Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Joint Appendix Vol. III

Public Court Documents

March 26, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Joint Appendix Vol. III, 1990. da41bf45-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c8fc6fab-2ada-494a-ab46-ff1759120e1a/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-joint-appendix-vol-iii. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

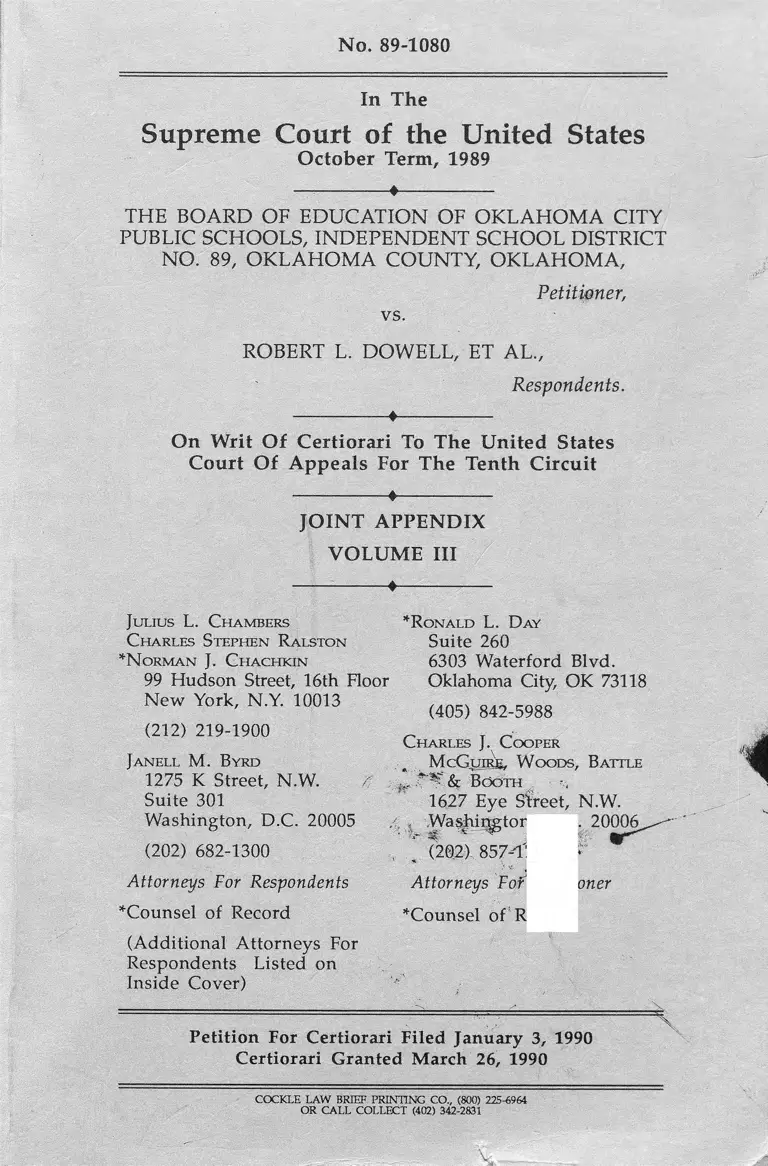

No. 89-1080

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1989

—------------♦--------------

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF OKLAHOMA CITY

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT

NO. 89, OKLAHOMA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA,

vs.

Petitioner,

ROBERT L. DOWELL, ET AL.,

Respondents.

--------------- «---------------

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States

Court Of Appeals For The Tenth Circuit

--------------- ♦---------------

JOINT APPENDIX

VOLUME III

--------------♦--------------

J u lius L. C h am bers *R onald L. D ay

C h arles S tephen R a lsto n Suite 260

*N o rm a n J. C h ach kin 6303 Waterford Blvd.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Hoor Oklahoma City, OK 73118

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

J a n ell M. B yrd

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys For Respondents

"̂ Counsel of Record

(Additional Attorneys For

Respondents Listed on

Inside Cover)

(405) 842-5988

C h arles J . C ooper

■ it*'

M cG uire, W o ods, B attle

& B ooth

N.W.

20006^

1627 Eye St

, Washington

* (202) 857-T7'

Attorneys For

^Counsel of Rec rd

tioner

Petition For Certiorari Filed January 3, 1990

Certiorari Granted March 26, 1990

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 22S-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

V

J o hn W. W a lker

J o hn W. W a lk er , P.A.

1723 So. Broadway

Little Rock, AR 72201

(501) 374-3758

L ew is B a r ber , J r .

B a r b e r / T r a v io lia

1523 N.W. 23rd Street

Oklahoma City, OK 73111

(405) 424-5201

Attorneys For Respondents

1

VOLUME I

Relevant Docket Entries............................... 1

Motion to Close Case............................................................ 29

Letter Opposing Motion (June 2, 1975)....................... .32

Opposition to Motion to Dismiss and Memo Brief

(June 30, 1975)............................. .34

Transcript of Proceedings at Hearing on Novem

ber 18, 1975 .................. ..................................................... 38

Order Terminating Case (January 18, 1977)............... 174

Opinion of the United States District Court For

the Western District of Oklahoma, 606 F. Supp.

1548 [1985]................. 177

VOLUME II

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals For

the Tenth Circuit, 795 F.2d 1516 [1986],............. 197

Final Pretrial Order (May 29, 1987) (Excluding

Witness and Exhibit Lists)............................................ 215

Excerpts from Transcript of Proceedings at Hearing

Conducted June 15-24, 1987

Record, Volume II

William A.V. Clark ............... ............. .......................235

Finis Welch........................ .............. ......................... 262

Record, Volume III

Finis Welch (continued).............................................. 274

Belinda Biscoe............................... 305

Susan Hermes ....................... 321

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Record, Volume IV

Susan Hermes (continued).........................................330

Clyde M use....................................................................334

John F in k ........................................................................344

Betty H il l ............................................. 347

Maridyth McBee................................. 354

Vern M oore.................................................................. 359

Betty Mason........................... 370

Record, Volume V

Betty Mason (continued).............................................375

Alonzo Owens, J r . ........................................... 379

Tommy B. W h ite ................................................... .. . 381

Carolyn Hughes............................................................389

Arthur W. Steller......................... 395

Karen Francis Leveridge............................................ 401

Odette M. Scobey.................................... 402

Linda J. Johnson........................... 410

VOLUME III

Record, Volume VI

Gary E. Bender.................................................. 418

Robert A. Brow n......................... 424

Billie L. Oldham......................... 428

John J. Lane.............................................. 430

Herbert J. Walberg. ............................. 436

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

Ill

Record, Volume VII

Robert L. Crain. .................... ............. .........................452

Yale Rabin. ................................................. . 463

Record, Volume VIII

John A. Finger, Jr................... ........................ .. 482

Mary Lee Taylor............... .......................................... 487

Gordon Foster.................... ....... ....................... .. 501

Record, Volume IX

Gordon Foster (continued) ....................................... 515

Clara Luper...................................................................516

Melvin Porter .......... ................ ...................... .......... 521

William Alfred Sampson.......................................... 524

Arthur S te ller............................................................ 531

Selected Exhibits Admitted Into Evidence at

Hearing Conducted June 15-24, 1987

Record, Supplemental Volume I

Plaintiff's Exhibit 48

Racial Composition of Elementary School Facul

ties, 1972-73, 1984-85, 1985-86, 1 9 8 6 -8 7 ............... 539

Plaintiff's Exhibit 50

1984- 85 Elementary Enrollment and Faculty -

Percent Black........................... ...................... 543

Plaintiff's Exhibit 52

1985- 86 Elementary Enrollment and Faculty -

Percent Black.................................................... ........... 546

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

IV

Plaintiff's Exhibit 54

1986-87 Elementary Enrollment and Faculty -

Percent Black.................................................... . 549

Plaintiff's Exhibit 56

Minutes, December 10, 1984, School Board Meet

ing....................... ....................... ..................... ............ . 552

Record, Supplemental Volume II

Defendant's Exhibit 5D

Population Change in East Inner-City Tracts,

1950-1980 .................................................... '................561

Defendant's Exhibit 5E

Black Population Turnover in East Inner-City

Tracts ................................. 562

Defendant's Exhibit 6

Population Growth/Change in Oklahoma City 563

Defendant's Exhibit 10

Abstract, Clark, Residential Segregation in Ameri

can Cities.................................................... 566

Defendant's Exhibit 11

Oklahoma City Public Schools, Percent Black in

Residential Zones ............................................... 568

Defendant's Exhibit 21

White Population in Oklahoma City SMSA,

1970-1980 ............. 571

Defendant's Exhibit 24

Black Population in Oklahoma City SMSA,

1970-1980 ................. 572

Defendant's Exhibit 38

School Districts in Comparably Sized SMSA's .. 573

Defendant's Exhibit 40

Indices for Residential Zones ................... .. 576

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

V

Defendant's Exhibit 45

Indices for All Schools.............................................578

Defendant's Exhibit 63

Racial Composition of Elementary Schools (K-4),

1985-86.......................................................................... 580

Defendant's Exhibit 67

Student Population by Race, 1970-1986........... 584

Defendant's Exhibit 76

Minutes, July 2, 1984 School Board Meeting.. .. 586

Defendant's Exhibit 79

Minutes, November 19, 1984 School Board Meet

ing....................... 602

Defendant's Exhibit 108

Majority-To-Minority Transfers.................................609

Defendant's Exhibit 119

Extracurricular Activities Report - High Schools 611

Defendant's Exhibit 120

Extracurricular Activities Report - Middle

Schools. .......................... 612

Defendant's Exhibit 140

Parental Organization Statistics............... 613

Defendant's Exhibit 142

Adopt-A-School Statistics............................. 614

Opinion of the United States District Court For

the Western District Of Oklahoma, 677 F. Supp.

1503 [1987] (Reproduced in Petition for Writ of

Certiorari at App. IB; not reproduced in Joint

Appendix)

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals For

the Tenth Circuit, 890 F.2d 1483 (1989) (Repro

duced in Petition For Writ of Certiorari at App.

1A [majority], 46A [dissent]; not reproduced in

Joint Appendix)

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

RECORD, VOLUME VI

418

GARY E. BENDER

* * *

[p. 831] Q. Do you serve on the Equity Committee?

A, Yes, I do. I'm chairman of the Equity Committee.

Q. How long have you been chairman?

A. Two years.

Q. Both years that it's been in operation?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Does the NAACP have representatives on the

Equity Committee, to your knowledge?

A. Yes, sir, to my knowledge, three.

Q. Does the Urban League have representatives on

the Equity Committee?

A. Yes, sir, to my knowledge, one.

Q. Would you explain for the court the type of

things that the Equity Committee has looked at during

these last two years?

A. What we've focused on is facilities and text

books, various areas of building maintenance, areas that

we felt that would be [p. 832] an equitable issue. Of

course, sometimes if - you run into if one bathroom leaks

and the other bathroom leaks across town, that's an equi

table issue.

But we have tried to make equity across the board so

that each child is being taught the same material, have

419

the same textbooks, the same material, the same oppor

tunity to learn.

Q. I'd like to direct your attention to defendant's

Exhibit 107, which is in evidence, and may be in the book

in front of you. That particular exhibit has already been

admitted into evidence as a document containing mate

rials concerning the activities and functioning of the

Equity Committee.

While you were on the Equity Committee, and in

doing this type of work did you make a determination as

to the condition of the facilities in the northeast quadrant

of the District as compared to other facilities throughout

the Oklahoma City District?

A. Yes, we did.

Q. What were your findings?

A. It was surprising. We found that the building

usage or the run-downness of the buildings were not in

the northeast quadrant, but they were also in the - there

were more in the south, southeast part of town. The

buildings in the northeast were fairly decent and compa

rable to the buildings in the north part of town.

Q. Did the Equity Committee do any studies

regarding the [p. 833] quality of teachers or the ability of

teachers or the degrees that teachers held throughout the

district?

A. Right. We asked for that. We came back and we

asked for that. We felt that there may be a loophole that

we were missing in equity if we didn't find out how the

teachers were fairly educationally in breakdown, and we

420

did do that study, and the study is contained in this

section here.

I would like to say that we did find out that teachers,

across the board, were teaching and children were learn

ing on a great - on a large scale, and they were profes

sionally involved across the district,

Q. Did the committee analyze the level of parental

involvement at the various elementary schools?

A. Yes, sir, and this is where we're going to have to

make the - a more bite in the equity issue, in that we

found that, even like in the Northeast Quadrant, if you

had a school who had an active PTA and PTO, then the

school was being supplied, the teachers were being sup

plied with everything they needed, whereas, right down

the street you had an inactive PTA, then there was an

inequity situation right there in the same neighborhood.

There's going to have to be more of a bite and an up

build of the PTA and PTO in the school district across the

board.

Q. Do you feel that as a result of the implementa

tion of the neighborhood plan that the level of parental

involvement in the [p. 834] district has increased?

MR. SHAW: Objection, Your Honor. Leading.

MR. DAY: I'm asking for an opinion.

THE COURT: Overruled.

Q. (BY MR. DAY) Let me restate my question.

A. Yes, sir.

421

Q. Do you have an opinion as to whether or not the

level of parental involvement in the Oklahoma City

schools has increased since the implementation of the K-4

neighborhood plan?

A. We have found that some PTA's have flourished

because of the neighborhood school program.

Q. Now, when the Equity Committee would find a

defficiency [sic] in any school in the district, what would

they do?

A. Well, a point in case, we found a very high

defficiency [sic] in Telstar, and we were very concerned

about the kids. They were disabled kids who were being

- didn't have the right facilities.

We immediately went back to the board - well, to

Elton Mathews and related our concerns to him, which

they - the district - I mean the board, the administration

got on it right away and corrected the errors.

And we found that throughout the two years, that

when we find defficiencies [sic], such as termite damage,

asbestos, or whatever, they were real helpful in respond

ing to that immediately and didn't let it lag, just got right

on it.

* * *

[p. 837] Q. What is your understanding of the

purpose of the majority-to-minority transfers?

A. Well, my understanding there is that the parents

have a right to have their child go anywhere they would

like them to go.

422

Q. For what purpose, though? What is your under

standing of the restriction?

A. To me it would be for convenience. At the time

Cory was going to Quail Creek, he could come back in

the first grade and go back to Village as a day care. We

didn't trust him with a key, but - and Candice was at

Quail Creek. And so - I'm sorry, Village.

Q. No, I didn't mean to interrupt you.

A. Oh, that's okay.

But - so we felt, as a convenience, they would be in

the same place, we are a close family, and to me it's just

convenience. Wasn't anything - that's why we opted that.

We have that option.

* * *

[p. 840] Q. I believe you mentioned that buildings

that have more active PTA's get more of something.

Would you describe what it is they get?

A. Well, it could be pencils. If you have an active

PTA and the teachers request - if you're familiar with

PTA, I'm sure you are - the parents - the teachers may

request something from the PTA, then the PTA would

respond to that need. If you didn't have an active PTA,

you could go in and find, in a case in point, pencil

sharpeners, each class would have one.

Q. Who is providing those pencil sharpeners?

A. The parents.

Q. The parents?

423

A. Right.

Q. And if the parents do not provide the pencil

sharpeners or the PTA is not active, then I take it that it

may be that the students will go without those pencil

sharpeners?

A. No, they'll just go with less.

* * *

[p. 842] Q. Part of the dissatisfaction has based

upon the notion that interaction occurred only once a

year, wasn't it?

A. Right. But in some schools it occurred three

yjtimes - in actuality in numbers, sometimes one school,

and that of King, had six occurences, three by letter and

^'three by visit.

So some flourished while others didn't, and that's -

that's our aim for this fall, to insure that that takes place.

Q. Why is the student interaction plan even neces

sary?

A. Well, it's a balance. It's - it's to help each child

that is in the - a child that's in another area know another

child and become familiar with that child so when they

get do [sic] a fifth-year school - center that they would

know each other.

Q. Why is that important?

A. Well, it's important for - as they grow, they learn

each other. They know the - when they get to another

school, they won't be so frightened, without having no

424

knowledge of individuals there. They'll know somebody,

have a friend there, they'll have acquaintances there.

* * *

ROBERT A. BROWN

[p. 848] A. * * * Incidentally, as a reading specialist I

was in the Chapter I Program.

I was an assistant principal at the Middle School level

for two years, and then last year moved to principal at

the elementary level.

Q. Where were you assigned immediately before

your assignment at King?

A. I was at Moon Middle School. That's in the same

area.

Q. Based on your educational background and

experience, do you have an opinion, Mr. Brown, as to

whether or not the racial composition of the schools

affects the academic achievement of black students?

A. It does not.

Q. And would you tell the court why you hold that

opinion?

A. I hold that opinion based on 17 years working

with predominantly black students. 18 years I'd have to

say now. And in that time what I have seen is that

blackness is just another element that you consider in

dealing with children. It does not predetermine or deter

mine what's going to happen to them educationally.

That's made up by the staff, by the teachers, by how you

work with the children.

* * *

425

[p. 849] Q. Was there any particular reason why you

wanted to be assigned to King Elementary?

A. I did not have a lot of - a lot of input as to where

I was assigned, but I was very pleased with the assign

ment. It matches well with my experience.

The students, academically, at King need the kind of

expertise that I have in the area of reading, and I think by

- you know, we were talking about that earlier just now. I

think that, by applying that expertise and by working

with that staff and by addressing those problems specifi

cally, that I'm in the right spot. I think I'll do some good

things for that school.

Q. Do you hold an opinion as to whether or not

parental involvement in the child's educational process

has an impact on academic achievement?

A. Certainly. It certainly does. Yes, it has an impact.

Q. Why?

A. The - the child that we deal with at school goes

home. If what we are doing is supported, is carried on,

even, at the home, then you've - you've got a better

chance to effect any kind of chance you want to. The

child's going to learn more.

I have a lot of parents that come in with concern

about children, and they will ask what they can do at

home, and they're given instructions and materials and

things that they can use at home. They can certainly make

an impact.

* * *

426

[p. 853] Q. At this point in time, Mr. Brown, do you

favor the school board's Neighborhood Plan?

A. Yes, I do.

Q. Why?

A. At my building, it's - it's generated a strong

sense of belonging, a strong sense of ownership among

the children. It's - it's developed a feeling about the

school that I didn't see, or at least didn't see as much of

in the days when they were transported all over the

district.

In my building I've got parents who are in the build

ing daily, and not just one or two, but several daily. I've

got PTA participation by parents who walk over who

would not be able to attend otherwise.

It enhances everything we do. The instructional pro

gram has improved. The teachers are able to make quick

contact. We have quite a few parents without telephones.

I've got teachers that go by their homes and see them

because they're right there [p. 854] in the area. I've got

parents that we can send letters home to and they show

up the next day.

To those of us that have been in the district a long

time, parents participation is definitely up.

Q. Have you personally noted an increase in the

level of parental involvement in the district since the

Neighborhood Plan was implemented?

A. In those buildings where I've been working, yes.

427

Q. Have you noticed any change in the discipline

problems of students since the implementation of the

Neighborhood Plan?

A. There's a - there's a quicker response from par

ents in discipline problems. I don't have near the prob

lems that we used to have in getting the parents to come

in. It's -

You know, as we go through the year there are some

kids that get in more trouble than other children, and I'm

getting those parents up without exception. I couldn't say

that in previous years. There were several people who I

never saw.

Q. Does King have a viable PTA unit?

A. Yes, it does. It's very active.

Q, Do - you mentioned earlier that those parents

sometimes come to school and volunteer to do various

things. Would you tell the court some specifics in that

regard?

A. Yes. Not only the PTA members, but we have

other parents as well, who will come into the building.

Because we're - because we're neighborhood and

they're [p. 855] able to just walk over in many cases, you

know, two or three blocks. They come in and they stand

in with classroom teachers. They work in a support room

there. They come in and support us on fund raisers.

Our major fund raiser was run almost completely by

parents this year, and, in this day and age of budgetary

considerations, that's real handy.

428

They tutor children. They help the teacher get mate

rial ready. It's not at all uncommon for the parents to be

running off things for teachers, to be going from different

- room to room to bring things to them. Just they're

involved in every way you can think of.

* * *

tp. 860] THE COURT: And what is that opin

ion?

MR. SHAW: Your Honor, I would just like to

note our continuing objection.

THE COURT: Yes, you have it.

THE WITNESS: I think that the Finger Plan

achieved the objective of creating a unitary district.

THE COURT: Do you have an opinion as to

whether or not the unitary system continued after the

court released its jurisdiction in 1977 to and through the

year 1985/6? Do you have an opinion?

THE WITNESS: Yes, sir.

THE COURT: And what's that opinion?

THE WITNESS: In my opinion, the unitary

school system is still going. It's still in existence.

* * *

BILLIE LEANNE OLDHAM

[p. 863] Q. Do you have an opinion as to whether or

not there has been an increase in the amount of parental

involvement in the school since the adoption of the

Neighborhood Plan?

A. Yes, I do.

429

Q. What is your opinion?

A. I feel like it's increased tremendously. I have

spent a lot of time in the different buildings across the

district helping them to organize their units, and I see a

great increase in our parental involvement.

Q. Do you believe that if the Neighborhood Plan is

allowed to continue that we will see additional increases

in parental involvement?

A. Yes, I do, because each year - when they first

start, it's usually just a handful of parents, but then as

they get going and the parents see that there is a real

value, you know, they want to continue to be involved. So

it will just continue to grow. Everybody wants to be

involved in something that's exciting.

Q. In your opinion, if parents become involved in a

PTA while their child are [sic] in grades K through four,

would they be more likely to remain active in the PTA

when their child attends grades five through twelve?

A. Yes, I feel like they would, because you're - just

like anything else, you are building a base.

* * *

[p. 868] Q. Do you - have you attended any national

PTA conventions?

A. Yes, I have.

Q. Do you have any knowledge about the trends in

PTA participation nationally over the past decade or two?

430

A. Well, not really. Not as far as - because I haven't

been involved in capacities that I could answer that ques

tion.

Q. Now, are you aware of the increasing participa

tion of women in the work force over the past decade?

A. Yes.

Q. And does that include, to your knowledge,

women who are the sole support of their families as a

result of divorce or other family changes?

A. Yes.

Q. For those parents who have returned to the work

force, would it be more difficult, in your opinion, for

them to participate in PTA activities than if they were not

in the work force?

A. It's more difficult maybe during the daytime, but

a lot of people have flexible job schedules.

That's part of the PTA's job. As our society changes

we, must make changes.

* * *

JOHN JOSEPH LANE

[p. 880] Q. And what inferences did you draw from

your conversations?

A. In terms of the individuals, I found them compe

tent, even enlightened, very well connected with national

organizations and what was going on beyond Oklahoma.

I would have to go so far as to say that, by any definition,

they are professional individuals.

I would have to say that, as I listened to them, I

gathered a picture of - beginning to form a picture of a

431

very progressive kind of district, fair in its public state

ment of policy. I found people very willing to be

involved.

I sensed that the board was very hard working and

willing, unlike what I have seen in other districts, frankly,

to be very collaborative with the central office.

Without waxing too eloquent here, or attempting to

be, I found, time and again, that their stated philosophy

of establishing excellence is, in fact, a dream, but it's one

that I think they're taking the steps to realize.

Q. Doctor -

A. They firmly believe that every child can learn.

Q. Doctor Lane, you have looked at a number of

other school districts. How does Oklahoma City School

District compare to those other districts?

[p. 881] A. In what regard?

Q. In implementing an effective schools program

and in carrying out their instructional philosophy.

A. It compares very favorably. As I look - as I

personally have tried to, over the years, develop effective

schools before it was in vogue to call them such, I have

found that this district, laboring under tremendous fiscal

constraints, has made giant strides.

In the area of communication with parents and

among the staff themselves, I - I've seen great progress.

In terms of leadership, emphasis on instruction, mon

itoring closely the progress of the children, it's really

already exemplary.

432

Q. Why did you then also conduct interviews?

A. Well, frankly, to get out into the field and see if

what I read and what I heard was true.

Q. And how did you go about conducting these

interviews?

A. I have already indicated that I had worked with

the North Central, and I opted to - to take that approach,

that I would - I had already read the documents, I have

visited with key individuals. I would now, instead of

visiting classrooms, I would visit individual school sites

and interview with the principals.

* * *

[p. 885] Q. So no principals felt like they were being

cut short or any favoritism shown; is that right?

A. That's correct.

Other kinds of questions in that regard dealt with

central office support for the schools, and here I was

looking for a kind of - I can't even say the word measure,

exactly - but a soft measure.

Over the years, I've also noticed that schools can be

excluded from connections, if I can put it that way, with

the central office. The principal calls and there's no

response. And I asked questions along those lines: "When

you call the central office, are you met with courtesy? Do

you feel that there is a response, that you will get sup

port?"

I was looking for two things, as I have said, one for

uniformity, but also, since the district says that it is an

effective school district, support for the local school is, in

433

addition to the five correlates of school effectiveness that

have been mentioned several times in testimony, school

support is yet another one, and I found, once again, that

all of the principals felt that when they called there was

response and support.

In the same vein -

Yes.

* Jfr Jfr

[p. 889] Q. Doctor Lane, did you also look at curric

ulum?

A. Yes, I did, with two particular things in mind.

One, of course, to see whether, in fact, the curriculum was

uniform across the board, and the other a more concrete

kind of thing. I've already referred to curriculum guides.

I wanted to know whether, in fact, curriculum guides

were available and were they being used.

I found that, in fact, the curriculum was uniform

across the board, that curriculum guides were being used,

but the principals, moreover, required lesson plans, and

these lesson plans involved the curriculum guides.

* * *

[p. 891] Q. Doctor Lane, there's been lots of discus

sion in the case about parental involvement.

In your professional opinion, how important is par

ental involvement to a student's education?

A. The two principal agents in the education of a

child are the teacher and the parent. Any program that

434

will bring the teacher and the parent closer together is a

good program, it seems to me.

The parent gains better understanding of the school's

objectives, the teacher's personal objectives, the teacher's

perception of his or her child, and they are able, collab-

oratively, to work for a better education for the child.

Furthermore, some experts have estimated that,

though it's quality time, we hope, a child is in school

about 13 percent of the time. 87 percent of the time,

between roughly birth and age 18, is spent out in the

community and with the family.

Anything that can augment the positive aspects of an

education in that neighborhood and with the parent and

the teacher is a positive thing and a good thing.

* * *

[p. 893] Q. So in every school there was some type

of involvement of parents?

A. Some type of - some type of involvement, with

the exception of two schools. I can't quite recall which,

but I do remember that there were two that didn't have

the them, but the other 28 schools did.

Q. Was it your impression that this involvement

had increased over the last two years?

A. It was the report of the principals that it had

increased, and, in some instances, had increased dramati

cally, some nothing that parent participation had moved

from 13 to 30, 35 members, which is - is quite an increase

over a period, frankly, of just a few months.

Q. Did you also look at facilities?

435

A. Yes, I - yes, I did. I didn't know until testimony

yesterday that there was need for about 200 million dol

lars in repairs, but, as a lay observer of that kind of thing,

I can - I can attest that there - the buildings of many of

them are in - in serious need of, perhaps, some structural

changes and improvements.

Nonetheless, I found that the schools were clean, well

maintained, and, in accordance with both my inquiry

about uniformity and about matters relating to school

effectiveness, they provided safe environments.

[p. 894] Some principals did express concern about

the presence of asbestos, and I understand that that's

before the board and they understand that something

needs to be done.

Q. But was it your general impression that there

was uniformity among the schools regarding their facili

ties?

A. As with finance, as with teachers, as with facili

ties, the principals reported that, in fact, the district is

financially strapped, if one suffers, we would all suffer.

That, in fact, the formulas devised for allocation of

resources were very scrupulously followed.

* * *

[p. 897] Q. In your professional opinion, and based

on your observations throughout the district, is the effec

tive schools program working here in Oklahoma City?

A. Yes, indeed it is. In addition to the five correlates

that they have announced as characteristics of school

effectiveness, more recent research has lengthened the list

a bit to include the very kinds of things the district is

436

doing; namely, other hallmarks of an effective school are

those which, in addition to the five that have been men

tioned, strong instructional leadership through monitor

ing, include also such areas as involvement of parents,

collaboration between the central office and the site-level

schools, support from the district office up and down the

line, planning and communication, and these are in evi

dence.

Q. Does the Neighborhood School Plan enhance an

effective schools program, in your opinion?

A. Yes, it does, because a neighborhood school can

insure greater parental involvement, and one of the hall

marks of an effective school is parental involvement.

Neighborhood schools perhaps can help in that - in that

regard.

Proximity means easy access, and that's very good,

and the neighborhood school does help that.

Q. In your professional opinion, is a Neighborhood

School Plan educationally beneficial?

A. Yes, it is.

* * *

HERBERT JOHN WALBERG

tp. 913] Q. Doctor Walberg, do you have an opinion

as to whether or not the racial composition of a school

has an effect on academic achievement?

A. Yes, I do. I think that racial composition of the

school is irrelevant to how much children learn in school,

and no particular racial composition, such as zero, ten,

fifty, ninety, or a hundred makes important difference for

how much children learn in school.

437

Q. What do you base this opinion upon?

[p. 914] A. May I consult my notes, Mr. Day?

Q. Certainly.

A. I base this opinion on a series of studies that

have been done since 1966, the first of which was the -

sometimes called the Coleman report. It was the survey

of "equality of education opportunity," which was a

study of some 600,000 elementary and secondary stu

dents throughout the United States, carried out for the

United States Congress.

There have been analyses of that survey, and they

have indicated, collectively, no relationship of - that is,

black-for-black learning, how much black students learn

in school to the racial composition of a school, or at least

inconclusive results and a great deal of disagreement.

There have also been major compilations of smaller-

scale studies, particularly various kinds of programs to

change, either on a voluntary or a mandatory basis, the

racial composition in cities and in metropolitan areas.

Some of the reviewers of this have included Nancy Saint

John Others.

I would say that perhaps the most important com

pilation of this evidence was conducted by the National

Institute of Education in 198— 1982, in which six investi

gators who had experience in doing research on this

particular question were brought together by the United

States Department of Education to try to resolve this

question. The results of the compilation indicated an

inconsistent and a very small effect, very [p. 915] close to

zero, such that some studies had had a positive - a small

438

positive effect, some studies have had a negative effect,

but in comparison with the kinds of things that I had

talked to you about earlier, these nine factors, they were

extremely inconsistent and had little impact on learning.

Followups on that, such as Dennis Cutty in 1983, who

reviewed this whole compilation, and I'd like to quote

what he said.

"The conclusion to be drawn from these 19 best

studies is that desegregation has not significantly

improved black achievement levels. What slight positive

nonsignificant gains there were in the 19 studies, came

from the 14 voluntary programs as the five mandatory

programs^sj&wed collectively either no gain or an actual

decline in academic achievement."

Now, this is the basis for my conclusions.

Q. In your opinion, will the fact that some students

in Oklahoma City next year will be attending K-4 elemen

tary schools that are not precisely racially balanced have

any effect on the academic achievement of those students,

either black or white?

A. I don't think it will have any effect at all.

Q. Doctor Walberg, do you have any opinions con

cerning the academic benefits which neighborhood

schools offer?

A. Yes, I do.

Q. Would you tell us about those?

[p. 916] A. I mentioned the studies of parental

involvement or what I call the curriculum of the home,

439

and in compiling studies, I have published a review of

this literature of the studies that had been made through

out the United States in the last 20 years and found that

these studies had extremely good consequences for the

academic learning of children.

Most of the studies - the experimental - that is to say,

the randomized field trials in which some children were

given special parental involvement programs, or the cur

riculum of the home, special tutoring and close relation

ships between the parents and students, indicated quite

sizeable and consistent results.

In addition to that, I personally conducted a study in

Chicago about a dozen years ago in an all-black area of

the city of highly educationally disadvantaged students. I

was asked to help plan the particular program and also to

analyze the statistical test scores, and I also found in my

own personal studies that there were quite strong and

good effects.

* * *

[p. 918] Q. Have you reached any conclusions as to

the educational offerings presently in the Oklahoma City

School District?

A. Yes, I have. In my opinion, the school board

goals and their plans are great aspirations. They have

decided to have an urban thrust to strive to become a

nationally-recognized model urban district.

They have a number of other goals which they've set

forth for themselves, and most important of those is the

general excellence in student achievement and learning.

440

They've tried to, among other goals, assure equity,

pride, and success in the reassignment plan, create a

positive teaching-learning environment, upgrade the

instructional effectiveness of teachers and the instruc

tional leadership of administrator. They have attempted

to target financial resources to effectively achieve short

term and long - priorities and short range plans.

And finally, they have tried to build harmonious

working relationships among the board, superintendent,

employees, residents, and other interested parties.

[p. 919] I would say that they have set forth these

goals and concentrated their efforts on that.

In addition, that's already been mentioned, they have

mounted what I consider to be an extremely ambitious

and successful school effectiveness program with the five

major goals that have already been described. But, in

addition to that, I consider the parental involvement pro

grams highly - have been increasing vastly, and they've

also been very successful.

I would say, finally, that the school district has been

extremely successful in trying to base what they do on

educational research. They have a good - excellent, I

would say - research facility. They've been collecting an

immense amount of achievement date and putting a

strong focus on trying to choose those kinds of programs

that would help most effective in helping all the children

with respect to their learning in the Oklahoma City Public

Schools.

Q. Where do you see the school district headed?

441

A. I think that the school district, if it keeps these

programs in place, and also can increase the - make them

more - still even more widespread, - and I think that they

are near the national norms now. I think they've been

increasing in the last couple of years, but I think that they

can increase still further.

In particular, I think that it's cause for celebration, [p.

920] having more PTA's and PTO's and increasing the

membership, but I think that the school district can push

things even further to get not only some parents in the

school but more parents in the school.

And secondly, I think that we have the beginnings,

although it's very valuable to raise funds, and I think that

the school district is strapped for funds, but I think - and

the parents have been able to raise additional funds for

the school, but I would like to see them doing even more

than this in having what I would call more of this curricu

lum of the home or parental involvement, such that some

of the activities could be focused on more volunteering of

parents in the schools, more tutoring - voluntary tutoring

in the schools, and having the teachers giving hints for

the parents and various kinds of program activities that

they can carry out at home, particularly involving home

work and other kinds of activities that research has

shown has been very conducive to learning and educa

tional achievement.

Q. So I take it, Doctor Walberg, you are of the

opinion that parental involvement does have an impact

on student academic achievement?

442

A. It has an extremely consistent impact, and it also

has a very large impact from the studies that have been

made throughout the United States in the last 20 years.

Q. What conclusions did you reach based on your

interviews [p. 921] with the PTA presidents?

A. The conclusions that I reached is that the major

activities that they have been engaging in is raising

money for the schools. They've also had a series of volun

teer activities, such as book fairs of various kinds.

The other activities include some tutoring and some

provisioning of information about what the school dis

trict is trying to do and the unique characteristics of that

particular school, as well as providing information about

the personal requirements that teachers may have or

what the teachers are trying to do with particular chil

dren.

I also sensed from my interviews with the PTA presi

dents and other representatives that they believe strongly

in the value of parental involvement; that is to say that

many of them believe that it - and mentioned that it

promotes learning; that it promotes a pride in the school,

that it increases friendships of children and parents and

parents with one another; that it is exceptionally good for

discipline, because the parents can be very - in close

touch with the teachers.

They also mentioned that parents can support one

another's efforts by knowing what other parents are

doing in the school.

443

They also mentioned the fact that parental involve

ment can promote more homework, which is very condu

cive for additional learning.

Other conclusions that I made is that a number of the

[p. 922] parents wanted to increase the membership in

their school and also increase the scope of activities,

particularly along the lines that I was suggesting earlier,

not just raising funds, but more volunteers in the school

and more parental involvement.

I also thought that it was interesting that in some

cases grandparents were involved with the PTA. And so

there was some sense of inter-generational continuity

from one group to the other.

There were a number of other miscellaneous points

that people mentioned about how they might send some

of the children to camps, for example.

And then I also looked into the question and asked

them about the - whether they believe that, for those that

were in the K-4 schools, whether distance was a factor in

parental involvement, and I learned that they felt that it -

when the parent is closer to the school, it minimizes the

distance - some of them view it as a safety factor. Some of

them also mentioned the fact that it was much more

practical, and that they could increase their - that par

ents, generally speaking, could be more involved in the

school if they live closer by and it was easier for them to

get there.

Those were my main conclusions.

* * *

444

[p. 927] Q. Do you draw any particular significance

from this exhibit, doctor?

A. Yes. I have - I can look at this exhibit and see

that, although there are some exceptions, generally

speaking the higher the percentage of students that have

free lunch in the school, the lower the achievement levels,

and the fewer the children that get free lunches, indicat

ing higher socioeconomic status school, the higher the

achievement levels within the school.

Q. Which elementary school in the district had the

lowest achievement scores, overall?

A. I believe that the Willard School, which is second

- numbered second, has the lowest achievement.

Q. And what is the achievement NCE for Willard?

A. It's 37.7.

Q. Now, what percent of the students attending

Willard were receiving free lunch?

A. 81.1 percent.

Q. And what percent of the student body at Willard

is black?

A. 6.6 percent.

Q. What percent is other minority?

A. That's 51.9 percent.

Q. And what is the percent white?

A. 41.5 percent.

[p. 928] Q. Now, do I understand correctly doctor,

that the Willard School, which was only 6.6 percent black,

445

had, overall, scored lower on achievement tests than any

of the schools in the district that are 90 percent or more

black?

A. That's correct.

Q. I'd like to direct your attention at this time to

Exhibit 184, which has also been received in evidence,

and I'd like for you to identify an[d] explain that exhibit

to the court.

A. Defendant's Exhibit 184 is entitled "Oklahoma

City Public School's Third Grade Metropolitan Achieve-

ment Test."

It shows, for two school years, the students' national

percentile rank on read - the reading and the mathema

tics test on the Metropolitan Achievement Test. The two

school years are 1985/86 and also 1986/1987.

Q. What significance do you find in this exhibit?

A. I find that when the total population of the

school district is examined at the third-grade level where

test scores were available, that there has been improve

ment in achievement from 1985/86 to 1986/1987.

In the subject of reading, the percentile went from the

43rd to the 45th, and in the subject of mathematics, the

school district went from the 45th percentile to the 51st

percentile, which is above the national average.

* * *

[p. 933] Q. (BY MR. DAY) Just briefly identify the

exhibit for the court and explain it, please, sir.

446

A. This is entitled "Oklahoma City Public Schools

third grade achievement results by race." It shows the

mean normal curve equivalent score on the metropolitan

achievement test for the two most recent school years,

1980 -

I'm sorry, I have the wrong exhibit here.

It's third to fourth grade gains. I'm sorry. This is for

the schools that are - have more than 90 percent black

students in them. Gives the names of the schools across,

going from Creston Hills and including Dewev, Edwards,

Garden Oaks, King, Longfellow, North Highland, Parker,

Polk, and Truman.

It shows that the students in these black schools,

predominantly black schools, are making substantial -

have played substantial gains during this - from third to

fourth grade in the period 1986 to 1987. Eight of the ten

are positive. One or two schools did not make such high

gains, but [p. 934] they lost only slightly.

And, on average, if you look across all of them, you

can find that there is a substantial gain since the institu

tion of the K-4 Plan.

Q. Do you have an opinion as to what's responsible

for the recent gains of black students?

A. I believe that the programs that I have described

and have been described here in testimony in the last day

or two are the reasons why students in these schools are

gaining more than perhaps they have in the past.

Q. Do you believe that the neighborhood school

program for grades K through four, in and of itself, in any

way contributed to the gains made by black students?

447

A. I believe that it is one of the contributing factors.

Yes.

Q. And do you also believe that the level of paren

tal involvement may affect these scores?

A. Yes, I do.

Q. Doctor Walberg, did you direct the preparation

of all of the graphs in Exhibit 185?

A. Yes, I did.

Q. Did you check the accuracy of the numbers?

A. Yes, I did.

* * *

[p. 942] Q. So the figures shown in the representa

tion - the bar graph representation for King and Garden

Oaks are losses. They're not lesser gains. They're losses.

A. Well, perhaps I should clarify this. This is gains

and losses, or, I should say, changes in general relative to

normal progress in school.

So I could say that all the students were making

gains in some sense, because they learned something

during the course of the year. But eight of the schools

made gains that were larger than those of the national

average and two schools made gains that were less than

the average gains made in the United States.

* * X-

[p. 944] Q. You are aware, aren't you, that in grades

five through twelve the district carries out a mandatory

busing program to maintain desegregation and racial bal

ance?

448

A. Yes, I'm aware of that.

Q. So it's fair to say that an effective schools pro

gram can be carried out in a desegregated setting, and

even in the context of a mandatory plan?

A. That's correct.

Q. And is it also true that the factors you identified

as most strongly associated with learning, to the extent

that they are under the control of or can be affected by

school system action can be provided or enhanced in

desegregated schools or in a system carrying out a deseg

regation plan?

A. Well, I need to say that it's possible to do these

things at the same time, but I also need to remind myself,

or to give a full answer, that if there are expenditures

involved, such as monetary expenditures for effective

schools or for transportation, or if the district has a finite

amount of energy and attention that they can give to

things, if they are doing two things simultaneously one

can take away from the other.

So, while it's theoretically possible to do two, three,

or four things simultaneously, we do have to consider the

amount of resources that are expended on each activity as

well as the benefits involved.

Q. Well, you're not saying, are you, that if you were

con- [p. 945] suited by a school district that was carrying

out a mandatory desegregation plan and wished to

implement an effective schools program that you would

suggest to them that they should dismantle their deseg

regation plan in order to implement an effective schools

program?

449

A. No, I would not do that. I think they have to

simply assess the amount of energy, resources, financial

resources that they have and come up with the thing

that's in the best interest of the children.

Q. Now, you said you thought there would be no

effect on achievement from attendance at any of the more

than 90 percent black schools next year. Is that -

A. Yes, I think that was concerned with the question

whether the racial percentage would have an effect one

way or the other.

Q. And did you mean to suggest in that answer a

comparison with attendance at a, perhaps, majority white

school?

A. Yes. I think I was being asked to illustrate the

point that racial composition of the school, in my opinion,

does not have a consistent effect on how much black

students learn.

Q. But isn't it correct to say it would be difficult to

determine the impact of moving from a school of - a more

racially mixed school to one of these 90 percent black

schools, for example, between the last year of the Finger

Plan and the first year of the new student assignment

plan, by looking at [p. 946] the test scores that have been

made since then, because there were other changes in

programs, such as the implementation of the effective

schools program at the same time? I mean, we're never

really going to be able to know for sure what was really

happening, since the two changes occurred almost simul

taneously in the district.

450

A. The two changes you are referring to are the

reversion to the neighborhood schools at grades one

through four and the effective schools program?

Q. Correct.

A. And I think I would mention, as well, the

increased parental involvement at that point in time.

Q. Well, -

A. I think it's - I think it's difficult to give the exact

weight, but I do think that there's been considerable

research on effective schools in terms of involvement that

suggests that those things would be conducive to

achievement, so that if achievement had, in fact, gone

down, then I think that that would be quite surprising.

Q. But the fact that achievement has gone up would

not be conclusive. I mean, it would be theoretically possi

ble, for example, that for students assigned back to

heavily black schools, if there was a negative effect on

achievement of some dimensions, it might be outweighed

by the positive effect of some parental involvement and

effective schools program, the [p. 947] factors that you've

mentioned.

A. Well, in my own opinion, I think that the paren

tal involvement and effective schools would lead to

higher achievement, and I say that on the basis of my

school visits and the interviews and the other studies I

have made also, since there have been so many studies of

this throughout the United States.

So I don't think we can be absolutely certain of

anything in educational research, but I think that there's -

I would have very strong confidence that the parental

451

involvement and the effective schools would be the two

major causes of improvement.

* * *

[p. 953] THE COURT: Did you find any dis

crimination between whites and blacks in your study of

the school system?

THE WITNESS: I did not.

THE COURT: Did you make a further study of

whether or not this court should continue supervision of

the school district?

THE WITNESS: I had only thought of that

question since you raised it the last day or two, Your

Honor, -

MR. CHACHKIN: Excuse me, Your Honor.

Respectfully, again I object to the somewhat different

question than the court has previously asked. I believe

and I think it's very clear that that is a decision for the

court to make to a legal issue in the case, and I don't

think this witness is qualified to make it.

THE COURT: Well, I disagree with you on that.

And I think I should at this point - I haven't done it

before, but it's been in the back of my mind.

The pretrial order, agreed to between the parties,

paragraph 7 of the contentions of the defendant reads

* * *

RECORD, VOLUME VII

452

ROBERT L. CRAIN

[p. 971] Q. Have you reached any conclusion?

A. Yes. I think segregated schools are harmful from

American standards, are harmful to black students

because they would inhibit their learning as reflected in

the standard achievement test scores, and it would inhibit

their ability to finish high school and to finish college. It

reduces, somewhat, their political participation. Gradu

ates of segregated schools have worse employment pros

pects.

You could also - the evidence would also be that

white graduates of segregated schools are somewhat -

have somewhat more difficulty in interaction, friend

ships, and conversation with blacks, and are somewhat

more prejudiced.

I'd say those are the main factors that one should talk

about.

Q. What is the basis for your conclusion that segre

gated schools have harmful academic effects and desegre

gated schools presumably do not?

A. Mainly, the META analysis that I did for - origi

nally for the Ford Foundation and the later one I did for

the National Institute of Education. The later one sur

veyed 93 different studies of desegregation achievement.

Most of these were - many of these were doctoral disser

tations written by school principals and school adminis

trators around the country about their own school

districts, and I analyzed these studies and found a pat

tern indicating that black students from segregated [p.

453

972] schools tended to score less well on standard

achievement tests.

Q. Were the results of your analysis uniform?

A. No. there's a - there's been a clear discrepancy,

because about half of the studies done show a sort of

clear positive effect of desegregation, and the other half

show essentially no effect at all. Occasionally a study will

actually show there are negative effects of desegregation.

Q. You're talking about effects on what students?

A. On black students. On black student achieve

ment test scores.

Q. Did you study the effects on white students' test

scores?

A. No, I didn't. That question was studied several

years ago by several different people. They always found

that white test scores were not affected by desegregation,

and I think, as far as I know, all sociologists and psychol

ogists think of that as essentially a closed issue. No-one

has studied it for the last ten years.

Q. So you were studying then the effects of aca

demic achievement on - of desegregation on black stu

dents only, -

A. That's right.

Q. - and the results were not uniform?

A. That's right.

* * *

[p. 1003] Q. Doctor, -

454

A. Can you do this whole analysis a different way.

what I've done here is to look at the same cohort as they

move from one grade to another, but that means you're

switching from one test to another.

A simpler method would be simply to look at the

same grade and say, "This is a reasonably large school

district. You wouldn't really expect the students who

entered - who were, say, thirteen years old to be terribly

different from the students that are twelve years or the

students who are fourteen years old at any one time. Let's

simply look at all the students who were first graders in

1984, all the students who were first graders in 1985, and

students who were first graders in 1986.

Q. I was going to ask you about that, Doctor Crain.

You have been talking about tracing cohorts through.

A. That's right.

Q. Now you're talking about comparing the first

grade in one year with the first grade in another year, and

then doing the same thing for other years.

A. That's right.

Q. For the grades rather?

[p. 1004] A. Yes, we're comparing grades. We're

comparing different cohorts to each other.

If you do that, you get almost exactly the same pat

tern. For example, the first grade gap in the fall of '84 was

eleven points, in the fall of '85 was eleven - the spring of

'84 was eleven points, spring of '85 was eleven points,

spring of '86 was fifteen points. The gap had gotten

worse.

455

That's also true for the second grade, that's also true

for the third grade. There's no difference in the fourth

grade. It's also true for the fifth grade.

On the other hand, in the upper grades, six through

eleventh, the gap got worse in 1986 in only two cases and

got better in four cases. So, you see the same pattern

again in the upper grades. There is improvement in the

gap, declining. In lower grades the gap - the lower

grades, the gap has gotten worse.

Now, this is not very strong evidence that Oklahoma

City is following the national trend in which segregation

is more harmful to achievement. I would expect that to be

the case, but this is really not very strong evidence,

because it's the first year of the plan, and students were

moved around, teachers were moved around, and you

would expect some amount of disruption.

// The best I can say is that certainly the new effective

\ schools program that I've read some literature about is

(working [p. 1005] in the upper grades better than it is the

/ lower grades, and there's no evidence here that - that - at

/ least I would not interpret this as giving any evidence at

/ all to indicate that students are doing better because

they're in a neighborhood school. You would have to say

the students are doing worse. Maybe they'll do better in

some future year, but they're not doing better not.

They're doing worse.

Q. Doctor, you've indicated that the time which has

passed between the implementation of the plan and now

makes it difficult to do a definitive analysis and reach

definitive conclusions.

456

A. Uh-huh.

Q. Would that be - is that your experience in other

situations?

A. Yes. I have worked with achievement tests in a

number of studies, and I've studied desegregation plans.

You do want some time for things to settle down, and

especially you don't want to compare two different tests.

It's always very difficult. Well, you just don't want to do

it. You can't do it most of the time.

* * *

[p. 1008] A. * * * If that's the case, then I would

summarize these results as follows: They indicate that

black families who live in racially mixed and predomi

nantly white neighborhoods have children who score

higher on tests than black families who live in the ghetto,

and I would be absolutely astonished if that were not the

case, and it has absolutely nothing to do with riding a

bus.

This research is absolutely indefensible. No social

scientist in the country would accept this as competent

research. You have to control, you have to match students

on their background characteristics and on previous abil

ity, and every study that possibly could be published

does that. You just have to do that, and this doesn't do it.

* * *

[p. 1011] Q. In your view, does this provision offset

the damages that you have described?

A. No.

Q. Why not?

457

A. They simply - they simply operate at - it's a way

of operating a segregated school system by inviting the

black families to participate in the process of creating

segregation so that it can have a sense of democracy

about it. But it's not -

Q. What do you mean by that?

A. I mean, in a society where blacks have grown up

treated unequally and been separated from whites, it

would be astonishing to expect very many blacks to

volunteer for the frightening experience of sending their

child across town to an all-white school. It's - it's a

burden, it's a lost less efficient that having bus that shows

up to take all the kids, you have to separate your child

from all his friends, and you have to run this risk of

dealing with these whites on the other side of town. You

can't expect black families to be willing to risk that.

Consequently, I think anyone who draws a plan

which puts this provision in knows that only a tiny

percentage will take advantage of it, and that most stu

dents will remain in segregated schools.

* * *

[p. 1019] Q. Doctor Crain, one more area of inquiry.

Do you advocate the same - Do you reach the same

conclusions with respect to desegregation when it comes

to choices regarding higher education?

A. No.

Q. Why not?

A. I think black colleges - I think it's a big mistake

on the part of the Federal Government to - to press for

458

the total desegregation of black colleges, and 1 think the

Federal Government learned that lesson and, in fact, has

backed away from that position.

In a situation where college attendance is voluntary,

there are some black students who would be very uncom

fortable in a desegregated or predominantly white college

and for whom a black college would provide a good

educational opportunity for them.

* * *

[p. 1028] Q. My question to you is this: In your

opinion, - I'm not concerned about someone else's opin

ion - is an urban community like Oklahoma City, through

the implementation of a court-ordered desegregation

plan, capable of eliminating residential segregation by

itself?

A. Well, the school district wouldn't do it without

the help of the City Planning Department, the zoning

board, and all the - I mean, if the rest of the city wants

the school system - if the rest of the city wants residential

segregation, the school system is going to be swimming

upstream. But if you put together a concerted effort over

the next 50 years of -

I've written -

Q. Well, I think you -

A. - on exactly the things the school district could

do to create residential integration, -

Q. I think you've answered my question.

A. Oh.

459

[p. 1029] Q. You've told me that, standing alone, a

school district such as Oklahoma City cannot do that.

A. Okay.

Q. There must be significant effort from all other

governmental entities in the community; correct?

A. That's right.

Q. And, in fact, do you know of any court-ordered

desegregation plan in an urban community similar to

Oklahoma City which has successfully eliminated resi

dential segregation in that community?

A. I don't know any school district which has elimi

nated all residential segregation, however, I have been

quite surprised in this research that I've done with

Dianna Pierce and others about the impact in the change.

* * *

[p. 1066] Q. * * * would you agree that parental

involvement in the schools has a significant impact on

black academic achievement?

A. Yes.

Q. You mentioned the effective schools program,

and I think [p. 1067] you indicated you didn't think that

we have had time in Oklahoma City to see the results of

that; is that correct?

A. Well, I don't know whether you have or not.

Q. Well, what did you testify on direct? Have you

analyzed Oklahoma City's effective schools program?

A. No.

460

Q. So you don't now what impact it's having on

academic achievement, do you?

A. No.

Q. Are you aware that this school district has a

bilingual program?

A. I would - I would assume - I assumed it had

one.

Q. Don't you think that can have a positive effect on

achievement?

A. Yes.

Q. Now, we've been talking about achievement.

Let's switch gears now and talk about the success of black

students in adult life.

Would you agree with me that, besides racial balance

in the school, there are a number of factors which can

have a positive effect on black adult achievement?

A. Yes.

Q. What are those things?

A. Uhm, -

Q. Occupational training?

[p. 1068] A. Yes.

Q. Personal Character?

A. Yes.

Q. Socioeconomic status?

A. Yes.

461

Q. Parental support again?

A. Yes,

Q. There are a number of factors; right?

A. Yes. Yes.

Q. And, would you agree that blacks can achieve

and become successful when these factors come into play

even though they attend schools that are not racially

balanced?

A. Yes.

* * *

[p. 1078] Q. * * * do I understand you correctly that

when all factors remain constant that the racial balance of

the school doesn't have an impact on black academic

achievement?

A. I'll agree with that.

* * 54-

[p. 1093] Q. Well, can you think of any activity

outside of school that would have a positive effect on

blacks?

A. Sure. Playing games on the same team.

Q. Okay. Anything else?

A. Being in Boy Scouts together.

Q. Anything else?

Q. Okay.

A. Going to after-school tutoring together.

462

A. Going to church together, or Sunday School, I

mean. Not church. Those are things that come to mind.

Q. So you will admit that there are interactions

between black students and white students outside of the

classroom which, in your opinion, are beneficial to the

blacks?

A. Yes.

Q. And allow them to become socially acceptable

when they - when they get out of school.

A. Let me just re— I don't know quite what you

mean by socially acceptable. You mean they've learned

how to act so they're socially acceptable to white people?

Is that what you meant?

Q. Well, that was a poor choice of words on my

part.

The point I was trying to make is, as a result of this

interaction, they could better socialize with whites when

they become adults.

A. Yes, it would be helpful.

H* Jfr Jfr

[p. 1097] Q. So all other factors that determine black

adult success will be favorably impacted by virtue of

busing the children between grades five and twelve?

A. That's correct.

Q. And there will be positive benefits sustained and

received by those children at those grade levels?

A. That's right. I believe that's true. Yes.

463

Q, You also testified that, in your opinion, black -

all-black colleges are okay.

A. Yes.

Q. And they produce some - some black scholars.

A. Sure.

Q. But you made the distinction that those are dif

ferent from elementary schools because it's not manda

tory to go to a black college. Is that what you said?

A. Yes. It's not mandatory to go to college at all.

Q. But it is mandatory to go to school.

A. That's right.

Q. Are you aware that in Oklahoma City it is not

mandatory to got to a black elementary school?

A. Oh, yes. I know that.

* * *

YALE RABIN

[p. 1125] THE COURT: Wait, w hat's the

number?

MR. CHACHKIN: Plaintiff's exhibit number 60.

THE COURT: 60?

MR. CHACHKIN: With the overlay, plaintiff's

exhibit 58-A, over it.

Q. (BY MR. CHACHKIN:) Would you describe what

this map is?

A. This map is the distribution of black population

by block, 1970.

464

If I may, I think I should explain the notion of block

so that it's clearly understood what the distinction is

between a block and a tract.

A census tract is the largest, most conventional unit

of data gathering which the census bureau uses, but each

tract is divided, depending on whether it's in a rural or

an urban area. If it's in a rural area, a tract is subdivided

into what are called an enumeration district, an enumera

tion district literally being the area that's covered during

the census by a single enumerator.

In Urban areas, the census tract is divided into

blocks, and blocks are - generally correspond to city,

individual city blocks, that is, an area of land bounded by

four streets, or three streets and a railroad, or a river, but

there are clearly evident boundaries to the block itself.

[p. 1126] So we're talking about a great many subdi

visions within a census tract. There may be as many as

100 or 200 blocks within an individual census tract. So

that this provides a far more precise indication of where

people live within the tract than one which deals with the

tract in aggregate.

Q. So that's -

A. So that this map then shows that distribution,

population by race, by block, for 1970, with the color

designations being precisely the same as they were on the

1960 map.

Q. And this map was prepared under your supervi

sion?

A. Yes, it was.

465

A. I have. Yes.

Q. Are you satisfied with the work done by your

graduate student?

A. I am.

Q. Would you briefly describe the distribution of

black population in 1970 as shown on the map?

A. Yes. As the map indicates/ there has been a j prv

substantial increase in the area in which blacks livm and

\ evidence of some dispersal of blacks to areas of the city in

which they did not live before.

C Most of the direction in which that change has taken

place has been to the north and east, but there are some

/ evidence of small changes that are taking place else-

' where.

Q. And have you checked it for accuracy?

[p. 1127] It may not be visible, but there are blocks in

the southwest that now begin to show up as having more

than ten percent black population in 1970.

But predominantly the growth is from the areas

which were black in 1950. They have expanded in size,

and that expansion has taken place largely to the north.

And the other changejhat I ..would note that's taken

place is that there is also an increase in the intensity, that

is. the degree to which the larger black areas are black.

That is, one

what I will call the central

Q. I believe it's been referred to as the northeast

quadrant.

466

A. The northeast quadrant. And I don't know how

the area further east is characterized, but both of them