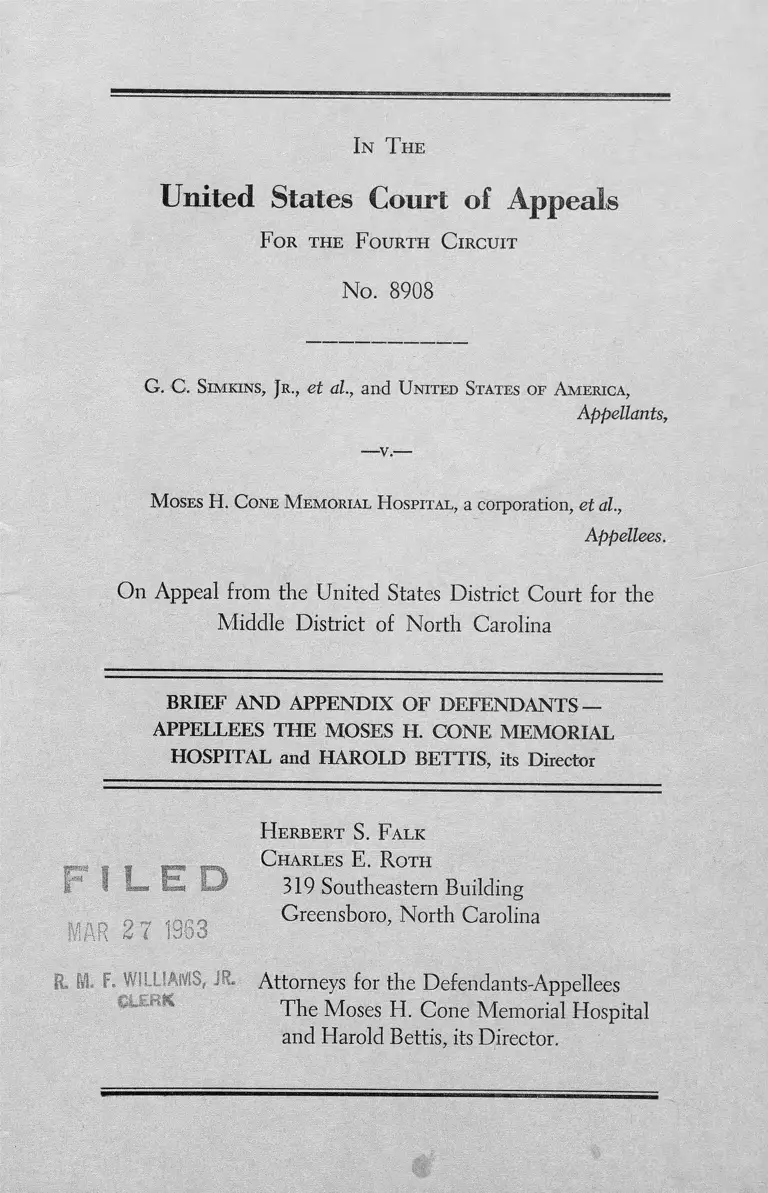

Simkins v Moses H Cone Memorial Hospital Brief and Appendix of Defendents

Public Court Documents

March 27, 1963

52 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Simkins v Moses H Cone Memorial Hospital Brief and Appendix of Defendents, 1963. be5a9f66-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c89d5194-c41d-4edc-b6b1-a6064c3826bb/simkins-v-moses-h-cone-memorial-hospital-brief-and-appendix-of-defendents. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

In T he

United States Court of Appeals

F or th e F ourth C ircuit

No. 8908

G. C. Simkins, Jr., et al., and United States of America,

Appellants,

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, a corporation, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina

BRIEF AND APPENDIX OF DEFENDANTS —

APPELLEES THE MOSES H. CONE MEMORIAL

HOSPITAL and HAROLD BETTIS, its Director

-v.-

H erbert S. F alk

319 Southeastern Building

Greensboro, North Carolina

. F. WILLIAMS, JR* Attorneys for the Defendants-Appellees

The Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital

and Harold Bettis, its Director.

%

INDEX TO BRIEF

Page

Statement of the C a se _____________________________ 1

Preliminary Statement___________ ..._________________ 2

Argument _____________ ___________________________ 3

I. T he F ederal C ourts D o N ot H ave Jurisdiction

of Actions B y Individuals S eeking R edress for

the A lleged Invasion o f T heir C ivil R ights by

O ther Individuals or Private C orporations__ 3

II. T he D efendants A re Private Persons and C or

porations, and N ot In stru m en ta lities of G ov

er n m en t E ither State or F e d e r a l _____________ 5

(1) The method, of selecting the Trustees of the

Moses Cone Hospital does not affect the pri

vate character of that corporation _________ 6

(2) The ad valorem tax exemptions of the two hos

pitals do not affect their character as private

corporations ____________________________ 13

(3) The licensure of the two hospitals by the State

of North Carolina does not make them agen

cies of the S ta te_______________ 14

(4) The nursing programs at the Moses Cone Hos

pital do not affect the private character of that

corporation _____________________________ 17

l

(5) The grants of Hill-Burton funds to the two hos

pitals do not make them instrumentalities

either of the Federal government or of the State 19

(6) Neither the Federal government nor the State

exercises any control over the two hospitals

through the Hill-Burton A c t____________ 22

(7) The whole is no greater than the sum of the

parts _____________________________ 28

(8) In reference to the position of the American

Civil Liberties Union_____________________ 32

(9) In reference to the two individual defendants,.. . 32

III. T he C onstitutionality of th e C hallenged Pro

visions of the H il l -Burton Act Is Irrelevant

and Is N ot B efo re th e C ourt in T his Action ..^ 33

Conclusion _______________________________________ 37

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U. S. 715 (1961) ____________ 5, 14, 29, 30, 31

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Board of

Directors of City Trusts of City of

Philadelphia, 353 U. S. 230 (1957) ______________ 12

Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U. S.

(4 Wheat.) 518 (1819) _________________ 8, 9, 10,

13, 24, 37

Eaton v. Board of Managers of James Walker

Memorial Hospital, 164 F. Supp. 191

(E.D.N.C. 1958), aff’d., 261 F. 2d 521

(4th Cir. 1958), cert, denied, 359 U. S.

984, (1959) __________ ____________11, 12, 13, 17,

20, 30, 31, 32

Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320

(5th Cir. 1962), cert. den. sub nom.

Ghioto v. Hampton, 9 L. Ed. 2d 170____29, 30, 31, 37

Harrison v. Murphy, 205 F. Supp. 449

(D. C. Del. 1962) _____________________________ 30

Khoury v. Community Memorial Hospital, Inc.,

203 Va. 236,123 S. E. 2d 533 (1962) ____21, 24, 27, 37

Mitchell v. Boys Club of Metropolitan Police,

D. C., 157 F. Supp. 101 (D.C.D.C. 1957) 13, 14, 20

National Federation of Railway Workers v.

National Mediation Board, 110 F. 2d 529

(D. C. Cir. 1940), cert, denied, 310 U. S.

628 (1940) ___________________________________ 4

Norris v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore,

78 F. Supp. 451 (D. C. Md. 1948) ________ 10, 13, 20

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) __________ 22, 33

Watkins v. Oaklawn Jockey Club, 183 F. 2d

440 (8th Cir. 1950) ___________________________ 33

Williams v. Howard Johnsons Restaurant,

268 F. 2d 845 (4th Cir. 1959) ...._ .._ .15 , 16, 17, 26

Williams v. Yellow Cab Co. of Pittsburgh, Pa.,

200 F. 2d 302 (3d Cir. 1952), cert, denied,

346 U. S. 840 (1953) __________________ ____ ...___ 3

28 U. S. Q , $1331 ______________________________ 3, 4

28 U. S. C , §1343 (3) ___________________________ 3, 4

42 U. S. C., §291 et seq__________ :________________ 19

42 U. S. C., §291 _____________________________ 23, 24

42 U. S. C., §291e (f) __________________________27, 33

42 U. S. C , §291m ________________________27, 28, 36

N. C. Gen. Stats., §20-7__________________________16

N. C. Gen. Stats., §20-50 ________________________ 16

N. C. Gen. Stats., §84-4_________________________ 16

N. C. Gen. Stats., §90-18________________________ 16

N. C. Gen. Stats, §90-29 ________________________ 16

N .C . Gen. Stats, §131-126.3_____________________14, 15

N. C. Gen. Stats, §131-126.4___________________ 14, 15

Private Laws of North Carolina, Session of 1913,

Chapter 400 _______________ 7

Hearings before the Senate Committee on Education

and Labor on S. 191, 79th Cong, 1st Sess.______25, 26

iv

In T he

United States Court of Appeals

F or th e F ourth C ircuit

No. 8908

G. C. S im k in s , Jr ., et al., and U nited States of Am erica ,

Appellants,

M oses H . C one M em o rial H ospital, a corporation, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina

BRIEF OF THE MOSES H. CONE MEMORIAL

HOSPITAL and HAROLD BETTIS, its Director

STA TEM EN T OF TH E CASE

This action was instituted in the District Court ostensibly

to redress grievances which were alleged to arise under the

Fourteenth and the Fifth Amendments to the United States

Constitution. The defendants asserted in the court below

that the Fourteenth Amendment is concerned solely with

State action and the Fifth Amendment solely with Federal

action; that these defendants are private corporations and in

dividuals and not in any way instrumentalities either of the

State or of the Federal government, and that the District

Court therefore had no jurisdiction of the subject matter of

the action; and the defendants moved to dismiss the com

plaint on that ground. Judge Stanley adopted this view in his

2

careful and admirably documented opinion of December 5,

1962, and entered judgment on December 17, 1962, denying

motions for summary judgment by the plaintiffs and the

United States, and granting the motions of the defendants to

dismiss the complaint and the pleading in intervention for

lack of jurisdiction over the subject matter of the action. The

matter is before this Court on appeal by the plaintiffs and the

United States from that judgment.

PRELIM INARY STA TEM EN T

It is well not to forget—in small questions of Hill-Burton

construction requirements and in large questions of consti

tutionality—that we are before this Court, at this time and on

this appeal, solely on the fundamental legal issue of the juris

diction of the District Court over the subject matter of the

action. The District Court does not have jurisdiction of ac

tions by individuals seeking redress for the alleged invasion of

their civil rights by other individuals or private corporations—

and it is the position of the defendants that this is such an

action, and nothing more.

The appellants have devoted a great deal of attention to

making something more of the case. For the first time in the

history of his office, the Attorney General of the United

States, the King’s champion, has raised his lance against the

King. He himself concedes that this action is “ exceptional”

(U. S. Brief, p. 40), but greater candor would make the word

“ unprecedented” — the defendants were able to find no prece

dent for his action, and under inquiry in the court below, the

Attorney General was able to cite no precedent. It is perhaps

fortunate in these “exceptional” circumstances that the

shadow of the windmill at which he is tilting does not actually

fall across the present case.

The plaintiffs asserted in the court below that this was a

case of first impression — but the case has actually been de

3

cided many times before in reference to schools, and restau

rants, and golf courses, and swimming pools, and even hos

pitals, and the principles which govern it are well settled and

have been thoroughly defined in this Circuit. If the facility—

whether it be a restaurant, or a golf course, or a hospital — is

a public one (in the constitutional sense), it is subject to the

constitutional amendments and discrimination is unlawful

under them. If the facility is a private one, however, it is not

subject to the constitutional amendments — and the Federal

courts do not even have jurisdiction to consider the matter of

discrimination.

The issue of jurisdiction therefore hinges on the one basic

question — no matter how it is phrased — of whether these

defendant hospitals are public corporations in the constitu

tional sense or private ones free from constitutional restraints.

ARGUM ENT

I. THE FEDERAL COURTS DO NOT HAVE JURISDICTION

OF ACTIONS BY /INDIVIDUALS SEEKING REDRESS

FOR THE ALLEGED INVASION OF THEIR CIVIL

RIGHTS BY OTHER INDIVIDUALS OR PRIVATE COR

PORATIONS.

The jurisdiction of the District Court in this action was

invoked pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Section

1343 (3). (Complaint |[I, at 4 a ) . Under this section, neither

diversity nor a jurisdictional amount is required, but the sec

tion nonetheless has a limited application, and it confers origi

nal jurisdiction upon the Federal District Courts to entertain

those civil actions—and only those civil actions—which are

founded on the Fourteenth Amendment and its implement

ing legislation. Williams v. Yellow Cab Co. of Pittsburgh,

Pa., 200 F. 2d 302, 307 (3d Cir. 1952), cert, denied, 346 U.

S. 840 (1953). The jurisdiction of the District Court in this

action was also invoked under Title 28, United States Code,

4

Section 1331 on the ground that the amount in controversy

exceeded $10,000.00, and that the action was founded on

invasions of the rights guaranteed by Section 1 of the Four

teenth Amendment and by the Fifth Amendment. (Com

plaint ([1, at 4 a ) .

The plaintiffs therefore relied for jurisdiction in the court

below upon invasions of the guarantees of the Fourteenth

Amendment under both Sections 1343 (3) and 1331, and of

the guarantees of the Fifth Amendment under Section 1331;

and it is clear that the District Court has no jurisdiction under

either Section 1343(3) or Section 1331 unless the depriva

tions alleged by the plaintiffs are deprivations of those rights

guaranteed either by the Fourteenth Amendment or by the

Fifth Amendment. The inhibitions of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, however, are inhibitions solely against State action, and

the inhibitions of the Fifth Amendment are inhibitions solely

against Federal action; and neither Amendment applies to

action by private persons or corporations.

“The guarantees of the 14th amendment, U.S.C.A.

Const., relate solely to action by a state government, clearly

absent here. Hence, any constitutional rights pertinent to the

instant case are those guaranteed by the 5th amendment. De

cisive of this constitutional issue is the established proposition

that the 5th amendment relates only to governmental action,

federal in character, not to action by private persons.” Vinson,

Associate Justice, speaking in National Federation of Railway

Workers v. National Mediation Board, 110 F. 2d 529, 537

(D.C. Cir. 1940), cert, denied, 310 U. S. 628 (1940).

It is idle to cumulate citations, for these principles are well

settled and have not been disputed by the appellants. Noth

ing could be clearer than that “The guarantees of the Four

teenth Amendment . . . relate solely to action by a state gov

ernment,” and “ that the Fifth Amendment relates only to

governmental action, federal in character, (and) not to action

5

by private persons” ; and with these premises, we are back

again to the basic question which is determinative of the

right of the plaintiffs to bring this action in the Federal courts:

Whether The Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and the

Wesley Long Community Hospital are private corporations,

or public corporations either State or Federal in character.

II. TH E DEFENDANTS ARE PRIVATE PERSONS AND

CORPORATIONS, AND NOT INSTRUMENTALITIES OF

GOVERNMENT EITHER STATE OR FEDERAL.

The plaintiffs have taken exception (Plaintiffs’ Brief, p.

34) to Judge Stanley’s undertaking to determine if the de

fendant hospitals were “public corporations,” and they urged

the court below to consider the “ totality” of governmental

involvement. The word “ totality” is one upon which the

plaintiffs have placed great emphasis, apparently on the basis

of inferences drawn by them from the Burton case1 which

have led them to conclude — or at least to suggest — that the

whole is somehow greater than the sum of the parts. The

plaintiffs do Judge Stanley an injustice, however, for he made

it quite clear that in determining whether the defendants were

subject to the constitutional amendments, he felt it “neces

sary” — in his own words — “ to examine the various aspects

of governmental involvement which the plaintiffs contend

add up to make the defendant hospitals public corporations

in the constitutional sense” (207a. Emphasis added), and

after examining each such aspect, he then went on to con

sider expressly the “Total Governmental Involvement and

Participation” (217a) .

The plaintiffs still suggest in this Court that our question

is “Whether the appellees’ contacts with government are suf

ficient to place them under the restraints of the Fifth and

1 Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715 (1961).

6

fourteenth Amendments against racial discrimination.” This

may seem to the plaintiffs a more euphemistic inquiry than

whether the defendant hospitals are “public corporations” or

even “ public corporations in the constitutional sense”—but

no amount of euphemism can conceal the ultimate spade. It

is the same question still—and it can still be resolved only by

the same examination of the “points of contact” of the de

fendant hospitals with government which was made in the

District Court.

The plaintiffs — in the court below — suggested five of

these points of contact of the defendant hospitals with gov

ernment/ All were examined carefully and debated fully; it

was determined that each was insignificant in itself, and that

the whole was no greater than the sum of the parts; and Judge

Stanley therefore determined that the defendant hospitals

were not “ instrumentalities of government in the constitu

tional sense” and are not “ subject to the inhibitions of the

Fifth Amendment or the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution” (221a). These points of contact

we are now here to debate once again.

(1) The method of selecting the Trustees of the Moses Cone

Hospital does not affect the private character of that

corporation.

The history of the Moses Cone Hospital and its Board of

Trustees appears fully in our record and is summarized care

fully by Judge Stanley in his opinion (198a), and we shall

not belabor it here. The hospital was originally incorporated

in 1911 as a private corporation under the general corporation

laws of North Carolina. There were ten original incorpora

tors, all of whom were private citizens and four of whom were

members of the Cone family, and these ten incorporators were

named as the first Board of Trustees of the corporation. The 2

2 All five apply to Moses Cone Hospital; only three of them apply to Wesley

Long.

7

corporation was subsequently granted a legislative charter by

a Private Act of the North Carolina General Assembly3 which

‘'fully ratified, approved, and confirmed” the original Articles

of Incorporation.

The charter of the hospital provided for a Board of Trus

tees of fifteen members, three to be named by the Governor

of North Carolina, one by the City Council of the City of

Greensboro, one by the Board of Commissioners of the

County of Guilford, one by the Guilford County Medical

Society, and one by the Board of Commissioners of the

County of Watauga. The charter then provided that Mrs.

Bertha L. Cone (Mrs. Moses H. Cone), who was the founder

and principal benefactor of the corporation, should have the

power to appoint the remaining eight trustees so long as she

might live; and that after her death or earlier if she should

renounce her right to appoint, the eight trustees originally

appointed by her should perpetuate themselves by the elec

tion of the Board of Trustees (199a).

Mrs. Bertha L. Cone died in 1947, and the charter of the

corporation was amended in 1961 to eliminate the appoint

ment of one trustee by the Board of Commissioners of the

County of Watauga. The eight trustees originally appointed

by Mrs. Cone and the one trustee originally appointed by

Watauga County, or a total of nine members of the fifteen-

member Board, are now to be perpetuated through the elec

tion of the Board of Trustees (199a).

The trustees appointed by public officials or agencies have

always been a minority of the trustees of the corporation

(199a) . There is no allegation or evidence whatever in our

record that any of the appointors of the Moses Cone trustees

have ever attempted to instruct or control their appointees as

trustees, or to exert any control over the corporation through

those appointees; or to indicate that the appointors have ever

3 Chapter 400, Private Laws of North Carolina, Session of 1913 ( 32a).

8

done anything more than to appoint distinguished private citi

zens — “ eminent and respectable individuals” — to serve the

corporation (cf. 208a).

The plaintiffs have advanced the theory that because six

members of the Moses Cone Hospital’s fifteen-member Board

of Trustees are named by public officials or agencies to serve

the private corporation, this somehow affects the private char

acter of the corporation. It is certainly not a new suggestion;

it was made in 1819 in the Dartmouth College case,4 and per

haps even then not for the first time. Dartmouth College

was originally incorporated under a crown charter from

George III dated December 13, 1769; and this original

charter provided for twelve trustees, to be self-perpetuating.

The original twelve trustees were all named in the charter

by the crown, and among them were the Governor of the

Province of New Hampshire, the President and two members

of the Council of the Province, the Speaker of the House of

Representatives in the Province, and “one of the assistants of

our colony of Connecticut.”

It was obviously suggested there — as here — that because

the trustees were appointed by public authority the corpora

tion therefore became public, and Chief Justice Marshall

said:

“ It has been urged repeatedly, and certainly with a de

gree of earnestness which attracted attention, that the

trustees deriving their power from a regal source, must

necessarily partake of the spirit of their origin; * * * . The

first trustees were undoubtedly named in the charter by

the crown; but at whose suggestion were they named? By

whom were they selected? The charter informs us. Dr.

Wheelock had represented 'that, for many weighty rea

sons, it would be expedient that the gentlemen whom he

4 Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U. S. (4 Wheat.) 518 (1819).

9

had already nominated in his last will, to be trustees in

America, should be trustees of the corporation now pro

posed.' When, afterwards, the trustees are named in the

charter, can it be doubted that the persons mentioned by

Dr. Wheelock in his will were appointed? Some were

probably added by the crown, with the approbation of

Dr. Wheelock. Among these is the doctor himself. If any

others were appointed at the instance of the crown, they

are the governor, three members of the council, and the

speaker of the house of representatives of the colony of

New Hampshire. * * * The original trustees, then, or

most of them, were named by Dr. Wheelock, and those

who were added to his nomination, most probably with

his approbation, were among the most eminent and re

spectable individuals in New Hampshire.” 17 U. S.

(4 Wheat.) 518,648-9.

It was held — in the Dartmouth College case in 1819 —

that all of the trustees appointed by the crown were private

trustees, and that neither their appointment by the crown

nor the public offices held by half of their number affected

the privacy of the corporation which they served as trustees.

Mr. Justice Story, in a full discussion, then went on to formu

late the classic distinction between public and private corpo

rations:

“Another division of corporations is into public and

private. Public corporations are generally esteemed such

as exist for public political purposes only, such as towns,

cities, parishes, and counties; and in many respects they

are so, although they involve some private interests; but

strictly speaking, public corporations are such only as are

founded by the government for public purposes, where the

whole interests belong also to the government. If, there

fore, the foundation be private, though under the charter

of the government, the corporation is private, however ex

10

tensive the uses may be to which it is devoted, either by

the bounty of the founder or the nature and objects of the

institution.” 17 U. S. (4 Wheat.) 518, 668.

# # #

“This reasoning applies in its full force to eleemosy

nary corporations. A hospital founded by a private bene

factor is, in point of law, a private corporation, although

dedicated by its charter to general charity.” 17 U. S. (4

Wheat.) 518,669.

$ * *

“When, then, the argument assumes, that because the

charity is public the corporation is public, it manifestly

confounds the popular with the strictly legal sense of the

terms. * * * When the corporation is said at the bar to be

public, it is not merely meant that the whole community

may be the proper objects of the bounty, but that the gov

ernment have the sole right, as trustees of the public

interests, to regulate, control, and direct the corporation,

and its funds and its franchises, at its own good will and

pleasure.” 17 U. S. (4 Wheat.) 518, 671. (Emphasis

added.)

It is as true today as it was in 1819 that trustees appointed

by public agencies to serve a private corporation, as in our

present case, do not thereby become public officials — any

more than did the trustees of Dartmouth College because

they were appointed by the crown. “To make a corporation

public, its managers, trustees, or directors must be not only

appointed by public authority but subject to its control. I

understand this to be the well established general law result

ing from both federal and state decisions.” Norris v. Mayor

and City Council of Baltimore, 78 F. Supp. 451, 458 (D. C.

Md. 1948). And even if these trustees did become public

representatives in any sense by virtue of their appointments,

11

they have always been and still are in the minority here; and

the Moses Cone Hospital therefore clearly remains — as the

District Court found — a private corporation decisively con

trolled by its private trustees who constitute (and have al

ways constituted) a clear majority of its Board of Trustees.

In Eaton v. Board of Managers of James Walker Memo

rial Hospital/ the James Walker Memorial Hospital was origi

nally chartered by the General Assembly of North Carolina;

and its original Board of Managers consisted of nine persons,

three of whom were elected by the Board of Commissioners of

New Hanover County and two by the Board of Aldermen of

the City of Wilmington, and only four of whom were selected

by Mr. James Walker. The Board of Managers was self-per

petuating, and at the time the action was instituted, none of

the original managers was still on the Board. The action was

dismissed for lack of jurisdiction on the ground that the James

Walker Memorial Hospital was a private corporation, and that

the acts of discrimination complained of therefore did not

constitute State action; and this Court affirmed the District

Court decision saying “The plaintiffs rightfully confine their

effort on this appeal to showing that the hospital is an instru

mentality of the State. . . . We may not interfere unless there

is State action which offends the Federal Constitution. From

this viewpoint we find no error in the decision of the District

Court for the facts clearly show that when the present suit

was brought, and for years before, the hospital was not an in

strumentality of the State but a corporation managed and

operated by an independent board free from State control.”

261 F. 2d 521, 525.

In our present case, no more than a minority of the Moses

Cone Hospital trustees have ever been appointed by public

authority. In the Eaton case, a majority of the original 5

5 164 F. Supp. 191 (E.D .N.C. 1958), affd ., 261 F. 2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958),

cert, denied, 359 U. S. 984 (1959).

12

Board of Managers was appointed by public authority. In the

Dartmouth College case decided in 1819, as we have seen, all

of the original trustees were appointed by public authority;

and lest this be thought to represent an archaic position, in

the Girard College case, not ultimately disposed of until 1958,

all of the trustees were again appointed by public authority.

The plaintiffs have persistently cited the original Supreme

Court decision in the Girard College case,6 and have persist

ently ignored the subsequent history of that case; but this en

tire history is detailed by Judge Soper in his opinion in the

Eaton case, and the Girard College case shows unmistakably

that the mere appointment of trustees by public authority does

not affect the character of a private corporation or agency.

The United States Supreme Court decision in the Girard

College case in 1957 was based — in Judge Soper’s words —

“ only on the ground that the managing board then in control

of the college had been constituted an agency of the State by

the enabling act and was therefore subject to the Fourteenth

Amendment; but . . . the new board thereafter set up by the

Orphans’ Court of Philadelphia, being composed of private

citizens, was not a State agency and was therefore free to carry

out the terms of the Girard will. . . . The court (i.e., the Su

preme Court of Pennsylvania) also held that the removal of

the old and the substitution of new trustees by the court did

not constitute State action within the scope of the Amend

ment; and it rejected the theory that State action is inherent

in charitable trusts generally even if they are not administered

by an agency of the State. We find no decision to the con

trary.” 261 F. 2d 521, 526.

Judge Stanley decided in our present case — as Mr. Justice

Story did in the Dartmouth College case — that the pertinent

factor is not who appoints the trustees but who controls the

corporation; and he refused to draw any inference from the

6 Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts of City

of Philadelphia, 353 U. S. 230 (1957).

13

mere fact that a minority of the Moses Cone Hospital’s pri

vate trustees are appointed by public agencies to serve the

private corporation. He then concluded that “The entire rec

ord makes it quite clear that the Cone Hospital, originally

chartered as a private corporation, is subject to no control by

any public authority, and that the appointment of the minor

ity members of its trustees by public officers and agencies has

in no way changed the private character of its business”

(208a) . The defendants submit that this conclusion is un

assailable.

(2) The ad valorem tax exemptions of the two hospitals do

not affect their character as private corporations.

The plaintiffs asserted in the District Court — and the de

fendants agreed — that the two hospitals are exempt from ad

valorem taxes assessed by the City of Greensboro and the

County of Guilford, North Carolina. No authority was cited

for the proposition that these tax exemptions in any way affect

the private character of the defendant hospitals, and the Dis

trict Court quite properly refused to draw any inference from

the fact. It is common knowledge that virtually all charitable

organizations are given tax exemptions — not only from mu

nicipal and county ad valorem taxes but from state and fed

eral taxes as well — and it can hardly be contended that all

such charitable organizations thereby become governmental

agencies. The defendant hospitals point out that the sugges

tion is refuted, at least by implication since it was necessarily

involved, in virtually all of the cases where public charities

have been held to be private corporations. Dartmouth College

v. Woodward, supra; Eaton v. Board of Managers of James

Walker Memorial Hospital, supra; Norris v. Mayor and City

Council of Baltimore, supra; Mitchell v. Boys Club of Metro

politan Police, D. C., 157 F. Supp. 101 (D* C. D. C. 1957).

14

The plaintiffs imply (they actually said in the court be

low) that tax exemption was a factor in the Burton case/ but

this clearly puts the cart before the horse. The Supreme Court

in the Burton case did point out that “ the fee is held by a tax-

exempt government agency” ; but it was unmistakably clear

that the agency was tax-exempt because it was a government

agency, and not — as the plaintiffs would have it here — that

it was a government agency because it was tax-exempt.

The District Court in Mitchell v. Boys Club of Metropoli

tan Police, D. C., supra, 108, said, with some feeling, that “ If

each time a government lends its assistance to a private institu

tion it were to acquire that institution as an arm of govern

ment, then government would indeed become a many armed

thing” ; and if the “assistance” referred to by the Court were

to include not only direct assistance but also the indirect en

couragement afforded by relief from the burdens of taxation,

then government at all levels would indeed become a monster

even more monstrous than the “many armed thing” feared

by the Court.

(3) The licensure of the two hospitals by the State of North

Carolina does not make them agencies of the State.

The plaintiffs asserted in the court below that the two de

fendant hospitals are required to be licensed by the State of

North Carolina pursuant to North Carolina General Statutes,

Section 131-126.3; and that these licenses are obtained by

application to the North Carolina Medical Care Commission

under Section 131-126.4. The District Court found, however,

that every hospital in the State of North Carolina is required

to secure such a license from the State through the Medical

Care Commission (201 a) ;8 and it is quite obvious that if such

7 Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715 (1961). See Plain

tiffs’ Brief, p. 23.

8 See also the affidavit of William F. Henderson, Executive Secretary of the

North Carolina Medical Care Commission, Appellees’ Appendix p. laa.

15

a license were sufficient to constitute a hospital a government

al agency, there could not be any such thing as a private hos

pital in the State of North Carolina.

These two sections of the North Carolina General

Statutes are short, and read as follows:

“ 131-126.3. Licensure. After July 1st, 1947, no person

or governmental unit, acting severally or jointly with any

other person or governmental unit shall establish, conduct

or maintain a hospital in this State without a license.

(1947, c. 933, s. 6.) ”

“ 131-126.4. Application for license. Licenses shall be

obtained from the Commission. Applications shall be up

on such forms and shall contain such information as the

said Commission may reasonably require, which may in

clude affirmative evidence of ability to comply with such

reasonable standards, rules and regulations as may be law

fully prescribed hereunder. (1947, c. 933, s. 6; 1949, c.

920, s. 3.) ”

It is apparent that these are regulatory sections, and that

the phrase “no person or governmental unit” becomes mean

ingless if a “person” becomes a “governmental unit”

through the mere fact of licensure; and it has been clearly

established in this Court that the mere act of the State in

licensing a private institution to carry' on its private operations

cannot cause that private institution to become a govern

mental agency. Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant,

268 F. 2d 845 (4th Cir. 1959).

“The essence of the argument is that the state licenses

restaurants to serve the public and thereby is burdened

with the positive duty to prohibit unjust discrimination in

the use and enjoyment of the facilities.

This argument fails to observe the important distinc

tion between activities that are required by the state and

16

those which are carried out by voluntary choice and with

out compulsion by the people of the state in accordance

with their own desires and social practices. Unless these

actions are performed in obedience to some positive provi

sion of state law they do not furnish a basis for the pend

ing complaint. The license laws of Virginia do not fill the

void. Section 35-26 of the Code of Virginia, 1950, makes

it unlawful for any person to operate a restaurant in the

state without an unrevoked permit from the Commission

er, who is the chief executive officer of the State Board of

Health. The statute is obviously designed to protect the

health of the community but it does not authorize state

officials to control the management of the business or to

dictate what persons shall be served.” Williams v. Howard

Johnson’s Restaurant, supra, 847.

Many if not most of the activities of the individual are

subject to regulation by government in this modern era, but

the State does not thereby adopt, or attempt to control, all of

the activities of the individual performed within the scope of

the license granted. The doctors and dentists who are plain

tiffs in this case, and the lawyers who represent them, are all

required to be licensed by the State (N. C. Gen. Stats. 90-18,

90-29, 84-4); and every automobile in North Carolina is re

quired to bear, and every driver to carry, a license from the

State (N.C.G.S. 20-50, 20-7). These are mere permits, how

ever, and not franchises, and they are available to all who wish

to and can qualify. It could hardly be contended that every

such individual, by virtue of his license, is constituted an agent

of the State performing governmental functions in exercising

his permit; and it is difficult to see how any of these situations

differs substantially from licensing a restaurant or a hospital.

It is true that no one may engage in these activities unless he

meets certain standards and secures a license from the State,

but the suggested inference “ fails to observe” that no one is

17

required to practice medicine, or dentistry, or law, or to drive

a car, or to operate a restaurant or a hospital, but that all of

these are activities “which are carried out by voluntary choice

and without compulsion by the people of the State in accord

ance with their own desires and social practices.”

It is quite clear that licensing a restaurant does not con

stitute State action. Williams v. Howard Johnsons Restau

rant, supra. It is equally clear that licensing a hospital does

not constitute State action. Eaton v. Board of Managers of

James W alker Memorial Hospital, supra.

(4) The nursing programs at the Moses Cone Hospital do not

affect the private character of that corporation.

The plaintiffs alleged in their complaint that the Moses

Cone Hospital conducts training and is regularly used as a

place of training for student nurses from the Woman’s Col

lege of the University of North Carolina and the Agricultural

& Technical College of North Carolina, both of which are tax-

supported public institutions under the laws of the State of

North Carolina; and that in the course of this training “ these

student nurses substantially contribute, without charge to the

hospital, valuable nursing services for which it would other

wise pay substantial sums” (12a). The implication and the

argument was that this constituted a contribution by the State

to the Moses Cone Hospital.

The Moses Cone Hospital then demonstrated that it does

not receive any such contribution from the student programs,

but that on the contrary it has contributed very substantially

of its funds and its facilities to the furtherance of these two

educational programs (55a, 181a, 184a, 204a). The plaintiffs

then reversed their field, and argued that because the Moses

Cone Hospital assists the State in this way, it somehow be

comes an instrumentality of the State — doing the work of the

State in the place of the State. It was to this position that

18

Judge Stanley directed his attention, and it can fairly be said

that he did not have any difficulty with it (212-13a). If con

tribution by the State does not constitute the recipient an in

strumentality of government — and the United States con

cedes that it does not (U. S. Brief, p. 19) — it can hardly be

contended that contribution to the State would make the

donor an instrumentality of government.

We are now back to midfield before this Court — and

these nursing educational programs are no longer urged either

as a contribution by the State or as a contribution to the State,

but instead now constitute a “ joint endeavor” by the hospital

and the State (Plaintiffs’ Brief, p. 36). It is truly a moving

target, but the entire arc of this pendulum of argument ig

nores the fact that both nursing programs are wholly volun

tary on both sides — between the Colleges on the one hand

and the Moses Cone Hospital on the other. The hospital has

no obligation to either of the Colleges except that which it

has voluntarily assumed; and each College uses the facilities

of the hospital to the extent, and only to the extent, that the

hospital has voluntarily agreed it may use them. Neither Col

lege in any way controls or directs the policies or the opera

tions of the hospital; and the hospital, on the other hand, does

not in any way control or direct any facet of these nursing

educational programs (212-13a).

It seems perfectly clear that the Woman’s College of the

University of North Carolina and the Agricultural & Techni

cal College of North Carolina are agencies of the State, and

that their nursing educational programs are State activities.

But those activities are completely controlled by the Colleges

— the State has not “ delegated” or “ authorized” or “ acqui

esced in” the exercise of its educational function by the Moses

Cone Hospital (See Plaintiffs’ Brief, p. 22, n. 30) — and it

hardly seems reasonable to suggest that because the hospital

permits a portion of those activities to be carried on under the

19

control of the Colleges in its facilities, or that because the hos

pital contributes funds to the furtherance of those activities,

it thereby becomes an agency of the State.

(5) The grants of Hill-Burton funds to the two hospitals do

not make them instrumentalities either of the Federal

government or of the State.

The Moses Cone Hospital and the Wesley Long Hospital

have both received Federal funds under the Hill-Burton Act9

in aid of their construction and expansion programs, and these

funds were allocated to these hospitals by the North Carolina

Medical Care Commission, an agency of the State of North

Carolina (213-14a) .

Whether the Federal government should contribute funds

to a segregated private facility is one question — whether of

ethics, of morality, of policy, or simply of politics; and whether

the Federal government can constitutionally contribute funds

to a segregated private facility — under the Hill-Burton or

under any other Act — is another question;10 and both ques

tions would appear to be equally irrelevant to our present in

quiry. For the appellants in this action do not seek to prevent

the contribution of funds under the Hill-Burton Act. They

suggest instead that the Hill-Burton Act is unconstitutional,

and that because it is, the contribution of funds to a private

facility under the Act (even though made and accepted on

definite and clearly understood conditions) nonetheless some

how infects that facility with a loss of its privacy and private

character, and makes it instead an instrumentality of the Fed

eral government subject to the inhibitions of the Fifth Amend

ment — and because the allocation of Federal funds is made

through the Medical Care Commission, makes it an instru

mentality of the State as well subject to the inhibitions of the

9 Title 42, United States Code, Sec. 291 et seq.

The Attorney General says that it can (U. S. Brief, p. 39).10

20

Fourteenth Amendment.

It is quite clear that this is not the law. “ It is well settled

that aid given by a government to a private corporation is not

enough in itself to change the character of the corporation

from private to public.” Mitchell v. Boys Club of Metropoli

tan Police, D. C., supra, 107. The Attorney General concurs:

“Nor do we urge that the receipt of government financial aid

is sufficient, without more, to deprive an otherwise private

institution of its non-governmental character.” (U. S. Brief,

p. 19) . It is equally clear (and particularly in this Circuit)

that government control — and not government contribution,

whether direct or indirect — is the decisive factor in the deter

mination of whether a corporation is public or private. Eaton

v. Board of Managers of James Walker Memorial Hospital,

supra; Norris v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, supra;

Mitchell v. Boys Club of Metropolitan Police, D. C., supra.

The Federal government would indeed be a “ many armed

thing” if it acquired every private organization to which it

contributes — and it surely cannot be argued that it acquires

only those organizations to which it contributes unconstitu

tionally, and not those to which it contributes properly. Con

tribution by government — whether constitutionally made

or improperly made — is contribution still, and nothing more.

In the Eaton case, the City of Wilmington and the County

of New Flanover had contributed funds to the James Walker

Memorial Flospital for many years under State legislation

which was subsequently held unconstitutional under the

North Carolina Constitution. Thus all of these contributions

were unconstitutionally made. But control — and not contri

bution — is the decisive factor; and this Court looked to con

trol, and held that the James Walker Memorial Hospital “was

not an instrumentality of the State but a corporation man

aged and operated by an independent board free from State

control.” 261 F. 2d 521, 525.

21

The provisions of the Hill-Burton Act have had recent

consideration by the Supreme Court of Appeals of the Com

monwealth of Virginia in Khoury v. Community Memorial

Hospital, Inc., 203 Va. 236, 123 S.E. 2d 533 (1962). The

hospital there was a non-stock, non-profit corporation char

tered under the laws of Virginia to establish, construct, and

maintain a regional hospital, and somewhat more than half

of its construction funds had been contributed by the Fed

eral government under the Hill-Burton Act, another portion

had been contributed by the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

the balance had been provided by local subscriptions. The

management of the hospital was vested in a self-perpetuating

board of trustees.

The Virginia Court had these things to say:

“We next turn to the question of whether the use of

federal and state funds for construction thereby consti

tuted the hospital a public corporation.

“The distinctions between a public and a private cor

poration have been so carefully drawn and so long recog

nized that we experience no difficulty in answering the

question in the negative.”

[The Court then cited, and quoted from, the Dart

mouth College case.]

“The hospital is not owned by the federal or the state

government, albeit federal and state funds may have made

its construction possible. It is not an instrumentality of

government for the administration of any public duty, al

though the service it performs is in the public interest. Its

officers are not appointed by and are not representatives

of government, notwithstanding that their authority stems

from legislative enactments. Under these circumstances,

the hospital falls squarely within the time-honored defi

nition of a private corporation.”

22

# # #

“The hospital was established pursuant to a charter,

granted by the Commonwealth, conferring upon its public

spirited organizers the right and authority to operate as a

private corporation. That charter is a contract between

the state and the incorporators. One of the unwritten

provisions of that contract is that the trustees of the cor

poration shall have the right to conduct its affairs as they

might, in their sound discretion, see fit. Inherent in the

charter is the understanding that, except as provided by

law, the state will not interfere in the corporation’s inter

nal affairs.”

Control and not contribution is the decisive factor, and

the mere contribution of Federal funds under the Hill-Burton

Act therefore clearly cannot change the character of a recipi

ent from private to public, or constitute that private recipient

an agency of the Federal government; and a fortiori the mere

fact that the Federal funds were allocated to the private re

cipient through a State agency cannot constitute that private

recipient an agency of the State. The private corporations

clearly remain private despite the contributions, and the

Fourteenth and the Fifth Amendments erect no shield against

their “ merely private conduct, however discriminatory or

wrongful.” Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. T 13 (1948).

(6) Neither the Federal government nor the State exercises

any control over the two hospitals through the Hill-

Burton Act.

The appellants have apparently come to agree—with Judge

Stanley and with the decided cases — that control, and not

contribution, is the decisive factor in determining whether a

corporation is a private one or a public one in the constitu

tional sense, for in this Court the Hill-Burton program has

now become “ the Hill-Burton hospital system,” a misnomer

23

implying a continuing supervision which the Act itself ex

plicitly disclaims.

The Hill-Burton Act does not provide for the construction

of hospitals by the Federal government or by the States, but

simply undertakes “ to assist in the construction of public and

other nonprofit hospitals.” 42 U. S. C. Sec. 291 (b ). Yet the

appellants are apparently contending that when a private hos

pital accepts Hill-Burton funds in aid of its own construction

program, it is thereafter assuming to act for the State in “per

forming an essential governmental function” (Plaintiff’s Brief,

p. 29), and “ that such a non-governmental institution be

comes pro tanto a State instrumentality with concomitant

obligations” (U. S. Brief, p. 20). This contention, however,

ignores the fact that the only logical conclusion to be drawn

from these illogical premises is that a private hospital which

does not receive any financial aid at all from government, is

shouldering the assumed burden “pro even more tanto” — so

that under this reasoning, the more private it is, the more

public it would become.

It is difficult to see why this reasoning should apply to

hospitals when it does not apply to other fields which suggest

it much more strongly. The State has actually undertaken to

provide educational opportunity for its citizens, for example

— a true commitment; and it is simply underlining the obvious

to point out that Duke University (like Dartmouth College),

by its mere existence, lightens the burden of that commitment

“ pro tanto.” Yet Duke University (like Dartmouth College)

was privately endowed and is privately controlled; it has joined

no State “ system” ; and (like Dartmouth College) it is clearly

a private institution, and not an instrumentality of

government.

The Hill-Burton Act, as we have seen, does not require

the State to construct hospitals, and while the State may be

interested in fostering the development of adequate facilities,

24

it has made no commitment to hospital care as it has to edu

cation. A private hospital (like a private college) may be do

ing something useful and generally approved whether or not

it has received Federal or State funds, but it enjoys no fran

chise or monopoly, and it is quite obvious that it is not shoul

dering any burden for the State or relieving the State of any

legal obligation and that such a private hospital “ is not an in

strumentality of government for the administration of any

public duty, although the service it performs is in the public

interest.” Khoury v. Community Memorial Hospital, Inc.,

supra, 123 S. E. 2d 533, 538. The Attorney General here

does not attack the “ rule” — and the word is his — “ that an

otherwise private institution is not subject to the nondiscrimi

nation provisions of the Constitution merely because . . . it is

generally open to the public” (U. S. Brief, p. 19); and Mr.

Justice Story pointed out in 1819 the danger of assuming

“ that because the charity is public the corporation is public”

and emphasized specifically that “A hospital founded by a pri

vate benefactor is, in point of law, a private corporation,

although dedicated by its charter to general charity.” Dart

mouth College v. Woodward, supra, 671, 669.

The popular name of the Hill-Burton Act — given it by the

Congress — is the “ Hospital Survey and Construction Act.”

The declared purpose of the Act is to assist in the inventory

of existing facilities, “ to assist in the construction of public

and other nonprofit hospitals,” and to authorize research and

experiment for the effective development and utilization of

services and facilities (42 U.S.C. 291) ; and it is again appar

ent (as in the case of the North Carolina Hospital Licensing

Act) that if the assistance rendered a private nonprofit hos

pital under the Act makes that hospital a public one, the

phrase “public and other nonprofit hospitals” becomes

meaningless.11

11 The Attorney General doffs his cap to this suggestion. U. S. Brief, p. 28.

25

If there is a “ Hill-Burton hospital system” — as the ap

pellants suggest — it is a truly secret society, for while many

“public and other nonprofit hospitals” have applied and quali

fied for Hill-Burton funds, no instance is cited where any hos

pital has either joined the “ system” or been drafted into it

without receiving a grant-in-aid. The parties agreed in the

court below — and Judge Stanley found — “ that the Hill-

Burton funds received by the defendant hospitals should be

considered as unrestricted funds” (214-15a); and it is evident

that they were unrestricted except for the minor limitations on

and conditions of the grants-in-aid. And we have already seen

(and the United States has agreed) that the receipt of gov

ernmental aid is not “ sufficient, without more, to deprive an

otherwise private institution of its non-governmental charac

ter.” (U. S. Brief, p. 19) .

The United States has also virtually conceded that the

Hill-Burton Act does simply establish a program of grants-in-

aid (U. S. Brief, p. 29, and n. 20); and indeed this virtual

concession would appear virtually inescapable, for in addition

to the portions of legislative history cited by the Attorney

General, the following colloquy took place at the hearings on

the Bill before the Senate Committee on Education and

Labor:

“ Senator Taft. Dr. Smelzer, as I understand it, and as

the Surgeon General says, there shall be so many dollars,

$100,000,000; say $5,000,000 allotted to the State of

Ohio, that in Ohio, say, the Federal grant will be 50 per

cent, then any private hospital can apply for that grant.

Dr. Smelzer. Yes, sir.

Senator Taft. And then the Surgeon General may

grant that Federal grant directly, we will say, for the en

largement of the private hospital, and when that money is

gone that is owned by the private hospital, is it not?

26

Dr. Smelzer. Yes, sir.

Senator Taft. It is a gift for that particular private

hospital.

Dr. Smelzer. Yes, sir.”

(Hearings before the Senate Committee on Education

and Labor on S. 191, 79th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 22).

It should be remembered—in considering all of the “ re

quirements” of the Hill-Burton Act which are detailed by the

appellants — that the Hill-Burton Act does not actually “ re

quire” anything of anyone, for no hospital is required to ac

cept Hill-Burton funds. The appellants fail—in the words of

this Court—“to observe the important distinction between ac

tivities that are required by the state and those which are car

ried out by voluntary choice and without compulsion by the

people of the state in accordance with their own desires and

social practices.” Williams v. Howard Johnsons Restaurant,

supra, 847. All of the so-called “ requirements” of the Hill-

Burton Act are purely and simply “conditions of the grant”

to be accepted or rejected voluntarily by a private non-profit

hospital. If it wants the money, then the hospital accepts the

conditions of the grant; but this is a “voluntary choice” made

“without compulsion” and not obedience to mandate; nor is

it an abject surrender of privacy, but instead a simple accept

ance of agreed conditions in clearly-defined areas of agree

ment.

It should also be noted that the Hill-Burton Act does not

in any way “ authorize” or “ sanction” discrimination, and that

it does not say affirmatively to any hospital that it may dis

criminate. It does require — as a condition of the grant of

Federal funds — that the State plan (if the State wishes to

participate) shall provide for adequate hospital facilities

“without discrimination.” It further provides that the Sur

geon General “ may” by regulation require of any applicant

27

hospital — if such hospital wants a grant of funds — an assur

ance that there will be no discrimination; and the Act then

provides that under certain circumstances, the Surgeon Gen

eral shall waive this assurance of non-discrimination which he

was not required to exact from the applicant to begin with.

42 U. S. C. Sec. 291e ( f ) .

Nowhere, however, does the Hill-Burton Act “authorize”

or “ sanction” or even “affirmatively permit” discrimination.

At most, it simply provides that in the stipulated circum

stances the assurances of non-discrimination normally exacted

as conditions of the grant shall be waived, so that the appli

cant under these stipulated circumstances may qualify for

Hill-Burton funds without agreeing to any limitations of (and

quite obviously without receiving any dispensations to en

large) its otherwise lawful conduct in this area. And finally,

even when the assurances of non-discrimination are not

waived but are exacted as conditions of the grant of funds,

those assurances relate wholly and solely to non-discrimination

in the admission of patients; the Act does not deal in any way

or to any extent (even as a condition of the grant) with the

matter of staff admissions.

It should be abundantly clear that all of the “ require

ments” of the Hill-Burton Act are purely and simply condi

tions of the grant of funds, for the Act itself — as the Vir

ginia Court in the Khoury case pointed out — expressly dis

claims any Federal control over the hospitals to which Federal

funds are contributed under the Act. Title 42, United States

Code, Section 291m provides as follows:

“ 291m. State control of agencies

Except as otherwise specifically provided, nothing in

this subchapter shall be construed as conferring on any

Federal officer or employee the right to exercise any super

vision or control over the administration, personnel, main-

2 8

tenance, or operation of any hospital, diagnostic or treat

ment center, rehabilitation facility, or nursing home with

respect to which any funds have been or may be expended

under this subchapter.”

The appellants have apparently had some difficulty with

Section 291m, which they have attempted to alleviate by

suggesting here that the Federal government does exercise

control but does so through the State agency. This sugges

tion, however, ignores the fact established in the court below

that The North Carolina Medical Care Commission (which

is the relevant agency of the State) disclaims any authority,

and makes no attempt, to exercise any supervision or control

over the administration, personnel, maintenance, or operation

of any hospital licensed by it under the North Carolina Hos

pital Licensing Act, whether such hospital has received or has

not received Hill-Burton funds; and that the Attorney Gen

eral of the State of North Carolina has ruled that The North

Carolina Medical Care Commission has no such authority.12

Judge Stanley concluded below that “no state or federal

agency has the right to exercise any supervision or control

over the operation of either hospital by virtue of their use of

Hill-Burton funds, other than factors relating to the sound

construction and equipment of the facilities, and inspections

to insure the maintenance of proper health standards.” (217a).

In the face of Section 291m and the unequivocal position of

The North Carolina Medical Care Commission and the Attor

ney General of the State of North Carolina, it is difficult to

see how this conclusion can be challenged.

;(7) The whole is no greater than the sum of the parts

The defendants did contend in the court below that each

12 See the affidavit of William F„ Henderson, Executive Secretary of The North

Carolina Medical Care Commission, and the Opinion of the Attorney Gen

eral of the State of North Carolina dated 10 February 1962 and filed below

with that affidavit, both of which are printed herewith, Appendix, p. laa. It

may be significant that in printing their voluminous appendix of 225 pages,

the appellants omitted to bring forward these particular documents.

2 9

of these points of contact of the two hospitals with govern

ment which were suggested by the plaintiffs is insignificant in

itself — and that the whole could be no greater than the sum

of the parts (218a). The plaintiffs, on the other hand, seemed

to feel that some magic in the phrase “ totality of govern

mental involvement” could abrogate both mathematics and

common sense so that five times zero would equal five and not

zero; and as Judge Stanley indicated, they cut this wand from

the Burton case (217a) .13

It might be pointed out initially that the points of con

tact in the Burton case were far more numerous and far more

substantial than anything which has even been suggested here

—the restaurant in Burton, simply for a starter, was a lessee in

a building owned, operated, heated, and structurally main

tained by the Wilmington Parking Authority, a tax-exempt

government agency — and Judge Gewin’s careful analysis of

the Burton case in his dissenting opinion in Hampton v. City

of Jacksonville1,1 makes this abundantly clear, by weight and

by measure. But it is hardly necessary to sift these points of

contact straw by straw, for the Burton case, by its own defini

tion, is purely and simply a leasing case, a recognized category

of cases adverted to by Judge Stanley below (217-18a), by the

Attorney General here (U. S. Brief, p. 17, n. 10), and by Mr.

Justice Clark for the majority (there were three dissents) in

the case itself when he carefully limited his holding to the

specific facts of the case:

“ Because readily applicable formulae may not be fash

ioned, the conclusions drawn from the facts and circum

stances of this record are by no means declared as uni

versal truths on the basis of which every state leasing

agreement is to be tested. * * * Specifically defining the

limits of our inquiry, what we hold today is that when a

13 Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715 (1961).

14 304 F. 2d 320 (5th Cir. 1962), cert. den. sub nom. Ghioto v. Hampton,

9 L. Ed. 2d 170.

3 0

State leases public property in the manner and for the

purpose shown to have been the case here, the proscrip

tions of the Fourteenth Amendment must be complied

with by the lessee as certainly as though they were bind

ing covenants written into the agreement itself.” Burton

v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 725-6

(1961). Compare Harrison v. Murphy, 205 F. Supp. 449

(D. C. Del. 1962).

The plaintiffs also now rely in this Court on Hampton v.

City of Jacksonville which found State action where two city-

owned golf courses were conveyed to purchasers subject to a

possibility of reverter if the properties were not forever used as

golf courses. Judge Gewin wrote a strong and well-reasoned

dissent: Judge Jones concurred specially on the sole ground

that the reverter clause was calculated and “ intended” by the

City to effect discrimination; and the case therefore rests on

Chief Judge Tuttle’s theory that a possibility of reverter as

sures “ complete present control.” 304 F. 2d 320, 322. This

position not only deliberately refuses to accept the holding of

the Eaton case — which has flatly ruled on the same problem

in this Circuit — but (as Judge Gewin points out) also ignores

the reasoning of that case. In the Eaton case, Judge Gilliam

pointed out in the District Court that “The only way the City

and County can claim an interest in the property or any con

trol over the property would be in the event that the hospital

ceased to be used for the care of the sick and afflicted of New

Hanover County. The purpose and effect of the deed is to

carry out the intent of the charter to create a public charity

but not a public corporation. The City and County may

eventually regain the property, but this possibility is distinctly

within the control of the hospital corporation. Only the latter

possesses initiative with regard to the same” 164 F. Supp.

191, 197; and this Court approved that reasoning, and found

that the hospital was “ free from State control.”

31

The defendants submit that reason lies with Eaton, and

that a possibility of reverter is far from tantamount to “com

plete present control” ; but in any event, it is evident that the

problem does not exist in our present case and that neither

the Burton case nor the Hampton case is analogous, for the

Moses Cone Hospital does not lease from the State and the

State has no possibility of reverter in its property. Instead —

as Judge Stanley found — “The Cone Hospital owns, and has

owned since 1911, the fee simple title to the real property on

which its hospital is located. Its Board of Trustees has the ex

clusive power and control over all real and personal property

of the corporation, and all the institutional services and activi

ties of the hospital” (200a).

The plaintiffs suggest that the right of the United States

to recover its Hill-Burton contribution if within twenty years

after the completion of construction the owner of the facility

shall cease to be “non-profit” (or if the facility shall be trans

ferred to an unqualified transferee) is similar to a possibility

of reverter; but this is remoteness compounded. Reversion

takes effect by operation of law; these provisions merely con

fer a right which may or may not be enforced. Under a pos

sibility of reverter, the property itself reverts; the right pro

vided here is for a monetary recovery, and there is no provi

sion for the recovery of any interest in the facility itself. It

seems apparent that this right of recovery is simply another

condition of the grant of funds, but even a possibility of re

verter is not tantamount to “complete present control” ; and

this right of recovery in any event is at least one step further

removed, for it is clearly not tantamount to a possibility of

reverter.

This case has been argued differently, of course, but ex

cept for the “power and prestige” of the Attorney General

and the voluntary cooperation of the Moses Cone Hospital in

the nursing educational programs of the two colleges, there is

32

no single point of contact here which is not to be found in

the Eaton case, (including Federal money); and conversely

and to put this case well within the Eaton case, there were a

number of additional contacts in Eaton which are not to be

found here (e.g., the possibility of reverter, the City and

County contributions, and the majority of the Board of Man

agers) . It is submitted that the Eaton case does control our

present case; that its reasoning is still wholly valid; and that —

on precedent and on reason — it requires the affirmance of

the District Court.

(8) In reference to the position of the American Civil Liber

ties Union

Discrimination by private persons is not itself violative of

the Fourteenth Amendment. It is therefore difficult to credit

as a serious one the suggestion that the mere omission of the

State to make illegal this permissible conduct is violative of

the same Fourteenth Amendment — that all under the one

amendment the State commits a crime in failing to make a

crime of that which is admittedly not a crime.

(9) In reference to the two individual defendants

The plaintiffs did not allege any specific grievances against

the two individual defendants, or request any specific relief

against them. It is difficult to see why they were joined in this

action at all, but it is apparent in any event that they were

joined in their respective capacities as Director and as Admin

istrator of the two hospitals; that their involvement is wholly

derivative; and that they are even more clearly behind the

shield which protects the two private corporations in this ac

tion from any offense against constitutional guarantees

through their purely private actions. If a corporation is a pri

vate one, and not an instrumentality of government, either

State or Federal, it follows inevitably that an individual act

ing for that private corporation—and once removed—cannot

33

be an agent of government, either State or Federal, in so act

ing; and that the Fourteenth and the Fifth Amendments

“erect no shield against (his) merely private conduct.”

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 13 (1948); Watkins v. Oak-

lawn Jockey Club, 183 F. 2d 440 (8th Cir. 1950).

III. THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE CHALLENGED

PROVISIONS OF THE HILL-BURTON ACT IS IRRELE

VANT AND IS NOT BEFORE THE COURT IN THIS

ACTION.

The plaintiffs asserted in the court below that the so-called

“ separate but equal exception” of Section 291e (f) of the Hill-

Burton Act is unconstitutional. The Attorney General of the

United States intervened in the action, and said that he too

thought these provisions were unconstitutional. The defend

ants have always maintained that the constitutionality of

these provisions is completely and wholly irrelevant in this

action; and Judge Stanley agreed that the question of con

stitutionality is not an issue in this case (220a).

It is true, as the plaintiffs note (Plaintiffs’ Brief, p. 40, n.

53), that the defendants do not rely on the separate but equal

provisions of the Plill-Burton Act to excuse their conduct —

not because such an argument is preposterous (even if it is

preposterous) but simply because it is irrelevant. The defend

ant hospitals do agree, however, that if they were public cor

porations in the constitutional sense — or if one prefers, if

their contacts with government were such that they were sub

ject to the constitutional amendments — it would be prepos

terous to suggest that the provisions of the Hill-Burton Act or

of the Surgeon General’s regulations could possibly excuse un

constitutional conduct on their part; but this merely empha

sizes again the entire irrelevance of the question of the con

stitutionality of the Hill-Burton provisions.

The defendants have pointed out again and again that the

3 4

significant question — and the only significant question — in

this case is whether these defendant hospitals are govern

mental instrumentalities or private corporations. If they are

instrumentalities of government, then they are subject to the

constitutional amendments and discrimination is unlawful

under those amendments; and the provisions of the Hill-

Burton Act can neither authorize nor excuse violations of the

constitutional amendments. But if these hospitals are private

corporations, they are not subject to the amendments; the

Federal courts do not even have jurisdiction to consider the

matter of discrimination; and the defendant hospitals need no

charter, no license, and no apology, or if you will, no “ authori

zation,” no “ sanction,” and no “permission” — whether from

the provisions of the Hill-Burton Act or from any other

source — for their purely private conduct. Either way, how

ever, public or private, the constitutionality or unconstitu

tionality of the Hill-Burton provisions cannot possibly affect

the result, and it is therefore quite apparent that the consti

tutionality of these provisions is not relevant in the present

action or before this Court for consideration. The defend

ants cannot concede (since the issue is not involved), but

would be entirely willing to assume for the purposes of argu

ment, that the challenged provisions of the Hill-Burton Act

are unconstitutional. It is an assumption of no moment, for

the defendant hospitals are private corporations still and their

conduct is private conduct, and the constitutional amend

ments “ erect no shield against merely private conduct.”

The Hill-Burton contracts between the Federal govern

ment and these two private hospitals are executed contracts;

and the only significance of the separate but equal provisions

of the Hill-Burton Act in our present case is to establish that

these private hospitals — in accepting Hill-Burton funds —

did not agree to any limitations on their lawful private con

duct in this area, but that on the contrary, they had an express

35

understanding with the Federal government when they ac

cepted the funds that they would retain their private charac

ter and their freedom of action in the precise area which is

under challenge here.

The United States has said (in its brief, at page 41) that

“ It was the underlying federal statute (the Hill-Burton Act)

which unquestionably led to the North Carolina program of

hospital construction and which instigated the discrimina

tions which this action seeks to enjoin.” This is a sweeping

and wholly implausible generalization. It does not appear in

our record, for it did not appear relevant until we began to

speculate about instigation, but it is a matter of ascertainable

fact that at the last annual audit report at September 30,

1962, the Moses Cone Hospital trust fund (which was estab

lished wholly through private endowment except for the Hill-

Burton contribution) showed total assets of $14,242,594.

These assets, at this value, included the hospital land at a

value of $1.00; buildings and other physical assets at depreci

ated cost (the accumulated reserve for depreciation of physi

cal assets of $2,039,327 already greatly exceeded the total

Federal contribution of $1,269,950 under the Hill-Burton

A ct); and 492,025 shares of the common stock of Cone Mills

Corporation at a nominal total value of $3.00 — the current

market value of the stock is approximately $12,00 per share.

The Federal government is concededly a larger operation than

the Moses Cone Hospital trust, but it is nonetheless quite

obvious that the trust fund was entirely adequate and clearly

charged with the obligation to build and operate the hospital

in accordance with the purposes of the trust — regardless of

aid or “ instigation” from the “ underlying federal statute.” It

is therefore something less than plausible to suppose — if we