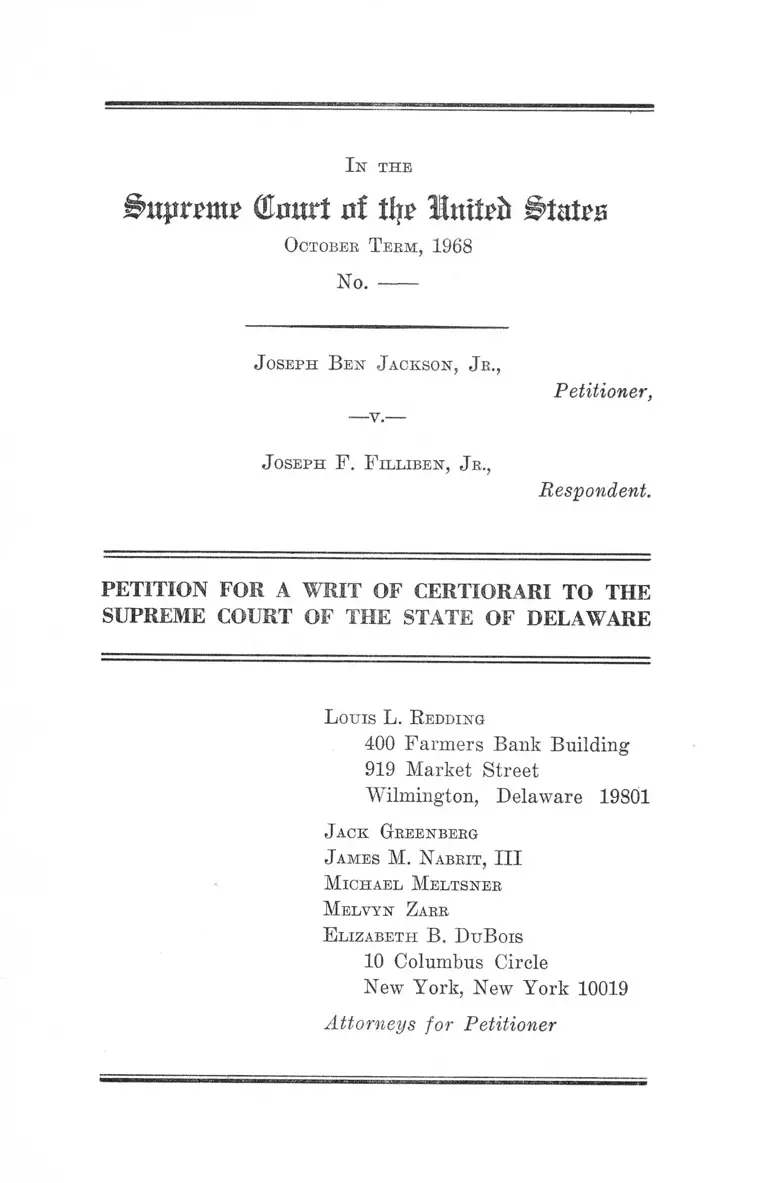

Jackson v. Filliben Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of Delaware

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Filliben Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of Delaware, 1968. a9c990f8-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c617eebb-426d-48ba-aba3-d3dbd1917655/jackson-v-filliben-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-the-state-of-delaware. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

I h t p r m ? G Im trt n f tty? I n t t p f t B M ? b

O ctober T e e m , 1968

No.

J o se ph B e n J a ck so n , J r .,

— v.—

Petitioner,

J o se ph F. F il l ib e n , J r .,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE

Louis L. R edding

400 Farmers Bank Building

919 Market Street

Wilmington, Delaware 19801

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N a b eit , III

M ic h a e l M e l t sn e r

M elvyn Zarr

E l iz a b e t h B . D u B ois

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Citation to Opinion Below ..... ................... ..... ........... . 1

Jurisdiction ........................ 1

Questions Presented................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved.... . 2

Statement ............................. 2

Reasons for Granting the Writ—

Introduction............................................................ 7

PAGE

I. Petitioner Cannot Be Held Liable in Defama

tion on the Basis of a Statement Alleging That

Respondent Police Sergeant Had Violated

Rights Protected Under the Constitution and

Statutes of the United States, Published to Au

thorities Responsible for Investigating and Pre

venting Such Law Violations ............................ 8

II. Petitioner Cannot Be Held Liable in Defamation

on the Basis of a Report to Proper Authorities

Regarding Alleged Violation by a Police Ser

geant of Rights Protected Under the Constitu

tion and Statutes of the United States Where

the Record Shows No Malice Under the Stan

dards Laid Down in New York Times Co. v.

Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) ............................ 11

A p p e n d ix A —

Opinion Below......................................................... la

A ppe n d ix B —

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved 4a

A p p e n d ix C—

Letter from Petitioner to the Police Commissioner 8a

11

T able op Cases

page

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941) ...... .......... 10

Burg v. Boas, 231 F.2d 788 (9th Cir. 1956) ............ . 10

Cohen v. Beneficial Loan Corp., 337 U.S. 541 (1949) .... 6

Construction Laborers v. Curry, 371 U.S. 542 (1963) .... 7

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) ................. 7

Foltz v. Moore McCormack Lines, Inc., 189 F.2d 537

(2nd Cir.), cert, denied 342 U.S. 871 (1951) .......... 9

Gabriel v. McMullin, 127 Iowa 426, 103 N.W. 355 (1905) 10

Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64 (1964) ..................... 12

Gilligan v. King, 48 Misc. 2d 212, 264 N.Y. Supp.2d

309 (1965) ................................. ...................... ......... 12

Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966) ................. 7

Henry v. Collins, 380 U.S. 356 (1965) ........................ 11

Ilott v. Yarbrough, 112 Tex. 179, 245 S.W. 676 (1922) 10

In re Quarles, 158 U.S. 532 (1895) ............................9,10

Mercantile National Bank v. Langdeau, 371 U.S. 555

(1963) ......................................................................... 7

Mills v. Alabama, 384 U.S. 214 (1966) ........................ 7

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) ........ ............ 7

New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) ....3, 5, 6, 8,

10,11,12,13,14

Oswalt v. State-Record Co., 158 S.E.2d 204 (S.C.

S.Ct. 1967) 12

I l l

PAGE

Pape v. Time, 354 F.2d 558 (7th Cir. 1965) ................. 12

Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968) 14

Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967) ........................ 9,10

Pope v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 345 U.S. 379 (1953) 6

Rosenblatt v. Baer, 383 U.S. 75 (1966) ........................ 11

St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727 (1968) .............. 11

State of North Carolina v. Carr, 386 F.2d 129 (4th

Cir. 1967) .............................................. 9

Suchomel v. Suburban Life Newspapers, Inc., 84 111.

App. 2d 239, 228 N.E.2d 172 (1967) ........................ 12

Sullivan v. Crisona, 283 N.Y. Supp. 2d 62 (1967) ___ 10

Swaaley v. United States, 376 F.2d 857 (U.S. Ct. Claims

1967) ........................................................................... 12

Thomas v. Loney, 134 U.S. 372 (1890) ........................ 9

Touhy v. Ragen, 340 U.S. 462 (1950) ......................... 9

U.S. v. Moser, 4 Wash. C.C. 726 ................................... 10

Vogel v. Cruaz, 110 U.S. 311 (1884) ............................9,10

Washington Post Co. v. Keogh, 365 F.2d 965 (D.C.

Cir. 1966) ........................................ 7

Wells v. Toogood, 165 Mich. 677, 131 N.W. 124 (1911) 10

White v. Nicholls, 3 How. 266, 44 U.S. 266 (1845) ...... 9

Worthington v. Scribner, 109 Mass. 487 ..................... 10

18 U.S.C. §§241, 242 ..

28 U.S.C. §1257 ........

42 U.S.C. §§1983, 1985

S tatutes

2.9

1,6

2.9

IV

Ot h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Annot., 140 A.L.E. 1466 (1942) ................................... 12

Bertelsman, Libel and Public Men, 52 A.B.A.J. 657

(1966) ......................................................................... 12

Casenote, 51 Colum. L.J. 244 (1951) ............................ 12

1 Harper S James, Torts §§5.22, 5.23 (1956) .............. 10

Noel, Defamation of Public Officers and Candidates,

49 Colum. L.J. 875 (1949) ....................................... 13

Note, 78 Yale Law Journal 156 (1968) ...................... . 8

Prosser, Torts §109 (1964) ........................................ . 10

Prosser, Torts §110 (1964) ..................................... ..... 12

Restatement, Torts §§585, 586, 587 (1938) ................. 10

Restatement, Torts §598 (1938) ................................... 12

PAGE

I n T H E

u p r m e (Emtrt n f tl|p I m tP ii B u U b

O ctober T e e m , 1968

No. -----

J o se ph B e n J a ck so n , J b .,

Petitioner,

J o se ph F . F il l ib e n , J b .,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of the State of Dela

ware entered on October 28, 1968.

Citation to Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of the State of Dela

ware is reported at 247 A.2d 913, and is set out in Appendix

A hereto, pp. la-3a, infra.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of the State of

Delaware was entered on October 28, 1968. Jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1257(3), petitioner

having asserted below and here the deprivation of rights

secured by the Constitution and statutes of the United

States.

2

Questions Presented

Petitioner made a report to the F.B.I. and the Police

Commissioner (Respondent police sergeant’s highest supe

rior) that Respondent had committed acts constituting, in

Petitioner’s opinion, police brutality, thus depriving him

of his rights under the Constitution and laws of the United

States. Solely on the basis of this report, Respondent sued

Petitioner for defamation.

1. Is the report absolutely privileged under the Consti

tution and laws of the United States?

2. Is the report privileged, absent any showing of malice,

under the Constitution and laws of the United States?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the First, Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves 18 U.S.C. §§241, 242, and 42

U.S.C. §§1983, 1985, which are fully set out in Appendix B

at pp. 4a-6a, infra.

Statement

Respondent, Joseph F. Filliben, Jr., filed a complaint in

the Superior Court of the State of Delaware on July 26,

1966, alleging that Petitioner, Joseph Ben Jackson, Jr.,

made false charges of police brutality against Respondent

to the U.S. Attorney at Wilmington, Delaware. (Com

plaint, para. 7). Petitioner moved in his answer, Sept. 16,

for a dismissal of the complaint on the ground that any

statements he may have made were privileged. He sub

sequently moved for judgment on the pleadings on the

grounds that he had an absolute privilege to report viola

3

tions of federal law to the appropriate federal official; and,

alternatively, that malice could not be shown and there

fore, under the doctrine of New York Times v. Sullivan,

376 U.S. 254 (1964), he could not be subjected to liability

for his statement regarding Respondent, This motion was

denied by order, without opinion, May 18, 1967.

At trial Respondent introduced evidence that Petitioner

had sent a letter (P. Ex. #1 ; App. C, pp. 8a-13a, infra)

to the Police Commissioner, Respondent’s highest supe

rior, and that a copy of this letter had been received by

the F.B.I. The letter states that in accordance with the

Commissioner’s instructions, petitioner was submitting the

letter “as an official complaint of abuse by Police.” (App.

p. 8a, infra).

The letter describes incidents which arose out of peti

tioner’s arrest by Respondent Filliben, a police sergeant,

the night of December 2, 1965. Briefly it states that Peti

tioner had been driving to work the night of December 2

when he was stopped by Sergeant Filliben who ordered

him out of the car, grabbed him when he did get out and

held him while another officer handcuffed his hands behind

his back, “causing unbearable pain.” “I was then thrown

to the ground. I tried to get up several times but each

time I was knocked back down. Sergeant Filliben then told

one of the officers to hold me down and he immediately

complied by dropping down upon me with his knee.” (App.

pp. 9a-10a, infra). While on the ground Petitioner asked

the officer holding him to loosen the handcuffs because they

were hurting him, but was told to shut up. Subsequently,

the letter goes on, the patrol wagon came, and when Peti

tioner objected to getting into it Sergeant Filliben

“grabbed me and slammed me back down on the ground.”

(App. p. 10a, infra). Petitioner again asked to have his

handcuffs loosened. He was put in the wagon and taken,

eventually, to the station.

4

All during the ride I was begging and pleading for

relief of the pain on my wrist. . . . After I was taken

into the station the officer who had told me fin the

patrol wagon] that he didn’t have a key to fit the

handcuffs on my wrists, selected one from a bunch of

keys in his possession and caused me to bend over

with my head almost between my knees. He then un

locked the handcuffs. My wrists were terribly bruised.

. . . (App. pp. lOa-lla, infra).

The letter goes on to describe repeated demands by Ser

geant Filliben as to whether Petitioner was going to have

the case continued, and to relate a conversation containing

the only mention of “police brutality” in the letter.

[At the station] I started to make a third call to

borrow money to get my automobile that was left at

the scene with the motor running and lights on because

the Sgt. told me that it would be impounded but was

told to hang up. Sgt. Filliben then asked me again if I

was going to have the case continued? I said to him “I

really don’t know. I have often read and heard of police

brutality but had no idea that I would ever experience

it.” Sgt. Filliben then said, “you’re lucky. Ten years

ago I would have black jacked you.” . . . I said, “With

hand cuffs on!” He said, “That’s right boy you’re

lucky.” . . .

. . . The next morning while sitting on a bench in

the hall of the Public Building reading a newspaper

at about 8:40 A.M., Sgt. Filliben approached me and

said, “Ben are you going to have this case continued!”

I said nothing. He repeated the question and I did

not answer him. He then said, “All right boy, I just

gave you your last chance” as though to threaten me.

(App. pp. lla-12a, infra).

5

At trial Respondent introduced evidence which, consid

ered most favorably for Respondent, basically differed

from the account given in Petitioner’s letter only in alleg

ing certain provocative acts by Petitioner at the time of

his arrest, and in alleging that Petitioner had fallen rather

than been thrown to the ground.1

At the close of Respondent’s case, which included testi

mony by Petitioner, the latter moved for a directed ver

dict which was granted on the ground that Respondent

had failed to prove that the charge of police brutality was

made to the U.S. Attorney, as alleged in the complaint.

On appeal to the Supreme Court of the State of Dela

ware, Petitioner argued that the judgment below should be

affirmed on the ground, among others, that Petitioner could

not be held liable in defamation on the evidence presented

consistently with the First Amendment and the doctrine

announced in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S.

254 (1964). The Court found that the evidence showed a

publication of the charge of “police brutality” to the Police

Commissioner, Respondent’s highest superior, and to the

F.B.I., and therefore, since the variance between the com

plaint and the pleadings consisted solely in the identity

1 Respondent’s evidence indicated that while driving from work

in uniform hut in his own ear he had noticed Petitioner speeding,

and had pursued and stopped Petitioner with the aid of other offi

cers. Petitioner had initially refused to get out of his car, and had

eventually emerged cursing and waving his arms about, at which

point he was grabbed and handcuffed. Respondent’s evidence indi

cated that Petitioner had then fallen to the ground and that, be

cause of his efforts to kick, Respondent ordered an officer to hold

him down. Petitioner was later carried to the wagon, dropped to

the ground when he kicked, and eventually placed in it. (See Tr.

12, 14, 15, 19, 51, 52, 54.)

The evidence also indicated that Respondent Filliben subse

quently charged Petitioner with speeding, failing to stop at the

command of a police officer, disorderly conduct and resisting arrest,

and that after a hearing on all of these charges, Petitioner was

convicted only of disorderly conduct (Tr. 40-44). Respondent’s

witnesses never denied that Sergeant Filliben had in fact grabbed

6

of the persons to whom the charges were made, direction

of the verdict on this basis was unjustified. The Court

further ruled that the charge of police brutality was not

fatally vague, and finally that, assuming Respondent was

a public official within the meaning of Times v. Sullivan,

supra, the issue of malice was a matter for the jury.

Petitioner seeks review of this judgment on the basis

that it is final within the meaning of 28 U.S.C. §1257. This

Court had often said that the requirements of finality must

be given a practical, not a technical construction. See,

e.g., Cohen v. Beneficial Loan Corp., 337 U.S. 541 (1949);

Pope v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 345 U.S. 379 (1953).

It is Petitioner’s contention, developed more fully, infra,

pp. 8-14, that the allegedly defamatory utterance was

protected under the Constitution and statutes of the United

States, and particularly the First Amendment, and there

fore that there is no issue for a jury in this case. The

considerations of judicial economy central to 28 U.S.C.

§1257 dictate that this case be finally disposed of now,

rather than remanded for a new trial which would probably

result in a verdict for Respondent,2 another appeal, and

another Petition for Certiorari. Further, denying Petitioner

and held Petitioner while another officer handcuffed him or that

Respondent had ordered another officer to hold Petitioner, whose

hands were handcuffed behind his back, on the ground. Nor did

Respondent’s witnesses deny any of the other significant elements

of the story outlined in Petitioner’s letter, such as Petitioner’s com

plaints regarding the tight handcuffs, the fact that these com

plaints were ignored, and Respondent’s various intimidating and

demeaning comments. Most significantly, Respondent never denied

that the conversation in which Peitioner mentioned “police bru

tality”—and it is this reported conversation that was the basis of

the libel action—took place as described in the letter.

2 At any new trial Petitioner would have the heavy burden,

under the law and particularly the test of malice established by the

court below, of persuading a jury of the complete truth of the

entire account of the incident outlined in the letter, in the face of

testimony by four police officers, supported by one private citizen,

in their refutation of a charge of police brutality.

7

relief now will finally deny him the essential right not to be

forced to submit, in order to vindicate his right to speak, to

further lengthy and expensive litigation with its inherent

dangers of coerced settlement and its inevitable chill on

First Amendment rights. See, e.g., Mills v. Alabama, 384 U.S.

214, 221 (1966) (concurring opinion); Dombrowski v. Pfil

ter, 380 U.S. 479 (1965); and see Construction Laborers v.

Curry, 371 U.S. 542 (1963); Mercantile National Bank v.

Lcmgdeau, 371 U.S. 555 (1963). Cf. Washington Post Co.

v. Keogh, 365 F.2d 965, 968 (D.C. Cir. 1966); Greenwood

v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808, 829 (1966) (dictum) (dealing

with 28 U.S.C. §2283).3

Reasons for Granting the Writ

Introduction

This case involves the right of a private citizen to report

an alleged abuse by a police sergeant of rights protected

by the Constitution and statutes of the United States to

that officer’s highest superior and to the F.B.I., authorities

charged with responsibility for investigating and prevent

ing such law violations. On a record which, considered

most favorably for Respondent, fails to negate Petitioner’s

honest belief in the published charge of “police brutality,”

the Court below found that Petitioner could be held liable

in defamation. In numerous cases concerning the exclu

sion of illegally obtained evidence this Court has pointed

to the absence of significant deterrents to police abuse and

has recognized the extraordinary difficulty that citizens

have in proving a case of such abuse. See, e.g., Miranda

v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). To permit the police to

3 The mere fact that it is conceivable that a new trial in this case

cotild result in a judgment for Petitioner is not conclusive. See,

e.g., Mills v. Alabama, supra, 384 U.S. at 217, 221, 222 and n. 1;

cf. Dombrowski v. Pfister, supra, 380 U.S. at 487; Mercantile Na

tional Bank v. Langdeau, supra, 371 U.S. at 573.

8

use defamation actions to punish any citizen who dares to

complain to authorities whose responsibility it is to pre

vent such abuse is intolerable and inconsistent with the

principles recently enunciated in New York Times Co. v.

Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

I.

Petitioner Cannot Be Held Liable in Defamation on

the Basis of a Statement Alleging That Respondent

Police Sergeant Had Violated Rights Protected Under

the Constitution and Statutes of the United States,

Published to Authorities Responsible for Investigating

and Preventing Such Law Violations.

It is Petitioner’s contention that he had an absolute

privilege to report alleged police brutality to the Police

Commissioner, Respondent’s highest superior, and to the

and therefore that there should be no judicial in

quiry in a defamation suit into the truth of his allegation

or into his motives in making it. To subject persons in

Petitioner’s position to defamation suits in which they

must prove to a jury’s satisfaction the truth4 of any re

ports they have made would greatly increase the difficulty

of enforcing the laws governing police conduct, and place

an intolerable burden on First Amendment rights. See,

e.g., Note, 78 Yale L.J. 156, 163, 170 (1968). Moreover,

where publication is only to authorities responsible for

investigating such law violations, the accused has an oppor

tunity to answer the charges in the course of any inves

tigation and, unless the charges are found to be substan

tiated, his reputation should not suffer significantly.

4 In bolding that a finding of malice could be made on this evi

dence the court in effect held that Petitioner could be held liable

unless the allegations contained in his letter were in fact true.

9

An absolute privilege to report law violations to author

ities responsible for investigating and prosecuting such

violations has previouly been recognized by this Court.

See, e.g. In re Quarles, 158 U.S. 532 (1895); Vogel v.

Gruaz, 110 U.S. 311 (1884). But cf. White v. Nicholls, 3

How. 266, 44 U.S. 266 (1845); Foltz v. Moore McCormack

Lines, Inc., 189 F.2d 537 (2nd Cir.), cert, denied, 342 U.S.

871 (1951). Federal law clearly ought to govern any re

ports made to the F.B.I. Cf. Thomas v. Loney, 134 U.S.

372 (1890); Foltz v. Moore McCormack Lines, Inc., supra.* 6

Similarly, federal law ought to govern reports of alleged

violation of federal statutes-—here 18 U.S.C. §§241, 242

and 42 U.S.C. §§1983, 19856—and of the federal constitu

tion—here the right not to be punished without due process

of law—when these reports are made to persons respon

sible for seeing that such violations do not occur. (The

Police Commissioner, as Petitioner’s highest superior, is

in a position to penalize any such law violations by pro

viding for the discipline of the guilty officer.) Obviously

it would be intolerable to allow a State to frustrate the

implementation of federally protected rights by imposing

its own restrictions on the ability of persons to seek redress

for the violation of such rights. Therefore this Court could

find Petitioner’s letter protected by an absolute privilege

simply as a matter of federal lawr.

But in addition, the right to report law violations free

from the fear of defamation suits is, under these circum

stances, of constitutional dimension. In In re Quarles,

supra, this Court held that the right to inform a U.S.

6 Thus the U. S. Attorney in Delaware asserted his right in this

case to refuse to disclose in the State court proceedings any in

formation he had obtained from Petitioner. See Becord in Su

perior Court Nos. 23, 24 and authorities cited, including State of

North Carolina v. Carr, 386 F.2d 129 (4th Cir. 1967). See also

Touhy v. Bagen, 340 U.S. 462 (1950).

6 See generally Pierson v. Bay, 386 U.S. 547 (1967).

10

Marshall of a law violation was a right “secured by the

Constitution of the United States,” 158 U.S. at 537-538;

and see Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252, 277 and n. 21

(1941). And in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S.

254 (1964), this Court looked to the common law of de

famation in fashioning the limits imposed by the First

Amendment on a state’s ability to allow actions for de

famation by public officials. An absolute privilege to

speak free from any fear of liability in defamation has

long been recognized at common law in a variety of cir

cumstances, including judicial and quasi-judicial or ad

ministrative proceedings, and any necessary preliminaries

to such proceedings. See generally P rosser, T orts §109

(1964) ; 1 H arper & J a m es , T orts §§5.22, 5.23 (1956);

R e s t a t e m e n t , T orts §§585, 586, 587 (1938). Cf. Pier

son v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967). And in many jur

isdictions this absolute privilege has been specifically held

to cover informal complaints of law violations made to

police7 or prosecutors. In addition to this Court’s deci

sions in In re Quarles and Vogel v. Gruaz, supra, see, e.g.,

Gabriel v. McMullin, 127 Iowa 426, 103 N.W. 355 (1905);

Worthington v. Scribner, 109 Mass. 487; Wells v. Toogood,

165 Mich. 677, 131 N.W. 124 (1911); U.S, v. Moser, 4

Wash. C.C. 726; Rott v. Yarbrough, 112 Tex. 179, 245

S.W. 676 (1922); Burg v. Boas, 231 F.2d 788 (9th Cir.

1956) (dictum); see generally R e st a t e m e n t , T orts §587

(1938); P rosser, T orts §109 at 800 (1964). This Court

7 The allegation of police brutality would of course, if true, con

stitute a violation not only of federal law but also of state laws,

and it would therefore be appropriate to report such a violation to

the Police Commissioner. But in any event, a report of any law

violation to the Police Commissioner ought be absolutely privileged

as a necessary preliminary to quasi-judicial disciplinary proceed

ings. Cf. Sullivan v. Crisona, 283 N.Y. Supp.2d 62 (1967) (abso

lute privilege covers Bar Association Grievance Committee pro

ceedings) .

11

should grant certiorari to determine whether a balancing

of the interests involved does not, under the First Amend

ment and the principles enunciated in New York Times

Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964), require an absolute

privilege to report law violations to proper authorities.

II.

Petitioner Cannot Be Held Liable in Defamation on

the Basis of a Report to Proper Authorities Regarding

Alleged Violation by a Police Sergeant of Rights Pro

tected Under the Constitution and Statutes of the United

States Where the Record Shows No Malice Under the

Standards Laid Down in New York Times Co. v. Sul

livan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

Whether or not Petitioner’s report is protected by an

absolute privilege, as argued supra, pp. 8-11, it is

at least protected by the qualified privilege outlined in

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

The Court below based its decision on the assumption that

Respondent police sergeant was a public official within

the meaning of Times v. Sullivan, but purported not to

decide that question. However, there should be no doubt

that a defamation suit by a police sergeant, a person with

“substantial responsibility for or control over the conduct

of governmental affairs,” whose qualifications and per

formance are of particular interest to the public (Rosen

blatt v. Baer, 383 U.S. 75, 85, 86 (1966)), on the basis of

a report accusing him of violating rights protected under

the Constitution and laws of the United States, a matter

of enormous and legitimate public interest, should be gov

erned by the principles enunciated in Times v. Sullivan.

See, e.g., St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727 (1968)

(deputy sheriff); Henry v. Collins, 380 U.S. (1965) (chief

12

of police) ; Pape v. Times, 354 F.2d 558 (7th Cir. 1965)

(deputy chief of detectives and police lieutenant) ; Sucho-

mel v. Suburban Life Newspapers, Inc., 84 111. App. 2d 239,

228 N.E.2d 172 (1967) (police sergeant); Gilligan v. King,

48 Misc.2d 212, 264 N.Y. Supp.2d 309 (1965) (police lieu

tenant) ; Oswalt v. Slate-Record Co., 158 S.E.2d 204 (S.C.

S.Ct. 1967) (police officer); see generally Bertelsman, Libel

and Public Men, 52 A.B.A.J. 657, 661, 662 (1966).

Moreover, Petitioner’s report would be protected at

least by a qualified privilege under common law doctrines

of greater importance, and more universally accepted, than

that raised to constitutional dimensions in Times v. Sul

livan. Thus it has long been held that no action in de

famation will lie in the absence of malice for a complaint

to proper authorities regarding the conduct of public

employees. See, e.g., P rosser , T orts §110 (1964); R esta te

m e n t , T orts §598 and comment (c) (1938); Ca sen o te , 51

Colum. L.J. 244 (1951). And the right to report law

violations to police or prosecutors has traditionally been

protected if not by an absolute privilege, supra, p. 10, at

least by a qualified privilege. See, e.g., Sivaaley v. United

States, 376 F.2d 857 (U.S. Ct. Claims 1967); Annot., 140

A.L.R. 1466 (1942).

The court below held that the issue of malice was for the

trier of fact But the question of whether, as a matter of

law, malice can be found on this record, is one for this

Court. See New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254,

285 and n. 26 (1964).

The allegedly defamatory charge at issue in this case

is one of police brutality, an expression of Petitioner’s

opinion based on facts outlined in his letter. Since the

claim of defamation was based only on this statement of

opinion, and not on specific factual statements, it is argu

able that no action for defamation lies at all. See Gar

rison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64, 77 and n. 10 (1964). In

13

any event, a defense of fair comment must be afforded

under Times v. Sullivan for an bonest expression of

opinion based upon privileged, as well as true, statements

of fact, 376 U.S. at 292 n. 30. See generally Noel, Defa

mation of Public Officers and Candidates, 49 Colum. L.J.

875, 879 (1949). It was for Respondent to defeat this

defense by a showing of malice—a showing that Petitioner’s

allegation of police brutality was unsupported except by

statements of fact made with knowledge that they were

false or with reckless disregard of whether they were

false or not, Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. at 279-280. In

fact, Petitioner’s allegation was supported by numerous

statements in his letter which were never even denied by

Respondent: The allegations that he was held on the

ground while handcuffed behind his back; that the hand

cuffs were excruciatingly tight and his continual pleas

to loosen them ignored; and that Sergeant Pilliben made

numerous demeaning and intimidating comments. More

over, Respondent Pilliben introduced no evidence denying

that the conversation relating to police brutality took

place as described in the letter, which was admitted into

evidence in full.8 In that conversation Sergeant Pilliben,

when Petitioner implied that he had been subjected to

police brutality, not only failed to deny, but implicitly

acknowledged the truth of the allegation. (App. 12a, infra)

Certainly these facts would alone support an honest belief9

by Petitioner that he had been subjected to police brutality.

Respondent’s proof that certain of the facts reported in

the letter were false seems therefore irrelevant.

8 See n. 1, pp. 5-6, supra.

9 The fact that an opinion is unreasonable is immaterial. See,

e.g., New York Times v. Sullivan, supra, 376 U.S. at 292, n. 30;

Noel, Defamation of Public Officers and Candidates, 49 Colum’

L.J. 875, 879 (1949).

14

Moreover, the insignificant discrepancies between Peti

tioner’s and Respondent’s versions10 cannot constitutionally

support a finding of malice. See e.g., Pickering v. Board

of Educ., 291 U.S. 563 (1968); New York Times Co. v.

Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 286, 289 (1964). It is inevitable

that an event like this will produce somewhat different

versions and interpretations of exactly what happened.11

To allow a jury to find malice solely on the basis of such

discrepancies as exist between Petitioner’s story and the

evidence Respondent introduced would be to subject vir

tually every person complaining of police abuse to the

risk of damages and to place an intolerable burden on

the rights of citizens to seek redress for legitimate griev

ances.

10 Respondent’s witnesses testified that Petitioner acted provoca

tively at the time of his arrest—cursing and waving his arms—

and after he was handcuffed—-kicking at the officers. And Respon

dent’s witnesses indicated that Petitioner fell or was dropped,

rather than pushed, to the ground.

11 Petitioner in this case was arrested for speeding at midnight,

after a long day, on his way back to work; he testified that he was

not driving fast and the evidence indicated that he was never con

victed on the charges for speeding or for failing to heed an officer’s

signal; he was pursued and stopped by an officer driving in an

ordinary car, and he testified that he did not know what was

going on when he was asked to get out of his car. It is understand

able, even accepting completely the version of the incident most

favorable to Respondent’s case, that Petitioner might feel that each

assertion of police authority from the initial order to get out of his

car on, was unwarranted, that he was justified in resisting such

assertions and, therefore, that the entire incident represented an

abuse by the police of his rights. In this context it is perfectly

possible for him to have believed that he was pushed to the ground

even if, in fact, he fell or was dropped.

15

For the Foregoing Reasons, Certiorari Should

Be Granted

Respectfully submitted,

Louis L. R edding

400 Farmers Bank Building

919 Market Street

Wilmington, Delaware 19801

J ack Green b er g

J am es M. N abrit , III

M ic h a e l M e l t sn e r

M elvyn Z arr

E liza b eth B. DuB ois

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioner

APPENDIX

APPENDIX A

Opinion Below

I n t h e

S u p r e m e C ourt op t h e S tate op D elaw are

No. 43, 1968

J o se ph F. F il l ib e n , J r.,

Plaintiff Below, Appellant,

v.

J o se ph B e n J a ck so n , J r .,

Defendant Below, Appellee.

October 25, 1968

W olcott, Chief Justice; C arey and H e r r m a n n , JJ., sitting.

Upon appeal from the Superior Court. Reversed and

remanded.

Harold Leshem, of Booker, Leshem, Green & Shaffer,

Wilmington, for plaintiff below, appellant.

Louis L. Redding, Wilmington, for defendant below,

appellee.

Carey, Justice:

The appellant, Joseph F. Filliben, Jr., brought suit in

Superior Court against the appellee, Joseph Ben Jackson,

Jr., seeking damages for an alleged defamation. After

plaintiff’s case in chief was completed, the trial Court di-

la

2a

rected a verdict in favor of the defendant. It is this ruling

which is now questioned.

The appellant, who was a police officer, alleged in his

complaint that the appellee maliciously made formal

charges against him to the United States Attorney, know

ing them to be false. According to the complaint, the

alleged untrue charges accused him of “police brutality.”

At the trial, the appellee admitted that he did have a

conversation with the Federal District Attorney, but the

record does not disclose precisely what statements were

then made by the appellee. There was introduced into evi

dence, however, a letter written by appellee to Joseph

Errigo, who was at the time Commissioner of Public Safety

for the City of Wilmington. It was also shown that a copy

of that letter was delivered to the Federal Bureau of In

vestigation. This letter, admitted into evidence without

objection, constituted the basis of the complaint.

The motion for directed verdict was based on the ground

that there was a fatal variance in that there was no proof

of any defamatory statement made to the United States

Attorney as alleged in the complaint. The Court’s ruling

was based solely upon that ground. Appellant argues that

the ruling was incorrect because, when the letter was ad

mitted into evidence without objection, the pleadings were

impliedly amended under Superior Court Civil Rule 15(b).

We agree with that contention.

Rule 15(b) is precisely the same as the Federal Rule of

Civil Procedure bearing the same designation. Under it,

failure to object to the admission of testimony is an implied

consent to the amendment. 3 Moore’s Federal Practice

(2nd ed.) 994; Eisenrod v. Utley, 211 F. 2d 678. Such is the

situation in the present case. The evidence showed a pub

lication to the Commissioner of Public Safety (appellant’s

highest superior) and to the Federal Bureau of Investiga

tion, rather than to the United States District Attorney;

3a

the variance consisted solely in tile identity of the persons

to whom the charges were made. Direction of the verdict

was accordingly unjustified.

Appellee’s brief raises for the first time two additional

arguments to support his contention that the judgment

should be affirmed despite the error mentioned above. Al

though these contentions have not been passed upon by

the Court below, we will rule upon them for the guidance

of the trial Judge in the future handling of the case.

The first contention is that the letter written by appellee

“is so vague, inconclusive and nebulous that it could not

justify a verdict that defendant made a defamatory ut

terance relating to plaintiff.” This proposition, in our opin

ion, is a matter for the trier of fact. A jury could rea

sonably find that the letter charges the appellant with the

use of excessive and unjustified physical force in arresting

the appeellee which, in our opinion, is the equivalent of

“police brutality;” indeed, appellant testified that, if the

charges had been found to be true, they would have justi

fied his dismissal from the force. We find no merit in this

argument.

Secondly, appellee contends that the appellant, as a po

lice sergeant, was a public official within the meaning of

New York Times Company v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254, 84

S. Ct. 710, and that there Was no showing of malice as de

fined in that case. Assuming, without deciding, that appel

lant was a “public officer,” we are of the opinion that the

issue of malice is a matter for the trier of fact. The appel

lant denied the truth of the charges; their nature is such

that the jury could properly find that appellee actually

knew they were false. Such a finding would suffice to dem

onstrate malice, under the Sullivan rule, supra. See Ross

v. News-Journal Company,------ Storey----- , 228 A. 2d 531.

The judgment below must be reversed and remanded for

further proceedings consistent herewith.

4a

APPENDIX B

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

18 U.S.C. §241

§241. Conspiracy against rights of citizens

If two or more persons conspire to injure, oppress,

threaten, or intimidate any citizen in the free exercise or

enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the

Constitution or laws of the United States, or because of

his having so exercised the same; or

If two or more persons go in disguise on the highway,

or on the premises of another, with intent to prevent or

hinder his free exercise or enjoyment of any right or

privilege so secured—

They shall be fined not more than $5,000 or imprisoned

not more than ten years, or both.

18 U.S.C. §242

§242. Deprivation of rights under color of law

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any inhabitant of

any State, Territory, or District to the deprivation of

any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected

by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or to

different punishments, pains, or penalties, on account of

such inhabitant being an alien, or by reason of his color,

or race, than are prescribed for the punishment of citizens,

shall be fined not more than $1,000 or imprisoned not

more than one year, or both.

5a

28 U.S.C. §1257

§1257. State courts; appeal; certiorari

Final judgments or decrees rendered by the highest

court of a State in which a decision could be had, may be

reviewed by the Supreme Court as follows:

(1) By appeal, where is drawn in question the validity of

a treaty or statute of the United States and the decision is

against its validity.

(2) By appeal, where is drawn in question the validity

of a statute of any state on the ground of its being repug

nant to the Constitution, treaties or laws of the United

States, and the decision is in favor of its validity.

(3) By writ of certiorari, where the validity of a treaty

or statute of the United States is drawn in question or

where the validity of a State statute is drawn in question

on the ground of its being* repugnant to the Constitution,

treaties or laws of the United States, or where any title,

right, privilege or immunity is specially set up or claimed

under the Constitution, treaties or statutes of, or commis

sion held or authority exercised under, the United States.

June 25, 1948, c. 646, 62 Stat. 929.

42 U.S.C. §1983

§1983. Civil action for deprivation of rights

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory,

subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the

United States or other person within the jurisdiction

thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or

immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall

be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in

equity, or other proper proceedings for redress. R.S.

§1979.

6a

42 U .S .C . §1985

§1985. Conspiracy to interfere with civil rights—Pre

venting officer from performing duties

(1) If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire to prevent, by force,, intimidation, or threat, any

person from accepting or bolding any office, trust, or place

of confidence under the United States, or from discharging

any duties thereof; or to induce by like means any officer

of the United States to leave any State, district, or place,

where his duties an an officer are required to be performed,

or to injure him in his person or property on account of

his lawful discharge of the duties of his office, or while

engaged in the lawful discharge thereof, or to injure his

property so as to molest, interrupt, hinder, or impede

him in the discharge of his official duties;

(2) If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire to deter, by force, intimidation, or threat, any

party or witness in any court of the United States from

attending such court, or from testifying to any matter

pending therein, freely, fully, and truthfully, or to in

jure such party or witness in his person or property on

account of his having so attended or testified, or to in

fluence the verdict, presentment, or indictment of any grand

or petit juror in any such court, or to injure such

juror in his person or property on account of any ver

dict, presentment, or indictment lawfully assented to by

him, or of his being or having been such juror; or if

two or more persons conspire for the purpose of impeding,

hindering, obstructing, or defeating, in any manner, the

due course of justice in any State or Territory, with in

tent to deny to any citizen the equal protection of the laws,

or to injure him or his property for lawfully enforcing, or

attempting to enforce, the right of any person, or class

of persons, to the equal protection of the law;

7a

(3) If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire or go in disguise on the highway or on the prem

ises of another, for the purpose of depriving, either di

rectly or indirectly, any person or class of persons of the

equal protection of the laws, or of equal privileges and

immunities under the laws; or for the purpose of prevent

ing or hindering the constituted authorities of any State

or Territory from giving or securing to all persons within

such State or Territory the equal protection of the law;

or if two or more persons conspire to prevent by force,

intimidation, or threat, any citizen who is lawfully entitled

to vote, from giving his support or advocacy in a legal

manner, toward or in favor of the election of any lawfully

qualified person as an elector for President or Vice Presi

dent, or as a Member of Congress of the United States;

or to injure any citizen in person or property on account

of such support or advocacy; in any case of conspiracy

set forth in this section, if one or more persons engaged

therein do, or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of

the object of such conspiracy, whereby another is injured

in his person or property, or deprived of having and

exercising any right or privilege of a citizen of the United

States, the party so injured or deprived may have an

action for the recovery of damages, occasioned by such

injury or deprivation, against any one or more of the

conspirators. E.S. §1980.

8a

APPENDIX C

Letter from Petitioner to the Police Commissioner

605 S. Heald Street

Wilmington, Delaware

December 5, 1965

Joseph A. Errigo

Commissioner of Police

Department of Public Safety

Public Building

Wilmington, Delaware

Dear Mr. Errigo:

As per your instructions I am submitting this letter to

you as an official complaint of abuse by Police.

On Thursday night, December 2, 1965, between 11:30 and

midnight, I was a victim of unprovocative abuse by uni

formed city policeman. At 8 :00 P.M., Thursday, December

2, 1965 I was excused from work at General Motors to at

tend the funeral of Andrew Smith at Mother A.U.M.P.

Church, 819 French Street, to perform the last rites over

him in my capacity as High Priest of Royal Arch Masons

of Delaware. It was agreed that I would return to work

to finish the shift.

Shortly after 11:30 P. M., on the date mentioned above, I

was travelling alone in my automobile west on Delaware

Avenue. I was attired in a tuxedo because I could change

to my work clothes later. As I travelled in a westerly di

rection there was one automobile in front of me and one

directly behind. Upon approaching Adams Street I indi

cated a left turn with my directional signals. After I made

the bend to the right I indicated a left turn approaching

9a

Jackson Street. The car directly behind me started blow

ing Ms born and pulled over to the left across the double

lines and drove up as far as my left rear door. Not know

ing what his intentions were I was forced to continue turn

ing right to avoid an accident. As I continued on Delaware

Avenue and then to Pennsylvania Avenue, the automobile

mentioned before was still in front of me in the left lane.

The automobile behind me continued to blow the horn and

weave across the double lines and then back behind me.

After I passed Harrison Street, I indicated a left turn

at the next intersection which would have been Franklin

Street. The automobile in front of me in the left lane

stopped and I applied my brakes to stop. The automobile

behind me again crossed the double lines and stopped and

about the same time another automobile approaching on

the right stopped directly beside me. Emerging from the

automobile in front of me was a uniform policeman and as

he came in my direction he was inquiring as to what was

the matter. A uniformed policeman emerged from the car

on the right and snatched open the front door and almost

simultaneously another uniform policeman whom I recog

nized to be Sgt. Filliben emerged from the car that had

been behind me and was now stopped on my left snatched

open the left front door and in extremely harsh demanding

tones said “Ben get out of the car”. I said, “what hap

pened!” Sgt. Filliben then said “Ben get the hell out of the

car, dammit”. I asked him again what I had done. He then

said “Are you going to get out Ben, or do I have to take

you out!” The officer on the right, whom I did not recog

nize told me I had better get out and went around the back

of my automobile and as I stood up Sgt. Filliben yoked me

around the neck twisting it while the officer that went

around the back of my automobile put my hands' behind

my back and snapped hand cuffs on my wrist causing un

10a

bearable pain. I was then thrown to the ground. I tried

to get up several times but each time I was knocked back

down. Sgt. Filliben then told one of the officers to hold me

down and he immediately complied by dropping down upon

me with his knee. I tried vainly to get up. I asked the of

ficer repeatedly to let me up and loosen the hand cuffs.

I told him that the hand cuffs were hurting me. He said

“Shut up”. I asked him why couldn’t I get up. He said,

“because I don’t want you to.”

During this time Sgt. Filliben walked to the south side

of Pennsylvania Avenue and said something to a man that

was standing there. The man then disappeared. Traffic

continued to move but to my knowledge no one stopped.

When Sgt. Filliben returned he said that the wagon was

coming. I was then picked up from the ground and the

Sgt. said, “Put him in the wagon”. I said, “Wait a minute

please and will someone please tell me what I have done!”

The Sgt. said, “Put him in the wagon”. I asked “Why do

I have to go in the Patrol Wagon!” Sgt. Filliben at this

instant grabbed me and slammed me back down on the

ground and said, “Let him stay there until he decides to

get up”. After a few minutes he asked if I was ready to

get up, I asked him to please get me up and loosen the

hand cuffs. I was picked up and put into the patrol wagon.

I asked the officer in the back with me to loosen the hand

cuffs or take them off because the pain was getting worse.

He informed me that he did not have a key to fit them. The

driver of the patrol wagon then proceeded to answer a call

in the vicinity of 6th and Wallaston Streets. There they

picked up a woman. After this the driver went past the

police station and over 11th Street Bridge to pick up a man.

All during the ride I was begging and pleading for relief

of the pain on my wrist.

11a

After I was taken into the station the officer who had told

me that he didn’t have a key to fit the hand cuffs on my

wrists, selected one from a hunch of keys in his possession

and caused me to bend over with my head almost between

my knees. He then unlocked the hand cuffs. My wrists

were terribly bruised, particularly the left one.

After a few sighs of relief I asked the officer, commonly

known as the turn key what my bail was. He said, “I don’t

know Ben, I haven’t received any charge”. Sgt. Filliben

then came down the steps and said, “You’ve got plenty of

them. Speeding, Disorderly Conduct, Resisting Arrest, and

Assault and Battery on a Police Officer.” In amusement 1

asked, “When did all this happen?” The Sgt. then replied,

“That’s what you are charged with”. He then asked me if

I wanted to have the case continued? I told him that I

didn’t know, but I would like to know what my bail was.

He said that it would probably be around $1000.00 and

again inquired if I wanted to continue the case. I told

him that I didn’t know and all I wanted at the time was

to get out of there. I asked if I could sign my own “O.R.”

and was refused instantly. I was told I would have to get

someone to bail me out or stay there. I asked if I could use

the telephone and the turn key told me “yes”. Sgt. Filliben

wanted to know who I was going to call, I told him “Junius”.

He said “who!” “Reynolds! Do you think he will come

and get you?” I told him that I thought that he would. He

again inquired as to whether I wanted the case continued.

Again I told him that I didn’t know. I called Reynolds and

made the arrangements to be released. I then asked the

turn key if I could call General Motors to tell them that

I had been detained at Police Headquarters. He gave me

permission to do so. I started to make a third call to bor

row money to get my automobile that was left at the scene

with the motor running and lights on because the Sgt. told

12a

me that it would be impounded but was told to hang up.

Sgt. Filliben then asked me again if I was going to have

the case continued? I said to him “I really don’t know”.

I have often read and heard of police brutality but had no

idea that I would ever experience it.” Sgt, Filliben then

said, “you’re lucky. Ten years ago I would have black

jacked you”. I said, “What did you say?” I would have

black jacked you ten years ago, you’re lucky boy.” I said,

“With hand cuffs on?” He said, “That’s right boy you’re

lucky.” He then demanded that I tell him whether or not

I was going to have the case continued. I asked him what

was the urgency and if he was on day work. He told me he

was on 4 to 12. He then said, “I ’ll tell you what you’re going

to do”. You’re going to have this case tomorrow morning

and if it is continued I will turn in my stripes. He then

went up stairs.

Reynolds came and I was released. I asked Sgt. Sullivan

for a permit to release my car and he gave it to me. The

next morning while sitting on a bench in the hall of the

Public Building reading a newspaper at about 8 :40 A. M.,

Sgt. Filliben approached me and said, “Ben are you going

to have this case continued?” I said nothing. He repeated

the question and I did not answer him. He then said, “all

right boy, I just gave you your last chance” as though to

threaten me.

I have always had an excellent relationship with the

members of the police department. Many of them know me

as a former city official in the capacity of City Auditor.

Prior to that office many of them had escorted me to the

banks in the city protecting tax money when I was the

Deputy Tax Collector.

I am at a complete loss beyond comprehension as to

why I was administered such abuse by men who are sup

pose to be protectors of the citizens of Wilmington.

13a

My cries for “Help” would have been in vain because

who would stop to question uniformed police. The officers

were each riding in separate cars, none of which were po

lice cars.

I am appealing to you to investigate this incident thor

oughly as to why it happened.

Respectfully yours,

/ s / J o s e p h B. J a c k s o n J r.

Joseph B. Jackson Jr.

MEilEN PRESS INC. — N. Y C. «^g^ i»2 ?9