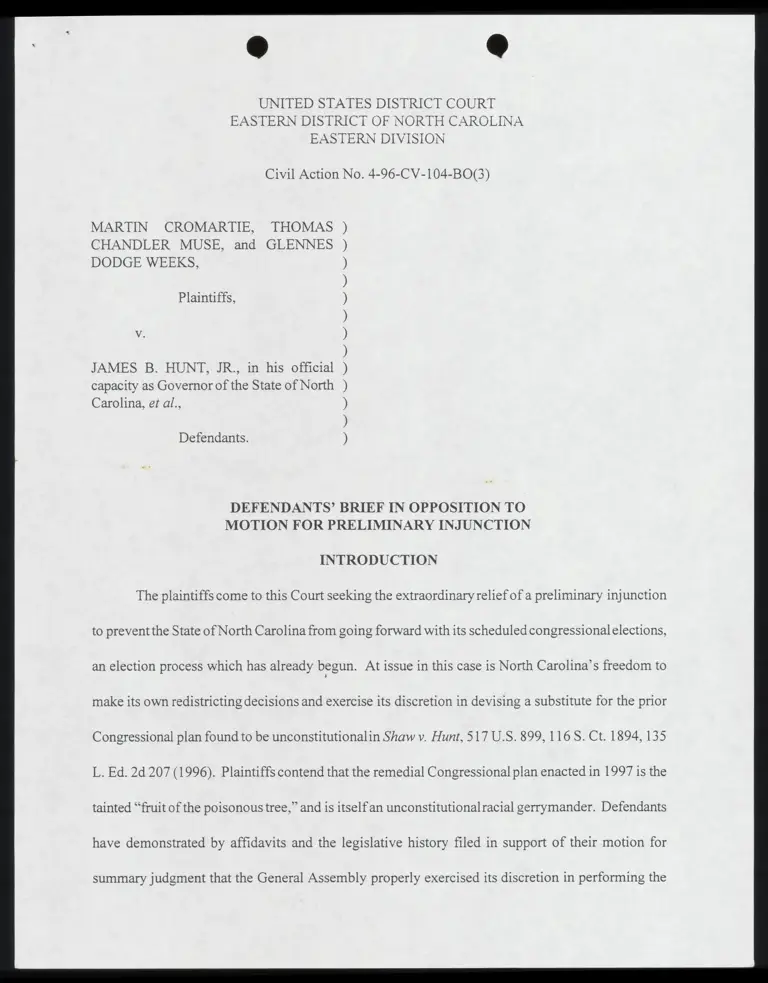

Defendants' Brief in Opposition to Motion for Preliminary Injunction with Certificate of Service, Affidavits Filed by Defendants Relating to Summary Judgment and Preliminary Injunction Proceedings, and Additional Affidavits Filed by Defendants Relating to Preliminary Injunction Proceedings

Public Court Documents

March 20, 1998

227 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Defendants' Brief in Opposition to Motion for Preliminary Injunction with Certificate of Service, Affidavits Filed by Defendants Relating to Summary Judgment and Preliminary Injunction Proceedings, and Additional Affidavits Filed by Defendants Relating to Preliminary Injunction Proceedings, 1998. e4d2b22c-d90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c61bea79-024f-4cae-870a-840adbc863fc/defendants-brief-in-opposition-to-motion-for-preliminary-injunction-with-certificate-of-service-affidavits-filed-by-defendants-relating-to-summary-judgment-and-preliminary-injunction-proceedings-and-additional-affidavits-filed-by-defendants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

EASTERN DIVISION

Civil Action No. 4-96-CV-104-BO(3)

MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS )

CHANDLER MUSE, and GLENNES )

DODGE WEEKS,

Plaintiffs,

v.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official

capacity as Governor of the State of North

Carolina, et al.,

Defendants.

N

r

”

N

t

?

S

e

w

?

N

a

?

N

w

N

w

Na

tt

’

S

u

Su

nt

!

a

t

?

u

w

’

DEFENDANTS’ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO

MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

INTRODUCTION

The plaintiffs come to this Court seeking the extraordinary relief of a preliminary injunction

to prevent the State of North Carolina from going forward with its scheduled congressional elections,

an election process which has already begun. At issue in this case is North Carolina’s freedom to

make its own redistricting decisions and exercise its discretion in devising a substitute for the prior

Congressional plan found to be unconstitutionalin Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899, 116 S. Ct. 1894, 135

L. Ed. 2d 207 (1996). Plaintiffs contend that the remedial Congressional plan enacted in 1997 is the

tainted “fruit of the poisonous tree,” and is itself an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. Defendants

have demonstrated by affidavits and the legislative history filed in support of their motion for

summary judgment that the General Assembly properly exercised its discretion in performing the

legislative task of correcting the constitutional violation, and further, that race was not the

predominate factor motivating the legislature’s redistricting decisions.

Enjoining an election which has already begun is an extraordinary remedy that would deny

the voters of North Carolina the opportunity to elect members of Congress in a meaningful and

orderly manner and would frustrate the public interest. An injunction stopping an ongoing

congressional election process “is serious business.” Oden v. Brittain, 396 U.S. 1210, 90 S. Ct. 4,

24 L. Ed. 2d 32 (1969) (Black, J., opinion in chambers). Plaintiffs’ contentions cannot withstand

defendants’ motion for summary judgment, and the State of North Carolina and its voters must be

allowed to proceed to elect their twelve members of Congress. For the reasons discussed herein and

in defendants’ brief in support of their motion for summary judgment, defendants urge the Court to

deny plaintiffs’ request for preliminary injunction and to grant summary judgment dismissing

plaintiffs’ action altogether.

In addition to the affidavits and materials filed in support of their motion for summary

judgment, defendants also rely on the following affidavits filed contemporaneously with this brief:

Congressman Walter B. Jones Congressman Bob Etheridge

Congresswoman Sue Myrick Congressman David E. Price

Congressman Charles H. Taylor Gary O. Bartlett, Executive Secretary-Director

of the N.C. State Board of Elections

Congresswoman Eva M. Clayton (Second Affidavit)

On March 2, 1998, defendants filed the Affidavits of Senator Roy Cooper, III,

Representative Edwin McMahan, Dr. David R. Goldfield, Dr. David W. Peterson, Dr. Alfred W.

Stuart, Dr. Gerald R. Webster, and Gary O. Bartlett (hereinafter © Aff.”).

2

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Following the July 9, 1996, remand for remedial proceedings in Shaw, plaintiffs Martin

Cromartie, Thomas Chandler Muse and Glennes Dodge Weeks filed their original action challenging

Congressional District 1. On that same day, Mr. Cromartie, Mr. Muse and Ms. Weeks also moved

to amend the complaint in Shaw to be added as plaintiffs for the remedial phase, a motion which was

allowed. A stay was entered in this action pending completion of the remedial phase in Shaw.

The Shaw Court on August 8, 1996, enjoined North Carolina from using the 1992 plan after

the 1996 election and directed the General Assembly to submit a new plan for the Court’s approval

by April 1, 1997. On August 21, 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected plaintiffs’ efforts to

overturn that order. On March 31, 1997, a new congressional redistricting plan was enacted

(hereinafter “1997 plan”) and submitted to the Shaw Court for approval. After preclearance by the

United States Department of Justice, plaintiffs, including Cromartie, Muse and Weeks, were offered

the opportunity to present any opposition to the plan. They elected not to challenge the

constitutionality of the remedial plan. On September 12, 1997, the Shaw Court ordered the new plan

“APPROVED as having adequately remedied the specific constitutional violation respecting former

congressional District 12.” No appeal was filed from that order.

On October 17, 1997, the stay in this case was dissolved and plaintiffs filed their amended

complaint challenging Districts 1 and 12 and the State’s newly approved congressional plan as an

unconstitutional racial gerrymander. Although the candidate filing period for the United States

House of Representatives opened at noon on January 5, 1998, and closed at noon on February 2,

1998, plaintiffs delayed until January 30, 1998, the Friday on the eve of the close of the candidate

~

0

filing period, to file a motion for preliminary injunction; not until February 23, 1998, did plaintiffs

file a brief in support of their preliminary injunction motion.

While plaintiffs tarried, the election process began. Thirty-one candidates filed notice of

candidacy and contested primaries will be held in eight of the State’s twelve congressional districts.

County boards of elections have updated their records assigning voters to their districts and have

notified voters of their districts; voter lists have been made available to candidates. Ballots have

been designed, printed and distributed, and voting began March 16, 1998, the first day of absentee

voting. Publication in local newspapers of the first notice of the primary elections and the

registration deadline was completed March 21, 1998. The last day to register to void for the primary

is April 10, 1998. The primaries will take place May 5, 1998, along with primaries for other state,

federal and local offices. Millions of dollars have already been raised and spent by congressional

candidates.? Much time and effort has already been expended by candidates organizing their

campaigns and familiarizing themselves with the voters in the newly configured districts. The

candidates have been campaigning to provide the voters with their views on issues of concern to

each district’s citizens. Citizens and community leaders have already informed themselves about

their districts and the candidates in their districts, and many are actively involved in the candidates’

campaigns.’ Plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction comes far too late and should be denied

i

in this case where the “election machinery is already in progress” and “an impending election is

Eo)

2 See Second Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett, Executive Secretary-Director of the North

Carolina State Board of Elections (hereinafter “Second Bartlett Aff.”), filed March 20, 1998.

3 See Affidavits of Congresspersons Walter B. Jones, Sue Myrick, Charles H. Taylor,

Eva M. Clayton, Bob Etheridge and David E. Price (hereinafter Aff.”), filed March 20, 1998.

4

imminent.” Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 585, 84 S. Ct. 1362, 1394, 12 L. Ed. 2d 506, 541

(1964).

ARGUMENT

I. THE STANDARD FOR EVALUATING PLAINTIFFS’ REQUEST FOR

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTIVE RELIEF.

“Federal decisions have uniformly characterized the grant of interim relief as an

extraordinary remedy involving the exercise of a very far-reaching power, which is to be applied

‘only in [the] limited circumstances’ which clearly demand it.” Direx Israel, Ltd. v. Breakthrough

Med. Corp., 952 F.2d 802, 811 (4th Cir. 1991). Because it “is an extraordinary remedy, the right

to relief must be clear and unequivocal” to justify issuance of a preliminary injunction. SCFC ILC,

Inc. v. Visa USA, Inc., 936 F.2d 1096, 1098 (10th Cir. 1991) (citation omitted); see also Federal

Leasing, Inc. v. Underwritersat Lloyd's, 650 F.2d 495,499 (4th Cir. 1981) (“award of a preliminary

injunction is an extraordinary remedy, to be granted only if the moving party clearly establishes

entitlement to the relief sought”).

Plaintiffs in their motion and supporting brief fail even to acknowledge the extraordinary and

drastic nature of the preliminary injunction they seek. They utterly ignore the “even heavier burden”

imposed on a movant seeking any of three types of “disfavored” preliminary injunctions:

(1a preliminary injunction that disturbs the status quo; (2) a preliminary injunction

that 1s mandatory as opposed to prohibitory; and (3) a preliminary injunction that

affords the movant substantially all the relief he may recover at the conclusion of a

full trial on the merits.

SCFC ILC, 936 F.2d at 1098-99. Here, the injunction sought by plaintiffs falls into two of the three

disfavored categories because it would disrupt the status quo and would grant plaintiffs the relief

sought prior to a decision on the merits.

“The foundational principle for preliminary relief is that ‘it is a sound idea to maintain the

status quo ante litem, provided that it can be done without imposing too excessive an interim burden

upon the defendant.” Feller v. Brock, 802 F.2d 722, 727 (4th Cir. 1986) (quoting Blackwelder

Furniture Co. v. Seilig Mfg. Co., 550 F.2d 189, 195 (4th Cir. 1977). Indeed, it has been said that the

very purpose of a preliminary injunction is to maintain the status quo until the case can be resolved

on the merits. See Wetzel v. Edwards, 635 F.2d 283, 286 (4th Cir. 1980); Morgan v. Fletcher, 518

F.2d 236, 239 (5th Cir. 1975). That status quo, “the last uncontested status between the parties

which preceded the controversy until the outcome of the final hearing,” Stemple v. Board of Educ.

of Prince George's County, 623 F.2d 893, 898 (4th Cir. 1980), will not be preserved in this case if

the Court undertakes to upset it by granting plaintiffs’ motion to enjoin the election. Instead of

maintaining the status quo, a preliminary injunction in this case disrupts it by compelling the State

to abandon an election in progress.

In addition, the burden on a “party seeking a preliminary injunction is especially heavy when

the relief sought would in effect grant plaintiff a substantial part of the relief it would obtain after

a trial on the merits.” GTE Corp. v. Williams, 731 F.2d 676, 679 (10th Cir. 1984). The injunctive

relief sought by plaintiffs would grant them the ultimate relief they seek, at least for the 1998

elections. This procedure “is similar to the ‘Sentence first -- Verdict Afterwards’ type of procedure

parodied in Alice in Wonderland, which is an anathema to our system of jurisprudence.” SCFC ILC,

936 F.2d at 1099.

This Court must balance four factors in determining whether the exercise of the “far-reaching

power of a preliminary injunction” is “clearly demanded:” (1) the irreparable harm to the plaintiffs

if the relief is denied; (2) the harm to the defendants if the relief is granted; (3) the likelihood of

6

plaintiffs’ success on the merits; and (4) the public interest. Blackwelder Furniture Co., 550 F.2d

189 (4th Cir. 1977); Rum Creek Coal Sales, Inc. v. Caperton, 926 F.2d 353 (4th Cir. 1991).

Plaintiffs seeking preliminary relief bear “the burden of establishing that each of these factors

supports granting the injunction.” Direx Israel, 952 F.2d at 812. A sequential process is followed

in determining whether the plaintiffs have carried this burden. The first step is to determine whether

plaintiffs have “made a ‘clear showing’ of irreparable injury absent preliminary injunctive relief.”

Direx Israel, 952 F.2d at 812. The next step is to balance any irreparable injury the plaintiffs have

proved against harm to defendants. If the plaintiffs have proved that “the balance of hardship tips

decidedly” in their favor, they must go on to prove “that the dispute presents a serious issue for

litigation and that the injunction will serve the public interest.” Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner &

Smith, Inc. v. Bradley, 756 F.2d 1048, 1054-55 (4th Cir. 1985) (emphasis added). “As the balance

[of harm] tips away from the plaintiffs], a stronger showing on the merits is required.” Direx Israel.

952 F.2d at 313.

This well-established standard has been applied in weighing requests to preliminarily enjoin

elections. See, e.g., Republican Party of Va. v. Wilder, 774 F. Supp. 400 (W.D. Va. 1991) (three-

judge court) (applying the foregoing factors in denying injunction against Virginia legislative

elections). Application of these standards to this case demonstrates that the plaintiffs are not entitled

to the injunction they request.

IL. PLAINTIFFS HAVE NOT MADE A CLEAR SHOWING OF IRREPARABLE HARM

IF AN INJUNCTION IS NOT ISSUED.

Proof of irreparable injury “is the single most important prerequisite for the issuance of a

preliminary injunction.” Citibank, N.A. v. Citytrust, 756 F.2d 273, 275 (2nd Cir. 1985) (citing 11

CHARLES ALAN WRIGHT & ARTHUR R. MILLER, FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE § 2948 at 431

(1993)). See also Sampson v. Murray, 415 U.S. 61, 88.94 S. Ct. 937,951-52,39 L. Ed. 2d 166, 185

(1974), quoted in Direx Israel, 952 F.2d at 812 (“*[t]he basis of injunctive relief in the federal courts

has always been irreparable harm and inadequacy of legal remedies”). “Moreover, the required

irreparable harm must be neither remote nor speculative, but actual and imminent.” Direx Israel,

952 F.2d at 812 (internal quotes and citations omitted). See also Dan River, Inc. v. Icahn, 701 F.2d

278.284 (4th Cir. 1983) (preliminary injunction denied because of absence of proof of immediate

irreparable harm). Plaintiffs in this case have failed to meet their burden of making a clear showing

of irreparable harm absent the entry of a preliminary injunction.

The plaintiffs argue two possible types of harm which they contend support entry of a

preliminary injunction enjoining the impending election: representationalharm and stigmatic harm.

Neither of the harms is irreparable and both presuppose that plaintiffs will win on the merits of their

claim. In suggesting representational harm, plaintiffs rely on the Court’s concern in Shaw that when

a district is racially gerrymandered “elected officials are more likely to believe that their primary

obligation is to represent only members of that group, rather than their constituency as a whole.”

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630, 648, 113 S. Ct. 2816,2827, 125 L. Ed. 2d 511, 529 (1993). Plaintiffs

do not present any concrete examples of representational harm they personally have suffered; instead

they make the conclusory allegation: “Plaintiffs and all other North Carolina voters - black and

white - have already been suffering this ‘representational’ harm since November 1992.” See

Plaintiffs’ Brief in Support of Motion for Preliminary Injunction at 6. The fallacy of this theory of

harm is that the constitutional violation in the 1992 plan already has been remedied and further

elections under the unconstitutional plan enjoined.

8

The election underway now is under the new 1997 plan and plaintiffs can show potential

representational harm only if they win on the merits by proving an unconstitutional racial

gerrymander. The 1997 plan, however, was the result of a bipartisan agreement first, to cure the

constitutional defects in the 1992 plan by assuring that race was not the predominate factor to which

traditional criteria were subordinated; and second, to maintain the existing partisan balance of six

Republicans and six Democrats in the State’s congressional delegation.® In achieving these goals,

the 1997 plan substantially altered the shapes and make-ups of the districts. The district lines respect

precinct boundaries and “cross-overs” and single points of contiguity were not used to connect

population groups.’ Almost 35% of the geographic area and almost 33% of the population of

District 1 were shifted into other districts; similarly, over 58% of the geographic area and almost

32% of the population of District 12 were assigned to different districts.® The travel times and

distances for District 12 improved dramatically (it now has the third shortest travel time of 1.67

hours and covers a distance of 95 miles), while District 1 improved substantially (the travel time is

now three hours or less and the distance extends 150 miles or less, depending on the route).’

District 1 is now a bare African-American majority in total population (50.27%), although it is

majority white in voting age population and voter registration; District 12 is no longer an African-

American majority district.®

$ See Cooper Aff. 91 3, 5 and 7-9; McMahan Aff. § 3, 5-7 and 9-10.

5 See Cooper Aff. § 7.

$ See Webster Aff., Rpt. pp. 24-25, and Tbls. 7 & 8.

? See Stuart Aff. 99 8 and 10-11, and This. 1 & 2.

! See Bartlett Aff., Vol. 1 at 97C-27A-2, p. 25.

9

Plaintiffs’ theoretical claim of representational harm lacks any evidentiary support. By

contrast, Congresswoman Eva Clayton necessarily is aware that she represents “the entire First

District, not just the minority voters in the district.” She is responsive to the shared needs and

concerns of this rural and economically poor region, needs and concerns which “transcend race.”

Under the circumstances of this case, plaintiffs will be hard-pressed not only to establish the merits

of their claim, but also to prove an actual or imminent prospect of representational harm.

The other harm proffered by plaintiffs, that of stigmatization or racial stereotyping, suffers

the same flaws. In addition to the integrated demographics of the challenged districts, other

circumstances contradict any suggestion of offensive and demeaning racial stereotyping. Plaintiffs

concede that the location of District 1 in the northeastern Coastal Plain has historical and

demographic legitimacy.” Demeaning racial stereotyping is certainly not present in District 12. It

is a distinctly urban district in which white citizens constitute a majority.

Finally, even accepting plaintiffs’ alleged harm at face value, a separate independent reason

why the plaintiffs’ request for injunctive relief must fail is that the harm alleged by plaintiffs is not

irreparable as a matter of law. The Court has full remedial powers to fashion relief if, after hearing

all the evidence in the case, it concludes that the current redistricting plan violates the constitution.

In appropriate circumstances, relief may even be given by means of special elections, Ketchum v.

City Council of Chicago, Ill., 630 F. Supp. 551, 565 (N.D. Ill. 1985) (“Federal courts have often

: See Clayton Aff. q 13.

2 See Mortimer Aff. p. 9.

10

ordered special elections.”), or by deferring relief to the next election cycle. Republican Party of

Va., 774 F. Supp. at 407.

The lack of irreparable harm is an insurmountable barrier to plaintiffs’ claim for preliminary

injunctive relief. Alleged harm which can be repaired in the future is simply not irreparable harm.

As the Fifth Circuit recently observed in reversing a district court’s preliminary injunction against

elections for the Louisiana Supreme Court:

We are cognizant, however, that “‘[t]he possibility that . . . other corrective relief will

be available at a later date, in the ordinary course of litigation, weighs heavily against

a claim of irreparable harm.’” Sampson v. Murray, 415 U.S. 61, 70, 94 S. Ct. 937,

943,39 L. Ed. 2d 166 (1974) (quoting Virginia Petroleum Jobbers Assn. v. FPC, 104

U.S. App. D.C. 106, 110, 259 F.2d 921, 925 (1958)). In this we agree with the

commentators who suggest that “[o]nly when the threatened harm would impair the

court’s ability to grant an effective remedy is there really a need for preliminary

relief.” Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure § 2948 at 431-34 (1973).

Chisom v. Roemer, 853 F.2d 1186, 1189 (5th Cir. 1988).

Harm is only irreparable when it cannot be redressed by a legal or an equitable remedy

following a trial. See e.g. Weinberger v. Romero-Barcelo, 456 U.S.305,312,102 S. Ct. 1798, 1803,

72 L. Ed. 2d 91, 98 (1982) (“The Court has repeatedly held that the basis for injunctive relief in the

federal courts has always been irreparable injury and the inadequacy of legal remedies.”) See also

Goosby v. Town of Hempstead, 981 F. Supp. 751, 763 (E.D.N.Y. 1997) (preliminary injunction to

stop election denied because any injury plaintiff would suffer could be remedied after trial). The

Court should refuse to enjoin the election in progress on the grounds that the plaintiffs have failed

to show they will suffer irreparable injury if the injunction does not issue.

11

III. STOPPING THE CONGRESSIONAL ELECTIONS PROCESS WOULD CAUSE

SUBSTANTIAL AND IRREPARABLE HARM TO THE PUBLIC AND

DEFENDANTS.

Plaintiffs unpersuasively argue that no harm can result to the defendants and the public if

their motion is granted.!" Remarkably, plaintiffs never discuss the inevitable, irreparable and

deleterious consequences of awarding them the relief they seek. Plaintiffs contend that the

extraordinary remedy of enjoining the ongoing congressional election is appropriate for the purpose

of putting candidates “on notice” to minimize their campaigning and to “alert” the General Assembly

to the need to prepare “a contingency redistricting plan to be put into effect in the event that the

preliminary injunction was made permanent.” See Plaintiffs’ Brief in Support of Motion for

Preliminary Injunction at 7-8. This indeed would be an extraordinary use of the Court’s injunctive

powers. Plaintiffs have delayed far too long. Voting has begun, campaigning is in full swing and

campaign contributions have been made and spent. Both the defendants and the public interest will

be irreparably harmed if the Court does not deny the motion for preliminary injunction and allow

the election process to move forward. In an election context, the defendants’ interest in proceeding

with elections is inextricably linked to the public interest in going forward. “The election has been

scheduled as required by state law and any election is, without question, in the public interest.”

LeBlanc-Sternberg v. Fletcher, 763 F. Supp. 1246, 1249 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

H In the elections context, the harm to defendants and the public are inextricably

intertwined and thus will be reviewed together. See LeBlanc-Steinberg v. Fletcher, 763 F. Supp.

1246, 1249 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

12

A. UNWARRANTED DELAY BY PLAINTIFFS.

Plaintiffs have sat on their rights to the detriment of the citizens of North Carolina. They

filed their first complaint in this case over eighteen months ago and declined to participate in the

remedial proceedings in Shaw when the 1997 plan was approved as an adequate remedy of the

constitutional violation, even though they had joined that case as plaintiffs. They filed their

amended complaint in this case on October 17, 1997, with a prayer for both a temporary restraining

order and preliminary injunction to enjoin preparations for primary or general elections. However,

they delayed thereafter for three and one-half months, until January 30, 1998, on the eve of the

closing of the candidate filing period, before filing an unsupported motion for preliminary

injunction. They finally filed a brief in support of their motion for preliminary injunction on

February 23, 1998.

In cases involving allegedly unconstitutional apportionment, courts are to fashion relief

according to the “well-known principles of equity.” Reynolds, 377 U.S. at 585, 84 S. Ct. at 1394,

12 L. Ed. 2d at 544. This equitable doctrine is supported by sound principles of judicial and public

policy that operate independently of the merits of plaintiffs’ claims, recognizing that an unexcused

delay in prosecuting a claim, whether through simple neglect or intentional abuse of process, can

prejudice the rights not only of specific defendants but, of those unnamed who would be affected

by tardy adjudication of the claim. In the present case, such prejudice would reach all voting citizens

of North Carolina and candidates for the 1998 congressional elections.

The failure to exercise an enforceable right for an unreasonable amount of time may bar both

equitable and legal relief. Goshen Road Environmental Action v. United States Dept. of Agriculture,

891 F. Supp. 1126, 1132 (E.D.N.C. 1995), aff'd 103 F.3d 117 (4th Cir. 1996). When a party seeks

13

injunctive relief, unexplained delay standing alone may justify denial of a preliminary injunction.

Tough Traveler, Ltd. v. Outbound Products, 60 F.3d 964, 968 (2nd Cir. 1993); Majorica, S.A. v. R.H.

Macy & Co., 762 F.2d 7, 8 (2nd Cir. 1985). In such cases, plaintiffs’ argument of irreparable injury

is negated by their delay in moving for a preliminary injunction. Tough Traveler, 60 F.3d at 968

(presumption of irreparable harm is inoperative if plaintiff has delayed in moving for preliminary

injunctive relief); Citibank, N.A., 756 F.2d at 276 (“delay may not rise to the level of laches and

thereby bar a permanent injunction,” but still indicates an absence “of irreparable harm required to

support a preliminary injunction”); Majorica, S.A., 762 F.2d at 8 (lack of diligence may preclude

preliminary injunction because it goes to issue of irreparable harm).

Plaintiffs’ challenge to the 1997 Congressional plan could have been resolved on the merits

during the months that have elapsed since the complaint was amended in October, 1997. Under

these circumstances, denial of preliminary injunctive relief is justified since the “potential harm was

a product of [plaintiffs’Jown delay.” Quince Orchard Valley Citizens Ass 'n., Inc. v. Hodel, 872 F.2d

75, 79 (4th Cir. 1989). In Quince Orchard Valley, the court cautioned that equity demands those

who would challenge “time sensitive” public matters should do so with “haste and dispatch.” 7d.

at 80. See also Skehan v. Board of Trustees of Bloomsburg State College, 353 F. Supp. 542, 543

(M.D. Pa. 1973) (“Since an application for preliminary injunction is based upon an urgent need for

the protection of Plaintiffs’ rights, a long delay in seeking relief indicates speedy action is not

required.”).

There is no explanation that can excuse plaintiffs’ procrastinationin this case at the expense

of the voting public. Inexcusable or unreasonable delay in challenging a voting plan occurs after

“the plaintiff discovers or with reasonable diligence could have discovered” the facts giving rise to

14

the litigation. White v. Daniel, 909 F.2d 99, 102 (4th Cir. 1990). A delay of as little as a few

months can be inexcusable. See Citizens for the Scenic Severn River Bridge, Inc. v. Skinner, 802 F.

Supp. 1325, 1342 (D. Md. 1991), aff'd, 972 F.2d 338 (4th Cir. 1992) (delay of approximately ten

months); Libertarian Party v. Davis, 601 F. Supp. 522, 525 (E.D. Ky. 1985) (delay of three months

from constructive knowledge and one and one-half months from actual knowledge); Dobson v.

Mayor & City Council of Baltimore City, 330 F. Supp. 1290, 1301-02 (D. Md. 1971) (delay of three

and one-half months). With the election process set to begin, plaintiffs’ lack of diligence in moving

for a preliminary injunction is inexcusable and unreasonable. It is well established that any claim

against a state electoral procedure must be expressed expeditiously. E.g., Williams v. Rhodes, 393

U.S. 23, 34-35, 89 S. Ct. 5,12, 21 L. Ed. 2d 24, 33-34 (1968); Fulani v. Hogsett, 917 F.2d 1028,

1031 (7th Cir. 1990). The dalliance by plaintiffs in such an important matter is unexplained and

inexplicable; they are entitled to no relief in equity.

In two election cases indistinguishable from the facts of the case at bar, a motion for

preliminary injunction to halt an election was denied on the equitable grounds of laches. In one case,

relief was denied where plaintiffs filed suit two and one-half months prior to the election, but did not

seek an injunction until three weeks prior to the election. McNeil v. Springfield Park Dist., 656 F.

Supp. 1200 (C.D. 111. 1987). In McNeil, the court specifically noted that candidates had commenced

campaigning in earnest and had expended both time and money in their election efforts; furthermore,

the election machinery had been placed in motion and absentee balloting had begun. Id. at 1201-2,

1203. Plaintiffs’ failure to seek an injunction until immediately prior to the election when the facts

giving rise to the cause of action were known at the time the suit was filed, was “inexcusable delay.”

Id. at 1203. Similarly, the district court in Knox v. Milwaukee County Bd. of Elections Comm rs,

13

581 F. Supp. 399 (E.D. Wis. 1984), held that an attempt to enjoin an upcoming primary was barred

by laches when the suit and injunction request were filed only seven weeks prior to the election. In

Knox, the court found that an injunction “would have a devasting impact on the electoral process”

since the campaign had been underway for nearly two months.

In this regard candidates’ election reports have been filed, campaign committees

organized, contributions solicited, and literature distributed. In addition, the

Milwaukee County Board of Election Commissioners has itself prepared absentee

ballots, distributed informational publications and notices, and undertaken to comply

with the myriad of other election requirements prescribed by state law. An order

enjoining the elections at this late date would thus result in considerable prejudice to

the defendants, the candidates, and the electorate itself.

Id. at 405.

Substantial prejudice is apparent here, where the election machinery is in progress and votes

are being cast. The primary election is only six weeks away. In determining whether prejudice

exists, courts “assume that considerable voter confusion would result when citizens [find] themselves

no longer in the same [congressional] district, and likely faced with choosing from unfamiliar

candidates for [congressional]seats.” Simkins v. Gressette, 495 F. Supp. 1075, 1081 (D.S.C.), aff d,

631 F.2d 287 (4th Cir. 1980). Here, the assumption is fully justified. Candidates have filed and are

actively campaigning; ballots have been prepared and voting has begun. Citizens, candidates and

election administratorshave settled expectations regarding the boundaries of the challenged districts.

The voters of North Carolina have a clear interest in knowing in which districts they reside and in

having an adequate opportunity to consider the qualification of candidates seeking to represent

particular districts in the imminent elections. '?

i See generally, Second Bartlett Aff; Jones Aff.; Myrick Aff; Taylor Aff; Clayton

Aff; Etheridge Aff; and Price Aff.

16

Defendants cannot conceive of, and plaintiffs have not proposed, a rational plan if the

ongoing election is enjoined that would not significantly prejudice North Carolina voters as well as

crucial public policies preserved through the existing election timetables. The present case offers

a “classic instance” exemplifying the wisdom of equitable forbearance. See, e.g., Simkins, 631 F.2d

at 295-96 (citing “enormous disruption” to voters, candidates, and electoral process from plaintiffs’

delay in petitioning for reapportionment); Fulani, 917 F.2d at 1031 (*As time passes, the state’s

interest in proceeding with the election increases in importance as resources are committed and

irrevocable decisions are made.”). The harm to the public and the defendants if the ongoing election

is enjoined is palpable, and results entirely from plaintiffs’ delay in seeking relief. Equity demands

that plaintiffs’ request be denied.

B. Low VOTER TURNOUT.

The public interest dictates that the congressional primaries be held at the same time as

primary elections for other offices. “Otherwise, low voter turnout might well occur.” Republican

Party of Va., 774 F. Supp. at 407. Low voter turnout is a critical factor causing courts to be very

reluctant to require that elections be postponed and held separately from other scheduled elections.

See, e.g., Watkins v. Mabus, 771 F. Supp. 789, 801 (S.D. Miss. 1991) (three-judge court), aff'd in

part, vacated in part, 502 U.S.954,112S. Ct. 412,116 L. Ed. 2d 433 (1991) (vacated only as to part

of appeal relating to § 5 of the Voting Rights Act, on grounds of mootness); Campos v. City of

Houston, 776 F. Supp. 304, 308 (S.D. Tex. 1991); Cosner v. Dalton, 522 F. Supp. 350, 363-64 (E.D.

Va. 1981). Past experience in North Carolina demonstrates that a separate primary election for the

17

congressional races in North Carolina will produce a substantially reduced turnout.” Postponing the

congressional primary and holding it separately would cause such a depressed turnout as to deprive

the voters and citizens of this State of a meaningful process for selecting congressional candidates.

The Court’s “overriding concern” should be “to avoid a disruption of the electoral process, an event

which would materially adversely affect racial . . . minorities.” Terrazas v. Clements, 537 F. Supp.

514, 546-47 (N.D. Tex. 1982) (three-judge court).

C. DISRUPTION OF ELECTION PROCESS, COSTS AND ADMINISTRATIVE BURDENS.

The election machinery and its administration is a multi-phased and lengthy process from

the time the candidate filing period opens until the election itself. The recognized harm to the public

in enjoining an election already begun clearly weighs against the entry of a preliminary injunction

halting North Carolina’s congressional elections.

In considering injunctive relief, the Court must keep in mind what would be required if

elections under the 1997 plan are enjoined. This Court may not simply adopt a new plan, but would

be required to give the General Assembly the first opportunity to draft a new plan, see McDaniel v.

Mehfoud, 702 F. Supp. 588, 596 (E.D. Va. 1988); Cosner, 522 F. Supp. at 364, and the plan would

have to be precleared by the U.S. Department of Justice before it could be implemented. See

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130, 153, 101 S. Ct. 2224, 2228, 68 L. Ed. 2d 724, 742-43 (1981).

No viable means of adopting a new plan and conducting orderly congressional elections

exists. Even putting an interim court-ordered plan into effect at this late date would be no quick and

easy task. It would require input from the parties and the public, and development of criteria to be

i See Second Bartlett Aff. § 11; Jones Aff. 4 6; Myrick Aff. § 6; Taylor Aff. | 6;

Clayton Aff. § 11; Etheridge Aff. § 9; and Price Aff. 9 10.

18

used in drawing a court-created plan. See Watkins, 771 F. Supp. at 799. In Watkins, the three-judge

court noted that even a court-developed interim plan would not be practicable when the court was

issuing its opinion only three days before the candidate qualifying deadline, a date which already has

passed for this election.

Allowing elections to proceed in an orderly and timely manner is so important an interest of

the public that courts often allow elections to proceed even under plans which have already been

held unconstitutional or which are otherwise invalid.!* The logistics and timing of establishing a

new plan and election schedule compel the courts to allow defendants to proceed with imminent

election proceedings except under the most extraordinary circumstances. In Cosner, a three-judge

court allowed Virginia's 1981 legislative elections to proceed under a plan which it declared

unconstitutional. “Certification of candidates, ballot preparation, and a host of other election

mechanics must be undertaken promptly if the existing schedule is to be followed.” 522 F. Supp.

at 363. The court held the state’s plan unconstitutional and denied preliminary injunctive relief in

the same decision, issued only two weeks after the plan’s enactment. In another case, a court

allowed an election to go forward even under a plan which had been denied preclearance by the U.S.

Attorney General because “[t]he election is imminent, absentee balloting is scheduled to begin in

i As noted by the court in French v. Boner, 771 F. Supp. 896, 902, n.8 (M.D. Tenn.

1991), “other courts have withheld immediate injunctive or other equitable relief that would have

affected an impending election” (citing Chisom, 853 F.2d at 1192; Simkins, 631 F.2d at 295-296;

Maryland Citizens for a Representative Gen. Assembly v. Governor of Md., 429 F.2d 606, 609-611

(4th Cir. 1970); Banks v. Board of Educ. of Peoria, School Dist. No. 150, 659 F. Supp. 394, 398-403

(C.D. IL. 1987); Dillardv. Crenshaw County, 640 F. Supp. 1347, 1361-1363 (M.D. Ala. 1986); Mac

Govern, 637 F. Supp. at 115-116; Knox v. Milwaukee County Bd. of Elections Comm'rs, 581 F.

Supp. at 405; Martin v. Venables, 401 F. Supp. 611, 620-621 (D. Conn. 1975); and Dobson, 330 F.

Supp. at 1299-1302).

19

four days, and the county and city’s election machinery is in progress.” Campos, 776 F. Supp. at

307. Since “any change in the electoral scheme” at that point “would necessitate a separate city

election at considerable expense to the City,” the election was allowed to proceed under the

unprecleared plan as an interim measure. /d. at 308. Similarly, a three-judge district court in Texas

noted that it did not have time to draw a new legislative plan for the State of Texas, even one to be

used on an interim basis. between the end of January and March 12, 1982, the last date on which the

filing could be closed if elections were to be conducted on schedule. Accordingly. in order to permit

the legislative elections to go forward on a timely basis. the court adopted legislative districts

modified only slightly from ones for which the Attorney General had denied preclearance. Terrazas,

537 F. Supp. 514. Similar time constraints exist in North Carolina if the primary is to go forward

May 35, 1998, as scheduled.

The Supreme Court has cautioned that district courts in awarding or withholding relief should

consider the proximity of the forthcoming election and must

endeavor to avoid a disruption of the election process which might result from

requiring precipitate changes that could make unreasonable or embarrassing demands

on a State in adjusting to the requirements of the court’s decree.

Reynolds, 377 U.S. at 585,84 S. Ct. at 1394,12 L. Ed. 2d at 541. A three-judge court in this Circuit

recently recognized that granting a preliminary injunctionin a suit challenging Virginia’s legislative

redistricting plan would cause irreparable harm to the defendants in the expense and labor involved

in reconvening the General Assembly and in the disruption of the statewide election schedule.

Republican Party of Va., 774 F. Supp. at 403. See also Watkins, 771 F. Supp. at 801 (“Conducting

special elections. . . would lead to a lower voter turnout and extra expense for the State.”); Campos,

20

776 F. Supp. at 308 (goal to “minimize . . . taxpayer cost” resulting from separate election one of

several concerns which “would be thwarted by” postponement of the scheduled election).

Preparations for the upcoming election began shortly after adoption and approval of the

current plan and have proceeded apace. County boards of elections updated their precinct records;

voters were informed of their new districts; the candidate filing period opened and closed; first notice

of the primary election and registration deadline wis published; ballots were designed, printed and

distributed; voting, by absentee ballot, began.” The election process is moving inexorably to

conclusion. The Courts have recognized as valid considerations that the impending elections are

imminent, the election machinery is already in progress, and the election staff is readying the

precincts. French v. Boner, 771 F. Supp. 896, 902-903 (M.D. Tenn. 1991). Equity requires the

Court’s forbearance from “interfer[ing] with the conduct of rapidly upcoming elections where the

election machinery is already in gear.” Mac Govern, 637 F. Supp. at 115.

At this point in time, it is too late to draw new congressional districts and hold the scheduled

congressional primary on May 5, 1998. If the ballots cannot be ready and the congressional primary

cannot be held with all other primaries in 1998, past experience indicates that a separate

congressional primary would cost the State millions of dollars.'® The expense and labor entailed in

planning and administering a new election schedule compel denial of plaintiffs’ request for a pre-

liminary injunction.

15 See Second Bartlett Aff. 992, 4, 5, 7 and 9.

Ie See Second Bartlett Aff. 12.

21

D. VOTER CONFUSION AND CANDIDATE BURDEN.

Any attempt to provide for an election under new districts at this date could only engender

confusion and problems inconsistent with the goal of allowing North Carolina’s voters to elect

congresspersons of their choice. Thirty-one candidates have filed and are already campaigning;

(19 contested primaries are being conducted in eight districts.” “[T]he public interest favors an

electorate familiar with its candidates. . . . [A] rush to reorganize can only increase confusion

brought about by redistricting.” Republican Party of Va., 774 F. Supp. at 407. “The impending. . .

elections are imminent, and the election machinery is already in progress. The candidates have

qualified and are campaigning, the voters are preparing to make their choices and the election staff

is readying the precincts.” The Supreme Court has indicated that these are valid considerations. See

Reynolds, 377 U.S. at 585, 84 S. Ct. at 1393-94, 12 L. Ed. 2d at 541.

Courts may also consider the impact of enjoining an upcoming election on the candidates

who have already invested time and money in campaigning under the existing plan and schedule.

See Maryland Citizens for a Representative Gen. Assembly v. Governor of Md., 429 F.2d 606 (4th

Cir. 1970); Banks v. Board of Educ. of Peoria, School Dist. No. 150, 659 F. Supp. 394 (C.D. Ill.

1987); Dobson, 330 F. Supp. 1290. Six incumbent candidates (three Republicans and three

Democrats), who are experienced with the frontline mechanics of organizing, fundraising and

campaigning for election, have filed affidavits expressing concern that enjoining the election would

be confusing to the public and would not allow voters an adequate opportunity to learn about their

H See Second Bartlett Aff. 3.

22

new districts or to become familiar with the candidates.'!® All of the time. energy, money and effort

already expended by the candidates and their supporters will be unnecessarily wasted if the election

is halted at this late stage. The year-end financial reports of the congressional candidates (covering

the period from July, 1997, when the new plan was enacted, through December, 1997) show that

over three million dollars already had been contributed and more than one and one-half million

dollars had been spent by the time plaintiffs filed their motion for preliminary injunction.” It is far

too late to put the candidates “on notice,” as suggested by plaintiffs, that they should limit, minimize

or put on hold their electioneering efforts. Compromising the election process in this manner is

precisely the evil courts seek to avoid by refusing to enjoin ongoing elections. Furthermore,

attempting to substitute a different plan “would not give candidates enough time to decide whether

to run; it would not give those charged with elections enough time to prepare; and it would not give

voters adequate opportunity to familiarize themselves with their districts and their candidates.”

Watkins, 771 E. Supp. at 801.%

Disruption to other elections would also occur if a new congressional plan was put into place

with a new filing period and separate election. Filing for local, state and congressional offices

normally takes place all at the same time. Filing for local and state legislative offices has now

13 See Jones Aff. 99 4 and 7; Myrick Aff. 14, 6 and 7; Taylor Aff. 1] 4, 6 and 7;

Clayton Aff. 9 8 and 10; Etheridge Aff. 17, 9 and 10; and Price Aff. {9 and 11.

i See Second Bartlett Aff. § 13.

i See also Second Bartlett Aff. 9 8 and 9; Jones Aff. 19 4 and 7; Myrick Aff. 14 and

6; Taylor Aff. 9] 4 and 6; Clayton Aff. 99 8-10; Etheridge Aft. 177 and 9; and Price Aff. 7 8 and

9,

closed.’ The pool of potential candidates for congressional office is made up in large part of people

who are potential candidates for state and local offices. If a new and separate filing period is opened

for congressional elections, some persons who have already filed for local or state offices might be

tempted to refile for one of the newly designed congressional seats. This would disrupt the state and

local primaries with candidates abandoning those races remaining on those ballots, while new

candidates for state and local offices could not enter those races.”> The converse of this problem is

that potential candidates who have already foregone filing or refiling for state or local offices in

order to run for Congress, may find the newly created districts unfavorable to them, but they are

foreclosed now from entering state and local races.”

“Elections are for the voters; it is their opportunity to elect their representatives. . ..” Any

concerns of the court about the plan “are far outweighed by the benefits to the voters in these

elections.” Watkins, 771 F. Supp. at 804. “Holding the election on a timely basis will result in the

highest possible voter turnout, the least voter confusion, and a savings to the” State, making adher-

ence to the existing plan and schedule by far “the best option available” to the Court and to the

citizens of North Carolina. Campos, 776 F. Supp. at 308. If an invalid plan may be employed to

accomplish this purpose, as has been done so often, then clearly North Carolina’s 1997

2 See Second Bartlett Aff. § 2.

22 Because of this same potential harm, in 1992, when the state’s redistricting plans

were not precleared and it was necessary to delay the opening and closing of candidate filings for

the State House, State Senate and Congress for a short time, the General Assembly delayed candidate

filing deadlines for all partisan primaries. 1991 N.C. Sess. Laws, Extra Sess., ch. 1.

3 For example, the Court may take judicial notice that Representative Linwood E.

Mercer and Senator Daniel E. Page did not file for re-election to the North Carolina General

Assembly in order to run for Congress.

24

Congressional redistricting plan, “not presently held invalid, should be accorded the same

treatment.” Republican Party of Va., 774 F. Supp. at 407.

IV. PLAINTIFFS CANNOT SHOW A LIKELIHOOD OF SUCCESS ON THE MERITS.

Since the plaintiffs in this case cannot show that possible harm to them “decidedly”

outweighs the harm to the defendants, they must convince the Court of a significant likelihood that

they will prevail. “As the balance [of harm] tips away from the plaintiff, a stronger showing on the

merits is required.” Direx Israel, 952 F.2d at 813. In this case plaintiffs have not, and indeed

cannot, meet their burden to show they are likely to succeed on the merits of their claim. As already

set out in Defendants’ Brief in Opposition to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment and in

Support of Their Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment, North Carolina’s 1997

Congressional redistricting plan is a lawful exercise of the discretionary powers of the General

Assembly.?* The undisputed material facts establish that the 1997 plan lacks the earmarks of an

unconstitutionalracial gerrymander. Furthermore, race was not the predominate factor motivating

the legislature’sdecisions in drawing challenged Districts 1 and 12, and traditional districting criteria

were not subordinated to race.

The Supreme Court has placed a heavy burden of proof on plaintiffs asserting a claim of

racial gerrymandering. Proof that race was “a motivation for drawing of a majority-minority

district,” that “redistricting is performed with consciousness of race,” or that “traditional districting

criteria” were “neglected” are not sufficient to meet the plaintiffs’ burden. Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S.

2 Defendants will not repeat here the factual statement of the case and legal arguments

they made in their summary judgment brief, which the defendants incorporate herein by reference,

but will simply highlight points relevant to the preliminary injunction inquiry.

25

932, ,1168. Ct. 1941,1952-33, 135 L. Ed. 2d 243, 257-59 (1996) (emphasis in original).

Plaintiffs’ reliance on little more than a “fruit of the poisonous tree” theory and the racial

composition of certain districts cannot withstand defendants’ summary judgment motion and

certainly fails to establish a likelihood of success on the merits.

The gravamen of plaintiffs’ complaint is their aversion to the 1992 plan. They are not

satisfied solely with remedying the unconstitutional features of that plan, but seek to obliterate all

traces of Districts 1 and 12. The Supreme Court has made quite clear, however, that federal court

review of districting legislation “represents a serious intrusion on the most vital of local functions”

and has admonished the lower courts “to exercise shelnninory caution in adjudicating claims that

a state has drawn district lines on the basis of race.” Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. _, 1158S.

Ct. 2475, 2488, 132 L. Ed. 2d 762, 779 (1995). Thus, in reviewing the State’s 1997 plan, “the

discretion of the federal court is limited except to the extent the plan itself runs afoul of federal

law.” Lawyer v. Departmentiof Justice, 521 U.S. = .117:8.Ct.2186,2193, 138 L.Ed. 2d

669, 680 (1997).

The 1997 plan is supported by a new legislative record separate from the 1992 legislative

record. It was proposed by new congressional redistricting committees and enacted by a different

General Assembly. The 1997 plan reflects the current legislature’s different goals and eliminates

the earmarks of a racial gerrymander. Under these circumstancesthe Court is limited to determining

“whether the proffered remedial plan is legally unacceptable because it violates anew constitutional

or statutory voting rights -- that is, whether it fails to meet the same standards applicable to an

original challenge of a legislative plan in place. Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S.37,42,102 S. Ct. 1518,

1521, 71 L. Ed. 2d 725 (1982).” McGhee v. Granville County, N.C., 860 F.2d 110, 115 (4th Cir.

26

1988). Plaintiffs’ complaints about the 1992 plan and its elected representatives are irrelevant to

this Court’s current inquiry and are insufficient to establish a claim against the 1997 plan.

Similarly, plaintiffs’ reliance on the racial demographics of the challenged districts is

unavailing. “If district lines merely correlate with race because they are drawn on the basis of

political affiliation, which correlates with race, there is no racial classification to justify.” Bush v.

Vera, 116 S. Ct. at 1956, 135 L. Ed. 2d at 263. District 12 separates Democratic voters from a sea

of Republican voters.” The “law does not condemn political partisanship,” even in a majority-

minority district, as unlawful racial gerrymandering. Moon v. Meadows, 952 F. Supp. 1141, 1148

(E.D. Va. 1997). With respect to District 1, plaintiffs concede that this district in the state’s

northeastern region has historic and demographic legitimacy. This district encompasses a

geographically compact and politically cohesive concentration of African-Americans whose

preferred candidates historically have been defeated by the white majority voting as a bloc.”

Plaintiffs’ theory that a 50.27% African-American total population majority constitutes an

unnecessary ‘“over-concentration” of minority voters is no more than uninformed speculation

unsupported by fact or law.

CONCLUSION

The State’s 1998 congressional elections should not be disrupted based on an uncertain cause

of action alleging possible theoretical harm to a handful of voters from two districts, compared to

the greater harm to the other more than six million citizens of the State of North Carolina should the

2 See Cooper Aff. 9 14; Peterson Aff. 9 3 and 21.

i See Bartlett Aff., Vol. IV at 97C-28F-3B, Witness Statements, Tab. 2, Expert Rpt.

of Dr. Engstrom, pp. 4-21 and 27-28; Vol. V at 97C-28F-4D(3), Att. 4.

27

upcoming election be postponed. The State of North Carolina should be allowed to get on with the

business of electing its congressional representatives without unwarranted interference by the federal

courts.

This the 20th day of March, 1998.

MICHAEL F. EASLEY

ATTORNEY GENERAL

(—

Edwin M. Speas, Jr.

Senior Deputy Attorney General

N.C. State Bar No. 4112

A

Tiare B. Smiley

Special Deputy Attorney General

N. C. State Bar No. 7119

Norma S. Horal

Special Deputy Attorney a

N.C. State Bar No. 6654

N.C. Department of Justice

P.O. Box 629

Raleigh, N.C. 27602

(919) 716-6900

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that I have this day served a copy of the foregoing Defendants’ Brief In

Opposition To Motion For Preliminary Injunction and the Affidavits of Congresspersons

Walter B. Jones, Sue Myrick, Charles H. Taylor, Eva M. Clayton, Bob Etheridge and David

E. Price, and Second Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett in the above captioned case upon all parties

by depositing these documents in the United States mail, first class mail, postage prepaid addressed

as follows:

Robinson O. Everett

Suite 300 First Union Natl. Bank Bldg.

301 W. Main Street

P.O. Box 586

Durham, NC 27702

Martin B McGee

Williams Boger Grady Davis & Tittle PA

Post Office Box 810

Concord NC 28026-0810

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

Anita S. Hodgkiss

Ferguson, Stein, Wallas, Adkins.

Gresham & Sumter, P.A.

741 Kenilworth Avenue

Charlotte, NC 28204

ATTORNEYS FOR APPLICANTS FOR INTERVENTION

This the 20th day of March, 1998.

\

il 5. Lior

Z

TE Smiley I

Special Deputy Attorney Genera

20

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

EASTERN DIVISION

Civil Action No. 4-96-CV-104-BO(3)

MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS )

CHANDLER MUSE, and GLENNES )

DODGE WEEKS,

Plaintiffs,

V.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official

capacity as Governor of the State of North

Carolina, et al.,

Defendants.

AFFIDAVITS FILED BY DEFENDANTS

RELATING TO SUMMARY JUDGMENT

AND PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION PROCEEDINGS

5

SENATOR ROY A. COOPER, III

REPRESENTATIVE W. EDWIN M'MAHAN

DR. DAVID R. GOLDFIELD

DR. DAVID W. PETERSON

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

EASTERN DIVISION

Civil Action No. 4-96-CV-104-BO(3)

MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS )

CHANDLER MUSE, and GLENNES )

DODGE WEEKS.

Plaintiffs,

V.

AFFIDAVIT OF

JAMES B. HUNT. JR, in his official ROY A. COOPER, III

capacity as Governor of the State of North

Carolina. et al.,

Defendants.

Roy A. Cooper, III, being first duly sworn deposes and says:

5 [ am a native of Nash County, North Carolina. After receiving my undergraduateand

law degrees from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I returned home to Nash County

where I have practiced law since 1982. A copy of my resume is attached to this affidavit.

2 In 1986, 1988 and 1990, 1 was elected to the North Carolina House of Representatives

and in 1992, 1994 and 1996, I was elected to the North Carolina Senate. During the 1996 Session

of the General Assembly, I served as Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee and the Senate

Select Committee on Congressional Redistricting. I had not previously served on any redistricting

committee.

3. My responsibility as Chairman of the Senate Redistricting Committee was to attempt

to develop a new congressional plan that would cure the constitutional defects in the prior plan, and

that would have the support of a majority of the members of the Senate. which was controlled by the

Democrats. and the support of a majority of the members of the House. which was controlled by the

Republicans. Under an order entered by the three-judge court in Shaw v. Hunt. the new plan had to

be completed by March 31, 1997, to avoid the federal court imposing a plan on the State. The

Senate's efforts to meet this responsibility are recorded in the transcripts of the meetings of the

Senate Committee and of the debates on the floor of the Senate. A true and accurate copy of these

transcripts is included in the North Carolina Section 5 Submission. 1997 Congressional Redistricting

Plan (filed with the Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett) as Attachments 97C-28F-4D(1)-(4).

4. Representative W. Edwin McMahan was appointed Chairman of the House

Redistricting Committee by Speaker Brubaker. His responsibilities were essentially identical to

mine.

s. Many people doubted that the General Assembly would be able to achieve a

compromise between the Democratic controlled Senate and Republican controlled House.

Redistricting generally is a task which becomes extremely partisan. Working with the leadership

of the Senate and the House, however, Representative McMahan and I early on identified a single

path by which a compromise might be reached and a new plan adopted. This path was to crafta plan

which would cure the defects in the old plan and at the same time preserve the existing partisan

balance in the State’s congressional delegation. The Senate Redistricting Committee made the first

attempt to travel down this path.

6. On February 20, 1997, after consultation with other Senate members, I presented a

proposed plan, entitled Congressional Plan A (hereinafter Plan A), to the Senate Redistricting

Committee. This plan was similar to alternative plans later proposed by the House Redistricting

2

Committee and Representative McMahan and to the plan ultimately enacted by the General

Assembly. Because Plan A turned out to be the prototype for the enacted plan. I will describe the

goals the Senate leadership and I wanted to achieve in designing this plan. In addition, I will

describe the process used to draw the districts in Plan A to achieve those goals. Particular attention

will be given to Districts 1 and 12.

7 We had two goals for the plan as a whole. The first goal was to cure the

constitutional defects in the prior plan by assuring that race was not the predominate factor in

constructing any district in the plan and to assure that traditional redistricting criteria were not

subordinated to race. To accomplish this first goal, emphasis was placed on the following factors

in constructing the plan: (1) avoidance of division of precincts; (2) avoidance of the division of

counties when reasonably possible: (3) functional compactness (grouping together citizens of like

interests and needs); (4) avoidance of long narrow corridors connecting concentrations of minority

citizens; and (5) ease of communication among voters and their representatives. A comparison of

the unconstitutional 1992 plan and Plan A demonstrates that this goal was accomplished. For

example: (1) the unconstitutional plan divided 80 precincts while Plan A divided only 2 precincts

(both of which were divided only to accommodate peculiar local circumstances); (2) the

unconstitutional plan divided 44 counties while Plan A divided only 22; (3) the unconstitutional plan

divided 7 counties among 3 districts while Plan A did not divide any county among 3 districts; (4)

the unconstitutional plan used “cross-overs,” “double cross-overs” and “points of contiguity” to

create contiguous districts while Plan A used none of these devices.

8. Our second goal, and the goal that made it possible for the General Assembly to agree

upon and enact a new plan, was to maintain the existing partisan balance in the State’s congressional

~

J

delegation, 6 Republicans and 6 Democrats. Based on my discussions with Senate leaders and with

Representative McMahan. I knew that any plan which gave an advantage to Democrats faced certain

defeat in the House while any plan which gave an advantage to Republicans faced certain defeat in

the Senate. Preserving the existing partisan balance, therefore, was the only means by which the

General Assembly could enact a plan as required by the Court. To achieve this pivotal goal. we

designed Plan A to preserve the partisan core of the existing districts to the extent reasonably

possible and to avoid pitting incumbents against each other. One tool I used to measure the partisan

nature of districts was election results gathered and analyzed by the National Committee for an

Effective Congress NCEC). The NCEC information was based on the results of a series of elections

from 1990 to 1996. I also used older election results contained in the legislative computer data base.

In the end, these election results were the principal factor which determined the location and

configuration of all districts in Plan A so that a partisan balance which could pass the General

Assembly could be achieved.

3 The two goals we applied in drawing the plan as a whole were also applied in drawing

Districts 1 and 12. To assure that race did not predominate over traditional redistricting criteria,

District 12 was drawn so that (1) only 1 precinct was divided (a precinct in Mecklenburg County that

was divided in every local districting plan); (2) its length was reduced by 46% (from approximately

191 miles to 102 sition) so that it became the third shortest district in the state; (3) the number of

counties included in the district was reduced from 10 to 6; (4) all “cross-overs,” “double cross-overs”

and “points of contiguity” were eliminated; and (5) it was a functionally compact, highly urban

district joining together citizens in Charlotte and the cities of the Piedmont Urban Triad. To assure

that race did not predominate over traditional redistricting criteria, District 1 was drawn so that (1)

4

no precincts were split: (2) the number of counties included in the district was reduced from 28 to

20: (3) the number of divided counties included in the district was reduced from 18 to 10: (4) all

“cross-overs.” “double cross-overs” and “points of contiguity” were eliminated: (5) the length of the

district was reduced by 24% (from approximately 225 miles to 171 miles): and (6) it was a

functionally compact district joining together citizens in most of the rural and economically

depressed counties in the northern and central Coastal Plain region of the State.

10. Maintaining Districts 1 and 12 as Democratic leaning districts was critical to

achieving the pivotal goal of protecting the partisan balance in the State's congressional plan.

Achieving this goal for Districts 1 and 12. however, presented special problems. First. the House

insisted that District 1 had to be drawn in a manner that protected Congressman Jones in District 3

and that avoided placing Congressman Jones’ residence inside the boundaries of District 1. Second,

District 12 had to be drawn in a manner that avoided placing Congressman Burr’s and Coble’s

residences inside the boundaries of District 12. Third, District 12 had to be drawn in a manner that

would not include Cabarrus County, Congressman Hefner's home county. Fourth, significant

portions of Congressman Watt’s and Congresswoman Clayton’s former districts had been eliminated

because of the directive in Shaw v. Hunt, thus lessening their strength as incumbents. Finally, we

were concerned that Congressman Watt might lose some votes because of his race and that

Congresswoman Clayton almost certainly would lose votes because of her race. To help protect

District 1 as a Democratic leaning district, we included the heavy concentrations of Democratic

voters in the cities of Rocky Mount, Greenville, Goldsboro, Wilson and Kinston, and to help protect

District 12 as a Democratic leaning district, we included the heavy concentrations of Democratic

voters in Charlotte, Greensboro and Winston-Salem in the district.

11. In developing Congressional Plan A. I also became convinced from expert studies

before the General Assembly and my own knowledge and experience that Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act likely required the creation of a majority-minority district in the central to northern part

of the Coastal Plain. where the largest concentration of black citizens reside. See the attached map

entitled, North Carolina Counties by Percent of Population Black. which illustrates the correlation

between the boundaries of District 1 and this concentration of black citizens. That belief was

balanced with my primary goals of curing the defects in our prior plan and protecting the existing

partisan balance in the Congressional delegation in locating and drawing District 1 in Congressional

Plan A.

12. On February 20, 1997, I presented Congressional Plan A to the Senate Redistricting

Committee and on February 23, 1997, Representative McMahan presented his first plan,

Congressional Plan A. 1, to the House Redistricting Committee. Congressional Plan A and A.1 were

similar. Based on NCEC electionresults, however, I was concerned that Representative McMahan’s

plan unnecessarily diminished Democratic performance in Districts 2. 8 and 12, Congressmen

Hefner's, Etheridge’s and Watt’s districts.

13, Over the next several weeks, Representative McMahan and [ were able to resolve my

concerns and the concerns of the Senate leadership by negotiation. The compromise we reached

finally was reflected in a plan entitled “97 House/Senate Plan.” This is the plan that was enacted by

the General Assembly on March 31, 1997. The first plan, “Congressional Plan A,” and “97

House/Senate Plan,” the enacted plan, are very similar. One of the differences is that the first plan

had 24 divided counties while the enacted plan reduced the number of divided counties to 22.

14. The “97 House/Senate Plan” is a negotiated bipartisan plan which contains districts

6

located and shaped in a manner to avoid constitutional problems and to protect the existing partisan

balance in the State's Congressional delegation. Racial fairness was, of course, considered in the

development of the plan. Our obligations to represent all of our constituents of all races and to

comply with the Voting Rights Act demanded that racial fairness be considered. The plan enacted

is racially fair, but race for the sake of race was not the dominate or controlling factor in the

development or enactment of the plan. In drawing initially Congressional Plan A and in negotiating

the eventually enacted plan, partisan election data, not race. was the predominant basis for assigning

precincts to districts including precincts in Districts 1 and 12. That a large proportion of precincts

assigned to District 12 have significant black populations is simply the result of a strong Democratic

voting pattern among blacks. Moreover, District 12 is not even composed of a majority of black

citizens; it is a district in which white citizens constitute 52% of the district’s total population, 53%

of the districts’ voting age population and 54% of the districts’ registered voters. Simply, District

12 is a Democratic island in a largely Republican sea.

This the RS ey of February, 1998.

IG A lopen, TC

Roy A. Cooper, 3= 71]

Sworn to and subscribed before me this

2670. day of February, 1998.

ik lh ag

Lin ll fad

Notary Public

My commission expires: / / 2 3000

a

3

1

0

A

0

3

H

L

a

3

0150-222-008-1

“OO

A

1

d

d

N

S

T¥H3IT

I

L

V

I

S

-

1

I

V

North Carolina Counties by Percent of Population Black with 1st Congressional District Overlay

Xi

Currituck

kingham 11.25

20.39.

Dare

3.57

= 22.82 as saad hme Ban

Johnston

“37.70

Lee

22.72

Harnett

22.58

~~ Moore

Pamlico

25.95

1st District

Percent Black

0.01-4.66

466-1594

Carteret

8.34

15.94 - 25.95

25.95- 37.66

37.66-61.46

Onslow

rt ey Crested by the North Carona General Assembly Informanon Systems Division. February 24. 1998

Robeson

Age:

Occupation:

Elective

Offices:

Education:

Family:

Selected

Government

Positions:

Professional:

Selected

Civic and

Religious:

Roy A. Cooper, III

P.O. Box 4538

Rocky Mount, NC 27803-0538

(919) 442-3115

40: Born June 13, 1957

Attorney

N.C. State Senator 1991-present

N.C. House of Representatives 1987-1991

B.A., 1979 and J.D., 1982 from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Wife, Kristin and children Hilary, Natalie and Claire

Senate Majority Leader 1997-present

Current Chairman, Senate Judiciary Committee

Current Chairman, Senate Select Committee on Congressional Redistricting

Current Chairman, Senate Select Committee on Length of the Session

Current Co-Chairman, Joint Legislative Ethics Committee

Past Chairman, Senate Judiciary I/Constitution Committee

Past Chairman, Senate Judiciary II Committee

Past Chairman, Senate Economic Development Committee

Past Chairman, Select Committee on Courts

Past Chairman, Study Commission on the Juvenile Code

Past Chairman, Public Health Study Commission

Past Chairman, House Judiciary Committee

Past Chairman, Study Committee on Criminal Law

Current and past member of numerous other legislative committees, government

commissions and study committees

Managing Partner in the Law Firm of Fields & Cooper in Rocky Mount.

N.C. Bar Association: Member and CLE Instructor.

N.C. Academy of Trial Lawyers: Member and CLE Instructor.

Martindale- Hubbell “AV” rating.

Deacon in First Presbyterian Church of Rocky Mount, NC

Co-Chairman, Rocky Mount March of Dimes Chefs Auction

Board of Visitors of North Carolina Wesleyan College

Chairman, 1997-98 Rocky Mount Area United Way Campaign

Board of Directors, Visions, Inc.

Board of Directors, Tar River Chorus and Orchestra

Board of Directors, Rocky Mount American Heart Association

Honors and

Activities

while at

:

University

Activities

since

graduation:

Selected

Successful

Legislation

Introduced:

Other

Awards

and Honors:

Board of Directors, Rocky Mount Area United Way

Rocky Mount Chamber of Commerce

Member and former legal counsel of Rocky Mount Jaycees (Project Chairman

for several events)

Board of Directors of North Carolinians for Community Colleges

OIC Industrial Advisory Council

Teach for America Advisory Council

Morehead Scholar

Order of the Golden Fleece

Order of the Grail

Order of the Old Well

Dean's List

Chief Justice of Student Supreme Court

President of UNC Young Democrats

Student Government Cabinet

Chairman, Edgecombe/Nash Morehead Scholarship Selection Committee

UNC Board of Visitors

Board of Directors of UNC Law Alumni Association

Life Member, UNC General Alumni Association

Gubernatorial Veto Constitutional Amendment

Open Meetings Law

Open Public Records Law

Non-Partisan Election of Superior Court Judges Bill

Environmental Crimes Bill

No Guns in School Safety Bill

Distinguished Young Alumnus Award, UNC-Chapel Hill

Order of the Long Leaf Pine Honor Society

N.C. Jaycees Freedom Guard Award

N.C. Press Association Legislator of the Year

N.C. Academy of Trial Lawyers Legislator of the Year

N.C. Cued Speech Legislative Award

Rocky Mount Jaycees Distinguished Service Award

In 1988, selected as the "Most Effective" Freshman Representative in the N.C.

House by the non-partisan N.C. Center for Public Policy Research

In 1996, ranked as the fourth most effective Senator in the N.C. Senate by the

same organization

}

0

0

A

d

d

N

S

T

¥

O

3

T

3

L

V

L

S

=

(

d

3

7

0

A

0

3

d

LLa3

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

EASTERN DIVISION

Civil Action No. 4-96-CV-104-BO(3)

VIARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS )

CHANDLER MUSE, and GLENNES )

DODGE WEEKS.

Plaintiffs,

AFFIDAVIT OF

Ww. EDWIN MCMAHAN

V.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official

capacity as Governor of the State of North

Carolina, et al.,

Defendants.

W_ Edwin McMahan, being first duly sworn, deposes and says:

E [ am a native of Buncombe County, North Carolina and have resided in Charlotte,

North Carolina since 1974. A copy of my resume is attached.

2. In 1994 and 1996, I was elected to the North Carolina House of Representatives.

During the 1997 Session of the General Assembly, Harold J. Brubaker, Speaker of the House,

appointed me to serve as Chairman of the House Congressional Redistricting Committee. I had no

previous involvement in congressional redistricting.

3. My responsibility as Chairman of the House Redistricting Committee was to attempt

to develop a new congressional plan that would cure the constitutional defects in the prior plan, and

that would have the support of a majority of the members of the Senate, which was controlled by the

Democrats; and the support of a majority of the members of the House, which was controlled by the

Republicans. Under an order entered by the three-judge court in Shaw v. Hunt. that task had to be

completed by March 31. 1997, to avoid the federal court imposing a plan on the State.

4. Senator Roy A. Cooper. III, was appointed Chairman of the Senate Redistricting