Beauharnais v. The People of the State of Illinois Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

May 9, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Beauharnais v. The People of the State of Illinois Petition for Rehearing, 1952. e81d8e12-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c7873566-445a-4d79-ae15-080c70b0dd70/beauharnais-v-the-people-of-the-state-of-illinois-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

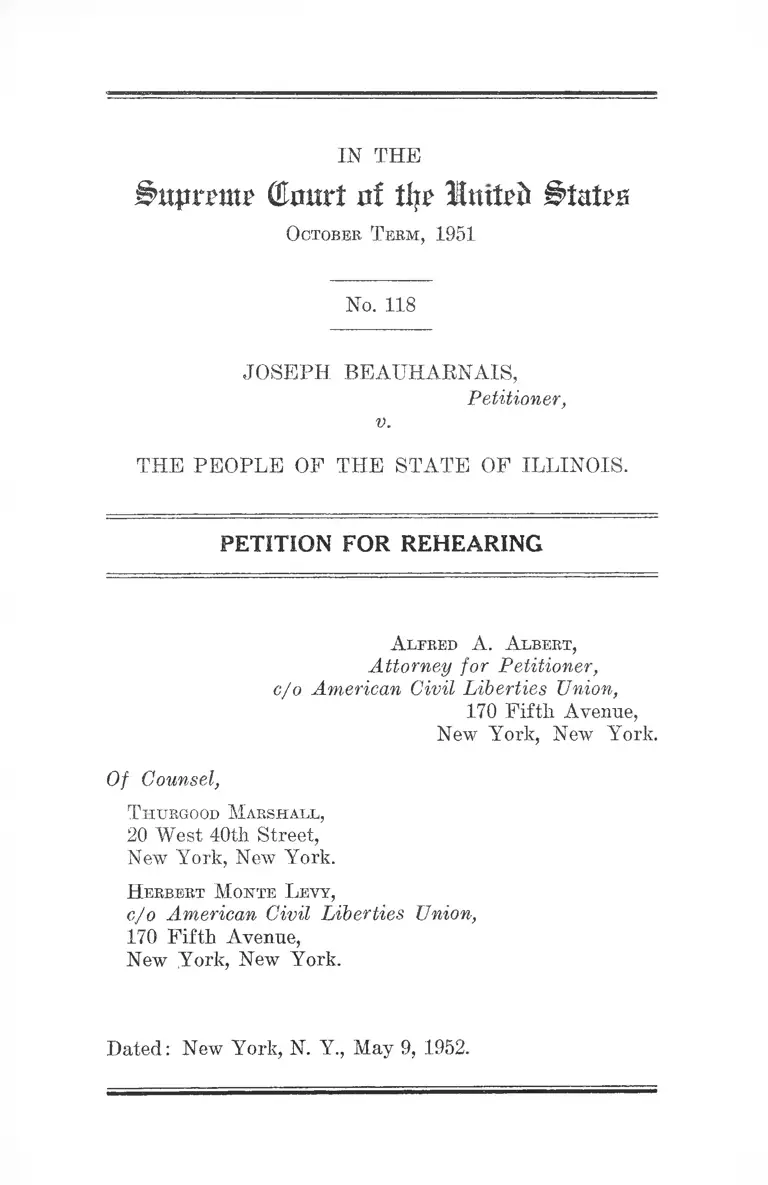

IN THE

^uprTutT ( ta r t nf tfyr Imfrtt #tatrn

October Term, 1951

No. 118

JOSEPH BEAUHARNAIS,

v.

Petitioner,

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS.

PETITION FOR REHEARING

Alfred A. Albert,

Attorney for Petitioner,

c/o American Civil Liberties Union,

170 Fifth Avenue,

New York, New York.

Of Counsel,

T hukgood M a r sh a ll ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York.

H erbert Monte Levy,

c/o American Civil Liberties Union,

170 Fifth Avenue,

New York, New York.

Dated: New York, N. Y., May 9, 1952.

I N D E X

PAGE

Introductory ................................................................ 1

Point I—The Court decided that utterances libelling

groups were not within the area of constitutionally

protected speech, though this proposition had never

been pressed upon it, and though the point was a

novel one never before decided by this Court...... 2

(A) Decision on an issue of such momentous

implications not pressed before the Court should

not be made without full argument ................... 2

(1) This question was never pressed before

the Court ...... ................ ..................... ...... 2

(2) The question thus decided without argu

ment is a monumental one ........................ 4

(B) The decision on this point is the first

holding of this Court on this issue; while sup

portable by dicta it is directly contrary to a

more recent holding by this Court and impliedly

overruled three major recent decisions .............. 5

Conclusion ............................................................................ 9

Certificate of Counsel ..................................... 9

T a b le o f C ases C ited

American Communications Assn. v. Bonds, 339 U. S.

382 ................................................................ 6

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ..... ...............6-7, 8

Commonwealth v. Feiqenbaum, 166 Pa. Super. 120,

70 A. 2d 389 ......... ...................... ........„„................ 6

Commonwealth v. Gordon, 66 Pa. Dist. & Co. E. 101

(1949) (same) ......... 6

11

PAGE

Dennis v. U. 8., 340 U. S. 494 ................................... 6

Doubleday & Co., Inc. v. New York, 335 U. S. 848..... 6

Doubleday and Co., Inc. v. New York, No. 11, Octo

ber Term 1948 (same) .............................................. 6

Douglas v. City of Jeanette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943)...... 7, 8

Runs v. N. Y., 340 IT. S. 290 ..................................... 7, 8

Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 (1949)

3,4, 7, 8

C onstitutional Provisions, S ta tu te and

C om m entaries C ited

United States Constitution:

First Amendment ................................................. 7, 8

Fourteenth Amendment ....................... ............... 2, 8

Illinois Penal Code, Section 224a of Division 1 .......... 1

Arguments before the (Supreme) Court:

" 20 U. S. Law Week 3143, col. 2 .......................... 5

20 U. S. Law Week 3141 ff. ............................. 3

IN THE

^uprem? Court of tlir luttrl* #tatru

October T erm, 1951

No. 118

----------------- IBM ♦ — . -----------------

J oseph B eatjharnais,

Petitioner,

v.

T he P eople oe the State of I llinois.

PETITIO N FOR REHEARING

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice and the Associate

Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States:

Tour petitioner, Joseph Beauharnais, respectfully peti

tions for a rehearing of the decision of this Court in this

case on April 28, 1952, which affirmed petitioner’s con

viction for violation of Section 224a of Division 1 of the

Illinois Penal Code.

This petition requests a rehearing solely on the holding

of this Court that, “ Libellous utterances, not being within

the area of constitutionally protected speech, it is unneces

sary, either for us or for the State courts, to consider

the issues behind the phrase ‘clear and present danger.’ ”

P. 16, Slipsheet Opinion. (All page references hereinafter

are to the Slipsheet Opinion unless otherwise indicated.)

We do not ask for a rehearing on this Court’s decision

that the standards laid down by the statute are sufficiently

2

definite to meet the constitutional requirements of the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This

question was presented to the Court by the parties’ briefs,

was argued thoroughly at the oral argument; though the

decision held against us, we would deem a rehearing on

this point inappropriate. However, the contention that

utterances libelling groups are not within the area of

constitutionally protected speech was not pressed on the

Court in briefs or in oral argument. We suggest that a

rehearing is appropriate under such circumstances, par

ticularly when as here, the holding is not merely a re

affirmation or new application of a prior holding, but is

completely novel. We suggest that a rehearing is par

ticularly appropriate here because, although this holding

of this Court is supportable by older clicta, there is other

and later dicta which is contra, and because the decision

of this Court has impliedly overruled prior decisions of

this Court in at least three major cases, and has over

ruled this Court’s express decision in another major case.

PO IN T I

The Court decided th a t utterances libelling groups

were not w ithin the area of constitutionally protected

speech, though this proposition had never been pressed

upon it, and though the point was a novel one never

before decided by this Court.

(A ) D ecision on an issue o f such m om entous im p lica

tions not p ressed b efo re th e Court shou ld not b e m ad e

w ith ou t fu ll argum ent.

( 1 ) T his question w a s n ever p ressed b efo re th e Court.

Petitioner’s brief took the position that the contents

of petitioner’s diatribe were constitutionally protected.

3

Respondent denied this only formally in two short para

graphs without citation of a single case in point (Re

spondent’s Brief, p. 4). Counsel recollects that this

proposition of law was not denied by Illinois on the oral

argument, nor did any of the Justices of this Court take

petitioner’s counsel to task for having alleged this propo

sition. See Arguments before the (Supreme) Court, 20

IT. S. Law Week 3141 If. The Supreme Court of Illinois

indeed had held that the clear and present danger was

applicable (R. 39-40 ).1

The Court thus decided a question not argued before

it. We need look no further than the opinion in this case

for authority that this Court should not decide questions

not pressed upon it by the parties. This Court stated

on page 14:

“ Neither by proffer of evidence, requests for in

structions, motion before or after verdict did the

defendant seek to justify his utterance as ‘fair

comment’ or as privileged. Nor has the defendant

urged as a ground for reversing his conviction in

this Court that his opportunity to make those

defenses was denied below. And so, whether a

prosecution for libel of a racial or religious group

is unconstitutionally invalid where the State did

deny the defendant such opportunities is not before

us.”

Three of the Justices of the Court who subscribe to the

majority opinion in the case at bar (Mr. Chief Justice

Vinson, Mr. Justice Frankfurter, and Mr. Justice Burton)

vigorously contended in Terminiello that a decision of

1 Our contentions were that (1) the test was improperly applied

(2) in the absence of a finding by the trial court or jury of the exist

ence of a clear and present danger.

4

this Court on the basis of points not raised before it in

any stage of the proceedings nor raised below was im

proper. Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 (1949).

( 2 ) T h e qu estion thus d ec id ed w ith ou t argum ent is a

m onum ental one.

This decision sustains the constitutionality of all state

criminal libel laws, individual and group, in the absence of

a clear and present danger.2 All this without a hearing

having been had on this issue, and without any prior

holding by the Court to this effect. Counsel for peti

tioner share the fears of Mr. Justice Black and Mr. Justice

Douglas that a weapon has now been given to enemies of

minority groups. Without a requirement of a finding of

a clear and present danger there is no way in which this

Court could ever overturn a conviction for criminal libel

in any of the instances set forth on page 8 of Mr. Justice

Black’s opinion and page 3 of Mr. Justice Douglas’

opinion.

The majority was careful to point out that it would

not decide the issue of constitutionality of outlawry of

libels of political parties. But of course, political parties

are not exempt from being prosecuted under the Illinois

group libel law here sustained. Thus political advocacy

might be restricted even under this decision. If libellous

utterances are not within the area of constitutionally pro

tected speech as this Court holds, one may inquire whether

any free speech question would be raised if libel of political

parties were outlawed. While this Court points out that

in such a situation “ the whole doctrine of fair comment

as indispensable to the democratic political process would

come into play” (p. 13, fn. 18), this Court also pointed

2 A group libel law has been introduced into the House of Repre

sentatives since this Court’s decision in this case.

5

out that the defense of fair comment was protected by the

Illinois law here (p. 14, fn. 19). Thus the one distinction

suggested by the Court is an irrelevant one. Certainly

“ the whole doctrine of fair comment as indispensable to

the democratic political process” is involved in this statute

since it penalizes utterances even when made by political

parties. We can see no basis upon which this Court could

later hold constitutional a law outlawing libels of political

parties unless it were to do so on the due process ground

that it would be “ a wilful and purposeless restriction

unrelated to the peace and well-being of the State” (p. 8).

In view of the long history of political conflict in the state

of Illinois, we find it difficult to comprehend how this Court

could upset such a statute of Illinois if it came before it.

We point out that Illinois conceded on the oral argument

that if this statute would be upheld, a statute outlawing

libels of political parties would also have to be held con

stitutional.3

(B ) T h e d ec is io n on th is point is th e first h o ld in g o f

th is Court on th is is su e ; w h ile su p p ortab le by d ic ta i t is

d ir e c t ly c o n tr a ry to a m ore r e c e n t h o ld in g b y th is Court

a n d im p lie d ly o v e r ru le d th r e e m ajor recen t decisions.

We do not deny that clicta exist to the effect that libel

lous words—directed against an individual—can be crim

inally punished without raising a constitutional problem.4

3 In this connection it is interesting to note that while Illinois

was asked by Mr. Justice Black to include, in its memorandum on

labor and racial violence in Illinois, the record of political riots (20

U. S. Law Week 3143, col. 2), no such record was included.

4 As this Court stated, it has also been stated in dictum that

obscenity is exempted from constitutional protection. But this Court

was in error when it stated that “Certainly no one would contend

that obscene speech * * * may be punished only upon a showing

of such circumstances (of clear and present danger).” P. 16. For

it was squarely held by Judge Curtis Bok that obscenity could not be

6

However, the most recent dicta on the subject are directly

contra. Thus, in American Communications Assn. v.

Bonds, 339 U. S. 382, at 412, Mr. Chief Justice Vinson

stated that an individual is “ permitted to advocate what

he will” (emphasis supplied) in the absence of the exis

tence of a clear and present danger, and this Court in

Dennis v. U. S., 340 U. S. 494 at 510, adopted the rule as

laid down below that “In each case fcourts] must ask

whether the gravity of the ‘evil’, discounted by its im

probability, justified such invasion of free speech as is

necessary to avoid the dangers.” (Emphasis supplied.)

While agreeing with the majority in Dennis holding that

advocacy of revolution is constitutionally protected, we

wonder upon what rationale such speech is protected by

constitutional guarantees whereas libellous statements of

groups are not.

Moreover, the decision in this case is directly contra

to this Court’s decision in Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310

punished except upon a showing of such circumstances. Common

wealth v. Gordon, 66 Pa. Dist. & Co. R. 101 (1949). This test was

expressly approved and Judge Bok’s decision upheld by the Superior

Court of Pennsylvania sub nom. Commonwealth v. Feigenbaum,

166 Pa. Super. 120, 70 A. 2d 389. The Supreme Court of Penn

sylvania denied leave to appeal in an unreported per curiam order

on March 30, 1950, which read as follows: “Allocatur refused, with

out, however, approving the test of ‘clear and present danger’ as ap

plied to alleged obscene literature adopted by Judge Bok in the

Quarter Sessions and apparently approved by the Superior Court.”

It should be noted that the Court did not disapprove of the test.

In addition, it was contended before this Court in a brief of the

American Civil Liberties Union as amicus curiae in Doubleday and

Co., Inc. v. New York, No. 11, October Term 1948, that obscene

speech could not be punished except upon a showing of such circum

stances. Whether this Court ever ruled upon this contention is

impossible to say, for the decision below was affirmed by an equally

divided Court without opinion. Doubleday & Co., Inc. v. New York,

335 U. S. 848. Of course, the question of the limitation of obscenity

by the clear and present danger test need not be decided in this case

in any event.

7

U. S. 296, holding that language denouncing the Boman

Catholic Church as “ an instrument of Satan” was pro

tected by the First Amendment. Said this Court at

page 310,

“ In the realm of religious faith, and that of political

belief, sharp differences arise. In both fields the

tenets of one may seem the rankest error to his

neighbor. To persuade others to his own point of

view the pleader, as we know, at times, resorts to

exaggeration, to vilification * * *, and even to

false statement. But the people of this nation have

ordained in the light of history, that, in spite of

the probability of excesses and abuses these liber

ties are, in the long view, essential to enlightened

opinion and right conduct on the part of the citizens

of a democracy.” (Emphasis supplied.)

In Douglas v. City of Jeanette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943), the

constitutional guarantee of free speech was held to apply

to a description of the Boman Catholic Church organiza

tion as a “ harlot” .

In Kunz v. N. Y., 340 U. S. 290, this Court held that the

guarantee of the First Amendment applied to an address

delivered on the streets of New York vilifying Jews as

“ Christ-Killers.”

In Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 (1949),

this Court held the constitutional guarantee of free speech

applicable to language much more libellous of racial and

religious groups than the language in question here. For

example, as quoted from the dissenting opinion of Mr.

Justice Jackson, Terminiello stated, “ I said, ‘Fellow

Christians’ and I suppose there are some of the scum

got in by mistake, * * * the slimy scum.” He accused

the Jews of wanting to inject syphilis and other diseases

into non-Christians. Jews were called Communistic. Id.

8

at 17, 20. This Court held this speech to be within the pro

tection of the First Amendment.

Thus the Court has on these four occasions held words

libellous of racial and religious groups to be protected by

the First and Fourteenth Amendments. It never held

nor stated otherwise. Whatever the dicta of this Court

on the constitutionality of criminal libel laws directed

against libels of individuals, this Court never before

passed upon whether criminal libel laws directed against

members of groups are constitutional, but in each of the

cases listed above—in Cantwell, in Kunz, in Douglas, in

Terminiello—it consistently upheld the constitutional pro

tection of free speech for words libellous of racial and

religious groups, whatever the form of the statute under

which the case arose.5 The decision in the instant case

thus necessarily overrules each of the four mentioned

above. We submit that irrespective of whether or not

such an overruling is now justified, it should not be done

without any argument on the issue having been presented

to the Court. We submit that a rehearing is most cer

tainly necessary in this case.

5 The Court analogized the prevention of libellous utterances to

that of obscene speech. We submit that the analogy is without foun

dation. Obscenity never touches upon the political or social issues

of the day. But group libel most certainly does. Comments such as

Beauharnais engaged in were, while thoroughly repulsive to the

members of this Court and to all counsel involved in the case before

it, none the less comments on the burning political and social issues

of the day. The same cannot be said for obscenity.

9

CONCLUSION

This petition for a rehearing should be granted and

the judgment below reversed.

Dated: New York, New York

May 9, 1952.

Respectfully submitted,

Alfred A. Albert,

Attorney for Petitioner,

c/o American Civil Liberties Union,

170 Fifth Avenue,

New York, New York.

Of Counsel,

T httrgood Marshall,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, N. Y.

H erbert Monte L evy,

c/o American Civil Liberties Union,

170 Fifth Avenue,

New York, New York.

Certificate of Counsel

Alfred A. Albert, T httrgood Marshall and H erbert

Monte Levy, counsel for petitioner in this case, hereby

certify tha t this petition for rehearing is presented in

good faith and not for delay.

Alfred A. Albert,

T hurgood Marshall,

H erbert Monte Levy,

Counsel for Petitioner.