Davis v. Prince Edward County, VA School Board Brief for Appellees in Reply to Supplemental Brief for the United States on Reargument

Public Court Documents

December 7, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Prince Edward County, VA School Board Brief for Appellees in Reply to Supplemental Brief for the United States on Reargument, 1953. 5f27753a-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c87651c6-7aed-4f21-bda3-aaf049f1bb57/davis-v-prince-edward-county-va-school-board-brief-for-appellees-in-reply-to-supplemental-brief-for-the-united-states-on-reargument. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

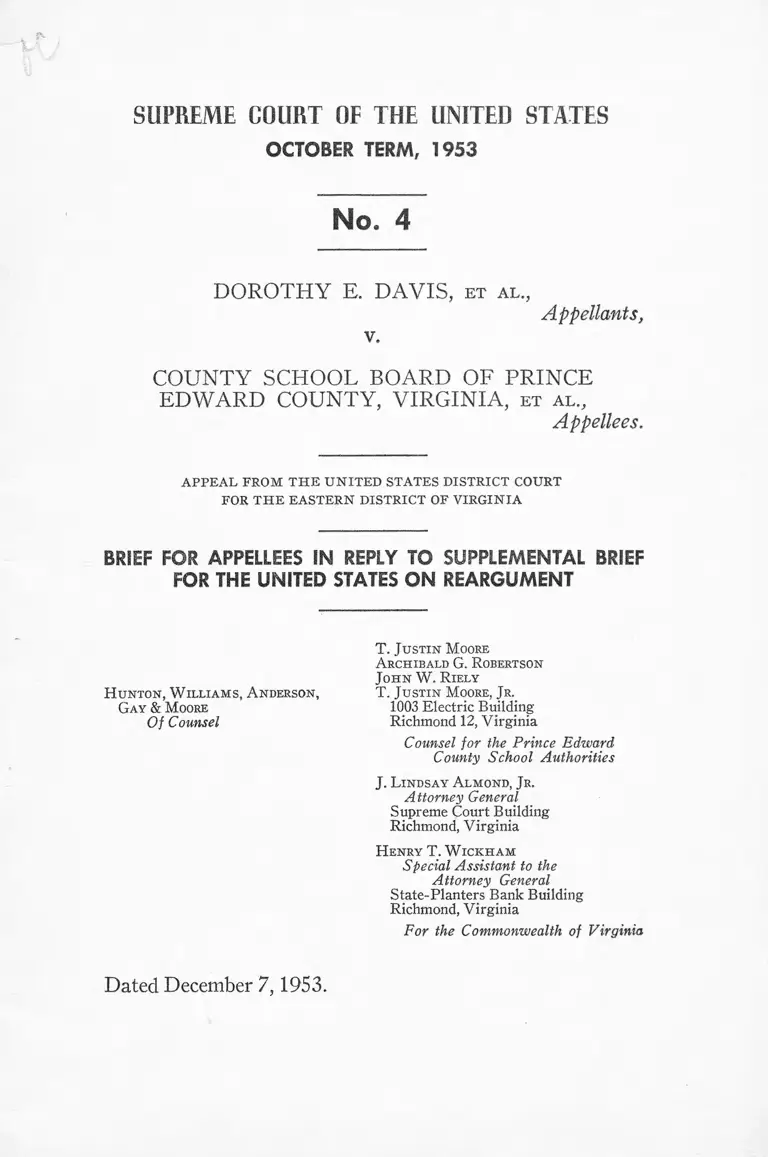

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1953

No. 4

D O R O TH Y E. DAVIS, e t a l .,

v.

Appellants,

COU N TY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE

ED W A R D COUNTY, VIRG IN IA, e t a l .,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES IN REPLY TO SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

FOR THE UNITED STATES ON REARGUMENT

H unton, W illiams, A nderson,

Gay & M oore

Of Counsel

T. Justin M oore

A rchibald G. R obertson

John W . R iely

T. Justin M oore, Jr.

1003 Electric Building

Richmond 12, Virginia

Counsel for the Prince Edward

County School Authorities

J. L indsay A lmond, Jr.

Attorney General

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia

H enry T. W ick ham

Special Assistant to the

Attorney General

State-Planters Bank Building

Richmond, Virginia

For the Commonwealth of Virginia

Dated December 7,1953

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I. Preliminary Statement ........................................................ 1

II. T he Congressional H isto ry ............................................... 2

III. T he State H istory .................................................................... 12

IV. T he Judicial Power .................................................................. 16

V. Conclusion ................................................................................ 21

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Commonwealth v. Davis, 10 Weekly Notes 156 (1881) .................. 16

Cory v. Carter, 48 Ind. 327 (1874) ....................... _........................... 16

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1927) ........................................... 18

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) ....... 17, 18

People ex rel. Dietz v. Easton, 13 Abb. Prac. (N . S.) 159 (1872).. 16

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896) ................................ 18, 20

Schwegmann Brothers v. Calvert Distillers Corp., 341 U. S. 384

(1951) .............................................................................................. 7

State ex rel. Games v. McCann, 21 Ohio State 198 (1871) ........... 16

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) ........................................... 19

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36 (1874) ..................................................... 16

Other Authorities

Page

Statutes at Large:

12 Stat. 394 (1862) .................................................................... 10

12 Stat. 407 (1862) ...................................................................... 10

12 Stat. 537 (1862) ........................................................................ 10

13 Stat. 187 (1864) ............................................... ........................ 10

14 Stat. 216 (1866) ...................................................................... 11

14 Stat. 342 (1866) ...................................................................... 11

Ga. Laws (1870) 57 .............................................................................. 14

Va. Acts (1869-70 ) 413 ................................... .................................... 14

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1 8 6 6 )....... 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1868) .................... ................ 11

Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1869) ....................................... 11

Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1872) ................................ 5, 20

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

I.

At the invitation of the Court, the Attorney General of

the United States has submitted a brief which, in general,

opposes the position taken by the Appellees in this case. W e

do not propose a detailed answer to his contentions, for time

does not permit. But we do propose to comment generally on

his more important conclusions for our study has convinced

us o f their error.

At the beginning, we dispose of his arguments as to the

fourth and fifth questions submitted by the Court, which,

in our view, are subsidiary to the main issue. With his pro

posals as to these matters, we are in substantial agreement.

Only as to his suggestion that amalgamation be accomplished

within a single year (Brief, p. 186) are we in substantial

disagreement. The Court has in the records before it now no

evidence as to the problems to be faced if segregation is to

be abolished; no one knows the extent of these problems or

the time that may be required for their solution. It seems to

us an arbitrary suggestion that the Court now fix a time

limit when it cannot have any real conception as to the ade

quacy or inadequacy of the limit so fixed. W e repeat our

view that the time is a matter for determination by the court

below in the light of the evidence to be presented to it if the

case be remanded. That court will then be able to require

the best practical solution in the light of the facts.

But the important issue is the main question: whether

segregated schools of themselves offend the Fourteenth

Amendment. In the framework of this case, that question

has three facets: the question of Congressional intent; the

question of the intent of the States; and the question of the

judicial power. To these three points we turn in the order

given.

2

THE CONGRESSIONAL HISTORY

It cannot be denied that the anti-slavery movement had a

broad humanitarian base; at the same time, it cannot be

proved that one of its aims was the abolition of segregation

by race in the public schools. The statements made by aboli

tionist leaders before the Civil W ar were all addressed to

the abolition of slavery. Statements made by radical leaders

in the 1870’s, when school segregation was an issue of Con

gressional debate, are not reliable as to their opinions in the

1850’s (Brief, pp. 12-13). Generalizations have no bearing

on the question asked by the Court; that is a question as to a

specific issue which merits and can be given a specific answer.

W e come, then, to the first session of the 39th Congress.

That was the session that passed the First Supplemental

Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

W e agree with the Attorney General that they are important

as a “ relevant part of the background of the Fourteenth

Amendment” (Brief, p. 22). W e further agree as to the

reason for their relevance; the facts are, as the Attorney

General so well states, that “ the rights intended to be secured

to Negroes by these measures were the same as those subse

quently embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment. . . .”

(Brief, pp. 21-2) That is also our concept; the two bills and

the Amendment covered the same ground and there is no

substantial evidence to support the claim of the Appellants

that the Amendment is o f broader reach (Appellants’ Brief,

P- H 8).

But after that determination we differ with the brief for

the United States. Let us take first the conclusion there

shown as to the two bills. The Attorney General says:

“ The debates on these bills show that some legislators,

on both the majority and minority sides, expressed the

II.

3

view that this principle o f equality under law would,

if enforced, destroy racial segregation in state schools.”

(Brief, p. 32)

W e assume that the Attorney General speaks of separate

equal State schools. W e disagree with this conclusion.

To support this conclusion, the Attorney General quotes

statements by Representative Dawson of Pennsylvania as

to the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and Senator Cowan of Penn

sylvania and Representatives Kerr of Indiana, Rogers of

New Jersey and Delano of Ohio as to the Civil Rights Act.

W e shall take them up one by one.

Representative Dawson voted against the Freedmen’s

Bureau Bill.1 He was, as the Attorney General says, not

speaking of the meaning of the Bill but of the general policy

of the radicals; he did not say what that Bill would do but

what he thought the radicals wanted to do. He cannot be

counted as one who said that the Bill would abolish segre

gated schools.

Senator Cowan of Pennsylvania was a strong opponent

of the Civil Rights Act and voted against its passage.2 He

later modified radically the views that he expressed earlier

in the debate which are quoted by the Attorney General

(Brief, p. 27). He followed Senator Trumbull’s interpreta

tion that the Act conferred only

“ . . . the rights which are here enumerated. . . ,” 3

He cannot be taken to have thought that the Act abolished

school segregation.

^ o n g . Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866) 688.

2 Id. at p. 607. He also voted to uphold the President’s veto. Id. at

p. 1809.

2 Id. atp. 1781.

4

Representative Kerr of Indiana voted against the Act.4

As his remarks quoted by the Attorney General (Brief, pp.

28-9) make clear, he did not talk about a situation where

separate schools were provided for both races; he limited his

remarks to the case where schools were provided for the

white and not for the Negro. His views do not bear on our

issue.

Representative Rogers voted against the Act.5 His views

both as to the Act and as to the Fourteenth Amendment and

the school question were unique as we have already shown

(Appellees’ Brief, pp. 93, 106-7).

Representative Delano, alone of those here discussed,

voted for the Act.6 But as is again evident from the quota

tion in the Brief for the United States (Brief, pp. 30-1), he,

like Mr. Kerr, was speaking of the situation where the

Negro was excluded completely from the schools. He can

not be taken to have meant that the Act would strike down

separate schools for Negroes.

Where, then, are those on the majority side who believed

that these statutes would outlaw school segregation as we

know it ? There were none. But there were those on the ma

jority side who considered that these statutes would not

abolish school segregation. These, the Attorney General

either minimizes or ignores.

First, there was Senator Trumbull of Illinois, patron of

the Civil Rights Act and Chairman of the Senate Judiciary

Committee. W e quote his statement as to the Act again:

“ The first section of the bill defines what I under

stand to be civil rights: the right to make and enforce

4 Id. at p. 1367. He was recorded as not voting on the question of

sustaining or overruling the veto. Id. at p. 1861.

5 Id. at p. 1367. He voted to uphold the President’s veto. Id. at

p. 1861.

6 Id. at p. 1367. He also voted to override the veto. Id. at p. 1861.

5

contracts, to sue and be sued, and to give evidence, to

inherit, purchase, sell, lease, hold, and convey real and

personal property.

* * *

“This bill has nothing to do with the political rights

or status of parties. It is confined exclusively to their

civil rights, such rights as should appertain to every

free man.” 7

This we may note is the same Senator Trumbull who, in

1872, said:

“ The right to go to school is not a civil right and

never was.” 8

In the House, there was Representative Wilson of Iowa,

Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and in charge

of the progress o f the Act through the House. He made his

position unmistakable:

“ Do [the provisions of the bill] mean that in all things

civil, social, political, all citizens, without distinction of

race or color, shall be equal ? By no means can they be

so construed. . . . Nor do they mean that . . . their chil

dren shall attend the same schools. These are not civil

rights or immunities.” 9

sjf sfc

“ He knows, as every man knows, that this Bill refers

to those rights which belong to men as citizens of the

United States and none other ; and when he talks of

setting aside the school laws and jury laws and fran

chise laws of the States by the Bill now under considera

tion, he steps beyond what he must know to be the rule

of construction which must apply here, and as the result

1 Id. at p. 475.

8 Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1872) 3189.

8 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866) 1117.

6

of which this Bill can only relate to matters within the

control of Congress.” 10

These statements cannot be minimized as the Attorney

General attempts to do (Brief, p. 28). They are clear and

directly on the point.

In accordance with the rule that this Court has established,

we take these statements of the responsible Committee Chair

men as authoritative guides to the meaning of this legisla

tion. The Civil Rights Act was not intended to abolish seg

regation in the schools.

Since the Attorney General and all others except the Ap

pellants agree that the only purpose of the Fourteenth

Amendment was to cover the same ground as the Civil

Rights Act, our inquiry is nearly at an end. But we cannot

stop here for the Attorney General continues by drawing

conclusions which are quite at variance with what should

have been his premises.

He concludes that

“ The civil rights legislation enacted by the 39th Con

gress was designed to strike down distinctions based

on race or color.” (Brief, p. 113)

If he means some distinctions, we agree; if he means all

distinctions, we cannot agree for the evidence is to the con

trary. He continues by stating that, when the minority ex

pressed the view that the Civil Rights Act would strike down

segregation in the schools,

“ This view was not disputed by the majority.”

(Brief p. 115)

Again we cannot agree for Trumbull and Wilson disputed

it explicitly. W e hasten to add that, even if the statement

10 Id. at p. 1294.

7

were supported by the record, uncontradicted statements

of opponents are no guide to legislative interpretation.11

But our disagreement has still further to go. The Attorney

General implies the opposite of his explicit statement that

the Amendment and the Civil Rights Act cover the same

ground when he asserts in connection with the Amendment

that it was not

“ . . . necessary or appropriate to catalog exhaustively

the specific application of its general principle.”

And his general principle is, we are told, that the Amend

ment

“ . . . would prohibit all legislation by the states drawn

on the basis of race and color.” (Brief, p. 114)

Let us examine this general principle. In 1866, the Con

stitution contained no limitation on the power of the States

to determine to whom the right of suffrage could be given.

Many o f the States, north and south, prohibited the Negro

from voting by legislation. This was certainly legislation

“ drawn on the basis of race and color.” Was the Fourteenth

Amendment designed to abolish this ?

Senator Howard of Michigan, a member of the Joint

Committee on Reconstruction and the senator in charge of

the Amendment in the Senate, is our guide on this question.

He said:

“ But sir, the first section of the proposed amendment

does not give to either of these classes the right of

voting.” 12

11Schweamann Brothers v. Calvert Distillers Corp., 341 U. S. 384

(1951).

12 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866) 2765.

8

He said the same thing at a later date:

“ The Committee were of opinion that the States are

not yet prepared to sanction so fundamental a change

as would be the concession of the right of suffrage to

the colored race.” 13

Why was not the right of suffrage included ? Because, said

Senator Howard, it was

“ • . . not regarded as one of those fundamental rights

lying at the basis o f all society and without which a

people cannot exist except as slaves, subject to a despot

ism.” 14

The Attorney General cannot therefore be correct in his

conclusion that the Amendment proscribed “all legislation

. . . drawn on the basis of race and color.” Here is one field—

a right that we now regard as most fundamental in our

democracy— that the Amendment was designed not to cover.

That was covered by a later and different amendment to the

Constitution. And Senator Trumbull, patron of the Civil

Rights Act, made it equally clear that the Act had no effect

on statutes prohibiting miscegenation.15 In sum, there was

general agreement that the scope of operation of the Four

teenth Amendment was limited to “ fundamental rights,” as

Senator Howard, its chief Senate proponent, made unequivo

cally clear. Most o f these rights were, contrary to the con

clusion of the Attorney General (Brief, p. 114), catalogued

13 Id. at p. 2896. Senator Poland of Vermont, another radical leader,

spoke in the same vein. Id. at p. 2961.

14 Id. at p. 2765.

15 Id. at p. 600.

9

by Thaddeus Stevens.16 They were also catalogued by Sena

tor Howard.17 In neither catalogue are schools included.

Despite his agreement twice stated (Brief, pp. 21-2, 109)

that the Amendment was designed to cover only the same

ground as that covered by the Civil Rights Act, the Attorney

General implies that it may have gone further. He refers to

Stevens’ statement (Brief, p. 44). That statement, given in

full in the Appellees’ Brief, is repeated here:

“ Some answer, ‘your civil rights bill secures the same

things.’ That is partly true, but a law is repealable by

a majority. And I need hardly say that the first time

that the South with their copperhead allies obtain the

command of Congress it will be repealed. . . .” 18

Here Stevens’ meaning is clear: the two covered the same

ground ; the only difference lay in that the Amendment could

not be repealed. And Stevens, like Howard, made it clear

that the Amendment did not go all the w ay:

“ It falls far short of my wishes. . . ,” 19

Stevens, like Howard,20 Garfield,21 Rogers,22 Poland,23 Hen

derson24 and many others, put it beyond doubt that the

Amendment and the Civil Rights Act had the same applica

tion. This is the accepted interpretation.

leId. at p. 2459; Appellees’ Brief, p. 105.

17 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866) 2765; Appellees’ Brief,

pp. 108-10.

18 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866) 2459.

™Ibid.

20 Id. at p. 2896.

21 Id. at p. 2462.

22 Id. at p. 2538.

23 Id. at p. 2961.

24 Id. at p. 3031.

10

The Attorney General makes another point. He says:

“ It is noteworthy that one of the majority spokesmen

. . . illustrated the racial discriminations which the

Amendment would reach by reference to a state law

•discriminating against Negroes in public schools.”

(Brief, p. 114)

That is a true statement. But it tends to confuse the issue.

The spokesman was Senator Howe of Wisconsin. His re

marks are quoted by the Attorney General (Brief, p. 54).

He complained of a Florida statute that taxed both whites

and Negroes to support the white schools and then taxed the

Negroes again to support the Negro schools.25 There seems

to us no question as to the inequality of this statute, but it

seems to us to have little relevance to the constitutionality

o f segregated schools. The vice of the statute is obvious; the

remarks, in this connection, are hardly “noteworthy.”

The Attorney General passes then to the history of school

legislation in the District of Columbia (Brief, pp. 69-72).

This history, he asserts, is of small significance ; Congress

was almost unconscious when it acted to establish and to

retain segregated schools in the 1860’s. The actions of

Congress, he says, are unreliable; it is only the words that

give enlightenment. Words, in his view, speak louder than

actions. Merely to state this thesis is to refute it. When

Congress first established schools for the District of Co

lumbia in 1862, a conscious choice was required; schools

should either be segregated or mixed. Congress chose the

segregated course.26 It reiterated its decision in 1864.27 The

39th Congress that proposed the Fourteenth Amendment

25 Id. at App. p. 219.

2612 Stat. 394, 407, 537 (1862).

2713 Stat. 187 (1864).

11

enacted, almost simultaneously with its proposal, two stat

utes relating to and retaining the District’s segregated

schools.28 Can Congress have been unconscious o f the segre

gation existing pursuant to its will under its nose? That

cannot be true. Appellants have told us in some detail how

Congress outlawed segregation in District transportation in

1865 (Appellants’ Brief, pp. 77-78). That was just one

year before the proposal o f the Amendment. But that is

not the end of the story. In 1868 and 1869, Congress acted

again; a District school law was passed which did not abolish

segregation.29 This must have caused some thought for it

was vetoed by the President.30 Was Congress asleep for

this whole period? It was certainly not asleep in 1871 and

1872 when it debated at length a bill to amalgamate the

District schools (Appellees’ Brief, pp. 130-4). No bill for

this purpose could achieve passage.

W e consider the record from the District convincing

evidence of Congressional intention. It cannot be summarily

dismissed as inconsequential. It is an accurate reflection o f

the temper of the Congress that proposed the Fourteenth

Amendment.

As to the legislation that was proposed in the 1870’s, the

Attorney General presents no full discussion (Brief, pp.

76-86). He quotes Sumner and Butler and their generali

zations on equality. But he misses the point. The point is

that no one ever said that the Fourteenth Amendment abol

ished segregated schools; no one ever suggested that legis

lation was unnecessary because the Amendment had already

done the job. In sum, all agreed that, in order to abolish

segregated schools, additional legislation was required. The

2814 Stat. 216, 342 (1866).

29 Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1868) 3900; Cong. Globe,

40th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1869) 919.

30 Id. at p. 1164.

12

argument arose over the power of Congress to legislate and

the expediency of the legislation. These were, to a large

degree, the same men who proposed the Amendment. Their

views confirm its meaning.

In conclusion, we cannot agree with the Attorney General

that, in the legislative history, there is

“ . . . no conclusive evidence of a specific understanding

as to the effect of the Fourteenth Amendment on school

segregation. . . .” (Brief, p. 125)

W e believe that there is substantial affirmative evidence that

the Amendment was understood not to affect school segre

gation. W e know from Senator Trumbull and Representa

tive Wilson that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was not to

affect school segregation. W e know from many, including

the Attorney General, that the Amendment was designed

to cover only the rights covered by the Civil Rights Act.

W e know that all through this period Congress fostered

segregated schools in the District o f Columbia. W e know

that the later civil rights history contains no assertion that

the Amendment of its own force abolished school segrega

tion.

In our view, the evidence is convincing. Congress did not

intend to abolish segregated schools.

III.

THE STATE H ISTORY

The Attorney General makes no thorough review of the

history as it may be derived from the records of the several

States.31 He draws only three conclusions that require com

ment. And the comment may be quite brief.

31 It may be that such a review is made in the Appendix to his brief,

but, at the time that this brief went to the printer, his Appendix has

been promised (pp. 4, n.3 and 90, n.93) but not produced.

13

The Attorney General despairs o f reaching a decision

on the State question. That is, he says, because there is no

evidence of

. . an awareness that the Fourteenth Amendment

might be relevant in determining the basis on which

public, education was furnished.” (Brief, p. 99)

W e agree to some extent with this point. And we consider

it obvious that it is just the point. To show why is simple.

He cannot mean that there was no general awareness of

the Fourteenth Amendment and of its purpose. Certainly

the Amendment created an issue of paramount importance

and interest from 1866 until 1870.

By the same token, he cannot mean that there was no

general awareness of schools, and particularly segregated

schools. The nation was in educational ferment in the period

just following the Civil War. This was particularly true in

the southern States where systems of public schools were

universally established for the first time.

He means that no one had any awareness that the Four

teenth Amendment had the effect of abolishing segregated

schools. From this he can draw no conclusion. But it seems

to us that the conclusion is obvious. If the framers of the

Fourteenth Amendment in Congress and the legislators

that voted to ratify it had intended that it should abolish

segregation in the public schools, there would have been

and have been evidence of the awareness which the Attor

ney General has sought and cannot find. W e take that lack

of evidence to be the best evidence that the legislators did

not intend to put segregated schools beyond the constitu

tional pale when they voted to ratify the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

But from that basic misconception, the Attorney General

moves on to prove too much. He asserts that legislation

14

(contemporaneous with ratification) to establish segregated

schools has no significance in establishing the climate of

legislative opinion because there is no evidence of awareness.

He asserts that 5 different hypotheses may be established

from that apparently unrelated evidence (Brief, pp. 105-6).

O f these he asserts as most likely the hypothesis that some

but not much education was required for both races if any

were offered to either (Brief, p. 108). He asserts as least

likely that the legislators chose the separate but equal stand

ard (Brief, p. 106).

But it seems to us that there is some evidence of aware

ness and evidence of awareness of the separate but equal

standard. W e have not examined all the school statutes of

the reconstruction period; time has not permitted. But here

are two examples.

The Virginia statute of 1870 is in almost the same words

as the statute of today. It stated:

“ . . . provided, that white and colored persons shall not

be taught in the same school, but in separate schools,

under the same general regulations as to management,

usefulness, and efficiency. . . ,” 32

The Georgia statute of 1870 provided:

“ Section 32. And be it further enacted, that it shall

be the duty o f the trustees, in their respective districts,

to make all necessary arrangements for the instruction

of the white and colored youth of the district in sepa

rate schools. They shall provide the same facilities for

each, both as regards school-houses and fixtures, and

the attainments and abilities, length of term-time, etc.;

but the children of the white and colored races shall not

be taught together in any subdistrict of the State.” 33

32 Va. Acts (1869-70) 413.

33 Ga. Laws (1870) 57.

15

Can these statutes have more than one interpretation?

W e think not. They wrote the separate but equal doctrine

into the public school laws of Virginia and Georgia. And

these statutes were both enacted by legislatures that ratified

the Fourteenth Amendment.

W e believe this to be substantial evidence that the State

legislatures had an awareness of their obligation to provide

equal schools. Many of them may not have formalized the

constitutional standard of separate but equal into their stat

utes but at least some recognized the standard and enacted

it into law. W e do not believe that the evidence supports

the conclusion that the separate but equal doctrine was a

thing unknown.

That schools may not have been in fact at once equal is

no secret. But local prejudices cannot be overlooked; those

who paid most of the taxes were reluctant to see much of

their money go for the exclusive benefit o f those that paid

few of the taxes. But that factor has no relevance to legis

lative intent or understanding.

Finally, the Attorney General concludes that the early

State decisions fail to

“ . . . evidence any general and definite contemporaneous

judicial construction of the Amendment as applied to

school segregation.” (Brief, p. 104)

W e may, with him, disregard those State cases that depend

entirely on State law. But it is difficult for us to agree that

no conclusion may be drawn from the other cases cited by

the Attorney General. The decisions are almost all on our

side. The Attorney General cites, as do we, cases from the

highest courts of California, Indiana, New York and Ohio

holding that segregated schools did not offend the Four

teenth Amendment. His only authority to the contrary is a

16

case from “ a lower court in Pennsylvania” so obscurely re

ported that it had escaped our notice (Brief, pp. 103-4).34 His

conclusion, derived from this balance of authority, seems

erroneous, no matter how partisan the observer may be.

W e conclude that the lack of direct evidence as to the

relationship of the Amendment and the schools is firm evi

dence that the legislators neither contemplated nor under

stood that the Amendment required the end of school segre

gation. W e conclude further that there is affirmative evi

dence from legislatures that ratified the Amendment that

equality in education was required. The early State decisions

confirm these conclusions.

W e invite the Attorney General here, as in the case of the

record from Congress, to climb down from his historical

fence.

IV .

THE JUDICIAL POWER

Counsel in these cases have shown a marked disagreement

as to the investigation desired by the Court in response to its

question as to the judicial power. The Attorney General,

although he touches upon occasion on the field that we at

tempted to explore, has for the most part taken off in an

other direction.

He states first that a case or controversy exists before the

Court; we are in agreement (Brief, pp. 133-5). He states

last that the cases involving “political questions” are not in

point (Brief, pp. 149-51). With that view, we are less in

34Compare Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36 (1874), Cory v. Carter, 48

Ind. 327 (1874), People ex rel. Dietz v. Easton, 13 Abb. Prac. (N. S.)

159 (1872), and State ex rel. Games v. McCann, 21 Ohio State 198

(1871), with Commonwealth v. Davis, 10 Weekly Notes 156 (Court

of Common Pleas, Crawford County, Pennsylvania, 1881). The judge

there cited no relevant authority.

17

agreement. It is true that no decision in this case will inter

fere with the conduct of foreign affairs by the executive

branch of the government. But that is a superficial analysis.

Many of the same considerations are applicable (Appellees’

Brief, pp. 37-40). The Court is not dealing here, as it was

in the graduate school cases, with a dozen or so institutions

to which a mere handful of applicants of color sought ad

mission.35 The Court is, in the last though not the

first analysis, dealing with thousands of local school districts

and schools. Is each to be the subject of litigation in the

District Courts ? Are those courts to manage the local school

systems for a time? That merely points up that this Court,

as in the political question cases, is dealing with a problem

normally outside the scope of the judicial machinery. The

shoe does not fit the foot. That fact is, of itself, evidence

that the proper place for solution of the problem is in the

legislature.

W e do not quarrel with the Attorney General when he

says that the Fourteenth Amendment is self-executing with

out further Congressional implementation (Brief, pp. 135-

8). Indeed, we agree. W e have expressed our view on the

limits of the power of Congress (Appellees’ Brief, pp. 39-

41). Nor do we complain of his quotations from early de

cisions of this Court which declare that the purpose of the

Fourteenth Amendment was to protect the Negro in his

fundamental rights (Brief, pp. 118-25). Those decisions ac

cord exactly with what was said in the 39th Congress.36

But those decisions do not declare that those fundamental

rights included the right to go to a mixed school or that the

85 There are now only 7 Negroes in the graduate schools of the Uni

versity of Virginia, none in those of the University of South Carolina.

36 See the words of Senator Howard quoted above at page 8.

18

separate but equal doctrine offends the Amendment. When

that doctrine first came before this Court, it was upheld.37

The Attorney General injects a new idea in his argument

about the recent school cases (Brief, pp. 143-9). He begins

with a statement that the Fourteenth Amendment requires

the maintenance of public schools (Brief, p. 143). This is

a novel thought, not shared by President Grant38 and un

supported by any decision of this Court. He then seems to

go on to say that, prior to the Gaines case,39 this Court said

simply that education was a “ privilege” and not a “ right”

and that a State could grant or deny “privileges” unequally

at will and with impunity. Then, he asserts, in the Gaines

case for the first time the Court required equality of “privi

lege.”

W e assume that the Attorney General would make the

same argument as to transportation. But there his argu

ment can hardly be valid. This Court was careful to speak

of equality when the matter was first before it. In Plessy

v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 543 (1896), this Court said:

“ A statute which implies merely a legal distinction

between the white and colored races . . . has no tendency

to destroy the legal equality of the two races. . . .”

Would the result in Plessy v. Ferguson40 have been the same

if the Louisiana statute had required the railroad to refuse

transportation to the Negro? That can hardly be imagined.

In Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1927), there was no

assertion of factual inequality. That was not an issue. The

Supreme Court of Mississippi had found that the school

system there required schools for both races

37 Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896).

38 Brief for Appellees, p. 146.

39Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938)

40 The case came up on a writ of prohibition. Factual inequality was

neither alleged nor in issue.

19

“ . each having- the same curriculum, and each hav

ing- the same number of months of school term. . . ”

(275 U. S. at p. 84)

This Court apparently took that as an assertion of equality

unchallenged by the Appellant. Factual inequality was for

the first time at issue in the Gaines case, and this Court,

having found factual inequality, was quick to apply the well

established rule that, absent equality, separation offends the

Constitution. That case and its successors did not give edu

cation a constitutional sanction which it had not previously

enjoyed; the Court there merely applied the established doc

trine, a doctrine that it refused to re-examine even though

asked to do so.41

W e now approach the Attorney General’s final argument

on the Fourteenth Amendment. First, we are told that al

though the background o f a constitutional provision is of

assistance in determining its meaning, there is no necessity

to find specific evidence that the framers intended that spe

cific meaning (Brief, p. 126). But the question rather is

where, as here, the intent and meaning of the framers is

unmistakable (this Amendment shall not be construed to

abolish segregated schools), may this Court adopt the oppo

site interpretation (the Amendment is hereby construed to

abolish segregated schools). The Attorney General, deny

ing the premise, provides no assistance in reaching the prop

er answer. Again, we repeat our view that such an interpre

tation is an unwarranted extension o f the judicial power.

But, for the purpose of argument, we will assume the

erroneous premise of the Attorney General that the mean

ing o f the framers as to the effect o f the Amendment on

school segregation is indeterminate. Then, he says, whether

segregated schools met the constitutional test o f the Nine

« Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629,636 ( 19S0).

20

teenth Century is irrelevant, for conditions have so changed

that a statute establishing them is today an arbitrary fiat

(Brief, pp. 142-3). And the test to be applied is a simple

one:

“ But reasonableness is not measured in the abstract;

the standard of reasonableness is found in the pro

visions and policy of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

(Brief, pp. 138-9)

W e do not agree with his statement of the standard for

the standard that he suggests cannot possibly be applied.

The test, as this Court has told us, is whether the classifi

cation is reasonable in the light o f the particular facts. The

Amendment provides the standard of reasonableness; the

standard cannot lead us directly back to the Amendment.

Reasonableness can only be determined from the facts; un

reasonableness must appear from the facts.

If we are to look for changed conditions and evidence of

unreasonableness, we turn first to the record. There we find

it urged by witnesses for the Appellants that segregated

schools constitute “an official insult” (R. 195) and are evi

dence of “prejudice” (R. 210). In 1872, Charles Sumner

spoke of

“ . . . the prejudice of color which pursues its victim

in the long pilgrimage from the cradle to the grave.

J ) 4 2

He spoke again:

“ The separate school has for its badge inequality.” 42 43

42 Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1872) 384.

*sId. at p. 434. These same arguments were presented and disre

garded in Plessy v. Ferguson. See Appellees’ Brief, pp. 48-9.

21

His arguments are identical with those of record here. The

record provides no evidence of changed conditions.

O f course, conditions have changed greatly since 1870.

W e cannot overlook the jet plane and the atomic cannon.

Yet the record is bare of evidence of the extent of the perti

nent changes in Prince Edward County, Virginia. And the

fact o f change is irrelevant unless the change has made seg

regation in the schools beyond the bounds of reason.

The Attorney General has remarked upon the record and

the findings in the Kansas case (Brief, p. 149). He has not

mentioned the record and the findings in this case. He will

find little to comfort him there. The evidence is that in the

Prince Edward County high schools segregated education is

best for the pupils o f both races. The findings based on that

evidence are clear;

“ W e have found no hurt or harm to either race. That

ends our inquiry.” (R. 621-2)

In these circumstances, are segregated high schools in

Prince Edward County, Virginia, beyond reason? W e sub

mit that a negative answer is required. As a result, the

Amendment is not offended. That should end the inquiry

for this Court as it did for the court below.

V.

CONCLUSION

In this short brief we have attempted to make clear our

chief points of disagreement with the brief of the Attorney

General. He asks the Court to take a long stride into a field

where history is clear, traditions are long and emotions are

strong. W e ask the Court to exercise the restraint that

accords with its highest traditions.

22

State action is proper until it has been shown to be clearly

wrong. There has been no such showing in this case, either

before the court below or by the Appellants or by the At

torney General here. On the contrary, the evidence is, as the

court below found, that the State action is reasonable and

proper.

Dated December 7,1953.

Respectfully submitted,

T. Justin M oore

A rchibald G. R obertson

John W. R iely

H unton, W illiams, A nderson, T. Justin M oore, Jr.

Gay & M oore 1003 Electric Building

Of Counsel Richmond 12, Virginia

Counsel for the Prince Edward

County School Authorities

J. L indsay A lmond, Jr.

A ttorney General

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia

H enry T. W ick ham

Special Assistant to the

Attorney General

State-Planters Bank Building

Richmond, Virginia

For the Commonwealth of Virginia

Printed Letterpress by

L E W I S P R I N T I N G C O M P A N Y • R I C H M O N D , V I R G I N