Application for Stay and Recall of Mandate Pending Certiorari

Public Court Documents

May 3, 1978

16 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Application for Stay and Recall of Mandate Pending Certiorari, 1978. a80b1289-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c89acb03-1e20-4bd6-8fe5-a43728c721a8/application-for-stay-and-recall-of-mandate-pending-certiorari. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

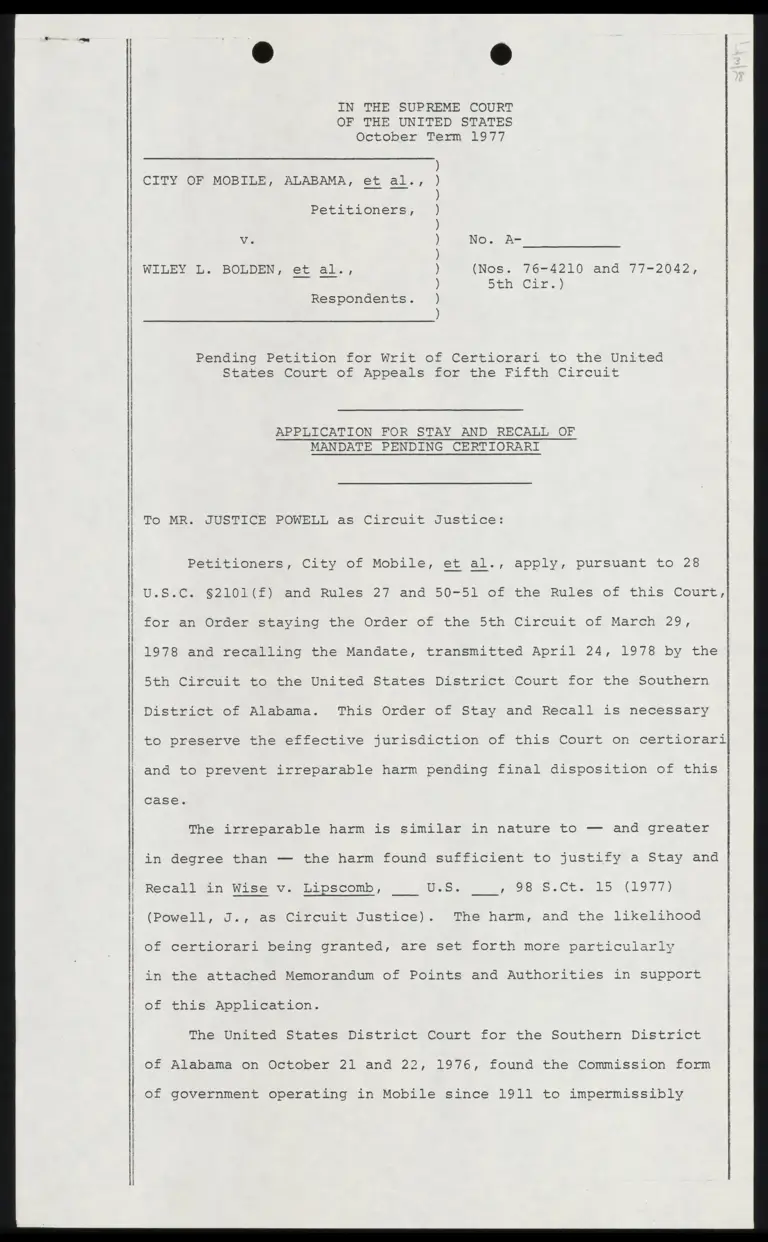

IN THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term 1977

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al., Petitioners,

Vv. No. A-

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al., (Nos. 76-4210 and 77-2042,

Beh Cir.)

Respondents.

N

a

t

?

N

e

a

”

S

a

”

N

u

”

N

a

?

N

a

t

”

S

a

t

’

S

a

S

a

S

e

”

Pending Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

APPLICATION FOR STAY AND RECALL OF

MANDATE PENDING CERTIORARI

To MR. JUSTICE POWELL as Circuit Justice:

Petitioners, City of Mobile, et al., ‘apply, pursuant to 28

} U.S.C. §2101(f) and Rules 27 and 50-51 of the Rules of this Court,

| for an Order staying the Order of the 5th Circuit of March 29,

1978 and recalling the Mandate, transmitted April 24, 1978 by the

5th Circuit to the United States District Court for the Southern District of Alabama. This Order of Stay and Recall is necessary

| to preserve the effective jurisdiction of this Court on certiorari

and to prevent irreparable harm pending final disposition of this

case.

The irreparable harm is similar in nature to — and greater

in degree than — the harm found sufficient to justify a Stay and

Recall in Wise v. Lipscomb, U.S. 1208 :S Ct, 15 (3977)

(Powell, J., as Circuit Justice). The harm, and the likelihood

of certiorari being granted, are set forth more particularly

in the attached Memorandum of Points and Authorities in support

| of this Application.

| The United States District Court for the Southern District

of Alabama on October 21 and 22, 1976, found the Commission form

of government operating in Mobile since 1911 to impermissibly

| pp. 109-110), set budget procedures (J. App., pp. 120-130) and

procedure for runoff elections (J. App. pp. 98-100), the compen-

118), the time of Council meetings (J. App. pp. 106-108), the

provided in detail the duties and supervision of City officials

who were not even to be elected, such as the Finance Director

districts. But the Commissioners' executive duties (Each Commis-

dilute the votes of black Mobilians and ordered elections to

Mayor and Councilmen from 9 single-member districts to be held

August 1977. 423 F. Supp. 384, 404 (5.D. Ala. 1976). The Court

recognized the reasonable debatability of the constitutional

necessity of ordering a change in the City's form of government,

423 F. Supp. at 384, and encouraged expeditious appeal. Id.

The District Court on March 9, 1977 issued an order imple-

menting in detail the change the Mayor-Council government (5th Cir}

J APPer DD. 52-145) This Order established the power, duties

and terms of office of the Mayor and Councilmen; the Court retain-

ed jurisdiction for 6 years (J. App., P. 94). The Court: drew the

district lines (J. App., pp. 96-97), established the time and

sation of election Councilmen and Mayor (J. App. pp. 101-105, 113-1}

power and limitations in the Council to grant franchises (J. App..,}

{J. ApP., Dp. 130-138).

The scope of the implementing Order could not have been other:

wise. For this was not merely a change from electing councilmen aj

large to electing them from several, smaller districts. This was

a Court-ordered change from Commission to strong-Mayor form of

government; Commissioners could not be elected from single-member

sioner heads a department: Public Works and Services, Public

Safety, and Finance, see 423 F. Supp. at 386) had to be fit into a

Mayor-Council scheme.

1/ For the convenience of the Court, copies of the October 1976

= and March 9, 1977 Orders of the District Court (as printed

in the Joint Appendix before the 5th Circuit), as well as the

Stay Orders of April 7, 1977 {(8.D. Ala.) and June 14, 1977

(5th Cir.), the 5th Circuit's opinion and Order on the merits

(slip op. 3408, with companion cases at slip op. 3373, 3419

and 3431, not here involved) and the Order of the 5th Circuit

denying stay of mandate (April 24, 1978) are attached.

—

—

—

—

I

—

—

—

The District Court on April 7, 1977 stayed its Order of

October 1976 and implementation Order of March 9, 1977. The

Court cited the confusion and irreparable harm if its Order of

Mayor-Council elections was reversed after elections had been held

(Order, pp. 2-3). Two changes in the form of government (first

to Mayor-Council, then back to Commission upon possible vacation

i of the District Court's implementing Order on appeal), with the

| attendant changes in appointed officials and operations (as pro-

vided in the District Court's detailed impelementation Order) were

seen as inefficient and threatening the very delivery of vital

government services. (Order, p. 4). The District Court expressly

balanced the speculative harm to black Mobilians of continuing,

pending appellate review, under a government elected under an

at-large system found by that Court to be unconstitutional. On

balance, the equities were in favor of staying implementation of

the Order changing to a districted Mayor-Council system (Order,

p. 5) pendente lite.

The District Court's analysis is as correct now as it was on

April 7, 1977. The District Court expressed no doubt about the

correctness of its findings and conclusions; but it was sufficient}

to merit a Stay that the points were reasonably debatable. (Order,

P. 6).

At oral argument, the 5th Circuit expanded the District

| Court's Stay by staying all elections pendente lite. (Order,

June 14, 1977). The case was argued June 13, 1977 and decided

March 29, 1978. No modification of the District Court's or Court

' of Appeals' stays was sought by Plaintiffs.

This Court of Appeals' June 1977 stay Order was dissolved

Hon March 29, 1978 (slip op. 3408, 3418). On April 24, 1978 the

5th Circuit (Tjoflat, J.) denied a Motion to Stay the issuance

of the Mandate pending certiorari. This Motion satisfies the

requirements of Rules 27 and 51(2) of the Rules of this Court.

The mandate has been transmitted to the District Court below by

denial of Motion to Stay Mandate. It would be futile and irre-

parable, time consuming and wasteful to move again for a Stay

before both the District Court and Court of Appeals below.

Therefore, this Application for Stay and Recall is timely

and ripe.

Petitioners ask only for the continuation of a stay already

found by the District Court and Court of Appeals below to be

merited. The status quo of a stay of elections pending appellate

review, for 1 year, produced no demonstrable harm to Plaintiffs

(Respondents here); the status quo avoided the irreparable harm

to black and white Mobilians alike recognized by the two Courts

E

S

S—

—

S

Y

S

W

B

S

A

R

A

A

T

below as ineluctable.

WHEREFORE, petitions urge that the revival (by Order of the

Court of Appeals, March 29, 1978) of implementation Order of

March 9, 1977 and the underlying Order of October 1976 be stayed,

and the mandate be recalled, pending disposition by this Court of

Petition for Certiorari, due on or before June 27, 1978.

Respectfully submitted,

Clone) pth x

C. B. Arendall, Jr.

Williams C. Tidwell, Fo

Travis M. Bedsole, Jr.

Post Office Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Fred G. Collins

City Attorney

City Hall

Mobile, Alabama 36602

Charles S. Rhyne

William S. Rhyne

Donald A. Carr

Martin W. Matzen

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Suite 800

Washington, D. C. 20036

(202) 466-5420

Attorneys for Petitioners

a

e

an

a

t

e

t

| entered Stays indistinguishable from the Stay sought herein.=

IN THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term 1977

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Petitioners,

Vv. A-

WILEY 1... BOLDEN, et al., (Nos. 76-4210 and 77-2042,

5th Cir.)

Respondents.

Pending Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND

AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF

APPLICATION FOR STAY AND

RECALL OF MANDATE

The Application sets forth the scope of the Orders of which

review 1s to be sought in this Court; the Application also indi-

cates that both the District Court and the Court of Appeals below

L/

In order to maintain the status quo (a stay of election and change to

| Court-ordered Mayor-Council form) by Order of this Court, Peti-

tioners must show: (1) irreparable harm, and (2) a "reasonable

probability that four members of the Court will consider the issue

sufficiently meritorious to grant certiorari." Wise v. Lipscomb,

28 8.Ct. 15,119 (1977) (Powell, J., as Circuit Justice), guoting

from Graves v. Barnes, 405 U.S. 1201, 1203 (1972), rev'd sub nom.

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973).

1/ This Stay is necessary because the Judgment of the 5th Circuit

to be reviewed, slip op. 3408, 3418, dissolved both stays and

reinstated the broad implementing Order of elections and

operations under a Mayor-Council form of government.

The Recall of Mandate is necessary because of the denial on

April 24, 1978 by the 5th Circuit (Tjoflat, J.) of Petitioners

Motion for Stay of Mandate.

This case presents the same issues present in Lipscomb and

Graves: whether a particular at-large electoral system dilutes

the votes of black citizens in a way prohibited by the 14th Amend-

ment.

The need for a Stay is more severe in this case than in

} Lipscomb or Graves. Those cases involved an Order changing only

the composition of the electorate voting for a particular office-

holder. This case involves as well an Order changing the form,

nature and duties of the officeholder. Commissioners, campaigningj

and serving as functional experts in a combined legislative-exe-

cutive role, are to be replaced by a Council with strong Mayor.

The ordering of salaries and duties of an entire City government

is a quantum more dislocating than the mere division of electoral

districts from one into nine.

At stake here is Mobile's existing form of government, not

| merely the manner of its election.

f

|

§

4

a

—

| must proceed to implement its order disestablishing Mobile's

|| existing Commission form of government and substituting therefor

| a Mayor-Council form elected by single-member district. From

i Plaintiffs here, as there, assert harm from delaying remedy. Here,

| as there, the issue of the constitutional appropriateness of the

| the holding of elections pursuant to the remedial Order.

black and white Mobilians, only to be fired and divested upon

MOBILE WILL SUFFER IRREPARABLE

HARM UNLESS STAY IS GRANTED

Upon issuance of th¢mandate, the District Court

this changeover, if it occurs, there is no practicable return.

The balance of equities here fits the pattern of Lipscomb.

Orders of the District Court below would be effectively mooted by

To the balance in favor of maintaining the status guo must

be added the irreparable harm to all Mobilians of tentative imple-

mentation pendente lite of an Order that a complete executive

branch of City government be hired, paid, invested with powers

defined by Court Order and entrusted to respond to the needs of

reversal of the Court of Appeals.

According to the "intensely local sppraisaindd of the Dis-

trict Court below (acceded to by the 5th Circuit at oral argu-

ment), this was irreparable harm not to be imposed pending appeal by requiring

a showing of certain error in the issuance of the Order subject

to appellate review. Nonetheless, reviewable and reversable

error there is.

2/ White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 770 (1973).

4

II.

THE PROBABILITY THAT CERTIORARI

WILL BE GRANTED IS SUBSTANTIAL

As in Wise v. Lipscomb, supra, this case involves the gov-

ernment of a "major city that has adhered to its tradition of

at-large elctions" for over 65 years. 98 S.Ct. at 19. Unlike the |

situation in Lipscomb, the continued existence of Mobile's commis

sion government requires the use of such an electoral system.

The Court of Appeals below recognized a continuum of accept-

ability of at-large voting systems. Court-ordered remedial plans

presumptively must be single-member districts. Greater deference

is accorded at-large plans established by State or local legisla-

tive or electoral act; greater deference still is accorded at-

large plans adopted long ago.

This case represents a further step on the continuum of

deference: at-large plans adopted long ago, not simply because of

an intrinsic preference for at-large plans to assure City-wide

perspective, but because Commissioners constitationalive) must

be elected at-large. To order a change in Mobile is to undo not

just at-large elootions?’ but a form of administration of 67

yvears' standing.

To be sure, locally adopted at-large plans can be undone.

But only on an evidentiary showing which increases along the

B/

continuum of deference.=

3/ The District Court below so found. 423 F. Supp. 384, 387

(S.D. Ala. 1976).

{

4/ Cf., Zimmeyr v, MoXeithen, 485 F.2d 1297, 1301 (3th Cir. 1973)

(en banc), aff'd sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Board t

v. Marshall, 424 U.85. 636 (1976) (at-large plan adopted in

1968 to avoid one-man-one-vote difficulties).

5/ This is merely a weighting of the interest of the State or

3 City in maintaining its plan. The government's interest has

been a principal factor in the dilution eguation since White

v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) as embellished by Zimmer,

485 7.24 1297, 1305 (8th Cir. 1973) (en banc).

The basis upon which the City's form of government is to be

abrogated involved adjudication of constitutional principles which

are both complex and difficult of application, especially so in light of the unique facts of this case.

For example, the District Court had found that black

| Mobilians were able freely to register, vote, and seek office

(423 F. Supp. at 387, 399), vet no serious black candidate had

ever run for the City Commission and carried predominantly black

wards only to be defeated by racially polarized voting (423 F.

Supp. at 388). And the record clearly demonstrated that black

| citizens enjoyed and used real electoral power, with all candi-

dates actively seeking black votes which in fact constituted the :

T

I

"swing vote" in the City's most recent election. (J. App. Z247~

250).

To conclude on such facts that black Mobilians are "denied |}

access" to the City's political processes is to improperly equate |

the purported difficulty of black voters in electing black offi-

cials with the existence of a constitutional violation, contrary

+0 the teachings of Whitcomb v., Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 149 (1571),

Beer v. United States, 425 U.8. 130, 136 n. 8 (1976), and United

ii Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 165+ me

5

F

{

v

67 (1977). Indeed, this case is totally unique in its finding

of "dilution" where no black candidate viable even with black

voters has ever run for election.

Quite apart from the issue of whether the Court could properly

hold Mobile's electoral system discriminatory in effect, the

further issue is whether any such effect is the result of invidious

racial purpose. For under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend-

6/

ments ,—~ the question is whether Mobile's commission form of

6/ With this, the 5th Circuit agreed in the companion case to

Mobile, Nevett v. Sides, slip op. 3373, 3382, 3385 f{Mar.

29,1978).

C

T

A

T

E

A

P

R

A

Hrs

age

w

—

—

—

—

T

y

v

government represents purposeful discrimination against, or a

purposeful contrivance to dilute the voting strength of black

citizens. See United Jewish Organizations, supra, 430 U.S. at

179 (Stewart, J. concurring). The Court of Appeals has now

correctly held, as the District Court did not, that proof of

such a purpose 1s an essential element in voting dilution cases.

Yet the legal standard of proof of such intent applied by the

Court in this case is in conflict with the principles enunciated

by the Supreme Court in several recent cases.

The essence of the Court of Appeals' holding is that where

application of the criteria set out in Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485

F.28 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc), affirmed sub nom. East

Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976)

("without approval of [its] constitutional views", 424 U.S. at

638), indicates a current condition of voting dilution, the

maintenance of such a system without affirmative corrective actior

compels the inference of purposeful dilution. Slip op. at 3416-

17.

The Court, in proffering a circumstantial test of intent,

did not distinguish between electoral plans newly created or

UW changed, and those neutrally adopted and long maintained.-— i fio

8/ melded cases involving Court-ordered districting— with cases

involving maintenance of a system of administration, without

7/ Nevett v. Sides (Nevett Il), slip op. 3373, 3393 (Mar. 29,

1978):

"The ultimate issue in a case alleging uncon-

stitutional dilution of the votes of a racial

group is whether the districting plan under

attack exists because it was intended to di-

mish or dilute the political efficacy of that

group." (emphasis added).

8/ E.g., Birksey v. Board of Hinds County, 554 F.28 139, 140

(5th Cir. 19877) (en banc), cert. denied, U.S. 98

S.Ct. 512 41977).

r

e

—

—

—

—

—

change and without prior judicial intervention, for 67 years.

See Nevett II, slip op. 3373, 3384 n. 13 at 3385, 3387. Compare

Wise v. Lipscomb, 98 S8.Ct, 15, 17 (1977) (Powell, J., as Circuit

Justice).

It is clear that even where minority voters are in fact

substantially disadvantaged in their ability to elect minority

candidates by an existing electoral plan in the presence of

racially polarized voting, no per se constitutional violation

exists and there arises no constitutional or statutory duty of

"affirmative action" by the legislature to correct the situation.

United Jewish Organizations, supra, 97 S.Ct. at 1010; Beer, supra

425 U.S. at 141 (Voting Rights Act requires only that changes not

o/ be retrogressive) .= Yet the Court's decision in effect retro-

actively imposes just such a duty.

Recent cases also contradict the Court's apparent notion

that either action or inaction, coupled with awareness of racial

impact, compels the inference of racial purpose. For example,

if awareness of racially disproportionate impact were equivalent

to an invidious intent to accomplish such impact, the outcome of

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), where the police depart

ment continuted to administer its employment test despite its

awareness that a disproportionate number of black applicants

failed, 426 U.S. at 252, would necessarily have been different.

Similarly in Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housingj

ir

Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977), zoning officials were

well aware that existing policies had the effect of maintaining

the "nearly all white" status of the village, and the Court of

9/ Indeed, the action of the Alabama legislature in assigning

specific functions to the City Commissioners, which the

Court of Appeals found so "probative" of racial purpose

{slip op. 3408, 341ll n. 2, 3416-17), was clearly a non-retro-

gressive enactment. Act 283 in fact merely codified the

longstanding practice of the commissioners' undertaking of

specific functions, archetypal of the commission form of

government. It merely added a functional designation to the

already numbered place on the Commission for which every

candidate had to announce and run.

E

p

—

—

oe

Appeals had held that they "could not simply ignore this problem.

429 U.S. at 260. Yet the Supreme Court upheld the maintenance of

these policies for reasons racially neutral, despite their ex-

clusionary effect.

Where, as in Mobile, the official policy or action challengeq

is both facially neutral and serves legitimate governmental in-

terests, it is the clear teaching of these cases that an invidious

racial purpose may not so lightly be inferred. Particularly

because the legislative action necessary here to avoid the lower

Courts' condemnation would have required not merely redistricting

but a complete restructuring of Mobile's existing system of gov-

ernment, the evidence here in no way warrants such an inference.

Indeed, because this case is one in which black citizens plaved

a significant role in the City's politics of racial coalition

rather than supporting separate black candidacies, it is impos-

sible to impute to the Commissioners an invidious intent to

suppress black voting strength which might logically arise from

serious challenges by black candidates for their posts.

The factor of purpose — and the principle of the Court of

Appeals below that purpose is shown by maintenance of a form of

government innocently adopted — returns us in closing to the

continuum of deference. Like Wise v. Lipscomb, supra, this case

concerns the standards of judicial scrutiny applicable to a

legislative electoral plan which utilizes at-large representa-

tion to further a valid municipal interest. 98 S.C:-. at 17-18.

But, in contrast to Lipcomb, the issues here revolve around the

"constitutional liability" of Mobile's form of government to

judicially-imposed change, rather than centering on standards for|

court approval of legislative plans proffered to remedy on un-

constitutional electoral system.

This Court has correctly observed that "viable local gov-

ernments may need considerable flexibility in local arrangements”

in order to meet local needs. Abate v. Mundt, 403 U.S. 182,

186-87 (1971). At-large electoral systems, integral and

f

d

>

constitutionally necessary to the commission form of government

used by approximately 3% of this Nation's 18,500 municipali- ties, 33 further valid governmental objectives and are entitled

to at least "limited deference." Lipscomb, supra, 98 S5.Ct. at

17:n.,.2.

| The test of invidious intent applied below stands "de-

| ference" on its head. The City's long history of Commission

Government is anomalously used to rationalize its abolition. See

slip op. at 3414-15. Fundamental changes of a city's form of

I

T

T

P

P

TI

A

T

T

I

government are an exceptional event, and yet the Courts below

have cast the unexceptional — homeostasis — into a racial mold

i with apparent ease. The Court of Appeals here has applied a

transparently "tort standard" of discriminatory intent which

| affixes liability for conduct at most negligent and not invidiously

motivated.

At its worst, the "purpose-maintenance" test is an invita-

tion to the City to proffer an affirmative defense to a showing

of discriminatory effect 22 in much the same way that employment

| discrimination cases demand a showing of job-relatedness to re-

.

1/ The necessity sist a clear showing of discriminatory effect.

of at-large elections to the maintenance of the Commission form

is that affirmative defense. It stands of record here, unrebutted

10/ The Municipal Year Book, International City Management

Association, Tables 2 and 1/1 (1976).

ll/ As pointed out above, the Findings of the District Court

| below will not support even the ultimate finding of dis-

criminatory effect.

In passing, we note that findings of ultimate fact are

entitled to none of the phlegmatic review given under the

"clearly erroneous" standard. E.g., Causey v. Ford Motor

Co., 516 P.28 416, 420-21 (5th-Cir., 1975).

12/ The required strong showing has been absent in innocently

ha adopted plans whose maintenance had the effect of maintain-

ing the effects of other, unrelated, acts of discrimination.

E.g., International Bro. of Teamsters v. U.S., 431 U.S. 324,

356 (1977).

rr o

r

m

—

—

® @

10

by the opinions of the Courts below. For even if the legislative

choice to maintain Mobile's existing government were "motivated

in part by a racially discriminatory purpose", this choice should

have been upheld where the same decision "would have resulted"

from other legitimate governmental concerns. Village of Arlingtor

Helghts, supra, 42% U.S. at 271 n. 21. Neither the record nor

the opinions below disclose any basis for the Courts' implicit

and implausible assumption that Mobile's present form of govern-

ment would be different but for a putative racial animus. The

error below is palpable, as is its potential capacity to put in

jeopardy historically at-large electoral plans wherever there

exists a substantial minority population.

The 5th Circuit took the occasion of Mobile's appeal and

three companion case’ to rethink its approach to dilution

cases.tt/ The large number of dilution cases, the necessity to

resolve finally the application of the intent requirement of

Davis and Arlington Heights, and the effect of weighing choices

made by voters about their very form of government against the

effect and intent of the size of electoral districts, all make

this a case susceptible to review by this Court under 28 U.S.C.

$1254{1) or (2),

13/ Nevett v. Sides (Nevett II), slip op. 3373; Blacks United

v. Shreveport, slip op. 3419; and Thomasville Branch,

N.A.A.C.P. v. Thomas County, slip op. 3431 {all March 29,

1978).

l4/ The Court recognized the difficulty of District Courts in

fe administering this area of constitutional law with imper-

fect appellate guidance, Nevett II, slip op. 3373, 3391

(addressing " . language in several opinions of this cir-

cuit that has caused some apparent confusion in this changing

and complex area of the law. . .").

J

1

In sum, the ultimate outcome of this action is of vital

importance not only to the City, but to every local government

with the need or traditional preference for at-large elections.

The constitutional issues here presented are substantial and im-

portant, and of precisely the nature which frequently moves the

Supreme Court to grant review.

Respectfully submitted,

Cops 4 LEN

C. B. Arendall,6 Jr.

Williams C. Tidwell,

Travis M. Bedsole, 4

Post Office Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Fred G. Collins

City Attorney

City Hall

Mobile, Alabama 36602

Charles S. Rhyne

William S. Rhyne

Donald A. Carr

Martin W. Matzen

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N. W.

Suite 800

Washington, D.. CC. 20036

Attorneys for Petitioners

pr

oa

y

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that a copy of the foregoing Application for Stay

and Recall of Mandate and Memorandum in support thereof have

been served upon opposing counsel of record, and upon Amicus,

by placing the same properly addressed in the United States Mail

with adequate postage affixed thereto this ny day of May, 1978.

20.8 ¢

Attorney for Petiti