Illinois v. Raby Brief and Argument for Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Illinois v. Raby Brief and Argument for Appellee, 1968. de75c4b7-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c5fddcef-7581-4cd2-a950-51aa50b73922/illinois-v-raby-brief-and-argument-for-appellee. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

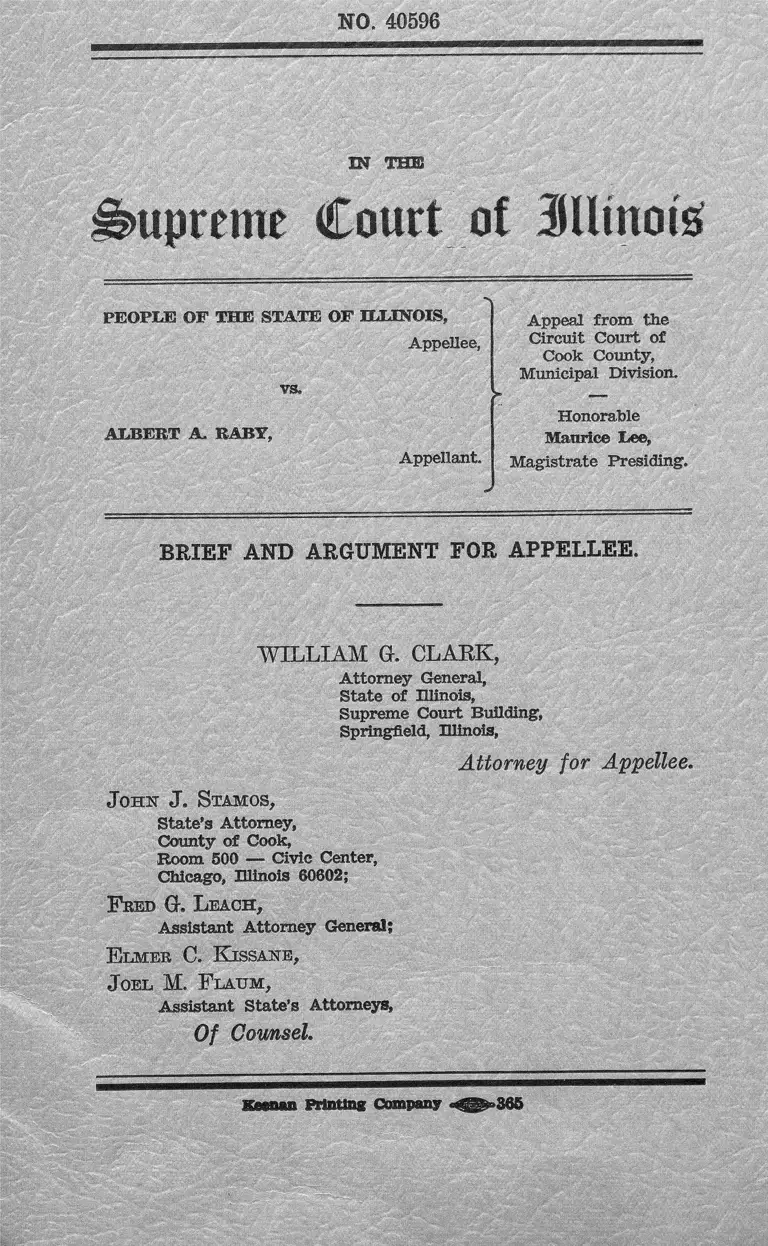

NO. 40596

IN THE

S u p re m e C o u r t of S lltn o ig

PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS.

Appellee,

vs.

ALBERT A RABY,

Appellant.

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT FOR APPELLEE.

WILLIAM G. CLARK,

Attorney General,

State of Illinois,

Supreme Court Building,

Springfield, Illinois,

Attorney for Appellee.

Joins' J. S tamos,

State’s Attorney,

County of Cook,

Room 500 — Civic Center,

Chicago, Illinois 60602;

F red G. L e a c h ,

Assistant Attorney General;

E l m e r C . R issane,

J o el M. F l a u m ,

Assistant State’s Attorneys,

Of Counsel.

Appeal from the

Circuit Court of

Cook County,

Municipal Division.

Honorable

Maurice Lee,

Magistrate Presiding.

PrlntlUK Company «^St-365

I N T H E

S u p re m e C o u r t of iU tn o to

>

PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS, Appeal from the

Appellee, Circuit Court of

Cook County,

Municipal Division.VS.

r —

ALBERT A. RABY, Honorable

Appellant. Maurice Lee,

Magistrate Presiding.

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT FOR APPELLEE.

Preliminary Statement.

The issue here, is whether . . Mr. Raby, or anyone, no

matter how laudable his aims or lofty his goals . . .

(may) . . . break the law with impunity.” (Rec. .943; Abst.

316)

At trial the defendant did not dispute the fact that he

sat or lay in the middle of a busy downtown business inter

section during the afternoon rush hour nor did he dispute

that upon his arrest he refused to voluntarily accompany

the arresting officers. Instead he admittedly went limp

and had to be carried away.

The defendant’s theory at trial was that, for technical

reasons, either the statutes, complaints, or jury instruc

tions were faulty. Further, that because of his non-violent

2

actions, good character, and his claimed admirable motiva

tion he was not guilty of collecting in a crowd, or body,

for unlawful purposes or of resisting arrest.

The People’s theory at trial was that the defendant

was guilty of disorderly conduct notwithstanding his non

violent actions, good character, and claimed admirable

motivation in that he collected along with other into a

crowd, or body, and reclined in the middle of a busy inter

section for the unlawful purpose of disrupting traffic, or

for the purpose of annoying and disturbing others in an

unreasonable manner. And further, that he wTas guilty of

resisting arrest since he refused to voluntarily accompany

the arresting officer when taken into custody.

3

POINTS AND AUTHORITIES

I .

ON THEIR FACE AND AS APPLIED, THE DISOR

DERLY CONDUCT STATUTE, ILL. REV. STAT. CH.

38, § 26 -l(a )(l) (1967), AND RESISTING ARREST

STATUTE, ILL. REV. STAT. CH. 38, § 31-1 (1967),

ARE NEITHER SO VAGUE NOR OVERBROAD AS

TO VIOLATE RIGHTS OF FREE SPEECH AND

SUBSTANTIVE OR PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS,

AS CONTAINED IN THE FIRST AND FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENTS TO THE UNITED STATES

CONSTITUTION AND ARTICLE II, SECTIONS 2

AND 4 OF THE ILLINOIS CONSTITUTION.

The Defendant, Whose Own “Hard-Core” Conduct Is

Clearly Prohibited Under Any Construction Of The Con

tested Statutes, Lacks Standing To Assert Overbreadth

Because The Statutes Do Not By Their Terms Regulate

First Amendment Freedoms.

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 554-55 (1965);

Adderly v. Florida, 385 U.S. 39, 47 (1966);

City of Chicago v. Joyce, 38 111. 2d 368, 371

(1967);

United States v. Raines, 362 U.S. 17, 21-23 (1960);

Niemotke v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268, 282 (1950);

Schneider v. New Jersey, 308 U.S. 147, 160

(1939);

City of Chicago v. Lambert, 197 N.E. 2d 448, 454

(111. 1964);

Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315, 326 (1951);

4

City of Chicago v. Gregory, 39 111. 2d 47, 60, 233

N.E. 2d 422, 429 (1968);

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131, 142, 147-48

(1966);

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963);

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496, 515-16 (1939);

Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 3-4

(1949);

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507, 509-10 (1948);

Dowbrowski v. I Mister. 380 U.S. 479, 486-87

(1965) ;

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 97-98 (1940);

Sedler, Standing to Assert Constitutional Jus

Tertii in the Supreme Court, 71 Yale L. J. 599,

613 (1962);

Kamin, Residential Picketing and the First

Amendment, 61 Nw. U. L. R. 177, 208, 223

(1966) ;

Kalven, The Concept of the Public Forum, Sup.

Ct. Rev. 1, 23-25 (1965);

Kalven, The Negro and the First Amendment,

140-60 (1965).

The Disorderly Conduct And Resisting Arrest Statutes

Are Not So Overly Broad As To Violate The Right Of Free

Speech.

United States v. Woodard, 376 F. 2d 136, 143 (7th

Cir. 1967);

Landry v. Daley, No. 67 C 1863 (N.D. 111., filed

March 4, 1968) (pp. 41-42);

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131 (1966);

Zwicker v. Boll, 270 F. Supp. 131 (D. Wise. 1967);

United States v. Jones, 365 F. 2d 675, 677 fn, 3

(2nd Cir. 1966);

5

Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315 (1951);

City of Chicago v. Gregory, Nos. 39983-84 (111.,

filed Jan. 19, 1968);

Adderly v. Florida, 385 U.S. 39 (1966);

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 559 (1965);

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963);

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284 (1963);

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961);

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965);

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 4 (1949).

The Defendant, Whose Own Hard-Core Conduct Is

Clearly Prohibited Under Any Construction Of The Dis

orderly Conduct Statute, Lacks Standing To Assert That

It Is Void For Vagueness.

United States v. Raines, 362 U.S. 17, 21 (1960);

United States v. Woodard, 376 F. 2d 136, 145 (7th

Cir. 1967);

United States v. Nat’l Dairy Corp., 372 U.S. 29,

33 (1963);

Connally v. Gen. Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385,

391 (1926);

Amsterdam, Void-For-Vagueness Doctrine in the

Supreme Court, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67, 100-101

1960);

Sedler, Standing to Assert Constitutional Jus

Tertii in the Supreme Court, 71 Yale L. J. 599,

617 (1962).

The Disorderly Conduct and Resisting Arrest Statutes

Are Not So Vague As To Violate The Right Of Due Pro

cess Of Law.

United States v. Woodard, 376 F. 2d 136, 141-

42, 145 (7th Cir. 1967);

6

Landry v. Daley, No. 67 C 1863 (N.D. 111., filed

‘March 4, 1968) (pp. 40-42);

111. Eev. Stat. ch, 38, § 26-1, Committee Comments

(Smith-Hurd, 1964);

People v. Harvey, 123 N.E. 2d 81, 83 (N.Y. Ct. of

App. 1954);

Nash v. United States, 229 U.S. 373, 377 (1913);

Boyce Motor Lines, Inc. v. United States, 342 U.S.

337, 340 (1952);

State v. Smith, 218 A. 2d 147, 151 (N.J. 1966),

cert. den. 385 U.S. 838 (1967);

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296, 308 (1940);

United States v. Petrillo, 332 U.S. 1, 7-8 (1947);

People v. Turner, 265 N.Y.S. 2d 841, 856 (Sup. Ct,

1965), aff’d 218 N.E. 2d 316 (1966), cert. den.

386 U.S. 773 (1967);

Webster’s New Twentieth Century Dictionary

(“ alarm” ) ;

Webster’s Third New International Dictionary

(“ disturb” ) ;

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131, 141-42 (1966).

People v. Knight, 228 N.Y.S. 2d 981, 987-88 (N.Y.

City Magistrates Ct, 1962);

In Re Bacon, 240 Cal. App. 2d 34; 49 Cal. Eptr.

322 (1966);

People v. Crayton, 284 N.Y.S. 2d 672 (Sup. Ct.

1967);

People v. Martinez, 43 Misc. 2d 94; 250 N.Y.S. 2d

28 (N.Y. City Crim. Ct. 1964);

Skolnick, Justice Without Trial 88 (1966);

People v. Salesi, 324 111. 131; 154 N.E. 715

(1926);

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963);

7

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965);

Collings, Unconstitutional Uncertainty—An Ap

praisal, 40 Cornell L. Q. 195, 205 (1955).

Even If The Disorderly Conduct Statute Could Not Be

Said To Embrace Adequate Due Process Standards On

Its Face, The Subject Matter Being Regulated Necessarily

Requires A Scheme Of Law Administration Involving The

Exercise Of Ad Hoc Judgment By The Police, And Be

cause Defendant Was Apprised Of The Illegality Of His

Conduct, Prior To His Arrest, He Thus Received Fair

Warning That The Conduct Was Prohibited And There

fore May Not Now Assert A Denial Of The Right To Due

Process Of Law.

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 559, 568-70 (1965);

Amsterdam, Void-For-Vagueness Doctrine in the

Supreme Court, 109 U. Pa. L. R. 67, 95 (1960);

Kamin, Residential Picketing and the First

Amendment, 61 Nw. U. L. Rev. 177, 220 (1966).

II., V.

THE DISORDERLY CONDUCT AND RESISTING AR

REST COMPLAINTS AND JURY INSTRUCTIONS

WERE NOT ERROR SINCE THEY ADEQUATELY

INSTRUCTED THE DEFENDANT AND THE JURY

OF THE NATURE AND THE ELEMENTS OF THE

OFFENSES CHARGED AND IN NO WAY PREJU

DICED HIS DEFENSE.

THE COMPLAINTS

City of Chicago v. Joyce, 38 111. 2d 368 ; 232 N.E.

2d 289 (1967);

City of Chicago v. Lambert, 47 111. App. 2d 151;

197 N.E. 2d 448 (1964);

8

People v. Woodruff, 9 111. 2d 429; 137 N.E, 2d 809

(1957);

People v. Nastario, 30 111. 2d 51; 195 N.E. 2d 144

(1963);

Smith v. United States, 360 U.S. 1, 9; 79 S. Ct.

991, 996 (1959);

38 S.H.A. § 26-1 (a), Committee Comments (1967);

United States v. Woodard, 376 F. 2d 136 (7th Cir.

1967);

People v. Brown, 336 111. 257, 258-259; 168 N.E.

289 (1929);

People y. Collins, 35 111. App. 2d 228; 182 N.E.

2d 387 (1963);

People v. Peters, 10 111. 2d 577; 414 N.E. 2d 9

(1957);

People v. Williams, 30 111. 2d 125; 196 N.E. 2d

483 (1963);

People v. Flynn, 375 111. 366; 31 N.E. 2d 591

(1941).

THE INSTRUCTIONS

People v. Knight, 35 Misc. 2d 218; 228 N.Y.S. 2d

981 (N.Y. City Magistrates Ct. 1962);

Landry v. Daley, No. 67 C 1863 (N.D. 111., filed

March 4, 1968);

People v. Crayton,------Misc, 2 d ------- ; 284 N.Y.S.

2d 672 (Sup. Ct, 1967);

In Re Bacon, 240 Cal. App. 2d 34; 49 Ca, Rptr.

322 (1966);

People v. Martinez, 43 Misc. 2d 94; 250 N.Y.S. 2d

28 (N.Y. City Crim. Ct. 1964);

Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1; 69 S.

Ct. 894 (1949); '

People v. Davis, 74 111. App. 2d 450; 221 N.E. 2d

63 (1966).

9

THE AMENDMENT OF THE COMPLAINT DID NOT

VIOLATE THE DEFENDANT’S RIGHTS SINCE THE

STRICKEN PORTION CONSTITUTED A MERE

FORMAL DEFECT TO AN OTHERWISE CLEAR

AND UNAMBIGUOUS CHARGE.

Illinois Revised Statutes, Chapter 38, §§ 7-7, 31-1

and 111-5;

People v. Mamolella, 85 111. App. 2d 240, 229 N.E.

2d 320 (1967);

Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion ;

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution ;

Article II, §§ 2 and 9 of the Illinois Constitution.

I I I .

I V .

THE ADMISSION OF THE STATE’S AMENDED LIST

OF WITNESSES DID NOT VIOLATE THE DEFEND

ANT’S RIGHTS SINCE THE WITNESSES WERE

PREVIOUSLY UNKNOWN TO THE STATE AND

SINCE HE HAS NOT SHOWN HOW PRIOR KNOWL

EDGE OF THEIR IDENTITIES WOULD HAVE BET

TER ENABLED HIM TO MEET THEIR TESTI

MONY.

Illinois Revised Statutes, Chapter 38, § 114-9;

People v. O’Hara, 332 111. 436, 447, 466, 163 N.E.

804 (1928);

People v. Weisberg, 396 111. 412, 421, 71 N.E. 2d

671 (1947);

10

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965);

Douglas v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 415 (1965);

United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967);

Sixth Amendment to dhe United States Constitu-

tion;

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution ;

Article II, 2 and 9 of the Illinois Constitution.

¥ 1 .

DEFENDANT’S CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT OF DUE

PROCESS WAS NOT INFRINGED BY THE TRIAL

COURT’S REFUSAL TO ADVISE THE JURY THAT

THEY WOULD HAVE TO ASCERTAIN DEFEND

ANT’S STATE OF MIND BY LOOKING TO HIS CON

DUCT, OR BY THE COURT’S REFUSAL TO IN

STRUCT THE JURY AS TO DICTIONARY MEAN

INGS OF THE RESISTING ARREST STATUTORY

LANGUAGE “ RESISTS OR OBSTRUCTS”, BECAUSE

THE SUBJECT MATTER OF BOTH TENDERED IN

STRUCTIONS WAS EMBRACED IN OTHER GIVEN

INSTRUCTIONS.

People v. Fernow, 286 111. 627, 630, 122 N.E. 155

(1919);

People v. Billardello, 319 111. 124, 149 N.E. 781

(1925);

Landry v. Daley, No. 67 C 1863 (N.D. 111., filed

March 4, 1968);

111. Rev. Stat., ch. 38, § 115-4(a) (1967);

People v. Bruner, 343 111. 146, 158, 175 N.E. 400

(1931);

People v. 'Cavaness, 21 111. 2d 46, 171 N.E. 2d 56

(1961);

11

People v. Thompson, 81 111. App. 2d 263, 226 N.E.

2d 80 (1967);

C.J.S. Criminal Law § 1190(a), at 476-77 (1961);

People v. Lyons, 4 111. 2d 396, 122 N.E. 2d 809

(1954);

Hall v. Chicago & N. W. Ry., 5 111. 2d 135, 125

N.E. 2d 77 (1955);

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242, 263 (1937).

V I I .

DEFENDANT’S INSTRUCTION NUMBER 10 WAS

CORRECTLY EXCLUDED SINCE IT WAS DUPLICI

TOUS AND ERRONEOUS IN ITS INCLUSION OF A

REFERENCE TO A WITNESS’S FINANCIAL IN

TEREST IN THE RESULT OF THE CASE.

Lauder v. People, 104 111. 248 (1882);

People v. Provo, 409 111. 63, 97 N.E. 2d 802, 806,

807 (1951);

2d 438, 442 (1965).

People v. Laczny, 63 111. App. 2d 324, 211 N.E.

V I I I .

THE TRIAL COURT DID NOT ERR IN ITS INSTRUC

TIONS RELATIVE TO THE WITNESS’S “IN

TERESTS” SINCE BOTH MEANINGS OF THAT

TERM WERE ADEQUATELY CONVEYED TO THE

JURY WITHOUT PREJUDICE TO THE DEFEND

ANT.

People v. Corbishly, 327 111. 312, 158 N.E. 732

(1927);

People v. Solomen, 261 III. App. 585 (1931);

People v. Emerling, 341 111. 424, 173 N.E. 474

(1930);

People v. Provo, 409 111. 63, 97 N.E. 2d 802

(1951);

People v. Laezny, 63 111. App. 2d 324, 211 N.E. 2d

438, 442 (1965).

I X .

THE TRIAL COURT DID NOT PREJUDICIALLY ERR

IN EXCLUDING THE TESTIMONY OF A DEFENSE

WITNESS, MR. LETHERER, AFTER THE COURT

HAD RULED THAT ALL WITNESSES BE SE

QUESTERED, SINCE MR. LETHERER WAS PRES

ENT IN THE COURT ROOM DURING THE TESTI

MONY OF PROSECUTION WITNESSES PRIOR TO

HIS BEING CHOSEN AS A WITNESS AND SINCE,

TO THE EXTENT THAT MR. LETHERER’S TESTI

MONY WAS NOT IMMATERIAL AND IRRELEV

ANT, IT WAS CUMULATIVE.

6 Wigmore, Evidence, §§ 1837-1839, 1908 (3rd ed.

1940);

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38, §' 109-3 (b) (1967);

Annotation, 32 A.L.R. 2d 358.

People v. Dixon, 23 111. 2d 136; 177 N.E. 2d 206

(1961);

People v. Mack, 25 111. 2d 417; 185 N.E. 2d 154

(1962);

Annotation, 14 A.L.R. 3d 16;

Palmer v. People, 112 111. App. 527 (1903);

Ewing v. Cox, 158 111. App. 25 (1910);

Kota v. People, 136 111. 655; 27 N.E. 53 (1891);

Bnlliner v. People, 95 111. 394 (1880).

13

X .

THE COURT PROPERLY EXERCISED DISCRETION

IN EXCLUDING THE TESTIMONY OF V/ITNESSES

REGARDING ALLEGED POLICE BRUTALITY

SINCE THE SUBJECT WAS OUTSIDE OF THE

SCOPE OF THE DIRECT EXAMINATION OF MR.

BECKER AND OFFICER KARCHESKY AND SINCE

THE SUBJECT WAS IMMATERIAL AND IRRELE

VANT TO THE ISSUES OF THE CASE.

Veer v. Hagemann, 334 111. 23, 165 N.E. 175

(1929);

People v. Kirkwood, 17 111. 2d 23, 29; 160 N.E.

2d 766 (1959);

People v. Simmons, 274 111. 528; 113 N.E. 887

(1916);

People v. Halteman, 10 111. 2d 74; 139 N.E. 2d 286

(1957);

3 Wigmore, Evidence §§ 944, 983 (2) (3rd ed.

1940);

People v. DuLong, 33 111. 2d 140, 144 ; 210 N.E.

2d 513 (1965);

People v. Matthews, 18 111. 2d 164; 163 N.E. 2d

469 (1959);

People v. Smith, 413 111. 218; 108 N.E. 2d 596

(1952);

People v. DelPrete, 364 111. 376, 379-380; 4 N.E.

2d 484 (1936);

People ex rel. Noren v. Dempsey, 10 111. 2d 288;

139 N.E. 2d 780 (1957);

People v. Lettrick, 413 111. 172; 108 N.E. 2d 48S

(1952);

People v. Shines, 394 111. 428; 68 N.E. 2d 911

(1946).

14

X I .

THE COURT PROPERLY SENTENCED THE DEFEND

ANT ON BOTH THE DISORDERLY CONDUCT

CHARGE AND THE RESISTING ARREST CHARGE

SINCE THEY ARE SEPARATE AND DISTINCT

CRIMES AND INVOLVED DIFFERENT CONDUCT.

People v. Ritchie, 36 111. 2d 392, 397; 222 N.E.

2d 479 (1967);

People v. Ritchie, 66 111. App. 2d 302; 213 N.E.

2d 651 (1966);

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38, § 1-7 (m) (1967);

People v. Colson, 32 111. 2d 398; 207 N.E. 2d 68

(1965);

People v. Squires, 27 111. 2d 518; 190 N.E. 2d 361

(1963);

People v. Schlenger, 13 111. 2d 63; 147 N.E. 2d

316 (1958).

X I I .

THE DEFENDANT’S CLAIM OF UNREASONABLE

BAIL CANNOT ARISE ON AN APPEAL FOR RE

VERSAL SINCE THE DEFENDANT HAS FAILED

TO PURSUE HIS PROPER STATUTORY REMEDY.

Illinois Revised Statutes, Chapter 38, M 110-4,

110-6 and 110-7;

People v. Lalor, 290 111. 234, 124 N.E. 866 (1920);

Illinois Supreme Court Rules 361, 606 and 609;

Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion.

15

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution.

Article II. §§ 2 and 7 of the Illinois Constitution.

X I I I .

THE SENTENCES OF THE TRIAL COURT ARE NOT

EXCESSIVE NOR OUT OF PROPORTION TO THE

NATURE OF THE OFFENSES.

People v. Taylor, 33 111. 2d 417, 424, 211 N.E. 2d

673, 677 (1965);

People v. Smith, 14 111. 2d 95, 97, 150 N.E. 2d 815,

817 (1958);

Helperin, Appellate Review of Sentence in Illi

nois—Reality or Illusion?, 55 111. B. J. 300, 301

fn. 6 (1966).

16

A R G U M E N T

I.

ON THEIR FACE AND AS APPLIED, THE DISOR

DERLY CONDUCT STATUTE, ILL. REY. STAT. CH.

38, $ 26-1 (a)(1) (1967), AND RESISTING ARREST

STATUTE, ILL. REV. STAT. CH. 38, § 31-1 (1967),

ARE NEITHER SO VAGUE NOR OVERBROAD AS

TO VIOLATE RIGHTS OF FREE SPEECH AND

SUBSTANTIVE OR PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS,

AS CONTAINED IN THE FIRST AND FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENTS TO THE UNITED STATES

CONSTITUTION AND ARTICLE II, SECTIONS 2

AND 4 OF THE ILLINOIS CONSTITUTION.

The Defendant, Whose Own “ Hard-Core” Conduct Is

Clearly Prohibited Under Any Construction Of The Con

tested Statutes, Lacks Standing To Assert Overbreadth

Because The Statutes Do Not By Their Terms Regulate

First Amendment Freedoms.

There is surely very little dissent with the general

proposition that individuals are privileged by the First

Amendment to use the medium of peaceful demonstrations

for the purpose of voicing their protest, merited or other

wise, against claimed social or governmental injustices.

And if in the process of exercising that right, spectators

become disturbed or alarmed, the demonstration will

nevertheless continue to be protected for the reason that

free speech has as one of its high purposes just such a re

sult. Termini ello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 4 (1949).

The theoretical postulate for the right of free speech is

to promote the placement of varying views before the

17

public in the marketplace of ideas, so that the majority

may be persuaded as to the error in their thinking or the

minority shown the faults in their dissent, with the end

result that some particular policy judgment will more

closely reflect the thought-out wisdom generated by the

democratic process, thereby encouraging the peacefulness

of change and the responsiveness of government to gov

erned. But where the record divulges evidence of more

than mere alarm or disagreement among the spectators,

so that there exists an imminent threat of violence, to

still unhesitatingly uphold the demonstrators’ conduct as

free speech, pure and simple, is to ignore its other face:

incitement to riot. Even here, however, the law requires

more. The police must make all reasonable effort to pro

tect the protestors from the angry crowd because it is their

duty to maintain order, Hague v. CIO, 307 U.S. 496, 516

(1939), Feiner v. New York, 340 TT.S. 315, 326 (1951) (dis

senting opinion of Mr. Justice Black), but if the circum

stances warrant the belief that, in spite of the officers’ at

tempts, a breach of the peace will likely ensue, it is in

cumbent upon the police to demand that the demonstrators

end their protest, accompany that demand with an explana

tion if time permits, and arrest those unwilling to desist.

City of Chicago v. Gregory, 39 111. 2d 47, 60, 233 N.E. 2d

422, 429 (1968). This resolution of the problem has,

as already stated, been termed the “Heckler’s Veto”,

by Professor Kalven of the University of Chicago.

Kalven, The Negro and the First Amendment 140-60

(1965). Call it what you will, the law does not contem

plate standing by until a riot occurs, City of Chicago v.

Lambert, 197 N.E. 2d 448, 454 (111. 1964), and in most

street-riots it is not feasible to attempt arrest of the heck

lers either because of the highly incendiary emotions of

the crowd or because of inadequate police personnel on

18

the scene. Kamin, Residential Picketing and the First

Amendment, 61 Nw. U. L. Rev. 177, 223 (1966). “ There

are circumstances when the requirements of community or

der may necessitate the arrest of the speakers or the

marchers, rather than of the members of the crowd who

would do them violence for otherwise protected and privi

leged conduct.” Id. at 220.

All these various conditions which must be satisfied

prior to an arrest for disorderly conduct if it is to pass

constitutional muster, are cited here merely to emphasize

and contrast the position in which the defendant finds

himself. As a pre-condition, some form of constitutionally

protected conduct is presumed, and on this point the de

fendant does not begin to qualify. There is no right to

stand or sit in the middle of a rush-hour street intersection

in a major city regardless of how lofty the demonstrators’

claimed motives may be. Freedom of speech is not so per

missive as to allow every opinionated individual to address

a group in any public place at any time. While the content

of speech undoubtedly may not be tampered with, the

“when’s” , “where’s”, and “how’s” of free speech are subject

to a limited degree of regulation. Adderly v. Florida, 385

U.S. 39, 47 (1966). The procedures of free speech, unlike

the substance, are not absolute. Mr. Justice Goldberg em-

phosized this distinction nearly three years ago:

The right of free speech and assembly, while funda

mental in our democratic society, still do not mean

that everyone with opinions or beliefs to express may

address a group at any public place and at any time.

The constitutional guarantee of liberty implies the

existence of an organized society maintaining public

order, without which liberty itself would be lost in

the excesses of anarchy. . . . One would not be justi

fied in ignoring the familiar red light because this

19

was thought to be a means of social protest. Nor

could one, contrary to traffic regulations, insist upon

a street meeting in the middle of Times Square at the

rush hour as a form of speech or assembly. Cox v.

Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 554-55 (1965) (Emphasis

supplied).

One writer has analogyzed the demonstrator’s rights to an

individual wanting to speak at a meeting conducted under

Robert’s Rules of Order. In this vernacular, defendant

is “ out of order” . Kalven, The Concept of the Public

Forum, Sup. Ct. Rev. 1, 23-25 (1965). Another author puts

it this way: “ It is my position that the constitutional

status of a grievance does not give first amendment pro

tection to every form utilized to air it. Sitting down in

Times Square or at the intersection of State and Madison,

however lofty the objectives of the demonstrators may

be, cannot be supported by constitutional privilege.” Ka-

min, Residential Picketing and the First Amendment, 61

Nw. U. L. Rev. 177, 208 (1966). Granted that the streets

do represent an invaluable public forum for “purposes of

assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and

discussing public questions . . . ,” Hague v. C.I.O., 307

U.S. 496, 515 (1939), and that a blanket, uniform, and

nondiscriminatory prohibition against all parades and

meetings upon all streets would likely be unconstitutional,

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 555 fn. 13 (1965), surely

even the most avowed critic of governmental regulation

will acknowledge that the traveling public has as much a

claim to the use of the streets in a transportation function,

especially a major thorough-fare or busy intersection, as

would the demonstrator in a forum function. Indeed, to

deny the transport function would be a breach of the

public trust. Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268, 282

(1950); Schneider v. New Jersey, 308 U.S. 147,160 (1939).

20

The United States Supreme Court, at least, does not

consider the defendant’s conduct to be constitutionally pro

tected. Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 554-55 (1965).

And this court’s recent decision in City of Chicago v.

Joyce, 38 111. 2d 368, 371 (1967), illustrates an identical

attitude. This Court there decided that when the defend

ant sat down on the sidewalk in front of Chicago’s City

Hall, thereby obstructing pedestrian traffic as well as

the entrance to the building, she could not be heard to

sanction the conduct as an exercise of free speech. “ These

rights do not mean that everybody wanting to express

an opinion may plant themselves in any public place at

any time and engage in exhortations and protest without

regard to the inconvenience and harm it causes the pub

lic.” Whether one immobilizes city hall or city traffic,

that conduct can not be clothed with constitutional garb.

What is left, then, of the defendant’s free speech claim?

His own conduct being indefensible, lie must resort to the

evasion that the Disorderly Conduct and Resisting Ar

rest statutes are overly broad, not as to him of course,

but as to other individuals. The overbreadth doctrine, if

successfully employed, states that any statute . . in

form, and as interpreted, [which permits] within the scope

of its language the punishment of incidents fairly within

the protection of the guarantee of free speech is void, on

its face, as contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment.” Win

ters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507, 509-10 (1948). The over

breadth may stem from deliberate and quite precise word

ing in the statute, or it may arise out o f vagueness of

some or all of the statutory terms. It is a first amendment-

substantive due process doctrine created to provide an ex

ception to the general rule of “ standing” that one may

not constitutionally challenge a statute, valid as to the

challenger, on the theory that it violates the rights of a

21

third party. United States v. Baines, 362 U.S. 17, 21-23

(1960). The rationale for the “ standing” requirement lies

in the broad constitutional mandate to decide only cases

or controversies, and in the more narrow common-sense

guide that the courts should never anticipate a question

of constitutional law in advance of the grave necessity for

deciding it or attempt to formulate a rule broader than

required by the precise facts to which it is to be ap

plied. Id. at 21. The logic for the exception to the gen

eral rule, in free expression cases, is that the challenger

must be given standing in order to enable the court to

vindicate the in terrorem or chilling effect which the

statute may have on third persons who are not otherwise

represented in court and who avoid the advocacy of all

forms of free speech that might arguably be prohibited

by the unconstitutional statute, by itself or as construed,

in order to preclude their being prosecuted subsequently.

See Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 97-98 (1940);

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, 486-87 (1965). Where

a criminal statute regulating expression is challenged

as overlybroad, the policy reasons basic to the whole con

cept of free speech outweigh those policies which inhere

in the general rules of standing.

As pointed out, however, by Professor Robert A. Sedler

of St. Louis University in 71 Yale L. J. 599, 613 (1962)

(“ Standing to Assert Constitutional Jus Tertii in the

Supreme Court” ), the Supreme Court has ignored the

particular conduct of the challenger only when the statute

by its terms regulated the exercise of expression. He dis

tinguishes that situation from one where a statute not

prohibiting expression as such can arguably be related

or applied to the exercise of expression, and concludes

that in the latter context the Court proceeds from tradi

22

tional rules of standing, because here the in terrorem ef

fect on expression is so much diminished as to knock out

the basis for ignoring the time-honored rules on stand

ing. Supreme Court cases bear out this analysis. For

example, in Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229

(1963), the Court invalidated the state’s common law

crime of breach of the peace, directed at disorderly con

duct rather than protected speech, but only after it had

concluded that the particular conduct sought to be pro

hibited was constitutionally protected. In Thornhill v.

Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940), however, the Court looked

only to the words of the statute without considering Thorn

hill’s conduct, and found it unconstitutional in as much

as it sought to prohibit all peaceful picketing. Thornhill,

unlike Edwards, involved a statute which by its terms

regulated First Amendment freedoms. In Terminiello v.

Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 3-4 (1949), the Court invalidated a

breach of the peace ordinance construed by the trial court

as punishing speech which “ stirs the public to anger,

invites dispute, brings about a condition of unrest, or cre

ates a disturbance,” even though the defendant’s own

conduct apparently amounted to “ fighting words”, which

are not constitutionally protected. Because the Court

noted that one of the functions of free speech is to create

dispute, a conviction on any of the grounds designated

would have violated the First Amendment, and therefore

the case obviously falls into the “by its terms” (here, the

trial court’s construction) category. Cox v. Louisiana, 379

U.S. 536 (1965), involved the very same statute which the

Court had passed upon in Edwards, and again the Court

first looked to the conduct involved to determine whether

it could be constitutionally punished before invalidating

the convictions. At the end of the opinion relating to the

breach of the peace prosecution, 379 U.S. 536, 551 (1965),

the Cox Court appended an overbreadth discussion as an

additional factor in disposing of the case as it did. Be

cause the Louisiana Supreme Court had defined “breach

of the peace” as “to agitate, to arouse from a state of

repose, to molest, to interrupt, to hinder, to disquiet,” and

because that same court had permitted the statute’s ap

plication to the defendants in that case, the United States

Supreme Court saw the statute as being akin to the Ter-

miniello offense, one which “by its terms” regulated free

expression. That explains the Cox Court’s invocation of

the overbreadth doctrine. It is still significant, however,

that the Cox Court felt constrained to devote the vast

majority of its opinion to a factually-laden discussion of

the defendants’ conduct. In Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S.

131, 142 (1966), the Court was again confronted with a

breach of the peace statute (the term was, as in Illinois,

not defined in the statute, the latter making it unlawful

to congregate in a public place “ with intent to provoke

a breach of the peace” ) and again, because it did not by

its terms regulate expression, looked first to the special

facts of the case before overturning the convictions on

the alternative grounds that no violation was shown by

the evidence, and that the “ statute can not constitutionally

be applied to punish petitioners’ actions in the circum

stances of this case.” Ibid. Mr. Justice Brennan, concur

ring, was the only member to broach the overbreadth doc

trine, his reason being that “ [It] suffices that petitioners’

conduct, was arguably constitutionally protected and was

‘not the sort of hard core conduct that would obviously

be prohibited under any construction’, Dombrowski v.

Pfister, 380 U.S. at 491-92, of § 14:103.1.” Id. at 147-48.

If one assumes that Mr. Justice Brennan eschews the

by its terms analysis, even under his interpretation of

24

the overbreadth doctrine, defendant here could not suc

cessfully argue overbreadth because his is the sort of hard

core conduct which Justice Brennan tells us deprives him

of the privilege to argue rights of third parties.

What the State’s argument then boils down to is simply

that the Disorderly Conduct and Besisting Arrest statutes

do not by their terms attempt to regulate first amend

ment freedoms, and that therefore the overbreadth doc

trine may not be invoked unless the statutes have been

unconstitutionally applied. Defendant’s own conduct not

being privileged as free speech, traditional “ standing”

theory forbids his evasiveness in arguing rights of third

parties. Defendant may not be heard, therefore, to as

sert that the challenged statutes stand in violation of the

First Amendment.

The Disorderly Conduct And Resisting Arrest Statutes

Are Not So Overly Broad As To Violate The Right Of Free

Speech.

But assume arguendo he is heard. In that event, the

court must be made cognizant of a number of factors, one

of which is that the plaintiff is not urging an interpreta

tion of the statutes which would result in a proscription of

first amendment freedoms. Nor is it thought that this Court

will construe the statutes to have that effect, reliance

being placed on the recent decision of City of Chicago

v. Gregory, 39 111. 2d 47, 60, 233 N.E. 2d 422, 429 (1968),

where this court’s extreme caution in applying Chicago’s

Disorderly Conduct ordinance in such a way as to avoid all

constitutional friction, evidences a recognition of the

court’s responsibility to limit the statutes involved in the

instant case to constitutionally proscribable conduct. The

Federal District Court for the Northern District of Illi

nois (E.D. in Landry v. Daley, No. 67 C 1963 (N.D. 111.,

25

filed March 4, 1968), has sustained the constitutional va

lidity of the Illinois Desisting Arrest statute, when chal

lenged as overlybroad, by giving it a “ reasonable and na

tural construction” and concluding that “ this statute is

not directed at peaceful assembly” , (pp. 41-42 of opinion).

In United States v. Woodard, 376 F. 2d 136, 143 (7th Cir.

1967), the Seventh Circuit specifically upheld the Illinois

Disorderly Conduct statute as constitutional when attacked

for overbreadth, by reasoning that there was no cause to

assume that the Illinois Courts would apply the statute to

protected activities, and observing that the District Court

had narrowly applied the statute to conduct which could,

not be construed as priviliged under a free speech cloak:

The defendants, citing decisions such as Brown v.

State of Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131, 86 S. Ct. 719, 15

L. Ed. 2d 637 (1966); Cox v. State of Louisiana,

supra; Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229, 83

S. Ct. 680, 9 L. Ed. 2d 697 (1963); Garner v. State

of Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157, 82 S. Ct. 248, 7 L. Ed.

2d 207 (1961); and Terminiello v. City of Chicago,

337 U.S. 1, 69 S. Ct. 894, 93 L. Ed.‘ 1131 (1949),

point to the threat to first amendment freedom occa

sioned by the discriminatory application of broadly

worded statutes designed to maintain public order.

In the cases cited, statutes and ordinances were struck

down insofar as the facts disclosed that the laws had

been applied or construed to allow conviction for the

exercise of first amendment rights. The situation here

is entirely different. The defendants’ conduct was

not constitutionally protected and the statute was

properly and narrowly applied. It cannot be contend

ed that the Illinois statute is constitutionally infirm

for the reason that it may possibly be misapplied to

include protected activity. We have no warrant to

assume that the Illinois courts will construe the

statute improperly or that they will not interpret

the statute as we have done. The state courts are

26

as firmly bound by the Constitution as the federal

courts.

With these various factors at hand, and noting that the

Illinois Disorderly Conduct and Resisting Arrest statutes

have not been applied by the trial court in this case to

conduct which might be privileged under a First Amend

ment gloss, we fail to see how the defendant can truth

fully assert that they are overbroad because they have

been, are being, or will be applied to proscribe constitu-

tiionally protected activities, or that they exert an in

terrorem and chilling effect on the exercise of free speech.

Defendant might present a stronger case if the Disorderly

Conduct statute proscribed merely those acts which “ alarm

or disturb another”, without more, for Terminiello v.

Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 4 (1949), would then apply so as to

void the statute. But the language is qualified. The acts

must also be unreasonable and must be such as to pro

voke a breach of the peace. When all these circumstances

are present, and the requirements of City of Chicago v.

Gregory, are satisfied where applicable, no constitutional

infirmity exists in punishing the actor. Brown v. Louisiana,

383 U.S. 131 (1966); Feiner v. New York, 340-TJ.S. 315

(1951); (see first sub-point of this section). A three-judge

court in Zwicker v. Boll, 270 F. Supp. 131 (D. Wise. 1967)

took the very same tact as used in Woodard, namely that

the Wisconsin Disorderly Conduct Statute (punishing those

who engage in “violent, abusive, indecent, profane, bois

terous, unreasonably loud, or otherwise disorderly conduct

under circumstances in which such conduct tends to cause

or provoke a disturbance” ) had not been, nor was there

cause to believe it would be, construed by the Wisconsin

courts as regulating protected expression, and that the

state statute could properly be used, to punish the de

fendants for interfering with DOW Chemical Company’s

27

interviews at the University of Wisconsin. The Second

Circuit in United States v. Jones, 365 F. 2d 675, 677 fn.

3 (2d Cir. 1966), disposed of an overbreadth challenge

made to New York’s Disorderly Conduct statute by simply

denying defendant standing to make that attack, where

his own conduct was not protected and the New York

Court of Appeals had restricted the application of the

statute (defining “breach of the peace” as performing

acts “ in such a manner as to annoy, disturb, interfere

with, obstruct, or be offensive to others . . .” ) to conduct

lying outside the protection of the First Amendment.

Finally, most of the first amendment eases cited by the

defendant as buttressing authority for his overbreadth

challenge, involved peaceful and legitimate protests against

various injustices, not the least of which was racial dis

crimination in public areas or places of service. They in

volved statutes purporting to regulate or prohibit certain

conduct, but factually applied in the case itself in such a

manner as to interfere with what the United States Su

preme Court found to be privileged expression. By way

of illustration, Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961);

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 US. 229 (1963); Wright

v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284 (1963); and Cox v. Louisiana,

379 U.S. 536 (1965), all involved first amendment conduct

which the states attempted to prohibit under one guise or

another. Where, on the other hand, the statutes were nar

rowly applied to activity falling outside the protections of

the first amendment, as is also true in the instant case,

the Court upheld their validity: Feiner v. New York, 340

U.S. 315 (1951); Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 559 (1965)

(picketing “near” a courthouse prosecution); and Adderly

v. Florida, 385 U.S. 39 (1966) (prosecution for “ trespass

upon the property of another with a malicious and mischie

vous intent” ; defendants had demonstrated on a jailhouse’s

private delivery entrance).

The Defendant, Whose Own Hard-Core Conduct Is

Clearly Prohibited Under Any Construction Of The Dis

orderly Conduct Statute, Lacks Standing To Assert That

It Is Void For Vagueness.

Regarding defendant’s procedural due process argu

ment that the Illinois Disorderly Conduct statute is un

constitutionally vague, everyone will agree with him that

“ a statute which either forbids or requires the doing of

an act in terms so vague that men of common intelli

gence must necessarily guess at its meaning and differ

as to its application, violates the first essential of due

process. . . .” Connally v. General Construction Co., 269

U.S. 385, 391 (1926). “When a statute is attacked on

vagueness grounds under the due process clause of the

first or fourteenth amendments, the theory of the attack

is that the party against whom the statute is to be ap

plied did not receive fair warning that his conduct was

prohibited.” Sedler, Standing to Assert Constitutional Jus

Tertii in the Supreme Court, 71 Yale L.J. 599, 617 (1962).

If nothing else, at the very least, the Disorderly Con

duct statute surely prohibits an individual’s sitting down

in the middle of Randolph and La Salle streets during a

typical rush hour. It may be vague as to a thousand other

acts but not as to that singular feat of defiance for which

the defendant was convicted in the lower court. A reason

able man simply could not doubt that act was pro

hibited. Such being the case, how then does defendant

complain of a lack of notice? His own conduct being

clearly illegal, his argument lowers itself to the proposi

tion that the vagueness does exist for other acts by other

persons. Under typical rules of standing, however, he

may not assert the rights of third persons. United States

v. Raines, 362 U.S. 17, 21 (1960). If the vagueness in

quiry necessarily changes the “ standing” rules, it does not

altogether dispense with their propriety. The vagueness

analysis simply shifts “the standing question from 'are

you within the scope of constitutional immunity’ to ‘are

you within the scope of statutory indefiniteness?’ To chal

lenge a statute as vague or overreaching, a litigant must

still be one as to whom it is vague or whom it may over

reach.” Amsterdam, Void-For-Vagueness Doctrine in the

Supreme Court, 109 U. Pa. L.R. 67, 100-101 (1960); see

also United States v. National Dairy Corporation, 372

U.S. 29, 33 (1963), where the Court ignored a vagueness

attack upon § 3 of the Robinson-Patman Act, making it a

crime to sell goods at “unreasonably low prices for the

purpose of destroying competition” , because the defend

ant’s selling at below-cost prices was the sort of hard

core conduct which at the very least was intended to be

proscribed. As to the defendant Raby, then, no vagueness

existed and he may not, therefore, claim immunity from

prosecution on the ground that he did not receive fair

warning that his conduct was prohibited. “Because of the

‘hard-core’ nature of these violations, it is clear that de

fendants had notice that their activities were within the

ambit of the Illinois statute and therefore cannot success

fully assail its purported vagueness.” United States v.

Woodard, 376 F. 2d 136, 145 (7th Cir., 1967) (concur

ring opinion).

The Disorderly Conduct and Resisting Arrest Statutes

Are Not So Vague As To Violate The Right Of Due Pro

cess Of Law.

Defendant’s vagueness attack on the Disorderly Con

duct statute centers upon the following italicized language:

30

“A person commits disorderly conduct when he know

ingly does any act in such unreasonable manner as to

alarm or disturb another and to provoke a breach of the

peace.” 111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38, § 26-l(a )(l) (1967). His

challenge to the Resisting Arrest -statute is concerned with

the term “ resists or obstructs” : “A person who

knowingly resists or obstructs the performance by one

known to the person to be a peace officer of any au

thorized act within his official capacity shall be fined not

to exceed $500 or imprisoned in a penal institution other

than the penitentiary not to exceed one year, or both.”

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38, § 31-1 (1967). The broad defect com

mon to both laws, it is suggested by the defendant (p. 23

of defendant’s brief), is that they vest the officer with

unbridled discretion to act out his prejudices upon mi

nority and disadvantaged peoples.

The latter argument has already been answered in the

State’s reply to the overbreadth challenge. (See second sub-

point of this section). As for the asserted indefiniteness of

the use of “unreasonable” in the Disorderly Conduct pro

vision, the term could just as ŵ ell have been deleted and

the law would have implied its presence: “ Common sense

. . . dictates that . . . conduct is to be adjudged to be dis

orderly, not merely because it offends some -supersensitive

hypercritical individual, but because it is, by its nature,

of a sort that is a substantial interference -with (our old

friend) the reasonable man.” People v. Harvey, 123 N.E.

2d 81, 83 (N.Y. Ct. of App. 1954). To attempt a defini

tion would be to attempt the impossible. There is no singu

lar across-the-board interpretation which could be devised

to cover the infinite number of factual situations to which

the term is intended to have relation. As used in the

statute, “unreasonable” inherently assumes a prospective

specific setting or circumstance which is to be correlated

31

to some particular norm involved. Whether the defend

ant’s conduct measures up to this norm, is a question to

be decided in each individual case through the fact-finding

process. This method of determining culpability has

never met with dissent and has been affirmed by no less a

Justinian than Mr. Justice Holmes: “ [T]he law is full of

instances where a man’s fate depends on his estimating

rightly, that is, as the jury subsequently estimates it,

some matter of degree.” Nash v. United States, 229 U.S.

373, 377 (1913); see also Codings, Unconstitutional Un

certainty—An Appraisal, 40 Cornell L. Q. 195, 205 (1955).

The drafters to the Illinois Criminal Code were fully

aware of the foppery in suggesting that the term be given

meaning:

§ 26-1 (a) is a general provision intended to encom

pass all of the usual types of “disorderly conduct”

and “ disturbing the peace” . Activity of this sort is so

varied and contingent upon surrounding circumstances

as to almost defy definition. Some of the general

classes of conduct which have traditionally been re

garded as disorderly are here listed as examples:

the creation or maintenance of loud and raucous

noises of all sorts; unseemly, boisterous, or foolish

behavior induced by drunkenness; threatening damage

to property or indirectly threatened bodily harm

(which may not amount to assault); carelessly or

recklessly displaying firearms or other dangerous in

struments; preparation for engaging in violence or

fighting; and fighting of all sorts. In addition, the task

of defining disorderly conduct is further complicated

by the fact that the type of conduct alone is not de

terminative, but rather culpability is equally depend

ent upon the surrounding circumstances. * * * These

considerations have led the Committee to abandon

any attempt to enumerate “ types” of disorderly con

duct. * * * What is reasonable must always depend

upon the particular case and therefore must be left

to determination on the facts and circumstances of

each situation as it arises. 111. Stat. Ann. ch. 38,

§ 26-1, Committee Comments (Smith-Hurd, 1964).

The entire business of the criminal process is concerned

with an after-the-fact analysis of allegedly “unreasonable”

conduct. If it were possible to define the term, one statute

would either clearly prohibit or clearly permit every con

ceivable course of conduct, trials would be a thing of the

past, and the criminal code system an anachronism of the

times.

With respect to use of the term “ alarm” in the Disorder

ly Conduct statute, its natural meaning is revealed in the

synonymns “ fright, terror, consternation, apprehension,

affright, dread, fear, panic” . Webster’s New Twentieth

Century Dictionary. To “disturb” is “to throw into dis

order; to interfere with; agitate; trouble” . Webster’s

Third New International Dictionary. “Breach of the

peace” “ embraces a great variety of conduct destroying or

menacing public order and tranquility. It includes not

only violent acts but acts and words likely to produce

violence in others”. Cantwell v. State of Connecticut, 310

U.S. 296, 308 (1940). While Edwards v. South Carolina,

372 U.S. 229 (1963), and Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536

(1965) , both involved the invalidation of common-law

breach of the peace offenses, they are distinguishable be

cause there the Supreme Court was vitiating the effect

of statutes aimed and employed for the purpose of

punishing peaceful expression of unpopular views. People

v. Turner, 265 N.Y.S. 2d 841, 856 (Sup. Ct. 1965), affm’d

17 N.Y. 2d 829, 218 N.E. 2d 316 (1966), cert. den. 386

U.S. 773 (1967). Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131

(1966) substantiates this distinction, in that while the

Louisiana “breach of the peace” provision, like Illinois’

use of that term in its Disorderly Conduct statute, was

not given statutory meaning, nevertheless the Court would

have affirmed the conviction but for the fact that it con

sidered the defendants’ “ silent and reproachful presence”

in a segregated library to be first amendment conduct;

at no time did the Brown majority indulge in a “vague

ness” discussion. Id. at 141-42. The situation in Edwards

and Cox, therefore, does not portend the invalidation of

all statutes which employ the term “breach of the peace” .

Those cases embraced a factual lay-out which is too far

afield from the facts in the instant case, where a precisely-

drafted provision was applied by the trial court to con

duct that is clearly outside the protections of the first

amendment. “ The present construction of the Illinois dis

orderly conduct statute is to be contrasted with the fatally

broad construction accorded by the Louisiana Supreme

Court to that State’s breach of the peace statute in Cox

v. Louisiana. . . .” United States v. Woodard, 376 F. 2d

136, 145 (7th Cir. 1967) (concurring opinion).

All words are docile to a certain extent: “ But few words

possess the precision of mathematical symbols, most stat

utes must deal with untold and unforseen variations in

factual situations, and the practical necessities of dis

charging the business of government inevitably limit the

specificity with which legislators can spell out prohibi

tions.” Boyce Motor Lines, Inc. v. United States, 342

U.S. 337, 340 (1952). The Constitution does not ask the

impossible. United States v. Petrillo, 332 U.S. 1, 7-8

(1947). The Seventh Circuit, in United States v. Wood

ard, 376 F. 2d 136, 141-42 (7th Cir. 1967), found

no vagueness in the statutory language of the Dis

orderly Conduct provision: “ In short, we think the Illi

nois statute, ‘when measured by common understanding

and practices’, United States v. Petrillo, supra, provided

84

the defendants with adequate warning that their conduct

was prohibited.” The Woodard court also noted that the

terms “alarm or disturb” actually qualify the broader

meaning of “breach of the peace.” Ibid. In sustaining, as

against a vagueness challenge, New Jersey’s Disorderly

Persons Act, which provides that a disorderly person is

“ any person who by noisy or disorderly conduct disturbs

or interferes with the quiet or good order of any place

of assembly, public or private, including schools, churches,

libraries and reading rooms . . .”, the State’s Supreme

Court stated:

[The] defendant says the statute is void for vague

ness because it does not spell out the degree of

noise or the details of a disorder which will offend.

Of course, the statute does not do so in specific terms,

and it may be doubted that the ingenuity of man

could meet that demand if the Constitution made it.

But the Constitution does not insist upon the impos

sible. It asks only what the subject will reasonably

permit, and hence if there is a public interest in need

of protection, due process does not stand in the way

merely because the subject defies minute prescription.

State v. Smith, 46 N.J. 510, 518, 218 A. 2d 147, 151

(1966), cert. den. 385 U.S. 838 (1967).

Regarding defendant’s vagueness challenge to the “ re

sists or obstructs” language found in the Illinois Resisting

Arrest statute, the use of those terms has been specifically

upheld in Landry v. Daley, No. 67 C 1863 (N.D. 111., filed

March 4, 1968). Nothing need be added to what was said

there:

This statute is designed to deter a person from re

sisting or interfering with the acts of law enforce

ment officials, simply on the basis of the person’s own

conclusion as to the impropriety of the act. It thus

furthers the legitimate state interest in protecting

peace officers, preventing frustration of the valid en

35

forcement of the law, and promoting orderly and

peaceful resolution of disputes. * * * “Resisting” or

“ resistance” means “withstanding the force or effect

of” or the “ exertion of one self to counteract or de

feat” . “ Obstruct” means “ to be or come in the way

of” . These terms are alike in that they imply some

physical act or exertion. Given a reasonable and

natural construction, these terms do not proscribe

mere argument with a policeman about the validity

of an arrest or other police action, but proscribe only

some physical act which imposes an obstacle which

may impede, hinder, interrupt, prevent or delay the

performance of the officers’ duties, such as going limp,

forcefully resisting arrest or physically aiding a third

party to avoid arrest, (pp. 40-42 of opinion. Emphasis

supplied).

During the trial of this cause below, defendant asserted

that the Resisting Arrest statute, as well as § 7-7 of the

Criminal Code (“A person is not authorized to use force

to resist an arrest which he knows is being made either

by a peace officer or by a private person summoned and

directed by a peace officer to make the arrest, even if he

believes that the arrest is unlawful and the arrest in fact

is unlawful.” ), were not intended to prohibit passive re

sistance (Rec. 557-58; Abst. 1.54-55), because they had been

drafted solely to overrule People v. Scalesi, 324 111. 131,

154 N.E. 715 (1926), a case involving active resistance

which the court there held permissible when the arrest was

illegal. Defendant toys with words. If, as stated by Judge

Will in the Landry case, one of the purposes of the Resist

ing Arrest statute is to prevent frustration of the valid

enforcement of the law, the potential for frustration is as

much aided by one’s going limp as by unsuccessful affirm

ative defiance. In both instances, more police officers,

more time, and more exertion are required to effectuate

the arrests, as contrasted to the typical situation where the

36

arrestee voluntarily surrenders his person to station-house

custody. The hazard of violence is equally present in the

one as in the other: “ For the policeman, this form of con

duct [going limp] generates physical labor, hard and, in

his view, unnecessary. When a citizen makes a policeman

sweat to take him into custody, he has created the situa

tion most apt to lead to police indignation and, anger,”

Skolniek, Justice Without Trial 88 (1966). In sustaining Il

linois’ Resisting Arrest statute, the Federal District Court

in Landry did not hesitate to say it embraced “going limp” .

P. 42 of opinion. The court in People v. Knight, 228 N.Y.S.

2d 981, 987-88 (N.Y. City Magistrates Ct. 1962), reached

the same conclusion, because the “arrested party has a

duty to submit to a lawful and proper arrest.” In Re Ba

con, 240 Cal. App. 2d 34 (1966), and People v. Crayton,

284 N.Y.S. 2d 672 (Supreme Ct. 1967) similarly consider

“going limp” to be proscribed under a general “ resisting”

category.

Even If The Disorderly Conduct Statute Could Not Be

Said To Embrace Adequate Due Process Standards On

Its Face, The Subject Matter Being Regulated Necessarily

Requires A Scheme Of Law Administration Involving The

Exercise Of Ad Hoc Judgment By The Police, And Be

cause Defendant Was Apprised Of The Illegality Of His

Conduct, Prior To His Arrest, He Thus Received Fair

Warning That The Conduct Was Prohibited And There

fore May Not Now Assert A Denial Of The Right To Due

Process Of Law.

Even if the defendant were correct in his asserted vague

ness attack upon the Disorderly Conduct provision, a good

argument can be made that the subject matter of the

statute, being so broad and diverse as it is, necessarily

anticipates a certain degree of on-the-spot judgment by

police officers. Therefore, because the record (Bee. 288,

337, 357, 414, and 459-60; Abst. 43, 53, 70, 101-103, and

120) shows without rebuttal the testimony of five prosecu

tion witnesses that the defendant was warned of an

impending arrest if he persisted in sitting in the street

intersection, defendant was given an authoritative and

official construction of the statute by the police such that

he was put on notice, before arrest, that his conduct

was illegal. The United States Supreme Court indirectly

endorsed this ad hoc judgment approach in Cox v. Loui

siana, 379 U.S. 559, 568-70 (1965) where it noted that

use of the language “near” in the Louisiana State statute

prohibiting demonstrations “near” a courthouse, axio-

matically foresaw a degree of on-the-spot administrative

interpretation. As additional authority, Professor An

thony G. Amsterdam has concluded from his research

of United States Supreme Court cases that “ where the

subject matter of regulation is such as to make unfeas

ible modes of law administration other than those which

involve ad hoc judgments, considerable pressures are

created in favor of permitting an ad hoc judgment

scheme.” Amsterdam, Void-For-Vagueness Doctrine in the

Supreme Court, 109 U. Pa. L. B. 67, 95 (1960) Professor

Alfred Kamin of Loyola University has posited the argu

ment in necessity terms: “ Granting that the first amend

ment may limit the exercise of municipal discretion in

banning beforehand public gatherings . . ., some room must

be left for administrative discretion of police on the scene

of an active meeting or demonstration.” Kamin, Besi-

dential Picketing and the First Amendment, 61 Nw. U. L.

B. 177, 220 (1966).

38

II., V-

THE DISORDERLY CONDUCT AND RESISTING AR

REST COMPLAINTS AND JURY INSTRUCTIONS

WERE NOT ERROR SINCE THEY ADEQUATELY

INSTRUCTED THE DEFENDANT AND THE JURY

OF THE NATURE AND THE ELEMENTS OF THE

OFFENSES CHARGED AND IN NO WAY PREJU

DICED PUS DEFENSE,

As was discussed in the above arguments, neither the

disorderly conduct nor the resisting arrest statute are

so vague that a reasonable man of ordinary intelligence

cannot know whether a particular act, in the context of the

situation, is prohibited. Neither are the statutes over

broad in the sense that they have allowed a pattern of en

forcement or, in the absence of a pattern of enforcement,

that the natural and reasonable construction of the lan

guage of the statutes would allow punishment for the

exercise of constitutionally protected rights.

THE COMPLAINTS

Since the words of these statutes are not vague and

reasonably put one on notice of what is unlawful, it is

axiomatic that complaints phrased in the words of these

statutes along with the name of the offense charged, the

citation to the applicable statute, the date and place of the

alleged offense, and the name of the accused sufficiently

specify the offenses charged. This conforms to the statu

tory standard:

A charge shall be in Avriting and allege the com

mission of an offense by :

(1) Stating the name of the offense;

39

(2) Citing the statutory provision alleged to have

been violated;

(3) Setting forth the nature and elements of the of

fense charged;

(4) Stating the time and place of the offense as defi

nitely as can be done; and

(5) Stating the name of the accused, if known, and

if not known, designate the accused by any name

or description by which he can be identified with

reasonable certainty. 111. Rev. Stat. eh. 38, § 111-

3 (a), (1967).

Since criminal procedure is not a game to be played

between the accused and the state, the accused who feels

inadequately informed of the offense charged may move

the court to order a bill of particulars to be provided:

When . . . [a] complaint charges an offense in ac

cordance with the provisions of Section 11-3 of this

code but fails to specify the particulars of the offense

sufficiently to enable the defendant to prepare his

defense the court may, on written motion of the de

fendant, require the State’s Attorney to furnish the

defendant with a Bill of Particulars containing such

particulars as may be necessary for the preparation

of the defense. At the trial of the cause the State’s

evidence shall be confined to the particulars of the

bill. 111. Rev. Stat, ch. 38, § 111-6, (1967)

The defendant objected to the sufficiency of the com

plaint on its specificity, the People suggested that the

defendant’s remedy was a bill of particulars and the court

so ruled. (Rec. 228, 231, 234; Abst, 25-28, 30) The defend

ant rejected this because, since he assumed the complaint

to be insufficient on its face, he did not wish to lend the

complaint any sufficiency. (Rec. 235; Abst. 30)

Only last fall, this court was presented with a similar

argument upon remarkably similar facts. In City of Chi

40

cago v. Joyce, 38 ILL 2d 368; 232 N.E. 2d 289, (1967),

the defendant was engaged in a civil rights protest at Chi

cago’s City Hall. To protest the alleged arrest of some of

her fellow demonstrators, the defendant sat down in the

middle of the sidewalk (only a few yards from the inter

section where Mr. Baby sat or lay) interlocked her arms

and legs with some of her fellow demonstrators and

began to sing loudly. She and the other demonstrators

were warned to cease their loud singing and blocking the

sidewalk or they would be arrested. After not complying

with the orders of the police, the demonstrators were ar

rested, and Miss Joyce went limp whereupon she had to be

carried to a police van. 38 111. 2d at 370-371.

After her conviction, Miss Joyce appealed to this court

alleging “ that she was deprived of her right of free

speech, that the applicable ordinance is void for vague

ness, that the complaints were not sufficiently specific . . .”

Id. at 369. The Court rejected all of her contentions in

affirming the conviction:

[T]he defendant’s conduct in sitting on the side

walk, blocking the entrance to the city hall and ob

structing pedestrian traffic has no connection with

the constitutional protections [free speech] she seeks

to invoke.

Defendant next insists that the ordinances she was

found to have violated are unconstitutionally vague.

It does not appear that the objection was raised or

passed upon in the trial court, and there is thus no

ruling on review, [citing cases] We have neverthe

less considered defendant’s argument and find it to be

without merit.

The contention that the complaints are not suffi

ciently specific must also be rejected. The one alleges,

inter alia, that defendant committed disorderly conduct

by making or aiding in making an improper noise or

41

disturbance, and the other charges that she willfully

and unnecessarily hindered, obstructed and delayed

persons lawfully traveling along the sidewalk. The

date and place are specified in each. The appellant

nowhere explains how she was misled or inadequately

informed of the charges against her, and it is plain

that both she and her counsel were well aware of the

particular conduct which brought about the arrest. The

complaints adequately advised the defendant of the

nature of the offenses and were sufficient to enable her

to prepare a defense. I f defendant felt that a more

detailed statement was necessary a motion to that

effect could have been made. This she did not do.

Under such circumstances there is no basis for claim

ing on review that the complaint is not specific enough.

Id. at 371-372; emphasis added.

Here, as in Joyce, the complaints are sufficient on their

face. (See Appendix A) -Here, the defendant was invited

to request a bill of particulars but did not do so. Con

trary to the situation in Joyce, defense counsel has made

a good record of his objections regarding the defendant’s

supposed lack of knowledge of the charges against him

but this is mere pretense. The record is rife with testi

mony, and even admissions by the defendant (e.g., Bee.

825, 837, 849, 850; Abst, 258-259, 261-262), that he did, in

fact, sit down in the intersection and upon arrest went

limp and was carried away. A cursory reading of the

record will demonstrate that, rather than cast doubt upon

the guilt of the defendant, defense strategy was to confuse

the jury with testimony regarding alleged racial segrega

tion in Chicago schools, alleged police brutality, and the

defendant’s good reputation. Nowhere was it contended

that the defendant did not commit or did not intend to

commit the offenses for which he was being prosecuted.

The defendant argues that he does not even now know

whether he was convicted of disorderly conduct for making

42

the speech that he made shortly before (and one half block

away from where) he sat down in the intersection, al

though the complaint clearly states that the situs of the

offense was the intersection. The record demonstrates

that this is pure sophistry.

The defendant complains that he might be subjected to

double jeopardy for the offenses for which he is here

convicted. What the defendant is doing here is admitting

that he committed other offenses of disorderly conduct

and resisting arrest at Randolph and La Salle Streets

on June 28, 1965, and then attempting to foreclose other

prosecutions (or this prosecution) by his failure to secure

a bill of particulars. Surely this court will not allow the

defendant to overturn his convictions for two offenses by

admitting that he committed other unnamed offenses at the

time and place for which he may be prosecuted.

The court in City of Chicago v. Lambert, 47 111. App.

2d 151; 197 N.E. 2d 448 (1964), was faced with similar

arguments regarding the sufficiency of complaints charging

criminal defamation under the State statute and disorderly

conduct under Chicago ordinance. The court said:

[W]e believe the entire record before us would pre

vent any subsequent prosecution of these defendants

for the same offenses. We believe that defendants’

rights to a fair trial have not been violated. In Smith

v. United States, 360 U.S. 1, at page 9, 79 S. Ct.

991, at page 996, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1041 the court said: ‘ [The

Supreme Court of the United States] has, in recent

years, upheld many convictions in the face of ques

tions concerning the sufficiency of the charging papers.

Convictions are no longer reversed because of minor

and technical deficiencies which did not prejudice the

accused. * * * This has been a salutary development

in the criminal law.’ Niceties and strictness of plead

ings are supported only when defendants would be

43

otherwise surprised on trial or unable to meet the

charges or prepare their defenses. People v. Wood

ruff, 9 111. 2d. 429, 137 N.E. 2d 809 (1957); People

v. Nastario, 30 111. 2d 51, 195 N.E. 2d 144 (1963).

The cases cited by the defendant in support of his

proposition that the complaints are not sufficiently specific

state the past Illinois law applicable to the facts of those

cases but all are distinguishable from the instant case.

It is quite likely, for instance, that the statute under which

the defendant in People v. Brown, 336 111. 257, 168 N.E.

289 (1929), was convicted would today be found void for

vagueness. In that case the court said that:

The general rule is that it is sufficient to state the

offense in the language of the statute, but this rule ap

plies only where the statute sufficiently defines the

crime. Where the statute creating the offense does

not describe the act or acts which compose it, they

must be specifically averred in the indictment or in

formation. [citing cases] 336 111. at 258-259.

None of these cases deal with violations of the disor

derly conduct or resisting arrest statutes. People v. Col

lins, 35 111. App. 2d 228; 182 N.E. 2d 387 (1962), was a

proposecution for the performance of lewd and indecent

acts and the complaint failed to allege an essential portion

of the statute in its language. People v. Brown, supra,

was a prosecution for practicing medicine without a li

cense. People v. Peters, 10 111. 2d 577; 414 N.E. 2d 9

(1957), was a prosecution for the unauthorized and fraud

ulent practice of law. People v. Williams, 30 111. 2d 125;

196 N.E. 2d 483 (1963), was a prosecution for an at

tempted burglary in which the complaint failed to dis

close the address of the place which the accused allegedly

attempted to burglarize. People v. Flynn, 375 111. 366;

44

31 N.E. 2d 591 (1941), was the prosecution of the Mayor

of Champaign for non-feasance in office.

As the first argument in this brief has demonstrated,

the Disorderly Conduct statute is worded in such a way as

to proscribe only actions which tend to disturb others and

provoke disruptions of public order when such actions are

unreasonable in the context of the particular situation.

See 38 S.H.A. § 26-l(a), Committee Comments (1967). At

least one higher court has found this purpose and method

of legislation to pass the constitutional prohibitions against

vague legislation. United States v. Woodard, 376 F. 2d

136 (7th Cir. 1967) Because of the subject matter of the

offense of disorderly conduct, law governing the specifi

city of complaints charging other offenses should not ipso

facto determine the specificity essential to a disorderly

conduct complaint.

THE INSTRUCTIONS

The defendant, at page 43 of his brief, states the propo

sition that “ [i]f the complaints in the instant case are

defective and constitutionally void, in that they wholly

fail to inform the defendant of the nature and elements

of the charge(s) against him a fortiori the instructions

given to the jury are equally defective and constitution

ally void,” because the instructions are worded in the

language of the complaints. This is true and so is the

corollary that if the complaints adequately informed the

defendant of the nature and the elements of the offenses

charged a fortiori the instructions given to the jury are

equally adequate. Since the above argument on the suf

ficiency of the complaints demonstrates their adequacy, the

instructions are equally adequate. It need hardly be men

tioned that, since the complaints and, in turn, the instruc

tions were worded in the language of the statutes, the

45

statutes must first pass constitutional muster in order to

validate the instructions, c.f. Terminiello v. City of Chi

cago, 337 U.S. 1; 69 S. Ct. 894 (1949).

The defendant argues that the instructions here were

inadequate and therefore warrant reversal on the case

of People v. Davis [74 111. App. 2d 450; 221 N.E. 2d 63

(1966)]. The People have no dispute with the holding of

Davis but find it wholly inapposite to the instant case.

Davis was a prosecution for the offense of attempt to com

mit robbery. 111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38, §§ 8-4, 18-1, (1967).

The complaint or indictment was evidently sound but the

jury was instructed:

The jury are instructed that a person commits an

attempt when, with intent to commit a specific offense,

he does any act which constitutes a substantial step

toward the commission of that offense. 74 111. App.

2d at 452; court’s emphasis.

Nowhere in any of the jury instructions was the word

robbery mentioned or in any way was the jury instructed

as to what the accused had allegedly attempted. This case

has no application to the instant ease where the complaints

are adequate and the instructions are in the language

of the statutes and the complaints.

In giving the State’s instruction number 17, the court

adopted the rule of People v. Knight, 35 Misc. 2d 218;