Correspondence from Reed to Ganucheau; from Reed to Judges Politz, Clark, and Garza

Public Court Documents

July 26, 1988

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Correspondence from Reed to Ganucheau; from Reed to Judges Politz, Clark, and Garza, 1988. 87967509-f311-ef11-9f89-6045bda844fd. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c734e94d-ea08-4d6d-a427-b6ae9c465c20/correspondence-from-reed-to-ganucheau-from-reed-to-judges-politz-clark-and-garza. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

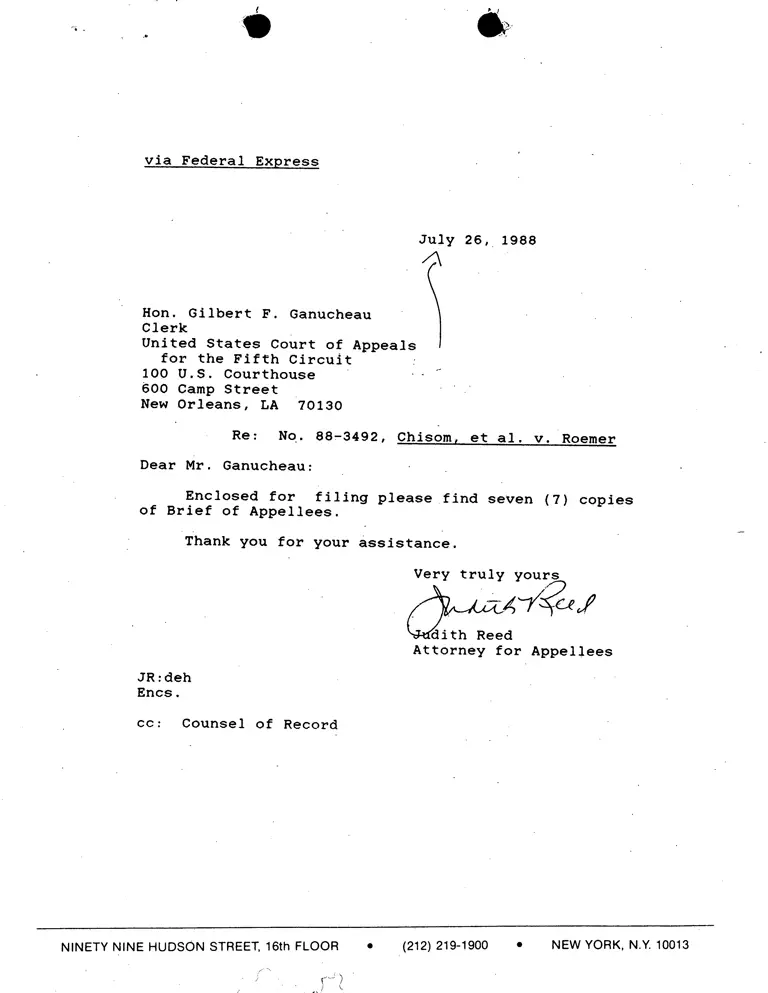

via Federal Express

July 26, 1988

Hon. Gilbert F. Ganucheau

Clerk

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

100 U.S. Courthouse

600 Camp Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

Re: No. 88-3492, Chisom, et al. v. Roemer

Dear Mr. Ganucheau:

Enclosed for filing please find seven (7) copies

of Brief of Appellees.

Thank you for your assistance.

Very truly yours

ce

dith Reed

Attorney for Appellees

JR:deh

Encs.

CC: Counsel of Record

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET, 16th FLOOR • (212) 219-1900 • NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013

via Federal Express

July 26, 1988

The Honorable Henry A. Politz

Circuit Judge

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

Room 2804

500 Fannin Street

Shreveport, LA 71101-3974

Re: No. 88-3492, Chisom, et al. V. Roemer

Dear Judge Politz:

Pursuant to Ms. Joan Perkins' request, we have

enclosed one copy of .the Brief of Appellees filed

today.

Very truly yours,

dith Reed

Attorney for Appellees

JR:deh

Enc.

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET, 16th FLOOR • (212) 219-1900 • NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013

via Federal Express

July 26, 1988

The Honorable Charles Clark

Chief Judge

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

302 U.S. Post Office & Courthouse

244 East Capitol

Jackson, MS 39201

Re: No. 88-3492, Chisom, et al. v. Roemer

Dear Judge Clark:

Pursuant to Ms. Joan Perkins' request, we have

enclosed one copy of the Brief of Appellees filed

today.

Very truly yours,

J dith Reed

Attorney for Appellees

JR:deh

Enc.

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET, 16th FLOOR • (212) 219-1900 • NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013

via Federal Express

July 26, 1988

The Honorable Reynaldo Garza

Senior Judge

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

U.S. Post Office

10th and East Elizabeth Streets

Brownsville, TX 78520

Re: No. 88-3492, Chisom, et al. v. Roemer

Dear Judge Garza:

Pursuant to Ms. Joan Perkins' request, we have

enclosed one copy of the Brief of Appellees filed

today.

Very truly yours,

itAx-4

J ith Reed

Attorney for Appellees

JR:deh

Enc.

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET, 16th FLOOR • (212) 219-1900 • NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013,