Supreme Court Hears Argument on How Fast is "Deliberate Speed?"

Press Release

March 30, 1964

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 1. Supreme Court Hears Argument on How Fast is "Deliberate Speed?", 1964. 7fb4c1d3-b492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c64b1e87-448c-46aa-ba5b-fa89589c743c/supreme-court-hears-argument-on-how-fast-is-deliberate-speed. Accessed March 07, 2026.

Copied!

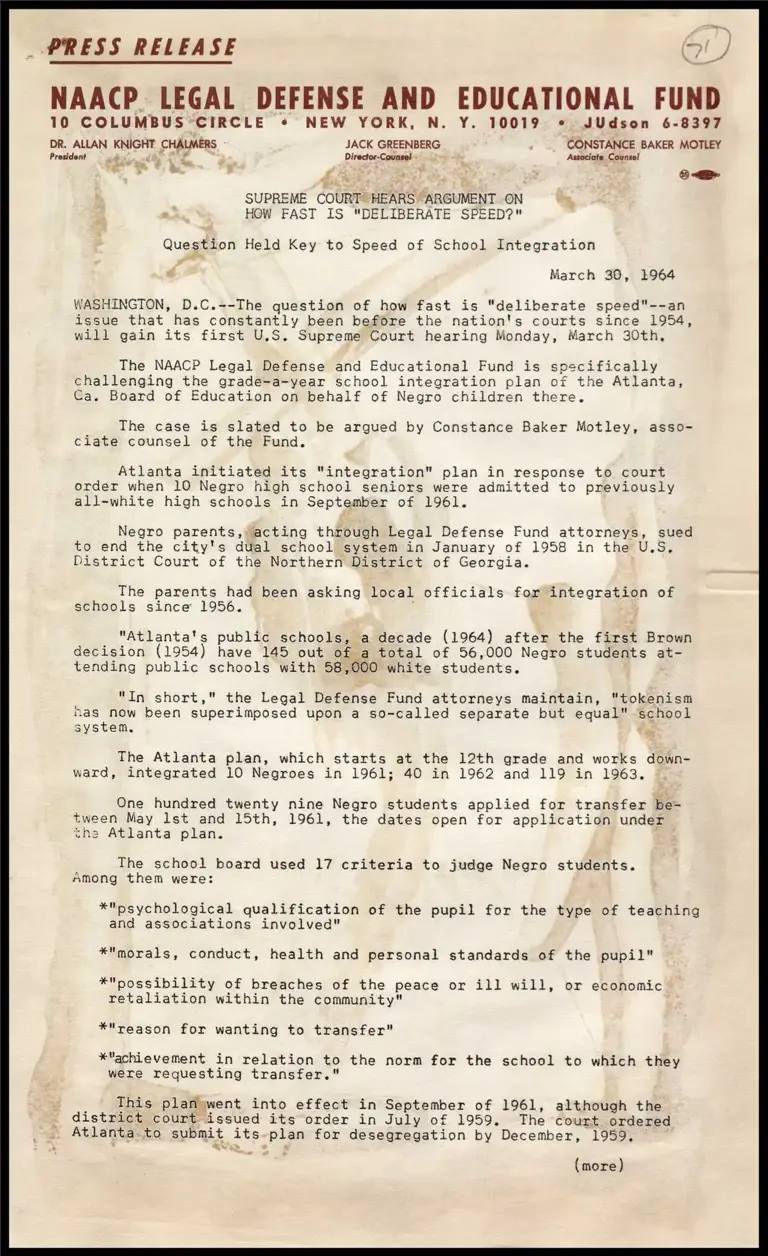

PRESS RELEASE Gr)

NAACP. LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE * NEW YORK, N. Y. 10019 * JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS JACK GREENBERG ‘ CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

President ae Tg Director-Counsel- Associate Counsel

— 7% - Lees 4 oS

SUPREME COURT HEARS “ARGUMENT ON ,

ce HOW FAST IS "DELIBERATE SPEED?"

Question Held Key to Speed of School Integration

é March 30, 1964

WASHINGTON, D.C.--The question of how fast is "deliberate speed"--an

issue that has constantly been before the nation's courts since 1954,

will gain its first U,S. Supreme Court hearing Monday, March 30th,

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund is specifically

challenging the grade-a-year school integration plan of the Atlanta,

Ga. Board of Education on behalf of Negro children there.

The case is slated to be argued by Constance Baker Motley, asso-

ciate counsel of the Fund.

Atlanta initiated its "integration" plan in response to court

order when 10 Negro high school seniors were admitted to previously

all-white high schools in September of 1961.

Negro parents, acting through Legal Defense Fund attorneys, sued

to end the city's dual school system in January of 1958 in the U.S,

District Court of the Northern District of Georgia.

The parents had been asking local officials for integration of

schools since 1956.

"Atlanta's public schools, a decade (1964) after the first Brown

decision (1954) have 145 out of a total of 56,000 Negro students at-

tending public schools with 58,000 white students.

"In short," the Legal Defense Fund attorneys maintain, "tokenism

has now been superimposed upon a so-called separate but equal" school

system, *

The Atlanta plan, which starts at the 12th grade and works down-

ward, integrated 10 Negroes in 1961; 40 in 1962 and 119 in 1963.

One hundred twenty nine Negro students applied for transfer be=

tween May lst and 15th, 1961, the dates open for application under

the Atlanta plan.

The school board used 17 criteria to judge Negro students.

Among them were:

*"psychological qualification of the pupil for the type of teaching

and associations involved"

*"morals, conduct, health and personal standards of the pupil"

*"possibility of breaches of the peace or ill will, or economic

retaliation within the community"

*"reason for wanting to transfer"

*Yachievement in relation to the norm for the school to which they

were requesting transfer."

; This plan went into effect in September of 1961, although the

district court issued its order in July of 1959. The court ordered

Atlanta. to submit its-plan for desegregation by December, 1959,

(more)

Supreme Court Hears Argument on -2- Maret 304 1968 fe

How Fast Is "Deliberate Speed?" * z

The district court said that this was cont inseae “upon enactment of

State statutes permitting such a plan to be put into. Contest ones

FY

~ Georgia had laws providing for closing or withholding state

from racially mixed schools,

The city of Atlanta waited until December 1, 1959--the final

provided by the court--to submit its integration plan.

School Board spokesmen cited numerous administrative problem:

submitting their pupil assionWagt plan with its 17 criteria. Pe

Eleven days later, Legal Def Ase Fund attorneys filed a ns too

the plan, arguing that: ,

ia as

| system *it did not end the dual sch

*Negro students would be assi on the basis of race

*the »burden of transfer was re Solely on Negro children

¥the school board had not ated the need for a 12 year

in which to accomplish i id

*the plan did not provid choo) administrativ

personnel without regan 4

The district court reje

Meanwhile, the Georgia legislature adjou without ropes a

anti-school integration laws, thereby blocking enactment of the PA

Legal Defense Fund attorneys argue that "it is painfully appar

that the plan calls fora war of attrition, in which only the har

Will be able to bear the burden of a contest with state power."

Moreover, the plan "not Mly depends upon enmeshing each child

an administrative net, but depends as well upon clothing the cit

f aeare-—an admitted wrongdoer--with practically unreviewablesdi

tion over the quality and extent of its own reformation."

The Defense Fund attorneys, who represented Negro Americansin

cases presented to the Supreme Court last year, cited the positions

of the Courts of Appeal on this issue: ae

They 'have shown great impatience with the all-too-deliberate slo

of the 12 year plans, Four circuits--the Third, Fourth, Fifth and

Beit noapeve now invalidated 'grade-a-year' plans, "the attorneys asse

Aléhéugh Negroes constitute 45 per cent of Atlanta's total school

eepulation, they have been alloted only 33 per cent of the school

Buildings and 40 per cent of the teachers and principals,

They suffer "serious overcrowding and higher pupil-teacher rati

the Defense Fund attorneys report.

Mrs. Motley was joined by Jack Greenberg, director-counsel “from the

Fund's New York City headquarters; E.E. Moore and Donald Holiowell,

of Atlanta. Attorneys A.T. Walden, Norman Amaker and J. LeVonni

Chambers, were of counsel, 5

— ees ez