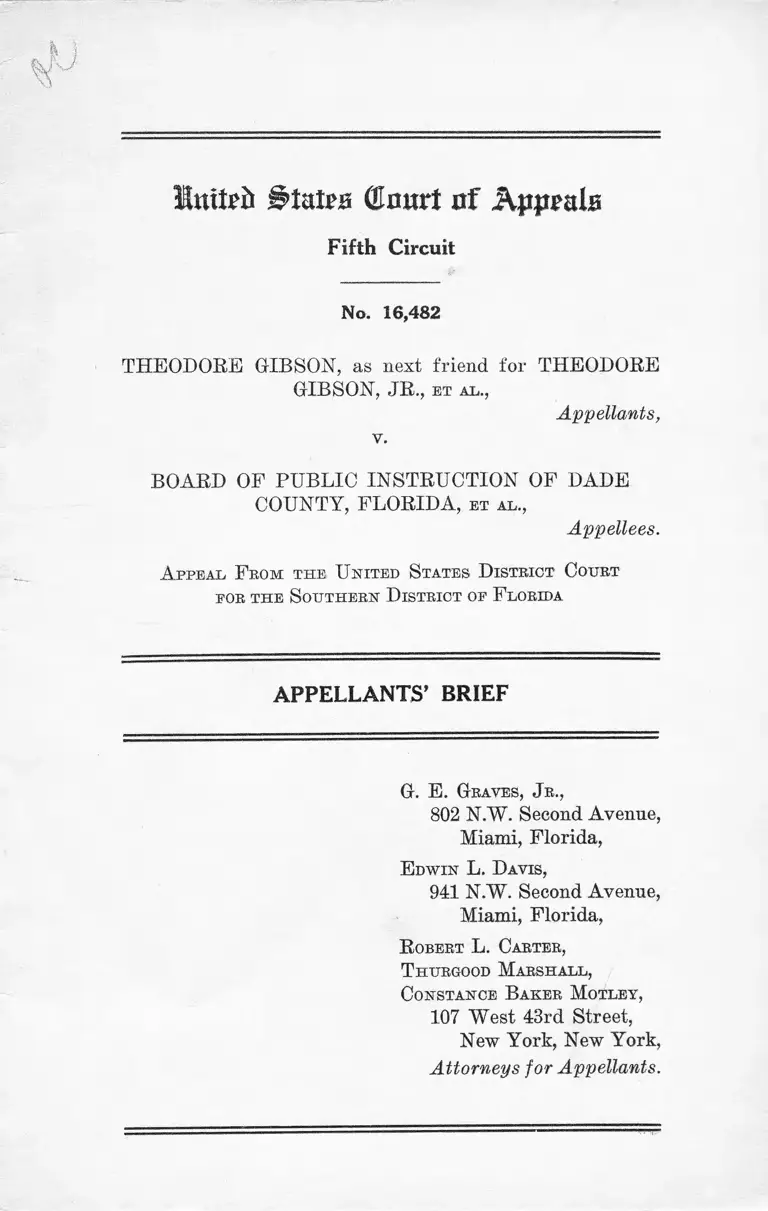

Gibson v. Dade County, FL Board of Public Instruction Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gibson v. Dade County, FL Board of Public Instruction Appellants' Brief, 1959. b8501b4d-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c818a5cd-961a-4385-a109-1cb5ea18a1db/gibson-v-dade-county-fl-board-of-public-instruction-appellants-brief. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Copied!

Imteib BtnUn (fnart of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

No. 16,482

THEODORE GIBSON, as next friend for THEODORE

GIBSON, JR., e t a l .,

Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF DADE

COUNTY, FLORIDA, e t a l .,

Appellees.

Appeal F rom the U nited States D istrict Court

eor the Southern District of F lorida

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

G. E . Graves, J r.,

802 N.W. Second Avenue,

Miami, Florida,

E dwin L. Davis,

941 N.W. Second Avenue,

Miami, Florida,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

Constance Baker Motley,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Appellants.

Imteii States dnart nf Appeals

Fifth Circuit

No. 16,482

• o

T heodore Gibson, as next friend for T heodore

Gibson, J r., et al.,

Appellants,

v.

B oard of P ublic I nstruction of Dade County,

F lorida, et al.,

Appellees.

o

A ppeal F rom the United States D istrict Court

for the Southern District of F lorida

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Florida dismiss

ing the appellants’ amended complaint, on the ground that

it fails to set forth a justiciable case or controversy upon

which the court could exercise its judicial power (E. 10-

13).

Appellants are infant Negro pupils residing in Dade

County, Florida, their parents and next friends who filed

the complaint below seeking a declaratory judgment that

Article 12, Section 12 of the Constitution of Florida and

Section 228.09, Florida Statutes Annotated, 1941, requiring

racial segregation in the state’s public schools, may not be

2

enforced by defendant school authorities of Dade County

(R. 5). An interlocutory and permanent injunction are also

sought to enjoin appellees from requiring the minor

appellants and all other Negroes of public school age to

attend racially segregated schools in Dade County (R.

5-6). Appellees moved to dismiss the amended complaint

on the ground, inter alia, that it fails to allege sufficient

ultimate facts to show the existence of a justiciable issue

between them and appellants or the class which they rep

resent (R. 8-9).

The court below granted the motion and dismissed the

complaint (R. 10). In its stated reasons for decision, the

court concluded it had no jurisdiction to hear or determine

the case in view of appellants’ failure to allege that they

had sought admission to and had been denied admission to

integrated schools by appellees (R. 12). It held that there

“ is presently no act of the defendants constituting any

deprivation of any of the plaintiffs’ rights before this

Court nor has there been any desegregation plan submitted

by the defendants for this Court’s consideration” (R. 13).

This ruling was made despite the fact that the complaint

specifically alleged that: (1) the public schools of Dade

County were presently being operated on a racially segre

gated basis; (2) appellants had filed a petition requesting

appellees to desegregate these schools and comply with the

law of the land; (3) appellees had refused to desegregate the

schools and had adopted a policy of continued segregation;

(4) each appellant was seeking admission to school with

out racial segregation; and (5) that the constitutional and

statutory provisions requiring segregation were being en

forced by appellees in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

3

Specification of Errors Relied Upon

1. The court below erred in dismissing the complaint on

the grounds that it failed to set forth a justiciable

case or controversy.

2. The court below erred in ruling that the absence

of an allegation in the complaint that the appellants

have sought admission to integrated schools and have

been denied admission by appellees, in violation of

appellants’ constitutional rights, divested the court

of the power to proceed further in the case.

3. The court below erred in ruling that the statement of

policy of appellees to continue to maintain racially

segregated schools did not vest the court with juris

diction to determine this cause.

4. The court below erred in ruling that there is pres

ently no act of appellees constituting any deprivation

of any of appellants ’ rights, and that it could not act

because no plan of desegregation had been submitted

by appellees for the court’s consideration.

ARGUMENT

The Complaint Sets Forth A Justiciable Case or

Controversy Upon Which A Federal Court Should

Exercise Its Judicial Power.

1. The complaint clearly and succinctly sets forth that

infant appellants, who by this action seek admission to the

public schools of Dade County, Florida, without racial seg

regation, are Negro citizens of the United States and the

State of Florida and satisfy all of the requirements for ad

mission to Dade County’s public schools (R. 3). The com

plaint also sets forth that appellees, the Board of Public

Instruction of Dade County, its superintendent and indi

vidual members, jointly maintain and supervise all of the

4

public schools of Dade County under a system which main

tains certain schools exclusively for the education of white

children and others for the education of colored children

only (R. 3).

In addition, it is alleged: that on September 7, 1955,

appellants petitioned appellee Board to abolish racial seg

regation in its schools as soon as practicable in conformity

with the second decision of the Supreme Court of the

United States in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

349 U. S. 294 (R. 3-4); that the Board neither desegregated

the schools nor took any steps towards the establishment

of an integrated school system; on the contrary, it adopted

a policy expressly committing the Board to continue to

operate, maintain and conduct the Dade County Schools

on a non-integrated basis until further notice, in accord

with the laws and Constitution of Florida requiring racial

segregation therein (R. 4); that the Board refused to de

segregate the schools operated and maintained by it as

soon as practicable (R. 5); and that constitutional and

statutory provisions requiring racial segregation were

being enforced despite the fact that they violate the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

(R. 5).

Such a complaint clearly presents an issue—the validity

of the racially segregated school system presently in opera

tion in Dade County—upon which a federal court can and

should act. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra.

“ If this issue does not present a justiciable controversy,

it is difficult to conceive of one.” Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, 138 F. Supp. 337, 340 (E. D. La. 1956), aff’d,

— F. 2d — (5th Cir. decided March 1, 1957).

Despite the foregoing allegations, the court below ruled

that since appellants nowhere alleged that they had ever

sought admission to integrated schools and had been de

nied admission to such schools by appellees, in violation

of plaintiffs’ constutional rights, it had nothing before it

to decide (R. 12). But such an allegation is not essential

to a statement of a valid cause of action in the circum

stances of this case. Appellants do not and cannot seek

specific assignment to particular schools. Rather, they

seek an end to appellees’ policy of racial segregation in

the public schools. Appellants cannot, as yet at any rate,

object to school assignment on any basis other than race.

Thus, this case presents the identical issue which was re

cently presented to this Court in the Bush case, supra,

wherein this Court stated:

Appellees were not seeking specific assignment to

particular schools. They, as Negro students, were

seeking an end to a local school board rule that re

quired segregation of all Negro students from all

white students. As patrons of the Orleans Parish

School system they are undoubtedly entitled to have

the district court pass on their right to seek relief.

Jackson v. Raw don (5 Cir.), 235 F. 2d 93, cert. den.

352 U. S. 925, and see School Board of the City of

Charlottesville v. Allen, supra.

Moreover, so long as assignments could be made

under the Louisiana constitution and statutes only

on a basis of separate schools for white and colored

children to remit each of these minor plaintiffs and

thousands of others similarly situated to thousands

of administrative hearings before the board for relief

that they contend the Supreme Court has held them

entitled to, would, as the trial judge said, “ be a vain

and useless gesture, unworthy of a court of equity,

* * * a travesty in which this court will not partici

pate.” See Adkins v. Newport News School Board,

(D. C. E. D. Va.), decided 1/11/57, 25 L. W. 2317.

Nor, we submit, is such an allegation as that deemed

necessary below to a statement of a good cause of action

under the Federal Civil Rights Statutes. This Court re

6

cently ruled in Heyward v. Public Housing Administration,

238 F. 2d 689 (5th Cir. 1956) that a cause of action is stated

under the Civil Eights Statutes, where it is claimed in effect

that Negroes are not permitted to make application for a

public facility limited by public officials to white persons

(at 689). As shown by the allegations of the complaint,

appellants’ claim here is that since the schools of Dade

County are and have been operated on a racially segregated

basis from the beginning pursuant to the constitution and

laws of the State of Florida, appellants are legally and

actually prohibited from seeking admission to white schools.

Or, to put it another way, appellants’ claim is that appel

lees’ refusal to comply with the Supreme Court’s decision

in the Broivn case, after having been requested to do so by

them on September 7, 1955, or to come forward with a

plan for desegregation of the Dade County Schools, vio

lates their constitutional right not to be required to at

tend a racially segregated school. That this claim pre

sents a valid cause of action finds support in the decided

cases: Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied, 352 IT. S. 925; Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, supra; School Board of City' of Charlottesville v.

Allen, 240' F. 2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956); cert, denied, 353 U. S. —,

1 L. ed. 2d 664; Whitmore v. Stillwell, 227 F. 2d 188 (5th

Cir. 1955); Evans v. Members of the State Board of Edu

cation, 145 F. Supp. 873 (D. Del. 1956).

In School Board of City of Charlottesville v. Allen,

supra, defendant school boards similarly claimed that the

plaintiffs were not entitled to relief “ because they

[had] not individually applied for admission to any par

ticular school and been denied admission.” In reply to

this the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled:

“ The answer is that in view of the announced policy of the

respective school boards any such application to a school

other than a segregated school maintained for colored peo

ple would have been futile; and equity does not require

7

the doing of a vain thing as a condition of relief” (at 63-

64).

Thus, the absence of a specific allegation, that appel

lants here sought admission to integrated schools and were

denied admission by appellees in violation of appellants7

constitutional rights, does not preclude the court below

from proceeding to a determination of the merits of this

cause.

2. The August 17, 1955, statement of policy is clear

and concise:

It is deemed by the Board that the best interest

of the pupils and the orderly and efficient adminis

tration of the school system can best be preserved if

the registration and attendance of pupils entering

school commencing the current school term remains

unchanged. Therefore, the Superintendent, princi

pals and all other personnel concerned are herewith

advised that until further notice the free public

school system of Dade County will continue to be

operated, maintained and conducted on a noninte-

grated basis.

This is an unquestionable and conclusive refusal on de

fendants’ part to abide by the decision in the School Seg

regation Cases. Cf. Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board,

supra. And, despite the September 7 petition, the Board

refused to depart from its already decided policy of Au

gust 17. If the justiciable issue in school desegregation

cases is whether a school board may operate schools under

its jurisdiction on a racially segregated basis, then such

issue is patently presented by a complaint which alleges that

a petition has been filed with the school board requesting de

segregation and the board had adopted a policy statement

declaring that “ * * * until further notice the free public

school system of Dade County will continue to be operated,

maintained and conducted on a non-integrated basis” (R.

8

4), and takes no action in respect to the aforementioned

petition filed. Especially is this true when such a statement

of policy is considered, upon a motion to dismiss, in the

light of other facts in this complaint, which include an alle

gation that the constitutional and statutory provisions of

the state requiring racial segregation in the public schools

are being enforced by appellees (E. 5).

in Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, supra, 341;

School Board of City of Charlottesville v. Allen and County

School Board of Arlington County v. Thompson, supra, 63-

64; and in Jackson v. Bawdon, supra, 95, the defendant

boards made similar announcements," "and the courts re

garded them as sufficient denials of appellants’ rights to

present a justiciable issue.

3. The court below ruled that whether appellees will

follow the decision of the United States Supreme Court

in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

supra, cannot yet be determined (E. 12). It expressed the

view that it believes that these appellees have not lightly

taken their required oath to uphold the Constitution of the

United States (E. 12). This was plain error, in view of

the fact that the court was making such a ruling upon a

motion to dismiss, for the purposes of which the allega

tions of the complaint are deemed admitted. This Court

very recently held in Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent

School District, 241 F. 2d 230 (5th Cir. 1957) that “ an

issue depending largely on the good faith of the defendants

can be better determined by the district court after a full

and fair hearing” (at 234). There has been no hearing

whatsoever in this case, and the complaint certainly raises

a question as to the good faith of these appellees.

Finally, the court below, in ruling that there was no act

of appellees before it which constituted a deprivation of ap

pellants ’ rights, apparently places reliance on the fact

that appellees had not submitted any plan of desegregation

to the court for its consideration (E. 13). Cf. Bell v.

9

Hippy, 133 F. Supp. 811 (N. D. Tex. Dallas Div.). This

was error for the reason that defendants could hardly

submit such a plan upon a motion to dismiss. Avery v.

Wichita Falls Independent School District, supra. The

court below could consider such a plan after declaring the

right of appellants to be admitted to schools without dis

crimination because of race or color, Whitmore v. Stillwell,

supra, only in connection wtih the exercise of its discretion

to grant or withhold an injunction, pending execution of the

plan. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra;

Jackson v. Rawdon, supra; Avery v. Wichita Falls Inde

pendent School District, supra.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the

court below is erroneous and should be reversed by

this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

Gr. E . Graves, J r.,

802 N.W. Second Avenue,

Miami, Florida,

E dwin L. Davis,

941 N.W. Second Avenue,

Miami, Florida,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

Constance Baker Motley,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Appellants.

S upreme P rinting Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, B E ekman 3-2320