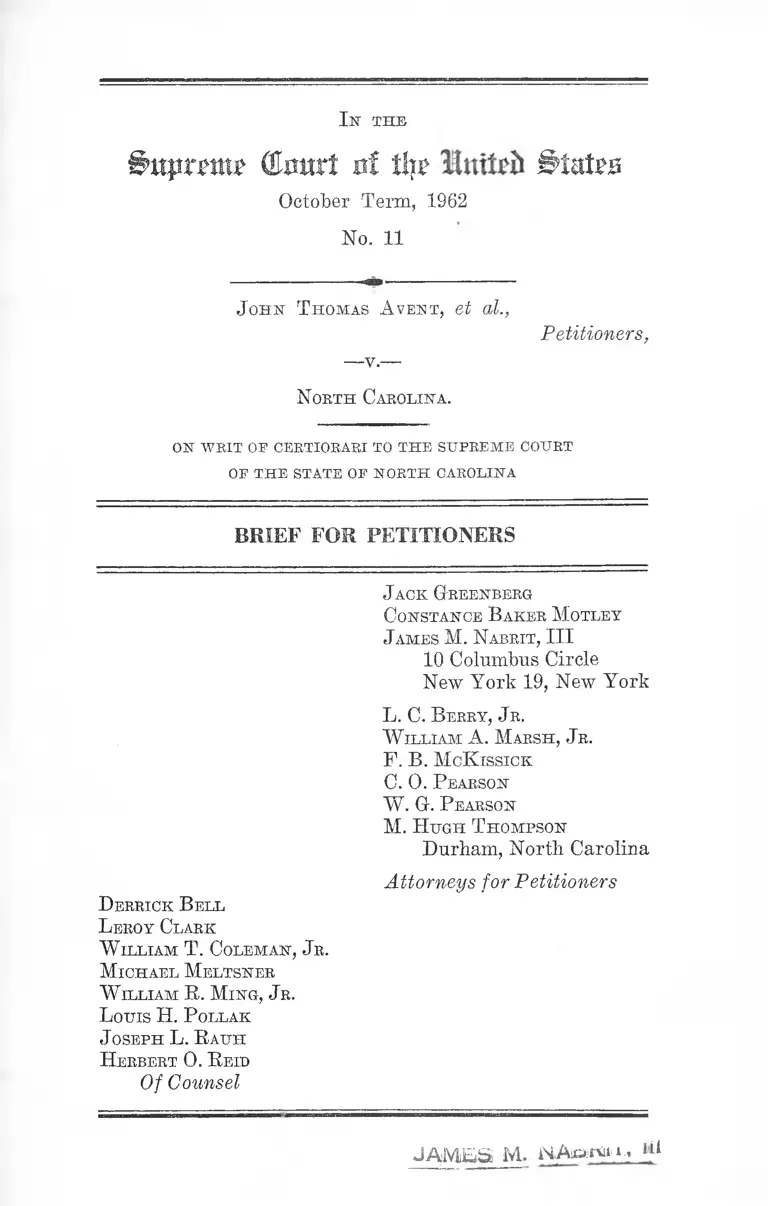

Avent v. North Carolina Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Avent v. North Carolina Brief for Petitioners, 1962. 34dd2d7f-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c9065788-ecb4-44ed-8c64-0e86195de608/avent-v-north-carolina-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I kt t h e

%>uptmt (Emit iif % States

October Term, 1962

No. 11

J ohn Thomas A vent, et al.,

Petitioners,

-- y.---

N orth Carolina.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker Motley

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

L. C. B erry, J r.

W illiam A. Marsh, J r.

F. B. McK issick

C. 0 . P earson

W. G. P earson

M. H ugh Thompson

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

D errick B ell

Leroy Clark

W illiam T . Coleman, J r .

Michael Meltsner

W illiam R . Ming, J r .

Louis H. P ollak

J oseph L. R auh

H erbert 0 . R eid

Of Counsel

JAMBS M. NAaartM-. lU

INDEX

PAGE

Opinion Below................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction...................................................................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved..... 2

Questions Presented........................................................ 2

Statement ............................................................ 4

Summary of Argument........ ......................................... 8

A rgument

I. North Carolina in Enforcing What Its Highest

Court Has Denominated a “Clear Legal Eight

of Racial Discrimination” Has Denied to Peti

tioners the Equal Protection of the Laws Se

cured by the Fourteenth Amendment ............... 12

A. Arrest, Conviction, and Sentence to Prison

for Trespass for Having Violated the S. H.

Kress Co.’s Requirement of Racial Segrega

tion at Its Public Lunch Counter Deny Peti

tioners the Equal Protection of the Laws

Secured by the Fourteenth Amendment...... 12

B. Certainly, at Least, the State May Not by

Its Police and Courts Enforce Such Segre

gation When It Stems From a Community

Custom of Segregation Which Has Been

Generated bĵ State Law.................. ............. 17

n

PAGE

C. A Fortiori, the State May Not Arrest and

Convict Petitioners for Having Violated a

Segregation Rule Which Stems Prom a State

Generated, Community Custom of Segrega

tion in Premises in Which the State Is

Deeply Involved Through Its Licensing and

Regulatory Powers....................................... 24

D. No Essential Property of S. H. Kress and

Co. Is Here at Issue; the Right to Make

Racial Distinctions at a Single Counter in

a Store Open to the Public Does Not Out

weigh the High Purposes of the Fourteenth

Amendment.................................................... 27

E. In Any Event the Convictions Below Must

Pall When, in Addition to the Foregoing,

North Carolina Has Failed to Protect Negro

Citizens in the Right to Equal Access to

Public Accommodations .............................. 35

II. The Criminal Statute Applied to Convict Peti

tioners Gave No Fair and Effective Warning

That Their Actions Were Prohibited: Peti

tioners’ Conduct Violated No Standard Re

quired by the Plain Language of the Law;

Thereby Their Conviction Offends the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

and Conflicts With Principles Announced by

This Court........................................................... 39

III. The Decision Below Conflicts With Decisions of

This Court Securing the Fourteenth Amend

ment Right to Freedom of Expression....... ...... 47

Conclusion ............ 51

V

PAGE

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350' U. S. 879 ............................. ...... 12

Holmes v. Connecticut Trust & Safe Deposit Co., 92

Conn. 507, 103 Atl. 640 (1918) ............................... .. 29

Hudson County Water Co. v. McCarter, 209 U. S.

345 ................................................................... ........... 34

Klor’s Inc. v. Broadway-Hale Stores, 359 TJ. S. 207

(1959) ......................................................................... 31

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77 ................................... 16

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 ................................ 46

Lane v. Cotton, 1 Ld. Raym. 646, 1 Salk. 18, 12 Mod.

472, 485 ...................................................................... 32

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 ................. 41, 42, 44

Levitt & Sons, Inc. v. Division Against Discrimination,

31 N. J. 514, 158 A. 2d 177 (1960) ............................ 31

Lorain Journal Co. v. United States, 342 U. S. 143

(1951) ......................................................................... 31

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 ....................................... 44

Lynch v. United States, 189 F. 2d 476 (5th Cir. 1951) .... 35

Maddox v. Maddox, Admr., 52 Va. 804 (1954) ....... . 29

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 .......................................... 17

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 ........................28, 34,47

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141.............. ..........16, 48, 49

Massachusetts Comm’n Against Discrimination v. Col-

angelo, 30 U. S. L. W. 2608 (Mass. 1962) ................. 31

Mayor, etc. of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877 ..... 12

McBoyle v. United States, 283 U. S. 25 .....................43, 45

Miller v. Schoene, 276 U. S. 272 (1928) ..................... 32

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167....................................... 13

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 ...... ............ ............ 20

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 347 U. S. 971,

vacating and remanding, 202 F. 2d 275 ..................... 13

VI

PAGE

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ...... ..................24, 42, 49

Nashville C. & St. L. Ry. v. Browning, 310 U. S. 362 .... 18

New Orleans City Park Improvement Assn. v. Detiege,

358 U. S. 5 4 ................................................................ 12

N. Y. State Comm’n Against Discrimination v. Pelham

Hall Apts. Inc., 10 Misc. 2d 334, 170 N. Y. S. 2d 750

(Snp. Ct. 1958)............................................................. 31

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 ................................... 26

N.L.R.B. v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d 258

(8th Cir. 1945) ............................................................. 48

N.L.E.B. v. Babcock & Wilcox Co., 351 U. S. 105 (1955) 33

N.L.R.B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U. S. 240 ......... 48

People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934 (1948) ........................ 49

Pierce v. United States, 314 U. S. 306 ........ 42

Poe v. Ullman, 367 U. S. 497 ....................................... 18

Pollock v. Williams, 322 U. S. 4 ................................... 23

Porter v. Barrett, 233 Mich. 373, 206 N. W. 532 (1925) 30

Public Utilities Commission v. Poliak, 343 U. S.

451...................................... ........................................ 17, 26

Queenside Hills Realty Co. v. Saxl, 328 U. S. 80 (1946) 32

Railway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88..................... 27

In Re Ranney’s Estate, 161 Misc. 626, 292 N.. Y. S. 476

(Surr. Ct. 1936) ......................................................... 29

Republic Aviation Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 324 U. S. 793

(1945) ................ 28,33,47-48

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 ................................... 46

St. Louis Poster Advertising Co. v. St, Louis, 249 U. S.

269 (1919) ....................... 33

Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 47 ......................... 50

Schmidinger v. Chicago, 226 U. S. 578 ............................ 33

V II

PAGE

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91.............................. 13

Semler v. Oregon State Board of Dental Examiners,

294 U. S. 608 (1935) .................................................. 33

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ..............12,14, 28, 30, 33, 35

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147............................. ...... 46

State Athletic Comm’n v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533 .......... 13

State Comm’n Against Discrimination v. Pelham Hall

Apartments, 10 Misc. 2d 334,170 N. Y. S. 2d 750 (Snp.

Ct. 1958) ...................................................................... 31

State of Maryland v. Williams, 44 Lab. Bel. Bef. Man.

2357 (1959) .................................................................. 49

State v. Clyburn, 247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. 2d 295

(1958)......................................................................... 21, 40

State v. Johnson, 229 N. C. 701, 51 S. E. 2d 186 (1949) 21

Stanb v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313...................................... 42

Steele v. Louisville and Nashville B.R, Co., 323 U. S.

192.................................................................. 26

Stromberg v. Calif., 283 U. S. 359 ................................44, 49

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154...................... ....... . 13

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461 ....................................... 35

Thomas Cusack Co. v. Chicago, 242 U. S. 526 (1917) 33

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199............. 41

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88................ ............... 49

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312 ...... .................... ...... 35

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ....... .... ....................... 13

United States v. Addyston Pipe & Steel Co., 85 Fed. 271

(6th Cir. 1898) aff’d 175 U. S. 211 (1899) ............... . 30

United States v. Beaty, 288 F. 2d 653 (6th Cir. 1961) .... 33

United States v. Cardiff, 344 U. S. 174 .......... ...........42, 43

United States v. Colgate, 250 U. S. 300 (1919) ............ . 31

United States v. Hall, 26 Fed. Cas. 79 ...... .............. . 36

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81 ....43, 44

V l l l

PAGE

U. S. v. Parke, Davis & Co., 362 U. S. 29 (1960) .......... 31

United States v. Weitzel, 246 U. S. 533 .....................43, 44

United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U. S. (5 Wheat.) 76 .... 43

United Steelworkers v. N.L.R.B., 243 F. 2d 593 (D. C.

Cir., 1956) (Reversed on other grounds), 357 U. S. 357 48

Watehtower Bible and Tract Soc. v. Metropolitan Life

Ins. Co., 297 N. T. 339, 79 N, E. 2d 433 (1948) ......... 16

Western Turf Assn. v. Greenberg, 204 U. S. 359 ......... 27

Winterland v. Winterland, 389 111. 384, 59 N. E. 2d

661 (1945) .............................. ...................................... 29

Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25 ....................................... 17

F edekal S tatutes

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27 ............................ 16

Civil Rights Act of 1875 .............................................. 37

Civil Rights Act of 1875, 18 Stat. 335 ......................... 16

Clayton Act, 15 U. S. C. §12, et seq.............................. 30

Miller-Tydings Act amendment of §1 of the Sherman

Act, 15 U. S. C. § 1 ..................................................... 30

Robinson-Patman Act, 15 U. S. C. §13 et seq................ 30

Sherman Anti-Trust Act, 15 U. S. C. §1 et seq............. 30

United States Code, Title 28, §1257(3) ......................... 1

United States Code, Title 42, §1981 ............................ 15

United States Code, Title 42, §1982 ............................ 15

S tate S tatutes

Ark. Code Sec. 71-1803 .................................................. 45

Cal. Civil Code, §51 (Supp. 1961) ................................ 31

Cal. Civ. Code, sections 51-52 (Supp. 1961) ...... .......... 31

IX

PAGE

Cal. Health & Safety Code (See. 35740) .............. ...... 31

Code of Ala., Title 14, Sec. 426 ................................... 45

Code of Virginia, 1960 Replacement Volume, Sec. 18.1-

173 ............................................................................... 45

Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. sections 25—1—1 (1953).............. 31

Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. sections 69-7-1 (Supp. 1960) ...... 31

Conn. Hen. Stat. Rev. §53-35 (Supp. 1960) ................. 31

Conn. Gen. Stat. Rev. sec. 53-35 (Supp. 1961) .............. 31

Conn. Gen. Stat. Rev. sections 53—35-36 ................ 31

Conn. Stat. Rev. §53-35-35 .............................................. 31

Conn. Gen. Stat. (1958 Rev.) sec. 53-103 ..................... 45

Constitution of North Carolina, Art. XIV, sec. 8

(1868) ......................................................................... 21

D. C. Code, sec. 22-3102 (Supp. VII, 1956) ................. 45

D. C. Code Ann. sections 47—2901-04 (Supp. 1960) .... 31

Florida Code, sec. 821.01 ........................... ................... 45

Hawaii Rev. Code, sec. 312-1 ....................................... 45

Illinois Code, sec. 38-565 ........... 45

Indiana Code, sec. 10-4506 ........................................... 45

Indiana Stat., secs. 10-901, 10-902 (Supp. 1962) .......... 31

Iowa Code Ann. sections 735.1-02 (1950) ..................... 31

Kansas Gen. Stat. Ann. sections 21-2424 (1949) .......... 31

Laws of Alaska Ann. 1958 (compiled), Cum. Supp.

Vol. Ill, sec. 65-5-112................ ................................. 45

Mass. Code Ann. c. 266, sec. 120 ................................ 45

Mass. G. L. c. 151B, §§1, 4, 6 (Supp. 1961) ................. 31

Mass. G. L. (Ter. Ed.) c. 272, sections 92A, 98 (1956),

c. 151B, sections 1-10.................................................. 31

Mich. Stat. Ann. 1954, Vol. 25, Sec. 28.820(1) ............ 45

Mich. Stat. Ann. §28-343 (Supp. 1959)............................ 31

X

PAGE

Minn. Stat. Ann. section 327.09 (1947) ........................ 31

Minn. Stat. Ann., 1947, Vol. 40, sec. 621.57 ................. 45

Minn. Stat. Ann. §§363.01-.13, as amended by L. 1961,

c. 428 to become effective 12/31/62 ......................... 31

Mississippi Code, sec. 2411 ........................................... 45

Montana Rev. Codes Ann. section 64-211 (Supp. 1961) 31

Neb. Rev. Stat. sections 20-101, 102 (1943) ................. 31

Nevada Code, sec. 207.200 ............................................ 45

N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§354.1-4, as amended by L. 1961,

c. 219 ........................................................................... 31

N. C. Gen. Stat., sec. 14-126........................................... 40

N. C. Gen. Stats., sec. 14-134 ................................2, 4, 39,40

N. C. Gen. Stat. sec. 14-234 ........................................... 40

N. C. G. S. 14-181............................................................. 21

N. C. G. S. 51-3 ............................................................. 21

N. C. G. S. §55-79 ......................................................... 25

North Carolina General Statutes, sec. 55-140 .............. 25

N. C. G. S. 58-267 ......................................................... 21

G. S. 60-94 to 9 7 ............................................................. 20

N. C. G. S. 60-135 to 137 .............................................. 20

N. C. G. S. 60-139 ......................................................... 21

N. C. G. S. 62-44 ............................................................ 20

N. C. G. S. 62-127.71 ..................................................... 20

N. C. G. S. 65-37 ............................................................ 19

N. C. G. S. 72-46 ..... 21

N. C. G. S. 90-212 ...... 20

N. C. G. S. 95-48 ............................................... 21

N. C. G. S. §105-62 ..................................................... 25

N. C. G. S. §105-82 ........................................................ 25

N. C. G. S. §105-98 ..................................................... 25

N. C. G. S. §105-164.4-6 ........... 25

N. C. G. S. 105-323 .............. 19

N. C. G. S. 116-109.......................... 19

PAGE

xi

N. C. G. S. 116-120............................................... 19

N. C. G. S. 116-124..................................................... 19

N. C. G. S. 116-138 to 142.............................................. 19

N. C. Gr. S. 122-3-6 ............................................... 19

N. C. Gr. S. 127-6............................................................. 19

N. C. Gr. S. 134-79 to 84 .................................................. 19

N. C. G-. S. 134-84.1 to 84.9 ....................... 19

N. C. G. S. 148-43 ......................................................... 19

N. C. Gen. Laws, Cli. 130 (1957) ................ 25

N. D. Cent. Code, section 12-22-30 (Snpp. 1961) ... ......... 31

N. J. Stat. Ann. sections 10:1—2-7, section 18:25—5

(Snpp. 1960) .............................................................. 31

N. J. Stat. Ann. sec. 18:25-4 (Snpp. 1961) ................... 31

N. M. Stat. Ann. sections 49—8—1-6 (Supp. 1961) ........ 31

1ST. Y. Civil Eights Law, section 40-41 (1948), Execu

tive Law, sections 292(9), 296(2) (Snpp. 1962) ...... 31

N. Y. Executive Law, §§290-99 as amended by L. 1961,

c. 414 ......... 31

Ohio Code, sec. 2909.21 .............................................. 45

Ohio Eev. Code, sec. 4112.02(G) (Supp. 1961) .......... 32

Oregon Code, sec. 164.460 ........................ ..... ................ 45

Ore. Eev. Stat. sections 30.670-680, as amended by Sen

ate Bill 75 of the 1961 Oregon Legislature .............. 32

Ore. Eev. Stat. sec. 659.033 (1959) ................................ 31

Pa. Stat. Ann. Tit. 18, section 4654, as amended by

Act No. 19 of the 1961 Session of Pa. Gen. Assembly 32

Pa. Stat. Ann. Titl. 43, §§951-63, as amended by Acts

1961, No. 19 ............................................... 31

E. I. Gen. Laws Ann. sections 11-24-1 to 11-24-1-6

(1956) ......... 32

Vermont Stat. Ann. tit. 13, Sections 1451-52 (1958) .... 32

XU

PAGE

Wash. Eev. Code §49.60.030 (1957) ................................ 31

Wash. Eev. Code, Section 49.60.040 (1957) ................. 31

Wash. Eev. Code, Sections 49.60.040, 49.60.215 (1962) 32

Wis. Stat. Ann. Section 942.04 (1958) as amended

(Supp. 1962)................................................................ 32

Wyoming Code, Sec. 6-226 .............................................. 45

Wyoming Stat., Sections 6-83.1, 6-83.2 (Supp. 1961) .... 32

City Ordinances

Burlington Code, Sec. 8-1 ....................... 20

Charlotte City Code, Article I, Sec. 5 .......................... 20

Charlotte City Code, Ch. 7, Sec. 7-9, 7-56....................... 20

Lumberton Code, Sec. 7-19 .......................................... 20

Winston-Salem Code, Sec. 6-42............................... 20

E nglish S tatutes

Statute of Labourers, 25 Ed. Ill, Stat. I (1350) ..... 32

(1464), 4 Ed. IV., c. 7 .............................................. 32

(1433), 11 H. VI, c. 1 2 ....................................... 32

(1357), 31 Ed. Ill, c. 10............................................... 32

(1360), 35 Ed. I l l ......................................................... 32

Other A uthorities

Abernathy, Expansion of the State Action Concept

Under the Fourteenth Amendment, 43 Cornell L Q

375 .............................................................................. 38

Adler, Business Jurisprudence, 28 Harv. L. Eev 135

(1914) ......................................................................... 32

a n

PAGE

A. L. I., Restatement of the Law of Property, Div. 4,

Social Restrictions Imposed Upon the Creation of

Property Interests (1944), p. 2121.............. ......... 29,30

A. L. I., Restatement of Torts, §867 (1939) ............... 17

Ballentine, “Law Dictionary” 436 (2d Ed. 1948) ........ 45

Beale, The Law of Innkeepers and Hotels (1906) ...... 32

“Black’s Law Dictionary” (4th Ed. 1951) 625 ............. 45

4 Blackstone’s Commentaries, Ch. 13, sec. 5(6) Wen

dell’s Ed. 1850 ..................................... ............. u

Blodgett, Comparative Economic Systems 24 (1944) .... 28

Browder, Illegal Conditions and Limitations: Miscel

laneous Provisions, 1 Okla. L. Rev. 237 (1948) ...... 30

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong. 2d Sess. p. 3611 (1870) .......... 37

Cong. Globe, 42d Congress, 1st Sess., p. 459 .............. 37

Cong. Globe, 42d Congress, 1st Sess., p. 483 (1871) .... 36

Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess., 383 ....................... . 17

Appendix to the Cong. Globe, 42d Congress, 1st Sess.

p. 8 5 ............................................................. 37

Cong. Rec., 43d Cong., 1st Sess. 412 (1874) ................. 37

County of Durham Sanitary Code ......... ................... 25

Equal Protection of the Laws Concerning Medical

Care in ..North Carolina, Subcommittee on Medical

Care of the North Carolina Advisory Committee to

the United States Commission on Civil Rights (un-

dated) ......................................-.........-.... -__ _____ 19,20

Gray, Restraints on the Alienation of Property 2d ed

1895, §259 ...................................................... __........ ' 30

Gray, The Rule Against Perpetuities, §201, 4th ed.,

Hale, Force and the State: A Comparison of “Politi

cal” and “Economic” Compulsion, 35 Colum. L Rev

149 (1935) ........................ .......... _____ 38

XIV

PAGE

Konvitz & Leskes, A Century of Civil Rights, 150

(1961) ...................................................................... 27,38

Leach, Perpetuities in a Nutshell, 51 Harv. L. Rev. 638

(1938) ......................................................................... 30

Mund, “The Right to Buy—And Its Denial to Small

Business,” Senate Document #32, 85th Cong. 1st

Sess., Select Committee on Small Business (1957) .. 32

North Carolina Advisory Committee Report 18.......... 21

North Carolina Advisory Committee to the United

States Commission on Civil Rights, Statutes and

Ordinances Requiring Segregation by Race, 23

(March 9, 1962) ........................................................ lg? 21

Poliak, Racial Discrimination and Judicial Integrity:

A Reply to Professor Wechsler, 108 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1

(1959)........ 38

6 Powell, Real Property, 1J851, Restatement of Prop

erty, §424 (1944) ......................................................... 29

Rankin, The Parke, Davis Case, 1961 Antitrust Law

Symposium, New York State Bar Association Sec

tion on Antitrust Law 63 (1961) ................................ 31

State Board of Health Laws, Rules and Regulations .. 25

United States Commission on Civil Rights, “The Fifty

States Report” 477 (1961) ......................................... 19

Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow 47

(1955) ........................................................................22,23

I n t h e

& u p r m ? ( t a r t n t t l |? 'MixlUb J ita tT is

October Term, 1962

No. 11

J ohn Thomas A vent, el al.,

—v.—

Petitioners,

N orth Carolina.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

(R. 73) is reported at 253 N. C. 580, 118 S. E. 2d 47 (1961).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

was entered January 20, 1961 (R. 90). On April 4, 1961,

time for filing a petition for writ of certiorari was extended

by the Chief Justice to and including May 4, 1961 (R. 91).

The petition was filed on that date. June 25, 1962, the peti

tion for writ of certiorari was granted (R. 92). Jurisdiction

of this Court is invoked pursuant to Title 28 United States

Code Section 1257(3), petitioners having asserted below

2

and claiming here, denial of rights, privileges, and immuni

ties secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves North Carolina General Stat

utes, §14-134:

Trespass on land after being forbidden. If any person

after being forbidden to do so, shall go or enter upon

the lands of another, without a license therefor, he

shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and on conviction,

shall be fined not exceeding fifty dollars or imprisoned

not more than thirty days.

Questions Presented

Petitioners have been arrested, convicted, and sentenced

to prison for refusal to obey an order to leave the lunch

counter in a store open to the public, including Negroes.

This order was given to enforce a custom of the community,

generated by a massive body of state segregation law. The

premises are extensively licensed and regulated by the

State of North Carolina and the City of Durham. North

Carolina has failed to accord Negroes the right of equal

access to public accommodations.

I.

A. May North Carolina, compatibly with the Fourteenth

Amendment, make petitioners the target of a prosecution

under its trespass laws when the articulated rationale of

3

the prosecution is, according to North Carolina’s highest

court, to enforce “the clear legal right of racial discrimina

tion” of the S. H. Kress Corporation!

B. Are not these criminal trespass prosecutions, in any

event, incompatible with the Fourteenth Amendment be

cause they constitute purposeful state enforcement of a

custom of racial discrimination—a custom which is itself

the carefully nurtured fruit of decades of segregation re

quired by state law!

C. Is not the degree of supervision and control which

the State of North Carolina and the City of Durham ex

ercise over the S. H. Kress lunch counter business so ex

tensive a form of state involvement that, given the circum

stances of A and B, supra, North Carolina has failed in

its obligation to afford equal protection of the laws!

D. In addition to considerations set forth above, is not

the property right which S. H. Kress and Co. has asserted

—the right to discriminate racially in a single portion of a

store open to the general public—so inconsequential to the

main core of its proprietary interest, that the State may

not compatibly with the Fourteenth Amendment, enforce

that right by its criminal laws!

E. In view of the fact that North Carolina denies pro

tection to Negroes against racial discrimination in public

accommodations, do not the circumstances set forth above

establish a denial of equal protection of the laws!

II.

The trespass statute under which petitioners were con

victed forbids only entry without license. Petitioners were

invited to do business in the store and were ordered to

4

leave only because they sought nonsegregated service at

the lunch counter, the only racially segregated counter in

the store. The North Carolina Supreme Court has for the

first time unambiguously held that the statute under which

petitioners were convicted makes criminal refusal to leave

after an invitation to enter. Does not this conviction, there

fore, violate the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment in that the statute upon which it rests gave

petitioners no fair and effective warning that their actions

were prohibited?

III.

Is not North Carolina denying petitioners freedom of

speech secured by the Fourteenth Amendment by using

its criminal trespass laws as a device to stop petitioners

from urging S. H. Kress and Company to abandon its

discrimination practices ?

Statem ent

Petitioners, five Negro students from North Carolina

College and two white Duke University students, were

arrested for a “sit-in” demonstration at the S. II. Kress

Department store lunch counter in Durham, North Carolina

(K. 20-21). They were charged with trespass under North

Carolina General Statutes, Chapter 14, Section 134, which

prohibits going or entering upon land after being forbidden

to do so (R. 1-10).

On May 6, 1960, petitioners, some of whom in the past

had been regular customers, bought small stationery items

at counters on the first floor of the Kress Department Store

(R. 35, 39, 41-43, 46, 47, 48). Negroes and whites were

served without discrimination in all fifty departments ex-

5

cept at the lunch counter portion where patrons sit (R. 22-

23). There Negroes were barred, although a “stand-up”

section serviced whites and Negroes together (R. 22-23).

After making their purchases, petitioners proceeded to the

basement through the normal passageway bordered by an

iron railing, and took seats at the lunch counter (E. 37, 40,

42, 44, 46, 47, 48). No signs at any entranceway or counter

barred or limited Negro patronage (R. 22-23). A sign in

the basement luncheonette limited it to “Invited Guests

and Employees Only” (R. 23). No further writing eluci

dated its meaning; but the manager testified that while

invitations were not sent out, white persons automatically

were considered guests, but Negroes and whites accom

panied by them were not (R. 22).

The racial distinction was based solely on the custom

of the community: The manager testified, “It is the policy

of our store to wait on customers dependent upon the

custom of the community . . . It is not the custom of the

community to serve Negroes in the basement luncheonette,

and that is why we put up the signs ‘Invited Guests and

Employees Only’” (R. 23). He further stated that if

Negroes wanted service, they might obtain it at the back

of the store or at a stand-up counter upstairs (R. 22).

As petitioners took seats, the manager approached and

asked them to leave (R. 21). One petitioner, Joan Nelson

Trumpower, a white student, had already received and

paid for an order of food (R. 42). When she attempted to

share it with Negroes on either side of her, the manager

asked her to leave (R. 23, 42). He never identified himself,

however, as the manager or as a person with authority

to ask them to leave (R. 42).

While petitioners remained seated awaiting service, the

manager called the police to enforce his demand (R. 21).

6

An officer promptly arrived and asked them to leave (E.

21). Upon refusal the officer arrested them for trespass

(R. 21). At all times petitioners were orderly and, when

arrested, offered no resistance (R. 22, 26).

Petitioners were members of an informal student group

with a program of protesting segregation (R. 36, 41, 43,

44). They had organized and led picketing at the store to

protest its policy of fully accepting the business of Negro

patrons while refusing them service at the sit-down lunch

counter (R. 36, 40-41, 44-45). The picketing occurred at

various times from February 1960 until the arrest on

May 6, 1960 (R. 44). Some of the petitioners had requested

and had been denied service on previous occasions at the

lunch counter, and on the day of the arrests, they con

tinued to request service in hope that their protests would

be successful (R. 37, 40-41, 49). On the previous day peti

tioners attended a meeting to discuss the sit-in demonstra

tions, where it was agreed that they would trade in the

store as customers as in the past, and then seek service

on the same equal basis at the lunch counter (R. 49).

They were indicted for trespass in the Superior Court

of Durham County, the indictments stating that each peti

tioner

“with force and arms . . . did unlawfully, willfully,

and intentionally, after being forbidden to do so, enter

upon the land and tenement of S. H. Kress and Co.,

store . . . said S. IT. Kress and Co., owner being then

and there in actual and peaceable possession of said

premises under the control of its manager and agent,

W. K. Boger, who had, as agent and manager, the

authority to exercise his control over said premises,

and said defendant after being ordered by said W. K.

Boger, agent and manager of said owner, S. H. Kress

7

and Co., to leave that part to the said store reserved

for employees and invited guests, willfully and unlaw

fully refused to do so knowing or having reason to

know that . . . [petitioner] had no license therefor,

against the form of the statute in such case made and

provided and against the peace and dignity of the

state.”

Each indictment identified each petitioner as “CM” (colored

male), “WM” (white male), “CF” (colored female), or

“WF” (white female) (E. 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10). Petitioners

made motions to quash the indictments raising defenses

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution. These were denied (E. 11-15). To the in

dictments they entered pleas of not guilty (E. 15).

Various federal constitutional defenses were made

throughout and at the close of trial, but were overruled

(E. 12, 15, 26-34, 50, 66-67). Petitioners were found guilty

(E. 15-16). Petitioners Coleman, Phillips, and CalLis Napo-

lis Brown were sentenced to 30 days imprisonment in the

common jail of Durham County to work under the super

vision of the State Prison Department (E. 17-18). Peti

tioner Streeter was sentenced similarly to 20 days (E. 19).

Petitioner A vent was sentenced to 15 days in the Durham

County jail (E. 16). Prayer for judgment was continued

in the cases of Shirley Mae Brown and Joan Harris Nelson

Trumpower (E. 16, 17).

Error was assigned again raising and preserving federal

constitutional defenses (E. 67-69), and the case was heard

by the Supreme Court of North Carolina, which affirmed

the convictions on January 20, 1961 (Clerk’s Certificate

following Court’s Opinion).

Summary of Argument

I.

The court below held that it was enforcing “the clear legal

right of racial discrimination of the owner.” But, while in

some circumstances there may be a personal privilege to

make racial distinctions, its limit is reached when the

person exercising it turns to the state for assistance. Judi

cial and police action are no less forbidden State action

when invoked to enforce discrimination initiated by an indi

vidual. Any suggestion that private rights, in the sense

that they invoke considerations of privacy, are involved is

farfetched. Kress’s has been open to the public in general.

The management did not assert the corporation’s own pref

erence for a segregation policy, but rather the custom of

the community. While considerations of privacy may be

meaningful in determining the reach of some constitutional

liberties, in this case the right to freedom from State im

posed racial discrimination is not in competition with any

interest the State might have in protecting privacy.

At the very least, however, the State may not enforce

racial discrimination which expresses deep-rooted public

policy. The record here conclusively shows that this is what

happened in this case. Such customs are a form of State

action. But beyond this the segregation customs in this

case were generated by a host of State segregation laws.

The North Carolina Advisory Committee to the United

States Commission on Civil Bights has concluded that, “so

long as these compulsory statutes are on the books, some

private citizens are more than likely to take it upon them

selves to try to enforce segregation.” Scholarship estab

lishes the crucial role which government, politics, and law

have played in creating segregation customs.

9

But the State-enforced, State-created community custom

of segregation in this ease is even more invidious because

it has taken place in an establishment in which the State

has been deeply involved by requiring extensive licensing

and regulation. State involvement in such an enterprise

precludes State enforcement of segregation therein by

means of arrests and prosecutions for trespass.

The holding below that the State merely was in a neutral

fashion enforcing an inalienable, sacred, property right is

clearly incorrect. States can, and have, constitutionally

forbidden property owners to discriminate on the basis of

race in public accommodations. North Carolina has not

inhibited itself from requiring racial segregation on private

property. The more an owner for his advantage opens his

property for use by the public in general, the more do his

rights become circumscribed by the constitutional and stat

utory rights of those who use it.

Property is a bundle of rights and privileges granted by

the State. That portion of the rights which constitute

Kress’s property, which Kress asserts here, and which the

State has enforced is to control the conduct and association

of others. This type of property right historically has never-

been unrestrained throughout the whole range of efforts

to assert it. Restraints on that power are but a manifesta

tion of the fact that law regularly limits or shapes property

rights where they may have harmful public consequences.

Other characteristics of the asserted right to racially dis

criminate in this case are that no claim of privacy has been

intruded upon; that petitioners sought only to use the prem

ises for their intended function; that segregation was re

quired only in a single part of an establishment open to the

general public, to which petitioners were admitted and in

which they were invited to trade freely except at the lunch

counter in question. This separable sliver in the entire

10

complex of powers and privileges which constitutes Kress’s

property is hardly entitled to legal protection when it col

lides with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, whose purpose was an end of discrimination

against the Negro.

Moreover, the Civil Rights Cases assumed that the State

law provided “a right to enjoy equal accommodations and

privileges . .. one of the essential rights of the citizen which

no state can interfere with.” The failure to provide such

rights can deny the equal protection of the laws. One mem

ber of the Court which decided the Civil Rights Cases pre

viously had written that denial included omission to pro

tect as well as the omission to pass laws for protection.

Legislators concerned with the scope of the Fourteenth

Amendment expressed similar views. The Civil Rights

Cases were decided on the assumption that the States in

question protected those rights. It is doubtful that the

result would have been the same if then, as today in North

Carolina, the States actively interfered with the right of

equal access to public facilities. No State may abdicate its

responsibilities by ignoring them; and where a State by its

inaction has made itself a party to the refusal of service and

has placed its power and prestige behind discrimination,

convictions such as those obtained in this case must fall.

II.

The statute applied to convict petitioners was unreason

ably vague and thereby offends the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment in that although the statute,

by terms, prohibits only the act of going on the land of

another after being forbidden to do so, the court below has

expansively construed the law to cover petitioners’ act of

remaining on the property after being directed to leave.

This strained construction of the plain words of the law

11

converts tlie common English word “enter” into a word of

art meaning “trespass” or “remain” and transforms the

statute from one which fairly warns against one act into a

law which fails to warn of conduct prohibited. The law is

invalid as its general terms do not represent a clear legis

lative determination to cover the specific conduct of peti

tioners, which is required where laws deter the exercise of

constitutional rights.

III.

The conviction violates petitioners’ right to freedom of

expression as secured by the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment against state infringement. Peti

tioners’ action here, a sit-in, is a well recognized form of

protest and was entirely appropriate to the circumstances,

including the use to which the privately owned property in

volved had been dedicated by the owner. There were no

speeches, picket signs, handbills, or other forms of expres

sion which might possibly be inappropriate to the time and

place. There was merely a request to be permitted to pur

chase goods in the place provided for such purchases. The

expression was not in such circumstances or of such a

nature as to create a clear and present danger of any sub

stantive evil the State had a right to prevent. The arrests

improperly stifled a protest against racial discrimination.

12

A R G U M E N T

I.

North Carolina in Enforcing What Its Highest Court

Has Denominated a “Clear Legal Right of Racial Dis

crimination” Has Denied to Petitioners the Etpial Pro

tection of the Laws Secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

A. Arrest, Conviction, and Sentence to Prison for Tres

pass for H aving Violated the S. H. K ress Co.’s R e

quirem ent o f Racial Segregation at Its Public Lunch

Counter D eny Petitioners the Equal Protection o f

the Laws Secured by the Fourteenth Am endm ent.

In affirming the conviction below the North Carolina Su

preme Court has twice said that it was merely enforcing

“the clear legal right of racial discrimination of the owner”

(R. 82, 83). One need turn no further than to Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, to see that it has been plain—if any

constitutional doctrine can be called plain—that there is

no “clear legal right of racial discrimination.” To the con

trary, while in some circumstances there may be a personal

privilege of making racial distinctions, the limit of that

privilege certainly is reached when the perspn exercising

it turns to state instrumentalities for assistance. Racial

discrimination is constitutionally inadmissible when “the

State in any of its manifestations has been found to have

become involved in it.” Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U. S. 715, 722.1

1 Segregation has been forbidden in schools, Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1; parks and

recreational facilities, Mayor, etc. of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 TJ. S.

877; Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879; New Orleans City Park

Improvement Ass’n v. Detiege, 358 U. S. 54; and airports, Turner

13

“ [I]t has never been suggested that state court action

is immunized from the operation of [the Fourteenth Amend

ment] . . . simply because the act is that of the judicial

branch of the state government.” Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. at 18. See also Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249;

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 499, 463. Police action

which segregates denies Fourteenth Amendment rights.

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154; Baldwin v. Morgan, 287

F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961); Boman v. Birmingham Transit

Co., 280 F. 2d 531, 533 n. 1 (5th Cir. 1960); see also Monroe

v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167; Screws v. United States, 325 U. S.

91. “Nor is the Amendment ineffective simply because the

particular pattern of discrimination, which the State has

enforced, was defined initially by the terms of a prior agree

ment. State action, as that phrase is understood for the

purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment, refers to exertions

v. Memphis, 369 TJ. S. 350; Henry v. Greenville Airport Comm’n,

284 F. 2d 631 (4th Cir. 1960).

Segregation requirements have been prohibited in privately

sponsored athletie contests, State Athletic Comm’n v. Dorsey, 359

U. S. 533; and in connection with privately owned transportation

facilities, Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903; Evers v. Dwyer, 358

XT. S. 202; Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31; Taylor v. Louisiana,

370 U. S. 154; Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961);

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 IX 2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960).

A State law construed to authorize discrimination by privately

owned restaurants was thought to be “clearly violative of the

Fourteenth Amendment” by Mr. Justice Stewart, concurring in

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 TJ. S. 715, 727.

Three dissenting Justices agreed this would follow if that were a

proper construction of the law, 365 XT. S. 715, 727, 729. State laws

requiring segregation in the use and occupancy of privately owned

property were invalidated in Buchanan v. Warley, 245 TJ. S. 60,

and Harmon v. Tyler, 273 XT. S. 668.

Among the numerous cases forbidding segregation in publicly

owned but privately leased facilities, see Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 XJ. S. 715; Turner v. Memphis, 369 TJ. S.

350; Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n, 347 XJ. S. 971, vacat

ing and remanding, 202 F. 2d 275; Derrington v. Plummer, 240

F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956), cert. den. sub nom. Casey v. Plummer,

353 TJ. S. 924.

14

of state power in all forms.” Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S.

at 20. See also Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U. S. 715, 722.

In the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17, this Court held

outside the Amendment’s scope individual action “unsup

ported by State authority in the shape of laws, customs, or

judicial or executive proceedings” or “not sanctioned in

some way the State,” 109 U. S. at 17. The opinion re

ferred to “State action of every kind” inconsistent with

equal protection of the laws, id. at 1 1 ; to “the operation of

State laws, and the action of State officers executive or

judicial,” id. at 11. Repeatedly, the opinion held within the

scope of the Fourteenth Amendment “State laws or State

proceedings,” id. at 11; “some State action,” id. at 13; “acts

done under State authority,” id. at 13; “State action of

some kind,” id. at 13; and the opinion pointed out that

States are forbidden to legislate or act in a particular

way,” id. at 15. The Fourteenth Amendment is “addressed

to counteract and afford relief against State regulations or

proceedings,” id. at 23.

Racial discriminations “are by their very nature odious

to a free people whose institutions are founded upon the

doctrine of equality.” Hirabayashi v. United States, 320

U. S. 81, 100. Certainly in this case the State is more

deeply implicated in enforcing that racism so odious to our

Constitution than it was m Shelley v. Kraemer. For here

the State has not merely held its courts open to suitors who

would seek their aid in enforcing discrimination, but has

taken an active initiative in prosecuting petitioners crimi

nally and sentencing them to prison terms.

Moreover, petitioners here assert not merely the general

ized constitutional right found in the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to be free from racial dis-

15

crimination. 42 U. S. C. 1981 provides: “ ‘All persons

within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the

same right in every State and Territory to make and en

force contracts, * * # and to the full and equal benefit of all

laws and proceedings for the security of persons and prop

erty as is enjoyed by white citizens * * * . ” ’ 42 U. S. C. 1982

provides: “ ‘All citizens of the United States shall have

the same right, in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed

by white citizens thereof to * * * purchase * * * real and

personal property.’ ” Referring to similar statutory provi

sions involving jury service, this Court has declared: “ ‘For

us the majestic generalities of the Fourteenth Amendment

are thus reduced to a concrete statutory command when

cases involve race or color which is wanting in every other

case of alleged discrimination.’” Fay v. New York, 332

U. S. 261, 282-283.

The opinion below stresses that Kress’s is “a privately

owned corporation” and “in the conduct of its store in

Durham is acting in a purely private capacity” (R. 77).

But “private” is a word of several possible meanings. To

the extent that concepts of privacy play a part in defining

rights here at issue, Kress’s privacy should be seen as it

really is. Any suggestion that some exception to the Shelley

rule should be made for a corporation which has sought

state aid in enforcing racial discrimination in its enterprise

open to the general public for profit, because somehow the

inviolability of a private home may be impaired, is with

out merit. This prosecution is not asserted to be in aid of

any'interest in privacy of the property owner, for it has

opened the store to the public in general. Moreover, the

proprietor has not expressed its preference, rather it has

sought state aid to enforce the custom of the community.

Were a state to enforce a trespass law to protect a real

interest in some private aspect of property a different

16

result might be required because of the importance of the

right of privacy which finds firm support in the decisions

of this Court. Examples where such countervailing con

siderations have applied are cases such as Breard v. Alex

andria, 341 U. S. 622, 626, 644, and Kovacs v. Cooper, 336

U. S. 77. On the other hand a case such as Martin v.

Struthers, 319 IT. S. 141, is an instance where even con

siderations of privacy did not overcome a competing con

stitutional right like freedom of religion.2 In this case the

right to freedom from state imposed racial discrimination

does not compete with any interests the state may have in

protecting privacy.3

2 And see Watchtower Bible and Tract Soc. v. Metropolitan Life

Ins. Co., 297 N. Y. 339, 79 N. E. 2d 433 (1948), in which the New

York courts distinguished between the right to solicit in the streets

of a large scale housing project and to go, without invitation, into

the hallways to visit private apartments.

3 To weigh considerations of privacy in a case involving racial

discrimination would comport with the views of the framers of

the Fourteenth Amendment. During the debate on the bill to

amend the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27, which served as the

precursor to the Civil Rights Act of 1875, 18 Stat. 335, Senator

Sumner distinguished between a man’s home and places and facili

ties of public accommodation licensed by law: “Each person,

whether Senator or citizen, is always free to choose who shall be his

friend, his associate, his guest. And does not the ancient proverb

declare that a man is known by the company he keeps? But this

assumes that he may choose for himself. His house is his ‘castle’;

and this very designation, borrowed from the common law, shows

his absolute independence within its walls; * * * but when he leaves

his ‘castle’ and goes abroad, this independence is at an end. He

walks the streets; but he is subject to the prevailing law of Equal- 'v

ity,- nor can he appropriate the sidewalk to his own exclusive use,

driving into the gutter all whose skin is less white than his own!

But nobody pretends that Equality in the highway, whether on

pavement or sidewalk, is a question of society. And, permit me to

say that Equality in all institutions created or regulated by law is

as little a question of society.” (Emphasis added). After quoting

Holingshed, Story, Kent, and Parsons on the common law duties

of innkeepers a,nd common carriers to treat all alike, Sumner then

said: “As the inn cannot close its doors, or the public conveyance

refuse a seat to any paying traveler, decent in condition, so must it

17

B. Certainly, at Least, the State May Not by Its Police

and Courts Enforce Such Segregation When It Stems

From a Community Custom of Segregation Which

Has Been Generated by State Law.

Certainly, at the very least, the well established rule—

that states may not enforce racial discrimination—dis

cussed in part I, applies where the racial segregation is

not a matter of private choice, but expresses deep-rooted

public policy.

That segregation was a “custom of the community” (E.

22) is stated expressly in the record, although one hardly

need turn there to learn a fact concerning conditions in

society so well known. Child Labor Tax Case, 259 U. S. 20,

27 (Chief Justice Taft). Kress’s manager, however, made

clear that the store’s segregation policy was merely that of

the community.

It is the policy of our store to wait on customers de

pendent upon the customs of the community. . . .W e

have a stand-up counter on the first floor, and we serve

Negroes and whites at that stand-up counter. We also

serve white people who are accompanied by Negroes

at the stand-up counter. . . . Even if Negroes aecom-

be with the theater and other places of public amusement. Here are

institutions whose peculiar object is the ‘pursuit of happiness,’

which has been placed among the equal rights of all.” Cone. Globe

42d Cong., 2d Sess. 382-383 (1872).

It is not unreasonable that considerations of privacy should

weigh so heavily. The right of privacy against intrusion on one’s

premises or into one’s personal affairs, 4 Blaekstone’s Commentaries

Ch. 13, §5 (6) (Wendell’s ed. 1850), was recognized at common law,

and is recognized generally in American law’. See A. L. I., Restate

ment of Torts, §867 (1939). This Court has recently reiterated that

the due process clause protects privacy against intrusion by the

States. Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643, 654, 655; Wolf v. Colorado,

338 U. S. 25, 27-28. Cf. Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U. S. 325, 336

(Justice Brandeis dissenting); Public Utilities Comm’n v. Pollalt

343 U. S. 451, 464, 468.

18

panied by white people were orderly at our luncheon

ette because of the policy of the community we would

not serve them, and that was our policy prior to May

16, 1960. . . . It is not the custom of the community

to serve Negroes in the basement luncheonette, and

that is why we put up the signs, “Invited Guests and

Employees Only” (E. 22-23).

The Civil Rights Cases speak of “customs having the

force of law,” 109 U. S. 3, 16, as a form of state action.4

Here, as in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, “segregation

is basic to the structure of . . . [the state] as a community;

the custom that maintains it is at least powerful as any

law.” (Mr. Justice Douglas concurring, at 181).6

But this custom of North Carolina is not separate from

law. It has roots in and tills interstices of a complex net

work of state mandated segregation. The North Carolina

Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on

Civil Eights has concluded that “so long as these compul

sory statutes are on the books, some private citizens are

more than likely to take it upon themselves to try to en

force segregation.” 6

Most of this law was enacted about the turn of the

twentieth century.7 These state and city imposed require-

4 See also 109 U. S. at 21: “long custom, which had the force of

law. . . ”

5 This Court has recognized that “ ‘Deeply embedded traditional

ways of carrying out state policy . . . ’—or not carying it out—‘are

often tougher and truer law than the dead words of the written

tex t. Nashville C. & St. L. R. Co. v. Browning, 310 U S 362 369 ”

Poe v. Tillman, 367 U. S. 497, 502. ’

. 6 A discussion and presentation of this legislation may be found

in North Carolina Advisory Committee to the United States Com

mission on Civil Rights, Statutes and Ordinances Requiring Segre

gation by Race (March 9, 1962) (mimeographed) (hereafter

cited as North Carolina Advisory Committee).

7 North Carolina Advisory Committee 23.

19

ments govern not only activities furnished by the state but

privately-owned facilities as well. The subordinate role to

which the segregation laws relegate Negroes is well illus

trated by the national guard statute, N. C. Gen. Stat. §127-6:

“No organization of Colored Troops shall be permitted

where White troops are available, and while permitted to

be organized, colored troops shall be under command of

white officers.”

W7hile the state has repealed statutes requiring segrega

tion in the public schools, school segregation continues to

be enforced by other means.8 Mental institutions,9 orphan

ages,10 and schools for the blind and deaf,11 must be segre

gated as must prisons,12 and training schools.13

Separate tax books must be kept for white, Negro, Indian

and corporate taxpayers.14

State law requires racial distinctions where municipali

ties take possession of existing cemeteries.16 Some city

8 Under the North Carolina Pupil Assignment Law “without a

single exception, the boards have made initial assignment of white

pupils to previously white schools and Negro children to previously

Negro schools.” United States Commission on Civil Rights, The

Fifty States Report 477 (1961).

9 G. S. 122-3-6.

10 G. S. 116-138 to -142.

11 G. S. 116-109, -120, -124.

12 G. S. 148-43.

13 G. S. 134-79 to -84; G. S. 134-84.1 to -84.9. On the various forms

of segregation in health care, among patients as well as professional

personnel, in public as well as private facilities, see Equal Protec

tion of the Laws Concerning Medical Care in North Carolina, Sub

committee on Medical Care of the North Carolina Advisory Com

mittee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights (undated)

(mimeographed).

14 G. S. 105-323.

15 G. S. 65-37.

20

ordinances designate particular cemeteries for colored per

sons and specific burial grounds for white citizens ;16 others

note simply that places of interment are to be marked for

Negroes or for Caucasians.17 Separate funeral homes must

be maintained throughout the state.18

Municipalities also have enacted legislation requiring

segregation. For example, a Charlotte ordinance, Article I,

Section 5, Charlotte City Code, delineates the metes and

bounds of the area within which its Negro police have au

thority. See North Carolina Advisory Committee to the

United States Commission on Civil Eights, op. cit. supra,

at 3. The Director of the Department of Conservation and

Development, while not requiring segregation in state

parks, discourages Negroes from enjoying white facilities.

Id. at 8.

North Carolina has also undertaken extensively to regu

late so-called “private” relationships. There remains on

the books of North Carolina (although invalid in view of

decisions of this Court, Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373;

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903) a statute requiring racial

segregation in passenger trains and steam boats. G. S. GO-

94 to -97. The Utilities Commission is directed by G. S.

62-44 and G. S. 62-127.71 to require separate waiting rooms.

Street cars must by statute be boarded white from the

front and colored from the rear. G. S. 60-135 to -137. The

Corporation Commission has been upheld in requiring en

forced segregation on motor buses. Corporation Comm’n

v. Transportation Committee, 198 N. C. 317, 320, 151 S. E.

648, 649 (1930). In that opinion Judge Clarkson emphasized

16 Charlotte City Code, eh. 7, sec. 7-9, 7-56; Sec. 7-19 of the Lum-

berton Code; Sec. 8-1, Burlington Code.

17 Sec. 6-42, Winston-Salem Code; Sec. 7-9, Charlotte City Code.

18 G. S. 90-212.

21

that separation or segregation “has long been the settled

policy” of North Carolina. See G. S. 60-139; State v. John

son, 229 N. C. 701, 51 S. E. 2d 186 (1949).

Persons engaged in businesses employing more than two

males and females must segregate on the basis of race in

toilet facilities. G. S. 95-48. See G. S. 72-46 (1941). Per

sons operating restaurants and other food handling estab

lishments are required to obtain a permit from the State

Board of Health. G. S. 72-46. The State Board inspector’s

official form contains as one of the criteria on which res

taurants are graded the factor of whether toilet facilities

are “adequate for each sex and race.” North Carolina Ad

visory Committee Report 18.

Fraternal orders may not be authorized to do business in

North Carolina if white and colored persons are members

of the same lodge. G. S. 58-267.

Marriage is forbidden between persons of the Negro and

white races by the Constitution of North Carolina, Art.

XIV, §8 (1868); G. S. 14-181 and G. S. 51-3.

Various statutes and ordinances throughout North Caro

lina require segregation in taxicabs, carnivals, other places

of amusement, and restaurants. North Carolina Advisory

Committee Report 15, 17-20. Among these ordinances is

one of the City of Durham requiring that in public eating

places where persons of the white and colored races are

permitted to be served, there shall be private, separate

rooms for the accommodation of each race. Id. at 18.19

19 The state did not rely on the ordinance at trial, nor was it

adverted to on appeal. Heretofore, the North Carolina Supreme

Court has declined to notice municipal ordinances not introduced

into evidence at trial. See State v. Clyburn, 247 N. C. 455, 101

S.E. 2d 295 (1958).

22

C. Vann Woodward has written of the relative recency

of the segregation system in America:

Southerners and other Americans of middle age or

even older are contemporaries of Jim Crow. They

grew up along with the system. Unable to remember

a time when segregation was not the general rule

and practice, they have naturally assumed that things

have ‘always been that way.’ Or if not always, then

‘since slavery times,’ or ‘since The War,’ or ‘since

Reconstruction.’ Some even think of the system as

existing along with slavery. Few have any idea of the

relative recency of the Jim Crow laws, or any clear

notion of how, when, and why the system arose. Wood

ward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, vii-viii (1955).

Even after the end of Reconstruction and during the

so-called period of “Redemption” beginning around 1877,

the rigid segregation system characteristic of later years

had not become the rule. The history of segregation makes

clear that during* the early years after Reconstruction

Negroes were unsegregated in many public eating estab

lishments in the South. Id. at 18-24. The Jim Crow or

segregation system became all-pervasive some years later

as a part of the aggressive racism of the 189Q’s and early

1900’s, including Jim Crow laws passed at that time, which

continued until an all-embracing segregation system had

become the rule. In this way law shaped custom. Id. at

ch. II.

Professor Woodward writes:

At any rate, the findings of the present investigation

tend to bear out the testimony of Negroes from various

parts of the South, as reported by the Swedish writer

G-unnar Myrdal, to the effect that ‘the Jim Crow stat

utes were effective means of tightening and freezing—

23

in many cases instigating—segregation and discrimina

tion.’ The evidence has indicated that under conditions

prevailing in the earlier part of the period reviewed

the Negro could and did do many things in the South

that in the latter part of the period, under different

conditions, he was prevented from doing. Id. at 90-91.

# # # # #

It has also been seen that their [Negroes] presence

on trains upon equal terms with white men was once

regarded as normal, acceptable, and unobjectionable.

Whether railways qualify as folkways or stateways,

black man and white man once rode them together and

without a partition between them. Later on the state-

ways apparently changed the folkways—or at any rate

the railways—for the partitions and Jim Crow cars

became universal. And the new seating arrangement

came to seem as normal, unchangeable, and inevitable

as the old ways. And so it was with the soda fountains,

eating places, bars, waiting rooms, street cars, and

circuses. Id. at 91-92.

Thus the system of segregation in places of public ac

commodations, has from the beginning been a product of

government, politics, and law.

This Court has recognized how law may work its effect

in ways other than requiring obedience to statutory text.

In Pollock v. Williams, 322 U. S. 4, the Court discharged

the petitioner on a writ of habeas corpus because a statu

tory presumption had induced a plea of guilty:

The State contends that we must exclude the prima

facie evidence provision from consideration because

in fact it played no part in producing this conviction.

Id. at 13.

# # * # *

We cannot doubt that the presumption provision had

a coercive effect in producing the plea of guilty. Id.

at 15.

And see—Engel v. Vitale, 370 U. S. 421, 431 (indirect co

ercive pressure upon religious minorities). As was said in

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 463, “The crucial

factor is the interplay of governmental and private action,

for it is only after the initial exertion of state power . . .

that private action takes hold.” 20

Therefore it hardly can be urged that the management

was acting privately, unsanctioned by the state. Apart from

state support of management’s decision to segregate, that

decision itself represented the policy of North Carolina

induced and nourished by its laws. As Mr. Justice Douglas

wrote in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 181, the pro

prietor’s “preference does not make the action ‘private,’

rather than ‘state,’ action. If it did, a minuscule of private

prejudice would convert state into private action. More

over, where the segregation policy is the policy of a state,

it matters not that the agency to enforce it is a private

enterprise.”

C. A F o r t io r i , the State May Not Arrest and Convict P eti

tioners for H aving Violated a Segregation Rule

W hich Stem s From a State Generated, Com m unity

Custom o f Segregation in Prem ises in W hich the

State Is D eeply Involved T hrough Its L icensing and

R egulatory Powers,

The nature of the State’s involvement—demonstrated by

extensive regulation and licensing—in the premises where

20 This Court has struck down state action which would enable

private individuals to seek reprisals against persons opposed to

racial discrimination, N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449. A

fortiori, the link between state requirements of segregation and the

conduct it fosters—not merely permits—should be recognized.

25

petitioners were arrested for violating the state-generated

community custom shows even further the invalidity of the

judgment below. This discrimination has been enforced in

an area of public life with which the State is so intimately

involved that Kress’s lunch counter business is by law

required to be extensively licensed and regulated. The

very publicness of the enterprise is demonstrated not only

by the fact that Kress serves the general public, but by

the interest which the State has demonstrated in that ser

vice. In addition to the detailed regulation of business cor

porations (including foreign corporations)21 North Carolina

law requires various licenses,22 imposes taxes,23 and author

izes state and local health regulation24 of this type of

business. As Mr. Justice Douglas wrote in Garner v. Louisi

ana, 368 U. S. at 183-84:

A state may not require segregation o f. the races on

conventional public utilities any more than it can seg

regate them in ordinary public facilities. As stated by

the court in Boman v Birmingham Transit Co. (CA

5 Ala) 280 F2d 531, 535, a public utility “is doing some-

21 North Carolina General Statutes, §55-140.

22 A state license is required for the operation of a soda fountain

G. S. §55-79 or a chain store G. S. §105-98. A license is required for

all establishments selling prepared food G. S. §105-62. Separate

licenses are required to sell other items, such as tobacco products,

G. S. §105-85 or records and radios, G. S. §105-82.

23 Retail stores must collect sales and use taxes for the state to

keep their licenses to do business (G. S. §105-164.4-6).

^ State law establishes an overlapping pattern of health regula

tions for restaurants. See N. C. Gen. Laws, Ch. 130 (1957). Section

13 of this chapter authorizes each county to operate a health de

partment ; local boards of health can make rules and regulations

“not inconsistent with state law,” Sec. 17(b). Both the State Board

of Health and the Durham County Board of Health prescribe rules

applicable to food service establishments. See State Board of

Health Laws, Rules and Regulations; County of Durham Sanitary

Code, Sec. 1.

26

thing the state deems useful for the public necessity or

convenience.” It was this idea that the first Mr. Justice

Harlan, dissenting in Plessy v Ferguson, . . . ad

vanced. Though a common carrier is private enter

prise, “its work” he maintained is public. Id., at 554.

And there can be no difference, in my view, between one

kind of business that is regulated in the public interest

and another kind so far as the problem of racial seg

regation is concerned. I do not believe that a State

that licenses a business can license it to serve only

whites or only blacks or only yellows or only browns.

Race is an impermissible classification when it comes

to parks or other municipal facilities by reason of the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

In Public Utilities Comm’n v. Poliak, 343 U. S. 451,

this Court found sufficient governmental responsibility to

require decision of a Fifth Amendment due process claim

where the principal governmental involvement was a deci

sion by a regulatory body to do nothing about private

activity (radio broadcast on streetcars) it could have pro

hibited. The lunch counter in this case is also regulated

by government, although perhaps not so closely as the

streetcar company in Poliak. But this case has an element

that the Poliak case did not, i.e., that government has done

so much to encourage racial segregation in public life that

it must share responsibility for the discriminatory rule.

And see Steele v. Louisville and Nashville R.R. Co., 323

U. S. 192; Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73; Betts v. Easley,

161 Kan. 459, 169 P. 2d 831. In each of these cases, state

initiative and licensing in establishing and maintaining the

enterprise led to a holding or implication that the Fifth

or Fourteenth Amendments forbid racial discrimination.

27

Here, indeed, is a case where the State “to some sig

nificant extent” in many meaningful “manifestations has

been found to have become involved. . . . ” Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 IT. S. 715, 722.

D. No Essential Property of S. H. Kress and Co. Is H ere

at Issue; the Right to Make Racial Distinctions at a

Single Counter in a Store Open to the Public Does

Not Outweigh the High Purposes of the Fourteenth

Am endm ent.

The highest court of North Carolina has attempted to

differentiate this case from others which have refused to

sanction state enforcement of racial discrimination by as

serting that it was merely neutrally enforcing a “funda

mental, natural, inherent and inalienable” (R. 81) private

property right, allegedly “ ‘a sacred right, the protection of

which is one of the most important objects of government’ ”

(R. 81). Referring to the claimed right to exclude peti

tioners the court below held, “white people also have

constitutional rights as well as Negroes, which must be

protected, if our constitutional form of government is not

to vanish from the face of the earth” (R. 84).

This description of the property right cannot withstand

analysis. First, the court below dealt with the alleged right

of the property owner to racially discriminate as if it were

inviolate, when actually, states can prohibit racial discrim

ination in public eating places without offending any con

stitutionally protected property rights.25 And though the

laws violate the Fourteenth Amendment, North Carolina

has hardly hesitated in imposing the requirement of racial

•25 See Western Turf Ass’n v. Greenberg, 204 TJ. S. 359; Bailway

Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88; District of Columbia v. John R.

Thompson Co., 346 U. S. 100; Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan,

333 U. S. 28; Konvitz & Leslies, A Century of Civil Rights 172-177

(1961).

28

segregation on private property owners.26 Thus, of course,

the asserted property right to treat the races as one desires

on his property is very far indeed from an absolute or an

inalienable right and has not even been so regarded by

North Carolina. “ [T]he power of the State to create and

enforce property interests must be exercised within the

boundaries defined by the Fourteenth Amendment.” Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22, citing Marsh v. Alabama, 326

U. S. 501. Indeed, the Court said in Marsh v. Alabama,

supra, at 506, that constitutional control becomes greater

as property is more public in its use:

The more an owner for his advantage, opens up his

property for use by the public in general, the more do

his rights become circumscribed by the statutory and

constitutional rights of those who use it. Cf. Eepublic

Aviation Corp. v. Labor Board, 324 IT. S. 793, 798, 802,

n. 8.

Of course, the Fourteenth Amendment does not forbid a

state to assist in the enforcement of property rights as

such. Indeed, for an obvious example, the state has an

obligation not to engage in or assist in the invasion of the

privacy of the home. Considerations of privacy, discussed

in more detail, supra, pp. 15-16, offer one useful basis

for distinguishing between permissible and impermissible

types of state action.