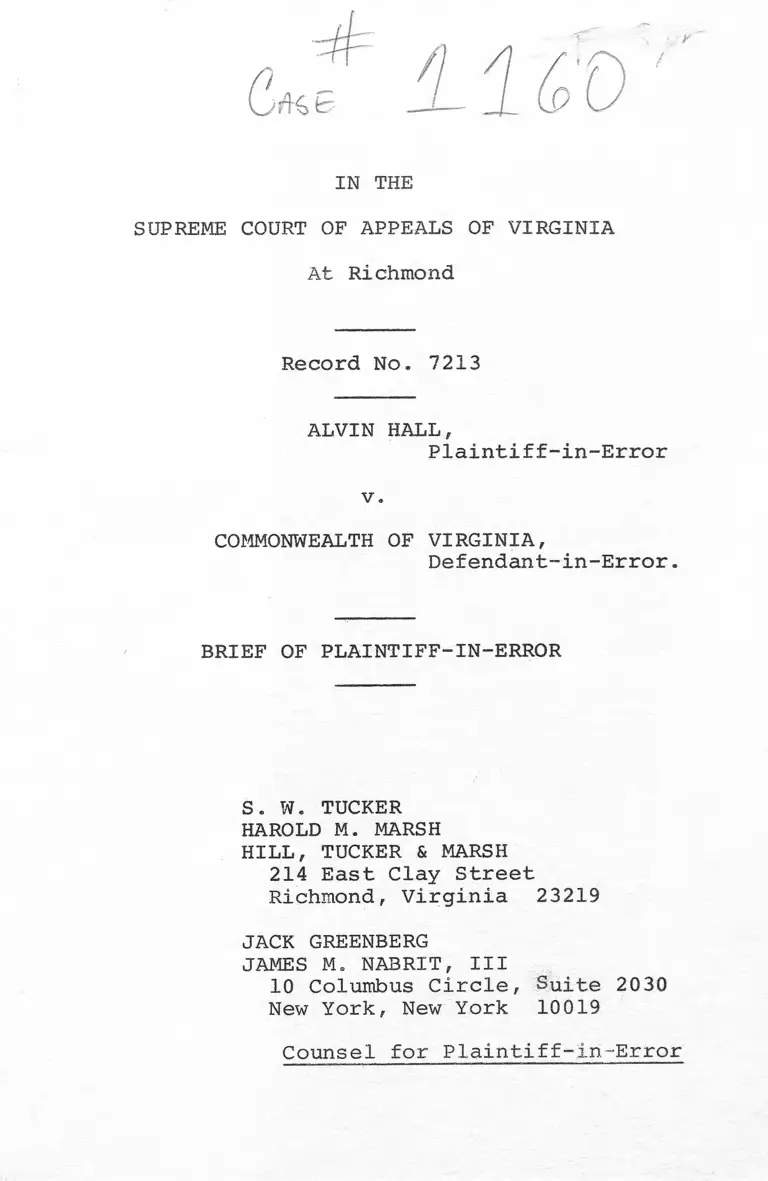

Hall v. Commonwealth of Virgina Brief of Plaintiff-in-Error

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hall v. Commonwealth of Virgina Brief of Plaintiff-in-Error, 1969. fc4e9221-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c69080d6-25a5-4b0b-bed5-36dd6b22945c/hall-v-commonwealth-of-virgina-brief-of-plaintiff-in-error. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

At Richmond

Record No. 7213

ALVIN HALL,

Plaintiff-in-Error

v.

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Defendant-in-Error.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFF-IN-ERROR

S. W. TUCKER

HAROLD M. MARSH

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiff-in-Error

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Statement Of Material Proceedings

Page

1

Statement Of The Facts * . . . . . . . . 4

The Assignment of Errors , . . . . . . .

The Question Presented

Argument . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I. The Plaintiff-In-Error Was Not

A Part Of The Assembly . . . . . . .

II. Uncontradicted And Unimpeached

Testimony Not Inherently

Incredible May Not Be

Arbitrarily Disregarded . . . . . .

III. Citizens May Not Be Impelled To

Forego First Amendment Rights For

Fear Of Violating An Unclear Law. .

A. Only One Definition Of

Unlawful Assembly Is

Challenged Here . . . . . . . .

B. The Constitutional Privilege

Transcends State Interest .. . .

C. The Statute Provides No

Standard For Ascertainment of

Forbidden Purpose . . . . . . .

D. The Statute Is Vague . . . . .

IV. No Overt Act Justified Arrest .■. .

Conclusion . « . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

7

8

8

12

14

14

17

20

21 -

23

26

28Certificate

Appendix (Richmond Ord. #68-79-44} • A P P - 1

11

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Page

Ashton Vo K e n t u c k y 384 U.S. 195,

86 SoCt 1407, 16 L. ed 2d 469 . , , 22,23

Baker v. Binder, 274 F, Supp, 658 . . 23

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296,

60 S.Ct, 90'G, 84 L, ed 2d 1213 . . 22

Carmichael v. Allen, 267 F. Supp,. 9 85, 2 3

Cox v, Louisiana, 379. U .S . 536,

85 S, Ct.. 453, .13 L, ed 2d' 471 . . 22

Devine v. Woodf; 286 F, Supp, 102 G . , 16

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U,S. 229,

83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L .ed 2d 697 . . . . 22

w'

Epperson & Carter v, DeJarnette, 164 Va.

482., 180 SE 412 . . . . . . . . . . ~ 12

Gamble v. Commonwealth, 161 Va. 1024,

170 SE 761 . . . . . . . . . . , .. 10

Giacco v* Pennsylvania, 382 UVS, 399,

86 S.Ct. 518, 15 L. ed 2d 477 . . . 21

Hague v. 0,1,0,, 307 U.S-. 496, 59 S.Ct.

954 ,.. 83 L, ed 1423 18

Heard vi Rizzo,. 281-F. Supp. 720 . . ■. 1 5

Lanzetta v. - New Jersey,. 306 U,S. 451,

S.Ct. 618, 83 L, ed 888 . = . . . . 2.1

ill

Page

Metropolitan L. Ins, Co, v„ Botto,

153 Va. 468, 14 SE. 625 . , . O «! ® 12

Powers v. Commonwealtk, 182 Va.

30 S„E, 2d 22 o . . , , , . ,

669,

® © 3 10

Presley v. Commonwealth, 185 Va,

38 S o E. 2d 476 . . . . . . .

261,

e s» ® * 12

Rollins Vo Shannon, 292 F, Supp. 580 . 16

SiIvey v. Johnston, 193 Va. 677,

70 S ,E , 2d 280 . . . . . . . ® ® o 12

Smith Vo Commonwealth, 192 v a - 453,

65 S.E, 2d 528 , . ............. .. It

Spratley v. Commonwealth, 154 Va

152 S.E. 362

. 854,

Terminiello v, Chicago, 337 u.S. 1,

69 S.Ct. 894, 93 L, ed 1131 , . . , 19,22

Thomas v. Danville, 207 Va, 656,

152 S,E, 265 » . . . . , . , , . !9

T h cmp son y L c u j s v i I is, 36 7 US. 199 .

80 S.Ct. 624. 4 L , ed • 3 65 4 ,

80 A . L . R . i d , 8 5 5 »• * * i> c 1 0,

University Committee to Er V pS '• ■?

Viet Nam v. Gunn, 289 F, Supp , 469 „ , 19

Ware v, Nichols, .266 F , Supp. £6 4 , ,

7: cher Author1 ties

0, S, Constitution, Amendment I , 3,17,21,24

U. S , Constitution, Amendment XIV

7,10,14,17,18,25

Acts of Va. Assembly, 1968, Ch, 460,

Page

Code of Virginia:

§18 o1-87 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

§18=1-227 . . . . = . i . o . . . ■ .. 24

§18 = 1-237 ,, o . . . . . . 24

§18=1-254 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

§18o1-254 =1(c> . . . . . . . . . . 7,14,17

§18 o1-254 o 4 24

§18=1-254.8 24

Ordinance' of City of Richmond #68-79-44

(April 7 r 1968) . . . . . . . . .10,11/App.l

Code of District of Columbia, §22-1107. 25

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

At Richmond

Record No.* 7213

ALVIN HALL,

Plaintiff-in-Error

v.

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Defendant-in-Error

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFF-IN-ERROR

STATEMENT OF THE MATERIAL PROCEEDINGS

IN THE LOWER COURT

Upon appeal from a Police Court conviction

on a warrant charging that the defendant did

unlawfully be disorderly and did disturb the

peace in a riotous manner, the matter came on

for trial de novo in the Hustings Court and

the warrant was amended to charge that the

defendant "did unlawfully assemble without

the authority of law and for the purpose of

2

disturbing the peace or exciting public alarm

or disorder," to which amended charge the

defendant plead not guilty.

At the conclusion of the testimony for the

Commonwealth, the defendant moved to strike

the evidence (1) on the ground that the evi

dence was insufficient and (2) on the ground

that First Amendment freedoms are impermissably

invaded by that part of the Virginia statute

which is alleged to have been violated. The

motion was overruled and the defendant excepted.

The defendant then introduced evidence show

ing that his case coincided with the hypotheses

of innocence which he had previously contended

the Cpmmonwealth had failed to. exclude. There

upon the defendant renewed his motion to strike

the evidence which motion was overruled and

exception was saved.

Exception was saved to the granting of

instruction number 4 by which the jurors were

told that the credibility of witnesses is a

question exclusively for the jury; the objec

tion being founded upon the circumstance that

3

there was no conflict in the evidence.

Exception was saved to instruction number 6

which stated the penalty for participating in

an assembly "without the authority of law and

for the purpose of disturbing the peace or

exciting public alarm or disorder", the

suggested necessity of "authority of law" for

an assembly being an impermissable impinge

ment upon First Amendment freedoms, and the

proscribed purpose of "disturbing the peace or

exciting public alarm or disorder" being too

vague to meet constitutional requirements of

due process .

Exception was saved to the denial of the

motion to set aside the verdict of the jury

on the grounds previously urged. The defend

ant was sentenced in accordance with the ver

dict of the jury,

A motion that execution of the sentence be

suspended to permit this application for a

writ of error was granted. Notice of appeal

was filed on July 19, 1968. Designation of

the parts of the record to be printed was

4

filed on August 28, 196 8.,

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

On April 8, 1968, police officers of the City

of Richmond were on special duty to contain or

control disturbances which followed the April *

4 assassination of Dr, Martin Luther King, Jr,,

in Memphis, Tennessee, Police Sergeant Conner

was one of two sergeants in charge of two squads

consisting of about eighteen officers. In a

school bus they left the police substation at

9th and Marshall Streets between 8:00 and 9:00

P.Mo, pursuant to a call, and proceeded west on

Broad Street. As they approached Third Street,

Sergeant Conner saw a group of persons on the

north side of Broad Street moving eastwardly,

approaching Second Street. The bus came to a

stop in the two hundred block of Broad Street

(between Third and Second Streets). As the

group under observation crossed Second Street

the police officers left the bus. People in

the group were cursing loudly, screaming, shout

ing obscenities, darting in and out between the

automobiles and parking meters, and taking up

5

the entire-; sidewalk.

Sergeant Conner and the other two officers

who testified were a part of the squad which

formed a line across the sidewalk stopping the

eastwardly movement of the group under surveil

lance (R, 9, 14 f 18, 19). State Troopers

(none of whom testified) were "more or less

following the group and some were on the other

corner of Second and Broad Streets" (R. 11).

No officer who testified was ever any closer

to Second Street.than the Surplus Store

(R. 10), number 208 East Broad (R> 16), the

school bus which brought them to the scene hav

ing stopped in the bus stop "on the east end

of the block" (R„ 18).

The defendant was captured within the cor

don of police officers.

Several persons thus captured dropped

"brickbats, a couple of bottles, a pepsi-cola

bottle and some other type bottle, a couple of

sticks and two knives" (R. 9).

At the time that this group was crossing

Second Street, the defendant was walking south-

6

wardiy on Second Street In. the direction of

Broad Street, When he got to Broad Street, he

turned to his left to proceed eastwardly on

Broad passing some State Troopers who were on

the corner at the time. The crowd which had

crossed Second Street was then in front of him,

proceeding eastwardly on Broad Street. The

State Troopers closed in from the west, join

ing the City police on the east, thus complet

ing the cordon, (R. 26-29)

THE ASSIGNMENTS OF ERROR

1. On the motions to strike the evidence and

on the motion to set aside the verdict, the

court erred in ruling that there was a showing

that the defendant was not walking southwardly

on Second Street toward its intersection with

Broad at the time when the alleged unlawful

assembly, proceeding eastwardly on Broad Street,

was crossing Second Street,

2c There having been no material conflict in

the evidence, the Court erred in instructing

the jury that they were the judges of the credi

bility of the witnesses; and thereby the defend-

7

ant was denied due process of law in vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

3o On the motion to strike the evidence

and again in granting instruction number 6,

the Court erred in ruling that First and

Fourteenth Amendment rights are not violated

by so much of Code Section 18*1-254,1 as

proscribes an assembly of three or more

persons without authority of law and for

the purpose of disturbing the peace or

exciting public alarm or disorder.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I

Is there any evidence that the defendant

was with, the group before it crossed Second

Street or that thereafter he adopted its

purpose as his own?

II

May any trier of fact arbitarily disregard

uncontradicted testimony which is not inher

ently incredible?

III

May citizens be required to forego the

8

right of peaceable assembly for fear that its

exercise may disturb the peace or excite public

alarm or disorder?

IV

Absent observed overt, acts calculated to dis

turb the peace or excite public alarm or dis-

order, may an assembly be forbidden because

police officers believe such to be its purpose?

ARGUMENT

I

The Evidence Does Not Show That The

Defendant Was a Part Of The Assembly

The three witness for the Commonwealth, all

Richmond police officers, testified that they

were a part of a squad which alighted from the

bus in the two hundred block of East Broad

Street and formed a line across the sidewalk,

facing westwardly toward Second Street for the

purpose of intercepting the group which had just

crossed Second Street, proceeding eastwardly0

(R. 8-9, 14, 17) These officers did not get up

as far as Second Street (R. 12).

The defendant showed that as the group was

9

crossing Second Street he was proceeding

southwardly on Second Street, towards Broad

and that,, after the group had crossed, he

turned to his left and proceeded southwardly

on Broad behind the group (R. 26-29).

No witness was called who was on the west

side of the group or who had been stationed

at Second Street or who had the responsibil

ity of insuring that no innocent person walk

ing down Second Street and turning into Broad

would have been swept into the police cordon.

No person was called to testify who was in

position to know whether this defendant was

or was not walking down Second Street when

the group crossed Second Street.

Office Burley testified that this defendant

was in the "group" of persons who were sur

rounded by the police. (R. 15) But there is

no testimony to show that the defendant was

one of the "group of disorderly persons"

which the police had been dispatched to

investigate

The evidence to connect this defendant with

10

the original group of individuals whom the

police were dispatched to investigate is

entirely circumstantial. The circumstances have-

been adequately explained. It is well settled

that such evidence to be sufficient to support

a conviction must not only be consistent with

guilt but must be inconsistent with innocence.

Gamble v. Commonwealth, 161 Va, 1024, 170 S.E.

561 (1933), Powers v. Commonwealth, 182 Va.

669, 30 S.E, 2d 22 (1944), Smith v. Commonwealth,

192 Va. 453, 65 S.E. 2d 528 (1951).

The net result is that the defendant has been

convicted without evidence of his guilt in vio

lation of the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. See Thompson v. Louisville

362 U.S. 199,80 S.Ct. 624, 4 L. ed 2d 654, 80

A.L.R. 2d 1355 (1960).

The realities of the situation at the time of

the arrest can better be understood if reference

is made to an Ordinance-— No, 68-79-44--adopted

April 7, 1968 by the Council of the City of

Richmond as emergency legislation by which the

Chief of the Bureau of Police, or his designee,

11

was "authorized and empowered to regulate,

restrict or prohibit any assembly of persons

or the movement of persons and vehicles in

the said city, including "the banning of

persons and/or vehicles from said streets

during such hours as said Chief of Police or

his designate may deem proper in the neces

sary protection of persons and property."

The. preamble to the ordinance shows the

Council's concern for the "disorderly conduct,

disturbances and disorderly assemblages in

public places within this city which consti

tute a danger to the safety, health, peace,

good order and welfare of the citizens of

this city * * * [which] commenced on the

evening of Saturday, April 6, 1968" (two days

following Dr. King’s assassination. An

attested copy of said ordinance is appended

hereto„

Pursuant to this ordinance, the police

removed Negroes from the streets and charged

the individuals thus arrested with behaving

in a disorderly manner in violation of

12

Section 18,1-254 of the Code of Virginia, the

April 2, 1968 emergency repeal of which had

escaped their attention, In the Hustings Court,

as in the instant case, the warrants were

amended to charge "unlawful assembly,"

II

The Jury May Not Arbitrarily Disregard

The Uncontradicted Testimony Of Unimpeached

Witnesses Which Is Not Inherently Incredible

The general rule is that where unimpeached

witnesses testify positively to a fact and are

uncontradicted, the jury is not at liberty to

discredit their testimony, Presley v. Common

wealth, 185 Va. 261, 266, 38 S.E. 2d 476 (1946);

Metropolitan Life Insurance v, Botto, 153 Va,

468, 480, 143 S.E., 625, 154 S.E, 603 (1928).

Epperson & Carter v, DeJarnette, 164 Va, 482,

485-6, 180 S.E. 412 (1935). Silvey v. Johnston,

193 Va. 677, 681, 70 S.E. 2d 280 (1952)„

In Presley v, Commonwealth, supra., the defend

ant was convicted of second degree murder

although he had introduced evidence of self-

defense, which was supported by investigation.

In reversing the conviction, it was held that

13

the jury's disregard of such uncontradicted

evidence was arbitary. It was also held that

the defendant's contention, that the victim

believed that the defendant had consorted

with his wife and had told other witnesses

that he would kill the defendant, was not.

an inherently improbable story.

In the case at bar, there was no material

conflict in the evidence and the defendant's

story was not. inherently incredible. The

best the Commonwealth could establish was

that the. defendant was transported to the

police station with the members of the

group the police had surrounded.

Mere presence at a place where a crime is

being committed, even if the defendant

knows it is being coirimi tted, is not enough

to render him guilty of its commission.

Spratley v. Commonwealth, 154 Va. 854, 860,

152 S.E. 36.2 (1930) .

The jury was not told by the Court that

the evidence was insufficient to support

a finding of guilt. The jury was told that

14

the credibility of witnessess is a question

exclusively for the jury. Thus, the jury was

told that the defendant might be convicted if

the jury chose arbitrarily to disregard his

testimony, As a result, the defendant has been

convicted without evidence of his guilt and in

violation of the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment, Thompson v. Louisville, supra.

Ill

Citizens May Not Be Impelled To Forego

The Exercise of First Amendment Rights

For Fear Of Violating An Unclear Law

A

Only One Definition Is Challenged

Having read the brief on behalf of the Common

wealth filed by the Attorney General in James

Leon Harrison, Petitioner,'v. W. K. Cummingham,

Jr., Director of the Division of Corrections,

Respondent'(Record No. 7234), we seek to

clarify the question here by putting to the

side contentions which we do not advance in this

case. We do not here attack so much of Code

§18.1-254.1(c) as defines unlawful assembly,

viz;

15

"Whenever three or more persons assemble

with the common intent or with means and

preparations to do an unlawful act which

would be riot if actually committed, but

do not act toward the commission thereof."

That definition, by its incorporation of the

statutory definition of "riot", requires a

show of unlawful force or a present threat of

unlawful violence as an element of unlawful

as s emb ly .

Similarly, we do not attack the common law

concept of unlawful assembly. The author-

ities which purport to define the common law

crime of unlawful assembly clearly indicate

that a demonstrable intention of making an

unlawful use of force and violence is an

indispensable element of that, crime.

The case of Heard v. Rizzo, 281 F. Supp.

720 (E.D. Pa,, 1968), sustained Pennsylvania's

statutory proscription of unlawful assembly.

Following the practice of the Pennsylvania

courts of defining common law terms not other

wise defined in a statute by referring to an

established meaning at common law, the

Federal court quoted Black's Law Dictionary

16

definition of unlawful assembly, viz:

"The meeting together of three or more per

sons to the disturbance of the public peace,

and with the intention of co-operating in

the forcible and violent execution of some

unlawful enterpriseI * * * To constitute

offense it must appear that there was

common intent of persons assembled to

attain purpose, whether lawful or unlawful,

by commission, of act_s of intimidation and

disorder likely to produce danger to peace

of neighborhood, and actually tending to

inspire courageous persons with well-

grounded fear of serious breaches of

public peace," [Emphasis supplied] (281

F. Sapp . at 740)

In Rollins v, Shannon, 292 F, Supp. 580 (E.D,

Mo., 1968), the statute under review provided:

"If three or more persons shall assemble

together with the intent * * * to do any

unlawful act, with force or violence,

against the person or property of another,

or against the peace or to the-tsrrorw-of the

people, such persons * * * shall be deemed

guilty of an unlawful*' assembly *" * * "

[Emphasis supplied] (292 F. Supp. at 589).

In the case of Devine, v. Wood, 2 86 F. Supp.

102 (M.D. Ala. 1968), the plaintiff challenged

a statute which, in part, read:

"If two or more persons meet together to

'commit a breach of the peace, or to do any

other unlawful act, each * * * shall * * .*

be punished *.* (286 F. Supp. at 104)

This statute was viewed in the light of Ala

bama's judicial holding that the defendants, to

be punishable, must

"assemble in such a manner, or so conduct

themselves when assembled, as to cause

persons in the neighborhood of such

assembly to fear on reasonable grounds

that the persons so assembled would com

mit a breach of the peace or provoke

others to do so," [Emphasis supplied]

(286 F. Suppi at 105)

We do not question the right of the state

to protect citizens and their properties

against the unlawful use or threat of violence

as is the purpose of the statutes above men

tioned, They are unlike the definition

challenged here,

B

The Constitutional Privilege Transcends

The State Interest

Insofar as Code §18.1-254.1(c) defines an

unlawful assembly as "whenever three or more

persons assemble without authority of law and

for the purpose of disturbing the peace or

exciting public alarm or disorder," the

statute violates the Due Process Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States as it incorporates the

First Amendment and further, as applied in

18

this case, the statute violates the Privileges

and Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

In Hague v. C ,1 ,0, 307 U.S. 496, 59 S.Ct. 9 54,

83 L. ed 1423, (1939), it was recognized that

the privileges of citizens to use the public

streets is of ancient origin, and one that

inheres in citizenship, has the protection of

the Fourteenth Amendment, and "must not, in the

guise of regulation, be abridged or denied."

(307 U.S. at 515-16). The challenged statutory

definition of unlawful assembly goes further

than the ordinance in Hague. It charges a citi

zen to obtain "authority of law” (a permit)

before assembling with two or more others at

any place, public or private; otherwise they

will have no assurance against molestation or

arrest by officers who for any reason or for no

reason may assume that the purpose of the

assembly is to disturb the peace or excite

public alarm or disorder, A publicly advertised

but unlicensed mass meeting called for the

announced purpose of launching public protest

19

demonstrations would clearly be within the

reach of the statute.

This branch of the case is controled by

1/

Thomas v. City of Danville, 207 Va. 656,

662-3, 152 S.E, 2d 265 (1967). Items 4 and 6

of the injunction then, under review forbade

the defendants

"from creating * * * noises * * * designed

to upset the peace and tranquility of the

community * * * [andj from * * * holding

unlawful assemblies such as to unreasonably

disturb or alarm the public * * *,

The statute now under review proscribes an

assembly if it has

"purpose of disturbing the peace or

exciting public alarm or disorder."

On the authority of Terminiello v. City of

Chicago, 337 U,S. 1, 69 S.Ct. 894, 93 L ed,

1131 (1949) this Court struck down the judi

cial prohibitions because the subjects

thereof did not constitute "a serious substan

tive evil that rises far above public incon

venience , annoyance, or unrest". (207 Va. at

•L/Thomas was cited and followed in University

Committee to End War in Viet Mam v. Gunn, 289

F. Supp. 469,475 (W.D.Tex. 1968), quod vide.

20

663) [Emphasis by the Court] The only material

difference between the Danville injunction and

the Virginia statute is that the injunction

purported to forbid acts which are constitution

ally privileged and the statute purports to pro

scribe an unexecuted purpose of committing such

acts o

C

The Statute Provides No Standard Whereby

The Purpose Of An Assembly

May Be Ascertained

Inasmuch as it proscribes assemblies held for

the purpose of disturbing the peace or exciting

public alarm or disorder, the statute may be

violated before any disturbing or exciting act,

has in fact been committed. It does not purport

to say how, under such circumstances, the

existence of such purpose may be ascertained by

arresting officers, by trial judges or juries,

or by appellate courts. Citizens who may be

assembled for a lawful purpose can not know what

indicia of unlawful purpose the statute requires

them to avoid. If, for example, the statute

drew an inference of forbidden purpose from the

21

carrying of firearms or the wearing of red

armbands by three or more persons assembled

(as Code §18.1-87 draws a presumption of

unlawful intent from the mere possession of

burglarious tools), citizens could exercise

their First Amendment right of assembly with

impunity from arrest by not carrying firearms

or wearing red armbands. See Giaecio v.

Pennsylvania, 382 U,S. 399, 15 L. ed 2nd 447,

86 S. Ct. 518 (1966) , and Lanzetta v. New

Jersey, 306 U.S. 451, 59 S. Ct. 618, 83 L. ed

888(1939).

D

The Statute Is Unconstitutionally Vague

"Vague laws in any area suffer a constitu

tionally infirmity. When. First Amendment

rights are involed, we look even more closely

lest, under the guise of regulating conduct

that is reachable by the police power, free

dom of speech or of the press suffer. We

said in Cantwell v. Connecticut, * * *r that

such a law must be 'narrowly drawn to pre

vent the supposed evil' *,* * and that a

22

conviction for an utterance "based on a common-

law concept of the most general and undefined

nature* * * * could not stand", (Ashton v...

Kentucky, 384 U.S. 195, 200-1, 16 L. Ed 2d 469,

86 S.Ct. 1407 (1966).

The terms "disturbing the peace" and "excit

ing public alarm or disorder", as used in the

instant statute, suffer the same infirmity of

overbreadth which has caused courts to inval

idate legislation because it was susceptible

of being read as impinging upon First Amend

ment freedomso Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310

UaS, 296, 60 S. Ct. 900, 84 L, ed 1213 (1940)

(breach of the peace conviction based on a com

mon law concept), Terminlello v. City of

Chicago, supra, (disorderly conduct tending tof'

a breach of the peace)„ Edwards v. South

Carolina, 372 U.S. 229, 9 L. ed 2d 697, 83 S.Ct.

680 (1963) (common law breach of the peace).

Cox v, Louisiana, 379 U.S, 536, 544, 13 L. ed 2d

471, 85 S. Ct. 453 (1965) (dongregating "with

intent to provoke a breach of the peace, or

under circumstances such that a breach of the

peace may-be.occasioned thereby" and failing

to disperse when ordered by police,) Ashton

v. Kentucky, supra, (Criminal libel defined

as "any writing calculated to creat disturb

ances of the peace"), Ware v. Nichols, 266

F. Supp, 564 (N.D Miss, 1967) (assemble for

the purpose of advocating, teaching, etc.)

Carmichael v. Allen, 267 F. Supp. 985 (N. D,

Ga. 1966) ("acts in a violent, turbulent,

quarrelsome, boisterous, indecent or dis

orderly manner * * * or to do anything tend

ing to disturb the good order, morals, peace

or dignity of the City".) Baker v. Binder,

274 F. Supp, 658, 661 (W.D. Ky, 1967) ("No

two or more persons shall * * * go forth for

the purpose of intimidating, alarming, dis

turbing or injuring any person.")

IV

There Was No Overt Act Justifying Arrest.

The police officers observed a moving crowd

of individuals, some of whom were shouting

obscenities and "using profane language."

The General Assembly has sought to ban

24

obscene publications and' transcriptions - (Code

§18al-227 et seq,) but not- the-oral use- of Saxon-

words- now : considered vulgar; although Code

§18.1-237 authorizes a fine not exceeding $25

if any person arrived at the age of discretion

"profanely curse or swear" in public. (By way

of contrast, see §22-1107 of the Code of the

District of Columbia which forbids persons "to

curse, swear, or make use of any profane lan

guage or indecent or obscene words" in any public

place.)

If language allegedly used (but not repeated

in the record) was not in fact profane, the

persons arrested were under the umbrella of the

speech aspect of the First Amendment, unaffected

by any attempted statutory proscription.

In this latter event, if the police were to

take any action, they were charged by Code §18.1-

254.8 to "go among the persons assembled or as

near them as possible and command them in the

name of the State immediately to disperse"; and

those who failed to do so may have been subject

to punishment as provided in Code §18.1-254,4.

25

It could not be consonant with Fourteenth

Amendment equal protection or due process

concepts to allow the police an arbitrary

discretion to arrest for unlawful assembly

without a prior order to disperse in some

cases and in others to arrest only for fail

ure to comply with an order to disperse.

If the obscenities were not considered

punishable as such and if, in fact, there was

no profanity, then there should have been no

arrest because the assembly appears to have

been otherwise peaceable. Unless and until

it had commited some overt act calculated to

disturb the peace, the assembly was constitu

tionally privileged.

Once the shouted obscenities are viewed in

any proper perspective, we see the police

observing a boisterous or noisy but otherwise

unoffending crowd moving eastwardly on Broad

Street, about 9:00 o'clock, on a Monday night,

disturbing no one, as far as this record shows.

Having been authorized by the April 7, 1968

ordinance (copy of which is appended hereto)

26

to regulate, restrict or prohibit any assembly

of persons and to ban persons from the streets,

and knowing nothing of Chapter 460 of the Acts

of Assembly, 1968, the police proceeded first

to remove this group of Negroes from the street

and thereafter to charge its members with dis

orderly conduct.

The statute now said to have been violated

purports to punish the purpose which the State

now attributes to the individuals in the

assembly. Nothing in the statute indicates

how the existence of such purpose is to be

ascertained by police officers, by jurors, or

by reviewing courts. If the statute may be

enforced as demonstrated by this record, no

assembly may withstand the displeasure of the

police department; and the related protections

of the First and Fourteenth Amendments become

meaningless.

CONCLUSION

This case classically demonstrates that the

Court should strike down the challenged defi

nition of unlawful assembly. Because it dis-

27

peases with objective proof of wrong doing,,

this definition of unlawful assembly was

employed by the Commonwealth's Attorney to

facilitate conviction of all who had been

arrested, including this plaintiff-in-error

whose presence at or near the scene of the

mass arrest was entirely fortuitous.

The police, the Commonwealth's Attorney,

the Police Court, the jury and the Hustings

Court, each in turn, disregarded the evidence

which adequately buttressed the presumption

of innocence and discredited the evidence

which proved innocence. They conclusively

presumed this individual to be guilty from

the mere fact that he was in the vicinity

where others of his race were engaged in

untoward conduct. As a result, he was

required to obtain surety, stand trial in

the Police Court, retain counsel for trial

in the Hustings Court, and later to procure

assistance for defraying the cost of the

transcript and the cost for printing the

record. The entire process illustrates

28

unjust oppression; and its repetition against

other persons similarly conditioned should be

forestalled here and nowc

We do not argue against a law which commands

an officer to arrest for wrongdoing which he has

seen. But we earnestly submit that no statute

should stand which subjects citizens to arrest

for what an officer believes to be their purpose.

Respectfully submitted,

S. W. TUCKER

Of Counsel

S. W. TUCKER

HAROLD Me MARSH

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiff-in-Error

C E R T I F I C A T E

I certify that three copies hereof were

delivered to the office of the Attorney General

of Virginia on or before the date of filing.

September 19 69,

App. 1

AN ORDINANCE-No. 68-79-44

(Adopted April 7, 1968)

To empower and authorize the Chief of Bureau

of Police or his designate to make regu

lations for the preservation of the

safety, health, peace, good order, comfort,

convenience, morals and welfare of the

city of Richmond and its inhabitants and

to provide penalties for violation thereof.

WHEREAS, there has been disorderly conduct,

disturbances, and disorderly assemblages in

public places within this city.which consti

tute a danger to the safety, health, peace,

good order and welfare of the citizens of

this city, and,

WHEREAS, the aforesaid acts commenced on the

evening of Saturday, April 6, 1968, and have

persisted all during the night and continue

to exist which present a clear and present

danger to the citizens of this City, and their

property; Now, Therefore,

The City of Richmond Hereby Ordains:

That the Chief of the Bureau of Police, or

his designate, is hereby authorized and

empowered to regulate, restrict or prohibit

any assembly of persons or the movement of

persons and vehicles in the said city and

said power and authorization shall include

the banning of persons and/or vehicles from

said streets during such hours as said Chief

of Police or his designate may deem proper

in the necessary protection of persons and

property.

Any person or persons violating any pro

vision of said regulation, restriction, pro

hibition or curfew shall upon conviction

thereof be punished pursuant to §1-6 of

App» 2

Richmc '£,a City ;Code of 1963* as -amended=

This ordinance shall be force and eff

inured!. UP'on passage.