Wallace Contempt Suit (Telegram)

Press Release

September 22, 1966

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 4. Wallace Contempt Suit (Telegram), 1966. 13f20833-b792-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c901831e-08f8-4621-8624-f9a01d72337a/wallace-contempt-suit-telegram. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

Fa eck arsitd

a a a a oh Ts Bites

Z INTERNATIONAL SERVICE

Uae ee aoe 4

4» 7_pomestic service \ $

© | Cheek the class ofvervice desired Check the class of seevicedesired

otherwise this message will be otherwise the message will be

sent asa fast telegram $ sent at the full rate

FULL RATE TELEGRAM ry 2211 (4-55)

[eo wos-cu oF sve. | Poor cou, | CASH NO. Te _- ,sOMARGE TO THE ACCOUNT OF T TIME FILED 1

ae Legal Defense & Ed. evae a4

10 Columbus Circle, NYC

Send the following message, subject co che terms on back hereof, which are hereby agreed to

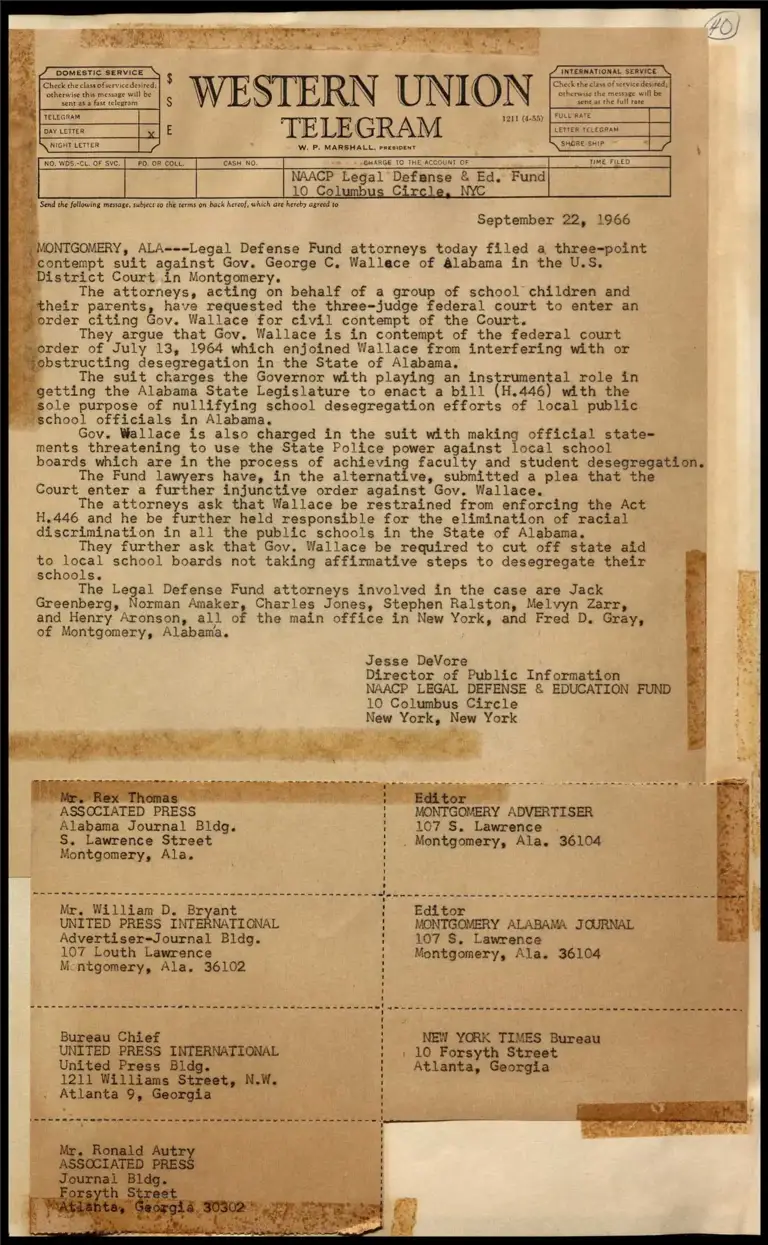

September 22, 1966

INTGOMERY, ALA=+-Legal Defense Fund attorneys today filed a three-point

ontempt suit against Gov. George C. Wallece of Alabama in the U.S,

District Court in Montgomery.

a The attorneys, acting on behalf of a group of school children and

their parents, have requested the three-judge federal court to enter an

rder citing Gov. Wallace for civil contempt of the Court.

5 They argue that Gov. Wallace is in contempt of the federal court

rder of July 13, 1964 which enjoined Wallace from interfering with or

bstructing desegregation in the State of Alabama.

The suit charges the Governor with playing an instrumental role in

etting the Alabama State Legislature to enact a bill (H.446) with the

ole purpose of nullifying school desegregation efforts of local public

chool officials in Alabama.

Gov. Wallace is also charged in the suit with making official state=

ments threatening to use the State Police power against local school

boards which are in the process of achieving faculty and student desegregation.

The Fund lawyers have, in the alternative, submitted a plea that the

Court enter a further injunctive order against Gov. Wallace.

The attorneys ask that Wallace be restrained from enforcing the Act

H,.446 and he be further held responsible for the elimination of racial

discrimination in all the public schools in the State of Alabama.

They further ask that Gov. Wallace be required to cut off state aid

ee school boards not taking affirmative steps to desegregate their

schools.

The Legal Defense Fund attorneys involved in the case are Jack

Greenberg, Norman Amaker, Charles Jones, Stephen Ralston, Melvyn Zarr,

and Henry Aronson, all of the main office in New York, and Fred D. Gray,

of Montgomery, Alabama.

Jesse DeVore

Director of Public Information

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATION FUND

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

se ate

MONTGOMERY ADVERTISER

107 S. Lawrence .

. Montgomery, Ala. 36104

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Alabama Journal Bldg.

S. Lawrence Street

Montgomery, Ala.

Mr, William D. Bryant

UNITED PRESS INTERNATIONAL

Advertiser-Journal Bldg.

107 Louth Lawrence

Mcntgomery, Ala. 36102

MONTGOMERY ALABAMA JOURNAL

107 S. Lawrence

Montgomery, Ala, 36104

M

i

e

w

i

e

e

a

sw

an

ee

si

et

s

oe

s

L

u

‘ 1 5 ' 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 4 , ' t ‘ 1 1 2 1 n , r 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ‘ ‘ , ’ ‘ ‘ 1 1 ' ‘ 1 1 y 4 1 1 1 :

NEW YORK TIMES Bureau

| 10 Forsyth Street

Atlanta, Georgia

ee Chief

UNITED PRESS 11

United Press Bi

211 Willi

. Atlanta 9,