Cruz v. United States Brief Amici Curiae in Support of the Petition

Public Court Documents

May 9, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cruz v. United States Brief Amici Curiae in Support of the Petition, 1974. c04db9b5-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c74eade8-cd11-4f36-8f20-618734279106/cruz-v-united-states-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-the-petition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

P U E R T O R IC A N L E G A L D E F E N S E

& E D U C A T IO N F U N D , IN C .

8 1 5 SECOND AVENUE

N E W YORK, N E W YOR K 1 0017

3 1 2 -6 8 7 - 6 6 4 4

VICTOR MARRERO

CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD

CESAR A, PERALES

8XECUTIVE DIRECTOR

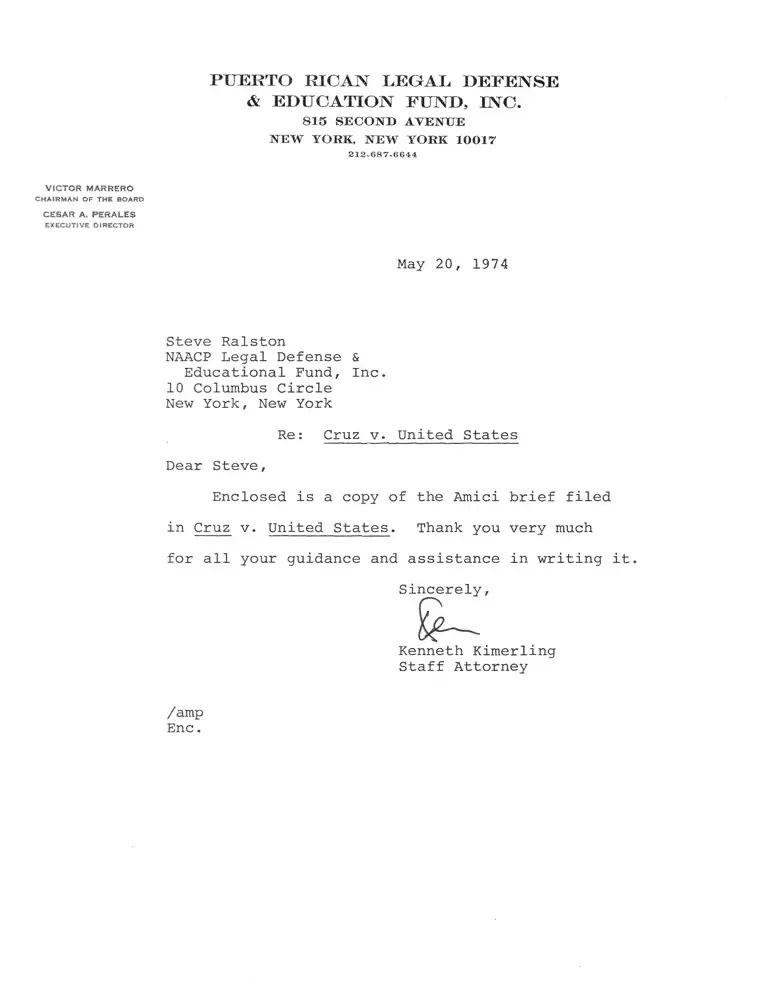

May 20, 1974

Steve Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Re: Cruz v. United States

Dear Steve,

Enclosed is a copy of the Amici

in Cruz v. United States. Thank you

for all your guidance and assistance

Sincerely,

brief filed

very much

in writing it.

Kenneth Kimerling

Staff Attorney

/amp

Enc.

§«jirm r (Emtrt nf % Intipfc H>tat£a

October Term:, 1973

No. 73-6484

I n th e

J ose T orres Cruz and R uben A lberto Y ega y Merced,

Petitioners,

United States oe A merica,

Respondent.

p e t i t i o n e o r w r i t o p c e r t io r a r i t o t h e u n it e d s t a t e s

COURT OE APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE PUERTO RICAN

DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC., AND

THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK

LAWYERS IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITION

Cesar A. P erales

Herbert Teitelbaum

K enneth K imerling

Jose A. R ivera

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

815 Second Avenue

New York, New York 10017

L ennox S. H inds

National Conference of Black Lawyers

126 West 119th Street

New York, New York 10026

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

I N D E X

PAGE

Interest of Amici Curiae ................................................ 1

Preliminary Statement .................................................... 2

Reasons for Granting the W r it :

Introduction ............. 3

Discussion.......... ........................................................ 3

Conclusion........................................................................... 11

Table of A uthorities

Cases:

Aldridge v. United States, 283 U.S. 308 (1931) ............ 4, 8

Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946) .............. 8

Communist Party of U.S.A. v. Subversive Activities

Control Board, 351 U.S. 115 (1956).................... 8

Earn v. South Carolina, 409 U.S. 524 (1965).................. 4

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) ... .................. 4

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948) ................................. 9

Irvin v. Dowd, 336 U.S. 717 (1961) ..........................4, 5, 6, 7

McGlotten v. Connally, 338 P. Supp. 449 (D.D.C.

1972)............................................................................. 4, 9,10

11

PAGE

Patriarca v. United States, 402 F.2d 314 (1st Cir. 1968),

cert, denied, 393 U.S. 1022, rehearing denied, 303 U.S.

1124 (1969) ..................................................................... 6,7

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 723 (1963) ...........'........... 7

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966) .................... 7

Silverthorne v. United States, 400 F.2d 627 (9th Cir.

1968)....................................................................... ......... 6, 7

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ........................... . 9

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ............................. 4

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ........... 3

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1946) ....... 8

United States v. Dellinger, 472 F.2d 340 (7th Cir. 1972) 6

United States ex rel. Bloeth v. Denno, 313 F.2d 364 (2nd

Cir.), cert, denied, 372 U.S. 978 (1963) ...................... 6, 7

Constitution of the United States:

Fifth Amendment ............................................................. 5

Sixth Amendment ............................................................. 5

Miscellaneous:

New York Times, August 13,1973, Section VI, p. 7 4

I n t h e

CEmirt of % Inttefc Stairs

October Term, 1973

No. 73-6484

J ose T orres Cruz and R uben A lberto Y e g a y Merced,

Petitioners,

United States oe A merica,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE PUERTO RICAN

DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC., AND

THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK

LAWYERS IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITION

Interest o f Amici Curiae

The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund,

Inc. (the “PRLDEF” ) is a privately funded, not-for-profit,

New York corporation organized in 1972. Its mandate

includes conducting litigation concerning issues which af

fect the Puerto Rican community as a whole. In that

connection, the PRLDEF has commenced and participated

in lawsuits involving education, voting rights, public as

sistance, migrant labor, employment discrimination, and

2

the administration of justice. The issues presented by

question one of the petition are important issues for the

Puerto Bican community.

The National Conference of Black Lawyers (NCBL) is

an incorporated association of approximately 500 black

lawyers in the United States and Canada, and 2,500 law

students affiliated with NCBL through their membership

in the Black American Law Student Association (BALSA).

Since its inception in December of 1968, NCBL, through

its national office, local chapters, co-operating attorneys

and the BALSA organization has defended black men

and women in the halls of criminal justice, filed civil suits

on behalf of the black community, monitored governmental

activity involving black interests and provided services to

the black bar. The right to have a jury free of racial

prejudice is central to NCBL’s functioning and mandate.

Preliminary Statement

Amici present this brief in support of the petition for

a Writ of Certiorari with consent of all parties, pursuant

to Supreme Court Rule 42 (1). Copies of the letters of

consent are attached to our covering letter to the Clerk

of this Court. Amici rely on petitioners’ treatment of this

Court’s jurisdiction, the questions presented for review,

constitutional and statutory provisions involved and the

statement of the case.

3

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Introduction

The petition for Writ of Certiorari raises an issue of

importance to the Nation and especially to Puerto Ricans,

blacks and other minorities. As framed by petitioners,

the question is whether Puerto Rican defendants were

denied a fair trial by the trial judge’s refusal to grant

challenges for cause to prospective jurors who knowingly

and voluntarily were members of organizations which ex

clude Puerto Rican and black persons. Petitioners have

adequately briefed the issue whether the status of member

ship in discriminatory organizations is a sufficient basis

for challenge for cause. Accordingly, amici will address

another issue included in the question presented—i.e.

whether the inference of racial prejudice resulting from

membership in an organization which discriminates on

the basis of race requires the same type of probing of

prospective jurors as does the inference of prejudice

caused by extensive pre-trial publicity. This question,

which is a novel one for this Court, has importance not

only because of its constitutional dimensions, but also

in regards to this Court’s supervisory powers over the

federal judiciary. Accordingly, review is warranted.

Discussion

Racial prejudice in the jury process has long been an

area of concern for this Court. Almost a hundred years

ago, it struck down a “whites only” jury system in the

State of West Virginia. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U.S. 303 (1880). This decision has been constantly re

4

inforced by the Court. See e.g. Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S.

128 (1940); Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954).

The Court has also mandated that inquiries into the

racial prejudices of prospective jurors be allowed. Al

dridge v. United States, 283 U.S. 308 (1931). This directive

was recently extended to the state courts under the Four

teenth Amendment. Ham v. South Carolina, 409 U.S. 524

(1965).

This Court’s attempt to keep the jury process free

from racial prejudice was undermined by the trial court’s

ruling below. Eight prospective jurors admitted under

questioning that they were members of an organization

which excludes Puerto Ricans and blacks—the Benevolent

and Protective Order of Elks. The Elks, under their con

stitution, have a “whites only” membership policy. See,

McGlotten v. Connally, 338 F. Supp. 449, 450 fn. 1 (D.D.C.

1972). This discriminatory policy is not simply a vestige

of a now renounced past, but was reaffirmed through three

recent membership votes.1 Moreover, the policy is not

benign but is based on a philosophy of racial supremacy.

McGlotten v. Connally, supra at 454.

Membership in a discriminatory organization is a status

which creates an inference of racial prejudice. Once this

inference is raised, it must be overcome through an in

depth probe of the individual prospective juror in order

to protect petitioners’ rights to “ a panel of impartial, ‘in

different’ jurors.” Irvin v. Dowd, 336 U.S. 717, 722 (1961).

1 New York Times, August 13, 1972, Section VI, p. 7. The vot

ing was held at the annual membership conferences in 1968, 1969,

1971 and 1972, and each time an amendment to change the whites

only membership clause in the constitution was defeated.

5

That inference was not overcome in this case, and the

judge’s denial of petitioners’ challenges for cause violated

their Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights.2

It was not sufficient to ask the jurors whether or not

membership in the Elks “ [w]ould . . . in any wav cause

you to be prejudiced in hearing this type of criminal case,

where the defendants are Puerto Rican!” [Trial Tran

script p. 57]. Assurances of impartiality in response to such

general questions do not remove the taint of prejudice from

these prospective jurors who have segregated their social

lives with a “whites only” policjv

The influence that lurks in opinion once formed is so

persistent that it unconsciously fights detachment from

the mental process of the average man. Irvin v. Dowd,

supra at 727.

The trial judge recognized the futility of these general

inquiries made in the presence of the whole jury panel.

Mr. Amsterdam: Frankly, I don’t think that peo

ple may respond affirmatively to some of the ques

tions unless they are asked in an individual way. I

mean, you see one person standing among 54, saying

that he would regard the testimony of Puerto Ricans

with less weight than whites—I don’t think he would

say that in the presence of the other people.

2 The need for close scrutiny to exclude racially prejudiced

prospective jurors was of particular importance herein because

the crimes of which petitioners were accused arose out of the racial

disorders in Hartford, Connecticut in 1970. Moreover, not only

were the jurors going to be called on to decide the guilt or inno

cence of Puerto Rican defendants, but also to determine the credi

bility of Puerto Rican and black witnesses called by petitioners.

6

The Court: He probably wouldn’t say it on the

jury stand, either. But, we have already implanted

the seed, for your purposes to protect the Defen

dants, because that is the real purpose of establishing

a relationship with jurors, as you know. [Trial Tran

script p. 67.]

The Court below had a duty to inquire further than “ . . .

merely going through the form of obtaining jurors’ assur

ances of impartiality.” United States ex ret. Bloeth v.

Denno, 313 F.2d 364, 372 (2nd Cir.), cert, denied, 372 U.S.

978 (1963).

Once the inference of prejudice is raised, there should

be a duty on the trial court to probe those tainted with

prejudice individually outside of the presence of others.

The court should not seek out general assurances of im

partiality but should probe with more particularized ques

tions which would draw out the hidden prejudices of the

prospective jurors. Irvin v. Dowd, supra at 728 ;3 Silver-

thorne v. United States, 400 F.2d 627, 639 (9th Cir. 1968) ;

United States v. Dellinger, 472 F.2d 340, 374 (7th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied, 410 U.S. 970 (1973); Patriarca v. United States,

402 F.2d 314, 318 (1st Cir. 1968), cert, denied, 393 U.S. 1022,

rehearing denied, 393 U.S. 1124 (1969). This was not done

in the instant case despite requests by counsel for individual

questioning of the jurors [Trial Transcript p. 67] and the

submission of a large number of voir dire questions to as

sist the court’s probe of the panel [Becord, Document 42],

3 “No doubt each juror was sincere when he said he would be

fair and impartial to petitioner, but the psychological impact re

quiring such declaration before one’s fellows if often its father.” Id.

7

In the past this Court has established a duty upon lower

courts to probe for prejudice when there has been a show

ing of extensive pretrial publicity. Irvin v. Dowd, supra;

Bideau v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 723 (1963); Sheppard v. Max

well, 384 U.S. 333 (1966). These decisions have been inter

preted by the circuit courts to require a careful examina

tion of each prospective juror by the trial courts. United

States ex rel. Bloeth v. Denno, supra at 372; Silvertkorne

v. United States, supra at 639-640; United States v. Del

linger, supra at 374-375; Patriarca v. United States, supra

at 318. As the court said in Silvertkorne v. United States,

supra:

Recognizing that “we must spare no effort to secure

an impartial panel,” United States v. Dennis, 183 F.2d

201, 226 (2nd Cir. 1950) aff’d 341 U.S. 494, 71 S. Ct.

857, 95 L.Ed. 1137 (1951), we conclude the least re

quired of the district court was to conduct a careful

examination of each of the jurors.

̂ ̂ ^

The defendant in a criminal case has the right to

“probe for the hidden prejudices of the jurors.” Lurd-

ing v. United States, 179 F.2d 419, 421 (6th Cir. 1950).

Id. at 639-640.

The duty to probe the prejudices of prospective jurors

should be no less when there is a showing of a status which

creates an inference of racial prejudices than where there

is pretrial publicity which creates an inference of impar

tiality. The issues raised concerning the duty of a trial

court to probe for racial prejudice in prospective jurors

who admit membership in discriminatory organizations

8

strikes at the heart of the jury system as envisioned by the

Constitution and requires a pronouncement from this Court.

Moreover, because of the constitutional dimensions of

the questions presented, this Court should exercise its

supervisory powers over the federal court system in order

to insure that every step is taken to prevent prejudice in

the jury box.4 The duty to remove the taint caused by the

trial judge’s denial of the challenges in this case is clear:

The untainted administration of justice is certainly

one of the most cherished aspects of our institutions.

Its observance is one of our proudest boasts. This

Court is charged with supervisory functions in relation

to proceedings in the federal courts. See McNabb v.

United States, 318 U.S. 332, 87 L.ed. 819, 63 S. Ct. 608.

Therefore, fastidious regard for honor of the adminis

tration of justice requires the Court to make certain

that the doing of justice be made so manifest that only

irrational or perverse claims of its disregard can be

asserted. Communist Party of TJ.S.A. v. Subversive

Activities Control Board, 351 U.S. 115, 124 (1956).

As in Communist Party of TJ.S.A. petitioners are con

cerned with a lower court’s discretionary decisions which

severely affect the administration of criminal justice. The

issues raised herein are neither irrational nor perverse.

Additionally, the taint caused by the trial court’s denial

of petitioners’ challenge spreads beyond the instant case

4 The Supreme Court in the past has exercised its supervisory

powers to correct discrimination in the jury system. Aldridge v.

United States, supra; Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217

(1946); Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946).

9

and infects the whole federal judiciary. The decision not

to intensively probe these prospective jurors legitimizes

the private discrimination practiced by the Elks by per

mitting its members to participate in judicial processes to

which their prejudices directly and adversely relate. See

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), and Hurd v. Hodge,

334 U.S. 24 (1948); McGlotten v. Connolly, supra. It is

incumbent upon this Court to disinvolve the federal courts

from the segregation practiced by Elks and similar organ

izations. Judge Bazelon, speaking for the three-judge court

in McGlotten, stated, generally, the responsibility of gov

ernment to carefully scrutinize situations where private

discrimination intermingles with government action:

Better than one hundred years ago, this country

sought to eliminate race as an operative fact in deter

mining the quality of one’s life. The decision has yet

to be fully implemented. As Mr. Justice Douglas has

pointedly stated: “ Some badges of slavery remain

today. While the institution has been outlawed, it has

remained in the minds and hearts of many white men.”

The minds and hearts of men may be beyond the pur

view of this or any other court; perhaps those who

cling to infantile and ultimately self-destructive no

tions of their racial superiority cannot be forced to

maturity. But the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments

do require that such individuals not be given solace in

their delusions by the Government. Nor is this em

phasis on the conduct of the Government misplaced.

“ Government is the social organ to which all in our

society look for the promotion of liberty, justice, fair

and equal treatment, and the setting of worthy norms

and goals for social conduct. Therefore something is

10

uniquely amiss in a society where the government, the

authoritative oracle of community values, involves

itself in racial discrimination.” Where that involve

ment is alleged, the courts have exercised the most

careful scrutiny to ensure that the State lives up to

its own promise. [Footnotes omitted.] McGlotten v.

Connally, supra, at 454-455.

This Court should require detailed questioning of prospec

tive jurors belonging to segregated organizations with

policies of racial superiority in order to avoid even the

appearance of the federal judiciary’s legitimizing the “ in

fantile and ultimately self-destructive notions of their racial

superiority.” Id.

11

CONCLUSION

The issues raised are important ones calling into ques

tion whether or not the trial judge had a duty to inquire

in depth into the racial prejudices of prospective jurors

where membership in a discriminatory organization raised

the inference of prejudice. These issues also bring into

question whether the whole federal court system is tainted

when, without any substantial probing by the trial court,

admitted segregationists are allowed to sit on juries judg

ing those against whom they discriminate. Amici respect

fully request that petitioners’ Writ of Certiorari be granted.

Dated: New York, New York

May 9, 1974

Respectfully submitted,

C e s a r A. P e r a l e s

H e r b e r t T e it e l b a t t m

K e n n e t h K im e r l in g

J ose A. R iv e r a

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

815 Second Avenue

New York, New York 10017

L e n n o x S. H in d s

National Conference of Black Lawyers

126 West 119th Street

New York, New York 10026

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

RECORD PRESS, INC., 95 MORTON ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10014— (212) 243-5775

10608 CROSSING CREEK RD., POTOMAC, MD. 20854— (301) 299-7775

38