Hopwood v. Texas Reply Brief for Proposed Intervenors-Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 15, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hopwood v. Texas Reply Brief for Proposed Intervenors-Appellants, 1995. 852f8e61-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c6c2e65b-eae8-48de-b4df-923aad214eb7/hopwood-v-texas-reply-brief-for-proposed-intervenors-appellants. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

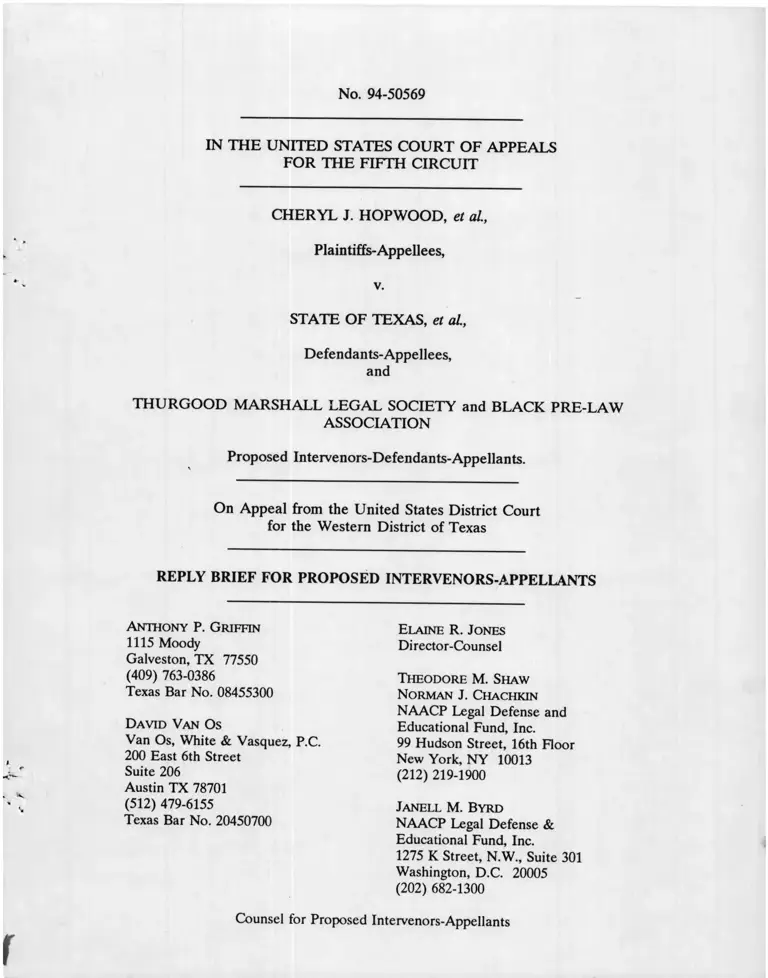

No. 94-50569

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

CHERYL J. HOPWOOD, et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

STATE OF TEXAS, et al,

Defendants-Appellees,

and

THURGOOD MARSHALL LEGAL SOCIETY and BLACK PRE-LAW

ASSOCIATION

Proposed Intervenors-Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Texas

REPLY BRIEF FOR PROPOSED INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

Anthony P. Griffin

1115 Moody

Galveston, TX 77550

(409) 763-0386

Texas Bar No. 08455300

David Van Os

Van Os, White & Vasquez, P.C.

200 East 6th Street

Suite 206

Austin TX 78701

(512) 479-6155

Texas Bar No. 20450700

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W., Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Counsel for Proposed Intervenors-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ..................................................................................................................i

ARGUMENT -

I Proposed Intervenor’s Claims Relating to the Validity

of the Texas Index Constitute an Important Alternative

Defense to Plaintiffs’ Challenge that the State of Texas

Refused to A sse rt.............................................................................................................1

II The Motion to Intervene Was Timely ...................................................................... 7

III Contrary to Clear Precedent, Plaintiffs Attempt to

Convert this Into a Rule 60(b) Motion Requiring Proof

of Extraordinary Circum stances...................................................................................11

IV TMLS and BPLA Have a Legally Protectible Interest in

the Outcome of this Case ............................................................................................ 14

V Permissive Intervention Should Have Been G ra n te d ............................................19

C onclusion...................................................................................................................................20

Certificate of Service..................................................................................................................21

Appendix A: Chronology

Table o f Authorities

Cases:

Aiken v. City o f Memphis, 37 F.3d 1155 (6th Cir. 1994) ......................................... 4, 5, 6

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975)......................................... „ 5

Billish v. City o f Chicago, 989 F.2d 890 (7th Cir.), cert,

denied,__ U .S .___ , 114 S. Ct. 290 (1 9 9 3 ).......................................................... 4, 5, 6

Ceres Gulf v. Cooper, 957 F.2d 1199 (5th Cir. 1992)..................................................... 7

Cleburne Living Center v. City o f Cleburne, 726 F.2d 191

(5th Cir. 1984) affd in part, vacated, 473 U.S. 432 (1 9 8 5 )......................................... 19

i

Pa^e

Cases (continued):

Cohn v. EEOC, 569 F.2d 909 (5th Cir. 1978) ............................................................... 18

Ensley Branch, NAACP v. Seibels, 31 F.3d 1548 (11th Cir.

1994)........................................................................................................................... 4, 5, 6

EPA v. Green Forest, 921 F.2d 1394 (8th Cir. 1990), cert,

denied sub nom. Work v. Tyson Foods, 112 S. Ct. 414 (1991) ................................ 12

Florida General Contractors v. Jacksonville, 508 U .S .___,

124 L. Ed. 2d 586 (1993) .............................................................................................. 16

Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363 (1982)................................................... 18

Hines v. Rapides Parish School Board, 479 F.2d 762 (5th Cir.

1973).................................................................................................................................. 18

Hodgson v. United Mine Workers of America, 473 F.2d 118

(D.C. Cir. 1972)............................................................................................................... 13

Hopwood v. State o f Texas, 861 F. Supp. 551 (W.D. Tex.

1994)..................................................... ...................................................................... 2 ,11 ,17

Hopwood v. Texas, 21 F.3d 603 (5th Cir. 1994) .......................................................... 9, 19

Howard v. McLucas, 782 F.2d 956 (11th Cir. 1986) ..................................................... 18

Hunt v. Washington State Apple Advertising Comm’n,

432 U.S. 333 (1 9 7 6 ) ................................................................................................... 18-19

In re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination Litigation, 833 F.2d

1492 (11th Cir. 1 9 8 7 )...................................................................................................... 18

Knight v. Alabama, 14 F.3d 1534, 1540 (11th Cir. 1994).............................................. 17

Meek v. Metropolitan Dade County, Fla., 985 F.2d 1471

(11th Cir. 1 993 )........................................................................................................ 12, 13

New York Public Interest Research Group, Inc. v. Regents of

University of New York, 516 F.2d 350 (2d Cir. 1975) ................................................. 18

Pasadena City Board o f Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S.

424 (1976).................................................................................................................... i . 19

Table of Authorities (continued)

ii

Page

Cases (continued):

Sierra Club v. Espy, 18 F.3d 1202 (5th Cir. 1994).......................................................... 8

Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558 F.2d 257 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 7 )....................................... passim

United States & Ayers v. Fordice, 505 U .S .___,

120 L. Ed. 2d 575 (592) ................................................................................................. 17

United States v. Fordice, 112 S. Ct. 2727 (1 9 9 2 )............................................................ 17

United States v. Perry County Board o f Education,

567 F.2d 277 (5th Cir. 1978)............................................................................................ 18

Statutes and Rules:

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(l) .......................................................................................................... 6

Fed. R. Civ. P. 2 4 .................................................................................................................... 7

Fed. R. Civ. P. 6 0 (b )............................................................................................................. 11

Other Authorities:

Charles A. Wright, Arthur R. Miller & Mary K. Kane,

Federal Practice and Procedure (1986) ............................................................................. 18

Table o f Authorities (continued)

iii

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

The Thurgood Marshall Legal Society ("TMLS") and the Black Pre-Law Association

("BPLA"), organizations composed primarily of African-American students - many of

whom are current and potential beneficiaries of the affirmative action admissions program

at the University of Texas Law School ("Law School’) — filed a new motion to intervene

in this action after it became unequivocally clear at trial that the State defendants would

not adequately represent their interests (R. 1451-57). This appeal is taken from the denial

of their motion.

Plaintiffs-Appellees’ Opposition Brief ("Op. Br.") launches a scattershot attack on

the motion, challenging virtually every assertion contained in our opening brief, no matter

how tangential to the central issues presented to this Court. We cannot respond to every

charge and implication raised by plaintiffs within the page limitations of a reply;

accordingly, we limit this brief to the key points with which the Court must deal.

ARGUMENT

I. Proposed Intervenors’ Claims Relating to the Validity of the Texas Index Constitute

an Important Alternative Defense to Plaintiffs’ Challenge that the State of Texas

Refused to Assert._____________________________________________

TMLS and BPLA fully agree with the grounds asserted at trial by the State of Texas

in defense of the Law School’s affirmative action admissions program and urge this Court

to affirm the judgment below on the merits appeal. However, these proposed intervenors

also pursue this appeal in order fully to protect their interests, especially in the event that

the Court holds that the defense asserted at trial by the State is not sufficient to defeat

plaintiffs’ claims. In that event, it is essential that TMLS and BPLA be permitted to

participate in any further proceedings in this action since the inadequacy of the State’s

representation of their interests is now clear.

There is, of course, no dispute that the State failed to rebut the assertion that the

Texas Index ("TI") was equally valid for both Anglo and African-American students, and

therefore failed to pursue this alternative defense to plaintiffs’ complaints and the relief

they requested. The theory upon which plaintiffs relied at trial to establish a constitutional

violation, and to support their demand to be admitted to the law school, was grounded

explicitly upon the claimed validity of the TI for all applicants. Plaintiffs’ expert, Dr. David

Armor, testified that the use of different cut scores by race was "critical" to his conclusion

that the admissions program discriminated against white applicants: "[W]hen — by virtue of

your race you can get in, you have a very high probability of getting in with a much lower

score, I think that is a discriminatory system . . ." (Tr. Vol. 11, p. 46). Dr. Armor’s

testimony centered around a key piece of plaintiffs’ evidence, a chart "that depicts the TI’s

of all 1992 applicants and whether they were offered or denied admission. P-139 . . . . The

chart emphasizes the disparity in TIs between resident minority and nonminority applicants

. . . ," Hopwood v. State o f Texas, 861 F. Supp. 551, 580 (W.D. Tex. 1994).1 Dr. Armor

opined that the TI "has been proven to be a valid predictor of success in law school" (Tr.

Vol. 10, p. 30), and that "the LSAT plus the grade point average is a very good predictor

of first year law school performance or grades in law school" {id.).

TMLS and BPLA sought to intervene for the purpose of contesting the validity and

legality of using the TI, without an affirmative action adjustment, as an admissions device

at the Law School (R. 1451-57). They had repeatedly attempted, both before and during

the trial, to convince the State to raise the TI’s invalidity for African-American students as

an alternative defense to plaintiffs’ claims. But, although State defendants were well aware

of the results to be anticipated from sole reliance upon the TI as a selection criterion,2 and

although they had information revealing the relationship between TI scores and first-year

performance of students admitted to the Law School (PX-136, -137), they presented

‘The district court explicitly found that the chart "does not prove, however, that race

or ethnic origin was the reason behind the denial of admission. . . . [T]he evidence shows

that 109 nonminority residents with TIs lower than Hopwood’s were offered admission.

Sixty-seven nonminority residents with TIs lower than the other three plaintiffs were

admitted." 861 F. Supp. at 581 (footnotes omitted).

2"[W]ithout affirmative action, the Law School’s 1992 entering class of 514 students

would have included at most only 9 blacks (1.8%) . . . ," Brief of Appellees in Hopwood v.

Texas, No. 94-50664 (5th Cir., filed February 10, 1995), at 5.

2

testimony supporting the TI as a fair and valid predictor of success at the Law School

regardless of race or ethnicity (Tr. Vol. 3, p. 11). This "tactical decision" served the Law

School’s interest in minimizing the possibility that it would be required to find or develop

a substitute for an admissions criterion that works well for the vast majority of the students

— Anglos — whom it enrolls, but it substantially disserved the interests of African-American

students and potential applicants to the Law School. The State’s position substantially

increased the risk that the outcome of this litigation would be a directive to use the same

TI cut scores for all applicants since the State conceded its validity for all races.3 In other

words, the State defendants allowed their interest in administrative convenience to prevail

over African-American students’ interest in a fair and nondiscriminatory admissions

process.

Plaintiffs seek to sweep under the rug this failure of the State defendants to

represent the interests of the proposed intervenors by attacking the substantive merits of

the claims intervenors sought to raise about the TI.4 Their arguments, however, rest upon

a misreading of the decisions upon which they seek to rely and indicate the need for

adequate factual and legal development of these issues in the district court before this

Court may appropriately resolve them. Such development can only occur, of course, if

3Plaintiffs now contend that they do not "advocate sole, or even significant, reliance on

‘numbers’ (i.e. Texas Index scores)," Op. Br. at 37 (quoting post-trial brief), but urge this

Court to render a judgment that would result in the entry of an injunction prohibiting any

consideration of race in admissions and "requiring a single standard applicable to all races,"

id. Not only is this disclaimer inconsistent with a key focus of plaintiffs’ liability theory at

trial — which was a comparison of the TI scores of white and African-American applicants

who were granted or refused admission - but it also blinks the reality that, because of the

State’s refusal to present the evidence offered by proposed intervenors, on this record the

only "single standard" upon which admission could be based is the TI, which the parties

agreed was valid for all groups.

“For example, plaintiffs criticize (Op. Br. at 22) the sample size of one of the studies

utilized by proposed intervenors’ expert witness, Dr. Martin Shapiro, see Shapiro

Declaration, Appellants’ Record Excerpts ("App. R.E."), Tab C. They fail to note that the

studies were placed in evidence by the plaintiffs themselves (PX-136, -137), for the purpose

of establishing the validity of the TI.

3

TMLS and BPLA are permitted to intervene if there are any further proceedings in this

matter.

Relying upon a series of employment cases, all involving consent decrees,5 plaintiffs

assert that proposed intervenors raise "no[] defense at all" because a public agency may not

justify race-conscious affirmative action on the ground that its selection device is racially

discriminatory. Op. Br. at 23-25. The situations in each of these cases, however, are very

different from the record before this Court.

In each of the employment cases, Title VII plaintiffs had challenged hiring or

promotion decisions based on tests that had a racially discriminatory impact (i.e., that

disqualified minority applicants at much higher rates than whites) and had never been

validated (i.e., had not been shown to measure skills or qualities necessary to perform

successfully the jobs for which they were being used). In particular, there had been no

showing that the tests had predictive validity for any employees, white or minority, in the

sense that high ranking on the tests had been shown to correlate well with good job

performance by incumbents. In each case, the municipal defendants in those Title VII

actions had settled the cases, promising to develop "validated" selection criteria.6 Until

those new procedures could be developed, the decrees — approved by the courts — provided

that race-conscious adjustments could be made to mitigate the discriminatory impact of the

unvalidated examinations.

Despite the language of the decrees, none of the municipalities devised new and

validated selection methods; instead, for periods ranging from eight to fifteen years, some

hiring or promotions continued to be made on an explicitly racial basis, justified by

5Aiken v. City o f Memphis, 37 F.3d 1155 (6th Cir. 1994)(en banc)\ Ensley Branch,

NAACP v. Seibels, 31 F.3d 1548 (11th Cir. 1994); Billish v. City o f Chicago, 989 F.2d 890

(7th Cir.) (en banc), cert, denied,__ U .S .___ , 114 S. Ct. 290 (1993).

6See Aiken, 37 F.3d at 1164; Ensley, 31 F.3d at 1571-72; Billish, 989 F.2d at 894.

4

reference to the original, non-validated tests.7 The three cases upon which plaintiffs rely

were brought to challenge this continued use of explicitly racial criteria for decisionmaking.

In each, the Courts of Appeals expressed great concern at the municipalities’ failure to

devise job-valid procedures that might eliminate the need for race-consciousness. But none

of the cases announced the sort of sweeping rule described by plaintiffs (Op. Br. at 23).

Instead, each case was remanded to the district courts to determine whether there were,

in fact, alternatives to race-based decisionmaking.8

In the present case, the Law School’s preferred selection device (the TI) appears to

have some predictive validity for the majority of its students - Anglos — as proposed

intervenors’ expert Dr. Shapiro found through a differential validation analysis, see

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 435 (1975). However, the TI appears

to have virtually no validity at all for African Americans, see Shapiro Declaration, App.

R.E., Tab C, at 16-17. TMLS and BPLA contend that by lowering the cut scores for

African Americans, the Law School therefore was not discriminating against whites but was

avoiding discrimination against African Americans by neutralizing the discriminatory impact

of a selection mechanism which, as to them, had no validity. The three cases upon which

plaintiffs rely are inapposite, since in each one what was involved was a non-validated test

1See, e.g., Ensley, 31 F.3d at 1575 ("Until valid job-selection procedures are in place,

some use of racial preferences is necessary to counteract the ongoing effect of racially

discriminatory testing").

8Indeed, the Courts of Appeals took pains to avoid announcing any rigid rules. In

Billish, for example, the dicta quoted by plaintiffs, Op. Br. at 23, concerning the invalidity

of "bootstrapping" a justification for race-conscious decisionmaking by continuing to utilize

a biased test, follows the Court’s holding that a public entity should avoid the use of racial

criteria "whenever it is possible to do so," 989 F.2d at 894. Similarly, in Ensley, 31 F.3d at

1575, the Court noted that "even after valid selection procedures are in place, affirmative

action may be needed to cure past discrimination by the City and the Board." Finally, in

Aiken, the district court was instructed on remand to consider whether the race-conscious

remedy could still be considered "narrowly tailored" in light of "the City’s failure to utilize

or even develop validated procedures for promotions in the police and fire departments"

37 F.3d at 1167.

5

rather than a measure with predictive validity for one group and little or no validity for

another.9

Because neither the plaintiffs nor the defendants contested, but rather each affirmed,

the validity of the TI for African Americans, the question whether there are available some

other selection standards having equal validity for Anglos and minority students was never

raised.10 (Indeed, as noted above, plaintiffs’ case was bottomed upon the assumption that

the TI was equally valid for minority and non-minority applicants.11) It may be that other

selection criteria that meet the Law School’s desire to admit students who can perform

successfully in their first year may also have differential validity across racial and ethnic

groups.12 If that is the case, differential application of those criteria, as in the case of the

TI, would be justified by "business necessity" and would not constitute discrimination

against plaintiffs or any other members of a particular racial or ethnic group. The one

thing that is certain is that the question was neither raised nor tried before the district

court and, therefore, this defense to the Law School’s practices cannot be rejected by this

9Plaintiffs also cite (Op. Br. 25) 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(l), which makes illegal the

adjustment of scores according to race on "employment related tests." The quoted phrase

is entirely consistent with the holdings in the cases discussed above, which recognize the

legitimacy of race-conscious action to avoid any discriminatory impact from tests that are

not validated as job-related. Apart from the fact that no such provision applies to

Fourteenth Amendment or Title VI claims, the TI is "unrelated" in a classic sense for

African Americans, for whom the instrument has no validity for predicting success at the

Law School.

10Selection by lottery, suggested in passing by plaintiffs (Op. Br. at 36), would hardly

seem to be capable of validation as manifestly related to the goal of admitting students

likely to succeed during the first year.

"To the extent that plaintiffs had sought to prove this assumption at the trial below,

in order to try to move this case closer to Aiken, Ensley and Billish, this merely emphasizes

the importance, to the protection of proposed intervenors’ interests, of contesting the

assumption -- which the State defendants consciously chose not to do.

12The Office for Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Health, Education & Welfare

recognized this in 1975 when it informed Texas of the need to validate its admission criteria

by program and by race (R. 1253).

6

Court without an adequate record before it. Only the proposed intervenors seek to make

that record, but they must be admitted to the case as parties in order to do so.

II. The Motion to Intervene Was Timely.

By focusing sharply on the issue of timeliness of the first motion to intervene filed

by TMLS and BPLA,13 plaintiffs’ opposition brief gives little attention to the question at

issue on the instant appeal — whether the second motion was timely filed. Because the time

frame and the scope of the two requests for intervention are wholly different, and because

they rest upon different showings with respect to when movants knew and could

demonstrate that the State’s representation of their interests would be inadequate,

plaintiffs’ argument serves more to confuse than to elucidate the issue.

The factors established by this Court for guiding determinations of timeliness under

Fed. R. Civ. P. 2414 are:

1. The length of time during which the would-be intervenor actually knew or

reasonably should have known of his interest in the case before he petitioned

to intervene . . . 2. The extent of the prejudice that the existing parties to the

litigation may suffer as a result of the would-be intervenor’s failure to apply

for intervention as soon as he actually knew or reasonably should have known

of his interest in the case . . . 3. The extent of prejudice that the would-be

intervenor may suffer if his petition for leave to intervene is denied . . . [and]

4. The existence of unusual circumstances militating either for or against a

determination that the application is timely.

13Neither the district court, nor this Court in its affirmance of the denial of the first

motion to intervene, ruled that the motion was untimely (R. 742-46, 1240-47). The district

court’s discussion of potential "delay," in its ruling denying the first motion for intervention,

is substantively and legally distinct from a finding that the motion was untimely under the

standards set by this Court. See text infra. Plaintiffs’ attempt to construe this language in

the district court’s first order denying intervention as a timeliness determination relevant

to the motion to intervene as of right (Op. Br. at 4) is most inappropriate, especially in

view of the fact that the court’s discussion of delay came in the portion of its order

discussing the request for permissive intervention (R. 746).

14Plaintiffs’ assertion that the timeliness issue should be reviewed only for abuse of

discretion, Op. Br. at 40 n.14, is wrong. See Ceres Gulf v. Cooper, 957 F.2d 1199, 1202 n.8

& accompanying text (5th Cir. 1992) (where district court does not indicate timeliness as

reason for denial of intervention the standard of review on each of the factors is de novo).

7

Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558 F.2d 257, 263-66 (5th Cir. 1977); see also Sierra Club v.

Espy, 18 F.3d 1202 (5th Cir. 1994). The relevant inquiry on the first factor is the timeliness

of the application for intervention at the time it was made in relation to the point at which

the proposed intervenor "became aware that her interest ‘would no longer be protected by

the named representative,’" Stallworth, 558 F.2d at 264 (internal citations omitted).15

First, proposed intervenors filed their renewed motion to intervene in a timely

manner - less than three weeks after the district court ruled that the evidence on the

validity of the Texas Index would not be considered. Plaintiffs contend that proposed

intervenors’s motion is untimely because its was not filed prior to trial.16 However, that

is absurd. The appeal on the denial of the first motion to intervene was pending in this

Court until five days prior to trial (R. 1240). In affirming, this Court ruled that there was

not a sufficient demonstration that the State defendants would not adequately represent

the interests of TMLS and BPLA. After that ruling, no fact changed until defendants

rested their case without rebutting the validity of the Texas Index as applied to African

Americans.17 This changed circumstance demonstrated the inadequacy of the State’s

representation of proposed intervenors’ interests. A new motion to intervene coming on

15Because plaintiffs misleadingly omit key dates in their discussion, a chronology of

relevant events is set out in Appendix A to this brief. It demonstrates that TMLS and

BPLA made a consistent and timely effort to participate in this action, from the time that

the potential inadequacy of the State’s representation first appeared through the time that

its actuality was demonstrated at trial.

16Op. Br. at 14 ("student groups should have made their renewed motion prior to trial"),

id. at 27 ("they should have made their second motion long before the trial") (emphasis in

original), id. at 28 ("[hjaving failed to make the second motion before trial, the students

groups have created a situation where nothing but prejudice to the parties can result")

(emphasis in original).

17During trial proposed intervenors offered Dr. Shapiro to State defendants to rebut

evidence regarding the validity of the TI, but defendants rejected the offer, maintaining the

position that they would not challenge the TI.

8

the heels of this Court’s affirmance would have done nothing more than possibly provide

a basis for sanctions against proposed intervenors.

At that point, when defendants rested, the trial court announced that TMLS and

BPLA would be allowed to put their evidence in the record.18 A motion at the close of

trial therefore would have been unnecessary; the relief movants sought was then available.

It was not until the trial judge ruled that the evidence regarding the Texas Index would not

be considered that the inadequacy of the representation became demonstrable and

palpable. (We note, however, that the renewed motion was not made necessary by any

failure on the part of proposed intervenors to seek to demonstrate, at the time of their

initial attempt to enter the case, that the State would not challenge the validity of the TI.19)

18"I am already committed to at least ten days to intervenors who have been very patient

sitting there. They will be able to produce whatever they would like in the record," Tr. Vol.

25, at 11-12 [emphasis added]. On May 25, 1994, the Court added: "For the intervenors

which I have permitted, they will have the same time. I will not make any limitations. The

intervenors will not be barred or limited by the local rules on pleadings in this particular

case," Tr. Vol. 27, at 48-49. From these statements, TMLS and BPLA understood that the

Court was inviting their participation and that their evidence would be allowed in the

record, thereby obviating the need to renew their motion to intervene.

19TMLS and BPLA requested a hearing on their initial motion (Letter of January 5,

1994 from Anthony Griffin to Deputy Clerk Robert J. Williams, submitted with Motion to

Intervene) but the district court denied intervention without a hearing; thus, there was no

opportunity to make an evidentiary record. They asserted on appeal from that denial of

intervention that the State would fail to challenge the TI, but this Court concluded that

proposed intervenors had not "shown that they have a separate defense of the affirmative

action plan that the State has filed to assert," Hopwood v. Texas, 21 F.3d 603, 606 (5th Cir.

1994) (emphasis added). The Court added that it expected proposed intervenors to provide

their evidence to the State, which would present it (id. at 605-06):

Although BPLA and TMLS may have ready access to more evidence than the

State, we see no reason they cannot provide this evidence to the State. The

BPLA and the TMLS have been authorized to act as amicus and we see no

indication that the State would not welcome their assistance.

Only after the trial was completed was it undeniable that the State had failed to assert this

important defense against plaintiffs’ charge of racial discrimination.

9

Second, plaintiffs’ assertion of prejudice from the timing of the filing of the motion

to intervene is also without merit. "[T]he relevant issue is not how much prejudice would

result from allowing intervention, but rather how much prejudice would result from the

would-be-intervenor’s failure to request intervention as soon as he knew or should have

known of his interest in this case," Stallworth, 558 F.2d at 267 (emphasis added). There was

no delay of any significance in filing the second motion to intervene in this case. Less than

three weeks passed between the district court’s order stating that it would not consider Dr.

Shapiro’s declaration and the date of filing. Nothing happened during that period that

would have caused plaintiffs any prejudice from a grant of intervention on the 12th of July,

when the motion was filed, that would not also have existed on the 22nd of June, when the

district court ruled that it would not consider the evidence, or on May 25th when the trial

ended. The district court did not issue its opinion until August 19, 1994.

Moreover, plaintiffs were aware prior to trial that, if they were granted intervention,

TMLS and BPLA planned to challenge the validity of the TI for African-American

students. Even though that intervention was denied, plaintiffs themselves sought to prove

the validity of the TI in their case in chief, through the testimony of Dr. Armor and their

exhibits PX-136 and -137. Plaintiffs would therefore have suffered no more prejudice had

the district court allowed proposed intervenors to rebut that presentation than they would

have experienced if the State had sought to counter their showing20

The third factor that the Court considers in determining timeliness — prejudice to

the movants in the event intervention is denied - weighs in favor of TMLS and BPLA.

If this Court reverses the district court’s ruling insofar as it allows the State to continue to

consider race as a factor in admissions and directs the district court to grant the injunctive

relief sought by plaintiffs, the ability of any African American to require the State to

reinstitute the consideration of race, as a practical and legal matter, will be virtually nil.

“ In fact, depositions of rebuttal witnesses occurred during the middle of the trial. On

May 22, 1994, plaintiffs took the deposition of defendants’ witness Mr. De La Garza.

10

While plaintiffs dance delicately around the issue and suggest that the number of African

Americans at the Law School may not diminish if affirmative action in admissions is

eliminated (Op. Br. at 35), the trial record unmistakably establishes the likelihood that the

African American presence at the Law School will diminish precipitously, as the district

court found, 861 F. Supp. at 571. Even an admissions program that considers

"disadvantage" — which arguably is race neutral — will likely be insufficient without race as

an independent factor. Plaintiffs’ expert witness conceded at trial that the history of

discrimination in education means that race itself is a significant disadvantage for African

Americans.21 Allowing plaintiffs to seek to show discrimination against them by the Law

School based primarily on the use of the TI in the admissions process, without

consideration of the critical fact that the TI is not a valid predictor of performance at the

Law School for African Americans, prejudiced movants in a most serious and substantial

manner.22

Consideration of all of the factors strongly supports a conclusion that the motion to

intervene was timely.

III. Contrary to Clear Precedent, Plaintiffs Attempt to Convert this Into a Rule 60(b)

Motion Requiring Proof of Extraordinary Circumstances.______________________

Plaintiffs suggest that proposed intervenors were required to establish "extraordinary

circumstances" in order to obtain the relief sought in their second motion, Op. Br. at 15-17,

because, they say, the second TMLS and BPLA motion to intervene was a motion for

reconsideration that should have been brought under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b). However, the

21Dr. Armor testified that socioeconomic characteristics of students’ parents, including

parental education level, are the strongest correlates of both black and white achievement

levels. He admitted that to the extent that there was a constriction of opportunity for the

first generation [parents], one would expect that "constriction of opportunity to be

manifested in the socioeconomic status of generation 2 [children]," thereby affecting

negatively the educational attainment of the children (Tr. Vol. 11, pp. 28-29).

22See Appellants’ Opening Brief at 25 for a discussion of the fourth Stallworth factor,

which militates in favor of proposed intervenors.

11

motion at issue did not seek "reconsideration" of the original ruling denying intervention;

rather, it sought intervention for the limited purpose of presenting evidence of a defense

that the State defendants failed to raise, and without which the trial court’s analysis of the

issues presented might have been fundamentally impaired (to the detriment of proposed

intervenors).

Plaintiffs urge this Court to ignore the rulings of all of the other federal Courts of

Appeal that have considered this issue, which have held that successor petitions for

intervention appropriately can be considered by district courts, in their discretion, when the

circumstances have changed after disposition of an earlier motion. In EPA v. Green Forest,

921 F.2d 1394, 1401 (8th Cir. 1990), cert, denied sub nom. Work v. Tyson Foods, 112 S. Ct.

414 (1991), for example, the Eighth Circuit ruled that a second motion to intervene brought

in a context "different from the context in which intervention . . . had been sought [earlier]"

could be granted where developments in the case "resulted in a change in circumstances

that made a renewed motion for intervention legitimate." In that case, the movants had

expressed concern some sixteen months earlier (in their first motion to intervene) about

harm from a possible settlement, but the settlement possibility then was merely "inchoate."

Id. "In their second motion, the citizens made specific reference to the proposed settlement

and articulated their specific objections to the consent decree . . . ." Id. Thus the existence

of the consent decree constituted the change in circumstances that warranted the court’s

consideration and approval of the renewed motion to intervene. See id. at 1401-02.

Similarly, in Meek v. Metropolitan Dade County, 985 F.2d 1471, 1475 (11th Cir. 1993),

two registered voters were initially denied intervention because the court determined that

their interests were "identical" to those of the existing official defendants who could be

relied upon to represent the voters adequately. Prior to trial, the voters unsuccessfully

renewed their motion to intervene, explicitly seeking to preserve the ability to take an

appeal. Following a three-week trial, the district court ruled against the defendant county,

which subsequently decided not to appeal. The voters again renewed their motion to

12

intervene for the purpose of taking an appeal, id. at 1476. The Court ruled that the

county’s "decision to forego its right to appeal the district court’s injunction was a sufficient

change in circumstances to justify a renewed motion for intervention . . . Id. at 1477.

In Hodgson v. United Mine Workers o f America, 473 F.2d 118, 125 (D.C. Cir. 1972),

the Court ruled that district courts are required to "exercise a considerable degree of

discretion" on applications for intervention, and that the "various factors which guide the

exercise of discretion may change substantially as the litigation progresses":

Where, as here, a court’s ruling has discretionary elements based on

circumstances which are subject to alteration, the law recognizes the power

and responsibility of the court to reconsider its ruling if a material change in

circumstances occurred.

Id. The panel held that courts routinely consider renewed motions for summary judgment,

for example, where additional facts become available, or proof of such facts becomes

uncontrovertible. Id. at 126 & n.38. The court concluded that the changed circumstances

in the four months between the first and second applications for intervention "required"

consideration of the second motion to intervene, independent of the first. Id. at 126. The

most important new circumstance justifying the court’s consideration of the second motion

to intervene was the fact that the district court had entered an opinion holding certain

actions illegal and requesting the defendant to file a proposed remedial decree. This added

"new urgency and weight" to the application for intervention because it bore out the

proposed intervenors’ claim and without intervention they would have no voice in

fashioning the relief. Id. at 126. The Court approved the post-trial motion to intervene.

These cases establish that changed circumstances, such as those occurring here,

warrant the court’s consideration of the second request to intervene without a showing of

"extraordinary circumstances" under Rule 60.23

23Plaintiffs argue that the denial of the first motion was "final" because it was upheld

on appeal, and for this reason it should weigh heavily in favor of requiring a showing of

"extraordinary circumstances" on any successor motion (Op. Br. at 17). However, this

Court’s jurisprudence establishes that where the Court of Appeals concludes that the denial

13

IV. TMLS and BPLA Have a Legally Protectible Interest in the Outcome of this

Case._____________________________________________________________

Plaintiffs challenge proposed intervenors’ assertion that they have a legally

protectible interest in the outcome of this matter, both as organizations and on behalf of

their members. Specifically, plaintiffs argue that (1) the organizations have no legally

protectible interests as organizations because they have asserted only "broad organizational

goals" for which the law provides no protection; (2) that the organizations have not

identified by name their members whose interests will be impaired, and some of the

persons who were members of the organizations at the time the motion for intervention was

filed have now graduated; and (3) that the interests of proposed intervenors are "irrelevant

and speculative" because, according to plaintiffs, there is no policy traceable to the de jure

system at issue in this case and it is wholly speculative whether the relief requested by

plaintiffs - a bar on any consideration of "race or sex" (Op. Br. at 37) in admissions -

would result in,fewer African Americans at the Law School. As demonstrated below,

movants have direct, substantial and legally protectible interests in this litigation

notwithstanding plaintiffs’ strained arguments to the contrary.

Plaintiffs’ opening brief on the merits sets out the primary goal of this litigation,

which is to enjoin permanently any consideration of race by the Law School in admissions.

Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants Hopwood and Carvell, No. 94-50664 (5th Cir. filed December

19, 1994), at 49. As stated in proposed intervenors’ opening brief (at 26):

th[is] result would impede proposed intervenors’ constitutional and statutory

interest in remedying the harm caused by the State defendants’ pattern of

intentional discrimination against African-American students, as found by the

district court.

The consideration of race in admissions serves as a remedy for the State’s racially

dual system in several ways. As outright exclusion of African Americans from the public

of intervention was correct, appellate jurisdiction "evaporates because the proper denial of

leave to intervene is not a final decision . . . ." Stallworth, 558 F.2d at 263.

14

schools of Texas designated for whites, including the Law School, was the hallmark of the

racially dual system, the racial focus of the violation meant that the injury had a distinctly

racial character. The consideration of race in admissions recognizes this harm and attracts

and matriculates more African-American students, thereby creating a less isolating

experience for black law students and aiding long-term recruitment, retention and

graduation. The policy helps to remedy the dearth of African-American attorneys caused

by past discrimination, and by attracting and admitting meaningful numbers of high-

achieving African Americans, the policy helps to eliminate the stigmatic message of

inferiority and exclusion that are part and parcel of segregated systems. The admissions

program also increases ethnic and ideological diversity on campus, to the benefit of all

students. The ability to consider the key factor of race is critical to the Law School’s

efforts to achieve these goals. Each of these goals directly implicates the interests of the

proposed intervenor organizations and their members.

BPLA’s central organizational objective is to increase the number of African

American legal scholars entering the University of Texas and other law schools.24 The

Declaration of the BPLA’s president, Suneese Haywood (R. 761),25 emphasizes the

following:

10. BPLA seeks to aid African-American students in applying to the Law

School [University of Texas]. In 1993 BPLA arranged for members of the

Thurgood Marshal Legal Society (an organization of African American

students at the Law School) to speak to BPLA members about the Law

School’s admissions process and the study of Law at the University of Texas.

12. Because many of BPLA’s members seek admission to the University of

Texas School of Law, the Law School’s affirmative action admission policy

is vital to BPLA’s goals and the interest of our members.

^BPLA Constitution, Art. I, II, Exhibit 1 to Exhibit B of Proposed Intervenors’

Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene (R. 674); see also (R. 760-68).

“ The documents filed in support of the first motion to intervene, which, inter alia,

identified the proposed intervenors, were incorporated by reference in the renewed motion

to intervene (R. 1451-52).

15

Beyond BPLA’s organizational goals, the members of BPLA are primarily African

American undergraduates, many of whom will apply and be considered under the Law

School’s admission policy. BPLA members, therefore, have a direct interest in a program

that will aid their admission to law school. Cf Florida Gen. Contractors v. Jacksonville, 508

U .S .___, 124 L.Ed. 2d 586, 599 (1993) (where organization’s members regularly bid on

defendant’s public contracts, organization has standing to challenge impediments to

successful bid). The Law School’s positive consideration of race in the admissions process

is designed primarily to correct the former policy of whites-only admissions and the State’s

channelling of students by race to law schools under the dual structure which continues to

exist with the Thurgood Marshall Law School, (known as "the house that Sweatt built"),

being the institution primarily designated by the State for the legal education of African

Americans.26 BPLA members have an interest in being considered under a policy

designed to counter the illegal segregated structure that continues to operate.

TMLS’s key organizational goals include encouraging a racially mixed student body

and eliminating racial discrimination at the Law School.27 The Declaration of April

Cheatham, the President of TMLS and a former BPLA member (R. 769-71), states as

follows:

8. TMLS’fs] central goals are to encourage the admission, retention, and

academic success of greater numbers of African-American scholars at the

Law School; to promote an academic and social atmosphere that is both

attractive and receptive to students of color; and to combat discrimination

and its effects on the Law School campus and elsewhere.128'

“ Plaintiffs admit the existence of this school is a vestige of the racially dual system (R.

1401, Par. 56).

27TMLS Constitution, Art. 1, Section B, Exhibit 1 to Exhibit A of proposed intervenors

Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervenor (R. 659), see also (R. 769-82).

“ Plaintiffs argued that no TMLS members have an interest, distinct from those of the

organization, because any change in the number of black students admitted would take

place over several years. Therefore, they reason, persons who were TMLS members in July

of 1994, when the motion to intervene was filed, will have graduated and will not be

16

9. In order to help attract African-American students to the Law School,

TMLS’s members act as a source of information for African-American

prospective law students, answering their questions about the Law School and

encouraging their attendance.

17. All of TMLS’s members are students at the Law School and each of

them is directly affected by the racial atmosphere on campus, the school’s

reputation for discrimination, and other effects of the Law School’s past

discrimination. Elimination of the existing admissions policy would drastically

increase these negative effects.

TMLS, BPLA and their members have a direct, substantial and legally protectible

interest in a desegregated law school where they are assured that the State "has met its

affirmative duty to dismantle its prior dual university system." United States & Ayers v.

Fordice, 505 U .S .___, 120 L.Ed.2d 575, 592 (592); see also id. at 590 (recognizing role of

private plaintiffs); Knight v. Alabama, 14 F.3d 1534, 1540 (11th Cir. 1994) (same).

Plaintiffs concede that some African American students "might" have an interest

under United States v. Fordice, 112 S. Ct. 2727 (1992), in attending a university that has

dismantled its racially dual system, Op. Br. at 33. They assert, incredibly, that that "interest

has nothing to do with this lawsuit." Id. Indeed, it was plaintiffs’ theory of the case that

the history of discrimination by the State essentially evaporated without a trace. The

district court expressly considered the legal duty imposed by Fordice, 861 F. Supp. at 571,

and rejected plaintiffs’ theory. "Accordingly, despite the plaintiffs [s/c] protestations to the

contrary, the record provides strong evidence of some present effects at the law school of

past discrimination in both the University of Texas system and the Texas educational system

as a whole." Id. at 573. * *

affected by the time the change occurs. Op. Br. at 33, n.12. The record of admissions at

that Law School demonstrates that the number of black law students can drop and has

dropped dramatically in the course of one year. 861 F. Supp. at 574, n.67. Furthermore,

the organization gains new members each year whose rights and interests TMLS seeks to

protect in a representational capacity.

17

Comm’n, 432 U.S. 333, 342-45 (1976), the Court recognized the standing of the State Apple

Advertising Commission in a representative capacity to protect the interests of the State’s

apple growers. In this case, BPLA and TMLS have a substantial and protectible legal

interest both in their own right, in defending their organizational goals, and on behalf of

their members who share the goals of the organizations and who are the beneficiaries of

the Law School’s affirmative action policy.

Plaintiffs further criticize proposed intervenors for allegedly failing to comply with

Cleburne Living Center v. City o f Cleburne, 726 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1984), tiff'd in part, vacated

in part, 473 U.S. 432 (1985), which plaintiffs assert requires the organizations to name their

individual members who are likely to be affected. Plaintiffs complain that "the student

groups have never bothered to identify anyone (much less a member) whose interests are

at stake." Op. Br. at 31. Apart from whether plaintiffs have correctly interpreted that

opinion, their argument can be put to rest by noting simply that movants submitted two

declarations in support of their motion, that of Suneese Haywood and April Cheatham.

(R. 760-782). Suneese Haywood is currently a member of BPLA with an application for

admission pending at the Law School.30 The declarations name other members of TMLS

and BPLA who were officers and persons with a direct interest in this litigation.

V. Permissive Intervention Should Have Been Granted.

Plaintiffs argue that because permissive intervention was properly denied with

respect to the first motion, because the district court found movants were adequately

represented and that intervention would cause delay, see 21 F.3d at 606, denial of the

second motion for permissive intervention was necessarily proper. Op. Br. at 41.31 At the

30Plaintiffs’ suggestion that because some of the organizations’ members will have

graduated that none of the members have a legally protectible interest is equally without

merit. As long as there is one party with standing to bring an action the case remains

justiciable. See Pasadena City Bd. o f Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 430-31 (1976).

31Plaintiffs’ jurisdictional argument (Op. Br. at 1) fails to understand the essence of the

Court’s "provisional jurisdiction" governing the appealability of orders denying intervention,

19

end of the trial, however, inadequacy of representation was firmly established and movants’

evidence had been placed before the Court, minimizing if not eliminating any delay.

Plaintiffs and proposed intervenors were like the workers in Stallworth, which this Court

described as "a classic example of the type of case in which the rights asserted by two

groups of workers employed by the same defendant should be adjudicated in one action

rather than two," 558 F.2d at 270. TMLS and BPLA urge the Court to hold that the

district court abused its discretion in denying permissive intervention.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth herein, this Court should (1) reverse the district court’s

denial of Appellants’ Motion to Intervene and direct that TMLS and BPLA be granted

intervention in order that they may participate in any future proceedings in this litigation,

and (2) in the event that any aspect of the district court opinion approving the

consideration of race in admissions is reversed or vacated, direct the district court to allow

TMLS and BPLA to present evidence on remand relating to the validity of the Texas Index.

Respectfully submitted,

Anthony P. Griffin

1115 Moody

Galveston, TX 77550

(409) 763-0386

Texas Bar No. 08455300

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

David Van Os

Van Os, White & Vasquez, P.C.

200 East 6th Street

Suite 206

Austin TX 78701

(512) 479-6155

Texas Bar No. 20450700

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W., Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Counsel for Proposed Intervenors-Appellants

see Stallworth, 558 F.2d at 263, and therefore misses the mark.

20

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing Reply Brief for Proposed Intervenors-

Appellants have been served by depositing same in first-class United States mail on this

21st day of February, 1995, addressed as follows:

Steven W. Smith

3608 Grooms Street

Austin, TX 78705

Michael P. McDonald

Center for Individual Rights

1300 19th Street, N.W., #260

Washington, D.C. 20036

Terral R. Smith

100 Congress Ave., #1100

Austin, TX 78768-2023

R. Kenneth Wheeler

Joseph A. Wallace

Paul J. Harris

Wallace, Harris, Sims & Wheeler

1100 Boulders Parkway

Suite 100

Richmond, VA 23225

Counsel for Plaintiffs

Samuel Issacharoff, Esq.

Charles Alan Wright, Esq.

University of Texas School of Law

727 East 26th Street

Austin, TX 78705

Javiar Aguilar, Esq.

Special Assistant Attorney General

209 W. 14th Street

Austin, TX 78701

Harry M. Reasoner, Esq.

Betty Owens, Esq.

Vinson & Elkins

3300 First City Tower

1001 Fannin Street

Houston, TX 77002

R. Scott Placek, Esq.

Barry D. Burgdorf, Esq.

Vinson & Elkins

600 Congress Ave.

Austin, TX 78701-3200

Counsel for Defendants

Norman J. Chachkin

21

APPENDIX A

CHRONOLOGY

September 29, 1992 — Complaint of Cheryl Hopwood filed

April 23, 1993

August 13, 1993

October 28, 1993

Complaint of Plaintiffs Carvell, Elliott, Rogers filed as separate

action [subsequently consolidated with Hopwood on October

12, 1993]

Defendants’ motion for summary judgment on

issues of standing and ripeness filed

District court denies defendants’ motion for summary judgment

on standing and ripeness grounds

[Discovery up to this point was bifurcated and addressed only the issues of standing and

ripeness. Discovery on the merits did not begin until the district court authorized such

discovery on November 17, 1993.]*

November 17, 1993 —

December 18, 1993 -

January 5, 1994

January 20, 1994

January 26, 1994

February 1, 1994

February 7, 1994

February 8, 1994

February 8, 1994

District Court authorizes the parties to begin discovery on the

merits

The first exchange of documents on the merits phase of the

case begins

Proposed Intervenors TMLS and BPLA filed motion to

intervene and by letter from counsel Anthony Griffin,

requested a hearing

District Court denies motion to intervene

Notice of Appeal of the denial of intervention filed

First Amended Complaint filed

Certified Copy of the docket entries lodged by district court

Motion to Expedite Appeal filed by TMLS and BPLA

TMLS and BPLA file motion seeking provisional party status

pending the appeal

‘Prior to October 28, 1993, there was no need for TMLS and BPLA to intervene

because only the standing and ripeness issues were being addressed and a decision on either

of those bases could have eliminated the entire action.

A -l

February 15, 1994 — Order denying motion for provisional party status

February 24, 1994 — Order denying motion to expedite appeal

February 28, 1994 -- Motion to Reconsider the Denial of the Motion to Expedite

the Appeal

March 11, 1994 Motion to Expedite the Appeal granted, with order directing

that the matter be placed on the calendar for the week of May

2, 1994

March 17, 1994 Brief of Proposed Intervenors filed

March 24, 1994 Brief of Plaintiffs in Opposition to intervention filed

March 26, 1994 Reply Brief of Proposed Intervenors filed

May 11, 1994 Court of Appeals decision affirming the denial of intervention

May 16, 1994 Trial begins in the district court

May 24, 1994 District Court states that intervenors will be able to place in

the record any materials they would like

May 25, 1994 Trial ends

June 13, 1994 Post-trial briefs filed, amicus brief on behalf of TMLS and

BPLA with Shapiro Declaration attached filed

June 21, 1994 Plaintiffs move to strike Shapiro Declaration and other

materials attached to amicus brief

June 22, 1994 Motion to Strike denied, district court states that evidence

outside of the trial record will not be considered

July 12, 1994 TMLS and BPLA file a renewed motion to intervene for the

sole purpose of introducing evidence relating to the validity of

the Texas Index

July 18, 1994 Order denying motion to intervene

August 19, 1994 District Court decision on the merits

A-2