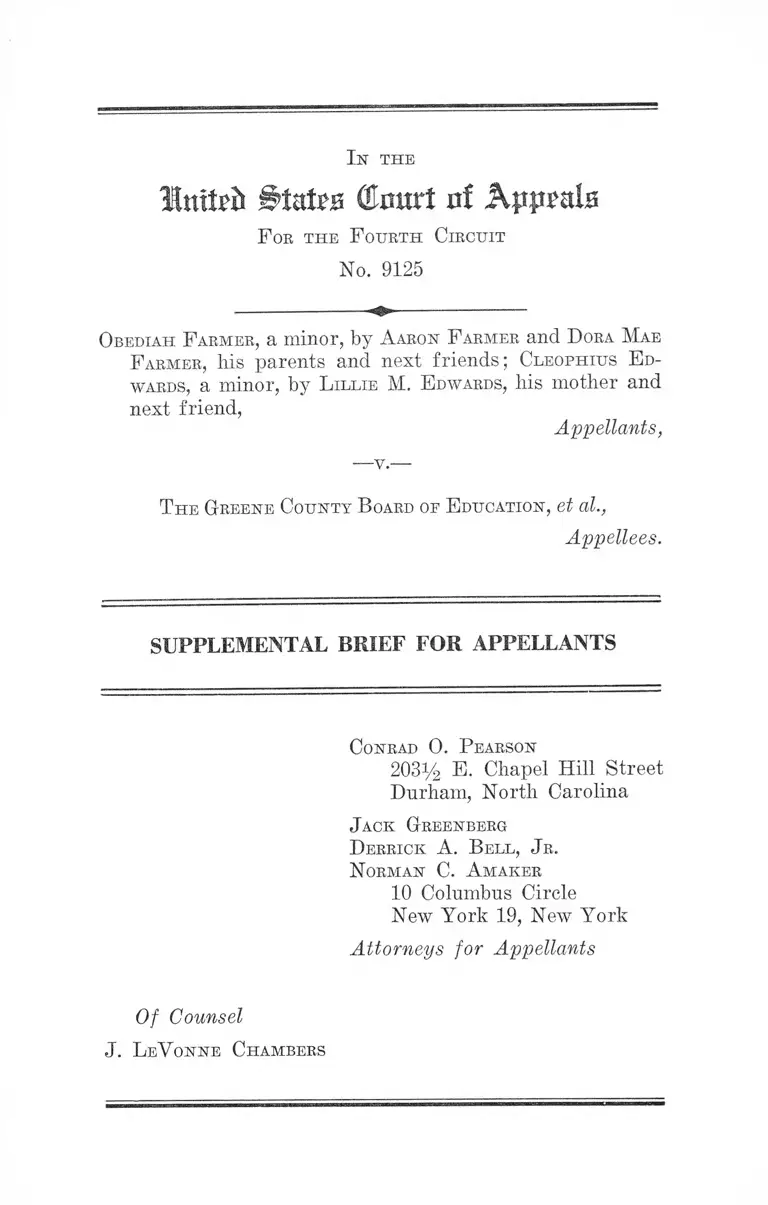

Farmer v. Greene County Board of Education Supplemental Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Farmer v. Greene County Board of Education Supplemental Brief for Appellants, 1963. da3c016c-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c6b8e6a4-77e5-4ef5-8352-ab6c20e970cb/farmer-v-greene-county-board-of-education-supplemental-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

llnxUb Cmtrt uf Appeals

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 9125

In th e

Obediah. F armer, a minor, by A aron F armer and D ora Mae

F armer, his parents and next friends; Cleophius E d

wards, a minor, by L illie M. E dwards, his mother and

next friend,

Appellants,

T he Greene County B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Appellees.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Conrad 0 . P earson

2031/2 E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J ack Greenberg

Derrick A. Bell, Jr.

Norman C. A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

Of Counsel

J. LeV onnb Chambers

Preliminary Statement

A rgument :

I N D E X

PAGE

1

I. It Was Error for the Court Below to Deny In

junctive Eelief to Appellants for Failure to

Exhaust Administrative Remedies, Because Ex

haustion of a State Remedy Is Not a Prerequisite

to Invocation of a Federal Remedy in the Federal

Courts.............................................. ........................... 2

II. It Was Error for the Court Below to Deny

Injunctive Relief to Appellants for Failure to

Exhaust Administrative Remedies, Because Ap

pellants Have No Administrative Remedies ..... 3

Conclusion............................................................................ 10

T able of Cases:

Armstrong v. Board of Education of the City of Bir

mingham, 323 F. 2d 333 (5th Cir. 1963) ................... 2, 9

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862

(5th Cir. 1962) ............................... .................. ............... 9

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Brax

ton, ------ F. 2d ------- (No. 20294, 5th Cir., January 10,

1964) ............ ....... ..... ................ ............. .......... ..... ........ 4

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483 (1954) 4

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) ..... 4

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir. 1962) ................. ............. ......... ...... ......... ...... 9

11

PAGE

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956) ....... 6

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ............................... 4

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

------ 2d ■—— (No. 20824, 5th Cir., February 13,

1964) .................................................................................. 9

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763

(5th Cir. 1959) ............................................. -----............... 9,10

Gill v. Concord City Board of Education, M. D. N. C.,

No. C-223-5-63 (February 20, 1964) ............................... 2

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg, 321

F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) ........................-..................... 4

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962) .......6,10

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370

(5th Cir. 1960) ........................................ -...................... 9

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County, 305

F. 2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962) .............................................. 5

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668

(1963) ................................................................................2, 3, 4

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961) ............................... 2

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of

Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) ....................... 7

Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963) .......................

Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963) ..... ......... 9

Isr t h e

Itttteit BtnUb Court of Appeals

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 9125

Obediah F armer, a minor, by A aron F armer and D ora Mae

F armer, his parents and next friends; Cleophius E d

wards, a minor, by L illie M. E dwards, his mother and

next friend,

Appellants,

—v.—

T he Greene County B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Appellees.

--------------------->♦”--------------- ------

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Preliminary Statement

Appellants, by this supplemental brief, wish to focus

more sharply the position asserted in their earlier brief.

It was there maintained that the remedy provided by the

North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act is futile and useless.

It will be shown here that the Act is irrelevant to the relief

appellants seek, namely, enforcement of their right to at

tend a desegregated school system. Moreover, even if the

Act were relevant to the relief they seek, resort to it is not

prerequisite to invoking federal jurisdiction.

2

ARGUMENT

I

It Was Error for the Court Below to Deny Injunctive

Relief to Appellants for Failure to Exhaust Administra

tive Remedies, Because Exhaustion of a State Remedy

Is Not a Prerequisite to Invocation of a Federal Remedy

in the Federal Courts.

Appellants seek enforcement of their federal constitu

tional right to attend a desegregated public school system.

This right may not be defeated because relief was not

first sought under state law. Federal courts exist to en

force federal rights, and need not defer to state processes.

This was made perfectly plain by the United States Su

preme Court in McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S.

668 (1963). There the Court said, quoting Monroe v. Pape,

365 U. S. 167, 183 (1961):

It is no answer that the State has a law which if en

forced would give relief. The federal remedy is sup

plementary to the state remedy, and the latter need

not be first sought and refused before the federal one

is invoked.

As was said in Armstrong v. Board of Education of the

City of Birmingham, 323 F. 2d 333, 336 (5th Cir. 1963),

McNesse and Monroe v. Pape “put beyond debate the prop

osition that, in a school desegregation case, it is not neces

sary to exhaust state administrative remedies before seek

ing relief in the federal courts.” Accord, Gill v. Concord

City Board of Education, M. D. N. C., No. C-223-5-63, Mo

tion to dismiss complaint denied February 20, 1964 (Stan

ley, J.).

3

The suggestion that McNeese, supra, has reference only

to an inadequate Illinois administrative procedure is re

futed by reading the opinion which, as shown above, clearly

rejects the argument that exhaustion of remedies provided

by a state law, even if adequate, is prerequisite to federal

jurisdiction. Moreover, as Justice Harlan pointed out in

dissent, the majority opinion would reach the administra

tive remedies provided by North Carolina law as well as

those in Illinois.

ARGUMENT

II

It Was E rror fo r the Court Below to Deny Injunctive

R elief to Appellants fo r Failure to Exhaust Administra

tive Rem edies, Because Appellants Have No Administra

tive Rem edies.

The court below denied appellants’ motion for a pre

liminary injunction apparently on the ground that appel

lants failed to exhaust administrative remedies under the

North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act (224a-231a).

This was certainly error, because appellants have no ad

ministrative remedies under the Act.

This is clear from a consideration of the relief appellants

seek. Appellants seek not merely their own admission to

white public schools in Greene County. Appellants seek

complete desegregation of the Greene County public school

system in accordance with the mandate of the United States

Supreme Court (la-12a).

The North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act cannot pro

vide appellants the relief they seek. The Act offers no pro

tection for the constitutional right to attend a desegregated

4

school system. The Act is in no sense a vehicle for de

segregation. In fact, as will be shown, the Act serves as a

cover for the perpetuation of segregation in the Greene

County school system. Therefore it is unthinkable that

appellants should be compelled to submit to the sterile ritu

als commanded by the Act before being permitted to sue

for protection of their constitutional rights in federal

court. McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668

(1963).

One hundred percent segregation and the Pupil Enroll

ment Act coexist comfortably in Greene County (94a-95a;

121a-130a; 200a-201a).1 No desegregation has ever oc

curred under the Act. Those who have sought to employ the

Act as an instrument of desegregation have found it a

weak reed upon which to lean (183a).

Nor is it merely coincidental that segregation has con

tinued to thrive in the climate of the Act. The design of the

Act serves to thwart desegregation, or at the very least,

to confine desegregation to the token level. The Act ac

complishes this by shifting the administrative burden to

desegregate the schools from the school boards, where it

rightfully belongs,2 to the individual child. The Act dic

tates that the implementation of the United States Supreme

Court’s mandate must await the outcome of a contest be

tween the individual school child and state power. The

contest is unequal. The child must secure and prepare a

transfer application and must file it within a short time

1 This includes segregation of teachers as well as pupils. Desegre

gation of teachers is required by Jackson v. School Board of the

City of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230, 233 (4th Cir. 1963) ; Board of

Public Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton, ------ F. 2d ——-

(No. 20294, 5th Cir., January 10, 1964.)

2 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ; Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) ; Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1 (1958).

5

period (252a, 256a). Once that brief period has passed he

is foreclosed for the rest of the year. The school board may

merely reject the application, and give no specific reason

for doing so (182a-183a). The child must then pursue a

tortuous path through the procedures of appeal and hear

ing with little prospect of relief. The process has been

aptly characterized by this Court as an “unnegotiable ob

stacle course” (309 F. 2d at 628).

In summary, the Act, functioning as intended, makes

more than token desegregation almost impossible, places

the burden of altering the status quo (the biracial school

system) upon individual Negro pupils and their parents,

establishes a procedure which is difficult and time-consum

ing to complete, and prescribes standards so varied and

vague that it is extremely difficult to prove that any in

dividual denial is attributable to racial considerations.

Neither in theory nor in practice is the Act a plan for

desegregation in accordance with the mandate of the United

States Supreme Court. Quite the contrary. It is, there

fore, small wonder that this Court condemned the exhaus

tion of remedies requirement in Marsh v. County School

tBoard of Roanoke County, 305 F. 2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962),

saying:

To insist, as a prerequisite to granting relief against

discriminatory practices, that the plaintiffs first pass

through the very procedures that are discriminatory

would be to require an exercise in futility. 305 F. 2d

at 98.

That, in sum, is appellants’ position here: That, in order

to secure federal constitutional rights, it is futile to comply

with the provisions of a state statute which, insofar as it

bears any relation to the federal constitutional rights sought

to be enforced, serves to frustrate these rights. Put an

6

other way, appellants’ position is that the indulgence of

applications for transfer from initial assignments based

on race does not make the Act a desegregation plan, and,

since the Act is not a desegregation plan, it is irrelevant to

the enforcement of ajjpellants’ right to attend a desegre

gated public school system.

In Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962),

this Court served notice that the Act, in practice, is any

thing but a plan for desegregation. There, as here, a

school board which operated a totally segregated system

sought, in a federal suit, to take shelter behind the exhaus

tion of remedies requirement of the North Carolina Pupil

Enrollment Act. This Court brushed aside the defense,

saying:

[W]hen an administrative remedy respecting school

assignments and transfers, however fair upon its face,

has, in practice, been employed principally as a means

of perpetuation of discrimination and of denial of

constitutionally protected rights, we have consistently

held it inadequate. A remedy so administered, need

not be exhausted or pursued before resort to the courts

for enforcement of the protected rights. 309 F. 2d at

628.

It is now time for this Court to declare that the Act,

in theory as well as practice, is inadequate to protect

federal constitutional rights in a manner consistent with

the mandate of the United States Supreme Court. Specifi

cally, this calls for the explicit overruling of Carson v.

War lick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956), which held that the

Act is a valid plan for desegregation on its face. School

children need not apply for that to which they are entitled

as of right.

7

This Court should make clear beyond peradventure that

compliance with this state statute, which does not and cannot

enforce federal constitutional rights, is not a prerequisite

to the enforcement of federal constitutional rights in the

Federal Courts.

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) points the way for

decision in this case. There, as here, the school board

operated a biracial school system. There, as here, plain

tiffs prayed for an order enjoining the school board from

operating a biracial school system or, in the alternative,

for an order to the board to submit a plan for the reorgani

zation of the schools on a unitary nonracial basis. There,

as here, the defendant board sought to take refuge behind

a pupil placement statute and claimed that the plaintiffs

should have exhausted putative remedies under the stat

ute. The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit held that

the pupil placement statute was no plan for desegregation

and that, therefore, its provisions could not impede plain

tiffs in the enforcement in federal court of their federal

right to attend a desegregated public school system.

Preliminarily, the court set forth the constitutional re

quirement, 302 F. 2d at 823:

Minimal requirements for non-racial schools are

geographic zoning, according to the capacity and fa

cilities of the buildings and admission to a school

according to residence as a matter of right. “ Obvi

ously the maintenance of a dual system of attendance

areas based on race offends the constitutional rights

of the plaintiffs and others similarly situated and

cannot be tolerated.” Jones v. School Board of City

of Alexandria, Virginia, 278 F. 2d 72, 76, C. A. 4.

Next, the court described the theory and practice of the

pupil placement statute (302 F. 2d at 823):

8

The Pupil Assignment Law assigned, by legislative

enactment, all children who had previously been en

rolled in the schools to the same schools that they

had attended under the constitutional and statutory

separate racial system. They were to remain in these

same schools until graduation unless transferred by a

request of both parents. . . .

Any pupil through both parents may request a

transfer but in the final analysis it is up to the school

board to grant or reject it. Although an appeal may

be taken to the courts, it would be an expensive and

long drawn out procedure, with little freedom of action

on the part of the courts. In determining requests

for transfers, the board may apply the criteria here

tofore mentioned. None of these criteria is based on

race, but in the application of them, one or more could

always be found which could be applied to a Negro.

Then the court passed on the adequacy, both in theory

and practice, of the statute to end the biracial school sys

tem (302 F. 2d at 823) :

These transfer provisions do not make of this law a

vehicle to reorganize the schools on a non-racial basis.

Nor has the practice for four years under the law

been in the direction of establishing non-racial schools.

Negro children cannot be required to apply for that

to which they are entitled as a matter of right. If they

are deprived of their constitutional rights, they are

not required to seek redress from an administrative

body before applying to the courts. Borders v. Rippy,

247 F. 2d 268, C. A. 5. The burden rests with the

school authorities to initiate desegregation. Cooper

v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7, 78 S. Ct. 1401, 3 L. Ed. 2d

5. . . . As we have previously said, the Pupil Assign

9

ment Law cannot serve as a plan to organize the

schools as a non-racial system.

Of course, the exhaustion of remedies requirement was

held to be no impediment to the plaintiffs’ suit (302 F. 2d

at 823):

We do not discuss exhaustion of remedies under the

statute for the reason that we hold the Pupil Assign

ment Law is not adequate as a plan for reorganizing

the schools into a non-racial system.

The Fifth Circuit has consistently held that pupil place

ment statutes are no defense to class actions to desegregate

the public schools. Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction,

272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959); Mannings v. Board of Pub

lic Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370 (5tli Cir. 1960); Augustus v.

Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962);

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491 (5th

Cir. 1962); Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963).

Naturally, no individual plaintiff need exhaust adminis

trative remedies under these statutes. Armstrong v. Board

of Education of the City of Birmingham, 323 F. 2d 333

(5th Cir. 1963); Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District,------F. 2 d ------- (No. 20824, 5th Cir., Feb.

13, 1964), and cases cited.

In Bush, the Fifth Circuit said (308 F. 2d at 499) :

'This court, like both Judge Wright and Judge Ellis,

condemns the Pupil Placement Act when, with a fan

fare of trumpets, it is held as the instrument for carry

ing out a desegregation plan while all the time the

entire public knows that in fact it is being used to

maintain segregation by allowing a little token de

segregation. When the Act is appropriately applied,

10

to individuals as individuals, regardless of race, it

has no necessary relation to desegregation at all. . . .

The Act is not an adequate transitionary system in

keeping with the gradualism implicit in the “ deliberate

speed” concept. It is not a plan for desegregation at

all.3

CONCLUSION

Appellants’ submissions are simple and supported by

reason and authority: Racial segregation persists in the

Greene County public school system. Appellants seek in

this suit extirpation of the biracial school system. The

North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act is not designed to,

nor does it, provide for desegregation in accordance with

the mandate of the Supreme Court of the United States.

The provisions of the Act are, therefore, irrelevant to this

suit and compliance with them is not prerequisite to the

relief sought. Of course, the district court’s denial of in

junctive relief was error. On remand the district court

should be directed to provide for reorganization of the

schools on a unitary non-racial basis, and pending the

accomplishment of such reorganization, require the appel

3 The court cited Gibson, 272 F. 2d at 766:

[W ]e cannot agree with the district court that the Pupil

Assignment Law . . . met the requirements of a plan of

desegregation of the schools or contituted a “reasonable start

toward full compliance” with the Supreme Court’s May 17,

1954 ruling. That law and [implementing] resolutions do no

more than furnish the legal machinery under which com

pliance may be started and effectuated. Indeed, there is noth

ing in either the Pupil Assignment Law or the implementing

resolution clearly inconsistent with a continuing policy of com

pulsory racial segregation.

11

lee Board to permit plaintiffs and the members of their

class “ freedom of choice” in obtaining school assignments.

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621, 629 (4tli Cir. 1962).

Respectfully submitted,

Conrad (). P earson

203% E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Jack Greenberg

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

Norman C. A m a k er,

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

Of Counsel

J. L eV onne Chambers

38