Civil Rights Attorneys Ask Protection of Negro Nurses

Press Release

November 24, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 3. Civil Rights Attorneys Ask Protection of Negro Nurses, 1965. a17c4b7d-b692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c808c8c7-00f9-4a67-a049-e18ecdd3d1ce/civil-rights-attorneys-ask-protection-of-negro-nurses. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

New York,

JUdson 6-8397

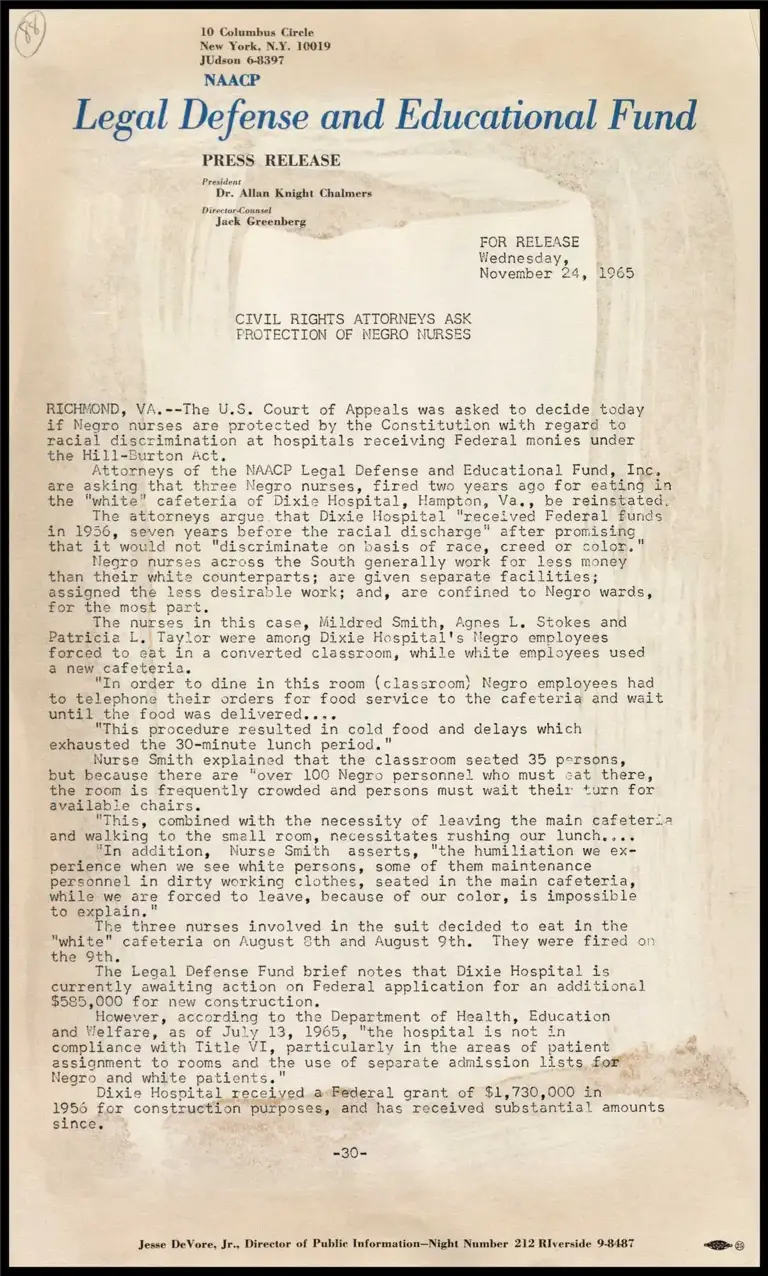

Legal Defense and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

opr. Atlan Knight Chalmers

Director-Counsel

Jack Greenberg

FOR RELEASE

Wednesday,

November 24, 1965

CIVIL RIGHTS ATTORNEYS ASK

PROTECTION OF NEGRO NURSES

RICHMOND, VA.--The U.S. Court of Appeals was asked to decide today

if Negro nurses are protected by the Constitution with regard to

racial discrimination at hospitals receiving Federal monies under

the Hill-Burton Act.

Attorneys of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

are asking that three Negro nurses, fired two years ago for eating in

the “white” cafeteria of Dixie Hospital, Hampton, Nece be reinstated.

The attorneys argue. that Dixie Hospital “received Federal funds

in 1956, seven years before the racial discharge" after promising

that it would not "discriminate on basis of race, creed or color."

Negro nurses across the South generally work for less money

than their white counterparts; are given separate facilities;

assigned the ss desirable work; and, are confined to Negro wards,

for the most part.

The nurses in this case, Mildred Smith, Agnes L. Stokes and

Patricia L, Tay or were among Dixie Hosp. its Negro employees

forced to ¢ in a converted classroom, while white employees used

a new cafeteri .

"In order to dine in this room (classroom) Negro employees had

to telephone their orders for food service to the cafeteria and wait

until the food was delivered....

"This procedure resulted in cold food and delays which

exhausted the 30-minute lunch period.”

Nurse Smith explained that the classroom seated 35 persons,

but because there are “over 100 Negro personnel who must cat there,

the room is frequently crowded and persons must wait their turn for

available chairs.

"This, combined with the necessity of leaving the main cafeteria

and walking to the small room, necessitates rushing our Weeds.

"In addition, Nurse Smith asserts, "the humiliation we ex-

perience when we see white persons, some of them maintenance

personnel in dirty working clothes, seated in the main cafeteria,

while we ar e forced to leave, because of our color, is impossible

to explain.’

The three nurses involved in the suit decided to eat in the

"white" cafeteria on August Sth and August 9th. They were fired on

the 9th.

The Legal Defense Fund brief notes that Dixie Hospital is

currently awaiting action on Federal application for an additional

$585,000 for new construction.

However, according to the Department of Health, Education

and Welfare, as of July 13, 1965, "the hospital is not in

compliance with Title VI, particularly in the areas of patient oe

assignment to rooms and the use of separate admission lists for

Negro and white patients,"

Dixie Hospital received.a«Pederal grant of $1,730,000 in

1956 for construction purposes, and has received substantial amounts

since,

e306

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 Riverside 9-8487 So