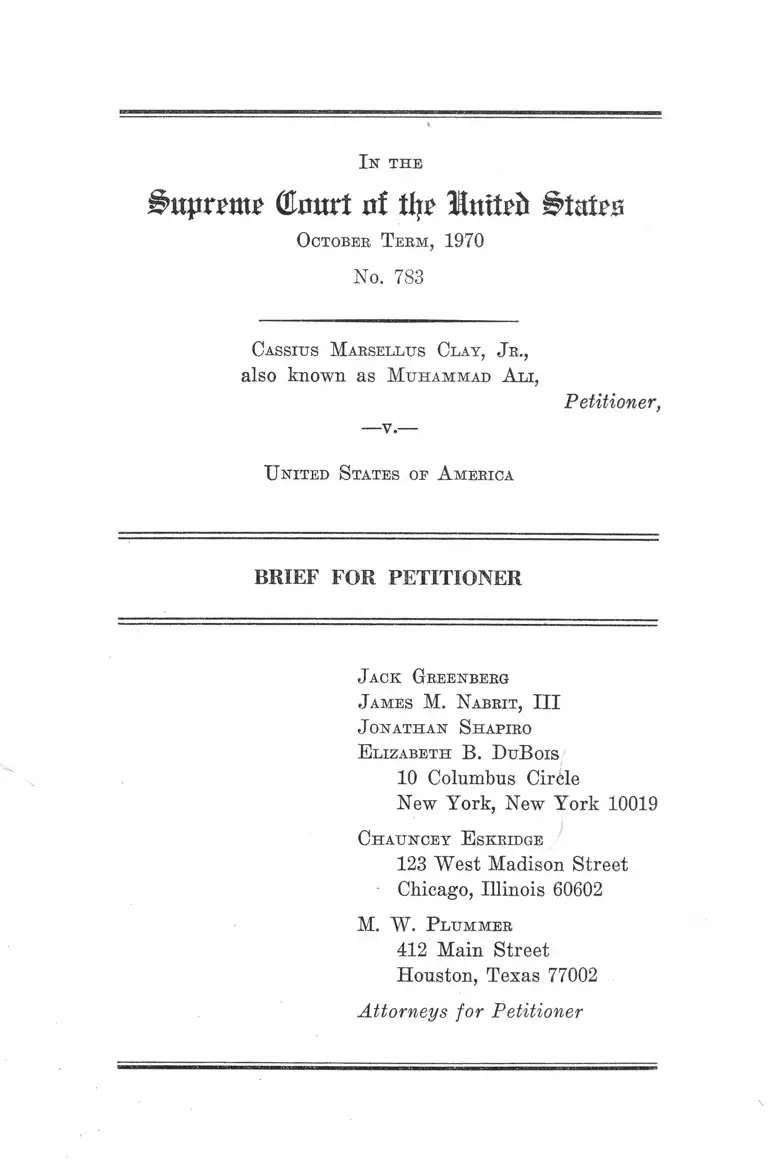

In THE

8>upvimw OInurt of % llmUh States

October Term, 1970

No. 783

Cassius Marsellus Clay, J r.,

also known as Muhammad A li,

— v.—

Petitioner,

U nited States of A merica

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

J onathan Shapiro

E lizabeth B. DuB ois

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Chauncey E skridge

123 West Madison Street

Chicago, Illinois 60602

M. W. Plummer

412 Main Street

Houston, Texas 77002

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Opinions B elow ..... .......... ............. ...... ................ ............... 1

Jurisdiction ... ................. ..... ........... ................... -............... 2

Constitutional Provision and Statute Involved ............. 2

Questions Presented for Review ....................................... 3

Statement of the C ase........................................................ 4

Summary of A rgument........... ............................................. 10

PAGE

A rgument

I. There Was No Basis In Fact For the Denial to

Petitioner of a Conscientious Objector Exemption 14

A. The Finding By The Department of Justice

That. Petitioner’s Beliefs Were Primarily Po

litical and Racial Was Erroneous and Consti

tuted a Violation of the First Amendment....... 14

B. The Department of Justice’s Conclusion That

Petitioner Was Not Opposed To Participation

in War in Any Form is in Conflict With This

Court’s Decision in Sicurella v. United States,

is Based Upon a Constitutionally Impermis

sible Interpretation of Religious Doctrine, and

Improperly Relies Upon Petitioner’s Objection

to the Vietnam War ........... ........... ....................... 22

1. Petitioner’s Objections to Participation in

War ................................................................... 23

2. The Teachings of the Nation of Islam ....... 28

3. The Vietnam War ......................... ............ . 36

IX

C. The Department of Justice Erred in Conclud

ing that Petitioner Had Failed to Sustain the

Burden of Establishing the Sincerity of His

Claim by Virtue of the Lateness of its Assser-

tion and the Fact that He Asserted Other Con

sistent Claims For Exemptions at the Same

Time ............................ ........................................... 39

II. Petitioner’s Conviction Must Be Reversed If The

Department of Justice’s Advice Was Erroneous

With Respect to Any One of the Grounds Upon

Which It Recommended That Petitioner Be De

nied a Conscientious Objector Exemption............. 46

Conclusion ............................... 50

Cases :

Abington v. School District of Schempp, 374 U.S. 203

(1963) ............................................................................... 19

Muhammad Ali v. State Athletic Commission, 316

F. Supp. 1246 (S.D. N.Y. 1970) .................................... 20

Banks v. Havener, 224 F. Supp. 27 (E.D. Va. 1964) ..... 16

Bates v. Commander, First Coast Guard District, 413

F.2d 475 (1st Cir. 1969) .............................................. 38

Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963) ......... ............... 7

Capobianco v. Laird, 424 F.2d 1304 (2d Cir. 1970) ....... 44

Carson v. United States, No. 398, O. T. 1969 ............... 18

Carson v. United States, 411 F.2d 631 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied, 396 U.S. 865 (1969) ................................. . 18

Cooper v. Pate, 382 F.2d 518 (7th Cir. 1967) ................. 15

Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968) .................... 19

Founding Church of Scientology v. United States, 409

F.2d 1146 (D.C. Cir. 1969)

PAGE

35

I ll

Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 IT.S. 67 (1953)...................19, 20

Fulwood v. Clemmer, 206 F. Supp. 370 (D. D.C.

1962) ......................................................................... ..... 16,20

Gillette v. United States, No. 85 O.T. 1970 ................... 37

Gonzales v. United Stales, 364 U.S. 59 (1960) ............... 7

Gordano v. United States, 394 U.S. 310 (1969) ............... 9

Kessler v. United States, 406 F.2d 151 (5th Cir. 1969) .. 38

Knuckles v. Prasse, 302, F. Supp. 1036 (E.D. Pa. 1969) 16

Kretchet v. United States, 284 F.2d 561 (9th Cir. 1960) 47

Long y . Parker, 390 F.2d 816 (3rd Cir. 1968)................. 16

Marsh v. Alabama, 362 U.S. 501 (1946) ........................ 20

Negre v. Larsen, No. 325, O.T. 1970 ............................. . 37

Niznik v. United States, 173 F.2d 328 (6th Cir. 1949) .... 20

Presbyterian Church v. Mary Elizabeth Blue Hull

Church, 393 U.S. 440 (1969)....... ........... ............... 12,30,35

SaMarion v. McGinnis, 253 F. Supp. 738 ( W.D. N.Y.

1966) ............................................... 16

Scott v. Commanding Officer, 431 F.2d 1132 (3rd Cir.

1970) ....................................... 48

Sewell v. Pegelow, 391 F.2d 196 (4th Cir. 1961)........... 16

Shepherd v. United States, 217 F.2d 942 (9th Cir.

1954) ....... 33

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963).......................... 19

Sieurella v. United States, 348 U.S. 385 (1955) .......3,12, 27,

28, 33, 46

Sostre v. McGinnis, 334 F.2d 906 (2nd Cir. 1964) ....... 15

Taffs v. United States, 208 F.2d 329 (8th Cir. 1953),

cert, denied, 347 U.S. 928 (1954) .............................. 33,44

United States v. Abbot, 425 F.2d 910 (8th Cir. 1970) .... 48

United States v. Ballard, 322 U.S. 78 (1944) ........... 21, 29, 35

PAGE

IV

United States ex rel. Barr v. Resor, 309 F. Supp. 917

(D. D.C. 1969) .................................. ............................... 16

United States v. Bornemann, 424 F.2d 1343 (2d Cir.

1970) .............................................. ...........................39,40,43

United States v. Bova, 300 F. Supp. 936 (E.D. Wis.

1969) ................................................................................. 49

United States v. Broyles, 423 F.2d 1299 (4th Cir.

1970) .......................................................... ....40,42,44,48

United States v. Corliss, 280 F.2d 808 (2d Cir. 1960),

cert, denied, 364 U.S. 884 (1960) .................................. 45

United States v. Cummins, 425 F.2d 646 (8th Cir.

1970) .............................................. 37,38,44

United States v. Freeman, 388 F.2d 246 (7th Cir. 1967) 16

United States v. Englander, 271 F. Supp. 182 (S.D.

N.Y. 1967) ....................................................................... 40, 48

United States v. Gearey, 368 F.2d 144 (2d Cir. 1966),

cert, denied, 389 U.S. 959 (1967) ................................... 40

United States v. Haughton, 413 F.2d 736 (9th Cir.

1969) ..........................................................................32,38,48

United States v. Hesse, 417 F.2d 141 (8th Cir. 1969) .... 45

United States v. Jakobson, 325 F.2d 409 (2d Cir. 1963)

aff’d sub nom. United States v. Seeger, 380 U.S. 163

(1965) ............................................................................... 48

United States v. Kauten, 133 F.2d 703 (2d Cir. 1943).... 17

United States v. Kuch, 288 F. Supp. 439 (D. D.C. 1969) 35

United States v. Lemmens, 430 F.2d 619 (7th Cir. 1970) 48

United States v. Macintosh, 283 U.S. 605 (1931).............. 14

United States v. Owen, 415 F.2d 383 (8th Cir. 1969) ....23, 32,

33,44, 45

United States v. Peebles, 220 F.2d 114 (7th Cir. 1955) 44

United States v. Pence, 410 F.2d 557 (8th Cir. 1969) .... 38

United States v. Prince, 310 F. Supp. 1161, 1165 (D.

Me. 1970) ....... 38

United States v. Purvis, 403 F.2d 555 (2d Cir. 1968)....7, 33

PAGE

V

United States ex rel Barr v. Resor, 309 F. Supp. 917

PAGE

(D. D.C. 1969) .................................................................. 15

United States v. Rutherford,------F .2d -------- (8th Cir.

No. 20,137, Feb. 3, 1971) .............................................. 43

United States v. Seeger, 380 U.S. 163 (1965) .....15,17,19,

23.29

United States v. Simmons, 213 F.2d 901 (7th Cir.

1954), rev’d on other grounds, 348 U.S. 453 (1955) .... 23

United States v. St. Clair, 293 F. Supp. 337, 344 (E.D.

N.Y. 1968) ................................................................. 23, 38, 48

United States v. Washington, 392 F.2d 37 (6th Cir.

1968) ............................. ................................................. . 48

Walker v. Blackwell, 411 F.2d 23 (5th Cir. 1969) ........... 15

Wallace v. Brewer, 315 F. Supp. 431 (M.D. Ala.

1970) ................................. ...................................... 16,20,21

Washington Ethical Society v. District of Columbia,

101 U.S. App. D.C. 371, 249 F.2d 127 (1957) ............... 19

Welsh v. United States, 398 U.S. 333 (1970)...... 10,15,16,

23.29

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U.S. 624 (1943).......................................................... 20

Witmer v. United States, 348 U.S. 375 (1955) ............... 45

Ypparila v. United States, 219 F.2d 465 (10th Cir. 1954) 48

Other A uthorities :

Maulana Muhammad Ali, Translation of the Holy

Qur’an 2 :190, 2 :191, 2 :216, 2 :217 and commentary at

pp. 80-81, notes 238, 239, pp. 90-91, note 277 (5th ed.

1963) ......................................... ........... ............................ 31

E. U. Essien-Udom, Black Nationalism, 308-323

(Paperback edition 1969) ................................... ........ 20, 36

VI

B. E. Garnett, “ Invaders from the Black Nation: The

Black Muslims in 1970” , Special Report, Race Rela

tions Information Center, Nashville, Tenn. (1970) ..15, 36

Hearings on Appropriations for the Judiciary and Re

lated Agencies, Department of Justice, Before the

Subeomm. on Departments of State, Justice and

Commerce, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. at 320 (1965); 2d

Sess. at 256 (1966); 90th Cong. 1st Sess. at 622

(1967); 2d Sess. at 543 (1968); 91st Cong. 1st Sess.

at 542 (1969) ............................ ................... ................... 21

C. E. Lincoln, The Black Muslims in America, 205,

219 (1961) ................................................................. 15,17, 36

E. Litt, Ethnic Politics in America, 89-91 (1970) ....... 36

Elijah Muhammad, Message to the Blackman in

America, 163,180 (1965) (Exhibit D to Special Plear

ing, A. 41a )..................................................................... 17, 30

PAGE

Statutes:

32 C.P.R. §1623.2 ................................................................. 43

32 C.P.R. §1625.1 ................................................................. 43

Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968

(18 U.S.C. §§2510 et seq.) .............................................. 21

United States Code

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ......................................................... 2

Universal Military Training and Service Act, Section

6 (j), 50 U.S.C. App. §456(j) .............2, 4,10,18, 22, 27, 29

I n the

§>uprm? ©oitrt of tlto lluitrii

October Term, 1970

No. 783

Cassius Marsellus Clay, J e.,

also known as Muhammad Ai/i,

—v.—

Petitioner,

U nited States op A merica

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit is reported at 430 F.2d 165 and is set out in the

Appendix (A. 236a). The opinion of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Texas is un

reported (R.P. Vol. I, 50-59).*

The opinion of the Court of Appeals at an earlier stage

of this case is reported at 397 F.2d 901 (A. 191a). Peti

tioner was originally convicted upon trial by jury in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

Texas, and no opinion exists with respect to that conviction.

The District Court denied petitioner’s motion for acquittal

* “R.P.” refers to the record of the proceedings in the District

Court pursuant to the order of this Court in No. 271, O.T. 1968

remanding the case for a determination of whether illegal electronic

surveillance of petitioner tainted his conviction. It consists of

three volumes of the printed Appendix from the Court of Appeals.

2

after an oral finding of a basis in fact for petitioner’s

selective service classification (A. 186a).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

July 6, 1970 and a timely petition for rehearing and re

hearing en banc was denied on August 19, 1970. Petitioner’s

time within which to file a petition for writ of certiorari

was extended until October 3, 1970 and the petition was

filed on October 1,1970. Certiorari was granted on January

11, 1971. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Constitutional Provision and Statute Involved

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution

provides in part:

“ Congress shall make no law respecting an establish

ment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise

thereof; . . . ”

Section 6 (j) of the Universal Military Training and

Service Act, 50 U.S.C. App. §456(j), provides:

“Nothing contained in this title . . . shall be construed

to require any person to be subject to combatant train

ing and service in the armed forces of the United

States who, by reason of religious training and belief,

is conscientiously opposed to participation in war in

any form. Eeligious training and belief in this con

nection means an individual’s belief in a relation to a

Supreme Being involving duties superior to those aris

ing from any human relation, but does not include

essentially political, sociological, or philosophical views

3

or a merely personal moral code. Any person claiming

exemption from combatant training and service be

cause of such conscientious objections . . . shall, if lie

is inducted into the armed forces . . . be assigned to

noncombatant service as defined by the President, or

shall, if he is found to be conscientiously opposed to

participation in such noncombatant service, in lieu of

induction, be ordered . . . to perform . . . civilian work

contributing to the maintenance of the national health,

safety, or interest . . .”

Questions Presented for Review

1. Whether petitioner’s conviction for refusal to submit

to induction into the Armed Forces should be reversed

because there was no basis in fact for the denial of his

claim for a conscientious objector exemption! This ques

tion subsumes the issues:

(a) Whether the finding by the Department of Justice

that petitioner’s beliefs were primarily “political

and racial” rather than “ religious” was erroneous

and violated petitioner’s religious freedom?

(b) Whether the Department of Justice’s conclusion

that petitioner was not opposed to “participation

in war in any form” is in conflict with this Court’s

decision in Sicurella v. United States, 348 U.S. 385

(1955), is based upon a constitutionally imper

missible interpretation of religious doctrine, and

improperly relies upon petitioner’s objection to

the Vietnam war?

(c) Whether the Department of Justice erred in con

cluding that petitioner had failed to sustain the

burden of establishing the sincerity of his claim

by virtue of the lateness of its assertion and the

4

fact that he asserted other consistent claims for

exemption at the same time?

2. Whether petitioner’s conviction must be reversed be

cause the Department of Justice’s advice was erroneous

with respect to at least one of the grounds upon which it

recommended that petitioner should he denied a conscien

tious objector exemption?

Statement of the Case

After a jury trial in the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Texas, petitioner was con

victed on June 20, 1967 of failing to submit to induction

into the armed forces in violation of 50 U.S.C. App. §462.

He was sentenced to five years imprisonment and a fine of

$10,000. He had been indicted on May 8, 1967 for his re

fusal on April 28, 1967 to take the traditional “ one step

forward” which symbolizes induction into the armed forces.

Petitioner originally registered with Local Board No. 47

in Louisville, Kentucky on April 18, 1960 and on March 9,

1962 the board classified him 1-A (A. 3a). As a result of

physical examinations which found him unacceptable for

induction on January 24, 1966 and again on March 13,

1964 (P. 538, 539),* petitioner was classified 1-Y on March

26, 1964 (A. 3a). But, because of an apparent lowering

of the Army’s standard for induction (P. 530), petitioner’s

file was reexamined and without a further physical ex

amination he was found fully acceptable for induction on

January 26, 1966 (F. 529). The local board mailed peti

* “F.” refers to the page number of petitioner’s Selective Ser

vice File, Government Exhibit No. 1 at the original trial (R. 139).

“R.” refers to the printed record of petitioner’s trial originally

filed in this Court in No. 271, O.T. 1968.

5

tioner notice of his acceptability on February 3, 1966

(A. 3 a ); he did not receive it, however, until February 12,

1966 (A. 11a).

In a letter dated February 14, 1966, petitioner sent to

his local board what he referred to as a “ request for pre

classification hearing” (A. 9a). He set forth certain in

formation which he considered relevant to an expected re

classification, including his recent divorce and property

settlement, the fact that he was the sole support of his

mother, and the pendency of a criminal charge against him

in Chicago. In addition, he stated:

“That I am a devoit [sic] Muslim and a follower of the

Islamic religious faith under the discipline of the

prophet Elijah Muhammad. To bear arms or kill is

against my religion and I conscientiously object to any

combat military service that involves the participation

in any war in which the lives of human beings is [sic]

taken. This I do not believe to be rightous [sic]. This

has been my faith upwards of 5 years” (A. 10a).

Three days later on February 17, 1966, however, the

local board reclassified petitioner 1-A (A. 4a). Only on

February 18,1966 did the board respond to the information

contained in petitioner’s letter of February 14th by send

ing him a Special Form for Conscientious Objector (SSS

Form No. 150 (A. 4a)). In the form, which he returned

to the board on February 28, 1966, petitioner claimed an

exemption on the basis of his conscientious opposition to

both combatant and noncombatant training and service in

the armed forces (A. 12a). He avowed his belief in a

Supreme Being and briefly described his religious beliefs

and duties a s :

“ Muslim—meaning peace—total submission to Will of

Allah. Do not take lives of anyone; nor war when not

6

ordered by Allah (God)—Keep up prayer and pay

poor rates (A. 13a).

* # *

“Islam teaches peace. Allah (God) forbids wars, except

when Islam is attacked. Holy Quran” (A. 15a).

He dated his conversion to Islam as January, 1964, by

confession of faith in Miami, Florida (A. 15a), and in

answer to the question concerning what behavior in his

life demonstrated the depth of his religious convictions,

he explained that:

“I divorced my wife whom I loved because she wouldn’t

conform to my Muslim faith. Gave up my Christian

name, and changed my name to Muhammad Ali, my

religious name. Declined movie roles not consistent

with my faith” (A. 14a).

He also stated that he believed in the use of force “ only

in sports and self-defense” (A. 14a).

The record of petitioner’s appearance before the local

board on March 17,1966 reports that he stated that Muslims

fight only in self defense, not war; that they have their

own police force, and that no Muslim may carry any lethal

weapon. The statement in this report that petitioner “ ob

jects to being in service because he has no quarrel with the

Yiet Cong,” is immediately followed by the statement that

“he could not, without being a hypocrit [sic], take part in

anything such as war or anything that is against the Moslim

[sic] religion” (A. 18a).

The board retained petitioner in class 1-A on March 17,

1966 and on March 28, 1966 he appealed its decision.

(A. 4a). In his letter of appeal he asserted that he was

entitled to a lower classification on medical grounds, for

hardship reasons, and because “my religious beliefs decree

7

that I not serve in any military purpose to promote war.

I reaffirm my stand thereon as my prior duty to Allah

(God) the Supreme Being over all.” (A. 21a).

On May 6,1966 the Kentucky appeal board reviewed peti

tioner’s file, tentatively determined that he should not be

classified in class 1-0 as a conscientious objector or in

any lower class, and referred the file to the Department

of Justice for an advisory recommendation and an FBI

investigation (A. 4a-5a, F. 472). After the completion of

the investigation, a special hearing was held on August

23, 1966 before former Kentucky Circuit Court Judge

Lawrence Grauman in Louisville, Kentucky, at which peti

tioner, his mother and father, his tax attorney, and an

assistant minister of Muhammad’s Mosque No. 29 of Miami,

Florida, testified (A. 22a-llla).

On the basis of this record, the hearing officer reported:

“that the registrant stated his views for about one hour

in a convincing manner; that he answered all questions

propounded to him forthrightly; that there was no

evidence of trying to evade . . . questions; and that he

was impressed by the registrant’s statements (A. 115a).

. . . [He] believed that . . . the registrant was of good

character, morals and integrity (A. 116a) . . . [and]

concluded that the registrant is sincere in his objec

tions on religious grounds to participation in war in

any form and he recommended that the conscientious

objector claim of the registrant be sustained” (A. 117a-

118a).1

1 This report was never disclosed to petitioner or even made

available to the appeal board even though it strongly supports his

claim for exemption. Cf. Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963) ;

Gonzales v. United States, 364 U.S. 59 (1960) ; United States V.

Purvis, 403 F.2d 555 (2d Cir. 1968).

8

Despite this completely favorable report, however, the

Department of Justice, in a letter to the appeal board from

T. Oscar Smith, Chief of the Conscientious Objector Section,

dated November 25, 1966, found that petitioner’s conscien

tious objector claim was not sustained and recommended

that he not be classified in class 1-0 or in class 1-A-O as a

conscientious objector to either noncombatant or combatant

service (A. 127a). The Department rejected the claim on

the ground that petitioner’s beliefs did not satisfy the statu

tory requirements that they be based on “religious training

and belief” and that they constitute objection “to participa

tion in war in any form.” It characterized petitioners’

beliefs, based on the teachings of the Nation of Islam, as

“political and racial” rather than religious; and concluded

that petitioner did not oppose participation in all wars, but

was only opposed to wars on behalf of the United States

(A. 121a), and to the Vietnam war in particular (A. 124a).

The Department also asserted that petitioner had failed to

sustain his burden of showing that his beliefs were sincere

because of his alleged failure to consistently manifest his

conscientious objector claim (A. 127a).

On the basis of this recommendation, but without setting

forth any reasons, the Kentucky appeal board classified

petitioner 1-A on January 6, 1967 (F. unnumbered). After

the return of his file from the appeal board, on January 12,

1967, the local board refused to reopen petitioner’s classifi

cation and reclassify him to IV-D as a minister of Islam

pursuant to his request of August 23, 1966 (A. 5a) At the

request of the National Selective Service Director Hershey,

however, on January 19, 1967 the board reopened peti

tioner’s classification but again classified him 1-A (A. Sa

ba). Petitioner appealed to the appeal board for the South

ern District of Texas (where he then resided) which, on

February 15, 1967, affirmed his 1-A classification (F. un

numbered).

9

General Hershey appealed petitioner’s classification to the

National Selective Service Appeal Board which voted to

classify petitioner 1-A on March 6, 1967 (A. 7a). Petitioner

was ordered to report for induction on April 28, 1967, at

which time he refused to submit.

At the subsequent trial, the District Court denied peti

tioner’s motion for acquittal on the ground that there was

a basis in fact for the denial of his claims for ministerial

and conscientious objector exemptions. With respect to

petitioner’s conscientious objector claim, the court merely

concluded:

“I don’t think he [petitioner] has said in so many words,

‘I am an [sic] conscientious objector, I do not believe

in killing or bearing arms and therefore I want to be

assigned to noncombatant duty or to work of national

importance under civilian direction” ’ (A. 190a).

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit quoted the passage from the

Department of Justice’s recommendation concerning the

“political and racial” nature of the teachings of the Nation

of Islam and the alleged objection only to certain wars; it

quoted at length from what it termed “ a penetrating anal

ysis of the beliefs of the Black Muslims” which emphasized

their allegedly anti-white, anti-Christian and segregationist

philosophy; and it pointed out that the Justice Department-

had found that petitioner had not established the sincerity

of his beliefs. Without further analysis, it found that “ there

was more than adequate evidence to justify the denial of his

claim” (A. 227a).

A petition for certorari was filed in this Court on July 7,

1968. As a result of the Solicitor General’s admission that

five conversations of petitioner had been monitored by elec

tronic surveillance, on March 24, 1969 this Court granted

the petition for certiorari, vacated the Court of Appeals’

10

judgment, and remanded the case to the District Court for

a determination of the effect of the surveillance on peti

tioner’s conviction. Giordano v. United States, 394 U.S.

310 (1969).

The District Court held that petitioner’s conviction had

not been tainted, and on July 24, 1969 it entered a new

judgment of conviction and resentenced him to five years’

imprisonment and a $10,000 fine (A. 2a). On his second ap

peal to the Fifth Circuit, petitioner raised again all of the

issues which had been decided against him on the first ap

peal, including the denial of the conscientious objector

exemption. The Court declined to reconsider its prior de

cision, with the exception, however, of determining that the

decision in Welsh v. United States, 398 U.S. 333 (1970) did

not affect its disposition of petitioner’s conscientious ob

jector claim (A. 249a).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

In order to support a claim for a conscientious objector

exemption under §6(j) of the Universal Military Training

and Service Act (hereafter referred to as the “Act” ), a

registrant is required to meet three basic tests. He must

demonstrate that he is conscientiously opposed to partici

pation in all wars; that this opposition is by reason of re

ligious training and belief; and that he is sincere in his

beliefs.

Petitioner was denied such an exemption in the present

case as a result of a decision by a Selective Service board2

2 After the Department’s adverse recommendation, petitioner

was classified 1-A by the appeal board for the Western District of

Kentucky on January 6, 1967 (P. unnumbered), by Local Board

No. 47 on January 19, 1967 (A. 5a-6a), by the appeal board for

11

which, did not give any reason for its rejection of his

claim. Bixt the advisory opinion from the Department of

Justice upon which this board relied, recommended that

petitioner’s claim be denied because of its failure to satisfy

any of the statutory criteria. All of the Department of

Justice’s conclusions, however, were clearly erroneous and

they cannot support the denial by the appeal board of

a conscientious objector exemption to petitioner. Since

there is no other basis in fact in the record for the denial

of the exemption, petitioner’s conviction should be reversed

and the indictment dismissed.

The Department of Justice rejected the findings of the

hearing officer that petitioner “is sincere in his objection

on religious grounds to participation in war in any form”

(A. 117a-118a). Indeed, it asserted that petitioner’s beliefs

did not satisfy the statutory requirements because they

“ rest on grounds which primarily are political and racial

. . . [and] constitute only objections to certain types of war

in certain circumstances . . .” (A. 122a-123a).

Petitioner submits that the Justice Department erred in

its conclusion with respect to both the source and the

content of his beliefs. Since the Nation of Islam clearly

constitutes a religion within the meaning of the Act, the

implicit determination that petitioner’s beliefs were not

“ religious” was erroneous. The refusal to recognize that

the Southern District of Texas on February 15, 1967 (F. unnum

bered), and by the National Appeal Board on March 6, 1967

(A. 7a). Presumably, each classification insofar as petitioner’s

conscientious objector claim was concerned was based upon a re

view of the same evidence. For the purpose of our consideration

here, it is immaterial that there was more than one denial of the

exemption after the Justice Department’s recommendation. If the

Department’s advice was erroneous, it is as likely to have infected

all of the decisions as it would only one decision. Consequently,

for convenience we will refer only to the denial of the exemption

by the Kentucky appeal board.

12

the Nation of Islam is a religion under the Act also

affronted the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious

freedom. Adherence by a registrant to unpopular “political

and racial” doctrines as part of his religious beliefs cannot

constitutionally provide the basis for discriminating

against him with respect to the statutory exemption.

The conclusion that the contents of petitioner’s views on

war did not qualify him for the exemption was equally de

fective. Since the only war which the record reflects that

petitioner was willing to participate in was a theocratic or

holy war, the Department’s conclusion that he was not

opposed to participation in all war is in conflict with this

Court’s decision in Sicurella v. United States, 348 U.S. 385

(1955). Since it is the registrant’s views on war that are

central to his entitlement to the exemption, it was error

for the Department of Justice to consider the doctrines of

petitioner’s religion in the face of his own unequivocal ob

jection to participation in all wars. However, the doc

trines of the Nation of Islam are perfectly consistent with

petitioner’s beliefs in that they prohibit participation in

all war except theocratic war. The Department’s contrary

conclusion was based on an interpretation of the meaning

and significance of religious doctrines that is forbidden by

the First Amendment and is in conflict with this Court’s

decision in Presbyterian Church v. Mary Elisabeth Blue

Hull Church, 393 U.S. 440 (1969). And to the extent that

the Department relied on petitioner’s expression of opposi

tion to the Vietnam war to support its conclusion that

petitioner merely objected to participation in a particular

war, it also erred. Opposition to the war in Vietnam is

consistent, rather than inconsistent, with conscientious ob

jection to all armed conflict.

Finally, in its recommendation to the appeal board the

Justice Department erroneously implied that petitioner

13

could not, as a matter of law, meet his burden of establish

ing his sincerity because of the lateness of the filing of his

claim. It was also error for the Department to maintain

that the appeal board could even consider lateness as evi

dence from which it could draw an inference of insincerity.

Petitioner was not required to bring his claim to the atten-

of his local board any sooner than he did because he was

unacceptable for induction for virtually the entire period

from when his conscientious objections to war crystallized

until when he did assert the claim. Petitioner’s persuasive

and fully corroborated explanation of why he did not file

his claim until February, 1966, moreover, completely rebuts

any inference of insincerity. And the fact that petitioner

simultaneously sought several exemptions for different,

but not inconsistent, reasons is totally irrelevant to the

sincerity with which he asserted his conscientious objector

claim.

II

Since no reason was provided by the appeal board for

the denial of a conscientious objector exemption to peti

tioner, it is impossible to determine whether it concluded

that petitioner’s beliefs did not satisfy the statutory re

quirements because they were not “religious,” because they

did not constitute objections to all wars, or because they

were not sincerely held. Inasmuch as petitioner clearly

made out a prima facie case of his entitlement to the ex

emption, if any of the Department of Justice’s advice upon

which the appeal board may have relied was erroneous, his

conviction must be reversed. The integrity of the Selective

Service System can only be maintained if courts do not

blindly endorse draft board decisions that are based upon

errors of law. And serious criminal convictions cannot be

supported by determinations so fraught with doubt.

14

ARGUMENT

I.

There Was No Basis In Fact For the Denial to Peti

tioner of a Conscientious Objector Exemption.

A. The Finding By The Department of Justice That

Petitioner’s Beliefs Were Primarily Political and

Racial Was Erroneous and Constituted a Viola

tion of the First Amendment.

That petitioner’s opposition to war was the result of

“ religions training and belief” within the meaning of §6(j)

of the Act cannot be doubted. It was never open to question

that petitioner’s beliefs were based on the doctrines of

the Lost Found Nation of Islam, and it is clear that the

Nation of Islam is a religion within the traditionally ac

cepted meaning of that term. In the language of Chief Jus-

tice Hughes in United States v. Macintosh, 283 U.S. 605

(1931):

“ The essence of religion is belief in a relation to God

involving duties superior to those arising from any

human relation” (283 U.S. at 633-34) (dissenting

opinion).

And, in Welsh v. United States, 398 U.S. 333 (1970), after

a careful analysis of the legislative history, Justice Harlan

concluded that religion within the meaning of §6(,j) meant

at least the “ formal organized worship or shared beliefs by

a recognizable and cohesive group” (398 U.S. at 353) (con

curring opinion).

It is unnecessary to belabor the point that the Nation of

Islam falls within either of these conventional definitions,

both of which are far narrower than the definitions or reli

15

gion endorsed by this Court in both Welsh and United

States v. Seeger, 380 U.S. 163 (1965). It is based on a belief

in Allab as the Supreme Being, and the Koran or Holy

Qur’an is the chief source of its dogma. The religious

doctrines and rituals of the members of the Nation, also

known as Muslims or Black Muslims, are derived largely

from classical Islam, but their beliefs on certain funda

mental points have clearly been shaped by the experience

of the Black man in the United States.3 Despite certain

wide departures from the traditions of orthodox Islam,

however, Elijah Muhammad, the Nation’s spiritual leader,

was welcomed to Mecca in 1960 by the powerful Hajj Com

mittee, which is responsible for accepting or rejecting

pilgrims journeying to the Holy City.4

Consistent with this country’s tradition of religious toler

ance, courts have not hesitated to recognize the Nation of

Islam as a valid religion that is entitled to the same con

stitutional protection accorded to other religious move

ments.5 As one federal court concluded:

“It is sufficient here to say that one concept of religion

calls for a belief in the existence of a supreme being

3 C. E. Lincoln, The Black Muslims in America 219 (1961) [here

after cited as Lincoln]. The Nation’s formal organization can be

traced to the early 1930s in Chicago, but its spiritual roots probably

lie in the Moorish Science Temple Movement of Noble Drew Ali

and the United Negro Improvement Association of Marcus Garvey,

both of which flourished after World War I. Id. at 50. Ever

since the early years of the movement Elijah Muhammad, known

as the “Prophet” and the “Messenger of Allah,” has been its

spiritual leader. Under his guidance, the membership of the Na

tion of Islam has increased to what was conservatively estimated

at 100,000 in 1961, with more than fifty temples in major cities

from coast to coast. Id. at 217.

4 B. E. Garnett, “ Invaders from the Black Nation: The Black

Muslims in 1970,” p. 12, Special Report, Race Relations Informa

tion Center, Nashville, Tenn. (1970).

5 See Cooper v. Pate, 382 F.2d 518 (7th Cir. 1967); Walker v.

Blackwell, 411 F.2d 23 (5th Cir. 1969); Sostre v. McGinnis, 334

16

controlling the destiny of man. That concept of reli

gion is met by the Muslims in that they believe in

Allah, as a supreme being and as the one true god. It

follows, therefore, that the Muslim faith is a religion”

(Fulwood v. Clemmer, supra, 206 F. Supp. at 373).

Yet, faced with the overwhelming evidence that the Na

tion of Islam is a religion as well as with the conclusion

of the hearing officer that petitioner’s opposition to war

■was a result of “ religious training and belief,” the Depart

ment of Justice concluded that petitioner’s opposition to

war “ insofar as it is based on the teachings of the Nation

of Islam rests on grounds which primarily are political

and racial” (A. 122a). In light of the fact that §6(j) ex

pressly denies an exemption to registrants whose views

on war are “ essentially political, sociological or philosoph

ical,” there can be no doubt the appeal board would con

clude that it was the Justice Department’s opinion that

petitioner should be denied an exemption because Ms views

were “primarily political and racial.” 6

Read as a whole, the Justice Department opinion letter

and the resume of the FBI investigation reinforce the con

clusion that the Department wTas of the view that petitioner’s

F.2d 906 (2nd Cir. 1964) ; Sewell v. Pegelow, 391 F.2d 196 (4th

Cir. 1961) ; Long v. Parker, 390 F.2d 816 (3rd Cir. 1968); Wallace

v. Brewer, 315 F. Supp. 431 (M.D. Ala. 1970) ; Knuckles v. Prasse,

302 F. Supp. 1036 (E.D. Pa. 1969); SaMarion v. McGinnis, 253

F. Supp. 738 (W.D. N.Y. 1966); Banks v. Havener, 224 F. Supp.

27 (E.D. Va. 1964); Fulwood v. Clemmer, 206 F. Supp. 370 (D.

D.C. 1962) cf. United States v. Freeman, 388 F.2d 246 (7th Cir.

1967); United States ex rel. Barr v. Besor, 309 F. Supp. 917 (D.

D.C. 1969).

6 This was especially true before this Court made it clear in

Welsh v. United States, 398 U.S. 333 (1970) that opposition to war

that is based on political views or other beliefs that are nonreligious

in the conventional sense does not automatically defeat a reg

istrant’s claim for exemption.

17

claim should be denied because it was not “ religious.”

First, United States v. Kauten, 133 F.2d 703 (2d Cir. 1943)

is the only case cited by the Department in support of its

determination that petitioner’s beliefs did not satisfy the

statutory requirements (A. 123a). As this Court recog

nized in United States v. Seeger, 380 U.S. 163 (1965),

Kauten was a case which held “that exemption must

be denied to those whose beliefs are political, sociological

or philosophical in nature, rather than religious” (380 U.S.

at 178). Secondly, the Department did not refer to the

Nation of Islam as a religion anywhere in the opinion let

ter. Not only did it studiously ignore any acknowledgement

of the conventional religious aspects of the Nation, but it

emphasized what it obviously considered its nonreligious

characteristics. Thus, it characterized the teachings of the

Nation of Islam as “political and racial objections to pol

icies of the United States as interpreted by Elijah Muham

mad” (A. 121a), and it pointed out that the essential views

of the Black Muslims are “that the white man is their

enemy, and that the black man should disassociate him

self from the United States Government and its institutions

and secure an independent nation for the black man within

the United States” (A. 120a-121a). Finally, the discussion

of the doctrines of the Nation of Islam contained in the FBI

resume mentioned only its allegedly anti-white attitude,

the fact that some of its members have refused to register

under the Selective Service Act, the existence of a “mil

itary-like” organization known as the Fruit of Islam, and

the erroneous report that Muslims disclaim allegiance to

the United States (A. 151a-152a).7

7 Muslims are directed to respect and obey the laws of the United

States (A. 37a). See also Elijah Muhammad, Message to the Black

man in America, 163, 180 (1965) (Exhibit D to Special Hearing,

A. 41a). It has been observed that Muslims are scrupulous in this

obedience. Lincoln, at 248.

18

Indeed, on at least one occasion the Justice Department

at its highest level has explicitly taken the position that

the Nation of Islam is not a religion within the meaning

of §6(j) of the Act. Thus, in his memorandum in opposi

tion to the grant of certiorari in Carson v. United States,

No. 398, O.T. 1969, the Solicitor General argued that a

local hoard could properly deny a conscientious objector

claim that was based on the teachings of the Nation of Islam

because the registrant’s “ alleged opposition to war was not

based on ethical principles but on essentially political

views” (Memorandum for the United States in Opposition,

p. 2). And in affirming that registrant’s conviction the

Fifth Circuit evidently accepted the Department’s argu

ment for it concluded that his beliefs “ reflect an opposition

to war which smacks of being essentially political, rather

than religious . . . ” Carson v. United States, 411 F.2d 631,

633 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 396 U. S. 865 (1969).8

The effect of the Department of Justice’s letter, there

fore, was to recommend that petitioner be denied a con

scientious objector exemption on the ground that his oppo

sition to participation in war was not “religious.” Such a

recommendation was clearly erroneous and cannot support

the denial of petitioner’s claim because, as we have pointed

out, the Nation of Islam satisfies the accepted definition

of religion within the meaning of the Act.

By refusing to recognize the Nation of Islam as a religion

because of its allegedly “political and racial” teachings,

8 During petitioner’s trial the United States Attorney even re

marked that petitioner:

“became converted to the Muslim faith in 1964. In my opinion

that is where his troubles began. This tragedy and the sadness

of having lost his title and having been convicted of a serious

felony I think is because of his coming under the influence of

the Muslim faith in the United States, which is just as much

political as it is religious” (R. 355).

19

moreover, the Justice Department penalized petitioner be

cause of what he believed, and it deprived him of the bene

fits of the statutory exemption afforded to the members of

all other faiths. In so doing, the Department violated the

governmental neutrality toward religion that is commanded

by the First Amendment.

As this Court recently stated in Epperson v. Arkansas,

393 IT. 8. 97 (1968):

“ Government in our democracy, state and national, must

be neutral in matters of religious theory, doctrine and

practice. It may not be hostile to any religion or to

the advocacy of nonreligion; and it may not aid, foster,

or promote one religion or religious theory against

another or even against the militant opposite. The

First Amendment mandates governmental neutrality

between religion and religion and religion, and between

religion and nonreligion” (393 TJ. S. at 103-04).

Thus, the constitutional ideal is “absolute equality before

the law, of all religions, opinions and sects,” Abington v.

School District of Schempp, 374 IT. S. 203, 215 (1963),

and the Government may not “penalize or discriminate

against individuals or groups because they hold religious

views abhorrent to the authorities,” Sherbert v. Verner, 374

TJ. S. 398 (1963); Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U. S. 67

(1953). Local boards and courts, therefore, may no more

reject the religious beliefs of a registrant because they

consider them “political and racial” than they can because

they consider them “ incomprehensible.” United States v.

Seeger, 380 IT. S. 163, 194-95 (1965); see Washington

Ethical Society v. District of Columbia, 101 IT.S. App. D.C.

371, 249 F.2d 127 (1957).

A central purpose of the First Amendment was to pro

tect the adherents of unorthodox and unpopular faiths such

20

as petitioner’s from persecution and discrimination at the

hands of the majority. But on the record in this case, it

cannot be said that just such persecution did not account

for the Department’s adverse recommendation and the sub

sequent denial of petitioner’s conscientious objector claim.

The Black Muslims have been commonly, although errone

ously, thought to be a fanatical, extremist, black nationalist

organization intent upon achieving political separation

through violence. See E. U. Essien-Udom, Black Nation

alism 308-323 (Paperback edition 1969). The fear, hatred

and distrust that it has engendered among white people

has often resulted in political and religious oppression,

see e.g., Wallace v. Brewer, 315 P. Supp. 431 (M.D.

Ala. 1970); Fultvood v. Clemmer, 206 F. Supp. 370 (D.D.C.

1962); Muhammad Ali v. State Athletic Commission, 316

F. Supp. 1246 (S.D. N.Y. 1970), that recalls that to which

the Jehovah’s Witnesses were subjected not long ago. See

e.g., Marsh v. Alabama, 362 U. S. 501 (1946); Fowler v.

Rhode Island, supra; West Virginia State Board of Edu

cation v. Barnette, 319 IT. S. 624 (1943) ; Nisnik v. United

States, 173 F.2d 328 (6th Oir. 1949). Indeed, the record in

this case is replete with evidence of the hostility and re

sentment that was directed at petitioner both because of

his race and his religious affiliation.9

The official hostility toward the Muslims has been shared

by the federal government, which has itself been deeply

involved in the investigation of the Nation of Islam for

9 The FBI resume, for example, is full of examples of how peo

ple thought that the Muslims were hatemongers (A. 130a) who had

brainwashed petitioner (A. 134a) and that petitioner was stupid to

associate with them (A. 135a). In addition, petitioner’s Selective

Service file contains hundreds of letters and newspaper articles

reflecting racial and religious prejudice against him (A. 233a).

These documents had been sent to the local board and placed in

petitioner’s file pursuant to regulation (R. 175).

21

many years.10 This investigation has included systematic

FBI wiretapping and electronic surveillance of the Mus

lims, and around the clock wiretaps on the phones of

the Muslim spiritual leader, Elijah Muhammad.11 Indeed,

Mr. Hoover has called the Muslims “a very real threat to

the internal security of the Nation,” 12 and the use of wire

tapping indicates that his conclusion was taken seriously

by the Attorney General.13 Gf. Wallace v. Brewer, supra,

315 F. Supp. at 441, 440-50.

In such a context, it is little wonder that the Justice De

partment, which was at the same time treating the Muslims

as political terrorists, would conclude that the Nation of

Islam was not a religion, or that the appeal board would

rely upon that conclusion to deny petitioner a conscientious

objector exemption. In United States v. Ballard, 322 U. S.

78, 87 (1944), Justice Douglas remarked:

“If one could be sent to jail because a jury in a hostile

environment found those [religious] teachings to be

false, little indeed would be left of religious freedom”

10 See Testimony of J. Edgar Hoover at the Hearings on Appro

priations for the Judiciary and Belated Agencies, Department of

Justice, Before the Subcom. on Departments of State, Justice and

Commerce, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. at 320 (1965); Id. 2d Sess. at 256

(1966) ; Id. 90th Cong. 1st Sess. at 622 (1967); Id. 2d Sess. at 543

(1968) ; Id. 91st Cong. 1st Sess. at 542 (1969).

11 Three out of the four logs of illegal surveillances that were dis

closed to petitioner in the course of the remand proceedings in this

ease resulted from wiretaps on the phones of Elijah Muhammad

in Phoenix, Arizona and Chicago, Illinois (A. 238a- 239a).

12 See Hearings, supra note 10, 90th Cong. 1st Sess. at 622

(1967) .

13 Prior to the enactment of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe

Streets Act of 1968 (18 U.S.C. §2510 et seq.) wiretapping could

only be undertaken by federal officers with the express authorization

of the Attorney General in cases where national security was at

stake (See Memoranda of Presidents Roosevelt, Truman and John

son (R.P. Yol. I 16-21)).

22

But that is just what happened to petitioner when the

Department of Justice denied the validity of his religious

beliefs, the Selective Service System rejected his consci

entious objector claim, and the courts below found him

guilty.

The First Amendment means at the very least that Gov

ernment cannot, because of a dislike of religious doctrines,

deny to the followers of one religion what it accords to

adherents of others. However abhorrent are the beliefs of

the Black Muslims to the Department of Justice—however

“political and racial” it considers the sources of their

doctrines—the Nation of Islam nevertheless constitutes a

religion within the contemplation of the Act and its mem

bers are entitled to the benefits of the conscientious ob

jector exemption. There was no basis in fact, therefore,

for denial of petitioner’s claim on the ground that his

opposition to participation in war was not based on “re

ligious training and belief.”

B. The Department of Justice’s Conclusion That

Petitioner Was Not Opposed To Participation in

War in Any Form is in Conflict With This Court’s

Decision in Sicurella v. United States, is Based

Upon a Constitutionally Impermissible Interpre

tation of Religious Doctrine, and Improperly

Relies Upon Petitioner’s Objection to the Vietnam

War.

With respect to the substance of petitioner’s objections

to war, the Justice Department concluded that he did not

satisfy the requirements of §6(j) because he was only op

posed to participation in certain types of war in certain cir

cumstances rather than to war in any form (A. 122a-123a).

This determination was based entirely upon three consid

erations: the fact that, in the Department’s view, peti

tioner had admitted that there were some wars in which

23

lie would participate; the Department’s view that the teach

ings of the Nation of Islam only precluded participation

in war on behalf of the United States; and the fact that

petitioner had expressed the opinion that he could not

participate in the Vietnam war. As we point out below,

none of these considerations can support the conclusion that

petitioner was not opposed “to participation in war in any

form.” On the contrary, the record convincingly estab

lishes that petitioner’s convictions with respect to war satis

fied the statutory test.

1. Petitioner’s Objections to Participation in War.

"VVe start with the premise that it is the convictions, of the

registrant and not the doctrines of his religion that must be

the central concern of the Selective Service System. United

States v. Seeger, 380 U. S. 163, 184-185 (1965). Thus,

affiliation with a particular religious sect, even though it

may be pacifist, does not automatically entitle one to

conscientious objector status, United States v. Simmons,

213 F.2d 901 (7th Cir. 1954), rev’d on other grounds, 348

U. S. 453 (1955), nor does the fact that a registrant’s

religion does not proscribe participation in war disqualify

him for the exemption. United States v. St. Clair, 293

F. Supp. 33 (E.D. N.Y. 1968). It is, of course, unnecessary

that the conscientious objection arise from church member

ship at all. United States v. Owen, 415 F.2d 383 (8th Cir.

1969). As this Court has recently held, it is enough that

because of beliefs which “ function as a religion in his life,”

a registrant is opposed to participation in all wars. Welsh

v. United States, 398 U. 8. 333, 339 (1970).

The record in this case clearly establishes that petitioner

was opposed, because of his interpretation of the doctrines

of his religion, to participation in all war with the excep

24

tion of a theocratic war or a war in which he was directed

to fight by Allah.

At the special hearing before Judge Grauman, petitioner

discussed his opposition to war in considerable detail. He

stated that:

“ the Holy Qur’an do teach us that we do not take part

of—in any part of war unless declared by Allah him

self, or unless it’s an Islamic World War, or a Holy

War, and . . . we are not to even as much as aid

the infidels or the nonbelievers in Islam, even to as

much as handing them a cup of water during battle”

(A. 68a).

Later he explained his understanding of what he had de

scribed as the “Islamic World War,” the “Holy War” or

the “War of Armageddon:”

“We are only preparing for the war of Armageddon

divinely. We talk that the battle will be between good

and right, truth and falsehood, and we are taught that

the battle will be between God and the Devil and so

therefore, we hope and pray that we are still with the

Honorable Elijah Muhammad, for when that hour and

day come that we can be told what side to go to. We

are trying to be prepared where we can go on the

right side. . . . and we just hope that we are spiritually

and physically and internally and mentally and morally

able to get on the side of Allah and the Honorable

Elijah Muhammad when Armegeddon start . . . for we

are only preparing for Allah in spirit . . . in a spiritual

way” (A. 106a).

Even in the holy war, which petitioner believed would be a

physical conflict between the forces of good and evil

(A. 107a), he did not believe that he or his fellow Muslims

would actually participate.

25

Indeed, in the course of the hearing petitioner stated that

he would not fight in a war unless:

“the Honorable Elijah Muhammad looked me in the

face and he who I believe is directly from Allah, Al

mighty God Allah, and if he looked at me and advised

me, which I ’m sure he wouldn’t do, to fight in any

kind of war, if he advised me to I would” (A. 101a).

When further pressed on the hypothetical question as to

whether he would fight if Elijah Muhammad told Mm to,

petitioner made it clear that he thought any such command

was inconceivable. He said:

“I can speak for him [Elijah Muhammad] right here

and now, that I know he would not say anything like

that if he is truly following the Holy Qur’an and what

he teaches us that God taught him . . . I don’t believe

that, and I would actually say that I could guarantee

you my life that he won’t advise me to do something

like that . . . ” (A. 101a-102a).

Otherwise, petitioner believed in the use of force only

for self-defense. He explained:

“ [B ]y our teaching and by wre believing in God, whose

law is self-preservation, we are taught not to be the

aggressor, but defend ourselves if attacked and a man

cannot defend himself if he knows not how. . . . So,

we, the Muslims to keep in physical condition, we do

learn how to defend ourselves if we are attacked since

we are attacked daily through the streets of America

and have been attacked without justification for the

past four hundred years” (A. 104a-105a).

Finally, petitioner considered boxing a sport and himself

a scientific boxer who was not “violent” in the ring:

“I never get violent. I never lose my head and I ’m

known for being a calm, cool boxer and I never feel as

26

though I ’m violent and I never fight and act like I ’m

violent” (A. 98a).

Petitioner’s testimony at the special hearing was per

fectly consistent with every statement he had previously

made in connection with his conscientious objector claim

from the time he first asserted it on February 14, 1966. In

his letters of February 14th and March 28th, in his special

conscientious objector form (SSS Form No. 150), and at

his personal appearance before the local board he main

tained that he was opposed to taking any part in earthly

wars and to killing human beings (A. 10a, 13a, 18a, 21a).

Literally everyone who testified on behalf of petitioner at

the special hearing or who was interviewed by the FBI,

moreover, was of the opinion that petitioner was opposed

to participation in any military service whatsoever (E.g.

A. 27a, 32a, 54a, 56a, 133a, 134a, 135a, 136a, 137a, 139a).

In the face of his consistent and unequivocal opposition to

participation in all wars, the Department of Justice could

find only one remark made by petitioner in the entire record

to support its conclusion that there are real wars in which

petitioner would participate. At one point, petitioner ex

plained that the Holy Qur’an and Elijah Muhammad taught

Muslims:

“that we are not to participate in wars on the side of

nobody who—on the side of nonbelievers, and this is a

Christian country. . . . So we are not, according to the

Holy Qur’an, even as much as aid in passing a cup of

water to the—even a wounded” (A. 96a-97a).

Presumably, on the basis of the negative implication of

the statement that Muslims were taught not to participate

in wars on the side of nonbelievers, the Department con

cluded that petitioner was willing to fight in wars on behalf

27

of Muslims. But even assuming that this is a fair reading

of petitioner’s statement, it is perfectly clear in light of

the rest of his testimony that the only war he would ever

participate in, even on the side of Muslims, was a Holy

War or a war in which he was directed to fight by Allah.

Indeed, this fragmentary statement upon which the Depart

ment places so much reliance is perfectly consistent with

petitioner’s previous statement that “ the Holy Qur’an do

teach us that we do not take p art. . . of war unless declared

by Allah himself, or unless its an Islamic World War, or

a Holy War, and . . . we are not to even as much as aid the

infidels or the nonbelievers in Islam, even to as much as

handing them a cup of water during battle” (A. 68a). Thus,

at the only time that Muslims could ever participate in

war, the war of Armageddon, petitioner would take part

on the side of Islam; but at all other times he would not

give the slightest amount of aid to anybody engaged in war.

In Sicurella v. United States, 348 U. S. 385 (1955), this

Court held that this kind of theocratic conflict was not

“war” within the meaning of § 6(j) and that a registrant’s

willingness to participate in it did not disqualify him for a

conscientious objector exemption. In words equally appro

priate to this case, the Court said:

“ Granting that these articles picture Jehovah’s wit

nesses as anti-pacifists, extolling the ancient wars of

the Isrealites and ready to engage in a ‘theocratic war’

if Jehovah so commands them, and granting that the

Jehovah’s Witnesses will fight at Armageddon, we do

not feel this is enough. The test is not whether the

registrant is opposed to all war, but whether the regis

trant is opposed on religious grounds, to participation

in war. As to theocratic war, petitioner’s willingness

to fight on the orders of Jehovah is tempered by the

fact that, so far as we know, their history records no

28

such command since Biblical times and their theology

does not seem to contemplate one in the future. And

although the Jehovah’s Witnesses may fight in the

Armageddon, * * * [we] believe that Congress had in

mind real shooting wars. . . . We believe the reasoning

of the Government . . . is so far removed from any

possible congressional intent that it is erroneous as a

matter of law” (348 U.S. at 390-91).

Petitioner’s views on war, based upon his understanding

of the doctrines of the Nation of Islam, are indistinguish

able in any material respect from those of the Jehovah’s

Witness in Sicurella. He was opposed to all except theo

cratic war, he would fight only in self-defense, he did not

believe in carrying weapons and there was no possibility

in his mind that he would ever be commanded to engage

in war by his God. Consequently, there was nothing in

petitioner’s beliefs that could provide a basis in fact for

the denial of his claim. To the extent that the Justice

Department relied on them, its recommendation is errone

ous as a matter of law.

2. The Teachings of the Nation of Islam.

In its advice letter the Department took the position that

the doctrines of the Nation of Islam precluded only partici

pation in war on behalf of the United States, but allowed

participation in earthly wars on behalf of other, presum

ably Muslim, nations. But as we have pointed out above,14

it is only petitioner’s views on war, not those of his

religion, that are relevant to his conscientious objector

claim. Thus, even if the Department’s interpretation

of the Muslim doctrines concerning participation in war

14 See p. 23, supra.

29

was a reasonable one it could not legitimately provide

a basis for rejecting petitioner’s claim in the face of his

interpretation that those doctrines precluded him from par

ticipating in any earthly war. See United States v. Seeger,

380 U. S. 165, 184 (1965); Welsh v. United States, 398 U. S.

333 (1970). Even if on the basis of some theological

absolute petitioner misinterpreted the doctrines of the Na

tion of Islam, he is nevertheless entitled to the exemption

because, as the hearing officer found and the record over

whelmingly supports, he was opposed to participation in

all earthly wars by reason of what he believed to be the

dictates of his religion.

But even assuming that the doctrines of the Nation of

Islam are considered relevant in the abstract to petitioner’s

conscientious objector claim, the record in this case demon

strates that these doctrines support and are completely

consistent with the beliefs petitioner expressed. The con

trary conclusion by the Department of Justice not only finds

no support in the record, but is based on the kind of inter

pretation and analysis of the meaning and significance of

Muslim religious doctrines that is forbidden by the First

Amendment.

In determining whether the doctrines of a particular

religion preclude participation in all war within the mean

ing of § 6 ( j) of the Act, the Government must be limited

to a literal reading of the tenets of the faith. It must take

at face value what is stated in the accepted sources of the

religion or by the accepted religious spokesmen; it may

not supply its own interpretation of the religion or any

of its doctrines. See United States v. Ballard, 322 U. S. 78

(1944). For as this Court has held, the First Amendment

forbids courts or other secular authorities from playing

any role in determining the “ interpretation of particular

church doctrines and the importance of those doctrines to

30

the religion.” Presbyterian Church v. Mary Elizabeth Blue

Hull Church, 393 U. S. 440 (1965). This is so because:

“If civil courts undertake to resolve such controversies

[over religious doctrine] . . . the hazards are ever

present of inhibiting the free development of religious

doctrine and of implicating secular interests in mat

ters of purely ecclesiastical concern” (393 U. 8. at 449).

The Justice Department and the Selective Service System,

therefore, can no more make petitioner’s entitlement to a

conscientious objector exemption turn upon their interpre

tation of certain doctrines of the Nation of Islam, than

could the Georgia courts award church property on the

basis of the interpretation and significance that they as

signed to aspects of church doctrine.

The “neutral principle” which must govern the Govern

ment’s determination of whether or not the doctrines of a

particular religion preclude participation in all war, to the

extent such an inquiry is relevant, is that Government in

quiry must stop at a literal reading of accepted religious

sources. In short, it may not interpret or analyze the doc

trines of the religion.

Such a reading of the sources in this record is com

pletely in accord with petitioner’s own understanding of

the meaning of Muslim doctrines concerning participation

in war. Elijah Muhammad explained the meaning of Islam

in his Message to the Blackman in America (1965) (Ex. D

to Special Hearing, A. 41a) in this way:

“ The author of Islam is Allah (God). We just cannot

imagine God being the author of any other religion

hut one of peace. Since peace is the very nature of

Allah (God), and peace He seeks for his people and

peace is the nature of the righteous, most surely Islam

is the religion of peace (p. 68).

* # *

31

“The very dominant idea in Islam is the making of peace

and not war; onr refusing to go armed is our proof

that we want peace” (p. 322).

Muslims are, therefore, forbidden to carry weapons or to

participate in any war and one of the central dogmas of

their faith states:

“We believe that we who declared ourselves to be righ

teous Muslims should not participate in wars which

take the lives of humans” (Id. at 164).

The only use of force that is consistent with the Muslim

faith is self-defense, which Elijah Muhammad believes is

justified by God and by Divine Law (Id. at 217). But even

then, Muslims may not use weapons; if they are attacked

by armed persons they must rely upon Allah to protect

them (Id. at 319).15 16

Although Muslim doctrine condemns war among nations

and men, an ultimate theocratic war has an important place

in the religion. This war is foreseen as one directed by

Allah which will destroy the enemies of the black people.

After this destruction, which is variously described as a

series of natural disasters, the falling of bombs from a

wheel-shaped plane in the sky or an ultimate war among

nations, black people will live in peace under the guidance

of Allah (Id. at 270, 291-92).

15 The Black Muslim doctrines concerning war can be clearly

traced, moreover, to the Holy Qur’an, translated by Maulana

Muhammad Ali, which was submitted by petitioner as Exhibit C

at the Special Hearing (A. 41a). This version of the Qur’an

views war as an evil that can only be justified when it is necessary

to defend Muslims against religious persecution. See Maulana

Muhammad Ali, Translation of the Holy Qur’an 2 :190, 2 :191,

2 :216, 2 :217 and commentary at pp. 80-81, notes 238, 239, pp.

90-91, note 277 (5th ed. 1963).

32

In support of its interpretation that the doctrines of the

Nation of Islam only preclude participation in war on

behalf of the United States, the Department relies almost

entirely upon the article of the Muslim faith that states:

“We believe that we who declare ourselves to be righ

teous Muslims, should not participate in wars which

take the lives of humans. We do not believe this nation

should force us to take part in such wars, for we have

nothing to gain from it unless America agrees to give

us the necessary territory wherein we may have some

thing to fight for” (A. 120a).

The only thing that is clear about this statement is its

absolute opposition to participation in wars which take

human lives. The rest of the passage is ambiguous; it can

be read simply as a statement of the fact that Muslims

do not benefit from wars fought by the United States be

cause they have no stake in the country; it can be read as

suggesting that if the Muslims were given some territory

there might be some circumstances under which they would

fight; or it can be read as saying that Muslims would even

fight on behalf of the United States if they were given some

territory.

But even if it is read as suggesting the possibility of

a future willingness of Muslims to fight under some cir

cumstances, there is no indication that even under such

circumstances they would participate in a war that was

inconsistent with the teachings of their faith or that would

be considered “war” within the meaning of §6(j). Thus,

fighting without weapons in self-defense, in defense of

friends and co-religionists, or in defense of community

would neither violate their religious scruples nor disqualify

them from the exemption. See United States v. Owen, 415

F.2d 383, 390 (8th Cir. 1969); United States v. Haught on,

33

413 F.2d 736, 742 (9th Cir. 1969); United States v. Purvis,

403 F.2d 555, 563 (2d Cir. 1968); Taffs v. United States, 208

F. 2d 329, 331 (8th Cir. 1953), cert, denied, 347 U. S. 928

(1954); Shepherd v. United States, 217 F.2d 942, 944 (9th

Cir. 1954). Moreover, the inference that Muslims might

fight at some time if they were given territory is even

more speculative than the statement of the registrant in

the Owen case that it was possible that he might change

his mind about participating in war if his country were

invaded (415 F.2d at 390). Here, as in Owen, the statement

relates to a contingency and cannot supply a basis in fact

for denial of a conscientious objector exemption (Ibid).

And the possibility of the Muslims fighting for territory

that the United States has given them is at least as un

likely an eventuality as the theocratic war that this Court

considered too far removed from Congressional intent to

be considered “war” within the meaning of the Act in

Sicurella v. United States, 348 U. S. 385 (1955).

The only other basis for the Justice Department’s con

clusion that petitioner only objected to participating in

war on behalf of the United States are the statements

attributed by the FBI resume to Elijah Muhammad and

two co-religionists that the teachings of the Nation of

Islam precluded petitioner “ from participating in any form

in the military service of the United States” (A. 120a).

But it is sheer sophistry to argue that this statement

(which is clearly correct) implies that the teachings of

the Nation of Islam do not preclude Muslims from fighting

for some other nation. Moreover, it is patently absurd to

attribute such doctrinal significance to the wording of

a summary of FBI reports which were based on field

interviews by agents (R.P. vol. I l l 252-53). Indeed, the

Justice Department was being less than candid when it

gave such weight to this particular phrase while at the

34

same time it ignored statements in the same context

that were inconsistent with its conclusion. Thus, Elijah

Muhammad is reported in the same paragraph of the

resume to have said that petitioner had been advised

“ that no member of the Nation of Islam may bear arms

against anyone” (A. 149a), and that he believed that peti

tioner was sincere “ in his objection to any form of mil

itary service” (A. 148a) (Emphasis added). Similarly, the

Department overlooked the statements by co-religionists

that petitioner would not “violate the tenets of this teach

ings [Nation of Islam] by engaging in military service”

(A. 150a); that because of his practice of the teachings

of Elijah Muhammad, petitioner is “completely sincere in

his claim of conscientious objector to military service”

(A. 152a-153a); and “ that war, killing and violence are

wrong and in direct contradiction to these teachings” (A.

153a).

It is apparent that none of the specific references to

Muslim doctrine or writings can support the Department’s

conclusion that they precluded only participation in wars

on behalf of the United States. Rather, the Department

based its conclusion upon its view that the Muslims’ op

position to participation in war was primarily motivated

by their hostility toward the United States government.

Thus, the Department interpreted the writings of Elijah

Muhammad to express the “ essential” views of the Black