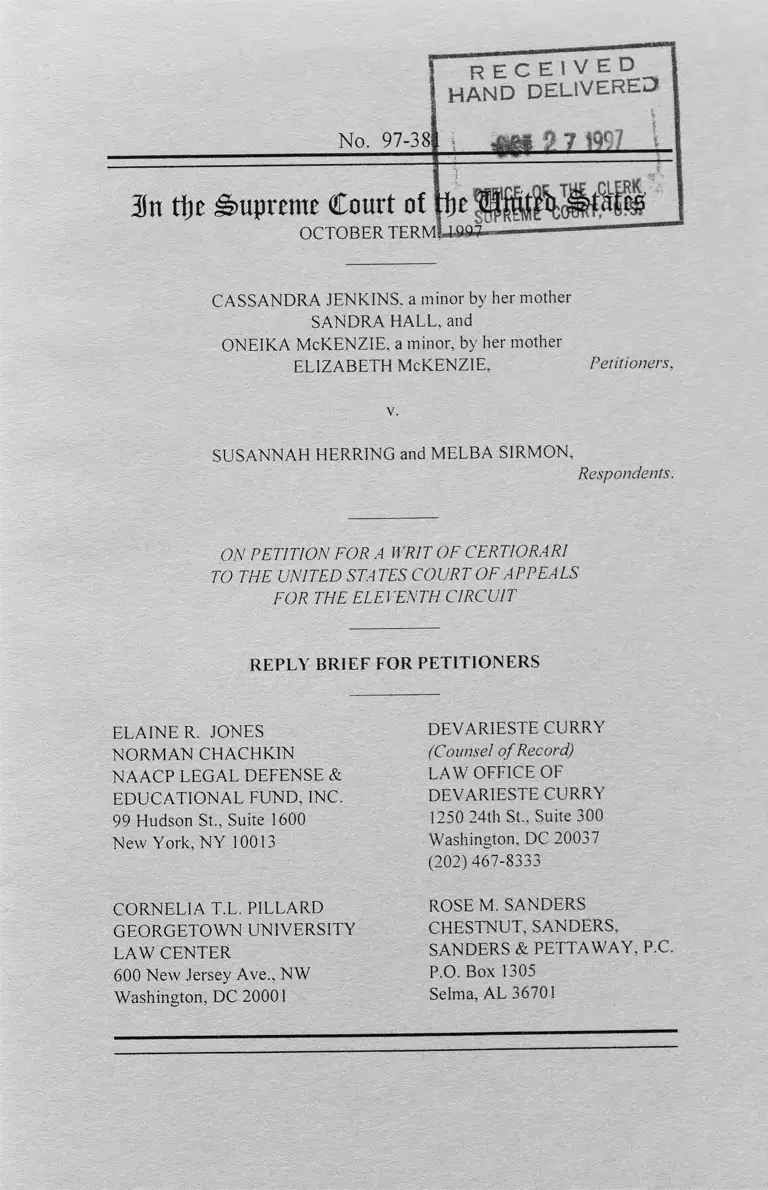

Jenkins v. Herring Reply Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 27, 1997

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jenkins v. Herring Reply Brief for Petitioners, 1997. 9a596aad-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c6e833e6-9aad-40d9-868f-7709c7a866d7/jenkins-v-herring-reply-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

r e c e i v e d

h a n d d e l i v e r e d

No. 97-38 ?. 7 S92_ L

3ftt tijc Supreme Court ot ■ t j e i i t i v *

OCTOBER TERM

CASSANDRA JENKINS, a minor by her mother

SANDRA HALL, and

ONEIKA McKENZIE, a minor, by her mother

ELIZABETH McKENZIE, Petitioners,

SUSANNAH HERRING and MELBA S1RMON,

Respondents.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

ELAINE R. JONES

NORMAN CHACHKIN

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson St., Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY

LAW CENTER

600 New Jersey Ave., NW

Washington, DC 20001

DEVAR1ESTE CURRY

(Counsel o f Record)

LAW OFFICE OF

DEVARIESTE CURRY

1250 24th St., Suite 300

Washington, DC 20037

(202) 467-8333

ROSEM. SANDERS

CHESTNUT, SANDERS.

SANDERS & PETTAWAY, P.C.

P.O. Box 1305

Selma, AL 36701

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities..................................................................ii

Reasons for Granting the W rit............................. 1

Conclusion........................................................... 10

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Anderson v. Creighton, 483 U.S. 635 (1987) ..................... 7

Bellnier v. Lund, 438 F. Supp. 47 (N.D.N.Y. 1977) . . . . . . 5

Bilbrey v. Brown, 738 F.2d 1462 (9th Cir. 1984) ...............5

Courson v. McMillian, 939 F.2d 1479 (11th Cir. 1991) ............3

Doe v. Renfrow, 631 F.2d 91 (7th Cir. 1980)

(per curiam), cert, denied, 451 U.S. 1022 (1981) . . . . . . . 5

Elder v. Holloway, 510 U.S. 510 (1994).......................... 5, 6

State ex rel. Galford v. Mark Anthony B.,

433 S.E.2d 41 (W. Va. 1993)...............................................5

Hamilton v. Cannon, 80 F.3d 1525 (11th Cir. 1996)...........3

Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800 (1982)................. .. . 3, 6

Lassiter v. Alabama A & M Univ.,

28 F.3d 1146 (11th Cir. 1994) (en b a n c ) ............................8

Lebron v. National R.R. Passenger Corp.,

513 U.S. 374(1995)..................................................... 5,6-7

Mitchell v. Forsyth, 472 U.S. 511 (1985) ....................... 8, 9

Monell v. Department o f Social Services,

436 U.S. 658 (1978)................... ......................................... 2

New Jersey v. T.L.O, 469 U.S. 325 (1985) ...............passim

Oliver v. McClung, 919 F. Supp. 1206 (N.D. Ind. 1995) . . . 5

Tarter v. Raybuck, 742 F.2d 977 (6th Cir. 1984),

cert, denied, 470 U.S. 1051 (1985) ....................................5

United States v. Lanier, 117 S. Ct. 1219 (1997) . . . . passim

ii

3n tfje Supreme Court of tfje United States!

October Term, 1997

No. 97-381

Cassandra Jenkins, a minor by her mother

Sandra Hall, and

Oneika Mckenzie, a minor, by her mother

Elizabeth Mckenzie, Petitioners

v.

Susannah Herring and Melba Sirmon

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Respondents’ brief in opposition only confirms that

this case warrants this Court’s review. First, respondents

acknowledge that there is a circuit conflict on the issue of

which jurisidictions’ precedents are to be considered in a

qualified immunity case to determine whether the law was

“clearly established.” Second, respondents do not question our

observations (Pet. 22-24) that every court that has upheld even

a partial strip search in a school setting dealt with a search for

weapons or other dangerous contraband, and that every court

reviewing a strip search for items not posing any imminent risk

of serious harm, such as money, has held the search to be

2

unconstitutional. Instead, respondents suggest that we have

waived reliance on any cases other than New Jersey v. T.L. O,

469 U.S. 325 (1985), that support our contention that

petitioners’ rights were clearly established. There is no factual

or legal basis for that suggestion.

Third, respondents unsuccessfully attempt to reconcile

the decision below with United States v. Lanier, 117 S. Ct.

1219 (1997), by misconstruing Lanier's core holding. The

court of appeals’ insistence that only factually specific, similar

precedents can clearly establish the law cannot be squared with

Lanier's recognition that even cases with “notable factual

distinctions” from the case before the court can clearly

establish the law. Id. at 1227. Fourth, the factual differences

between T.L.O. and this case do not negate the conclusion that

T.L. O. plainly prohibits teachers’ precipitate and repeated strip

searches of eight-year-old students in search of seven dollars

that another student reported missing.' Under respondents’

interpretation of T.L.O., no school search, no matter how 1

1 Respondents seek to downplay the detrimental impact of

the court of appeals’ standard on the enforceability of constitutional

rights by speculating that the contours of students’ Fourth

Amendment rights might become more clearly defined in cases in

which school officials “fail to raise the defense of qualified

immunity,” Br. in Opp. 17 n.l 1, but enforceability of constitutional

rights should not have to turn on defendants’ defaults. Respondents

also suggest that constitutional standards could develop in cases

against school boards, but claims against governmental entities

under 42 U.S.C. 1983 require a showing that the constitutional

violation resulted from an official policy or custom. See Monell v.

Department o f Social Services, 436 U.S. 658, 694 (1978). Such

cases thus cannot clarify T.L.O.'s application to the typical strip

search case, in which no governmental policy or custom is involved.

3

extreme or intrusive, would warrant a finding of liability. They

maintain that “T.L.O. is nothing more than an abstract, general

proposition which provides absolutely no instruction to school

officials as to the permissible scope of student searches.” Br.

in Opp. 21. Certiorari should be granted in this case to dispel

that notion.

1. Respondents concede (Br. in Opp. 15) that there is

“some conflict” among the circuits on the question of which

courts’ decisions are relevant to the determination whether the

law is clearly established under Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S.

800 (1982). Their suggestion (Br. in Opp. 15-17) that the

decision below does not squarely conflict with the decisions of

the First, Third, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, Ninth and Tenth

Circuits, is based on a syllogism. Respondents point out that

the Eleventh Circuit considers some “nonbinding” precedent,

as do decisions of seven other circuits we identified as

conflicting with the decision below. Id. The only nonbinding

precedents the Eleventh Circuit considers, however, are the

decisions of the highest court of the state in which the case

arose.2 The seven other circuits, in contrast, consider

2 The petition stated that the Eleventh Circuit looks only to

“binding” precedent, see Pet. 11, 16, but that characterization is

admittedly an inadvertent oversimplification. The court of appeals

on occasion also looks to the (nonbinding) decisions of the highest

court of the state in which the claim arose. See Pet. 14-15; Hamilton

v. Cannon, 80F.3d 1525, 1531-1532 n.7 (11th Cir. 1996); Courson

v. McMillian, 939 F.2d 1479, 1498 n. 32 (11th Cir. 1991) (holding

that “clearly established law in this circuit may include decisions of

the highest state court in states that comprise this circuit as to those

respective states, when the state supreme court has addressed a

federal constitutional issue that has not been addressed by the United

States Supreme Court or the Eleventh Circuit”).

4

nonbinding decisions from other jurisdictions, including other

circuits, and, in some cases, decisions of district courts, and of

state courts outside of the state where the case arose. See Pet.

16-18 (discussing cases). The decision below thus embraces a

rule to which no other court adheres, and that is materially in

conflict with decisions of at least seven other circuits.3

Respondents erroneously suggest that the application of

a different standard would not have affected the result in this

case because the precedents the court of appeals declined to

consider “[do] not necessarily clearly establish the law.” Br. in

Opp. 16. As we contended in the petition, however, “the

decided school search cases from other jurisdictions as of May

1992, taken together, certainly made petitioners’ rights clear.”

Pet. 18; see id. at 26-27. If the cases from other jurisdictions

had been considered, it would have been evident that

respondents should not have been afforded qualified immunity.

2. Respondents assert (Br. in Opp. 5, 15 n.9, 18 n.12)

that we have conceded that T.L.O. is the sole precedent that

could have clearly established the law. That assertion does not

detract from the certworthiness of this case. First, we made no

such concession. Second, even if we had, it would not amount

3 Indeed, respondents’ brief points out that the conflict is

even more pervasive than we asserted in the petition. See Pet. 18

(describing the Second and Fifth Circuits as substantially in

agreement with the Eleventh Circuit). As respondents note (Br. in

Opp. 15), the Eleventh Circuit’s standard is unique; while the

Second and Fifth Circuits consider only this Court’s and their own

circuit precedents, the Eleventh Circuit also considers decisions of

the highest court of the state where the case arose.

5

to a waiver and would have no effect on this Court’s ability to

consider all relevant cases in support our claim. See Lebron v.

National R.R. Passenger Corp., 513 U.S. 374, 379 (1995);

Elder v. Holloway, 510 U.S. 510 (1994).

Petitioners repeatedly and consistently have relied on

lower court cases, as well as on T.L.O., to support the

contention that petitioners’ rights were clearly established. See

Pet. 26-29 (citing cases). In the briefs to the court of appeals

panel, petitioners cited other relevant cases in addition to

T.L.O. See, e.g., Pet’r C.A. Br. 20-21 & n.6 (citing Doe v.

Renfrow, 631 F.2d 91 (7th Cir. 1980) (per curiam), cert,

denied, 451 U.S. 1022 (1981); Bilbreyv. Brown, 738 F.2d 1462

(9th Cir. 1984)). Before the en banc court, petitioners

continued to assert the relevance of school search cases other

than T.L.O. See, e.g., Pet’r En Banc C.A. Br. 22 n.10, 27 n.13,

35 (citing Doe v. Renfrow, 631 F.2d 91; Tarter v. Raybuck, 742

F.2d 977 (6th Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 470 U.S. 1051 (1985);

Oliver v. McClung, 919 F. Supp. 1206 (N.D. Ind. 1995);

Bellnier v. Lund, 438 F. Supp. 47 (N.D.N.Y. 1977); State ex

rel. Galfordv. Mark Anthony B., 433 S.E.2d41 (W. Va. 1993).

There is thus no basis for respondent’s suggestion that we have

somehow waived reliance on cases other than T.L.Of 4

4 The court of appeals concluded that the parties “agree[d]”

that T.L.O. was the only relevant school-search case and thus was

“the sole precedent that could have clearly established the law for

purposes of qualified immunity analysis.” Pet. App. 6a n.l.

Because the court states that conclusion without citation to the

record, we do not know what comment the court might have been

construing as manifesting our “agreement.” In any event, the court’s

conclusion must be viewed in light of that court’s rule limiting the

universe of relevant cases. In stating that petitioners had identified

no relevant case other than T.L. O., the court of appeals was governed

6

Even if we had failed in the lower courts to identify

relevant cases other than T.L.O., no estoppel or waiver would

have resulted. Rather, we could nonetheless raise, and this

Court could rely on, any cases tending to show that petitioners’

rights were clearly established. As this Court unanimously

held in Elder v. Holloway, “appellate review of qualified

immunity dispositions is to be conducted in light of all relevant

precedents, not simply those cited to, or discovered by,” the

lower courts. 510 U.S. at 512.5 Thus, any failure in the lower

courts to identify cases that help to clearly establish the law

does not affect our ability to identify such cases now. Indeed,

even an affirmative disavowal of reliance on any cases other

than T.L.O. would not have affected our ability to rely on

additional cases in this Court. See Lebron v. National R.R.

by its own rule that only cases from this Court, the Eleventh Circuit

itself and the highest court in the state where the case arose can

“clearly establish” a right within the meaning of Harlow v.

Fitzgerald. See Pet. App. 14a n.3. It is precisely that rule limiting

the universe of relevant cases that conflicts with holdings of other

courts of appeals, and that petitioners challenge in this Court. Pet.

i (Question 3); 14-18. The fact that the court of appeals viewed

petitioners’ contentions through the narrow lens of its own circuit

rule cannot serve to insulate that rule from this Court’s review.

5 In Elder, the plaintiffs failure to call certain precedent to

the district court’s attention did not preclude him from relying on

that precedent in the court of appeals. This Court reasoned that

“[w]hether an asserted federal right was clearly established at a

particular time, so that a public official who allegedly violated the

right has no qualified immunity from suit, presents a question of

law, not one o f ‘legal facts.’” 510 U.S. at 516.

7

Passenger Corp., 115 S. Ct. at 965.6 Under Lebron,

petitioners’ Fourth Amendment claim, and their contention that

the law supporting it was clearly established, are plainly

preserved and appropriate for review by this Court, without

regard to whether some of the arguments petitioners now

present might be new.6 7

3. Respondents’ argument (Br. in Opp. 7-12) that the

Eleventh Circuit standard is consistent with United States v.

Lanier, 117 S. Ct. 1219 (1997), misses the mark. Respondents

contend, in essence, that Lanier and Anderson v. Creighton,

483 U.S. 635, 640 (1987), stand for the same “principles,” and

that the decision below is “commensurate with Anderson,” and

thus with Lanier. Br. in Opp. 10. Respondents are wrong,

however, because both the decision below and Lanier address

an issue not resolved in Anderson, and do so in conflicting

ways.

Anderson held that, “in light of preexisting law, the

unlawfulness [of the challenged conduct] must be apparent,”

6 In Lebron, this Court reviewed an argument that the

petitioners in that case had expressly disavowed in the court of

appeals. See 115 S. Ct. at 964. The Court applied its “traditional

rule” that “[o]nce a federal claim is properly presented, a party can

make any argument in support of that claim; parties are not limited

to the precise arguments they made below.” Lebron, 115 S. Ct. at

965 (quoting Yee v. City o f Escondido, 503 U.S. 519, 534 (1992)).

7 In any event, if any such waiver had occurred, it would

relate only to the third question presented, and would not warrant

denial of certiorari on the other two questions. As we stated in our

petition (Pet. 11, 20-27), T.L.O. on its own sufficed to clearly

establish petitioners’ Fourth Amendment rights.

8

but that “the very action in question” need not have “previously

been held unlawful.” Id. at 640. Anderson did not reach the

question whether, in order to defeat qualified immunity, a

plaintiff must show that factually similar conduct had been held

unlawful. The Eleventh Circuit held that the plaintiff must,

requiring that there be established law developed in “a concrete

and factually defined context” that is “materially similar” to the

challenged conduct. See Pet. App. 5a; Lassiter v. Alabama A

& M Univ., 28 F.3d 1146, 1150 (11th Cir. 1994) (en banc).

This Court in Lanier, in contrast, held that the law can be

clearly established even in the absence of “precedents that

applied the right at issue to a factual situation that is

‘fundamentally similar’” to the claim at issue, and even where

there are “notable factual distinctions between the precedents

relied on and the cases then before the Court.” 117 S. Ct. at

1227. Because the conduct challenged in this case falls at or

near the prohibited end of the constitutional spectrum

established by T.L.O., its unlawfulness is “apparent” under

Lanier even in the absence of any prior, factually similar case.

The Eleventh Circuit’s requirement of factually similar

precedent, and its conclusion that T.L.O. is too dissimilar and

its standard too general to have clearly established the law in

this case, conflict with Lanier.

Respondents seek to reconcile the court of appeals’

requirement of factually specific precedent with Lanier's

contrary holding by pointing to this Court’s caveat in Lanier

that, “when an earlier case expressly leaves open whether a

general rule applies to the particular type of conduct at issue, a

very high degree of prior factual particularity may be

necessary.” 117 S. Ct. at 1227. See Br. in Opp. 10-11 n.7

(citing Mitchell v. Forsyth, 472 U.S. 511, 530-535 (1985)).

T.L.O. did not, however, “expressly leave open” the question

whether strip searches by school personnel seeking small

9

amounts of money based on slim suspicion are constitutional.

An issue is not “expressly” left open unless the Court states that

it is declining to reach the issue.8 If an issue were considered

“expressly” left open under Lanier's caveat simply because the

Court had not explicitly addressed it, the caveat would swallow

Lanier's general rule that factually dissimilar precedent can

clearly establish a constitutional right.

4. Lanier refutes respondents’ argument (Br. in Opp.

19-22) that the generality of the T.L. O. standard, and the factual

dissimilarities between T.L.O. and this case, “preclude[] a

finding of clearly established law.” Id. at 22. The fact that the

T.L. O. standard is flexible and thus “creates uncertainty in the

extent of its resolve to prohibit” intrusions of students’ privacy,

469 U.S. at 381 (Stevens, J., dissenting), does not mean that the

application of the standard is uncertain in every case, as

respondents suggest. Br. in Opp. 20. To be sure, there may be

a relatively broad category of cases toward the middle of the

constitutional spectrum to which the application of T.L.O.

remains unclear. As we have argued (see Pet. 20-27), however,

this is not such a case.

8 As an example, Lanier cites Mitchell, which was a

constitutional challenge to a warrantless domestic national security

wiretap. The cited passage in Mitchell points out that in Katz v.

United States, 389 U.S. 347, 358 n.23 (1967), “the Court was careful

to note that ‘[wjhether safeguards other than prior authorization by

a magistrate would satisfy the Fourth Amendment in a situation

involving the national security is a question not presented by this

case.’” 472 U.S. at 532. That express statement in Katz contributed

to the Mitchell Court’s conclusion that former Attorney General

Mitchell was entitled to qualified immunity. See id. at 535.

10

5. Finally, respondents’ assertions about the factual

record provide no grounds for denial of review. Referring to

the Board of Education’s and Office of Civil Rights’

determinations, and to “inconsistencies” in the girls’ testimony,

respondents suggest that the strip searches never took place.

Br. in Opp. 3.9 The record plainly is adequate, however, to

support the unanimous conclusion of the district court, the

court of appeals panel and the en banc court that a reasonable

jury could have found the facts in petitioners’ favor. See Pet.

App. 2a-4a, 40a-43a, 45a.10

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted.

9 OCR’s own report acknowledged that there was

“conflicting testimony whether the students were actually strip

searched, and that OCR was unable to reach for interview “several”

potential witnesses. See Pet’r C.A. App. 138-140.

10 The en banc court recognized that, despite some

discrepancies, petitioners’ testimony was consistent “with respect to

the assertion that they were asked to remove their clothing while

inside the restroom. Pet. App. 3a. With regard to the putative basis

for conducting the strip searches, respondents contend that

McKenzie had repeatedly asked and been given permission to go to

the restroom after the regular restroom break.” Br. in Opp. 2.

Petitioners, however, dispute whether Herring or Sirmon knew of

those requests when they made the girls strip, see Pet. App. 30a-3 la

& n.l 1, and McKenzie’s restroom trips could not in any event

provide any support for strip searching Jenkins.

Respectfully submitted.

DEVARIESTE CURRY

(Counsel of Record)

ELAINE R. JONES

NORMAN CHACHKIN

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

ROSE M. SANDERS

OCTOBER 1997