Lawson v. United States of America Opening Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lawson v. United States of America Opening Brief for Appellant, 1948. d7ba5cb6-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c5bc1466-b2d3-4442-bd95-a38b4a8f7f91/lawson-v-united-states-of-america-opening-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

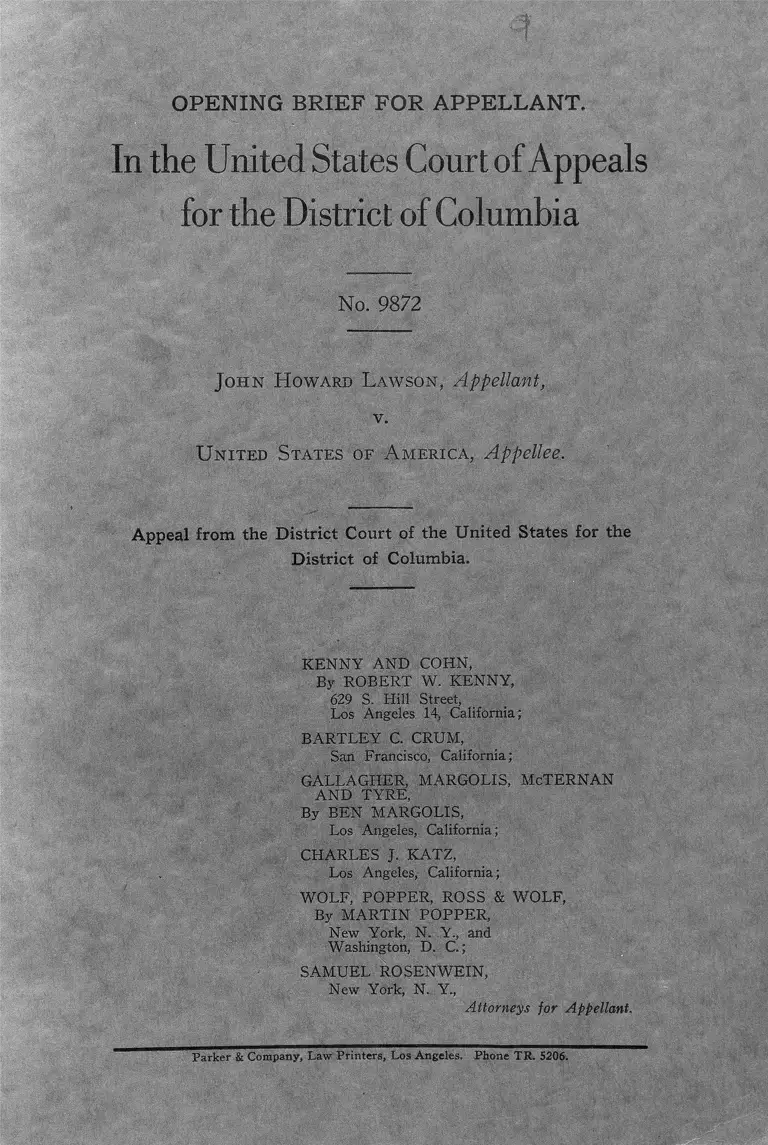

OPENING BRIEF FOR APPELLANT,

In the United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia

No. 9872

J o h n H o w a r d L a w s o n , Appellant,

v.

U n i t e d S t a t e s o f A m e r i c a , Appellee.

Appeal from the District Court of the United States for the

District of Columbia.

KENNY AND COHN,

By ROBERT W. KENNY,

629 S. Hill Street,

Los Angeles 14, California;

BARTLEY C. CRUM,

San Francisco, California;

GALLAGHER, MARGOLIS, McTERNAN

AND TYRE,

By BEN MARGOLIS,

Los Angeles, California;

CHARLES J. KATZ,

Los Angeles, California;

WOLF, POPPER, ROSS & WOLF,

By MARTIN POPPER,

New York, N. Y., and

Washington, D. C .;

SAMUEL ROSENWEIN,

New York, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Appellant.

Parker & Company, Law Printers, Los Angeles. Phone TR. 5206.

TOPICAL INDEX

PAGE

Jurisdictional statement 1

Statement of the case. 1

Statutes involved 19

Summary o f argument................................

A rgum ent and Statem en t of P oints

19

I.

The particular questions put to the defendant and the ruling

of the court that the Committee could require defendant to

answer, and the conviction for failure to answer, violated

the rights reserved to the defendant under the First, Fourth,

Fifth, Ninth and Tenth Amendments of the Constitution to

be protected from official inquisition that can compel dis

closure of his private beliefs and associations (Point 1 )..... 26

A. The right of association is an extension of freedom of

speech and assembly............................................. ........ ........ 43

B. Freedom to speak and assemble includes the right to do

so privately .................. ........................................................... 45

C. An absolute privilege protect beliefs and associations.— 47

D. Political and trade union as well as religious beliefs

and associations are protected by the Constitution.......... 49

E. Under the facts of this case the freedom from unlaw

ful search and self-incrimination forbids inquiry into

membership in the Communist Party; it is not neces

sary that membership be punishable as a crime in order

to shield the individual from official inquisition into

the fact o f membership.................. ....................................... 50

F. Reaffirmance by the court of the right to privacy of

belief will not impede the lawful functions of Congress 55

II.

No immunity act can remove the right of freedom from-

compulsory disclosure of beliefs and associations, and,

even as to tangible acts, Congress may not now compel oral

testimony because it has not yet provided an immunity act

that is sufficient to meet the standards of completeness re

quired by the Constitution (Point 2 ) ......................................... 56

III.

The trial court erred in refusing to allow proof or to take

judicial notice of the facts showing that the defendant was

denied due process of law by the Committee and in refusing

to give defendant’s proposed instructions on the subject

(Point 3) .................................................. 62

A. The proof offered established that the defendant was

denied due process in that, without authorization of

any law, the Committee sought to and did so conduct

its hearings as to effectuate its purpose of preventing

defendant from continuing in his private employment

and depriving him of other valuable personal liberties

and property rights................................................................. 62

(1 ) The rights of defendant affected by the Commit

tee’s action are protected by the due process clause 62

(2 ) Any governmental action designed and calculated

to deprive a person of any property right or per

sonal liberty protected by the due process clause is

illegal and void, if such deprivation is not specifi

cally authorized by law............................................. 64

(3 ) Such governmental action is illegal and void, no

matter how subtle or indirect it may be, if it re

sults in injury to or invasion o f any right pro

tected by the due process clause................................. 65

ii.

PAGE

111.

B. The proof offered established that the defendant was

denied due process in that, while denying the require

ments of a fair hearing, the Committee so conducted its

hearings as to effectuate its purpose of preventing de

fendant from continuing in his employment and de

priving him of other valuable personal liberties and

property rights ...................................................... ................ 68

IV.

The trial court committed prejudicial error by denying to

the defendant the opportunity to show that this particular

legislative body, in this particular inquiry into alleged

“ subversive” influences in the Hollywood motion picture in

dustry and into the political affiliations o f employees of that

industry, acted in excess of the bounds of its lawful power

and that therefore the defendant could not be required to

answer the questions (Point 4 ) ................................. ................ 72

A. In a contempt proceeding such as this the defendant

may present evidence to establish whether the Com

mittee is pursuing a non-legislative purpose..... .............. 72

B. This particular inquiry into the Hollywood motion pic

ture industry lay entirely outside the lawful bounds

of the power of the House Committee on Un-American

Activities because it constituted an unwarranted inquiry

into the content of motion pictures and into private

employment relationships in a private industry................ 76

C. In this case the court erred in ruling that the Commit

tee had the right to compel defendant to answer ques

tions regarding his political affiliations, because in de

manding answers to those questions the Committee was

acting beyond the scope of any legislative power and

infringing upon the areas reserved to the people by the

Ninth and Tenth Amendments and delegated to the

judiciary by Article Three of the Constitution................ 78

PAGE

IV.

PAGE

V.

The statute creating the House Committee on Un-American

Activities on its face, and as construed and applied, is un

constitutional (Point 5 ) ...................................................—.......... 90

(This point has been left for consideration by this court

in the matter of Trumbo v. United States, No. 9873,

since in that case both political and trade union affilia

tions are involved.)

VI.

The court erred in instructing the jury that the question put

to the defendant, as recited in the indictment, was a perti

nent question (Point 6 ) ......-.........-.......... — .............. .......... ...... 90

A. The question was not pertinent because, for the pur

poses of the committee, it was cumulative...................... 90

B. The question was not pertinent because it was not ma

terially relevant to any inquiry within the scope of the

committee’s stated authority......................................... ........ 92

C. The question was not pertinent because, as framed, it

was not a legally proper question..................................... 93

V II.

The charge of the court that (A ) a non-responsive reply, or

(B ) a reply that seems unclear to the jury is per se con

clusive proof of a refusal to answer, was so erroneous as

to affect the substantial rights of the defendant and thereby

resulted in prejudicial error (Point 7 ) ..................................... 95

V III.

The court committed prejudicial error in invading the prov

ince of the jury by his comments during the course of the

defense argument to the jury (Point 8 ) ...................................100

V.

IX .

The trial court committed prejudicial error in refusing to

permit cross-examination of the principal prosecution wit

ness, J. Parnell Thomas, and in admitting hearsay evidence

to establish pertinency without affording any right of cross-

examination on that evidence (Point 9 ) ...................................103

X.

The trial court erroneously ruled and charged that there was

evidence upon which the jury could conclude that the

chairman of the House Committee on Un-American Activi

ties had inherent power and authority to appoint a validly

constituted subcommittee, and that such a subcommittee was

in attendance at the time that the defendant was sworn and

testified; and the trial court committed reversible error in

failing to charge that the government must prove beyond a

reasonable doubt that a validly constituted subcommittee

was in attendance at the time the defendant was sworn and

testified, and in quashing defendant’s subpoena duces tecum

for the written minutes of the committee, relating to this

issue (Point 10).............................................. ................ ............. 110

X I.

The court erred in excluding defendant’s evidence that the

committee failed to certify to the House of Representatives

all o f the facts relating to his alleged failure to answer an

allegedly pertinent question (Point 11).....................................118

X II.

The trial court erred in denying defendant’s challenge and

motion to dismiss the jury panel (Point 12)........................... 120

(1 ) The scope and purpose of the review herein is estab

lished by virtue of the Appellate Court’s power of

supervision over the administration of justice in the

trial court ...............................................................................124

PAGE

gpj....................................................................................... ............. tioisrtpucQ

gpj............................( n ju iog) umoaj saonp SBuaodqns sguBpuaj

-ap SuiqsBtib ui jojj3 ppiprifajd pajjituuioo jjnoo jeuj aqx

'IIAX

Sid.................................................................. ................... (91 û!°dt)

paiuap Xjsnoauojja 3J3av jbijj avsu b joj uoijoui puB qBjjmb

-OB joj suoijouj ‘juarajoipui aqj ssiuisip oj uoijoui sguBpuajaQ

'IA X

ppj.............-............................................ (g j juiog) aoipnfajd puB

SBiq jo jiABpqje s^uBpuajap aqj jo Suqg aqj Suiavojjoj jps

-unq Xjijenbsip o; asnjaj oj jjnoo jbijj aqj joj jo jja sbav jj

’A X

ggj.............................................. ....... (p j ju io j) sjojnf pasodojd

oj ajip jioa uo suoijsanb jBijajBiu uiBjjao jnd oj juBpuajap

AVOJJB OJ JESUJ3J aqj ( q ) pUB ‘S3Su3||BqO Xj0jdUJ3J3d JBUOIJ

-ippB JUBpU3J3p 3qj JUBJ.§ OJ JBStljaJ 3qj (^ ) pUB ‘3SUB0 JOJ

saaAqdtua juaraujaAoS oj saSuaqBqo sguBpuajap jo piuap

aqj ( g ) puB ‘Amf jbijj sqj SuqpuBdrai ui paXojdma poqjatu

aqj ( y ) jo jjusoj b sb jojjs ppipnfajd pajjituuioo jjnoo aqx

'A IX

l£l....... ............................................... (n ^!°d[) wqomfOD jo

jjnog) joijjsiq sqj iuojj jbuj aqj jajsuBjj oj uoijoui s(jub

-puajap SuiAiap ui jojj3 ppipufajd pajjiuuuoo jjnoj) a q x

’ IIIX

J/21............................. Amf sqj JO J3JDBJBqO 3AIJBJU3S3jd3J

aqj pajiuiq qoiqAv puB ajnjBjs Aj pajinbaj asoqj uBqj

jaqjo 30IAJ3S Amf joj suoijBogipnb jo juaiuqsqqBjsa

aqj j(q pajBSojqB sbm Ajiunuuuoo aqj jo uotjoas-ssojo b

iuojj umbjp Amf jBijjBdiui ub oj jqSu s(juBpuajap aqx (? )

...................................................................3sbo juasajd sqj

ui XjjBjnoijjBd ‘puBd Amf aqj pajBpqBAui puB jadojd

-mi sbav ^juauiuiaAoS jo ujjoj UBOuaury aqj oj pasod

-do SAvaiA,, Are spjoq jojnf aAijoadsojd aqj jaqjaqAv

uoijsanb aqj Suiurejuoo ajieuuoijsanb aqj jo asn aqx (Z)

aovd

•IA

TA B LE OF A U T H O R IT IE S CITED

Cases. page

Adamson v. California, 332 U. S. 46................................................. 33

Alford v. United States, 282 U. S. 687.......................................... 106

Allgeyer v. Louisiana, 165 U. S. 578.................................................. 63

Arine v. United States, 10 F. 2d 778.................................................. 105

Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co., 259 U. S. 20, 66 L. Ed. 817....... 83

Ballenbach v. United States, 326 U. S. 613............98, 102, 105, 107

Bank of Columbia v. Okely, 4 Wheat. 233...................................... 64

Barnes, Matter of, 207 N. Y . 108..... ................................................. 74

Battelle, In re, 207 Cal. 227, 277 Pac. 725, 65 A. L. R. 1497.... 92

Bell v. State, 87 S. W . 1160, 48 Tex. Crim. App. 256.......... 93

Bi-Metallic Co. v. Colorado, 239 U. S. 441..................................... 69

Bihn v. United States, 328 U. S. 631................................................ 96

Blakeslee v. Carroll, 64 Conn. 223, 29 Atl. 473, 25 L. R. A. 106 76

Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624..... .........................147

Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616.......................................... 5 1 , 9 1

Bridge Co. v. United States, 105 U. S. 470..............................79, 83

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252.................................................. 35

Brown v. Dist. of Columbia, 127 U. S. 579..................... ........... ....114

Brown v. Walker, 161 U. S. 591........................................................ 60

Burdick v. United States, 236 U. S. 79.......... _................................ 52

Burnham v. Morrissey, 14 Gray (Mass.) 226............................ ....... 7 5

Carsten v. Pillsbury, 172 Cal. 572, 158 Pac. 218............................. 70

Catlette v. United States, 132 F. 2d 902.................................. ..66, 67

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227............................................... ....149

Chapman, In re, 166 U. S. 661............................................. .....118, 120

City of Chicago v. Tribune Co., 139 N. E. 86, 28 A. L. R.

1368 ......................... .................................................... ........................ 86

Coffin v. United States, 156 U. S. 433........................ .................. 29

vii.

Colonial Sugar Refining Co. v. Attorney General, A. T. 237.... 83

&

Vlll.

Ccmnselman v. Hitchock, 142 U. S. 547....................................... 56, 60

Crawford v. United States, 212 U. S. 193..... ................................. 135

Culp v. United States, 131 F. 2d 93..... .............................................. 66

Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. 277..................................... 39, 40, 52

Damon v. The Inhabitants of Granby, 2 Pick. (19 Mass.) 345....114

Daugherty’s case, 273 U. S. 175....................................................75, 90

District of Columbia v. Clawson, 300 U. S. 617................... 106

Dorsey v. Strand, 150 P. 2d 702, 21 Wash. 2d 217.....................114

Doyle, Matter of, 257 N. Y . 268-......................................................... 149

Edward’s case, 13 Rep. 9.................................................................31, 47

Entick v. Carrington, 19 How. St. Trials 1029............................... 50

Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261........................................................ 124

Fields case, 164 F. 2d 97, 82 U. S. App. D. C. 354........................ 99

Frazier v. United States, 92 L. Ed. (Adv. Op.) 758..................... 137

Gideon v. United States, 52 F. 2d 427......... 126

Gilchrist, Application of, 224 N. Y . Supp. 225................... ........... 74

Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S. 60........................... ,.128, 129, 130

Gouled v. United States, 255 U. S. 298....................................... 28, 48

Greenfield v. Russell, 292 111. 392.................. ................................76, 89

Grosjean v. American Trust Co., 297 U. S. 233............................. 79

Gunn, In re, 32 Pac. 470.................. ........ ........................................... 76

Hague, E x parte, 150 Atl. 322............................................................ 91

Harris v. United States, 331 U. S. 145............................................. 150

Harrison v. Evans, 1 English Reports, p. 1437............................... 34

Hill v. Wallace, 259 U. S. 44........................ ..................................... 67

Hirschfield v. Henley, 127 N. E. 252........................ ....................... 74

Humphries Executors v. United States, 295 U. S. 602................ 83

Hurd v. Hodge, 92 L. Ed. (Adv. Op.) 857..................................... 67

Jackson v. Jordan, 135 So. 138, 101 Fla. 616..... ............................. 128

Jones v. Securities and Exch. Com., 298 U. S. 1.......................... 28

PAGE

IX.

Kilbourn v. Thompson, 103 U. S. 182...................68, 71, 85, 89, 90

Kraus v. United States, 327 U. S. 614.... _....................................... 96

Lees v. United States, 150 U. S. 476................. .............................. 52

Local 309 U F W A (C IO ) v. Gates, Governor of Indiana, 75

Fed. Supp. 620............................................ ........................................ 46

Londoner v. Denver, 210 U. S. 373.................................................... 69

Lummus, J., Bowe v. Secretary of the Commonwealth, 320

Mass. 230 ............................................................................ ............... 44

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501..... ................................................ 67

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390............... .................................... 52

Millar v. Taylor, 4 Burr 2370...... 1.................................................... 47

Mooney v. Holahan, 294 U. S. 103.................. 64

Morgan v. United States, 298 U. S. 486......................................... 69

Morgan v. United States, 304 U. S. 1.............................................. 69

O ’Donoghue v. United States, 289 U. S. 516............................ 82, 84

Oliver, In re, 92 L. Ed. (Adv. Op.) 503............... ,.....................71, 76

Olmstead v. United States, 277 U. S. 438.................................28, 91

Patton v. United States, 281 U. S. 276........................................... 101

Penn-Ken. Gas & Oil Co. v. Warfield Natural Gas, 137 F. 2d

871; cert. den. 320 U. S. 800............... .............................................116

Pennsylvania Co. v. Cole, 132 Fed. 668....................................... .....114

People v. Barnes, 204 N. Y. 125........................................................ 91

People v. Cleveland, 271 111. 226, 110 N. E. 843............................ 115

People v. Keeler, 99 N. Y. 482................................................... 74, 90

People v. Lovercamp, 165 111. App. 532........................................... 93

People v. Nathan, 139 Misc. 345, 249 N. Y. Supp. 395..............137

People v. Webb, 5 N. Y. Supp. 855, 23 N. Y. St. Rep. 324........

......................... ................................ -.....................— -...........73, 74, 91

Picking v. Pennsylvania Ry. Co., 151 F. 2d 240............................. 66

PAGE

X.

Powe v. United States, 109 F. 2d 147; cert. den. 309 U. S.

679 ....................................... ................................ ............................67, 79

Prentiss v. Atlantic Coast Lines, 211 U. S. 210............................. 88

Pullman Co. v. Vanderhoeven, 107 S. W . 147, 48 Tex. Civ.

App. 414 .............................................................................................. 94

Quarles, In re, 158 U. S. 532, 39 L. Ed. 1080......................... ....... 80

Quercia v. United States, 289 U. S. 469.................................101, 102

Respublica v. Gill, 3 Yeates 429, 161 U. S. 633............................ 39

Reynolds v. State, 199 Miss. 409, 24 So. 2d 781.............................128

Rogers v. State, 75 So. 997, 16 Ala. App. 58................................... 94

Ross v. Railway Commission of California, 271 U. S. 583, 70

L. Ed. 1101........................................................ .................. .............. 67

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91, 89 L. Ed. 1495, 162

A. L. R. 1330.................... ................ ............................................66, 67

Shelley v. Kramer, 92 L. Ed. (Adv. Op.) 845............................. 67

Shepard v. United States, 290 U. S. 96........................................... 96

Sinclair v. United States, 279 U. S. 263...............................75, 90, 92

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128........................ ........................ ....128, 129

Spier v. Baker, 120 Cal. 370................ ................................ , ............... 84

St. Mary’s Church, 7 Serg. & Rawle (28 Pa.) 517....................114

State v. Dilworth, 80 Mont. I l l ........................................................116

State v. District Court, 86 Mont. 509, 284 Pac. 266....................127

State v. Guilbert, 78 N. E. 931...................... ...................................... 76

State v. Radon, 45 W yo. 383, 19 P. 2d 177....................................127

State ex rel. Johnson v. St. Louis etc. Ry., 286 S. W . 360,

315 Mo. 430..........................................................................................116

State ex rel. School District of Afton v. Smith, 336 Mo. 703,

80 S. W . 2d 858................................................................................... 115

Steele v. Louisville & National Ry. Co. & Brotherhood of Loco

motive Firemen, 323 U. S. 192................................................. 81, 82

Stewart Machine Co. v. Davin, 201 U. S. 548................................ 67

PAGE

Stockton v. Leddy, 55 Colo. 24................................................... ......... 76

Sullivan v. State, 161 N. E. 265, 200 Ind. 43........ ........................ 93

Summers, In re, 325 U. S. 561............................ .............................. . 35

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U. S. 217............... 124, 128, 130

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516........................................... 44, 50, 86

Tot v. United States, 319 U. S. 463.................................................. 70

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312...................................................... 67

Trumbo v. United States, No. 9873.................................................... 90

United States v. Bell, 81 Fed. Rep. 830'....................... .............53, 61

United States v. Butler, 297 U. S. 1..................... ............. ............ 67

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299............................. ,......66, 80

United States v. Constantine, 296 U. S. 287.......................... 67

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542............... 79

United States v. Hautau, 43 Fed. Supp. 507..................... ...... . 94

United States v. Kirschenblatt, 16 F. 2d 202, 51 A . L. R, 416.... 27

United .States v. Lovett, 328 U. S. 303..................... .........27, 63, 70

United States v. Murdock, 290 U. S. 389...............................99, 101

United States v. Owlett, 15 Fed. Supp. 736.............................83, 87

United States v. Paramount Pictures, 92 L. Ed. (Adv. Sheets)

903 ............. .......,.................................................. ........ .............. ........ ;. 76

United States v. Shapiro, No. 49, Oct. Term, 1947, decided

June 21, 1948........................................................................................ 56

United States v. Stone, 188 Fed. 836....................... 66

United States v. Trierweiler, 52 Fed. Supp. 4........................ 66

United States v. Waddell, 112 U. S. 80................. 67

United States v,. Woods, 299 U. S. 123..... ........ ...............................

..................................................... ....133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 143

Wagner v. Supreme Lodge, 87 N. W . 903, 128 Mich. 660....... 94

Wells, etc. Counsel v. Littleton, 60 Atl. 22, 100 Md. 416.......... 94

West Virginia v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 6 2 4 . . ...................28, 40,. 52

Yarbrough, Ex parte, 110 U. S. 651, 28 L. Ed. 274.................... 80

Yick AYo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356................................................. 79

x i .

PAGE

H oly B ible page

Deuteronomy 17:4, 24:10................. .................................... 29

Joshua 7:10-26 ......................................... 29

Matthew 26:63 ........................................................................................ 29

M iscellaneous

Bowers, Jefferson and Hamilton, p. 378........................................ . 49

Chaffee, Free Speech in the United States, pp. 234, 350-1,

550-63 .................................................................................................. 81

Chaffee, Free Speech in the United States, pp. 360-361................ 80

Clark, Speaker, May 18, 1918, p. 6689.............................................. 112

de Tocqueville Alexis, Democracy in America (N . Y .) , Vol.

I, p. 196.................................................................................................. 44

Ebeling, Congressional Investigations (N . Y., 1928), p. 339..... 60

Gillett, Speaker, June 17, 1922, p. 8928..........................................112

Horne, Mirrour of Justices (Washington, 1903), Sec. 108, p.

245, Subsec. 10, p. 246....................................................................... 30

Ickes, Harold L., syndicated column for June, 1947...................... 132

x i i .

Johns Hopkins Studies in Historical and Political Science, Se

ries 55, No. 2 (Lasson, The History and Development of the

Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, 1937,

pp. 13, 43-46).... .............. ..................................................... .........28, 37

Lea, A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages, I, p. 407.. 31

McCreary, The Developments of Congressional Investigative

Power (N . Y., 1940), pp. 80, 81.................................................. 68

1 Montesquieu, Spirit of Laves (Cincinnati, 1873), p. 10........ 85

Mott, Due Process of Law (1926), p. 9, notes 31, 33; p. 12,

note 37; pp. 86, 108, 115-16, 126, 132-3, 135, 142, 159-60..... 64

38 New Republic (M ay 21, 1924), pp. 329, 331, Frankfurter,

Hands Off the Investigations...................................................... 68

New York Times, March 20, 1948................................. ........ .............147

Patterson, Free Speech and a Free Press, pp. 6-7....... ............80, 81

Patterson, Free Speech and a Free Press, pp. 14, 228..... ............ 81

x i n

Patterson, Free Speech and a Free Press, p. 134............................ 81

President Thomas Jefferson’s letter to Benjamin Rush, April

21, 1803 ............................................ ................................................... ISO

Radin, Roman Law (St. Paul, 1927), pp. 475-476........................ 29

Random House (1948), Andrews, Washington Witch-Hunt........137

Report of the Joint Committee on the Organization of Con

gress— pursuant to House Cong. Res. 18— Rep. No. 1011,

Sec. I, subd. 6......................................................................................113

Woodley, Thaddeus Stevens, pp. 29, 38........................................ ..... 41

Wyler, Radio broadcast, October 26, 1947.................... ............... .....148

Statutes ..

Act of January 24, 1862, Chap. 11, 12 Stats. 833................ ......... 59

Act of June 22, 1938, Chap. 594, 54 Stats. 942........................ 59, 119

Act of Congress, 49 Stats, at L. 682.........:........................... ............ 134

District of Columbia Code, 1940 Ed., Sec. 11-306....................... 1

District of Columbia Code, 1940 Ed., Sec. 17-1.01........ 1

District of Columbia Code, Title 11, Sec. 1417......................120, 127

Federal Rules o f Criminal Procedure, Rule 2 1 (a )................131, 137

House Rules and Manual, 80th Congress, Sec. 407........................ 112

House Rules and Manual, 80th Congress, Sec. 409.................... 112

House Rules and Manual, 80th Congress, Sec. 943........................ 110

Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, Sec. 133 (b )_____ 110, 115

Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, Sec. 202c......................... 113

Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, Sec. 202 (d )........ 115

Magna Carta, Sec. 39, Provisions in the Body of Liberties of

1641, Massachusetts Bay Colony................................................... 64

Public Law 601..... ............................................................................ .. 2

PAGE

XIV

Revised Statutes, Sec. 102, Act of June 22, 1938, Chap. 594, 52

Stat. 942, U. S. C„ Title 2. Par. 192.......................................... . 1

Revised Statutes, Sec. 104.................................................................. ...119

Revised Statutes, Sec. 859..... ............ .............................. ....... ............ 59

Revised Statutes, Sec. 5508................................................................... 66

Revised Statutes, Sec. 5510................................................................... 66

United States Code, Title 2, Sec. 192....... 96

United States Code, Title 2, Sec. 194............................... 119

United States Code, Title 18, Sec. 51.................. 66

United States Code, Title 18, Sec. 52............. 66

United States Code, Title 28, Sec. 24........................................ 144

United States Code, Title 28, Sec. 25...... 144

United States Code, Title 28, Sec. 634................................. .. 59

United States Code Annotated, Title 28, Sec. 391........................ 98

United States Constitution, Art. I, Sec. 6, clause 1......................... 85

United States Constitution, Art. I, Sec. 10... 40

United States Constitution, First Amendment............20, 23, 24, 77

United States Constitution, Fourth Amendment.............................

............................................................................... 20, 21, 23, 50, 51, 55

United States Constitution, Fifth Amendment.... .......................

..................................... ...20, 21, 23, 37, 39, 40, 50, 51, 54, 55, 78, 87

United States Constitution, Ninth Amendment.........20, 22, 78, 87

United States Constitution, Tenth Amendment.........20, 22, 78, 87

United States Criminal Code, Sec. 19................................................. 66

United States Criminal Code, Sec. 20............. 66

T extbooks and P eriodicals.

American Annotated Cases, 1916B, p. 1055.................... ................ 76

Author’s League Bulletin, March, 1948......................... ................... 148

Congressional Globe (29th Cong., 1st Sess.), 1845-1846, App.

p. 455 .................................................................................................. 43

Congressional Globe (34th Cong., 3d Sess.), pp. 404, 405-6, 432 57

PAGE

XV.

Congressional Globe (34th Cong., 3d Sess.), p. 427...................... 58

Congressional Globe (37th Cong., 2d Sess.), p. 431..... 58

Congressional Record (44th Cong., 1st Sess.), p. 1564................ 59

Congressional Record, Nov. 24, 1947, p. 10879............................... 91

Cooley, Constitutional Limitations, pp. 1375-7................................. 86

22 Corpus Juris, p. 982, note 89..................................................... ..116

70 Corpus Juris, p. 738................ ............ ............ ............................. 52

10 Debates, 23d Cong., 1st Sess., Pt. 4, App., p. 194................ 40

13 Debates, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., App., pp. 199, 200, 202........ 54

34 Edward III, Chap. 1....................................................................... 31

3 Elliott’s Debates, pp. 445-449...................................................... 39

Elsynge’s Method of Passing Bills, p. 11........................................... 112

5 Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, p. 114.................................... 60

6 Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences, p. 449, Laski, Freedom

of Association ..................................................... 45

Gettysburg Compiler, May 7, 1839...................................................... 41

3 Greenleaf’s Evidence (16th Ed., Boston, 1899), p. 35,

note 4 .......................................... 29

4 Harvard Law Review, p. 193, Warren and Brandeis, The

Right to Privacy............................................................................. 47

172 Harper’s Magazine, p. 171, Friedrich, Professor of Govern

ment, Harvard (1936)............ 35

Harper’s Magazine (Sept., 1947), article by Prof. Commager.—146

15 Harvard Law Review, p. 615 (W igm ore)...................... ........ 30

3 Hines, Precedent, Sec. 1754..........................................................113

3 Hines, Precedent, Sec. 1757..........................................................113

3 Hines, Precedent, Sec. 1758......... 113

4 Hines, Precedent, Sec. 4577......................................................... 113

4 Hines, Precedent, p. 4586........................ 112

3 How. State Trials, p. 1315.................... 32

PAGE

XVI.

Lawyers’ Reports Annotated, 1917F..... ............................................. 76

Lawyers Reports Annotated, 1917F, p. 294....................................... 90

28 Ruling Case Law, p. 425, 75 Am. St. Rep. 322...................... 52

8 Wigmore on Evidence, 3rd Ed., p. 161..................................... 55

21 Virginia Law Review, p. 763 (Pittman)................................... 33

34 West Virginia Law Quarterly, No. 1, p. 2, W ood, The

Scope of the Constitutional Immunity..................................... 36

34 West Virginia Law Quarterly, No. 1, pp. 13-14, W ood, The

Scope o f the Constitutional Immunity.................. ............ ......... 51

25 W ho’s Who, 1948, p. 1436............................................................ 1

PAGE

IN D E X TO A P P E N D IX A.

PAGE

Statutes involved ............................................................. 1

Act of Congress of August 22, 1935, Chap. 605, 49 Stats, at

Large 682 ................................................................................. 2

District of Columbia Code, Title X I, Sec. 1417..... ..................... 2

Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, Sec. 121(b), Public

Law 601, Chap. 753, 79 Cong., 2d Sess., 60 Stats. 828,

amends Rule X I (1 ) (2 ) o f Rules of the House of Repre

sentatives .................. 1

Revised Statutes, par. 102, as amended by Chap. 594, Act of

June 22, 1938, 52 Stats, 942; U. S. C. A., Title 2, par. 192 1

In the United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia

No. 9872

J o h n H o w a r d L a w s o n , Appellant,

v.

U n i t e d S t a t e s o f A m e r i c a , Appellee.

Appeal from the District Court of the United States for the

District of Columbia.

OPENING BRIEF FOR APPELLANT.

Jurisdictional Statement.

This is an appeal from a judgment of the District Court

o f the United States for the District o f Columbia, con

victing John Howard Lawson of violating Rev. Stat. Sec.

102, as amended by C. 594, Act o f June 22, 1938, C. 594,

52 Stat. 942, U. S. C. Title 2, Par. 192.

Jurisdiction below was based on Section 11-306, D. C.

Code, 1940 Ed. Jurisdiction of this Court is conferred

by Section 17-101 D. C. Code, 1940 Ed.

Statement of the Case.

John Howard Lawson, a dramatist and screen writer

(Vol. 25 W ho’s Who, 1948, p. 1436) was convicted of

contempt o f Congress. The sentence imposed the maxi

mum penalty, imprisonment for a year and a fine of

$ 1,000.00.

The defendant challenged the indictment by motion to

dismiss on the ground, among others, that it did not state

an offense. (J. A. 11.) The motion was denied! (J. A .

6.) A motion to transfer the cause to another district for

trial was also denied. (J. A. 6.) The defendant entered

a plea of “ not guilty.”

On April 12, 1948, as the case was called for trial, the

defendant moved the trial justice, the Honorable Edward

M. Curran, to disqualify himself for bias and prejudice.

This motion was denied. (J. A. 56.) Another motion was

made to transfer the cause to another district for trial,

based on events which had occurred since the former mo

tion, coupled with earlier events; this motion was likewise

denied. (J. A. 57.)

The defendant then filed a Challenge and Motion to

Dismiss the jury panel on the ground that the panel had

not been selected in a manner designed to obtain a repre

sentative jury and on the further ground that, in view of

the nature of the case, the preponderance of government

employees on the panel prejudiced the defendant with re

spect to his right to an impartial jury. The Court took

evidence on the motion and denied it.

Thereupon a jury was impaneled. When the defendant

had exhausted his preemptory challenges he asked the

Court for additional challenges, but this request was de

nied. (J. A. 166.) Because the indictment was for con

tempt of Congress and concerned an alleged interference

with the orderly processes of government, the defendant

challenged for cause each government employee and each

near relative o f a government employee. These challenges

were denied. (J. A. 166.)

When the jury had been selected the cause proceeded to

trial. The evidence received established the following

facts.

The first session of the 79th Congress (in 1945) amend

ed Public Law 601 and made the House Commitee on Un-

American Activities a permanent committee. (J. A. 174,

Govt. Ex. 2.)

Between October 20 and October 30, 1947, members of

the House Committee, purporting to act as a sub-commit

tee, held hearings, in Washington, D. C., on the subject,

as designated by them, “ Communist Infiltration of the

Motion Picture Industry.” The defendant was not a

-3—

voluntary witness but appeared in response to subpoena

served upon him at his residence in California. He testi

fied on October 27, 1947. The Committee had never at

any time seen any o f the motion pictures written by the

defendant. (J. A. 236-7.)

During the course o f the chairman’s opening statement

on October 20, 1947, he said:

“ The question before this committee, therefore, and

the scope o f its present inquiry, will be to determine

the extent of communist infiltration in the Hollywood

motion picture industry. W e want to know what

strategic places in the industry have been captured

by these elements, whose loyalty is pledged in word

and deed to the interests o f a foreign power.” (See

p. 3 o f the printed transcript of the Committee Hearings.)

Twenty-four witnesses preceded the defendant. (J. A.

200.) Some of the witnesses attacked his character, in

tegrity, and reputation, and the prosecution relied upon

this testimony in its efforts to establish the pertinence of

questions addressed to the defendant. (J. A. 223-228,

230, 232.)

On the morning o f October 27, 1947, three members o f

the Committee were present. The Chairman opened the

hearing on that day by saying: “ The record will show

that a sub-committee is present consisting of Mr. Vail,

Mr. McDowell, and Mr. Thomas.” Over defendant’s

objections, the Chairman of the Committee was allowed

to testify that as a matter o f law he had the authority to

appoint a sub-committee, and that he appointed a sub

committee at the outset o f the hearings by making the

statement set forth above. (J. A. 183-6, 197-8.)

At the outset of the defendant’s testimony before the

Committee, he asked leave to read a statement. The Chair

man said, “ The statement will not be read. I read the

first line.” (J. A. 188.)

The defendant protested this refusal and called attention

to the fact that executives of motion picture producing

4

companies, Mr. Jack Warner and Mr. Louis B. Mayer,

had been accorded the privilege of reading their state

ments. Nevertheless, the defendant was not permitted to

read his statement.

After the defendant had answered preliminary, identi

fying questions, the Committee asked whether he was a

member of the Screen Writers’ Guild. The defendant

stated, first, that he protested the question, that the Com

mittee had no power to ask it. He was interrupted numer

ous times in the course of his reply before he was able to

say that it was a matter of public record that he was a

member of the Guild. The Committee interrogated him

concerning his activities as a member and officer o f the

Screen Writers’ Guild. The defendant answered these

questions, protesting them, asserting they violated his

constitutional rights, and stating that the information

sought was a matter of public record, and that he was a

former President o f the Guild. Similar questions con

cerning his screen writing were answered in the same way,

by protests, by the assertion that the questions invaded his

right, and by the statement that his authorship of motion

pictures was a matter of public record.

The defendant was then asked: “ Are you now or have

you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” Again

the defendant replied by protesting, by saying that the

question violated his rights and exceeded the powers of

the Committee. He asked that witnesses who had testified

concerning him be recalled for cross-examination so that

he could show they had perjured themselves. Members of

the Committee and its counsel, Mr. Stripling, repeatedly

interrupted the defendant’s reply. The testimony was

brought to a close by the Chairman in the following man

ner :

“ The Chairman (pounding gavel). W e are going

to get the answer to that question if we have to stay

here for a week.

“ Are you a member o f the Communist Party, or

ha've you ever been a member o f the Communist

Party?

“ Mr. Lawson. It is unfortunate and tragic that I

have to teach this committee the basic principles of

American—

“ The Chairman (pounding gavel). That is not

the question. That is not the question. The question

is : Have you ever been a member of the Communist

Party ?

“ Mr. Lawson. I am framing my answer in the

only way in which any American citizen can frame

his answer to a question which absolutely invades

his rights.

“ The Chairman. Then you refuse to answer that

question; is that correct?

“ Mr. Lawson. I have told you that I will offer my

beliefs, affiliations, and everything else to the Ameri

can public, and they will know where I stand.

“ The Chairman (pounding gavel). Excuse the wit

ness—

“ Mr. Lawson. As they do from what I have writ

ten.

“ The Chairman (pounding gavel). Stand away

from the stand—

“ Mr. Lawson. I have written Americanism for

many years, which you are trying to destroy.

“ The Chairman. Officers, take this man away

from the stand-—” (J. A. 196-7.)

To meet the prosecution’s evidence concerning the per

tinence of the question which was the subject o f the in

dictment and concerning the status o f the Congressmen

who acted as a sub-committee, the defendant served sub

poenas duces tecum on the Committee’s chief investigator

and on the Clerk of the House. These subpoenas called

for specified records of the Committee; one covered the

period from May 26, 1938, to August 2, 1946, to the time

of the trial; they called for the production o f the Com

mittee’s records relating, among other things, to the Com

mittee’s investigation of the defendant, to the Commit

tee’s interpretation and application of the terms “ subversive

and Un-American propaganda.”

On the Government’s motion to quash the subpoenas,

the defense stated it expected to elicit by means of the

records which were the subject o f the subjoena the follow

ing: The Committee was authorized to conduct the in

vestigation only by full Committee; the hearings were not

held for any legislative purpose but were in fact held for

the purpose of seeking to control the subject and content

of motion pictures and to compel the discharge and black

listing o f named persons, including the defendant; that

before the hearing was commenced the Committee believed

it had all o f the information which could have been ob

tained by the hearing. On request o f the defendant the

Court considered separately each item called for by the

subpoenas and further acted on the motion to quash on the

basis that if the period o f time covered by any item was

deemed unreasonable the subpoenas would be amended to

cover a shorter period of time. The subpoenas in their

entirety were quashed. (J. A. 318-28.)

Thereafter, during the course of the trial, additional

subpoenas duces tecum were served on the Committee’s

chief investigator and on the Clerk of the House; these

subpoenas called for designated documents relating to the

period from January 1 to October 27, 1947, and referring

solely to the subject matter of the hearing, the investiga

tion o f the defendant, and the existence of the sub-com

mittee. On the Government’s motion to quash these sub

poenas, the defense told the Court that they expected to

establish the facts stated above. The Court quashed these

subpoenas. (J. A. 343-6.)

After the close of the evidence the Court told the jury:

“ There is nothing in the record to indicate that he (the

defendant) was trying to answer the question,” and that

the reasons given by the defendant in asserting his posi

tion were not in the case. (J. A. 349.)

During the course of the trial, the Court on motion of

the government cut off many lines of inquiries begun by

the defense. (J. A. 199, 202-8.) Accordingly, the de

fense, by means o f exhibits, given numbers for identifica

tion, made a number of offers o f proof. For the conven

ience of the Court, they are here summarized. They in

clude offers to prove that the primary purposes of the

hearing were to procure the discharge of the defendant,

to blacklist him from employment and to censor the motion

picture screen. The testimony offered to substantiate this

offer o f proof included the declarations, acts and conduct

o f each of the Congressmen who purported to sit as a sub

committee on October 27, 1947. The proffered evidence

included, among other things:

(1 ) A sub-committee of the House Committee on

Un-American Activities, with its chief investigator,

Stripling, went to Los Angeles in the Spring of 1947

and there examined a number of motion picture pro

ducers, including Jack Warner, and called upon them

to discharge and to suspend certain writers and di

rectors whom the Committee considered to be Com

munists, among whom was the defendant, Lawson.

The effect o f these hearings was recognized by a wit

ness called by the Committee, who said he could not

answer a question as to whether Communism was in

creasing or decreasing in Hollywood, because ‘Tt is

very difficult to say right now, within these last few

months, because it has become unpopular and a little

risky to say too much. You notice the difference.

People who were quite eager to express their thoughts

before begin to clam up more than they used to.”

The effect o f the Committee’s action was also pointed

out by Mr. Johnston, the head o f the Motion Picture

Producers’ Association, who stated that while Sena

tor Robert Taft need not worry about being called

a Communist, not every American was in that posi

tion. Charges o f this kind can take away everything

that a man has— “ his livelihood, his reputation, and

his personal dignity.” [Ex. 10 for ident.] (J. A.

542.)

(2 ) The producers at first rejected the demand of

the sub-committee that certain writers be discharged

and blacklisted and said that such conduct was un

lawful. (J. A . 545.)

(3 ) In the Summer of 1947 the Committee sent

two o f its investigators, Leckie and Smith, to Holly

wood, there to call upon the producers, including Louis

B. Mayer, executive in charge o f production at Metro-

Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, and Dore Schary, executive

m charge of production at RKO Radio Pictures.

These investigators urged the producers “ to clean out

their houses else there would be trouble in the industry

from the House Committee.”

(4 ) The Committee had since its inception main

tained records and files which now contain over a mil

lion names of persons and one thousand names of

associations deemed by the Committee to be un-

American, subversive or Communistic; these records

are growing; the files are made available to Federal

and State and other government agencies; names for

the records are obtained from various sources, includ

ing persons designated as subversive by individuals

whom the Committee deemed reliable; one of the

purposes o f the Hollywood hearings was to obtain

new names for this growing file. (J. A. 327-8.)

(5 ) During the hearings a member o f the Commit

tee urged the Motion Picture Producers Association

“ T o concern itself with cleaning house in its own in

dustry . . . I don’t think you can improve the

industry to any greater degree and in any better

direction than through the elimination of the writers

and the actors to whom definite Communistic leanings

can be traced.” The Committee’s counsel joined in the

demand that “ Communistic influences . . . and I

say Communist influences; I am not saying Com

munists” ; be eliminated from the industry by cutting

“ these people off the payroll.” (J. A. 517.)

(6 ) One o f the members of the Committee stated

the function of the Committee in this way: “ .

o f course, we have the problem of eliminating the

Communist element from not only the Hollywood

scene but also other scenes in America, and we have

to have the full support and cooperation of the execu

tives for each of those divisions.” (J. A. 518.) At

another point, the Chairman of the Committee stated

that four o f the unfriendly witnesses before the Com

mittee have been shown to have “ extensive Communist

and Communist-front records. Yet, this kind of

people are writing scripts in the moving* picture in

dustry.” (J. A. 521.) He then went on to state

that that is one of the reasons for the investigation,

and that the investigation will be beneficial to the

American people and to the industry “ because you are

the people . . . you persons high up in the industry

can do more to clean your own house than can any

body else, but you must have the will power, and we

hope that by spotlighting these Communists you will

acquire that will.” (J. A. 522.)

(7 ) The Chairman closed the hearings on October

30, 1947, with the following public appeal to the

producers:

“ The Chairman. * * * I want to emphasize

that the committee is not adjourning sine die, but will

resume hearings as soon as possible. The committee

hearings for the past two weeks have clearly shown

the need for this investigation. Ten prominent figures

in Hollywood whom the committee had evidence were

members o f the Communist Party were brought be

fore us and refused to deny that they were Com

munists. It is not necessary for the Chair to em

phasize the harm which the motion picture industry

suffers from the presence within its ranks o f known

Communists who do not have the best interests o f the

United States at heart. The industry should set about

immediately to clean its own house and not wait for

public opinion to force it to do so.” [Ex. 10 for

ident, J. A. 526.] (J. A. 257-60.)

(8 ) One of the purposes of the hearing was to

stop the production of pictures which depicted the

Negroes in a favorable light, and one of the reasons

why the defendant Lawson was called by the Com

— 9—

10—

mittee was because he wrote pictures which did this;

further, the purpose o f the hearing- was to control the

content of motion pictures in accordance with the

ideas of the Committee, and the function o f the Com

mittee in the Hollywood hearings was that of “ a

grand jury carrying on an' investigation.” (J A.

325-6.)

(9 ) One o f the purposes of the hearing and of

the questions put to the defendant was to compel the

motion picture industry to make only the kind of

pictures the Committee believes should be seen by the

American public. The Chairman asked one witness

whether he believed that these public hearings would

“ aid the industry in giving it the will to make these

pictures.” The Commitee attacked pictures the con

text o f which it disapproved. One of these was

“ Mission to Moscow,” written by former Ambassador

Davies. [Ex. 10 for ident.j (J. A. 489-90.)

(10) The Committee called on the motion picture

industry to eliminate from pictures anything which

the Committee considered Communistic or un-Amer

ican or subversive propaganda. The Committee chair

man and other Congressmen, members of the Com

mittee, recognizing that “ it would be very foolish for

a Communist or a Communist sympathizer to attempt

to write a script advocating the overthrow of the

government by force or violence,” found un-American

propaganda in “ innuendos and double meanings, and

things like that” (J. A. 504), in “ slanted lines”

(J. A. 505), in “ subversion” inserted in the motion

pictures “ under the proper circumstances, by a look,

lay an inflection, by a chang-e in the voice.” (J. A.

505.) Among the subversive manifestations in mo

tion pictures specified by the Committee were refer

ence to some crooked members o f Congress, to dis

honest bankers or senators, to a minister shown as

the tool o f his richest parishioner, and to presenta-

ion o f bankers as unsympathetic men. (J. A. 506-10.)

(11) In November, 1947, following the close o f the

Washington hearing, the industry complied with the

Committee’s demand for a blacklist affecting the

—11

defendant and others named by the Committee.

Unexpired contracts of other so-called 'unfriendly”

witnesses were abruptly terminated and further em

ployment in any branch of the industry was denied to

them. (J. A. 263 and 167 F. 2d 241, 254, note 8.)

(12) Thereafter, the Committee in its request for

contempt citations claimed “ the credit for these dis

charges and this blacklist.” [See Transcript, J. A.

263-4]; Congressional Record, Monday, November

24, 1947, at page 10890 et seq.:

“ Congressman Mundt: . . . Then to go on, I

want to congratulate the Fox Moving Picture Co.,

the Twentieth Century-Fox, I believe it is called,

which passed a resolution the other day, and I want

to read it to you. ‘Resolved, that the officers o f this

corporation be and they are hereby directed, to the

extent that the same is lawful, to dispense with the

services of any employee who is an acknowledged

Communist or of any employee who refuses to answer

a question with respect thereto by any committee of

the Congress o f the United States and is cited for

contempt by reason thereof.’

“ I congratulate Twentieth Century-Fox on that

progressive and patriotic step. I think it is time, and

I think it is just a little late, that Hollywood take

that action but I congratulate it now because it is

highly important that Communists be purged out of

the moving picture industry. This desirable objective

has been materially aided by the recent hearings in

Washington as the general public is becoming rapidly

alert to the problem.”

On various occasions the Committee has considered the

meaning of the phrase, “ un-American activities” and the

phrase “ un-American propaganda,” but it has never ex

pressly adopted any definition or standard for said phrases.

(J. A. 254-6.)

The defendant maintained that the statute and resolu

tions establishing the committee were not free from am

biguity; that, therefore, it was proper and necessary to

consider the manner in which said statute and resolutions

1 2

had been interpreted and applied by the Committee;

that only from such construction and interpretation was

it possible to determine whether the existence of the Com

mittee offended the Constitution, whether it had acted in

excess o f its powers and whether the question asked was

pertinent.

Accordingly the defendant offered to prove the Com

mittee’s interpretation and application of the critical lan

guage of the statute; and further offered to prove that in

asking the question which was the subject of the indict

ment the Committee had acted in accordance with the

meaning attributed to those words by the Committee.

The defendant therefore submitted a detailed offer o f

proof relating to the Committee’s past activities prior to

October 20, 1947 [marked Deft. Ex. 9 for ident., j . A.

420]. The Court excluded this offer in its entirety.

(J. A. 249-53.) By this offer, the defendant sought to

prove that:

(a ) During its entire existence the Committee has

considered its authority under Public Law 601 and

preceding resolutions, identical in language, to be

sufficiently broad in scope to permit investigation and

examination, including the summoning of witnesses

and subpoenaing of records, of every kind of organi

zation, whether fraternal, social, political, economic,

or otherwise, and of every kind of propaganda includ

ing unrestricted inquiry into any and all ideas,

opinions and beliefs held or promulgated and the

association of any individuals.

(b ) Although the Committee has never been able

to agree upon a specific definition of the terms, “ un-

American propaganda that . . . attack the prin

ciple o f the form of government as guaranteed by our

Constitution,” it has conducted its hearings, drawn its

finds and conclusions, determined the pertinency of

questions and inquiry, summoned witnesses and con

ducted investigations, upon the assumption and basis

that the said terms included the following ideas and

beliefs:

— 1 3

1. Political opinions generally called “ new deal” be

cause of their advocacy by the late President

Roosevelt. On one occasion Chairman Thomas

speaking for the entire Committee, said that the

propaganda being disseminated by agencies o f

our national government is “ just as un-American

as the propaganda that is being spread by those

so-called un-American groups.” [Ex. 9 for

ident.] (J. A. 427.) Numerous other examples

appear in the exhibit (pp. 3-7, inch). (J. A.

422-7.)

2. The opinion that the Committee on un-American

Activities is undesirable. [Ex. 9 for ident.]

(J. A. 427-31.)

3. The opinion that incumbent members of Congress

should be defeated and others elected in their

place. [Ex. 9 for ident.] (J. A. 431.) The

Committee in one of its reports states that “ the

essence of totalitarianism is the destruction of the

parliamentary or legislative branch o f govern

ment” and that through “ criticizing individual

members o f Congress” there exists a “ widespread

movement to discredit the legislative branch of

our government.” [Ex. 9 for ident., J. A. 433.]

Time magazine was declared to have been en

gaged in un-American activities because it “ gives

a two-page spread to the attack made upon

Congress by the Union for Democratic Action.”

[Ex. 9 for ident., J. A. 434, 444.]

4. The following ideas and beliefs concerning eco

nomics :

(a ) To be in favor of a planned economy ;

(b ) To oppose monopoly;

(c ) To attack “ the Standard Oil Company of

New Jersey and other responsible industrial

organizations” ;

(d ) T o “ viciously attack cartels” ;

(e ) To say that landlords have highpowered

lawyers while tenants do not;

— 14—-

( f ) T o attack private ownership;

(g ) T o believe in the abolition o f inheritance;

(h ) Skepticism as to advertising;

( i ) To defend sit-down strikes. [Ex. 9 for

ident, J. A . 438-41.]

5. The following political opinions:

(a ) Opposition to the present system of checks

and balances in the Constitution;

(b ) Opposition to the method o f choosing mem

bers of the legislature in New Jersey;

(c ) Advocacy of the formation of a national

farmer labor party;

(d ) Advocacy o f the Geyer anti-poll tax bill.

[Ex. 9 for ident., J. A. 453.]

6. The following opinions on foreign policy:

(a ) Advocacy of withdrawal of American troops

from China;

(b ) Belief in the desirability of the dissolution

o f the British Empire;

(c ) Calling for civilian use of atomic energy

and criticising- its military use;

(d ) Advocacy of the plan advanced by former

Secretary o f the Treasury Henry Morgen -

thau, Jr., with respect to our policy in

Germany;

(e) The belief that the cause of the Spanish

Loyalist Government was just and that the

government o f Franco Spain is not demo

cratic. (J. A. 454.)

7. Opposition to universal military training. [Ex.

9 for ident., J. A. 461.]

8. The following ideas and beliefs with respect to

our society:

(a ) Absolute racial and social equality;

(b ) Opposition to a belief in the divine origin

o f the rights of man;

1 5

(c ) Unity regardless of race, creed, and color

for a common goal o f peace and prosperity.

[Ex. 9 for ident, J. A. 461.]

9. Ideas and beliefs favorable to the defense of

civil liberties:

(a ) Acting as counsel for the Communist Party

in civil liberty cases;

(b ) Protesting the denial of a meeting place

for a speech by Henry A. Wallace;

(c ) Protesting the denial o f the right o f Paul

Robeson to speak in Albany and Peoria;

(d ) Signing an open letter for Harry Bridges;

(e ) Supporting the Scottsboro, and Sacco and

Vanzetti cases;

( f ) Joining in a resolution signed by such per

sons as President Woolley of Mount Hol

yoke, Professor Chafee of Harvard, Pro

fessor Fairchild of New York University,

Bishop McConnell of the Methodist Church,

and Dean Fleming James of the Divinity

School o f the University of the South, which

opposed outlawing the Communist Party.

[Ex. 9 for ident., J. A. 461-6.]

10. The promulgation o f any and all ideas whatso

ever in books or newspapers or by radio are

considered by the Committee as within its scope;

it has condemned books and newspapers with

which it disagreed, and it has threatened radio

networks with legislation establishing censor

ship because of utilization by such networks of

radio commentators who expressed verboten

ideas. [Ex. 9 for ident., J. A. 441-53.]

11. Out of 207 names sent by the Committee to the

Department of Justice as subversive, 7 were in

cluded solely because their names were carried

in the files o f the “ Washington Committee for

Aid to China,” 42 solely because they were

listed as members of the “ Washington Book

Shop,” 33 solely because they were at one time

1 6 -

members of the “ League for Peace and Democ

racy,” and 73 for the sole reason that their names

were on a list o f the “ Washington Committee

for Democratic Action.” [Ex. 9 for ident., J. A.

474-5.]

12. The Committee has proceeded upon the theory

that an idea approved by Communists is, ipso

facto, Communistic and un-American. Anyone

who supports such an idea is either a Com

munist or a supporter. Thus, the head of the

Communistic Party urged labor political action

in the 1944 election. The fact that such action

was afterward taken by labor unions was proof

that the unions were Communistic and un-Amer

ican. One of the Committee’s methods has been

to proclaim guilt by association; it designates

as a Communist organization any organization

to which Communists belong; then it designates

as Communists all persons who belong to that

organization, regardless of the purposes of the

organization. Thus, in its 1944 P. A. C. report,

Julius Emspak, key official o f United Electrical,

Radio and Machine Workers of America is con

demned as un-American because of statements

made by one James Carey, a former official of

the same union. On the other hand, the Political

Action Committee is in turn condemned as a

Communist-front organization because the same

James Carey, who was active in it, is said to

have been a member o f several Communist-front

organizations. [Ex. 9 for ident., J. A. 477-9.]

It was because of this history o f the Committee that the

defense was able to offer to prove through the testimony

of Representative Eberharter that the Committee had not

been engaged in obtaining information for any legislative

purposes but that it had engaged in attacking ideas with

which it disagreed, and which could not be considered

subversive, and that it was a conscious political instru

mentality directed against the New Deal. (J. A. 307-9.)

Although the government was allowed to and did intro

duce evidence with respect to testimony given before the

1 7 -

Committee during the first week o f the Washington hear

ings, ̂for the purpose o f establishing the pertinence of

questions put to Mr. Lawson, the Court on the motion of

the Government prevented the defense from putting in

other portions of that same testimony. The defendant

moved to strike the direct testimony of Congressman

Thomas on the grounds that the Court should either rule

that the question was pertinent as a matter o f law or should

permit cross-examination. The motion was denied. ( J. A.

234-44.)

The defense offered to prove that there was nothing in

American motion pictures which could be considered sub

versive or un-American or which would otherwise justify

inquiry by the Committee. Richard Griffith, a reviewer,

critic and executive director o f the National Board of

Review, was offered as a witness. Mr. Griffith has re

viewed many thousands o f films as a critic and on behalf

o f his organization, whose purpose it is to organize

audience support for meritorious pictures. Its seal is

placed on approved film. The organization has two to

three hundred community councils consisting o f represent

atives of civic, religious, educational, and cultural organi

zations. The governing body is composed o f delegates

from such organizations as the Boy Scouts of America, the

American Bar Association, the Association of American

Colleges, the National Association of Better Business

Bureaus, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the

Y. M. C. A., etc. (J. A. 266-70.) Through Mr. Griffith

the defense offered to establish that no film has ever been

produced which by any standards could be considered sub

versive. (J. A. 270-1.)

This rejected offer included review of the defendant

Lawson’s pictures. “ Action on the North Atlantic,” as

one example not only received the seal o f approval but was

classified by the organization as desirable for family or

mature audiences; it received a star as a picture especially

worth seeing and as one which had done a great service

for the American Merchant Marine. (J. A. 272.) Simi

lar offers o f proof were made with respect to all o f the

other pictures written in part or in toto by the defendant

Lawson, and particularly tô establish that in none o f

said pictures was there any single phrase or word o f

- 18-

scene which could be deemed by any standard to be sub

versive. (J. A. 273-80.)

Through producers of long standing and high repute,

through heads o f great studios, including the largest studio

in the world, through prominent writers, story analysts, and

drama critics, the defense offered to establish that there was

nothing subversive in any American motion picture.

Through the same witnesses the defense offered to estab

lish that as a matter o f undeviating practice in the motion

picture industry it is impossible for any screen writer to

put anything into a motion picture to which the executive

producers object; that the content o f motion pictures is

controlled exclusively by producers; that every word, scene

situation, character, set, costume, as well as the narrative

line and the social, political and religious significance of

the story are carefully studied, checked, edited and filtered

by executive producers and persons acting directly under

their supervision; and consequently the content o f every

motion picture is determined by the producer; and that all

o f these facts were matters of common knowledge when

defendant Lawson was subpoenaed by the House Com

mittee.

An offer to exhibit each o f the motion pictures which

the defendant Lawson had written to the Court and to

the jury was also rejected by the Court. (J. A. 309-12.)

Every Congressman before whom Lawson testified on

October 27, 1947, and a majority of the members o f the

whole Committee, and the Committee itself announced in

their official statements that they were convinced before

the defendant Lawson was put on the stand that he was

a Communist and that nothing he could have said would

change their minds. (J. A. 262-6.) [Ex. 11 for ident.,

J. A. 546.]

No part o f Lawson’s statement, which had been offered

to the Committee during the hearing, was read, given or

submitted to Congress before or during the debate on the

citation for contempt. Similarly, the defendant’s various

motions before the Committee to quash and for cross-

examination were not submitted to Congress either before

or during the debate. (J. A. 301-9.)

1 9 -

Statutes Involved.

(See Appendix A .)

Summary of Argument.

W e respectfully submit that the precise questions pre

sented by the case below, though long decided in principle

in favor of petitioner’s contentions, have never within

the framework of the facts o f this case, or any other

contempt matter, been presented to this Court and have

never been authoritatively settled.

W e urge that the questions presented are among the

most important to reach this Court in a generation. Con

scious of the breadth o f such a statement, we nevertheless

believe that the decision to be rendered in this case will

largely influence, if not determine, the course of our Re

public.

Stated in its simplest terms, the case involves inquisi

tion by means o f compulsory disclosure, carried on by a

Congressional Committee for the purpose o f ferreting

out political dissenters, and the imposition by the Com

mittee of severe penalties for dissent. On the decision in

this case may well depend the nature of our future society;

it may determine whether the time has come to abandon

principles long established or whether the time is now

here to reassert those principles.

The Committee which carries on this practice purports

to do so under color o f authority, an’ authority which, it

urges, is given to it by the Constitution. It is this con

tention that poses the question for the Court. I f this

Constitution, written by men acutely sensitive to the

iniquities o f the writs o f assistance and of test-oaths,

should contain authority for such procedure it would in

deed be a self-annihilating document. But, as the conten

tion is made on behalf of one o f the great branches of

our Government, it must and should be examined by this

Court.

The inquisitorial procedures inflicted by the Committee

were only a part o f the whole. In the very hearing cham

— 20—

bers, members of the Committee, purporting to sit as an

official body of the United States Government, directed

private employers to discharge and blacklist witnesses

whom the Committee had subpoenaed. The standards

for determination, the trial, and the punishment came

from that one body, without opportunity for intervention

by any other authority. No organ of our Government,

unless perhaps a military tribunal within sound of battle,

has laid claim to such powers. And this Court has not

determined the question before.

It is true that the powers of this Committee to issue

subpoenas and to swear witnesses has been passed on

by this Court. But this Court has yet to declare whether

this Committee in this particular hearing acted for legis

lative ends; whether it has a right to compel disclosure

o f political affiliation when in the same hearing it employs

the full resources o f its power to inflict disaster, on the

basis o f the information requested; and whether that

ultimate sanctuary, the mind o f a man, may lawfully be

invaded by temporal writ to expose dissent.

Briefly the argument on the merits may be summarized:

One of the purposes of the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth

and Tenth Amendments was to establish an absolute

privilege in the individual to form and hold private beliefs,

political and religious.

Because the right to hold beliefs is meaningless unless

the beliefs held can be expressed through association, the

privilege against governmental inquisition into belief is

also protected by the right o f freedom of association.

Being absolutely privileged, an individual’s beliefs, as

well as his associations for the purpose of expressing them,

are immune from compulsory disclosure. This immunity