Dobbins v. Virginia Reply Brief on Behalf of Plaintiff in Error

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dobbins v. Virginia Reply Brief on Behalf of Plaintiff in Error, 1957. 900b07fb-af9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c8b278dc-f9b1-4617-a5e4-e0af84a623ab/dobbins-v-virginia-reply-brief-on-behalf-of-plaintiff-in-error. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

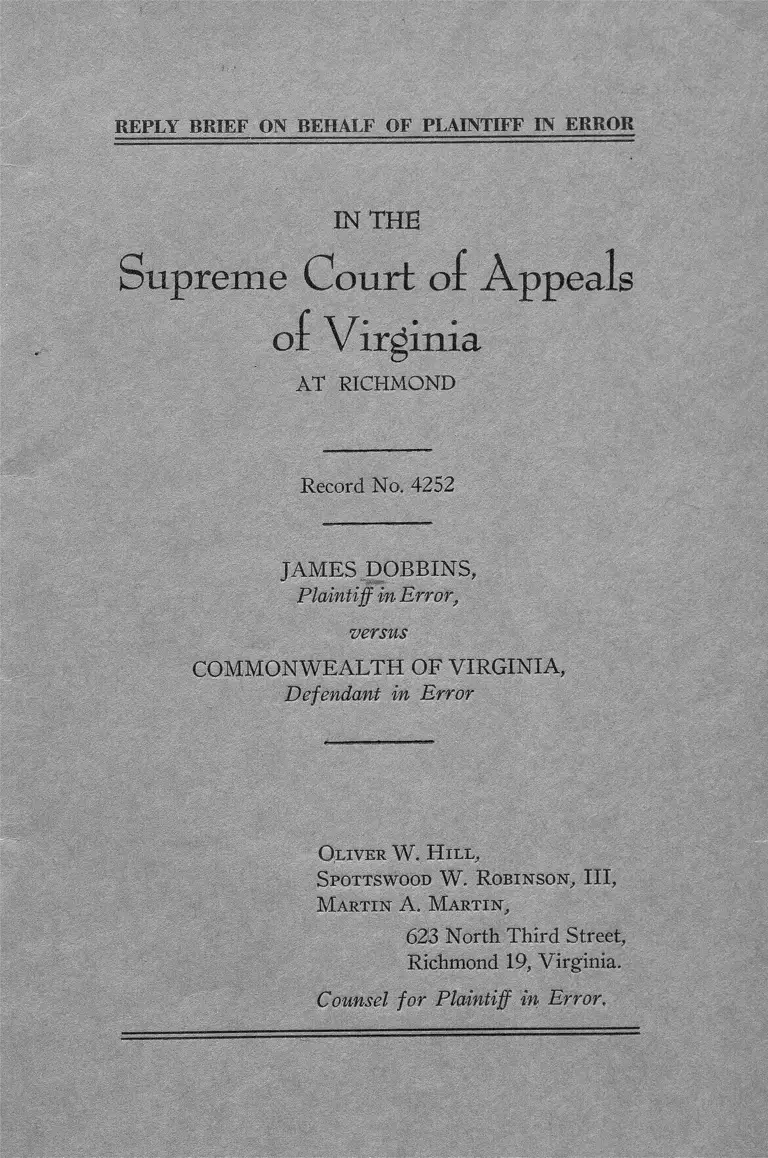

REPLY BRIEF ON BEHALF OF PLAINTIFF IN ERROR

IN THE

Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia

AT RICHMOND

Record No. 4252

JAM ES DOBBIN S,

Plaintiff in Error,

versus

C O M M O N W E A L TH OF V IR G IN IA ,

Defendant in Error

Oliver W . H ill,

Spottswood W . Robinson, III,

Martin A. Martin,

623 North Third Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia.

Counsel for Plaintiff in Error,

SUBJECT IN D E X

Preliminary Statement................................................... 1

Questions Not Involved in the Appeal ..................... 2

Argument ......................................................................... 3

I. The Elements of Racial Segregation and Dis

crimination Consequent upon Attendance of

Defendant’s Child at Hamilton-Holmes

High School Are Relevant and Material to

the Issues Involved ......................................... 3

II. The Elements of Racial Segregation and Dis

crimination Consequent upon Attendance of

Defendant’s Child at Hamilton-Holmes

High School Are Available in Defense

Against the Prosecution in This C ase........ 6

A. The Poulos Case ...................................... 7

The New Hampshire Proceedings ........ 8

The Supreme Court Proceedings .......... 10

Conclusions as to the D ecision................. 15

B. Other Cases ............................................... 19

Conclusion ................................................................ 26

T A B L E O F C ITA TIO N S

Cases

Campbell v. Bryant, 104 Va. 509, 52 S.E. 638

(1905) ............................................ 20

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940) 10, 14, 20

Carpel v. Richmond, 162 Va. 833, 175 S.E. 316

(1934)

Page

6

Chicot County District v. Baxter State Bank, 308

U.S. 371 (1940) ........................................................ 20

Dahnke-Walker Milling Co. v. Bondurant, 257 U.S.

282 (1921) ................................................................ 5

Dejonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353 (1936) ............20,21

Estep v. United States, 327 U.S. 114 (1 9 4 6 ) ............ 10

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U.S. 147 (1948) ..................... 19

Foster v. Commonwealth, (Record No. 2747, Oc

tober, 1943, Term, Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia, Unreported) ...................................... 5, 20, 2J

Gibson v. United States, 329 U.S. 338 (1946) ........ 10

Griffin v. Norfolk County, 170 Va. 370, 196 S.E.

698 (1938) ................................................................... 6

Hague v. Congress of Industrial Organizations, 307

U.S. 496 (1939) ........................................................ 10

Jones v. County School Board of Brunswick County,

(Record No. 4090, October, 1952, Term, Unre

ported) ................. 18

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) ....................... 5

Louthan v. Commonwealth, 79 Va. 196 (1884) ... 20, 21

Miller v. Commonwealth, 88 Va. 618, 14 S.E. 161

(1892) ....................................................................... 20,21

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 (1946) ............ 20,21

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (1 9 5 1 ) ............ 5

Norton v. Shelby County, 118 U.S. 425 (1886) ........ 19

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925) ... 5

Poindexter v. Greenhow, 114 U.S. 270 (1885) ......5,23

Porter v. Commonwealth, (Record No. 2746, Oc

tober, 1943, Term, Supreme Court o f Appeals of

Virginia, Unreported) .......................................5,20,21

Page

Poulos v. New Plampshire, 345 U.S. 395

(1953) ...........................7,8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15,24,25

Poulos v. State, 97 N. H. 352, 88 A. 2d 860

(1952) ......................................................................... 9,10

Quong W ing v. Kirdendall, 223 U.S. 59 (1912) ...... 5

Richmond v. Deans, 281 U.S. 704 (1930) ................. 5

Royall v. Virginia, 116 U.S. 572 (1886) ... 5, 14, 20, 21

23, 25

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ..................... 5

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948) ... 19

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) ................ 5

Snyder v. Massachusetts, 291 U.S. 97 (1934) ........ 5

State v. Derrickson, 97 N. H. 91, 81 A. 2d 312

(1951) ......................................................................... 8

State v. Poulos, 97 N. H. 91, 81 A. 2d 312 (1 9 5 1 )... 8

State v. Stevens, 78 N. H. 268, 99 A. 723, L. R. A.

1917C, 528 (1916) ................................................... 9

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516 (1945) ................ 14, 20

C O N ST IT U T IO N A L A N D S T A T U T O R Y

A U T H O R IT IE S

Constitution of the United States:

Page

First Amendment................................................... 12

Fourteenth Amendment..................................5, 10, 17

United States Code:

Title 8, Section 41 ............................................... 5

Code of Virginia (1950) :

Section 22-57 17

IN THE

Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virg inia

AT RICHMOND

Record No. 4252

JAM ES D OBBIN S,

Plaintiff in Errorr

versus

C O M M O N W E A L TH OF V IR G IN IA ,

Defendant in Error

REPLY BRIEF ON BEHALF OF PLAINTIFF IN ERROR

P R E L IM IN A R Y STA TE M E N T

The Commonwealth’s brief presents certain arguments

which plaintiff in error desires to answer. Hence this

reply brief.

Plaintiff in error will hereinafter be referred to as

the defendant, the position he occupied in the trial court.

References to the record, and to the petition for writ of

error, adopted as and hereinafter referred to as defend

ant’s opening brief, are to the page numbers printed in the

upper left and right corners of the page rather than to

the original page numbers. A statement of the material

proceedings in the lower court, the errors assigned, the

questions involved in the appeal, a statement of the facts,

and defendant’s opening argument, are contained in de

fendant’s opening brief.

Q U ESTIO N S N O T IN V O L V E D IN T H E A P P E A L

The Commonwealth addresses argument to three ques

tions which may be eliminated at the outset because they

are not involved in this appeal.

It argues that the compulsory attendance laws are valid

on their face (Commonwealth’s Brief, pp. 6, 7). De

fendant does not contend that the invalidity o f such laws,

as to him, appears on their face. As was stated in his

opening brief (pp. 8-9), he claims no immunity to such

laws when so enforced as to affect all similarly situated

persons in substantially the same manner. He does com

plain that such laws, as here enforced, produce dissimilar

effects upon a group o f children and parents, including

himself, differentiated from others only by race. He does

contend that upon the facts and in the circumstances

shown by the evidence received and the evidence tendered

in this case, such laws cannot constitutionally be en

forced against him. And he further contends that these

laws, properly construed with reference to the facts and

circumstances of this case, were never violated by him.

The Commonwealth further argues that the reasons for

nonattendance specified in the compulsory attendance

laws are exclusive (Commonwealth’s Brief, pp. 18-21).

Defendant does not contend that there are nonstatutory

[ 3 ]

justifications for nonattendance in cases where the laws

have valid and proper operation. Defendant does contend

that he is not confined to statutory justifications where,

as here, the statutes neither validly nor properly apply

to him.

Additionally, the Commonwealth argues that defend

ant’s beliefs do not exempt him from compliance with

the compulsory attendance laws (Commonwealth’s Brief,

pp. 7, 15-19, 24). Defendant has never contended that

beliefs, as such, do. Defendant claims exemption because

the laws can neither constitutionally nor properly be

applied or enforced against him upon the facts and cir

cumstances of this case.

A R G U M E N T

I

The Elements of Racial Segregation and Discrimination

Consequent upon Attendance o f Defendant's Child at

Hamilton-Holmes High School are Relevant and Ma

terial to: the Issues Involved.

The Commonwealth urges that considerations o f racial

segregation and discrimination— necessary concommit-

ants of defendant’s child’s attendance at Hamilton-

Holmes High School— are irrelevant (Commonwealth’s

Brief, pp. 13-15, 21-22, 25, 30). On this basis, it further

contends that defendant’s evidence offered at the trial

upon these matters was properly held to be inadmissible

on the merits of the case. (Commonwealth’s Brief, pp.

22-24.)

While this case is necessarily based upon an alleged

violation of the compulsory attendance laws, it is clear

[ 4 ]

that their invalidity, as applied to the situation presented

in the instant case, arises from their operation integrally

with the segregation laws and upon the differentials

developing as between attendance at West Point High

School and attendance at Hamilton-Holmes High

School. This was extensively discussed in defendant’s

opening brief (pp. 7-10). As was there pointed out, the

conviction in this case did not follow a refusal by de

fendant to send his child to West Point High, where the

Town’s white secondary students attend, but resulted

because defendant refused to send the child to Hamilton-

Holmes (1 ) the students in which are kept apart from

all other racial groups in the Town, (2 ) which is unequal

and inferior to West Point High, (3 ) which is owned

and controlled by an entirely different governmental

agency, and (4 ) attendance at which would subject all

Negro parents and children to burdens and hardships to

which white parents and children are not subjected. The

compulsory attendance laws, as here applied, would com

pel the child to attend Hamilton-Holmes and compel the

parent to send her there, and this solely because of their

race and color.

The Commonwealth fails to appreciate these considera

tions. Indeed, it twice undertakes to restate defendant’s

contentions upon this appeal (Commonwealth’s Brief,

pp. 2, 9 ). Neither restatement is acceptable to defend

ant. His position, insofar as the constitutional validity

of the compulsory attendance laws is concerned, is that

the application or enforcement o f such laws to require

defendant to send his child to attend, or to require the

child to attend, (1 ) a racially segregated school, or (2 )

a school inferior to the school attended by similarly

situated white children, or (3 ) a school attendance at

[ 5 ]

which would subject defendant and the child to burdens

and inconveniences to which white parents and their

children are not subjected, or (4 ) a school over which the

School Board of West Point Town has no jurisdiction or

control, denies rights of both defendant and the child

secured by the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States, and by Title 8, United States Code, Sec

tion 41, and accordingly is unconstitutional and void.

As defendant pointed out in his opening brief (pp.

9-10), this challenge is not confined to segregation laws,

but extends to any other type of state law or action ac

complishing the same results. Defendant repeats that

constitutional protections extend to “ sophisticated as

well as simple-minded modes of discrimination,” Lane v.

Wilson 307 U.S. 268, 275; see also Smith v. Allwright,

321 U.S. 649 (1944) ; Richmond v. Deans, 281 U.S. 704

(1930 ); Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), and

that compulsory school attendance laws, if constitutionally

infirm, are not beyond their reach. Pierce v. Society of

Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925). See also Foster v. Com-

monwealth, Porter v. Commonwealth, (Records Nos.

2747, 2746, October, 1943, Term, Supreme Court of

Appeals o f Virginia, Unreported). Nor is the Common

wealth’s position in this connection assisted by the claim

that such laws are valid on their face (Commonwealth’s

Brief, pp. 6, 7 ). It is well settled that laws valid in gen

eral and ordinary operation may become invalid and un

constitutional as applied to particular situations. Dahnke-

Walker Milling Co. v. Bondurant, 257 U.S. 282, 289

(1921 ); Royall v. Virginia, 116 U.S. 572, 583 (1886 );

Poindexter v. Greenhow, 114 U.S. 270, 295 (1885) ; see

also Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (1951 ); Sny

[ 6 ]

der v. Massachusetts, 291 U.S. 97, 115-116 (1934 );

Quong Wing v. Kirkendall, 223 U.S. 59 (1912) ; Griffin

v. Norfolk County, 170 Va. 370, 376, 196 S.E. 698, 700

(1938) ; Carpel v. Richmond, 162 Va. 833, 843-844, 175

S.E. 316, 319 (1934).

Additionally, defendant further contends that the

compulsory attendance laws, properly construed with

reference to the facts and circumstances o f this case,

were not violated. The operative effect o f the segregation

laws is a factor relevant to determination o f this issue.

This was discussed in his opening brief (pp. 30-31), and

further elaboration is unnecessary.

Finally, if the unconstitutionality o f a statute may be

demonstrated by consideration of extrinsic evidence, it is

clear that the evidence offered by defendant at the trial is

competent, relevant and material to the issues presented

in this case. As the authorities discussed in the section

o f defendant’s opening brief devoted to this point (pp.

31-37) establish that unconstitutionality may be demon

strated in this fashion, the trial court erred in refusing

to receive and consider the same on the merits o f the

case.

II.

The Elements of Racial Segregation and Discrimination

Consequent Upon Attendance o f Defendant’s Child at

Hamilton-Holmes High School are Available in Defense

Against the Prosecution in this Case.

The Commonwealth claims that the elements of racial

segregation and discrimination consequent upon attend

ance of defendant’s child at Hamilton-Holmes High

[ 7 ]

School were matters as to which defendant’s exclusive

remedy was corrective civil proceedings and are not avail

able in defense against the prosecution in this case (Com

monwealth’s Brief, pp. 25-31). Examination o f this

position must commence with analysis o f Poulos v.

New Hampshire, 345 U.S. 395 (1953), upon which the

Commonwealth chiefly relies.

A. T he Poulos Case.

An ordinance of the City of Portsmouth, New

Hampshire, prohibited open air meetings on grounds

abutting public streets or ways unless a license therefor

should first be obtained from the City Council, and made

a violation of this requirement an offense punishable by

fine. Poulos and Derrickson, Jehovah’s Witnesses, applied

to the City Council for a license to conduct religious serv

ices in Goodwin Park, a public facility. They offered

payment o f all proper fees and charges and complied with

all procedural requirements. The license was refused.

They nevertheless held the planned services, and were

prosecuted for violation of the ordinance.

Significant differences between the instant case and

the Poulos case may be noted at the outset. Neither the

ordinance on which the prosecution was based, nor any

other law having operation in the factual situation

presented, made any distinction or classification on the

basis of religion or otherwise. From beginning to end

the defendants conceded, and the courts all held, that the

ordinance was valid in its general operation. There

appeared nothing that would render the ordinance invalid

in its application to Poulos or his companion; the arbi

trary refusal o f the license, while a correctable error,

[ 8 ]

would not affect the validity of the ordinance as to which

the error was committed. Consequently, the questions

in the case were different. A somewhat detailed analysis

o f the proceedings is essential to precise demonstration

o f the issues presented and the points decided.

The New Hampshire Proceedings:

Poulos and Derrickson were first tried, and wTere con

victed and fined, in the Portsmouth Municipal Court.

They took an appeal entitling them to a plenary trial in

the Superior Court. Before that trial, they moved to dis

miss the complaints on the ground that the ordinance

as applied was unconstitutional and void. Pursuant to

New Hampshire practice, this motion on the constitutional

question was transferred to the Supreme Court of New

Hampshire which sustained the validity of the ordinance

and discharged the case, State v. Derrickson, State v.

Poulos, 97 N. H. 91, 81 A. 2d 312 (1951), construing the

ordinance, and stating the issue and its holding, as follows

(97 N. H. at 93, 95, 81 A. 2d at 313, 315) :

“ The discretion thus vested in the authority

[city council] is limited in its exercise by the bounds

o f reason, in uniformity of method of treatment upon

the facts o f each application, free from improper or

inappropriate considerations and from unfair dis

crimination . . . The issue which this case presents

is whether the city of Portsmouth can prohibit re

ligious and church meetings in Goodwin Park on

Sundays under a licensing system which treats all

religious groups in the same manner . . . What we

do decide is that a city may take one o f its small

parks and devote it to public and nonreligious pur

poses under a system which is administered fairly

and without bias or discrimination.”

The result o f this action was to open the case for trial

in the Superior Court. That Court held that the ordinance

was valid, that the refusal of the licenses by the City

Council was arbitrary and unreasonable, but, in the

view that defendants should have raised the question of

their right to the license by appropriate civil proceedings,

refused to dismiss the prosecution on that ground.

The defendants appealed to the Supreme Court of

New Hampshire. Derrickson died before the appeal was

heard. That Court affirmed. Poulos v. State, 97 N. H.

352, 88 A. 2d 860 (1952). It considered that the prose

cution was “under a valid ordinance which requires a

license before open air public meetings may be held.”

(97 N. H. at 357, 88 A. 2d at 863.) It pointed out

that in State v. Stevens, 78 N. H. 268, 99 A. 723, L.R.A.

1917C, 528 (1916), the Court had established the rule

that a wrongful refusal to grant a license is not a bar

to a prosecution for acting without the license and that

“ This case clearly set forth the procedure to be followed

in New Hampshire by one who has wrongfully been denied

a license.” (97 N. H. at 355-356, 88 A. 2d at 861-862.)

Attention was called to the fact that “ in this jurisdiction if

a licensing statute is constitutional and applies to those

seeking a license, the remedy here provided consists of

proceedings against the licensing authority that has

wrongfully denied the license.” (97 N. H. at 356, 88 A.

2d at 862-863.) “ The remedy of the defendant Poulos

for any arbitrary and unreasonable conduct o f the

City Council was accordingly in certiorari or other ap

[ 1 0 ]

propriate civil proceedings.” (97 N. H. at 357, 88 A. 2d

at 863.)

Thus, the New Hampshire determination was that the

ordinance was valid on its face and that, accordingly,

Poulos’ remedy was by certiorari to review the unlawful

refusal o f the Council to grant the license, and not by

holding the services without a license and then defending

because the refusal of the license was arbitrary. That the

Supreme Court o f New Hampshire considered the issue

different where the law on which the prosecution is based

is invalid, either on its face or because of its application

in the particular case, is apparent from the fact that the

Court distinguished Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S.

296 (1940) and Hague v. Congress of Industrial Organi

sations, 307 U.S. 496 (1939) on the ground that they

involved prosecutions based on ordinances held to be un

constitutional, and Estep v. United States, 327 U.S. 114

(1946) and Gibson v. United States, 329 U.S. 338 (1946)

on the ground that the Selective Service orders there

violated were invalid. (97 N. H. at 356-357, 88 A. 2d

at 862-863.)

The Supreme Court Proceedings:

Poulos appealed to the Supreme Court of the United

States. The Court concluded that his contentions, which

the Court found “ difficult to epitomize,” (345 U.S. at

400), were as follows (Id. at 401-402) :

. . first, no license for conducting religious cere

monies in Goodwin Park may be required because

such a requirement would abridge the freedom of

speech and religion guaranteed by the Fourteenth

[ 1 1 ]

Amendment; second, even though a license may be

required, the arbitrary refusal o f such a licejnse by

the Council, resulting in delay, if appellant must, as

New Hampshire decided, pursue judicial remedies,

was unconstitutional, as an abridgement of free

speech and a prohibition of the free exercise of reli

gion. The abridgement would be because o f delay

through judicial proceedings to obtain the right of

speech and to carry out religious exercises. The due

process question raised by appellant as a part o f the

latter constitutional contention disappears by our

holding, as indicated later in this opinion, that the

challenged clause of the ordinance and New Hamp

shire’s requirement for following a judicial remedy

for the arbitrary refusal are valid . . . The state

ground for affirmance, i. e., the failure to take cer

tiorari from the action refusing a license, depends

upon the constitutionality of the ordinance.”

On the first contention, the majority of the Court,

accepting the New Hampshire construction, denominated

the license requirement “ a ministerial, police routine”

(Id. at 403) requiring “ uniform, nondiscriminatory and

consistent administration o f the granting of licenses for

public meetings on public streets or ways or such a park

as Goodwin Park, abutting thereon,” (Id. at 402) and

leaving the licensing officials “ no discretion as to granting

permits, no power to discriminate, no control over speech.”

(Id. at 404.) It considered that New Hampshire’s con

struction of the ordinance “ made it obligatory upon

Portsmouth to grant a license for these religious services

in Goodwin Park,” (Ibid), and assumed that “ with the

determination o f the Supreme Court of New Hampshire

[ 1 2 ]

that the present ordinance entitles Jehovah’s Witnesses

to hold religious services in Goodwin Park at reasonable

hours and times, the Portsmouth Council will promptly

and fairly administer their responsibility in issuing per

mits on request.” (Id. at 408.)

On the second issue, the majority concluded as follows

(Id. at 408-409) :

“ New Hampshire’s determination that the or

dinance is valid and that the Council could be com

pelled to issue the requested license on demand brings

us face to face with another constitutional problem.

May this man be convicted for holding a religious

meeting without a license when the permit required

by a valid enactment— the ordinance in this case—

has been wrongfully refused by the municipality?

“ Appellant’s contention is that since the Con

stitution guarantees the free exercise o f religion,

the Council’s unlawful refusal to issue the license

is a complete defense to this prosecution. His ar

gument asserts that if he can be punished for viola

tion o f the valid ordinance because he exercised his

right of free speech, after the wrongful refusal of the

license, the protection of the Constitution is illusory.

He objects that by the Council’s refusal of a license,

his right to preach may be postponed until a case,

possibly after years, reaches this Court for final

adjudication o f constitutional rights. Poulos takes

the position that he may risk speaking without a

license and defeat prosecution by showing the license

was arbitrarily withheld.

“ It must be admitted that judicial correction of

arbitrary refusal by administrators to perform offi

[ 1 3 ]

cial duties under valid laws is exulcerating and costly.

But to allow applicants to proceed without the re

quired permits to run businesses, erect structures,

purchase firearms, transport or store explosives or

inflammatory products, hold public meetings without

prior safety arrangements or take other unauthorized

action is apt to cause breaches of the peace or create

public dangers. The valid requirements of license are

for the good o f the applicants and the public. It would

be unreal to say that such official failures to act in

accordance with state law, redressable by state judi

cial procedures, are state acts violative o f the Federal

Constitution. Delay is unfortunate but the expense

and annoyance of litigation is a price citizens must

pay for life in an orderly society where the rights of

the First Amendment have a real and abiding mean

ing. Nor can we say that a state’s requirement that

redress must be sought through appropriate judicial

procedure violates due process.”

It is thus clear that the decision on the second issue

simply upheld New Hampshire’s procedural requirement

— o f correction by civil proceedings of a wrongful denial

o f a license— as applied to a criminal prosecution, under

a law valid both on its face and in its application, for con

duct without the license. The precise holding is epitomized

in the concluding sentences of the majority opinion {Id.

at 414) :

“ In the present prosecution there was a valid

ordinance, an unlawful refusal of a license, with

remedial state procedure for the correction of the

[ 1 4 ]

error. The state had authority to determine, in the

public interest, the reasonable method for correction

o f the error, that is, by certiorari. Our Constitution

does not require that we approve the violation of a

reasonable requirement for a license to speak in public

parks because an official error occurred in refusing a

proper application.”

But, more importantly, the majority and dissenting

opinions each emphatically pointed out that such a re

quirement could not obtain, nor could the defendant be

precluded from asserting the matter in his defense in

a criminal prosecution, if the law upon which the prose

cution is based is invalid either on its face or in its appli

cation. The majority opinion elaborately discussed Royali

v. Virginia, 116 U.S. 572 (1886), Cantwell v. Connecti

cut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940), and Thomas v. Collins, 323

U.S. 516 (1945), upon which Poulos relied in support

of his position, and stated (Id. at 413-414):

“ It is clear to us that neither of these decisions is

contrary to the determination of the Supreme Court

o f New Hampshire. In both of the above cases the

challenged statutes were held unconstitutional. In

the Royali case, the statute requiring payment of the

license fee in money was unconstitutional. In the

Cantwell case the statute had not been construed by

the state court ‘to impose a mere ministerial duty

on the secretary of the welfare council.’ The right to

solicit depended on his decision as to a ‘religious

cause.’ 310 U.S. at page 306, 60 S. Ct. at page 904,

84 L. Ed. 1213. Therefore we held that a statute

authorizing this previous restraint was unconstitu-

[ I S ]

tional even though an error might be corrected after

trial. In the Thomas case the section of the Texas

Act was held prohibitory o f labor speeches any

where on private or public property without registra

tion. This made Section 5 unconstitutional. The

statutes were as though they did not exist. There

fore there were no offenses in violation of a valid

law.”

Likewise, Mr. Justice Douglas and Mr. Justice Black,

dissenting, forcefully pointed out (Id. at 422) :

“ The Court concedes, as indeed it must under our

decisions, see Royall v. State o f Virginia, 116 U.S.

572, 6 S. Ct. 510, 29 L. Ed. 735; Thomas v. Collins,

323 U.S. 516, 65 S. Ct. 315; 89 L. Ed. 430, that if

denial o f the right to speak had been contained in a

statute, appellant would have been entitled to flout

the law, to exercise his constitutional right to free

speech, to make the address on July 2, 1950, and

when arrested and tried for violating the statute, to

defend on the grounds that the law was unconstitu

tional.”

Conclusions As To The Decision:

The Poulos decision does not sustain the Common

wealth’s position in the instant case. Rather, the differ

ences between the cases are quite obvious.

1. In the Poulos case, neither the ordinance on which

the prosecution was based, nor any other law having oper

ation in the factual situation presented, made any distinc

tion or classification on the basis of religion or other-

[ 1 6 ]

wise. The ordinance was valid on its face. There appeared

nothing that would render the ordinance invalid as ap

plied to Poulos; the arbitrary refusal of the license, while

an error for which the state provided corrective machin

ery, did not affect the validity o f the ordinance as to

which the error was committed. Thus, the case is simply

one in which “ there was a valid ordinance, an unlawful

refusal o f a license, with remedial state procedure for the

correction o f the error.” (345 U.S. at 414.) In these

circumstances, the requirement that Poulos resort to an

adequate civil remedy afforded by state law to correct the

error did not constitute a denial o f due process, and no

equal protection issue was involved.

On the other hand, the statutes upon which the present

prosecution was based are unconstitutional and void as

applied to the facts and circumstances of the instant

case. Since it is not the law that one must obey a void

statute, defendant is uninhibited as to making his defense

in this prosecution.

2. The issuance o f the license sought in the Poulos

case was a routine, ministerial function. As was found,

Poulos was plainly entitled to the license and the City

Council had no valid ground for refusing it. The proce

dure to correct the refusal, and the issue thereon, were

simple; lawyers would hardly consider the undertaking

magnitudinous. Mr. Justice Frankfurter, in his con

curring opinion, pointed out (345 U.S. at 419-420) :

“ There is nothing in the record to suggest that the

remedy to which the Supreme Court o f New Hamp

shire confined Poulos effectively frustrated his right

of utterance, let alone that it circumvented his con

stitutional right by a procedural pretense. Poulos’

[ 17]

application for a permit was denied on May 4, 1950,

and the meetings for which he sought the permit

were to be held on June 25 and July 2, In the absence

of any showing that Poulos did not have available a

prompt judicial remedy to secure from the Council

his right, judicially acknowledged and emphatically

confirmed on behalf o f the State at the bar o f this

Court, the requirement by New Hampshire that

Poulos invoke relief by way of mandamus or cer

tiorari and not take the law into his own hands did

not here infringe the limitations which the Due

Process Clause o f the Fourteenth Amendment places

upon New Hampshire.”

The Commonwealth points to the fact that the School

Board’s decision to relegate Negro secondary school

pupils to Hamilton-Holmes was known in July and argues

that defendant “ had a period as long or longer than

Poulos in which to seek relief. Section 22-57 of the

Code o f Virginia, 1950, provides for a quick and ex

peditious method of adjudication.” (Commonwealth’s

Brief, p. 28; see also p. 27.) The section referred to pro

vides as follows:

“ Any five interested heads of families, residents

o f the county, or city, who may feel themselves

aggrieved by the action of the county or city school

board, may, within thirty days after such action,

state their complaint, in writing, to the division

superintendent of schools who, if he cannot within

ten days after the receipt o f the complaint, satis

factorily adjust the same, shall, within five days

thereafter, at the request of any party in interest,

grant an appeal to the circuit court o f the county or

[ 1 8 ]

corporation court of the city or the judge thereof

in vacation who shall decide finally all questions at

issue, but the action of the school board on questions

o f discretion shall be final unless the board has ex

ceeded its authority or has acted corruptly.”

It is highly unlikely that this section provides a remedy

comparable to the New Hampshire remedies— certiorari

or mandamus— or of the character that the Supreme

Court had in mind. It may well be doubted that it affords

a judicial remedy; apparently the court simply exercises

administrative functions and issues an administrative

order on the appeal. The extent to which, if at all, issues

of the kind defendant raised in this case could be litigated

on such appeal is not clear. It is certain, however, that,

as the statute expressly provides that the court “ shall

decide finally all questions at issue,” its decision is final

and binding, and this Court has no jurisdiction to review

the proceedings, irrespective of the character of questions

presented. Jones v. County School Board of Brunswick

County, (Record No. 4090, October, 1952, Term, Un

reported). Significantly, any appeal by defendant under

the provisions of Section 22-57 would have gone to the

court in which the instant case was tried, and upon the

trial that Court stated that public school segregation is

valid (R . 100).

More importantly, the issue arising from the refusal

to grant Poulos a license, and the issues developing in

the instant case, are hardly in the same class. It is a matter

of common knowledge that substantially similar issues

have remained in litigation for years. Could the issues

presented in this case have been resolved in the short

space of two months in proceedings under Section 22-

119]

57, or for injunctive or other relief? To ask the question

is to answer it.

3. It was not incumbent upon defendant to seek cor

rection of unlawful conditions existing in the school

system. This was made clear in Sipuel v. Board of

Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948) where plaintiff, a Negro,

was refused admission to the only state-supported law

school in Oklahoma because o f her race. The courts of

that state denied mandamus compelling admission on the

ground that plaintiff should have requested the establish

ment o f a separate law school. The Supreme Court of

the United States reversed. When the case again came

before the Supreme Court, Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U.S.

147 (1948), the Court said (at 150) :

“The Oklahoma Supreme Court upheld the refusal

to admit petitioner on the ground that she had failed

to demand establishment of a separate school and

admission to it. On remand, the district court cor

rectly understood our decision to hold that the equal

protection clause permits no such defense.”

It is accordingly submitted that the holding in the

Poulos case has no application to the instant case.

B. Other Cases

The classic statement as to the effect o f an uncon

stitutional statute was made in Norton v. Shelby County,

118 U.S. 425, (1886 ):

“ An unconstitutional act is not a law; it confers

no rights; it imposes no duties; it affords no protec

[2 0 ]

tion; it creates no office; it is, in legal contemplation,

as inoperative as though it had never been passed.”

And that is precisely what this Court has stated its

effect to be. Campbell v. Bryant, 104 Va. 509, 516, 52

S.E. 638, 640 (1905).

This is the original and still the general doctrine. While

there have been some departures, see Chicot County Dis

trict v. Baxter State Bank, 308 U.S. 371 (1940), they

have not extended to conviction of a defendant upon a law

that is unconstitutional as applied to him. If the law

upon which the prosecution rests is unconstitutional, the

defendant cannot be guilty, and so must be acquitted.

See Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 (1946 ); Thomas

v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516 (1945 ); Cantwell v. Connecti

cut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940) ; DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S.

353 (1936 ); Royall v. Virginia, 116 U.S. 572 (1886 );

Miller v. Commonwealth, 88 Va. 618, 14 S.E. 161

(1892) ; Louthan v. Commonwealth, 79 Va. 196 (1884 );

Foster v. Commonwealth, Porter v. Commonwealth

(Records Nos. 2747, 2746, October, 1943, Term, Un

reported).

One would consider self-contradictory a contention

that the individual must conform to an unconstitutional

statute or must, if its enforcement invades his constitu

tional rights, seek redress in civil proceedings appro

priate for the purpose. Clearly he may elect to adopt the

latter course. But an unconstitutional statute cannot

impose an obligation to obey it and, without more, the

defendant prosecuted for violation of the statute may

assert the defense of invalidity in the criminal prosecu

tion. Thomas v. Collins, supra; Cantwell v. Connecti

[ 21 ]

cut, supra; Royall v. Virginia, supra. See also Morgan v.

Virginia, supra; DeJonge v. Oregon, supra; Miller v.

Commonwealth, supra; Louthan v. Commonwealth,

supra; Foster v. Commonwealth, Porter v. Common

wealth, supra. The rule is the same whether the uncon

stitutionality of the law appears on its face or arises from

its application in the particular situation. Royall v. Vir

ginia, supra. See also Foster v. Commonwealth, Porter v.

Commonwealth, supra.

In Royall v. Virginia, supra, there were statutes re

quiring- attorneys practicing in the state to obtain a

special “revenue license” and constituting practice with

out such a license a misdemeanor. When this legislation

was enacted, Virginia law permitted license fees to be

paid in either “ tax due coupons” o f the state or money.

Virginia subsequently enacted another statute requiring

license fees to be paid “ in lawful money o f the United

States.” Royall applied for a revenue license, tendering,

partly in “ tax due coupons” and partly in money, the

amount of the license fee. The license was refused.

Royall then engaged in practice without the license and

was prosecuted for doing so. The Supreme Court of the

United States held that the statute requiring payment

in money, as applied to this case, was unconstitutional

as impairing the obligations of a contract. (116 U.S. at

578-582.) The Commonwealth nevertheless pressed the

same contention made here, to which the Court gave

full and complete answers (116 U.S. at 582-583) :

“ Admitting this, it is still contended, on behalf o f

the commonwealth, that it was unlawful for the

plaintiff in error to practice his profession without a

license, and that his remedy was against the officers

[ 2 2 ]

to compel them to issue it. It is doubtless true, as a

general rule, that where the officer whose duty it is

to issue a license refuses to do so, and that duty is

merely ministerial, and the applicant has complied

with all the conditions that entitle him to it, the

remedy by mandamus would be appropriate to com

pel the officer to issue it. That rule would apply to

cases where the refusal o f the officer was willful and

contrary to the statute under which he was com

missioned to act. But here the case is different. The

action of the officer is based on the authority of an

act of the general assembly of the state, which, al

though it may be null and void, because unconstitu

tional, as against the applicant, gives the color of

official character to the conduct of the officer in his

refusal; and although, at the election of the aggrieved

party, the officer might be subjected to the com

pulsory process of mandamus to compel the perform

ance of an official duty, nevertheleess the applicant,

who has done everything on his part required by the

law, cannot be regarded as violating the law if,

without the formality of a license wrongfully with

held from him, he pursues the business of his calling,

which is not unlawful in itself, and which, under the

circumstances, he has a constitutional right to prose

cute. As to the plaintiff in error the act o f the gen

eral assembly o f the state of Virginia forbidding

payment of his license tax in its coupons, receivable

for that tax by a contract protected by the constitu

tion of the United States is unconstitutional and its

unconstitutionality infects and nullifies the antecedent

legislation o f the state, of which it becomes a part,

when applied, as in this case, to enforce an uncon

[ 23 ]

stitutional enactment against a party, not only with

out fault, but seeking merely to exercise a right

secured to him by the constitution. It is no answer

to the objection o f unconstitutionality, as was said

in Poindexter v. Greenhorn, ubi supra, [114 U.S.

270, 295, (1885)] ‘that the statute whose applica

tion in the particular case is sought to be restrained,

is not void on its face, but is complained of only

because its operation in the particular instance works

a violation of a constitutional right; for the cases

are numerous where the tax laws of a state, which in

their general and proper application are perfectly

valid, have been held to become void in particular

cases, either as unconstitutional regulations of com

merce, or as violations of contracts prohibited by

the constitution, or because in some other way they

operate to deprive the party complaining of a right

secured to him by the constitution of the United

States.’

“ In the present case the plaintiff in error has been

prevented from obtaining a license to practice his

profession, in violation of his rights under the con

stitution of the United States. To punish him for

practicing it without a license thus withheld is

equally a denial of his rights under the constitution of

the United States, and the law under the authority o f

which this is attempted must on that account and in

his case be regarded as null and void.”

The Royall case and the instant case are strikingly

similar in several respects:

(1 ) In the Royall case, like here, two different laws had

[ 2 4 ]

conjunctive operation. One was the law requiring the

revenue license and its companion section making it a

misdemeanor to practice without the license. The other

was the statute requiring payment of the license fee in

money, which conflicted with the Federal Constitution.

The prosecution, o f course, was under the misdemeanor

section, which was valid on its face. Nevertheless, it was

held that the prosecution could not be maintained. The

Court recognized that the laws there involved, like those

here involved, had an integral operation upon the de

fendant and the situation he occupied. Consequently, it

was held that the unconstitutionality of the statute re

quiring payment in money “ infects and nullifies the

antecedent legislation o f the state of which it becomes a

part, when applied, as in this case, to enforce an uncon

stitutional enactment against a party, not only without

fault, but merely seeking to exercise a right secured to

him by the constitution.”

(2 ) It was there contended, like in the Poulos case, that

Royall should have pursued his civil remedy against the

officers to compel the issuance o f the license, and that

Royall was nonetheless guilty because he practiced with

out the license. This claim was rejected. The Court

pointed out that mandamus would lie where the action

of the officer was wilful and contrary to the statute

under which he acted, but that in the case under considera

tion, like in the instant case, “ The action of the officer

is based upon the authority of an act o f the general

assembly of the state, which, although it may be null

and void, because unconstitutional, as against the appli

cant, gives the color of official character to the conduct

of the officer in his refusal.” So, while, as here, Royall

might, at his election, have initiated civil proceedings to

[ 2 5 ]

compel the issuance of the license, ‘ ‘nevertheless the appli

cant, who has done everything on .his. part required, by the

law, cannot be regarded as violating the law if, without

the formality of. a license wrongfully withheld from him,

he pursues the business of his calling, which is not

unlawful in itself and which, under the circumstances,

he has a constitutional right to prosecute.” Similarly, de

fendant may assert his defense in the instant prosecution.

(3 ) As stated before, the misdemeanor section, like

the compulsory attendance, laws here, involved, was valid

on its face, and invalidity developed through application

to the particular case. That made no difference. “ It is

no answer to the objection o f unconstitutionality .

‘that the statute whose application in the particular case

is sought to be restrained, is not void on its face, but is

complained of only because its' operation in the particular

instance works a violation of constitutional right.’ ” The

same conclusion necessarily follows: in the instant case.

(4 ) The Court significantly stated that Royall had

already been prevented from, obtaining a license to prac

tice his profession, in violation of his constitutional

rights, and that “ To punish him for practicing it without

a license thus withheld is equally a denial o f hisr rights

under the constitution o f the United States, and the law

under the authority of which this is attempted must on

that account and in his case be regarded as null and void.”

The same considerations obtain in the instant case.

Additional authorities might be considered. But. the

analogy of the Royall case is complete. It is strengthened

by the fact that in the Poulos case the Court took great

pains to distinguish it, and other cases like it, on the

ground that, unlike the Poulos case, the laws upon which

[ 2 6 ]

the prosecutions were based were unconstitutional either

on their face or in application.

The remaining cases cited by the Commonwealth are

inapposite. None involved a prosecution based on a void

law.

It is submitted that the Commonwealth’s contention

in this regard is without merit.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein and in his opening brief,

defendant respectfully submits that the judgment com

plained o f is erroneous and should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Oliver W . H ill,

Spottswood W . Robinson, III,

Martin A. Martin,

Counsel for Plaintiff in Error.

623 North Third Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia.