Louisville Black Police Officers Organization Inc. v. City of Louisville Brief for Plaintiffs Proposed Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Order and Judgement

Public Court Documents

September 13, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Louisville Black Police Officers Organization Inc. v. City of Louisville Brief for Plaintiffs Proposed Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Order and Judgement, 1978. 58cacaec-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c65290f9-ee52-40fe-a0c5-af882f005a50/louisville-black-police-officers-organization-inc-v-city-of-louisville-brief-for-plaintiffs-proposed-findings-of-fact-conclusions-of-law-and-order-and-judgement. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

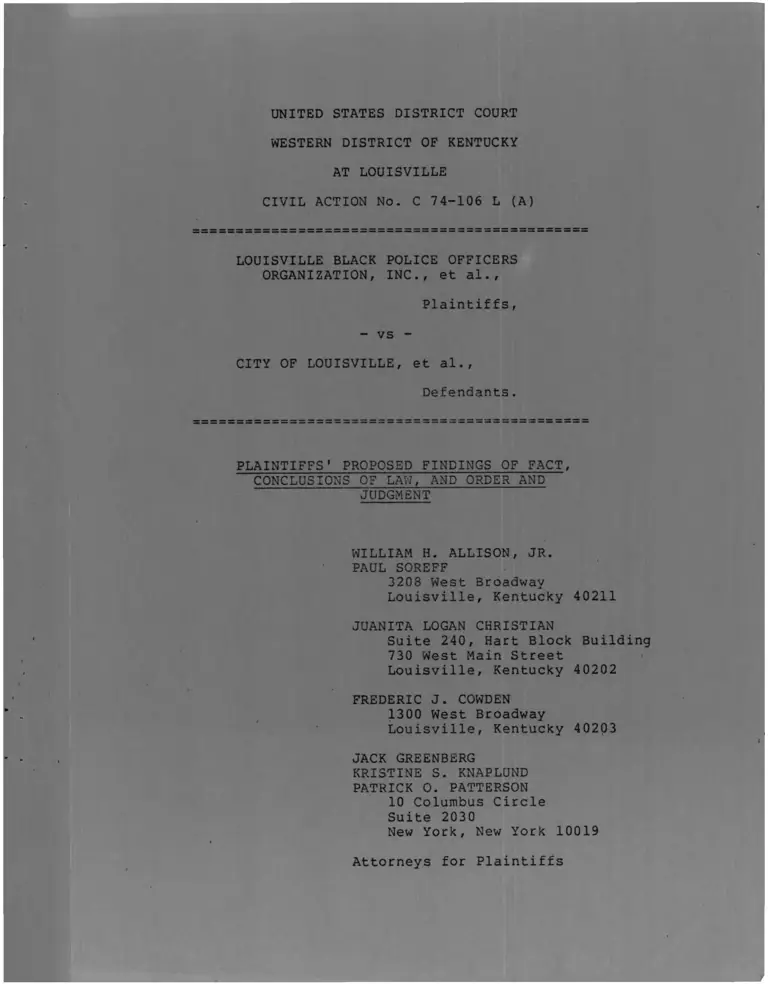

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

WESTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY

AT LOUISVILLE

CIVIL ACTION No. C 74-106 L (A)

LOUISVILLE BLACK POLICE OFFICERS

ORGANIZATION, INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs,

- vs -

CITY OF LOUISVILLE, et al.,

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT,

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW, AND ORDER AND

JUDGMENT

WILLIAM H. ALLISON, JR.

PAUL SOREFF

3208 West Broadway

Louisville, Kentucky 40211

JUANITA LOGAN CHRISTIAN

Suite 240, Hart Block Building

730 West Main Street

Louisville, Kentucky 40202

FREDERIC J. COWDEN

1300 West Broadway

Louisville, Kentucky 40203

JACK GREENBERG

KRISTINE S. KNAPLUND

PATRICK O. PATTERSON

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

WESTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY

AT LOUISVILLE

LOUISVILLE BLACK POLICE OFFICERS

ORGANIZATION, INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs. CIVIL ACTION NO.

CITY OF LOUISVILLE, et al., C 74-106 L (A)

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT,

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW, AND ORDER AND

JUDGMENT

Plaintiffs, by their counsel, submit the following pro

posed findings of fact, proposed conclusions of law, and proposed

order and judgment for consideration together with plaintiffs'

post-trial brief and supplemental post-trial brief.

Respectfully submitted,

--- -— __

WILLIAM H. ALLISON, JR.

PAUL SOREFF

3208 West Broadway

Louisville, Kentucky 40211

JUANITA LOGAN CHRISTIAN

Suite 240, Hart Block Building

730 West Main Street

Louisville1, Kentucky 40202

FREDERIC J. COWDEN

1300 West Broadway

Louisville, Kentucky 40203

JACK GREENBERG

KRISTINE S. KNAPLUND

PATRICK O. PATTERSON

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Dated: September 13, 1978 Attorneys for Plaintiffs

New York, New York

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

WESTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY

AT LOUISVILLE

LOUISVILLE BLACK POLICE OFFICERS

ORGANIZATION, INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

CITY OF LOUISVILLE, et al.,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION NO.

C 74-106 L (A)

PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT I. 2

I. The Action and the Parties

1. This is a class action brought under Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.,

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983 for declaratory, injunctive, and other

relief from racial discrimination in recruitment, testing, selec

tion, hiring, assignment, promotion, discipline, and other

employment practices concerning positions in the City of Louisville

Division of Police.

2. The named plaintiffs are the Louisville Black Police

Officers Organization, Inc., a nonprofit organization composed of

black police officers; Shelby Lanier, Jr., the president of the

organization, and Gary Hearn, both of whom are black citizens of

the United States and residents of Kentucky, and both of whom are

employed as police officers in the Louisville Division of Police;

and Ronald Jackson, James Steptoe, and Len Holt, black citizens

of the United States and residents of Kentucky who have applied

for jobs as police officers in the Louisville Division of Police.

Pursuant to Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. P., the named plaintiffs have

been certified as representatives of the classes defined in the

order entered by the Court on June 27, 1975, as amended on April

22, 1977.

3. The defendants are the City of Louisville, the Mayor

of Louisville, the Chief of the Louisville Division of Police,

the Louisville Civil Service Board and its members, and the

Personnel Director of Louisville. The Louisville Civil Service

Board and the Personnel Director are responsible for selection

and certification of persons for positions in the Louisville

Division of Police and other civil service positions. Priebe,

JL/Vol. I, 6/20/77 at 31. The Louisville Division of Police is

engaged in crime prevention and detection, apprehension of

alleged criminals, and the provision of social services and

counseling. Nevin, Vol. IV, 6/23/77 at 480. The primary opera

tions of the Division'are within the Louisville city limits. Id.

at 488.

1/ Citations in this form refer to the transcript of the trial

in this action.

- 2 -

II. Population Statistics

4. The following chart shows the percentage of black

persons in the total population for each geographic area in

each year indicated. The geographic boundaries of the areas

included in the "Metropolitan Area" column varied somewhat during

the period under review, as indicated in the census data cited

as sources.

Metropolitan Jefferson City of

_________________Area_________________ County____________Louisville

1940 12.4%* 13.3%* 14.8%*

1950 11.5%* 12.9%* 15.6%*

1960 11.5%* 12.8%* 17.9%*

1970 12 .2%** 13.8%*** 23.8%***

1975

estimate 14.2%****

Sources: * Appendix A

** PX 113

*** DX 2 7

**** PX 114; Weir, Vol. V, 9/30/77 at 869-70

- 3-

5 .

The following chart provides a more detailed breakdown

of the percentage of blacks in various population subgroups in

each of the geographic areas indicated for the year 1970.

Geographic

Area______

Black %

of Total

Popula

tion____

Black % of

Population

25 Years of

Age & Older

With 4 Years

of High Black % of

School and population

No Further 18-24 Years

Education of Age______

Black % of

Population

18-24 Years

of Age Not

Enrolled in

School Who

Have Com

pleted 4

Years of

High School

Black % of

Population

18-24 Years

of Age En

rolled in

their 4th

Year of

High School

SMSA* 12.2 8 . 9%** 11 . 88% 11.3% 14.1%

Jefferson***County 13.8% 10.3% 13.3%

City of****Louisville 23.8% 19.0% 21.4% 2 3 .5% 2 3 .4%

Source: * PX 113

■k k PX 116, Table 83 at 258, Table 91 at 298.

k k k PX 112

k k k k PX 111

- 4 -

III. History of Racial Discrimination

6. From 1940 to 1960, the total number of officers

in the Louisville Division of Police was approximately

400-500. Hughes, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 126; Taylor, Vol. I,

3/9/77 at 198; Thornberry, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 404;

Haendiges, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 284. In the 1940s, there

were 20-25 black officers. Taylor, Vol. I 3/9/77 at 198.

In 1951-1953, when James Thornberry was Director of Safety,

30-40 blacks were recruited, and a number of black officers

were hired and remained on the force. Thornberry, Vol. Ill,

6/22/77 at 406. Thereafter in the 1950s, there were 30-40

black officers on the force. Haendiges, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at

287; Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 8. The total number of officers,

and the percentage of black officers in each year from 1964

until the time of trial are set forth in the following table

(from PX 38) :

Date

Total Number

Of Officers

Number Of Black

Officers

Percentag

Black Off

1/1/64 524 32 6.1%

1/1/65 528 33 6.3%

1/1/66 532 34 6.4%

1/1/67 537 34 6.3%

1/1/68 557 37 6.6%

1/1/69 604 38 6.3%

1/1/70 621 39 6.3%

- 5-

Date

Total Number

Of Officers

Number Of Black

Officers ______

Percentage Of

Black Officers

1/1/71 624

1/1/72 664

1/1/73 692

1/1/74 765

1/1/75 789

3/1/77 714

38 6.1%

37 5.6%

39 5.6%

43 5.6%

55 7.0%

53 7.4%

7. From at least 1944, the defendants and their predecessors

maintained a pattern and practice of hiring and promoting blacks for

a limited number of "black only" jobs, and they maintained a strict

limit on the number and percentage of blacks on the police force at

any given time. PX 7, 38; Fraction, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 78-/9, 119;

Tay]or, Vcl. I, 3/8/77 at 195, and Vol. II, 3/10/77 at 216.

There have never been more than 55 black officers on the force

at any one time in the past 26 years. Fraction, Vol. I, 3/8/77

at 78; PX 38.

8. In 1944, 11 black officers were hired specifically

to form three black platoons, each headed by the city's first

three black Sergeants. Taylor, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 195. Seven

years later, in 1951, 6 black officers, including Robert Fraction,

were hired to replace officers who had left the three black pla

toons. These new officers were all assigned to the three black

platoons. Fraction, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 119. Although between

15 and 82 new white officers were accepted into police recruit

school classes which graduated in each year from 1964 through

1973, no more than 2 new black officers were ever accepted into

- 6-

recruit school classes which graduated in any of those years,

as set forth in the following table (from PX 7): 9

Number of Whites Number of Blacks

Accepted Into Accepted Into

Graduation Year Classes Classes

1964 25 2

1965 15 0

1966 38 2

1967 29 2

1968 16 0

1969 24 1

1970 24 0

1971 36 0

1972 28 2

1973 82 2

9. The defendants maintained a longstanding policy of

segregated assignments of black officers. Until approximately

1970, the areas patrolled by the Division of Police consisted

of four districts within the Louisville city limits. Between

1970 and 1974, the district boundaries were redefined and new

fifth and sixth districts were created. Lanier, Vol. IV,

4/28/77 at 710-711; Haendiges, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 293. Until

the early 1960s, all black uniformed patrol officers were assign

ed to work in the predominately black area of the second district

which was bounded by 6th Street on the east, 14th Street on the

west, Jefferson Street on the north, and Esquire Alley or Broad

way on the south. Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 7-8; Thornberry,

- 7-

Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 404-405; Nevin, Vol. IV, 6/23/77 at 490;

Haendiges, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 281, 290-292. Although as late

as 1964 most black officers were still assigned to the second

district, more blacks were assigned to the West End area of the

fourth district as the black population grew in that area.

Haendiges, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 281, 292-93. When blacks were

assigned to the fourth district, they were only allowed to

patrol in the black sections of the district. Lanier, Vol. IV,

4/28/77 at 709-710.

10. At least until the late 1960s, black recruits were

assigned to a "black" district irrespective of their desires.

All white graduates of recruit school were given the opportunity

to request both the district and the type of work they desired.

Brown, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 562; Lanier, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at

699-701. Black recruit school graduates were told not to bother

filling out the assignment request forms which were normally

supplied because they would be assigned to the black areas re

gardless of their request. Brown, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 562;

Lanier, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 699-701. When black graduates

filled out the assignment request froms, they were consistently

sent to the black areas regardless of their request. Fraction,

Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 80; Brown, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 562; Lanier,

Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 699-701.

- 8 -

11. By 1969, no black officers had ever been assigned to

the first or third district. Fraction, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 91.

At the time of trial, the great majority of black officers were

assigned to the second, fourth, and sixth districts, v/ith only

one to three black officers assigned to each of the three re

maining districts. Lanier, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 720-21.

12. Until approximately 1964, the regular assignments of

all black uniformed patrol officers in the Division were restricted

exclusively to walking beats in the second district regardless

of the area or assignment which they requested. Fraction, Vol.

I, 3/8/77 at 80; Brown, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 562-63; Lanier, Vol. IV,

4/28/77 at 699-701. White uniformed patrol officers were given

regular assignments throughout the second district and in all

other districts throughout the city. Lanier, Vol. V, 4/29/77

at 843. Until approximately 1964, black uniformed patrol officers

were not assigned or allowed to ride in patrol cars, while white

uniformed patrol officers were assigned and allowed to ride in

patrol cars. Throughout the 1950s, the same beats that blacks

were forced to patrol on foot were also patrolled by police cars

staffed only by whites. These assignments were made without

reference to length of service on the force. Hughes, Vol. I,

3/9/77 at 155-56, 166-168; Taylor, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 202; Lanier,

Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 701.

- 9-

13. Although until approximately 1964 the regular assign

ments of black uniformed officers were always walking beats in

the second district, if there was a specific job or detail to be

performed which white officers did not want, blacks would be

assigned to it regardless of the district. Blacks were taken

off their beats to work details in other districts such as strikes,

fires, and other assignments considered undesirable by white

officers. Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 14; Fraction, Vol. I, 3/8/77

at 85-86; Lanier, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 712. The practice of

giving blacks details rejected by white officers or otherwise

giving blacks undesirable assignments continued until the time

of trial. Lanier, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 713-15.

14. In the 1940s and 1950s, black officers were totally

excluded from the Division's special squads. Taylor, Vol. I,

3/9/77 at 204, 211. Blacks were restricted to walking beats in

the second district (Thornberry, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 404-405),

except for a few blacks who were on general assignment in the

detective bureau (Nevin, Vol. IV, 6/23/77 at 490; Taylor, Vol.

I, 3/9/77 at 204) to be sent into black neighborhoods to deal

with crimes committed there (Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 18).

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, black police officers

continued to be largely excluded from the Division's prestigious

special squads. No black officers were members of the pawn shop

squad, the burgulary squad, or the personnel department. Ponder,

Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 17-19; Fraction, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 97. These

- 10-

special squads were desirable because they frequently involved

straight day work and week-ends off. Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77

at 17. Although the personnel department no longer exists (Lan

ier, Vol. V, 4/29/77 at 773) and the burglary squad was recently

decentralized (Nunn, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 353), no black officers

were ever assigned to these squads while they operated. Taylor,

Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 211. No black officer was ever given a

regular assignment on the highly prestigious homicide squad

until the appointment of Officer Jesse Taylor in 1963. Taylor,

Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 205. Although blacks sometimes were temporarily

assigned to the homicide squad to investigate specific cases,

there were no other black police officers in the homicide squad

when Officer Taylor retired in 1974. Id_. at 209-210; Fraction,

Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 110-12. Only since the commencement of this

lawsuit have blacks been given regular assignments on the pawn

shop and robbery squads. Lanier, Vol. V, 4/29/77 at 771; Fraction,

Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 88. As of the time of trial, no black officers

were regularly assigned to the auto theft squad or the homicide

squad. Id. at 91.

15. Activities at the Division of Police, were racially

segregated as a matter of routine. Black officers were required

to attend the regular daily roll call with all officers in the

assembly room on the main floor of City Hall. Only white officers

were allowed to conduct this daily roll call. On occasion, white

patrolmen would be promoted to acting sergeants, rather than

allowing a black sergeant to conduct the roll call. Ponder, Vol. I,

- 11-

3/8/77 at 8, 13; Taylor, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 202-203. Immediately

after the daily roll call, black officers were required to attend

a separate, racially segregated meeting in a basement office of

City Hall. There they received their orders from the black

commanding officers. This practice continued at least through

the 1950s. Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 9; Fraction, Vol. I,

3/8/77 at 86.

16. Until 1965, no black officer had ever been appointed

to the position of major. Hughes, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 152. There

has never been more than one black major at any time since 1965.

Nunn, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 339. No black officer has ever held

the position of captain, the highest ranking civil service

position in the Division of Police. Id_. at 338. There have

never been more than two black lieutenants at any one time; as

of September 1977, there were no black lieutenants out of

approximately 48 positions. Hughes, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 154-55;

Nunn, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 339. In approximately 1944, three black

sergeants' positions were created. There have never been more

than three black sergeants since that time. Id_. at 339-40; Frac

tion, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 89—90; Taylor, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 202 . As of

September 1977, there was only one black sergeant out of approxi

mately 64 positions. Nunn, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 339. At least

until the 1960s, the only way a black officer could become a

sergeant or a lieutenant was for one of the three black sergeants

or a black lieutenant to die, retire, or be fired. Fraction, Vol.

I, 3/8/77 at 116.

- 12-

17. Defendants maintained a policy of providing different

training to black and white officers. Until at least 1955, the

Division used separate, racially segregated facilities for the

physical training of police recruit^ and black recruits were

given less self-defense training at these facilities than white

recruits. Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 5; Fraction, Vol. I, 3/8/77

at 84. Until at least 1975, there were no black instructors

regularly assigned to the recruit school; there were no such

instructors at the time of trial. Lanier, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at

698-99.

18. Defendants restricted the availability of special

training for black officers. No black officers attended the

Southern Police Institute until 1952. The next blacks allowed

to attend the Institute were Officers Lyons and Coatley, in 1959.

DX 88; Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 16-17; Hughes, Vol. I, 3/8/77

at 184-85; Coatley, Vol. II, 3/9-10/77 at 346-48; Brown, Vol.

IV, 4/28/77 at 572-73. Until at least 1971, black officers were

not allowed or assigned to attend these long-term special training

programs or schools such as the F.B.I. Academy and the Southern

Police Institute on the same basis as white officers. Blacks

were allowed to attend seminars lasting one day or less, but

not on the same basis as whites. Hughes,-Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 184-85.

19. A working environment of racial prejudice against black

officers was prevalent in the Division of Police in the 1950s,

Thornberry, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 404, and it continues in the

- 13-

1970s in such forms as racial slurs on bathroom walls (Lanier,

Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 731), frequent use of the term "nigger"

by both patrol officers and commanding officers in the Division

(Nunn, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 371-73 ; Nevin, Vol. II, 9/27/77

at 392-93), and membership of white officers in the Ku Klux Klan

(id. at 398-404).

IV. Reputation and Recruitment

20. The Division of Police and the Civil Service Board have

a longstanding negative reputation in the black community for

engaging in discriminatory employment practices against black

applicants and black police officers. It is widely known in the

black community that black officers were restricted to walking

beats until the 1960s (Lanier, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 693), that

black officers were allowed to patrol only certain sections of

certain districts (_id. at 557, 565-67), that black officers were

not allowed in many of the squads within the Division of Police

(Taylor, Vol- II, 3/9/77 at 241; Lanier, Vol.iv, 4/28/77 at 705-

706), that black officers were assigned to undesirable details

(id. at 712), and that black sergeants and lieutenants were only

permitted to command black officers (id_. at 703-704) . Because

black officers were not allowed to drive patrol cars and therefore

had to call for cars driven by white officers to transport suspects,

the reputation in the black community was that black officers were

not permitted to arrest whites. Lanier, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 693,702 ;

Brown, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 557.

- 14-

21. The reputation in the black community is that there is

discrimination in hiring against black applicants for jobs as

police officers (Hughes, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 159-60; Coatley,

Vol. II, 3/9/77 at 315; Brown, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 557; Lanier,

Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 693), and that the Division of Police has a

negative view of blacks which limits their promotional oppor

tunities (Hughes, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 159-60; Lanier, Vol. IV,

4/28/77 at 693). The black community's perception is that black

officers are treated as second class police officers withrn the

Division (Lanier, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 693; Taylor, Vol. I, 3/8/77

at 213-14), and that there is a general pattern of discrimination

against blacks in the Division's employment practices (Brown,

Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 608-609). This negative reputation in the

black community has deterred many blacks from applying for jobs

as police officers. Taylor, Vol. II, 3/10/77 at 271; Fraction,

Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 98-99, 113-15; Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 39.

22. With the exception of two short-range efforts to hire

blacks to be police officers, one in approximately 1944 to fill

all-black platoons (Taylor, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 195-97) and the other

in the early 1950s (Thornberry, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 404-405), the

defendants did not become actively involved in any efforts to re

cruit black applicants for jobs as police officers until after this

lawsuit was filed in 1974. PX 3, 5513-14; Nevin, Vol. IV, 6/23/77

at 517-19; Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 623; Taylor, Vol. II,

3/10/77 at 279. Prior to that time, the Louisville Urban League

and the plaintiff Louisville Black Police Officers Organization

- 15-

attempted to recruit black applicants (Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77

at 614-15, 623; Brown, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 614-15; Ponder, Vol. I,

3/8/77 at 25-26) but the defendants interfered with these efforts

(Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 30-34; Arnold, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 771).

In 1975, after Jack Richmond had left his position as head of Civil

Service, the Civil Service Board began its first active efforts to

recruit black applicants for jobs as police officers. Thornberry,

Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 409-11; Bryan, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 418-19.

V. Pre-1974 Selection Practices

23. The procedures used by the defendants to select police

officers prior to the commencement of this action in 1974 had a

susbstantial adverse impact on black applicants and potential

applicants. See proposed findings 6-8, supra. The Civil Service

Board and the Division of Police had a negative reputation in the

black community for discriminating against black applicants, black

recruits, and black officers, and many blacks did not apply because

of this reputation. See proposed findings 20-21, supra. Despite

this negative reputation, black persons applied for jobs as police

officers even before the defendants became involved in any active

minority recruitment program. For example, between July and

December of 1973, out of a total of 413 applicants for jobs as

police officers, 330 (80%) were white and 83 (20%) were black.

PX 71, Books 6-7. But of the 84 officers appointed in 1973, 82

(98%) were white and only 2 (2%) were black. PX 7. Many blacks

- 16-

applied or attempted to apply but were not hired as police officers

in the years preceding the filing of this lawsuit. Coleman, Vol.

IV, 9/29/77 at 614-24; Boyd, Vol. I, 4/25/77 at 37-47; Tutson, Vol.

IV, 4/28/77 at 544-51; Brown, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 580-85, 625.

24. From some time prior to 1965 through November 1974, appli

cants for jobs as Louisville police officers were required to com

plete the following selection procedures, generally in the following

order (Lee, Vol. II, 6/21/77 at 257-59; Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at

43-44, 70):

(a) Satisfy the "necessary qualifications" stated on the

job description as to height, weight, "speech defect," "marked de

formity," vision, education, age, military discharge and Selective

Service status, "moral character," and arrest and conviction records

(see PX 63-67);

(b) Obtain an application from the Civil Service office

receptionist, and complete and file the application;

(c) Take a pass-fail physical fitness test which con

sisted of push-ups and similar exercises (see PX 63-67) and which

was administered by representatives of Civil Service and the Division

of Police;

(d) Take the scored written examination administered by

Civil Service (PX 19-20 from prior to 1965 until 1971, PX 18 from

1971 until mid-1975; see proposed findings 26-27, infra);

(e) Take a pass/fail medical examination administered by

a physician under contract with Civil Service;

(f) Undergo a background investigation conducted by the

Division of Police;

(g) Take a pass/fail oral interview conducted by Civil

Service (Richmond Dep. Ex. 10); and

- 17-

(h) Receive a rating from Civil Service for "training

and experience."

25. In January 1975, the Civil Service Board reviewed its

selection procedures for police officers and other positions and

made the following findings: the receptionist was making all

decisions as to the right of an applicant to fill out an applica

tion, without even conducting an initial interview to determine

whether the applicant met the minimum qualifications; agency

requisitions were not being process in accordance with Civil

Service rules and regulations; applicants who were certified by

Civil Service for employment were sometimes disqualified by the

agencies without any written reasons; proper eligibility lists

were not maintained; a backlog of vacancies had developed, and

open-continuous testing had to be used for several months to

eliminate the backlog; proper job analysis procedures were not

followed; the written test (PX 18) was not validated and was

deficient in many respects (see proposed finding 27, infra);

the oral interviews for police officer were unstructured and

subjective, and they were not validated; test weights were set

in an arbitrary manner; the physical fitness standards were not

valid and they did not necessarily measure physical stamina or

physiological ability to tolerate stress; the Division of Police

conducted the background investigation and made recommendations

to disqualify applicants which usually were accepted by the Civil

Service Director without information as to whether the reason for

- 18-

disqualification was job-related; and the practice of giving a

"training and experience" rating gave an extra advantage to

persons with "inappropriate" training and experience which was

not required to do the job and also benefited applicants who

received high scores on the unvalidated written test. DX 75,

"Narrative " at 2-14; "Louisville Civil Service Board Selection

Procedures and Recruitment Program, Book I" -- "Written Entrance

Test " at 1-2; "Oral Interview " at 1, 3-4; "Background Investiga

tion " at 1; "Physical Agility Test " at 1.

26. From some time prior to 1965 until 1971, the defendants

used the Public Personnel Association's written "Test for Policeman

(10-D)," PX 19-20, as a device for selecting among applicants

for the job of police officer. PX 17; Richmond Dep., 5/23/77

at 149-51, 198-99; Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at 190-91. Defendant

Jack Richmond, Director of Civil Service from 1965 through late

1974, was aware in 1965 of serious problems of test security and

of allegations that some tests had been "compromised," Richmond

Dep., 5/11/77 at 19, but the defendants continued to use Test

10-D until 1971. Id., at 198-99; Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at

190-91. The defendant Civil Service Board determined that parts

of this test were not job-related or did not apply to the job of

a Louisville police officer, and the Board decided in 1971 to stop

using this test and to use another written test in its place.

Richmond Dep., 5/23/77 at 149; Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at 190-91.

27. From 1971 to 1975, the defendants used "Examination

for Police Patrolman No. 0044," PX 18, as the written test for

- 19-

entry-level police officer jobs. PX 17; Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77

at 190-91. This test had a substantial adverse impact on black

applicants; in 1975, only 12 of 342 white applicants (3.5%) failed

this test, but 14 of 93 black applicants (15.1%) failed it. DX 75,

"Statistical Data, Book Three" — "General Statistical Summary,

Sworn Personal," at 1(6; Priebe, Vol. I, 9/26/77 at 127-29. This

test was not job related. Thornberry, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 411, 413;

Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at 182-85, 188-200. The defendant Civil

Service Board found in 1975 that all of its written tests were

defective in certain respects and that most were defective in

certain additional respects. DX 75, "Narrative" at 8, 12, 14.

The Board further found that Police Patrolman Examination No.

0044 had been scored and assigned a weight of 65% in the total

examination process without any available rationale for the

cut-off score of 52, and that the test was not validated. DX 75,

"Louisville Civil Service Board Selection Procedures and Recruit

ment Program, Book I" — "Written Entrance Test" at 1-2. The

written test also had been administered in a manner which permitted

candidates to memorize the items; many of the items did not adequately

differentiate between candidates; and the test placed too much

emphasis on reading and mathemacics skills and was "approximately 80-

90% invalid." Olges, Vol. I, 7/11/77 at 155, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at 182-

85, 188-200; DX 38. As a result of these findings, the Board in

1975 decided to end its use of Police Patrolman Examination No.

0044 for selecting police officers, and it directed the development

of a new examination. Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at 199-200; Priebe

Dep., 2/17/77 at 74.

- 20 -

28. During the period that Jack Richmond was the Civil

Service Director, 1965 through late 1974, applicants were not

certified or appointed in rank order from eligibility lists;

instead, whenever the Division of Police notified Richmond

that it had vacancies to fill, applicants were put through the

selection procedures set forth in proposed finding 24, supra, and

those applicants who successfully completed the procedures were then

referred by Richmond to the Division for appointment. Richmond Dep.,

5/11/77 at 43-44, 84-85; Lee, Vol. II, 6/21/77 at 260-61; Arnold, Vol.

IV, 9/29/77 at 767, 780-82; Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 658; DX 75

narrative at 4. Richmond had broad discretionary authority over the

operation of the entire civil service selection and referral

process throughout this period (Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at

629-30, 658; Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 43-99), including the

sole authority until 1972, and substantial authority thereafter

until his departure in 1974, to determine who passed and who

failed the subjective and unstructured oral interview examination

for police officer. Id., 5/11/77 at 79, and 5/23/77 at 247-48;

Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at 182-85; Arnold, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at

768; Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 630; DX 75, "Narrative" at 8-9

and "Louisville Civil Service Board Selection Procedures and Re

cruitment Program Book I" -- "Oral Interview," at 1. While

Richmond was the Civil Service Director, black applicants were

subjected to differential treatment on the basis of their race, and

it was substantially more difficult for blacks than whites to

become police officers. Thornberry, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 409-410;

- 21 -

Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 634-35; Arnold, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at

771.

29. During this period, blacks who attempted to apply were

arbitrarily denied applications, black applicants were subjected

to unexplained delays in the processing of their applications,

and black applicants were disqualified on the basis of inaccurate

information which defendants refused to correct. See Boyd, Vol. I,

4/25/77 at 39, 43-44, 48; Lyons, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 657-60, 670;

Jackson, Vol. II, 4/26/77 at 255-62; Hearn, In Camera Tr., 3/10/77

at 4-23, 109. For many black applicants, only their perseverance

in investigating delays and correcting defendants' misinformation

led to their eventual appointment, with little or no assistance

from defendants. See Lyons, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 661-62; Jackson,

Vol. II, 4/26/77 at 262; Hearn, In Camera Tr., 3/10/77 at 13-21.

30. During this period, many black applicants encountered

subjective criteria in the oral interview and background inves

tigation which were not job-related. See Richmond Dep., 5/23/77

at 240-42; Hearn, In Camera Tr., 3/10/77 at 9; Holt, Vol. II, 3/10/77

at 406; Thomas, Vol. Ill, 4/27/77 at 479; Lyons, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at

662. Defendants also rejected applicants on the basis of criteria

which had a disparate impact on blacks and were not job-related,

such as juvenile and adult arrest records, see PX 63-67, 79, 85,

and Richmond Dep., 5/23/77 at 312; maximum weight standards, see PX

63-67 and VonderHaar, Vol. Ill, 9/28/77 at 431; and financial con

dition, see Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 76.

VI. 1974-1976 Selection Practices

31. From 1974 to 1977, the following numbers of blacks and

whites were appointed as police officers in each year:

- 22 -

Year Number of

Whites

Appointed

Number of

Blacks

Appointed

1974 78 21

1975 31 11

1976 11 0

1977 28 1

Source in Record

PX 54

PX 53; Priebe Dep. 2/11/11,

Ex. 3 5 5

Preibe, Vol. I, 9/26/77 at 116

PX 15; PX 52

As of December 1976, 15 of the 32 blacks appointed as police

officers in 1974 and 1975 (46.9%) were no longer employed by

the Division, but only 18 of the 109 whites appointed in 1974

yand 1975 (16.5%) were no longer employed. Id_; PX 39.

32. After this action was filed in March 1974 and Richmond

left the position of Civil Service Director in late 1974, the

defendants continued until August 1975 to use essentially the

same procedures for selecting police officers as those set forth

in proposed finding 24, supra, except that the oral interview

was graded and assigned a weight of 20% of the total score, the

training and experience rating was assigned a weight of 15%,

and the written test was assigned a weight of 65%. DX 75,

"Statistical Data, Book Three," at "Police officer — Procedure

2/ PX 39 lists the names of all officers employed as of

December 1976. A few of these names are not clearly legible

on the exhibit. The above calculation interprets this exhibit

as indicating that William Baker, Douglas W. Johnson, and Kevin

L. Richardson were still employed as police officers, while

Brain Hackley and Charles T. Smith were no longer employed as

of December 1976.

- 23 -

Used from January 1, 1975 to August 1, 1975." During this period,

the Civil Service Board began to take some steps to improve the

defective procedures identified in its January 1975 review

(see proposed findings 25, 27, supra). DX 75, "Narrative" at 2-16.

33. From August 1975 until November 1976, applicants for

jobs as Louisville police officers were required to complete the

following selection procedures in the following order (DX 75,

"Statistical Data, Book Three," at "Police Officer — Procedures

Used from August 1, 1975 to October 31, 1975"; Priebe Dep.,

2/17/77 at 15-24):

(a) Obtain an application from the Civil Service

office and complete and file the application (Priebe Dep. Ex 2);

(b) Undergo an "intake interview" conducted by a

Civil Service interviewer who determined whether the applicant

satisfied the "necessary qualifications" stated on the job des

cription (PX 68-69);

(c) Take a scored Civil Service oral interview

(DX 42) which was assigned a weight of 35% of the applicant's

overall score;

(d) Take a scored Civil Service written test (DX 39)

which was assigned a weight of 65% of the applicant's overall

score;

(e) Undergo a "character investigation" in which

an applicant was disqualified if he or she had been convicted

of any felony or of more than two misdemeanors, or if there

was any criminal action pending;

- 24 -

(f) Take a pass/fail medical examination (DX 90)

administered by a physician under contract with Civil Service;

(g) Take a "stress test" (DX 72) administered by a

physiologist under contract with Civil Service; the results of this

test were not used to pass or fail applicants prior to November 1976

(DX 75, "Louisville Civil Service Board Selection Procedures and

Recruitment Program, Book I" — "Physical Agility Test," at 2);

(h) Be assigned a place on a ranked eligibility list

on the basis of the written test score and the oral interview score;

(i) Be certified by Civil Service to the Division of

Police as eligible for appointment;

(j) Undergo a background investigation conducted by the

Division of Police (Casper Dep., 3/2/77, at 21-22, 42-44);

(k) Take an oral interview conducted by the Division

of Police (Casper Dep., 3/2/77, at 22-23).

34. From August 1975 until November 1976, applicants were

certified and appointed in rank order from eligibility lists com

piled as stated in finding 33, supra. When the Division of Police

requested a certain number of applicants, Civil Service certified

as eligible for appointment a number of applicants from the top of

the eligibility list equal to the number requested plus two. Priebe

Dep., 2/17/77 at 19-21, 22, 24. The Division of Police then con

ducted a background investigation and an oral interview (see finding 33,

supra) and selected the applicants to be appointed. Id.* at 21, 22, 24.

- 25 -

35. The written test which was used between August 1975 and

November 1976 (DX 39) did not have a substantial adverse impact on

black applicants as it was used during that period. Stipulation of

Counsel, Vol. II, 6/21/77 at 273-74; Stipulation of Counsel, Vol. I,

7/11/77 at 157; Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at 226; Stipulation of

Counsel, Vol. I, 9/26/77 at 130-32.

36. During this period, some black applicants were subjected to

unexplained delays in the processing of their applications and others

were rejected on the basis of vague and variable medical disqualifica

tions. See Jackson, Vol. II, 4/26/77 at 268-73; Gaines, Vol. II,

4/26/77 at 160-84; Richardson, Vol. II, 4/26/77 at 197-98,210-14;Priebe,

Vol. I, 9/26/77 at 91; VonderHaar, Vol. Ill, 9/28/77 at 454-56, 493.

Defendants also rejected applicants on the basis of criteria which

had a disparate impact on blacks and were not job-related, such as

maximum weight standards which discriminated against black females,

PX 81, Table 45; VonderHaar, Vol. Ill, 9/28/77 at 431.VII. 1976-1977 Selection Practices

37. From November 1976 until the time of trial, applicants

for jobs as Louisville police officers were required to complete

the following selection procedures in the following order (PX 23;

Priebe Dep., 2/17/77 at 15-21; Casper Dep., 3/2/77 at 21-23, 42-44):

(a) Obtain an application from the Civil Service office

and complete and file the application (Priebe Dep., Ex.2);

(b) Undergo an "intake interview" conducted by a Civil

Service interviewer who determined whether the applicant satisfied

the "necessary qualifications" stated on the job description

(Priebe Dep. Ex. 1);

- 26 -

(c) Take a scored Civil Service written test (PX 93)

which was assigned a weight of 75% of the applicant's total score

(Priebe, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 248-49);

(d) Take a scored Civil Service oral interview (DX 57)

which was assigned a weight of 25% of the applicant's total score

(Priebe, Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 248-49);

(e) Be assigned a place on a ranked eligibility list on

the basis of the oral interview score and the written test score;

(f) Take a pass/fail medical examination (DX 91-94)

administered by a physician under contract with Civil Service;

(g) Take a pass/fail "stress test" (DX 72) administered

by a physiologist under contract with Civil Service;

(h) Be certified by Civil Service to the Division of

Police as eligible for appointment;

(i) Undergo a background investigation conducted by the

Division of Police;

(j) Take an oral interview conducted by the Division of

Police.

38. In March 1977, 31 applicants were certified in rank order

from an eligibility list compiled as stated in finding 37, supra.

PX 52. Civil Service certified as eligible for appointment a number

of applicants from the top of the eligibility list equal to the

number requested by the Division of Police plus two. Priebe Dep.

2/17/77 at 19-21; PX 52. Following this process, 1 black applicant

and 28 white applicants were appointed in March 1977. PX 15; PX 52.

-2 7-

39. In April 1977, 25 applicants were certified by Civil

Service in rank order from the eligibility list compiled as stated

in finding 37, supra. for appointment as police officers in a

recruit class which was scheduled to begin in May 1977. PX 52;

Priebe, Vol. I, 9/25/77 at 104-106. All of these applicants were

white. Id_. Following the filing in April 1977 of plaintiffs'

motion for a preliminary injunction concerning that recruit class,

the defendants agreed to postpone the class indefinitely. The Court

subsequently reserved decision on the plaintiffs' motion for a

preliminary injunction until completion of this portion of the trial

on the merits. Order, 6/17/77. The defendants have not certified

or appointed any police officer applicants since April 1977.

40. In May 1977, the defendant Civil Service Board changed

its practices regarding certification so that in the future the

number of candidates certified from an eligibility list for appoint

ment as police officers would be determined as follows: for one

opening,three names would be certified; for two through ten openings,

the names of two times the number of openings would be certified;

and for more than ten openings, the names of three times the number

of openings, would be certified. Priebe, Vol. I, 6/20/77 at 121-27;

Priebe, Vol. I, 9/26/77 at 5-6. The result of this change would be

the certification of names of applicants appearing substantially

lower on the ranked eligibility lists than occurred with prior

certification practices. Id.

41. As used by the defendants, the written test which was used

for selecting police officers between November 1976 and the time of

- 28 -

trial (PX 93) had a substantial adverse impact on black applicants.

Approximately 23.5% (222/944) of all applicants during this period

were black. PX 35. The written test, which was developed by the

Educational Testing Service, Inc., and is entitled "Multijurisdic

tional Police Officer Examination, Test No. 165.1" (hereinafter

"Test 165.1"), was administered to 480 white applicants and 135

black applicants on January 28, 1977. PX 33. The defendants set

the passing point at 128 correct answers out of the 150 items on

Test 165.1 (Gavin-Wagner, Vol. Ill, 7/13/77 at 361-62), and the

defendants assigned the score on Test 165.1 a weight of 75% in

determining rank on the eligibility list (id_. at 366-67; Priebe,

Vol. II, 9/27/77 at 248-49). Whites passed at more than twice the

rate of blacks: 78% of the whites passed (374/480), but only 36.3%

of the blacks passed (49/135). PX 33. Only 5 of the 135 black

applicants, or 3.7%,scored high enough to be among the top 100 on

the eligibility list, while 95 of the 480 white applicants, or 19.8%,

ranked among the top 100. PX 35. No more than 100 new police

officers have ever been appointed in any one year (see proposed

findings 8, 31, supra), and the eligibility list then in effect

was scheduled to expire in one year (PX 52). Only 50 to 60 vacancies

were projected for that year. Gavin-Wagner, Vol. Ill, 7/13/77 at

362. The results of defendants' use of Test 165.1 are summarized

in the following table showing the initial number and percentage

of black applicants and the number and percentage of black appli

cants remaining after each stage of the selection process leading

to compilation of the eligibility list (from PX 35):

-2 9-

Stage of Selection

Process

Number

of Black

Applicants

Total

Number of

Applicants

Percentage

of Black

Applicants

Application 222 944 2 3.5%

After

Disqualification 207 883 2 3.4%

After

Written Test 49 427 11.5%

After

Oral Interview 48 401 12.0%

On Eligibility List 48 401 12.0%

In Top 100 of

Eligibility List 5 100 5.0%

42. Test 165.1 purports to measure "intellectual abilities"

which are traits or constructs. These traits or constructs —

verbal comprehension, paired associate memory, memory for rela

tionships, memory for ideas, semantic ordering, induction, problem

sensitivity, spatial orientation, spatial scanning, visualization

are not operationally defined in terms of observable aspects of

work behavior of the job of a police officer. See plaintiffs'

post-trial brief at 56-62.

43. Test 165.1 does not consist of a representative sample

or close approximation of the work behaviors of police officers.

It contains items which place a premium on reading and verbal

skills and which do not adequately represent the highly physical

and personal job of a police officer. See plaintiffs' post-trial

brief at 62-66.

44. Test 165.1 involves knowledge, skills, and abilities

which police officers learn in recruit school and on the job.

See plaintiffs' post-trial brief at 66-69, 76-79.

- 30 -

45. Test 165.1 does not represent a critical work behavior

or work behaviors which constitute most of the important parts of

the job. See plaintiffs' post-trial brief at 69-74.

46. The sample subjects used in the concurrent criterion-

related validity study which is reported in DX 31 (hereinafter

the "ETS study") were not representative of the candidates normally

available in the relevent labor market for the job of police

officer in Louisville. See plaintiffs' post-trial brief at 76-82.

47. The supervisory ratings used as criterion measures in

the ETS study were contaminated by rater bias. See plaintiffs'

post-trial brief at 83-84.

48. A study of test fairness was technically feasible but

was not performed as part of the ETS study. See plaintiffs'

post-trial brief at 85-88.

49. The results of the ETS study showed that total test

score had significant positive correlations with 2 of 15 rating

dimensions in site 1, no significant correlations with any

rating dimensions in site 2, significant positive correlations

with 11 rating dimensions in site 3, and a significant negative

correlation with one rating dimension in site 4. Across the four

sites as a whole, there were no significant correlations between

total test score and 46 of the 60 rating dimensions. See plain

tiffs' post-trial brief at 88-91.

50. The ETS study does not demonstrate that Test 165.1 is valid for

use in the selection of Louisville police officers. Police officers in

Louisville have not been shown to perform the same work behaviors as the sample

- 31 -

subjects in the ETS study. An internal predictive study of the

validity of Test 165.1 in selecting Louisville police officers is

feasible. See plaintiffs' post-trial brief at 91-95.

51. The cut-off score set by defendants on Test 165.1, their

use of the test as a ranking device, and their use of the test as

an initial screening device were arbitrary and did not result in

the selection of persons better qualified to be police officers.

These uses of Test 165.1 were contrary to the findings of the

validity study reported in DX 32 (hereinafter the "Delaware study").

See plaintiffs' post-trial brief at 95-100.

52. The test administered by defendants to police applicants

in August 1975 (DX 39) had less adverse impact on blacks as used

at that time than Test 165.1 as used by defendants in 1977, and

it equally served defendants' interest in the selection of

capable police officers. Using Test 165.1 in accordance with the

findings of the Delaware study would also reduce the adverse impact

on blacks while serving defendants' interest in,the selection of

capable police officers. See plaintiffs' post-trial brief at 100-103.

VIII. Achieving a Representative Police Force

53. The residents of the City of Louisville have a substan

tial interest in being served by a police force which is repre

sentative of the community as a whole. The fairness and effec

tiveness of the police force would be enhanced and police-com

munity relations would be improved by the appointment of a

representative number of black officers. See plaintiffs' post

trial brief at 109-114.

- 32-

54. From 1964 to 1975, the number of officers in the Division

of Police increased by an average of approximately 24 officers each

year. See PX 38. In the same period, an average of approximately

39 new officers were hired each year. See PX 7, PX 54. Assuming

that both the increase in the size of the force and the hiring of

new officers continue at the same rate, and that no current or

future black officers leave the force, it would take more than 34

years for the percentage of black officers on the force to increase

from the current 7.4% to 25% if one out of every four new officers

hired is black, and it would take more than 9 years for the per

centage of black officers on the force to increase to 25% if one

out of every two new officers hired is black. See plaintiffs'

post-trial brief at 114-16.

IX. Administrative Procedures

55. On March 28, 1973, plaintiff Shelby Lanier, Jr. lodged

a charge of employment discrimination (PX 48) with the U.S. Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) against the City of

Louisville - Division of Police. The charge alleged racial dis

crimination against Lanier personally and blacks as a class, and

it was filed by Lanier in his capacity as president of the plaintiff

Louisville Black Police Officers Organization, Inc. Lanier, Vol.

V, 4/29/77 at 846-48. The EEOC assumed jurisdiction over the charge

on June 8, 1973, and it served the charge on the Division of Police

on June 25, 1973, and on the Civil Service Board on July 9, 1973 .

- 33 -

PX 49 at 1. The EEOC conducted an investigation of the charge

and, on November 14, 1974, issued a decision containing the

following findings (PX 49):

There is reasonable cause to believe that Respondent

has violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 by failing to hire blacks because of their race.

There is reasonable cause to believe that both Re

spondents violated Title VII by failing to promote

Blacks because of their race.

There is reasonable cause to believe that Respondent

No. 1 has violated Title VII by retaliating against

Charging Party Lanier for opposing alleged unlawful

employment practices of Respondent. There is no

reasonable cause to believe that Respondent retalia

ted against Charging Party Brown because of his

opposition to certain of Respondent's employment

practices.

There is reasonable cause to believe that Respondent

discriminates against blacks in terms and conditions

of employment by subjecting them to more severe dis

ciplinary actions than similarly situated whites,

because of their race.

There is reasonable cause to believe that the Re

spondent is maintaining racially segregated job

classification in violation of Title VII.

There is no reasonable cause to believe that Re

spondent discriminated against Blacks in violation

of Title VII with respect to training opportunities,

and with respect to the allegation regarding perform

ance evaluation, there is insufficient evidence to

enable the Commission to make a determination. We,

therefore, withhold decision on this issue at this time.

56. On or about October 2, 1975, plaintiff Lanier received

from the U.S. Department of Justice a "Notice of Right To Sue"

entitling him to institute a civil action under Title VII within

90 days of the date of receipt of the notice. See plaintiffs'

motion for leave to amend complaint and to drop and add parties

plaintiff, 3/1/77, Ex. 3. Within 90 days of that date, plaintiffs

- 34 -

moved to amend their complaint to allege jurisdiction under Title

VII. The Court sustained this motion, Order, 1/28/76, and the

Court determined that plaintiff Lanier is a proper class represents

tive, Order, 4/22/77.

57. On April 4, 1973, plaintiff Gary Hearn lodged a charge

of discrimination in hiring (PX 1) with the EEOC against the City

of Louisville - Louisville Division of Police and the City of

Louisville Civil Service Board. On or about February 16, 1977,

plaintiff Hearn received from the U.S. Department of Justice a

"Notice of Right To Sue," entitling him to institute a civil action

under Title VII within 90 days of the date of receipt of the notice

See plaintiffs' motion for leave to amend complaint and to drop and

add parties plaintiff, 3/1/77, Ex. 5. Within 90 days of that date,

plaintiffs moved to amend their complaint to add Gary Hearn as a

named plaintiff and class representative and to assert his claims

under Title VII. The Court sustained this motion and determined

that plaintiff Hearn is a proper class representative. Order,

4/22/77.

- 35-

APPENDIX A

1940-1960 Population Statistics

Metropolitan Jefferson City of

Area_________ County____ _ Louisville

Blacks Total Blacks Total Blacks Total

1940 54,060 434,408 51,166 385,392 47,158 319,077

1950 66,265 576,900 62,620 484,615 57,657 369,129

1960 83,181 725,139 78,350 610,947 70,075 390,639

Source: 1960: U.S. Bureau of the Census

U.S. Census of the population: 1960

Volume I : Characteristics of the Population

Part 19: Kentucky at Table 21, Page 44 and

Table 28, Page 107.

1950: U.S. Census of the Population: 1950

Volume II: Characteristics of the Population

Part 19: Kentucky at Table 24, Page 47 and

Table 42, Page 90.

1940 : 16th Census of the United States

Volume II: Characteristics of the Population

Part 3: Kansas - Michigan

Kentucky at Table 36, Page 313; Table

45, Page 321 and Table 21, Page 207.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

WESTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY

AT LOUISVILLE

LOUISVILLE BLACK POLICE OFFICERS

ORGANIZATION, INC., et al,,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

CITY OF LOUISVILLE, et al.,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION NO.

C 74-106 L (A)

PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED CONCLUSIONS OF LAW 1 2

1. The defendants are "employers" and the interven

ing defendant Fraternal Order of Police, Louisville Lodge No. 6,

is a "labor organization" within the meaning of sections 701(b)

and 701(d) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(b), (d). The Court has jurisdiction

over the parties and jurisdiction over the subject matter of

this action pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(3) and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1343(3), (4).

2. The Court has determined that this action is

maintainable as a class action under Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. P.,

in accordance with the order of June 27, 1975, as amended

April 22, 1977:

IT IS ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the

plaintiff Louisville Black Police Officers

Organization, Incorporated, and the plain-

tiff Shelby Lanier, Jr., be and they are hereby

designated as representatives of a class which

is composed of all persons who are black and who

are now or have been police officers employed by

the City of Louisville and who allege that the

rules, regulations and practices of the defen

dants have discriminated against black police

officers on the basis of their race with regards

to assignment, promotion and discipline of

personnel.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the

plaintiffs Ronald Jackson, James Steptoe, Len

Holt, and Gary Hearn be and they are hereby

designated as representatives of a class which is

composed of black persons who have sought to

obtain employment with the Louisville Police

Department and who allegedly have been denied

such employment on the basis of arbitrary, ca

pricious and racially discriminatory practices

on the part of the defendants. Said class also

consists of all black applicants for positions

with the Louisville Police Department who will

in the future seek jobs with the Police Department,

and who may be denied employment because of the

allegedly racially discriminatory and arbitrary

practices complained of in the complaint. 3

3. The statistical evidence, the defendants' use of

arbitrary and subjective selection procedures and criteria which

are not job related, their long history of racial segregation

and overt employment discrimination, their negative reputation

for such discrimination in the black community,, their failure to

engage in any active effort to recruit black applicants until

after the filing of this lawsuit, and the testimony of individual

victims of discrimination establish that defendants (a) have en

gaged in intentional discrimination against blacks in recruit

ment, testing, selection, and hiring for positions as police

officers, and (b) have used selection procedures and criteria—

including written tests, juvenile and adult arrest records, fin

ancial condition, and maximum weight standards-— which have a

2

disparate impact on blacks and have not been shown to be signi

ficantly related to job performance. Therefore, defendants

have violated Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, and 42 U.S.C, § 1983

and the Fourteenth Amendment.

4. The improvement in the defendants' minority

recruitment practices and the temporary increase in the defen

dants' hiring of black police officers following the commence

ment of this action do not constitute a defense to plaintiffs'

claims of discrimination, nor do they provide any basis for

withholding affirmative hiring relief.

5. The defendants used the Multijurisdictional Police

Officer Examination, Test 165,1, in a manner which had an extreme

adverse impact on black applicants, and defendants did not demon

strate that Test 165.1 was manifestly related to performance of

the job of a Louisville police officer. Defendants did not es

tablish that Test 165.1 had been validated in accordance with the

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures (1978), 43 Fed.

Reg. 38290 (Aug. 25, 1978), or in accordance with other appropriate

legal and professional standards; defendants did not establish that

such evidence of validity as existed was applicable to the selection

of police officers in Louisville; and defendants substantially

increased the adverse impact of Test 165.1 by setting an arbitrarily

high passing point and by improperly using the test to rank applicants.

Therefore, the defendants' use of Test 165,1 violated Title VII and

42 U.S.C. § 1981.

3

6. In granting relief from unconstitutional and un

lawful discrimination, it is the Court's duty not only to prohibit

the continuation of discriminatory practices and to require the

development of nondiscriminatory procedures, but also to grant

effective affirmative relief from the effects of past dis

crimination. Numerical, race-conscious, affirmative hiring

relief is authorized, and in this case is required, by Title VII,

42 U.S.C. § 1981, and 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and the Fourteenth

Amendment.

7. The Court has a duty to require that qualified

blacks be appointed as police officers on an accelerated basis,

and the Court has discretion to require that such appointments

continue until the proportion of black officers on the Louisville

police force approximates the proportion of blacks in the

population of the City of Louisville. In view of the defendants'

extensive past discrimination and exclusion of blacks from the

police force, and in view of the resulting serious impairment of

the ability of the police force to provide fair and effective

law enforcement and other police services to the residents of

the City of Louisville, the Court will exercise its discretion

to require such relief in this case.

8. Plaintiffs' attorneys are entitled to an interim

award of reasonable attorneys' fees pursuant to § 706(k) of

Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(kl, and pursuant to the Civil

Rights Attorneys' Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

4

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

WESTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY

AT LOUISVILLE

LOUISVILLE BLACK POLICE OFFICERS

ORGANIZATION, INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v s .

CITY OF LOUISVILLE, et al.,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION NO.

C 74-106 L (A)

PLAINTIFFSr PROPOSED ORDER AND JUDGMENT

In accordance with and based upon the foregoing

findings of fact and conclusions of law, it is hereby ORDERED,

ADJUDGED, and DECREED that:

I. Declaratory Judgment

1. The defendants have engaged in discrimination

in recruitment, testing, selection, and hiring against the

named plaintiffs and members of their class because of their

race or color in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Ac

of 1964, as amended by'the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. ; 42 U.S.C. § 1981; 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983; and the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

II. General Injunctive Relief

2. The defendants and their officers, agents,

employees, successors in office, and all those acting in

concert or cooperation with them or at their direction or

under their control (hereinafter collectively referred to as

"the defendants") are permanently enjoined from engaging in

any act, practice, or policy with respect to recruitment,

testing, selection, or hiring which has the purpose or effect

of unlawfully discriminating on the basis of race or color

against any future employee or any applicant or potential

applicant for employment as a police officer in the Louisville

Division of Police.

3. The defendants are permanently enjoined from

(a) making any appointments to the position of police officer

based in whole or in part upon the scores of applicants on the

Multijurisdictional Police Officer Examination, Test 165.1, as

used by the defendants in 1977, or upon any eligible list based

in whole or in part upon the scores of applicants on that

examination; and (b) administering, promulgating eligible lists

based upon, making appointments based upon, or in any way acting

upon the results of any unlawful discriminatory examination or

other selection procedure for the position of police officer.

Ill. New Selection Procedures

4. The defendants are mandatorily enjoined to

develop lawful, nondiscriminatory selection procedures for the

position of police officer. In so doing, the defendants shall

2

comply with the following requirements:

(a) The new selection procedures shall be

developed within the shortest practicable period.

(b) The new selection procedures shall

be developed and, before they are used to select

police officers, validated in accordance with the

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures

(1978), 43 Fed. Reg. 38290 (Aug. 25, 1978).

(c) The new selection procedures shall

be submitted to counsel for plaintiffs and to the

Court before they are used to select police officers. Plain

tiffs Attorneys shall have a reasonable opportunity to

review defendants' submissions and to present their

objections, if any, to the Court, and the Court may

thereafter approve, disapprove, or modify the new selec

tion procedures proposed by defendants. The new pro

cedures shall not be used to select, certify, or appoint

police officers until such procedures have been approved

by the Court.

(d) After the Court has approved the new

selection procedures, and until such time as the per

centage of black officers in the Louisville Division

of Police approximates the percentage of black persons

in the population of the City of Louisville, the de

fendants shall select, certify, and appoint persons as

police officers in accordance with the following

provisions:

3

(i) For every two vacancies which occur

in such positions, one qualified black person shall

be appointed as a police officer.

(ii) If there is only one vacancy at any

given time, a qualified black person shall be

appointed to fill the vacancy. The next vacant

position may be filled by any qualified person.

(iii) If the number of black persons

eligible for certification or appointment at any

time is not sufficient to satisfy this requirement,

the defendants shall make no appointments to the

position of police officer until such time as this

requirement will be satisfied.

(iv) Any black person who is appointed as

a police officer, and who does not successfully

complete either the police recruit school or the

probationary period, shall not be counted toward

satisfaction of this requirement.

(e) Nothing contained herein shall re

quire or be construed to require the defendants to hire

any unqualified employee.

IV. Interim Selection Procedures

5. During the period required for the development of

lawful, nondiscriminatory selection procedures, the Court will

entertain requests by the defendants for permission to select,

certify, and appoint police officers under interim selection

procedures subject to the following provisions:

(a) Any such request shall "be submitted to coun-

4

sel for plaintiffs and to the Court, and it shall

state the circumstances which render such appoint

ments necessary or desirable.

(b) The request shall state the number

of appointments to be made and the desired effective

date(s) of such appointments.

(c) The request shall set forth the nature

of the interim procedures which the defendants propose

to use, the reasons for proposing those particular

procedures, and the grounds for believing that uhe

procedures will be based upon merit and fitness and

will be nondiscriminatory in purpose and effect. Plaintiffs'

attorneys shall have a reasonable opportunity to

review defendants' submissions and to present their

objections, if any, to the Court, and the Court may

thereafter approve, disapprove, or modify the proposed

interim procedures. The defendants shall not use any

interim procedure to select, certify, or appoint

police officers until such procedure has been approved

by the Court.

(d) After the Court has approved interim

selection procedures, and until such time as the per

centage. of black officers in the Louisville Division

of Police approximates the percentage of black persons

in the population of the City of Louisville, the de

fendants shall select, certify, and appoint persons

as police officers in accordance with the following

provisions:

(i) For every two vacancies which.

5

occur in such positions, one qualified black

person shall be appointed as a police officer.

(ii) If there is only one vacancy at

any given time, a qualified black person shall

be appointed to fill the vacancy. The next

vacant position may be filled by any qualified

person.

(iii) If the number of black persons

eligible for certification or appointment at

any time is not sufficient to satisfy this

requirement, the defendants shall make no

appointments to the position of police officer

until such time as this requirement will be

satisfied.

(iv) Any black person who is appointed

as a police officer, and who does not successfully

complete either the police recruit school or the

probationary period, shall not be counted toward

satisfaction of this requirement.

(e) Nothing contained herein shall re

quire or be construed to require the defendants to hire any

unqualified employee.

V. Recruitment

6. , The defendants are enjoined to continue or upgrade

minority recruitment programs which they utilized from November

1976 through January 1977. The defendants may increase or

otherwise improve such programs but may not reduce such programs

6

in any way without the prior approval of the Court. The defen

dants shall consult with the plaintiff Louisville Black Police

Officers Organization in developing, implementing, and main

taining effective programs for recruiting qualified black appli

cants for positions as police officers.

VI. Individual Relief

7. Each named plaintiff and each class member may file

a claim for individual hiring relief, back pay, retroactive seniori

ty, and other individual relief for discrimination based on race or

color in recruitment, testing, selection, or hiring for any entry-

level position as a police officer. All potential claimants shall

be given adequate notice of their right to file such claims. The

form and manner of such notice and the method of resolving such indi

vidual claims shall be determined by further order of the Court.

VII. Record-Keeping and Reporting

8. Until further order of the Court, the defendants shall

retain the records listed below. These records shall be made avail

able to counsel for plaintiffs for inspection and/or copying upon

written request.

(a) A list of all minority organizations and

schools contacted for recruiting purposes, showing the

date of each contact, persons contacted, name and position

of defendants' employee who made the contact, and nature

of the contact.

(b) A summary of all minority recruitment

efforts together with the date of such efforts and the

names and positions of defendants1 employee or agent who

made the contact and nature of the contact.

(c) All applications for positions as police

officers, and separate records which identify each

applicant by race.

7

(d) All test scores, whether written, oral,

or other, on tests used for selecting among applicants

for police officer positions, with identification of

the race of each tested applicant.

(e) The name, address, and race of each

person disqualified for any reason from being selected

as a police officer or police applicant, and the rea

son (s) for such disqualification.

(f) All form letters, with a list of addressees,

and copies of any individual correspondence used by

the defendants in connection with application, selec

tion, certification, or appointment of police officers.

(g) All eligible lists utilized for certi

fication or appointment of police officers, with an

identification of the race of each person on each

such list.

9. The defendants shall submit to counsel for plain

tiffs the following reports:

(a) Annually: A photostatic copy of the

EEO-4 form filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission for the Division of Police, within 10 days

of the filing of such form.

(b) Within 60 days of the entry of this order,

and every six months following the entry of this order

until further order of the Court, a report showing:

(i) Total number of sworn personnel

employed in the Division of Police by race,

_ within each rank (up to and including the

highest rank below the rank of chief) for the

8

first report; and thereafter the total number

of new sworn personnel employed by the Division

of police by race within each rank during the

intervening period since the last report, and

the total number of sworn personnel within each

rank by race who have retired, resigned, or other

wise been terminated during the intervening

period since the last report.

(ii) Statistical breakdown of the

applications made during the intervening period

since the last report by race, together with a

statistical breakdown of the acceptance or re

jection of such applicants by race by each stage

of the selection process.

(iii) The name, address, and telephone

number of any black police recruit or officer in

voluntarily terminated prior to completion of either

the recruit school or the probationary period, and

the reason for such termination.

(iv) The date on which each recruit class

commenced during the intervening period since the

last report and the numbers and percentages of

black persons and white persons in each such class.

(v) A cumulative report showing the

numbers of black persons and white persons appointed