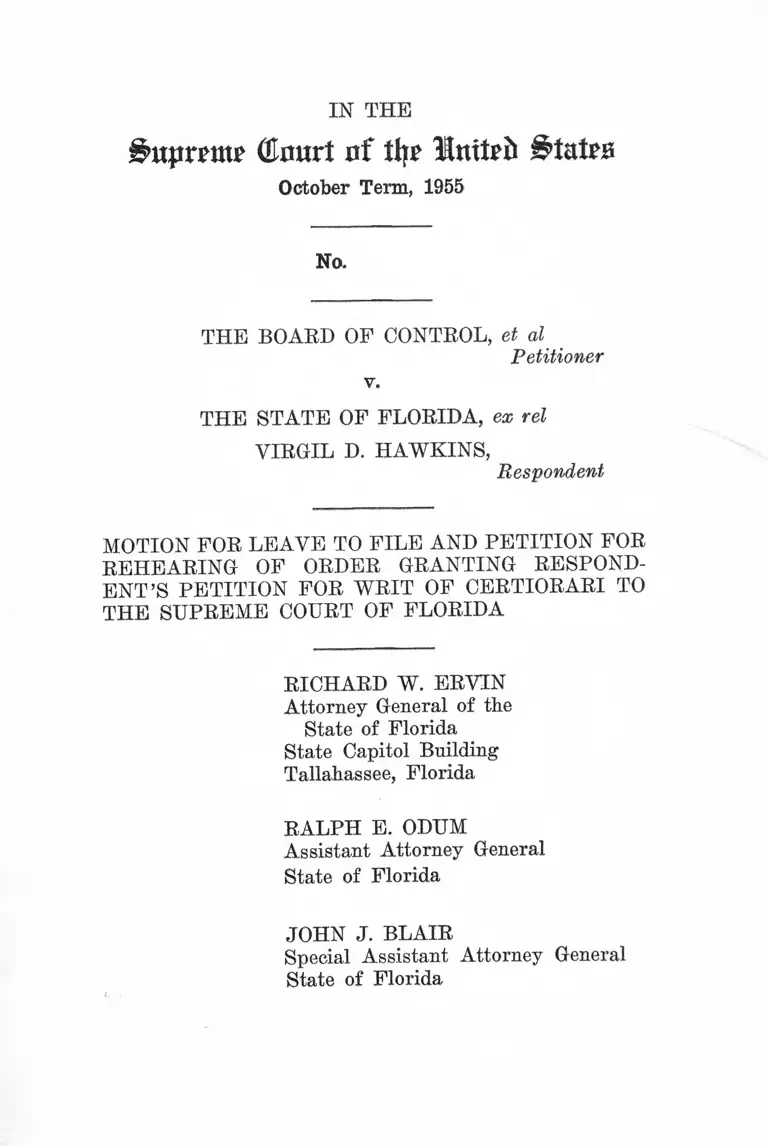

Board of Control v. Florida Motion for Leave to File and Petition for Rehearing of Order Granting Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 2, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Control v. Florida Motion for Leave to File and Petition for Rehearing of Order Granting Writ of Certiorari, 1956. a2506730-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c90c1f92-75d9-4ebd-b18d-c2ee9a71a011/board-of-control-v-florida-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-petition-for-rehearing-of-order-granting-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

iatpmtu' (Emirt of tho States

October Term, 1955

No.

THE BOARD OF CONTROL, et al

Petitioner

v.

THE STATE OF FLORIDA, ez rel

VIRGIL D. HAWKINS,

Respondent

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND PETITION FOR

REHEARING OF ORDER GRANTING RESPOND

EN T’S PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

RICHARD W. ERVIN

Attorney General of the

State of Florida

State Capitol Building

Tallahassee, Florida

RALPH E. ODUM

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

JOHN J. BLAIR

Special Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

IN THE

&uprmp Court of thr llmtvb States

October Term, 1955

No.

T he B oard op Control, et al

Petitioner

v.

T he S tate op F lorida, ex rel V irgil D . H a w k in s ,

Respondent

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE PETITION

FOR REHEARING

The Attorney General of the State of Florida respect

fully moves for leave to file the annexed petition for re

hearing of the order of this Court denying respondent’s

petition for certiorari and granting respondent’s petition

for writ of certiorari with an order for respondent’s prompt

admission to the College of Law at the University of Flor

ida, such order bearing the date of March 12, 1956.

Rehearing is sought at this time because, as is pointed

out more fully in the annexed petition, the Court was

not properly apprized of the reasoning involved in the

cases cited in support of its order or of the import of

said cases, nor has the Court been informed as to the

grave problems of public interest involved in the admis

sion of negro students to the University of Florida College

of Law at this time and the serious consequences affecting

the administration and operation of Florida’s institutions

of higher learning as a result of the order of the Court.

IN THE

f>uprm? (tart of thr Initefc States

October Term, 1955

No.

T he B oaed op C ontrol, et al

Petitioner

v.

T he S tate of F lorida, exrel V irgil D. H aw k in s ,

Respondent

PETITION FOE REHEARING OF ORDER GRANTING

RESPONDENT’S PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTI

ORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

The Attorney General of the State of Florida prays

that this Court grant rehearing of its order of March 12,

1956, which denied respondent’s petition for certiorari

hut granted respondent’s petition for writ of certiorari

and required prompt admission of respondent to the

College of Law of the University of Florida. The At

torney General further requests that this Court make its

order recognizing authority in the Florida Supreme Court

to allow the petitioner, the Board of Control of the State

of Florida, the same latitude in dealing with the grave

problems presented the State of Florida, on the college grad

uate school level as is permitted on the elementary and

secondary school levels, under the Court’s second or imple

mentation decision of May 31, 1955, in Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483, 98 L, Ed. 873, 74 S. Ct.

686.

2

Reasons for Rehearing and Order Permitting Ex

ercise of Judicial Discretion and Reasonable Time for

Compliance.

First This Court in denying to the highest appellate

court of the State of Florida the judicial authority to con

sider and apply equitable principles in cases involving the

admission of negro students to graduate professional

schools, regardless of local conditions, the public welfare,

or any other untoward or aggravating circumstance, has

departed from judicial principles long established and rec

ognized by this Court. This is particularly true in this

instance when the Court forbids, at the very threshold of

the consideration of the problems, the receiving and con

sideration of evidence which may be pertinent to the ex

istence of problems of administration, public safety, and

welfare which traditionally and historically are consid

ered by a court of equity. We respectfully submit that

equity is a concept of justice which has always been rec

ognized by this Court and which has been in existence

longer than the United States Supreme Court itself; that

it is a fundamental and inherent right in the American

system of jurisprudence which should not be abrogated

by a decision of this Court, that it is a right which can only

be exercised or denied in accord with the specific facts in

volved in each particular case and cannot be abridged as

a general rule of law or conclusion of fact prior to a con

sideration of pertinent evidence as to the facts or the

granting of an opportunity to present such evidence when

it is sought. Since the original decision of this Court in

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483,

entered May 17, 1954, the State of Florida has followed a

sound and stable course in dealing with problems arising

in the public schools and universities of Florida as a result

of said decision.

3

In considering the petition of respondent in this case

for admission to the University of Florida Law School, the

Florida Supreme Court felt it necessary to a proper con

sideration of the issue to adopt equitable principles in the

application of the decree of this Court. The Florida court

took into consideration factors known to it at the time,

and exercising its judicial discretion, ruled that a reason

able time should be allowed for the taking of testimony

to disclose facts which might indicate serious problems

which would result if an order of immediate admission

was entered. A court of equity is never active against

conscience or public convenience. Bowman v. Wathen, 1

How. 189, 11 L. Ed. 97. This Court has always felt it

proper to apply equitable principles against the enforce

ment of legal doctrines when it was disclosed that public

interest might be affected adversely by the enforcement of

a legal decree. Courts of equity may appropriately with

hold their aid when the plaintiff is using the right asserted

in a manner contrary to the public interest. Morton Salt

Co. v. Suppiger Co., 314 U. S. 488, 62 S. Ct. 402, 86 L. Ed.

363.

The Supreme Court of Florida followed these long ad

hered to principles in order to avoid the emotional furor

and disorder which commonly result in the agitation of

racial antagonists, as has been demonstrated recently at

the University of Alabama in a case involving the abrupt

admission of a negro student. The extent to which a court

of equity may grant or withhold its aid and the manner

of molding its remedies may be affected by the public in

terest involved. U. S. v. Morgan, 307 U. S. 183, 59 S. Ct.

795, 83 L, Ed. 1211.

The State of Florida has been more successful than any

other southern state in maintaining an emotional equilib

4

rium during its attempts to solve the dilemma created by

this Court’s ruling that segregation in public schools can

not be required by law. This is attributable to the fact

that the Florida Supreme Court and school officials have

consistently followed long established equitable principles

in dealing with this problem. Traditionally, equity has been

characterized by practical flexibility in shaping its rem

edies and by the facility for adjusting and recognizing

public and private needs. Brown v. Board of Education

of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L, Ed. 1083. It

is the duty of a court of equity to strike a proper balance

between the needs of the plaintiff and the consequence of

giving the desired relief. Eccles v. Peoples Bank, 333 U. S.

426, 68 S. Ct. 641, 92 L. Ed. 784.

Their established forms being flexible, courts of equity

may adapt proceedings and remedies to the circumstances

of cases and may formulate them to safeguard, adjust and

enforce the rights of all parties. Alexander v. Hillman, 296

U. S. 222, 56 S. Ct. 204, 80 L, Ed. 192.

The Florida Supreme Court in this case has determined

that the need for equity is as urgent on the college grad

uate level as on the elementary and secondary school lev

els. Having so decided, the Florida court requested that

information be obtained as to the factual circumstances

involved at the University of Florida to assist it in making

a decision as to whether or not Hawkins could be admitted

forthwith without a serious disruption of the University,

or whether there was a genuine need for the application

of equitable principles in coping with the problems in

volved. The Florida Supreme Court properly concluded

that since equity jurisdiction was part and parcel in the

implementation of the U. S. Supreme Court’s segregation

decision, it should not be denied application to afford com

5

plete relief as the justice and equity of the instant case

might require. Hepburn v. Dunlop, 1 Wheat 179, 4 L. Ed.

65. A court of equity which has jurisdiction of a question

may proceed to its final and complete decision. Stephens

v. M ’Cargo, 9 Wheat 502, 6 L. Ed. 145. The whole contro

versy will be settled by a court of equity where it has jur

isdiction of a part involving the problems upon which the

whole depends. Massie v. Watts, 6 Crunch 148, 3 L. Ed.

181. This Court has consistently permitted time in imple

mentation of decrees involving long established public pol

icy and affecting public interest. Recognizing the need for

adjustment, the Court has granted time in dissolution of

corporations in anti-trust cases. United States v. American

Tobacco Co., 221 U. S. 106, 31 S. Ct. 632, 55 L. Ed. 663;

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U. S. 1, 31 S. Ct.

502, 55 L. Ed. 619. In the area, of nuisance litigation, this

Court has recognized the need for a period of gradual tran

sition. New Jersey v. New York, 283 U. S. 473, 51 S. Ct.

519, 75 L. Ed. 1176; Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 206

U. S. 230, 27 S. Ct. 618, 51 L. Ed. 1038; People of the State

of New York v. State of New Jersey and Passaic Valley

Sewerage Commissioners, 256 U. S. 296, 41 S. Ct. 492, 65

L. Ed. 937.

Second This Court in this case has in effect denied the

application of equitable principles on the assumption that

no problems exist which would justify the ameliorating in

fluence of equity in seeking compliance. This Court in its

order makes the statement that “ . . . there is no reason for

delay.” This statement appears to be the sole basis and

justification for the Court’s order. The statement is in

error and candidly is ipse dixit unsupported by any evi

dence before the Court in this or any other case under its

jurisdiction. This Court has reached a premature legal

conclusion as to matters of fact, since no facts have been

6

considered by this Court and the Court has denied the

petitioner an opportunity to present evidence pertaining to

and substantiating such facts, and more to be deplored,

has abruptly denied the Florida Supreme Court the right

to proceed with its orderly review of the case in a thor

ough, careful manner in the light of equity principles

essential to the public interest involved.

Third The prior decisions cited by this Court in sup

port of its order are irrelevant to the sole issue involved

in the present case at this time, to wit: Do factual prob

lems exist which must be considered by courts of first

instance in making proper determinations of pertinent ques

tions relating to the feasibility or practicability of now

allowing admission of a negro student and others similarly

situated to graduate schools of the University of Florida!

As a predicate for its decree, the Court cited its ruling

in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. 8. 629; Sipuel v. Board of

Regents of the University of Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631; and

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Educa

tion, 339 U. S. 637. These cases, however, were decided

under the “ separate but equal doctrine.” In all of these

cases the question presented to the Court and decided by

the Court was whether or not petitioner had a legal right

to enter the university in question because of unequal fa

cilities or benefits. That question is not involved in this

case. This case involves a situation where segregation per

se has been held unconstitutional and now presents the

question whether equitable principles will be applied in

balancing Hawkins’ individual rights, and those of others

similarly situated, against the public interest and welfare.

The question relating to the application of equitable prin

ciples in permitting a reasonable time for delay by a lower

court was not advanced or considered in the earlier cases

7

which this Court cited in its order.

In other words, in the earlier cases cited, the Court was

concerned with the question of the petitioner’s right to

admission because of unequal facilities or benefits. In this

case, the Court is now concerned only with the question as

to when respondent and those similarly situated should be

admitted.

Fourth Petitioner is prepared to submit competent and

conclusive evidence, if permitted by the Court, to show

that valid, sufficient and urgent reasons do exist in Florida

for delay in admitting negroes to the graduate professional

schools; that if such evidence is ignored the public safety

in Florida will be endangered and the administration and

operation of institutions of higher learning in Florida will

be disrupted. Pursuant to an order of the Florida Supreme

Court in this case, a commissioner of the court was desig

nated to take testimony as to the factual conditions at

the University of Florida which might be pertinent to the

problems here considered. A survey of the University of

Florida Law College and of the state university system as

a whole was undertaken by the State Board of Control in

order to comply with the Florida Supreme Court’s order.

Although this survey is now in the process of being made

and has not been completed, certain preliminary informa

tion has already been obtained which is at variance with

the statement of this Court in its order to the effect that

“ there are no reasons for delay.” For example, the sur

vey demonstrates an acute shortage of physical facilities

available for students already enrolled at the University

of Florida and at all state universities. It demonstrates an

annual growth of student enrollment which is so larg’e

that the present multi - million dollar construction pro

gram now in progress on all of the university campuses

8

may be insufficient to meet the minimum requirements of

students even in the absence of an abrupt shift in college

populations resulting from integration. These factors are

further complicated by the attitudes of state university

students and their parents. For example, all students now

enrolled at the University of Florida were requested to

fill out a questionnaire designed to ascertain as accurately

as possible the future actions of students in the event that

integration takes place immediately at the University. 21.04

per cent of the questionnaires returned stated that the

students would not be willing to admit negroes to the Uni

versity of Florida under any circumstances. 14.01 per cent

stated that they wanted to delay admission of negroes to

the white universities as long as legally possible, and 41.45

per cent stated that they thought negroes should not be

admitted until after a reasonable period of preparation for

integration. Only 22.39 per cent indicated that they were

willing to admit negroes to the white universities imme

diately.

Questionnaires were mailed to all students at the Uni

versity of Florida and 75.31 per cent of the students re

turned their questionnaires, so it is felt that this is a rep

resentative expression of student body opinion and rea

sonably accurate in attempting to predict or foresee prob

able future actions of the student body.

Questionnaires were also sent to the parents of all stu

dents now enrolled at the University of Florida and 46.8

per cent have been returned at this time. Only 9.04 per

cent of the parents indicated a willingness to accept negro

students at the white universities immediately. 24.10 per

cent stated that they believed that integration should not

take place until after a reasonable period of preparation.

23.98 per cent stated that they thought that integration

9

should be delayed as long as legally possible. 41.62 per

cent, which is by far the largest group, stated that inte

gration should not take place under any circumstances. A

factor which is of even more significance in administrative

planning for the university is the indication that large

numbers of parents would cause their sons or daughters

to leave the university if integration takes place at this

time. 32.29 per cent of the parents indicated that they

would transfer their sons or daughters to another institu

tion which does not admit negroes if integration is required

at the University of Florida at this time.

It is submitted that these facts indicate a strong prob

ability of a serious disruption at the University of Florida

if respondent is admitted at this time. Although the sur

vey has not as yet been completed, it is being made as

rapidly as possible and the information which it will dis

close will be available to the courts by the May 31, 1956

deadline set by the Florida Supreme Court. This study

which is being made will in no way affect the time of

Hawkins' admission to the University of Florida (since un

der the regulations of the University applicable to all stu

dents, he could not enter until next September), unless of

course, the information obtained reveals that such serious

problems of readjustment do actually exist as to require

the courts in the public interest to permit still further

delay. A major problem of readjustment to an inte

grated university system, which is now being diligently

studied and solutions sought as rapidly as possible, has to

do with the effect of an order of immediate integration in

the University of Florida upon the Florida university for

negroes (Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University).

As we have demonstrated to the Court in our amicus curiae

brief filed in the Brown case, there is a significant gap in

10

achievement levels between white and colored students in

Florida, Only five per cent of the negro high school stu

dents are in the upper 50 percentile of the white students.

This factor, from a realistic standpoint, requires, lower ad

mission standards at the State University for negroes than

those in existence at the white universities. This has been

recognized and accepted under a segregated public school

system which has prevailed in Florida up until this time

as a necessary expedient in dealing with the problem

of trying to provide the best possible college education for

both races. If, however, the state universities are inte

grated at either the graduate or undergraduate level at

this time, it will of course entail a revision of this policy

and the State Board of Control will be forced to place all

state universities on the same basis from the standpoint

of admission requirements. Such an abrupt change could

only result in the elimination of at least 90 per cent of

negro students who wish to attend a state supported in

stitution of higher learning in Florida,

It is submitted that an abrupt change of this kind would

be inequitable and grossly unfair to the negro population

in Florida, and that rather than an abrupt, drastic change

in admission requirements forced by the Court at Florida

Agricultural and Mechanical University at this time, it

would be more equitable and in the public interest to per

mit the negro university to continue to improve its stand

ards in an orderly and realistic manner. We submit that

it would be grossly unfair to deprive 90 per cent of the

negroes in Florida of the opportunity for an education in

a state university simply to compel the admission of one

individual into the University of Florida.

Fifth, It is respectfully submitted that factual condi

tions in Florida cannot be accurately measured by the

11

experience of other states in admitting negroes to white

universities. As has been recognized by this Court in the

Brown case, there are significant regional differences and

variations throughout the south on the problem of inte

gration and these local conditions should be given con

sideration. Although integration has taken place at the

college graduate level in some state universities without

creating serious problems of administration, it is equally

true that the attempt to force an immediate integration

at the University of Alabama did create serious problems.

It would be unrealistic and dangerous to assume in ad

vance as the Court has done in its order of March 12, 1956,

in this case, that Florida will fall in either category. There

are many significant and real differences between Florida,

Oklahoma and Alabama or any other state in which this

problem has previously been considered by the Court. These

distinctions involve the social structure, the economics and

attitudes of the people in the several states and cannot in

good conscience be ignored. They must not be ignored by

this court if the public interest is to be considered, simply

on the assumption that “ there are no reasons for delay.”

Recent events indicating a sharp deterioration in racial

relations in Florida would preclude the serious considera

tion of this assumption. This deterioration has reached

such serious proportions that it has been officially noted

by the chief executive of the state, who felt it necessary

to call a conference of state, governmental and educational

leaders on March 21 of this year for the purpose of dis

cussing and seeking a solution to what appears to be a

problem involving the peace and safety of the people of

Florida. Such diverse leaders of national prominence as

the President of the United States and Nobel prize win

ning author William Faulkner, on separate occasions when

12

discussing the problems encountered in effectuating inte

gration, have stressed the need for moderation.

It is respectfully submitted and with all due deference,

that this Court did not act in a moderate manner when it

abruptly vacated its order of May 24, 1954, and thereby

interrupted the calm, careful, moderate and equitable ap

proach of the Florida Supreme Court in its study of this

problem. Previous pronouncements have all indicated that

it is the policy of this Court to permit time and allow liti

gants to be heard when a decision of the Court involved

long established policy. This was permitted in each in

stance in order to avoid hardship or injury to public or

private interests. The present decision requires even more

consideration of the problem of time and adjustment than

in the earlier cases. This is clearly true because it involves

a vast problem of human engineering, as contrasted to pre

vious delays for adjustment granted in anti-trust cases,

nuisance cases and similar cases where economic problems

of great magnitude confronted the Court. Many of these

cases were cited to the Court and discussed by the petitioner

in our amicus curiae brief in the Brown case.

Sixth The factual matters which petitioners seek to

bring before the Court are of such grave importance to

the public safety and welfare of the people of Florida and

to the institutions of higher learning in Florida that the

Honorable LeBoy Collins, Governor of the State, as its

chief executive and spokesman for the people, has requested

that we hereby transmit his request for permission to ap

pear with the Attorney General of Florida before this Court

in this appeal in order to avert, if possible, a disruption

in public affairs of statewide and even national importance.

Accordingly, we do hereby respectfully request that the

Honorable LeBoy Collins be permitted to appear and be

13

heard orally along with the Attorney General of Florida

in behalf of this petition for re-consideration.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, it is respectfully urged

that rehearing be granted and that, upon such rehearing,

the application of equitable principles be permitted in put

ting into effect this Court’s decree of integration in the

Florida University College of Law.

Respectfully submitted,

R ichard W . E rvin

Attorney General

State of Florida

R alph E . Odu m

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

J o h n J . B lair

Special Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL

I hereby certify that the foregoing petition for rehearing

is presented in good faith and not for unnecessary delay

and is restricted to grounds specified in Rule 58 of the

rules of this Court.

R a l p h E . Odum

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

14

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that copies hereof have been fur

nished to Horace E. Hill, Esq., 610 Second Avenue, Day

tona Beach, Florida, and to Robert L. Carter, Esq., 20

West 40th Street, New York, Attorneys for Respondent,

by Registered Mail, the 2nd day of April, 1956.

R alph E. O dum

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

APPENDIX

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 624.— October Term, 1955.

T h e S tate of F lobida, ex rel.

V ibgil D. H a w k in s ,

Petitioner

v.

T h e B oard of C ontrol, et al.

On Petition for Writ

of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of

Florida.

(March 12, 1956.)

Per Curiam.

The petition for certiorari is denied.

On May 24, 1954, we issued a mandate in this case to

the Supreme Court of Florida. 347 U. S. 971. We directed

that the case be reconsidered in light of our decision in

the Segregation Cases decided May 17, 1954, Brown v.

15

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483. In doing so, we did

not imply that decrees involving graduate study present

the problems of pxiblic elementary and secondary schools.

We had theretofore, in three cases, ordered the admission

o f Negro applicants to graduate schools without discrimi

nation because of color. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629;

Sipuel V: Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma,

332 U. S. 631; cf. McLaurm v. Oklahoma State Regents for

Higher Education, 339 U. S. 637. Thus, our second deci

sion in the Brown case, 349 U. S. 294, which implemented

the earlier one, had no application to a case involving a

Negro applying for admission to a state law school. Ac

cordingly, the mandate of May 24, 1954, is recalled and

is vacated. In lieu thereof, the following order is entered:

Per Curiam: The petition for writ of certiorari is

granted. The judgment is vacated and the case is remanded

on the authority of the Segregation Cases decided May 17,

1954, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483. As this

case involves the admission of a Negro to a graduate pro

fessional school, there is no reason for delay. He is en

titled to prompt admission under the rules and regulations

applicable to other qualified candidates. Sweatt v. Painter,

339 IT. S. 629; Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University

of Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631; cf. McLaurm v. Oklahoma State

Regents for Higher Education, 339 U. S. 637.

I