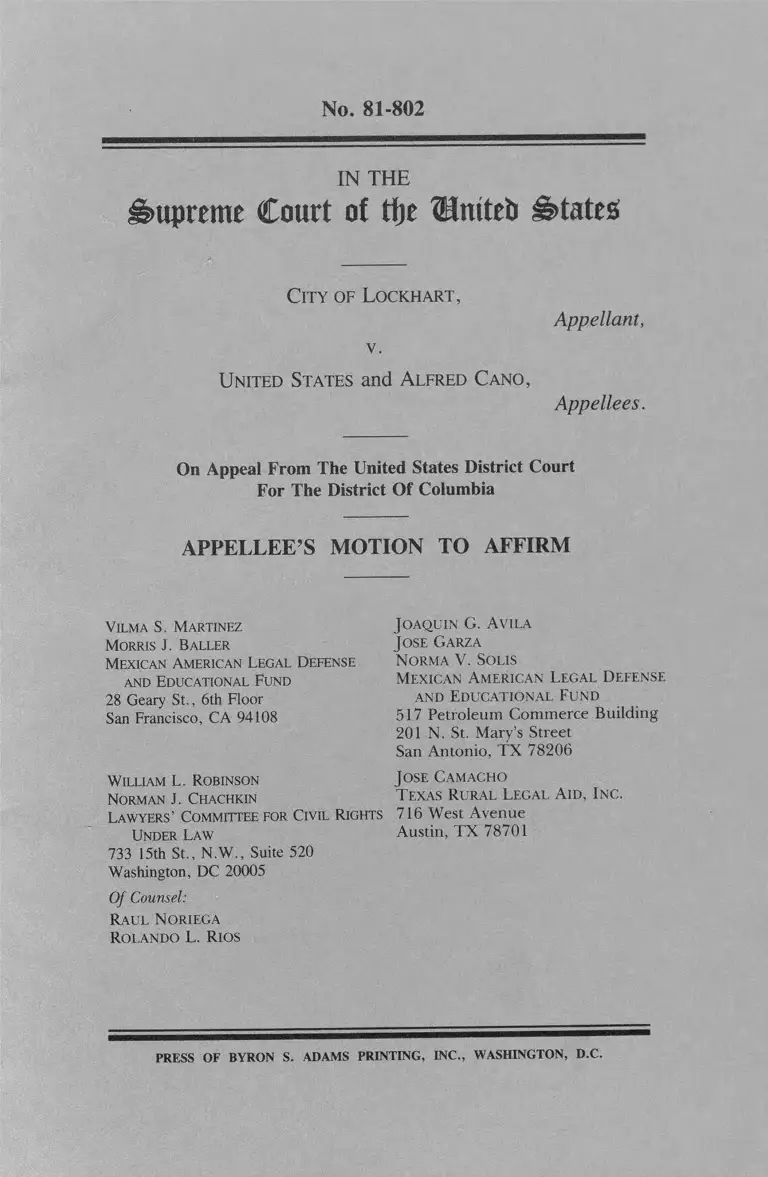

City of Lockhart v United States and Alfred Cano Appellee's Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

December 30, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Lockhart v United States and Alfred Cano Appellee's Motion to Affirm, 1981. 974c2e7f-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c596b9e4-e89a-4ed6-b384-a3f573a216ca/city-of-lockhart-v-united-states-and-alfred-cano-appellees-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

No. 81-802

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfte Hmtefo H>tateg

City of Lockhart,

v.

Appellant,

United States and Alfred Cano,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The District Of Columbia

APPELLEE’S MOTION TO AFFIRM

Vilma S. Martinez

Morris J. B alter

Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

28 Geary St., 6th Floor

San Francisco, CA 94108

William L, Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law

733 15th St., N.W., Suite 520

Washington, DC 20005

Of Counsel:

Raul Noriega

Rolando L. Rios

J oaquin G. Avila

J ose Garza

Norma V. Solis

Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

517 Petroleum Commerce Building-

201 N. St. Mary’s Street

San Antonio, TX 78206

J ose Camacho

T exas Rural Legal Aid , Inc .

716 West Avenue

Austin, TX 78701

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS PRINTING, INC., WASHINGTON, D.C.

INDEX

Page

Table of Authorities.................. ii

Statement of the Case.................. 2

ARGUMENT.... ...................... .11

I. LOCKHART FAILED TO CARRY

ITS BURDEN TO PRECLEAR

ELECTION CHANGES COVERED

BY SECTION 5.................. 11

A. The Numbered Post

System And The Staggered

Terms Provision Were

Changes Subject to

Section 5 Preclearance...11

B. Both The Numbered Post

System And The Staggered

Terms Provisions Have

Discriminatory Effect

On Mexican American

Voters................... 24

II. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DENIAL

OF PRECLEARANCE DID NOT

INTERFERE WITH LOCKHART'S

USE OF OTHER VALID PROVISIONS

OF THE HOME RULE CHARTER.....27

Conclusion 29

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Allen v. Board of Elections,

393 U.S. 544 (1969).................... 13

Beer v. United States,

425 U.S. 130 (1976)........ 3,16,17,19,26

Berry v. Dole,

438 U.S. 196 (1978).................... 23

Briscoe v. Bell,

432 U.S. 404 (1977)................. 12,13

Cano v. Chesser, No. A-79-CA-0032

(W.D. Tex. Mar. 2, 1979)......... ......3

Chapman v. Meier,

420 U.S. 1 (1975)... ....................7

City of Rome v. United States,

446 U.S. 156 (1980)..................15,23

Davis v. Coffee City, Texas,

356 F. Supp. 550 (E.D. Tex. 1972).......4

Perkins v. Mathews,

400 U.S. 379 (1971)...............13,20,22

Phillips v. Walling,

324 U.S. 490 (1975)........ 13

United States v. Board of Commissioners

of Sheffield, Ala.,

435 U.S. 110 (1978)........ 13,15,20,21,22

Page

Weaver v. Muckleroy,

Civ. No. 5524 (E.D. Tex. 1975) .15

-in-

Page

White v. Regester,

412 U.S. 855 (1973)

Statutes

42 U.S.C. § 1973(c)............

Art. 1158, Texas Rev. Civ. Stats

Home Rule Charter of the City

of Lockhart, Section 3.01......

Home Rule Charter of the City

of Lockhart, Section 11.07.....

Other Authorities

S. Rep. No. 94-295 (1975),

2 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin-News,

94th Cong., 1st Sess..... 12,13,14,15,19

H.R. Rep. No. 94-196 (1975),

94th Cong., 1st Sess.........

Testimony of Asst. Atty. Gen.

j. Stanley Pottinger at the

Hearings of H.R. 939, et al,

94th Cong., 1st Sess.(1975).

passim

___ 4

17,18

20

No. 81-802

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF

THE UNITED STATES

October Term,1981

CITY OF LOCKHART,

Appellant,

vs .

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

and

ALFRED CANO,

Appellees.

On Appeal From the United

States District Court For

The District of Columbia

APPELLEE'S MOTION TO AFFIRM

Appellee, Alfred Cano, pursuant to

Rule 16(c) of the Rules of the Supreme

Court, moves the Court to affirm the

District Court's July 30, 1981 Order dis

missing this case. In this declaratory

judgment action, Appellant City of Lockhart

-2-

sought approval of the election provisions

of its Home Rule Charter pursuant to the

Section 5 preclearance provisions of the

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973(c).

The District Court denied preclearance for

reasons set out in its Memorandum Opinion

entered July 30, 1981. The District Court

decision is based upon well established

precedent and thus no substantial question

on the merits has been raised in this

appeal. Since there is no need for further

argument, the judgment should be affirmed

for the reasons set out in this motion.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The City of Lockhart initiated this

action pursuant to Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973(c), on Febru

ary 2, 1980.^ Lockhart sought a declara

tory judgment that a 1973 Home Rule Char

ter altering the City's form of government

and election structure was not adopted

pursuant to a discriminatory purpose and

did not discriminate on the basis of race,

color or membership in an applicable

^Prior to the commencement of this

action, in proceedings initiated by private

litigants, the United States District Court

for the Western District of Texas determ

ined that the adoption of the Home Rule

-3-

language minority group. (R. Complaint

2for Declaratory Relief) In this action,

the City has the affirmative duty of

demonstrating the absence of discrimination

in both purpose and effect. Beer v. United

States, 425 U.S. 130, 140-141 (1976).

Prior to February 20, 1973, the City

of Lockhart, as a Texas general law city,

was governed by a commission form of gov

ernment. (App. 4a) A general law city in

Charter was subject to the Section 5 pre

clearance provisions of the Voting Rights

Act and enjoined the City from utilizing

the unprecleared election change. Cano v.

Chesser, No. A-79-CA-0032 (W.D. Tex. Mar.

2, 1979). Contrary to Appellant's asser

tion, the Court order in Cano did not pre

clude the use of the prior governance in

subsequent city elections. Following the

Texas District Court's determination, the

City of Lockhart submitted the Home Rule

Charter to the Attorney General for Section

5 review. The Attorney General interposed

a letter of objection to the Home Rule

Charter election provisions on September

14, 1979.

2Citations m the form of "R.____" are

to documents in the record, as specified.

Citations in the form of "App.___are to

the opinion of the three-judge District

Court below, reprinted in the Appendix to

the Jurisdictional Statement.

-4-

Texas has the authority to govern itself

only in the manner specifically authorized

by Texas law, Davis v. Coffee City, Texas,

356 F. Supp. 550, 554 (E.D. Tex. 1972).

The City of Lockhart thus had no control

over the size of its governing board or

the method of election of that board.

(App. 3a) Texas law requires that the

commission consist of three members, a

mayor and two commissioners. (Art. 1158

Tex. Rev. Civ. Statutes) Moreover, state

law does not authorize election features

such as single member districts, numbered

posts, residency districts, staggered

terms, or majority vote requriements. (Id.)

Contrary to state law, however, until

1973 the City of Lockhart had required

candidates for election to the commission

to designate the "post" to which the can

didate sought election. (App. 4a)

The Home Rule Charter in 1973 expanded

the authority of the governing body by

providing for a council-manager form of

government. The council consisted of a

mayor and four council members. In adopting

Home Rule status, the City of Lockhart had

the opportunity to choose any of a number

of election schemes, including "pure" at-large

elections. (App. 4a) Instead, the new

-5-

Cliarter' s election provisions called for

at-large election to the council with a

numbered post provision and staggered

terms for councilmanic candidates, with elec

tions for two council members in each year.

The District Court tried this case on

the merits on September 10 and 11, 1980.

After a day of trial, the District Court

limited the evidentiary presentation to

the issue of discriminatory effect. (App.42a) To rebut the City's evidence, Appel

lees introduced evidence concerning the

discriminatory effect of the numbered place

system and staggered terms in the context

of the racially polarized voting patterns

which are prevalent in Lockhart. This

evidence is summarized below. 3 4

3Intervenor Cano was allowed to inter

vene as a party defendant on May 7, 1980,

and participated in the trial.

4As previously mentioned, p.2 supra,

the City is under a duty to demonstrate

the absence of both discriminatory purpose

and effect with respect to the adoption and

maintenance of the Home Rule Charter. A

failure to meet either branch of this dual

burden requires denial of the requested

declaratory judgment. Consequently, in

order to facilitate the consideration of

this case and to save judicial resources,

the Court bifurcated the trial and heard

evidence only on the question of discrim

inatory effect. (App. 2a)

-6

Although the population of Lockhart

is well over half minority--including

approximately 41% Mexican Americans and

14% blacks (App. 3a)--minorities have his

torically been excluded from Lcokhart1s

governing body. No minority candidate had

ever won election to the Board of Commis

sioners before 1973 and the only one elec

ted to the Council since the 1973 Charter

change owed his success to an unusual frag

mentation of the vote for Anglo candidates.

c:(App.7a) Trial testimony showed that

Lockhart’s minority communities could not

elect candidates of any race who would

serve their minority interests, and that

governing board members were therefore able

to ignore minority needs, and did. (R.

Rangel Deposition, pp. 9-11, 19, 21-22)

A strong pattern of racial bloc voting

characterizes elections in the City of

Lockhart. Lockhart does not deny the exis

tence of polarized voting, and all members

of the panel of the Court below found such

a pattern. (App. 6a, 24a) Election returns

from municipal elections since 1973 show

a close correspondence between Spanish-

°Four different Anglo candidates opposed

the lone Mexican American, Mr. Rangel, in

the 1978 election. Although the four

-7

surnamed voters who voted in the particular

election and the number of votes received

by the Mexican American candidate, indi

cating that Anglo voters do not vote for

6Mexican American candidates.

The Home Rule Charter adopted in 1973

included two specific features in Lockhart's

city elections which have the effect of

diminishing minority voting strength:

numbered posts and staggered terms. The

discriminatory effect of both features

results partly from their tendency to re

duce or eliminate the successful use of

"single shot" voting by minorities. As

both the majority opinion and the dissent

below noted, such voting constitutes an

effective means for numerical and racial

minorities to avoid their "submergence"

which ordinarily accompanies at-large

election schemes, Chapman v. Meier, 420

U.S. 1, 16 and n. 10 (1975), especially

in the context of racially polarized

voting, White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755,

766-69 (1973). (App. 7a-8a, 25a and n.

29)

gathered twice as many votes as Rangel, no

one of them outpolled him. (R. Def. Exh. 14)

In 1978, the three Hispanic candidates

(one for Mayor and two for council

-8-

The imposition of numbered posts

reduced the field of candidates and at the

same time highlighted the racial identity

of individual candidates for each position.

Given Lockhart's pattern of racially polar

ized voting, this racial highlighting ex

posed the minority candidates to racially

biased bloc voting opposition. (R. Rangel

Deposition, p. 22; Trial Transcript, pp.

247-249) The imposition of a numbered

place system also nullified the advantages

of single-shot voting for minorities by

reducing its impact. (R. Trial Transcript,

p. 139) That impact will be much greater

when the single minority beneficiary com

petes against a larger number of Anglo

candidates for a number of seats, rather

than a smaller number for a single numbered

7place. (R. Trial Transcript, pp, 138-40)

All these factors were operative in Lock

hart .

positions) received 655 votes, 642 votes,

and 602 votes respectively, in an election

in which 660 Hispanics voted (out of 1,993

voters). (App. 7a, R. Def. Exh. 14) In 1973,

417 Mexican American voters went to the

polls; the two Mexican American candidates

received 445 and 401 votes. (R. Def. Exh.

14) In 1977, when 233 Mexican Americans

voted, the Mexican American candidate for

Place 3 received 251 votes. (Id.)

7Mr. Bernard Rangel's testimony indicates

-9-

The adoption of staggered terms also

adversely affected minority voting strength

in Lockhart. By limiting the number of

seats open for election in a given year,

staggered terms highlighted and increased

the visibility of a particular race, and

thus enhanced the likelihood of racial

targeting against candidates. (R. Trial

Transcript, p. 149) They also had the

effect of creating lower voter turnout,

which the evidence showed disproportion

ately and adversely affected minority

8voters. (R. Trial Transcript, pp. 256-58)

The discriminatory effects of numbered

places and staggered terms in Lockhart are

seen in the electoral record since 1973.

Seven Hispanics have run for the Commission

since 1973; yet, only one Mexican American

has been elected, in unusual circumstances

involving a close four-way split of the * 8

that his race for City Council in 1973

became a head-to-head contest with an

Anglo candidate as a result of the place

system. Moreover he testified that with a

numbered post system "...the political sys

tem is still going to throw you the best

[opposition]..." and thereby target a min

ority candidate. (Rangel Deposition, pp.

21- 22)

8Voter turnout data for the 1974 and

1977 elections, which were held subsequent

to the adoption of the Home Rule Charter,

-10-

Anglo vote. (See p. 6 , n. 5, supra) In

deed, in that same election, two other

Mexican American candidates lost because

their advantages of single-shot voting

support were insufficient to prevail against

Anglo voting support that was divided among

"only" three non-minority candidates. (App.

7a, R. Def. Exh. 14)

After considering this evidence, the

District Court found that Appellant had

failed to show that the numbered post and

staggered term provisions of the Home Rule

Charter lacked discriminatory effect; on

the contrary, it found that those features

had a discriminatory effect on Lockhart's

Mexican American voters. (App. 16a) Be

cause in the view of the majority those

features were changes in election laws sub

ject to Section 5 preclearance, declaratory

judgment was denied. (App. 16a-17a) The

objection issued earlier by the Attorney

General therefore remains in effect, blocking

further use of those features of the election

show that low voter turnout adversely af

fects Mexican American candidates. In 1977,

24% of Mexican Americans and 36% of other

registered voters cast ballots. But in

1975, when only 176 ballots were cast in

uncontested City elections, only 10 or

5.7% were cast by Mexican American voters.

(See R. Def. Exh. 14)

-11-

. 9system.

ARGUMENT

I. LOCKHART FAILED TO CARRY

ITS BURDEN TO PRECLEAR

ELECTION CHANGES COVERED

BY SECTION 5.

The decision below correctly held

that both the numbered post system and

the staggered terms introduced by the 1973

Home Rule Charter were changes in election

practices subject to Section 5 preclear

ance. It further agreed with the Attorney

General's earlier determination that those

changes had a discriminatory effect on

minorities and therefore could not be pre

cleared. These rulings were plainly

correct, and present no substantial issues

for review.

A. The Numbered Post System And

The Staggered Terms Provision

Were Changes Subject To Sec

tion 5 Preclearance.

At the threshhold, Lockhart argues that

the numbered post provision was not subject

to preclearance under Section 5 of the

^The Attorney General's letter of ob

jection does not purport to suspend the

operation of the City's entire Home Rule

Charter, cf. Appellant's Jurisdictional

Statement, pp. 14-15, but only the

offensive election changes. (R. Def. Ex

12, p. 2)

-12-

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c.

(Lockhart does not contest the applicabil

ity of Section 5 to the staggered terms

provision.) The Court below correctly

held that both features of the Charter

were election law changes requiring sub

mission and preclearance.

1. Under Section 5, a covered polit

ical subdivision in Texas must submit to

the United States Attorney General or to

the United States District Court for the

District of Columbia all changes in elec

tion laws or practices since November 1,

1972, and must obtain a determination that

such election changes were not adopted pur

suant to a discriminatory purpose and do

not discriminate on the basis of race,

color or membership in an applicable lang

uage minority group. Briscoe v. Bell,

432 U.S. 404 (1977) .

Congress crafted Section 5 to provide

a comprehensive framework for federal scru

tiny of election practices in covered juris

dictions which might have the purpose or

effect of discriminating against minority

voters. In extending Section 5, Congress saw

it as "the front line of defense against

voting discrimination," S. Rep. No. 94-295

(1975), 2 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News,

-13-

94th Cong., 1st Sess., 774, 784 (1975).

At the same time, Congress took specific

and approving note of the broad reading

given Section 5 by the Supreme Court in

Allen v. Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544,

566 (1969), which held that section should

be given the "broadest possible scope,"

and in Perkins v. Mathews, 400 U.S. 379,

387 (1971), which reiterates Allen1s hold

ing that all changes, no matter how minor,

are covered by the preclearance require

ment. See, S. Rep. 94-295, supra, p. 782;

H.R. Rep. No. 94-196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1975), p. 9.10 Legislation which embodies

a powerful remedial intent, so clearly ex

pressed and reconfirmed by Congress, should

not be hamstrung by narrowing technical

constructions. See, Briscoe v. Bell,

supra, 432 U.S. at 410; United States v.

Board of Commissioners of Sheffield, 435

U.S. 110, 124 (1978); Phillips v. Walling,

324 U.S. 490, 492 (1975).

Congress specifically intended Section

5 to stand as a safeguard against discrim

inatory use of at-large elections, numbered

post systems, and staggered terms the

1-0 This Court reasserted its steadfast

view of Section 5's comprehensive scope

in United States v. Board of Commissioners

of Sheffield, Ala, 435 U.S. 110, 122 (1978).

-14-

essential elements of the election system

embodied in Lockhart's 1973 Home Rule

Charter. Congress extended Section 5 to

cover Texas in large part because

[t]he at-large structure, with

accompanying variations of the

majority run-off, numbered

place system, is used exten

sively among the 40 largest

cities in Texas .... These

structures effectively deny

Mexican American and black

voters in Texas political

access ....When numbered posts

are combined with a majority

vote requirement, the change

for a minority candidate be

comes practically impossible

unless minorities are in a

voting majority.

S. Rep. No. 94-295, supra, p. 794 and n.

17; H.R. Rep. No. 94-196, supra, p. 19 and

n. 21. In documenting the need for Section

5's extension to Texas, both House and

Senate Committees reported with concern on

local Texas jurisdictions' discriminatory

use of staggered terms and numbered place

systems, S. Rep. No. 94-295, supra, pp.

783, 794; H.R. Rep. No. 94-196, supra, pp.

10, 18-19. Both Committee reports cite

with approval a federal court decision

nullifying as discriminatory, on constitu

tional grounds, a 1972 City Charter con

version by the City of Nagodoches from an

-15-

at-large commission form of government to

a numbered place system,10 while noting that

Section 5 is needed to replace just such

time-consuming and expensive constitutional

litigation. See S. Rep. No. 94-295, supra,

pp. 793, 777-78; H.R. Rep. No. 94-196, supra,

pp. 19, 4-5. In short, it is clear that

Congress extended Section 5 to cover Texas

for the express purpose of subjecting to

federal scrutiny systems like that adopted

by Lockhart in 1973.

2. This Court has firmly established

that Section 5 requires scrutiny of election

changes which substitute home rule govern

ment for general law government, United

States v. Board of Commissioners of Sheffield,

supra, and of changes to numbered posts and

staggered terms in a jurisdiction which uses

at-large elections characterized by racial

bloc voting, City of Rome v. United States,

446 U.S. 156, 183 (1980).11 See also, White

v . Regester, 412 U.S. 855, 766 (1973) (finding

of constitutional violation in Texas at-large

system based in part on the use of numbered posts).

10Weaver v. Muckleroy, Civ. No. 5524

(E.D. Tex. 1975)

llrThe Court in Rcme attributed much of the dis

criminatory effect of these election practices to

their undermining of single-shot voting by minorities.

446 U.S. at 184 and n. 19.

-16-

Appellant seeks to evade these holdings by

arguing that there was no post-1972 "change"

to trigger Section 5 review, relying on

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130, 138-39

(1976) .

Appellant argues that preclearance was

unnecessary for the numbered place system

because Lockhart utilized a numbered place

12system prior to November 1, 1972 in a

different form and as part of a different

election system for a different number of

positions. Appellant also asserts that the

illegality of its use of a numbered place

system prior to the adoption of the Home

13Rule Charter is irrelevant to the issue

of Section 5 coverage. (Jurisdictional

Statement, pp. 9-10)

In Beer v. United States, supra, this

Court held Section 5 inapplicable to an

election system, in existence since 1956,

which continued in effect without change

12In Texas, those laws affecting voting

which were enacted prior to November 1, 1972

are exempt from Section 5 preclearance.

42 U.S.C. § 1973(c), Beer v. United States,

supra.

13The District Court majority found that

Lockhart's use of numbered places before

1973 was illegal under Texas law, App. 11a-

13a, and Appellant has not challenged that

finding here.

-17-

or re-adoption after Section 5 became

applicable. The ordinance under scrutiny

in Beer was a post-census redistricting for

the City of New Orleans which changed the

boundaries of five single member districts

but did not alter, or even refer to, the

City's two at-large districts. This Court

concluded that the at-large districts, al

though potentially discriminatory, were

beyond Section 5's reach because they had

"existed without change since 1954," 425

U.S. at 139.

Appellant's reliance on the Beer hold

ing is misplaced. Lockhart's enactment of

a new Charter in 1973 providing for a num

bered post system constituted a "change"

which triggers Section 5 coverage. Prior

to 1973, Lockhart's use of numbered posts

was ultra vires and therefore, under Texas

law, void. (App. 12a-13a) With the adop

tion of the Home Rule Charter, the City

affirmatively adopted a lawful numbered

place system for the first time. See, 1973

Home Rule Charter, Section 3.01. (R. Def.

Exh. 7) The legalization of the numbered

post feature was a significant change. The

adoption of a Home Rule Charter, valid under

State law, which included the numbered post

system, foreclosed to the minority commun

-18-

ity of Lockhart a state-law challenge to

that discriminatory election feature, which

would otherwise be available. In contrast,

New Orleans' redistricting ordinance did

not mention the at-large districts; and

indeed, not an ordinance but a referendum

would have been required to change the New

Orleans City Charter.^ Moreover, in New

Orleans, the redistricting did not change

the governing structure, of which the at-

large seats were a part, in any way. How

ever, Lockhart's Home Rule Charter fundamen

tally changed the form of government in

which the numbered place system operated.

It increased the number of such places from

two to four and changed the places from

Commissioners' seats in a commission form

of governance to council members' positions

in a mayor-council-manager form of govern

ment .

3. The numbered place system incorporated

in Section 3.01 of the Charter is covered

even if it did not, standing by itself,

change the actual (although unauthorized)

prior practice. The numbered place system

14Lockhart could have chosen a number of

other election systems (e.g., by-district,

pure at-large, etc.) for its Home Rule

Charter, but chose in 1973 to utilize num

bered places. New Orleans' ordinance did

and could not modify the form of elections.

-19-

was a part of a larger election and gov

ernance system which was comprehensively

changed. Congress specifically intended

that such overall changes in governance

would trigger scrutiny of specific aspects

of the governance system. As the 1975

Senate Committee Report noted,

In some Section 5 cases, a change

in the voting practice or pro

cedure may also retain some features

of the previous system, and all

aspects of such a change are

within the reach of Section 5.

S. Rep. No. 94-295, supra, p. 19 (emphasis

15supplied). Such an application of Section

5 is consistent with the procedures adopted

by the Attorney General in his administra

tion of Section 5. Department of Justice

officials, in testifying before Congress in

connection with the 1975 extension of Sec

tion 5, introduced an exhibit which indi

cates a policy of objection to changes in

governance where specific features in the

15The Report cites with approval the

District Court decision, 374 F. Supp. 363

(D. D.C. 1974), reversed in Beer, supra.

This Court's reversal does not undercut the

importance of the quoted passage. The error

below in Beer was that there was no change

in any "voting practice or procedure"; the

Senate Committee's citation was therefore

inapposite to its clear purpose as stated

in the text.

-20-

change were objectionable. See testimony

of Assistant Attorney General J. Stanley

Pottinger at the Hearings of H.R. 939, et

al., before the Subcommittee on Constitu

tional Rights, House Committee on the Ju

diciary, 94th Congress, 1st Sess., 166

(1975). Although the Attorney General's

application of Section 5 is not binding on

this Court, the Court has given great def

erence to the interpetation of Section 5

made by the Attorney General, Perkins v.

Matthews, supra, 400 U.S. at 390-394, par

ticularly where Congress has manifested its

approval of the Attorney General's inter

pretation, United States v. Board of

Commissioners of Sheffield, supra, 435 U.S.

at 131-32. The Attorney General's letter

of objection to the numbered place pro

vision of the Lockhart City Charter was

fully consistent with an administrative

* 1 7policy approved by Congress.

^Exhibit 5 indicates several instances

of Section 5 coverage and objections to

the change in form of government as well

as to specific features of the election

change, i.e., Conyers City, Ga.; Lancaster

County, South Carolina; and Charleston Co.,

South Carolina.

17In his letter of objection of Sep

tember 14, 1979 (R. Def. Exh. 12), the

Attorney General clearly based Section 5

-21-

This Court's decision in United States

v. Board of Commissioners of Sheffield,

Ala.., supra, supports the District Court's

analysis. In Sheffield, the City of

Sheffield, by referendum held in 1975, al

tered its form of government from a com

mission form of government in which three

commissioners were elected at-large, to a

mayor-council form of government in which

eight aldermen were to be elected at-large,

by numbered posts. 435 U.S. at 114-15.

The Attorney General then objected that

while he did not interpose any

objection to the change to a

mayor-council form of govern

ment... to the proposed district

lines or to the at-large elec

tion of the mayor and the presi

dent of the council, he did ob

ject to the implementation of

the proposed at-large method of

electing city councilmen because

he was unable to conclude that the

at-large election of councilmen

required to reside in districts

will not have a racially discrim

inatory effect.

Id., 435 U.S. at 116. The Supreme Court

sustained the Attorney General's objection.

The similarities in the facts of the pres

ent case and those in Sheffield are quite

coverage on the fact that in adopting the

Charter, Lockhart had altered its form of

government and voluntarily adopted the

entire election scheme in the Charter.

-22-

striking. In both instances the Attorney

General and the District Court found ob

jectionable a change in governance which

included an election feature in use both

before and after the change in the form

of governance— in Sheffield, the at-large

system, and in Lockhart the numbered post

system. Thus the District Court was correct

in simply adhering to a well-established

application of Section 5 in reviewing the

election features of a change in govern

ance .

4. Appellant contends that this

Court's decision in Perkins v. Matthews,

supra, makes the illegality of Lockhart's

pre-1973 use of numbered places irrelevant.

In -Perkins the Court examined an at-large

system which was required by state law

prior to the effective date of Section 5,

but only implemented after that date. The

Court, looking to the practice actually "in

force or effect" prior to Section 5, held

that implementation of the state law was a

change covered by Section 5, 400 U.S. at

395. In so doing, the Court served Cong

ress' purpose to assure broad Section 5

coverage of discriminatory election prac

tices. It should not now turn Perkins on

its head to circumvent that same purpose,

and need not do so, since as demonstrated

above Lockhart did adopt election changes

in 1973.

Under Section 5, failure to secure

preclearance simply leaves a covered change

unenforceable, 42 U.S.C. § 1973(c), Berry

v . pole, 438 U.S. 196 (1978). The sub

mitting jurisdiction must, in the absence

of preclearance, revert back to the former

election scheme. City of Rome v. United

States, supra, 446 U.S. at 182. The proper

test of whether there has been a change

affecting voting is whether, upon such

reversion, the election scheme of the pol

itical subdivision would differ from that

submitted for preclearance. In the instant

case, Lockhart could not lawfully revert to

use of a numbered post system in the absence

of preclearance of Section 3.01 of its Home

Rule Charter, since state law, absent a

valid Home Rule Charter, does not authorize

use of such a system. Absent preclearance,

Lockhart's would be a pure at-large system,

without posts. See pp. 4, 17, supra. There

fore the Home Rule Charter provision for

numbered posts did change Lockhart's elec

tion practices.

-23-

-24-

B . Both The Numbered Post System

And The Staggered Terms Pro

visions Have Discriminatory

Effect On Mexican American

Voters.

The District Court correctly found

that both the numbered post system and

the staggered terms provision "had and

will continue to have" a discriminatory

effect on Mexican American voters, in that

it diminishes their ability to elect can

didates of their choice. (App. 16a)

Appellant does not contest the Court's

finding as to staggered terms. Lockhart

concedes that staggered terms may have a

discriminatory effect, but argues that

such effect is hypothetical in its case

(Jurisdictional Statement, pp. 12-15).

Apart from the point that this local fac

tual issue presents no substantial question

warranting exercise of this Court's juris

diction, Lockhart's position is unfounded;

the Court's finding is amply supported in

the record.

The testimony of the Appellant's

expert witness, Dr. Dalbert Taeble, reveals

that the effect of staggered terms is

generally to decrease voter turnout. (R.

Trial Transcript, pp. 83-84) According to

Dr. Fred Cervantes, Appellee's studies of

-25-

voter turnout show that low voter turnout

has a disproportionate effect on minority

voters. When turnout is low, generally,

turnout among minority voters is even

lower. (See p. 9 and n. 8 , supra.) Voter

turnout data made available by the City of

Lockhart demonstrates that low voter turn

out disproportionately affects minorities.

1 R(R. Def. Exh. 14)

Staggered terms also have an adverse

effect on the voting strength of minor

ities by facilitating the targeting of

minority candidates. Testimony at trial

revealed that staggered terms operate in

the same discriminatory fashion as a num

bered post provision in the context of

racially polarized voting. (R. Trial

Transcript, pp. 81,83,148,149) In Lock

hart staggered terms have in fact had the

effect of exacerbating racial tactics used

19against minority candidates. (Id. p. 245)

18See pp. 9-10, n. 8, supra.

1 9During the 1978 race an advertisement

ran in the local paper which purported to

link the three Mexican American candidates

to the controversial Chicano political

party, Raza Unida Party. (R. Def. Exh. 15)

Mr. Bernard Rangel, in his deposition,

testified that such a tactic was meant to

arouse the white Anglo vote against the

-26-

The staggered terms provision did,

therefore, bring about a "retrogression"

in the political strength of Mexican

American voters, as required by Beer v.

United States, supra, 425 U.S. at 141.

The retrogression is caused in at least

two ways. First, the staggered terms are

an integral part of a larger election

change which, in the aggregate, signifi

cantly diluted minority voting strength,

see p. 19 , supra. Second, the addition

of two elections in odd-numbered years

adversely affects minority voting in

previously-scheduled, even-year elections,

by creating more numerous and frequent

elections, which exacerbates the phenomenon

of low minority voter turnout. The mini

mal positive effect of the expanded number

of seats does not offset this additional

obstacle to minority voters' strength.

(R. Trial Transcript,pp. 169-170) Appellant

had the burden of demonstrating that the

addition of staggered terms would not be

retrogressive. Both the Attorney General

and the District Court were properly un

persuaded.

three Mexican American candidates. (R. Def.

Exh. 15, Rangel Dep. pp. 25-26) The re

sulting turnout was in fact the greatest of

any post-Charter election (Def. Exh. 14),

and all three candidates were defeated.

-27-

II. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DENIAL

OF PRECLEARANCE DID NOT

INTERFERE WITH LOCKHART'S

USE OF OTHER VALID PROVISIONS

OF THE HOME RULE CHARTER.

Appellant also challenges as excessive

the scope of the District Court's order

denying declaratory judgment. Appellant

apparently suggests that the District Court

has invalidated its entire Home Rule Charter

(Jurisdictional Statement, pp. 14-15).

That suggestion is misleading. While it is

true that adoption of the Home Rule Charter

triggered Section 5 review, the District

Court limited its review to the effect of

the numbered post and staggered terms pro-

visons. (R. Trial Transcript, pp. 183- 198)

The District Court clearly indicated that

other elements of the Charter were simply

not before the Court for Section 5 review.

(R. Trial Transcript, p. 199) Neither the

trial on the merits nor the District Court's

order addressed the discriminatory effect

of any provision of the Charter, other than

the two discussed at length above. While

Appellant may have construed its suit as a

request for a declaration that all aspects

of the Charter were enforceable, denial of

that judgment does not mean that all aspects

were struck down. In sum, the District

-28-

Court's order cannot be read to invalidate

the entire Home Rule Charter.

This conclusion is further supported

by the fact that the Attorney General in

his review of the submission of the Charter

objected only to the specific election

features and not to the entire Charter.

(Def. Exh. 12, p. 2) Moreover, in response

to a prior submission by the City of Lock

hart of changes in the Charter which in

corporated a majority vote provision along

with a bilingual election provision, the

Attorney General objected to the majority

vote provision while approving the bilingual

elections. (R. Def. Exh. 10, p. 2) Thus

the prior actions of the Attorney General

support the conclusion that both Appellant

and the United States have conducted their

business under Section 5 with the awareness

that Section 5 submissions are ordinarily

limited to election provisions, each of

which is to be assessed separately.

Finally, the Charter itself provides

for the separate review of its provisions.

Section 11.07 of the City of Lockhart Home

Rule Charter reads as follows:

If any section or part of section

of this charter shall be held

invalid by a court of competent

jurisdiction, such holding shall

-29-

not effect the remainder of

this charter.

(R. Def. Exh. 7, p. 31)

Thus, the invalidation of the dis

criminatory election features incorporated

in the Charter do not, by its own terms,

affect the remainder of the Charter.

In view of the foregoing, the change

to a council-manager form of government

and the increase in the size of the gov

erning board as well as other provisions

of the Charter remain in effect. Only the

numbered places and staggered terms are

barred. This limited prohibition does not

intrude inappropriately into the local

management of political affairs beyond the

scope of federal review.

Conclusion

The District Court correctly applied

well-settled Section 5 principles in re

viewing the numbered post and staggered

terms provisions of the Lockhart Home Rule

Charter. Neither the District Court's

Order denying declaratory judgment nor

Appellant's arguments raise any substantial

issues of general importance. Plenary

consideration is therefore unnecessary.

-30-

The District Court's order denying

declaratory judgment should be affirmed.

DATED: December 30, 1981.

Respectfully submitted,

VILMA S. MARTINEZ

MORRIS J. BALLER

Mexican American Legal

Defense and Ed. Fund

San Francisco, Calif.

JOAQUIN G. AVILA

JOSE GARZA

NORMA V. SOLIS

Mexican American Legal

Defense and Ed. Fund

San Antonio, Texas

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Lawyers' Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law,

Washington, D.C.

JOSE CAMACHO

Texas Rural Legal Aid, Inc.

San Antonio, Texas

Of Counsel:

ROLANDO L. RIOS

RAUL NORIEGA