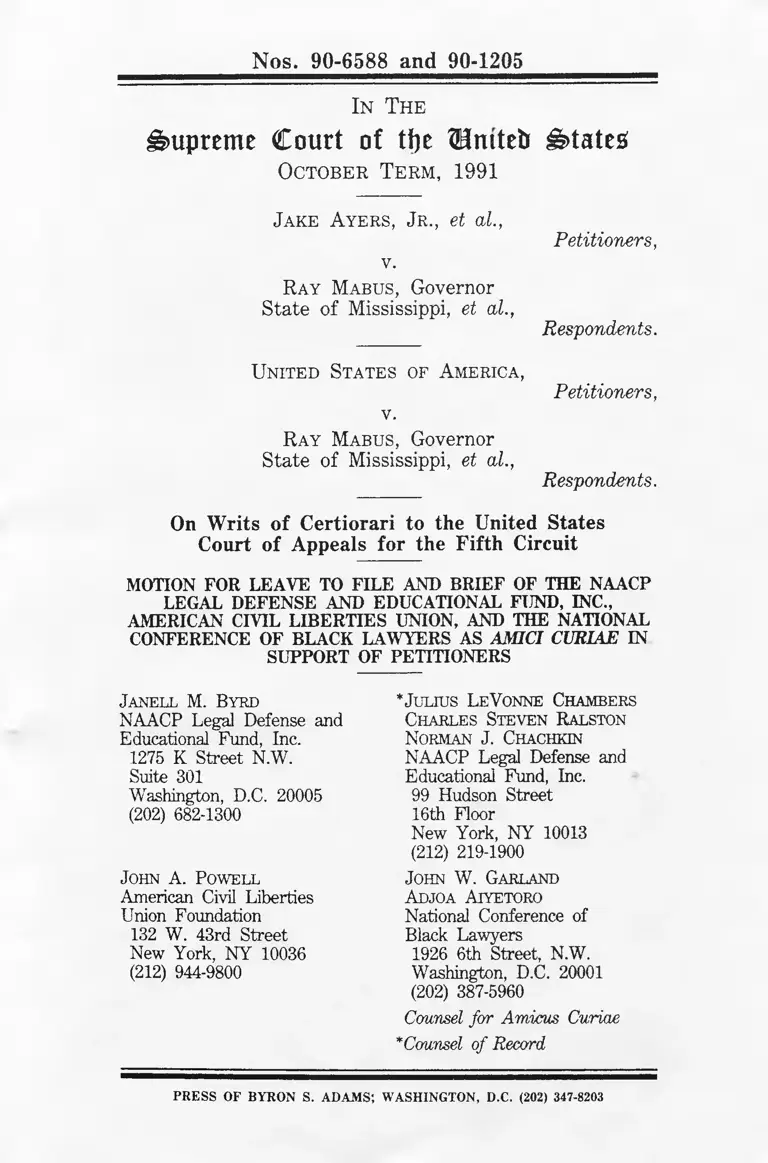

Ayers v. Mabus Motion for Leave to File and Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., American Civil Liberties Union, and the National Conference of Black Lawyers as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ayers v. Mabus Motion for Leave to File and Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., American Civil Liberties Union, and the National Conference of Black Lawyers as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners, 1991. 22183e85-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c9315c0d-eb14-42f7-91dd-e878abef9eb6/ayers-v-mabus-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-inc-american-civil-liberties-union-and-the-national-conference-of-black-lawyers-as-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

N os. 90-6588 and 90-1205

In Th e

Supreme Court of tfje Umtetr States;

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1991

J ake A y e r s , J r ., et al.,

v.

R ay Mabu s, Governor

State of Mississippi, et al.,

U n ited States of A m erica ,

v.

R ay Mabu s, Governor

State of Mississippi, et al.,

Petitioners,

Respondents.

Petitioners,

Respondents.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND BRIEF OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND THE NATIONAL

CONFERENCE OF BLACK LAWYERS AS AMICI CURIAE IN

SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

John A. Powell

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 W. 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

* Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Steven Ralston

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

John W. Garland

A djoa Aiyetoro

National Conference of

Black Lawyers

1926 6th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

(202) 387-5960

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

*Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS; WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

Nos. 90-6588 and 90-1205

In the

S u p re m e C o u r t o f tfje ® m te b S t a t e s

October Term, 1991

Jake Ayers, Jr., et a l ,

Petitioners,

v.

Ray Mabus, Governor

State of Mississippi, et a l ,

Respondents.

United States of America,

Petitioners,

vs.

Ray Mabus, Governor,

State of Mississippi, et al.

Respondents.

MOTION OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AND THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK

LAWYERS FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AS AMICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational, Fund, Inc.

(LDF), the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and the

2

National Conference for Black Lawyers (NCBL) respectfully

move the Court for leave to file the attached brief as amici

curiae in support of petitioners. Both the Ayers petitioners

and the United States have consented to the filing of this

brief. Respondents, Ray Mabus, Governor of the State of

Mississippi, et al. , have not responded to request for consent.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

is a non-profit corporation established to assist African

American citizens in securing their constitutional and civil

rights. LDF has had a major role in litigation efforts

challenging discrimination and segregation in education.1

LDF successfully litigated the first court challenge to racial

segregation in Mississippi’s higher education system, Meredith

v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 371 U.S. 828

1See, e.g., Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). LDF

represented the plaintiffs in litigation that resulted in the initiation of

desegregation efforts in public higher education systems in 18 states,

including the State of Mississippi. Adams v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp. 92

(D.D.C.), modified and a ff’d unanimously en banc, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C.

Cir. 1973), dismissed sub. nom. Women’s Equity Action League v.

Cavazos, 906 F.2d 742 (D.C. Cir. 1990). Other LDF higher education

desegregation cases include: Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950);

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950); Adams v.

Lucy, 228 F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1955), cert, denied, 351 U.S. 931 (1956).

3

(1962). The questions presented here involve the

interpretation of five cases litigated by LDF .2

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a non

profit, non-partisan organization with nearly 300,000

members dedicated to principles of liberty and equality

embodied in the Constitution. As part of its commitment to

legal equality, the ACLU has long opposed any forms of state

imposed racial discrimination.3 This case raises fundamental

questions about the constitutionality of state imposed

segregation in higher education. Its proper resolution,

therefore, is a matter of direct concern to the ACLU.

The National Conference of Black Lawyers (NCBL),

founded in 1968, is an organization comprised of

approximately 2,500 black lawyers and legal workers, many

2Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986); Green v. County School

Board o f New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Geier v. Alexander, 801

F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1986); Norris v. State Council o f Higher Education

fo r Virginia, 327 F. Supp. 1368 (E.D. Va.), qff’d mem., 404 U.S. 907

(1971); Alabama State Teachers Association v. Alabama Public School and

College Authority, 289 F. Supp. 784 (M.D. Ala. 1968), ajf’dper curiam,

393 U.S. 400 (1969).

3ACLU currently represents respondents in Brown v. Board o f

Education, 892 F.2d 851 (10th Cir. 1989), petition fo r cert, filed, 58

U.S.L.W. 3725 (U.S. April 26, 1990) (No. 89-1681), and Pitts v.

Freeman, 887 F.2d 1438 (11th Cir. 1989), cert, granted, 111 S. Ct. 949

(Feb. 19, 1991) (No. 89-1290).

4

of whom are graduates of historically black colleges.

NCBL’s membership is engaged in legal and legislative

efforts to increase educational opportunities and advancements

for black and other minority persons. Several NCBL lawyers

filed the original complaint in this case.

Given amici’s substantial experience in school

desegregation litigation, it is submitted that the brief will be

of assistance to the Court. Amici, therefore request that the

motion be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

John A. Powell

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 W. 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

/si Janell M. Bvrd_______

* Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

John W. Garland

Adjoa Aiyetoro

National Conference of

Black Lawyers

1926 6th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

(202) 387-5960

Counsel fo r Amicus Curiae

* Counsel o f Record

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of Amici ............................................................... 1

Statement of the Case...................................................................1

Introduction ........................................................................ 1

Statement of Relevant Facts ............................................. 5

I. The Establishment and Maintenance of Mississippi’s

Racially Dual System from the Mid-1800’s to 1962 5

II. The Separate and Unequal System of Higher Education

Remains Substantially Intact: 1962-1987 15

Summary of the Argument ............................................. 25

A rg u m e n t.............................................................................. 27

I. Mississippi’s Duty Under 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i) To

"Take Affirmative Action To Overcome The Effects Of

Prior Discrimination" Is Not Satisfied By Abandoning

Expressly Discriminatory Policies Where Mississippi’s

Prior Discrimination Continues to Have Effect. . . 27

A. Petitioners’ Regulatory Claim Is Properly

Considered Prior to the Constitutional Claim . . 27

B. 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6) (i) Has The Force Of

Law................................................................................. 28

C. Where Continuing Discriminatory Effects of the De

Jure System Exist, 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i) Mandates

Implementation of Affirmative Measures To Overcome

Those Effects................................................................ 30

1. The Plain Language of §. 100.3 (b)(6) (i) . . . 30

2. The History of § 100.3(b)(6) ( i ) ......................... 31

i

3. The Illustrative Example .................................. 32

4. HEW Criteria Interpreting § 100.3(b)(6)(i) . 32

D .The En Banc Majority Erred In Concluding that

Bazemore v. Friday Precludes Liability Under 34

C .F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i). 34

II. The Fourteenth Amendment Imposes Upon Mississippi

An Affirmative Duty to Eliminate the Vestiges of Its

Racially Dual Higher Educational System "Root and

Branch." . . . . . . . . . . . . .................................... 41

A. A Fundamental Tenet of the Court’s Equal

Protection Jurisprudence Is the Affirmative Duty

to Eliminate the Vestiges of a Discriminatory

System. ...................................................................... 42

B. The Affirmative Duty To Eliminate The Vestiges

Of A Formerly De Jure System Is Appropiately

and Necessarily Applied In the Higher Education

Context If the Harm to Petitioners Is to Cease. . 46

C. Mississippi Has Failed to Eliminate the Dual

System "Root and Branch." ..................................... 51

1. Mississippi Must Eliminate Continuing Intentional

Discrimination. ....................................................... 51

2. The State Must Eliminate Vestiges of the Dual

System Which Continue to Impede Equal Educational

Opportunity. .......................................................... 55

D . The En Banc Majority Erred In Concluding That

Mississippi Need Not Take Additional Steps To

Dismantle Its Racially Dual Structure Because To

Do So Would Preclude Diversity Among

Institutions and Student Choice................................. 57

ii

1. The Diversity and Choice Ultimately Protected By

the Majority Decision Are Based Upon the Stigma of

Racial Inferiority Precluded By Brown.............. 57

2. The Majority Erred In Concluding That Any Remedy

Would Destroy the System By Precluding Diversity

of Institutions........................................................... 60

Conclusion 65

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Adams v. Califano, 430 F. Supp. 118

(D.D.C. 1977). ....................................................... 63

Adams v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp.

92 (D.D.C. 1973), a ff’d, 480

F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir, 1973 .................................. 17

Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d at

1165 (D.C. Cir. 1973)............... ... 17, 63

Alabama State Teachers Association v.

Alabama Public School and College

Authority (ASTA), 289 F. Supp. 784

(M.D. Ala. 1968) a ff’d per curiam,

393 U.S. 400 (1969) .............................................. 47

Albem arle v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) . . . . . . . ................................................ 28

Alexander v. Holmes County Board o f

Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969)....................... 16

Arvizu v. Waco Independent School

D ist., 495 F.2d 499 (5th Cir.

1974).................. 63

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley

Authority, 297 U.S. 288 (1936)....................... 2-8

Batterton v. Francis, 432 U.S. 416

( 1 9 7 7 ) ............ 29

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385

(1986).......................................... 26, 34, 35, 36, 39, 40

IV

CASES PAGE

Bazemore v. Friday, 751 F.2d 662

(4th Cir. 1984), a ff’d in pan,

rev’d in pan , 478 U.S. 385

(1986)........................................................................ 35, 36

Board o f Education o f Oklahoma City

v. Dowell, 111 S. Ct. 630

(1991)........................................................................ 43, 55

Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954)....................................10, 12, 48 62

Brown v. Board o f Education,

349 U.S. 294 (1955).......................................... 42

Carter v. Jury Committee o f Greene

County, 396 U.S. 320 (1970).............................. 44

Chrysler Corp. v. Brown,

441 U.S. 281 (1979)............................................. 29

Coffey v. State Education Finance

Committee, 296 F. Supp. 1389

(S.D. Miss. 1969)................................................ 17

Columbus Board o f Education v.

Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979)........................... 55

Dayton Board o f Education v.

' Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979)........................ 55

Donald v. Tubb, No. 3583 (S.D.

Miss. June 10, 1964)............... 16

Ford Motor Co. v. United States,

405 U.S. 562 (1 9 7 2 ) .......................................... 45

v

CASES PAGE

Gaston County v. United States,

395 U.S. 285 (1969) .............................................. 44

Geier v. Alexander,

801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1986) . ......................... 46

Geier v. Dunn, 337 F. Supp. 573

(M.D. Tenn. 1972) .............................................. 46

Geier v. University o f Tenn.,

597 F.2d 1056 (6th Cir.), cert.

deniedx 444 U.S. 886 (1979) ............................... 46

Green v. New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) . .................................... 26, 51, 54

Griffin v. County School Board o f

Prince Edward County, 377

U.S. 218 (1964)................................................... 44

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222

(1985) . ................................................................ 26, 51, 54

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

Denver, 413 U.S. 189 (1973)........................... 43

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

Denver, 521 F.2d 465 ........................ ... 63

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974)..................... 33

Lee v. Macon County Board o f Education,

448 F.2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971)........................... 63

Lee v. Macon County Board o f Education,

267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala.),

a ff’d sub. nom. Wallace v. United

States, 389 U.S. 215 ( 1 9 6 7 ) .............................. 47

vx

CASES PAGE

Local 93, International Association o f

Firefighters v. Cleveland,

478 U.S. 501 (1986).......................................... 33

Louisiana v. United States,

380 U.S. 145 (1965)............................................. 43

McDowell v. Tubb, No. 3425

(S.D. Miss. June 4, 1963)................................. 15

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents,

339 U.S. 637 (1950).......................................... 48

McPherson v. School District No. 186,

426 F. Supp. 173 (S.D. 111. 1976).................. 63

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 342

(5th Cir. 1962), cert, denied,

371 U.S. 828 (1962).......................................... 14

Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson,

A l l U.S. 57 (1 9 8 6 ) ............................................. 33

Milliken v. Bradley,

433 U.S. 267 (1977)............................................. 43

Mississippi University fo r Women v.

Hogan, 458 U.S. 718 ( 1 9 8 2 ) ........................... 24

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U.S. 337 (1938).......................................... 48

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980).................. 28

Mt. Healthy Board o f Education v. Doyle,

429 U.S. 274 (1977)..................... ' ................... 54, 63

vii

CASES PAGE

New York City Transit Authority v.

Beazer, 440 U.S. 568 (1979).............................. 28

Norris v. State Council o f Higher

Education fo r Virginia, 327 F, Supp.

1368 (E.D. Va. 1971), a ff’dm em .,

404 U.S. 907 (1971)............................................. 47

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455

(1973) ...................................................................... 17

Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F. Supp. 937

(M.D. Tenn. 1968) . ........................................... 47

Sipuel v. University o f Oklahoma,

332 U.S. 631 (1948)............................................. 48

Skidmore v. Swift, 323 U.S. 134

(1944)..................................................................... 33

Standard Oil Co. v. United States,

221 U.S. 1 (1 9 1 1 ) ............................................. 44, 45

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

o f Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971)........................ 43, 44

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629

(1950)..................................................................... 48

United States v. Alabama, 628 F. Supp

1137 (N.D. Ala. 1985), rev’d on

other grounds, 828 F.2d 1532

(11th Cir.), cert, denied, 487

U.S. 1210 (1987)......................................... 48

United States v. Barnett,

330 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1963)........................... 14, 15

CASES PAGE

United States v. Barnett, 376 U.S. 681

(1964).......................................... .. ........................ 14, 15

United States v. Board o f Education o f

Waterbury, 560 F.2d 1103

(2d Cir. 1977)...................................................... 63

United States v. Columbus Municipal

Separate School District, 558 F.2d 228

(5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S.

1013 (1978)......................................... 24

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co.,

323 U.S. 173 (1944)............... 45

United States v. Hinds County School

Board, 417 F.2d 852 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied, 396 U.S. 1032 (1970),

delaying order rev’d sub. nom.

Alexander v. Holmes County Board

o f Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969)........................... 16

United States v. Lawrence County

School District, 799 F.2d

1031 (5th Cir. 1986).......................................... 24

United States v. Louisiana, 692

F. Supp. 642 (E.D. La.

1988, vacated, 751 F. Supp.

606 (E.D. La. 1 9 9 0 ) .................................... 39, 47, 49

United States v. Mississippi,

567 F.2d 1276 (5th Cir. 1978)........................... 24

United States v. Natchez Special

Mun. Separate School D ist.,

No. 1120 (W) (S.D. Miss.

Jul. 24, 1989)...................................................... 24

IX

CASES PAGE

United States v. Pittman,

808 F .2d 385 (5th Cir. 1987) . . . . . . . . . . 24

United States v. Scotland Neck

City Board o f Education,

407 U.S. 484 (1972) .................................... .. . 55

United States v. United States

Gypsum Co., 340 U.S. 76

(1950) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

United States v. Wells Fargo

Bank, 485 U.S. 351 (1988) . ............................ 28

Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative

Extension Serv., 372 F.

Supp. 126 (N.D. Miss. 1974),

a ff’d in relevant part,

528 F.2d 508 (5th Cir. 1976)........................... 19

Williams v. Mississippi,

170 U.S. 213 (1898).......................................... 7

Wright v. Council o f City o f

Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972)........................ . 55

STATUTES, CONSTITUTIONS, AND

REGULATIONS

42 U.S.C. §2000d .................................................... 29, 31

20 U.S.C. §1001-1146a ................................................ 48

Smith-Lever Act of 1914, Ch. 79,

38 Stat. 372 ............. .. ............................................ 8

x

STATUTES, CONSTITUTIONS, AND

REGULATIONS PAGE

1862 Morrill Land Grand Act,

Ch. 314, 24 Stat. 440 ............................................. 6

34 C.F.R. §100.3(b)

(6) ( i ) ..................... 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 40

34 C.F.R. §100.5 (h ) ..................... ........................ 25, 32, 40

43 Fed. Reg. 6658 ........................ . .32 , 33, 39, 61, 62, 64

38 Fed. Reg. 17,979 ......................................................... 31

38 Fed. Reg. 17,920 ..................... ................................. 29

29 Fed. Reg. 16,299 .....................

51 Cong. Record 3 ........................ ................................. 8, 9

Miss. Const, art. VIII,

§213-B (1954) ........................

Miss. Const, of 1890,

art. 2, §207 ..............................

Act of April 5, 1956,

1956 Miss. Laws 337 . . . . .............................. 12

Act of April 5, 1956,

1956 Miss. Laws 303 . . . . .............................. 12

Resolution of Interposition,

1956 Miss. Laws 741 . . . .

Act of Feb. 24, 1956,

1956 Miss. Laws 366 . . . . ............ .. ............... 12

Act of April 4, 1955,

1955 Ex. Sess. 133

xi

12

STATUTES, CONSTITUTIONS, AND

REGULATIONS PAGE

1944 Miss. Laws Ch. 159 .............................................. 10

1940 Miss. Laws 352 ....................................................... 10

1878 Miss. Laws, Ch. XIV,

§35 . . . . . . . . ......................................................... 6

Revised Code of Mississippi

(1857) Ch. 33, §10,

art. 51 ........................................................................... 5

Mississippi Code of 1798-1848

(A. Hutchinson, 1848)

Ch. 9, art. 37 . .................................................... 6

Ch. 9, art. 45 . . . . . ........................................ 6

Ch. 37, art. 3, § 2 ................................................ 5

GOVERNMENT REPORTS

Bureau of Census, U.S. Dept.

of Commerce (1987).......................................... 49

Bureau of Education, United

States Dept, of the Interior,

Survey o f Negro Colleges &

Universities ( 1 9 2 9 ) ............................................. 9

Dept, of Labor, Occupational

Quarterly Outlook (1990)................................. 49

Dept, of Labor, Dept, of Educ.,

Dept, of Commerce, Building

a Quality Workforce (1988).............................. 49

xii

GOVERNMENT REPORTS PAGE

Population o f the United States

in 1860 .................................................................. 7

Seventh Census o f the United

States (1 8 5 3 ) ............................................ 7

Sixth Census or Enumeration o f

the Inhabitants o f the

United States (1841)............................................. 7

State Superintendent of Education,

Twenty Years o f Progress,

1910-1930 and a Biennial

Survey Scholastic Years

1929-30 and 1930-31 o f Public

Education in Mississippi (1 9 3 1 ) ..................... 8, 9

State Superintendent of Public

Education, Biennial Report

and Recommendations to the

Legislature o f Mississippi

fo r the Scholastic Years

1937-38 and 1938-39

(1939)............................................................................ 10

BOOKS

Branch, Parting the Waters America in

the King Years 1954-63 (1988)........................ 15

DuBois, Black Reconstruction in

America (1935)............................................................ 6

Foner, Reconstruction, America’s

Unfinished Resolution: 1863

-1877 (1 9 8 8 ) ............................................................... 6

xiii

BOOKS PAGE

Kirwan, Revolt o f the Rednecks

(1951) ...................................................................... 7

Kluger, Simple Justice (1976) .................................. 58

McMillen, Dark Journey (1989) . . ......................... 10

Trueheart, The Consequences o f

Federal and State Resource

Allocation and Development

Policies fo r Traditionally

Black Land-Grant Institu

tions: 1862-1954 (1979).................................... 6, 9

Woodward, Origins o f the New

South: 1877-1919 ( 1 9 5 1 ) ................................. 7

Woodward, The Strange Career

o f Jim Crow (3d revised

ed. 1974) . . . . . . . . ....................................... 15

xiv

Interest of Amici

Amici NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., American Civil Liberties Union, and National

Conference of Black Lawyers1 have extensive experience in

desegregation litigation and share a committment to the goal

of equal educational opportunity. Amici believe that their

views will be of assistance to the Court.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Introduction

In broad terms, this case presents the question whether

the State of Mississippi has taken sufficient steps to satisfy its

statutory and constitutional duties to dismantle the racially

dual and discriminatory system of higher education that it

created and maintained for more than a century. In

determining whether the dual system or its vestiges continue

to have discriminatory effects, the history of the development,

scope and duration of Mississippi’s dual educational system

is the necessary backdrop. The details of that history,

therefore, are provided in the factual statement below.

‘Each organization is described fully in the preceding Motion for

Leave to File and incorporated by reference herein.

2

In amici's view, race always has played an enormous role

in shaping educational opportunities, and thus, life’s

opportunities, for the people of the State of Mississippi. In

the 1870’s Mississippi moved from enforced ignorance

imposed upon its black population to a system of rigid

segregation of blacks in grossly inferior educational systems.

It is undisputed that this practice of rigid segregation and

inequality continued unbreached at every educational level

from the 1870’s until at least 1962.

Pressured to abandon its discriminatory system, state

officials engaged in "massive resistance" leading to

widespread violence. Creative strategies instituted during the

period of massive resistance and thereafter, as well as the

continued existence of a dual structure itself, have

successfully maintained Mississippi’s segregated and

profoundly unjust system of higher education, under which

educational opportunities for the vast majority of black

Mississippians are severely limited.

Today, 70% of Mississippi’s black students are

automatically excluded from its five historically white

institutions (HWIs) of higher education by virtue of an

3

admissions test score requirement whose existence is

indisputably rooted in intentional discrimination. Thus the

vast majority of black students attending in-state public

colleges are effectively limited to choosing among three

historically black institutions (HBIs), which without apology

Mississippi funds at a significantly lower rate than the three

HWIs where 86% of its white college students are educated.

Mississippi at most has made meager efforts to change its

dual system, as is evidenced by the limited success it has had.

In 1974, in response to a notice from-federal authorities that

the state’s higher education system remained racially dual and

was in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

Mississippi submitted a "Plan of Compliance." However, the

federal government found the plan inadequate. Mississippi

proceeded to implement its inadequate plan, but refused to

fully fund it.

More evident, in fact, than any attempts to dismantle the

dual system, are Mississippi’s efforts to maintain the dual

system through the use of policies that are euphemistically

labelled "race-neutral" only because their express racial

characteristics have been eliminated. Those policies seize

4

upon the institutional and personal cumulative deficits bom of

the inequity of past discrimination as the very justification for

perpetuating racial disparities.

Much more than "race-neutral" policies - the thinly

disguised tools of the massive resistance movement — is

required to eliminate "root and branch," the deep traces of a

discriminatory system that has been so firmly implanted as

Mississippi’s. Nonetheless, a divided en banc Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that Mississippi can

abandon even its meager efforts and need do no more. Amici

urge the Court to reverse that decision and require affirmative

measures to eliminate the vestiges of the dual system in order

to provide black citizens of Mississippi full and equal rights

to educational opportunities provided by the state.

5

STATEMENT OF RELEVANT FACTS2

I. The Establishment and Maintenance o f Mississippi’s

Racially Dual System from the Mid-1800’s to 1962

In 1823, Mississippi imposed a criminal prohibition on

gatherings of blacks (free and slave) for the purpose of

learning to read or write.3 Most blacks, of course, were still

enslaved in 1844 when the state established the University of

Mississippi.4 The school began operating in 1848, and in

1854 expanded to include a law school.5 The legislature

2We adopt the detailed factual review provided by the Ayers

petitioners. The following abbreviations are used herein: United States’

Petition Appendix ("PA"), Ayers Petitioners’ Petition Appendix ("PPA"),

United States’ exhibits ("USX"), defendants’ exhibits ("BDX”), Ayers

plaintiffs’ exhibits ("PX"), stipulations of the parties ("S."), and the trial

transcript ("Tr."). The Joint Appendix was not completed in time to allow

citation by amici.

3The statute provided an exception for attendance at religious services

conducted by a white minister or attended by two "respectable" white

persons appointed for that purpose and established a penalty of corporeal

punishment up to 39 lashes for violations. Ch. 37, art. 3, § 2, Mississippi

Code o f 1798 - 1848 (A. Hutchinson, 1848); Ch. 33, § 10, art. 51,

Revised Code o f Mississippi (1857)(re-enactment).

‘‘The current names of the institutions are used in this section, except

where otherwise indicated.

3The University of Mississippi opened its School of Medicine in 1903

(PA 110a).

6

mandated that the school serve whites only. (PA 109a-

110a .)6

In 1871, Mississippi’s Reconstruction Legislature7 opened

Alcorn State University for blacks. In 1878, with the entry

of the Redeemer Legislature,8 the school was designated as

the state’s land-grant college for blacks pursuant to the 1862

Morrill Land Grant Act, Ch. 314, 24 Stat. 440. (PA 110a-

111a.)9 That same year, the state established Mississippi

State University and designated it as the land-grant college for

whites (PA 111a).10 • Thereafter, the state established the

6In 1846, Mississippi set up a system of common schools. Ch. 9,

art. 37, Mississippi Code o f 1798-1848. See also, ch. 9, art. 45 1)

Mississippi Code o f 1798'-1848 (common schools for "free white youth").

f e e generally W.E.B. DuBois, Black Reconstruction in America 431-

51 (1935); E. Foner, Reconstruction, America’s Unfinished Revolution:

1863-1877 (1988).

*ld.

“The Redeemer Legislature also enacted a statute requiring racial

segregation in the schools. 1878 Miss. Laws, ch. XIV, § 35. The

requirement of racially separate schools was made part of Mississippi’s

Constitution in 1890. Miss. Const, of 1890, art. 2, § 207.

‘“State funding for Alcorn University has consistently been lower than

that for Mississippi State. W.E. Trueheart, The Consequences o f Federal

and State Resource Allocation and Development Policies fo r Traditionally

Black Land-Grants Institutions: 1862-1954 32-33 (University Microfilms

International, Ann Arbor, Michigan) (1979). See also Brief of Alcorn

State University National Alumni Association as Amicus Curiae in Support

of Petitioners at 4-5.

7

Mississippi University for Women for whites in 1884, the

University of Southern Mississippi for whites in 1910, and

Delta State University for whites in 1924 (PA 11 la-114a).

During this period of rapid expansion of educational

opportunities for Mississippi’s white population, persons of

African descent comprised the majority of Mississippi’s

population.11 The state, however, restricted educational

opportunities for Mississippi’s black majority.12 As

Mississippi’s United States Senator in 1914, James K.

Vardaman, a former Governor who at one point served as ex

officio president of Alcorn, successfully argued against a

"Blacks were a majority of the population in Mississippi from at least

1840 until 1940, when whites first showed a slim majority. Sixth Census

or Enumeration o f the Inhabitants o f the United States 250, 252 (1841);

Seventh Census o f the United States: 1850 447 (1853); Population o f the

United States in 1860 264, 266 (1864); PX 200 at 351 [census data].

12These restrictions developed out of a fear that blacks would once

again seek to exercise the vote -- blacks were disenfranchised by 1890

under the Mississippi Plan, see Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U.S. 213

(1898)(upholding exclusionary measures); C. Vann Woodward, Origins o f

the New South: 1877-1919 321-350 (1951) — the belief that the limited

funding available for education should be spent on whites -- see A.

Kirwan, Revolt o f the Rednecks 145 (1951) -- and a desire to protect and

maintain the dominant position of the white race — id. at 145-46

(Mississippi’s Governor James K. Vardaman argued that money spent for

Negro education was a "positive unkindness" because it "simply renders

[the Negro] unfit for the work which the white man has prescribed, and

which he will be forced to perform." "The negro (sic) . . . will not be

permitted to rise above the station which he now fills.").

8

provision in the Smith-Lever Act of 1914, Ch. 79, 38 Stat.

372, that would have guaranteed equal funding for black land-

grant colleges. Vardaman argued that the funding for blacks

should be limited and controlled by whites:

[T]he negro (sic) has never enjoyed any civilization

except that which has been inculcated by the white

man, and that civilization has lasted only so long as

he was under the control and domination of the white

man. When left absolutely to himself he has

universally retrograded to the barbarism of the

jungles.

51 Cong. Record 3, at 2652 (1914); see also id. at 2931.13

At the elementary and secondary level, the Mississippi

State Superintendent of Education reported that for school

year 1930-31, 98.3% of the total enrollment for black

children was in the first eight grades, with 64% in grades

one to three.14 A summary of the values of school plants for

1929-30 shows $40,000,000 for white schools and $3,052,300

for blacks.15 Of the total expenditures for elementary and

13With the discretion given to the states by Congress to allocate the

Smith-Lever Act funds, Mississippi did as Vardaman promised — allocated

all the funds to its white land-grant college. USX-695t.

14State Superintendent of Education, Twenty Years o f Progress, 1910-

1930 and a Biennial Survey Scholastic Years 1929-30 and 1930-31 o f

Public Education in Mississippi 24 (1931).

15Id. at 203.

9

secondary school for 1929-30, 69.5% went to instructional

services — 60.2% for whites and 9.3% for blacks.16

In higher education, Alcorn, the only public college for

blacks until 1940, functioned largely as an elementary and

secondary school. In 1926, of Alcorn’s 702 students, 88

were in college, 377 in secondary school and 237 in

elementary school.17 Funding for Alcorn was severely limited

compared to the five white institutions. The state

appropriated over $7,000,000 between 1920 and 1930 for

buildings and permanent equipment at the six higher

education institutions. Alcorn received the least of any

institution — $364,000.18

I6Id. at 224. The Superintendent reported that, "no one who is

familiar with conditions in Mississippi would contend for a moment that

public education in the rural districts would be possible on any satisfactory

scale without transportation," id. at 60, and noted that the state provided

$2,166,842 for transportation in 1929-30. Yet the comparison of the total

number of vehicles available for transportation in school year 1930-31

reveals a shocking 4245 for whites compared to 27 for blacks. Id. at 57-

58.

I7Bureau of Education, United States Department of the Interior,

Survey o f Negro Colleges and Universities 405, 416-17 (1929).

18Twenty Years o f Progress, supra note 14 at 31. See also, Trueheart,

supra note 10 at 265, 266. The pattern of disparity in elementary and

secondary schools also continued through the 1930’s, with the state

reporting expenditures of $6.8 million for the instruction of white children

in 1937-38, while spending $1.3 million for black children. Twenty-five

(continued...)

10

In May of 1940, the state assumed control of Jackson

College for the purpose of training black teachers

(PA 113a).19 In 1946, the legislature established Mississippi

Valley State University for the education of black teachers

and for vocational training for black students. Mississippi

Valley began operating in 1950. (PA 113a-114a).

Four years later, this Court struck down racial

segregation in the nation’s public schools. Brown v. Board

o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). That same year,

defendant Board of Trustees issued a report entitled, "Higher

Education in Mississippi," commonly referred to as the

"Brewton Report." (PX 200 and USX 29). The report, which

describes blacks as a "substandard culture group," id. at 127,

18(...continued)

Mississippi counties had no high school for blacks. State Superintendent

of Public Education, Biennial Report and Recommendations to the

Legislature o f Mississippi fo r the Scholastic Years 1937-38 and 1938-39

15, 89-95 (1939).

19In his 1937 report, the Superintendent of Education reported that

Jackson College had been offered to the state free of charge provided the

state operate it as a teacher training institution for blacks. Id. When the

legislature approved the operation of the school, it downgraded it from a

college to the "Mississippi Negro Training School," and the school’s

president became a principal. 1940 Miss. Laws 352. The school’s

curriculum was reduced from a four-year to a two-year curriculum, but in

1944, the legislature renamed the school Jackson State College for Negro

Teachers and the four-year curriculum was restored. 1944 Miss. Laws ch.

159; N. McMillen, Dark Journey 107-08 (1989).

11

concluded that the goal of educational equality for black

citizens of Mississippi was "still very distant." Id. at 146.

Linking higher education with elementary and secondary

education, the Board stated:

The quantity and quality of higher education is so

inextricably bound to that on the lower level,

particularly the secondary level, that it is not possible

to consider inequalities in higher education at the

exclusion of others. Opportunities for the Negro

youth to get the basic secondary school training

necessary for college admission have been

considerably less than for the white youth of the

State.

Id. at 146.20

The Board Report found that " [e]ven greater inequalities

exist in the area of higher education." Id. at 148. The

opportunities provided in the black colleges were limited to

teacher education, agriculture, mechanical arts, practical arts

and trades, while the five white colleges provided "a variety

“The report showed that for school year 1952-53 there were 398,866

white children of school age and 496,913 black children of school age

(almost 100,000 more blacks), yet there were 452 high schools for whites

and only 247 for blacks (most of which were unaccredited); almost 70%

of the black teachers had two years or fewer of college training compared

to 7.5% of the white teachers; average salaries of white teachers with all

levels of training exceeded those of blacks with corresponding training;

only 20% of the total spent on transportation was used for blacks; and

72% of the expenditures for instruction went to whites -- $23,536,022

compared to $8,816, 670. (PX 200 at 139, 146-47).

12

of undergraduate programs" and "extensive offerings on the

graduate and professional levels," id. ; salary range for blacks

was lower in all ranks than the range for whites; of the total

funding for higher education for the period 1952-54, only

15.7% was allocated for blacks; and, blacks were compelled

to leave the state for graduate and professional study. Id.

In September of 1954, Medgar Evers, a black person,

applied to attend the University of Mississippi Law School.

The Board rejected his application and at that time imposed

a "race-neutral" alumni voucher requirement whereby each

applicant for admission had to submit five letters of

recommendation from alumni (USX 64 at 379-380). 1955

and 1956 passed with Mississippi’s separate and unequal

educational system intact.21

‘‘During the post -Brown period of "massive resistance," Mississippi

furiously enacted laws to negate the effect of Brown. See, e.g., Miss.

Const, art. VIII, § 213-B (1954) (permitting the legislature to abolish all

public schools in the state); Act of Feb. 24, 1956, 1956 Miss. Laws 366

(repealing the compulsory education laws); Resolution of Interposition,

1956 Miss. Laws 741 (Feb. 29, 1956) (declaring Brown and similar

decisions null and void within the territorial limits of the state of

Mississippi); Act of April 5, 1956, 1956 Miss. Laws 303 (giving effect to

the Resolution of Interposition and to the principle of racial segregation);

Act of April 5, 1956, 1956 Miss. Laws 337 (maintained racially separate

school districts); Act of April 4, 1955, 1955 Ex. Sess. 133 (prohibiting

whites and blacks from attending the same state funded high schools).

13

In 1961, James Meredith applied for admission to the

University of Mississippi. The Registrar rejected his

application on February 4, 1961. (PA 120a.) Three days

later the Board required all persons seeking admission to the

eight institutions of higher education to take the ACT.

Shortly thereafter the Board reaffirmed the alumni voucher

requirement, and authorized each institution to set a minimum

ACT score for admissions. (PA 120a-121a.) The Mississippi

Legislature approved the establishment of ACT minimum

scores with the proviso that the minimum scores "need not be

uniform between the various institutions" (USX 636, p. 16),

By 1963, there was "a gentleman’s agreement" that the three

largest HWIs would require a 15 on the ACT (Tr. 3350 (T.

Meredith)). By 1966, Delta State also required a minimum

score of 15 on the ACT for admission (Tr. 3507-08).22

22Thus, with the exception of the University of Mississippi and the

admission of Meredith by court order, each of these institutions adopted

an ACT minimum score requirement prior to admission of their first black

student. See infra note 31. Since at least 1954 Mississippi had recognized

that reliance on standardized tests scores might discriminate against blacks

because of the history of inequality. The Brewton Report concluded that

"much caution should be exercised in interpreting the results o f standard

tests administered to Negro children." PX 200 at 139 (emphasis added).

14

Meredith successfully challenged the rejection of his

application. The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit found

a "policy of planned discouragement and discrimination."

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 342, 346 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

371 U.S. 828 (1962). The court described the alumni

voucher requirement as "[o]ne of the most obvious dodges"

of the desegregation mandate. Id. at S52.23

Mississippi strenuously resisted the order to admit

Meredith. Authorized by the Board of Trustees to handle the

matter, Mississippi’s Governor Ross Barnett, in defiance of

an order of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit,

invoked Mississippi’s Resolution of Interposition24 and

personally blocked Meredith’s registration on September 25,

1962. Lieutenant-Governor Paul Johnson, Jr., repeated this

action the following day.25 In response, President Kennedy

ordered United States Marshals, subsequently supplemented

23The court did not consider the ACT requirement because it was not

applied to Meredith as a transfer student.

241956 Miss. Laws 741 (Feb. 29, 1956).

25United States v. Barnett, 330 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1963) (en banc)-,

United. States v. Barnett, 376 U.S. 681, 686 (1964). Both were held in

contempt of court. Id.

15

with federalized Mississippi National Guardsmen and regular

army troops26 to enforce the court’s order.27 Ultimately,

Meredith registered at the University on October 1, 1962,

accompanied by United States Marshals. There he studied

"under continuous guard until his graduation."28

II. The Separate and Unequal System o f Higher

Education Remains Substantially Intact: 1962-1987

In the post-Meredith period, black Mississippians faced

continued opposition to efforts to avail themselves of

educational opportunities available at Mississippi’s white

institutions. On June 4, 1963, Cleve McDowell was forced

to obtain a federal court order to gain admission to the

University of Mississippi Law School.;29 Again, in 1964,

black student Cleveland Donald had to obtain a court order

26United. States v. Barnett, 330 F,2d at 380; United States v. Barnett,

376 U.S. at 686. See also C'. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career o f

Jim Crow 174-75 (3rd revised ed. 1974).

27The federal forces faced armed opposition and a night-long battle

ensued in which Marshals tried to control the crowd with tear gas; two

people were killed, 375 injured (166 of them Marshals, 29 by gunshot

wounds). United States v. Barnett, 376 U.S. at 686; Woodward, supra

note 26, at 175. See also T. Branch, Parting the Waters, America In the

King Years 1954-63 647-53, 656-72 (1988).

28United States v. Barnett, 376 U.S. at 686.

29McDowell v. Tubb, No. 3425 (S.D. Miss. June 4, 1963); USX 636,

p. 21.

16

allowing his admission to the University of Mississippi.30 In

March of 1966, the Mississippi College For Women refused

to consider applications of six black women. The women

were forced to file a complaint with the Mississippi Council

on Human Relations (USX 913, S. 773).31

The decade of the 1960’s brought little in the way of

change in the elementary and secondary schools, whose

students, faculty and staff remained rigidly segregated until at

least the 1970-71 school year.32 With the first real movement

toward desegregated schools in 1970 came the rapid creation

and enlargement of racially segregated private academies,

}0Donald v. Tubb, No. 3583 (S.D. Miss, June 10, 1964); USX 636,

p. 21.

^Mississippi’s HWIs enrolled their first black students in the following

years: University of Mississippi (1962), Mississippi State University

(1965) , Mississippi University for Women (1966), Delta State University

(1966) , University of Southern Mississippi (1967) (PA 116a). The HBIs

enrolled their first white students in the following years: Alcorn State

University (1966), Jackson State University (1969), Mississippi Valley

State University (1970) (PA 117a).

nSee United States v. Hinds County School Bd., 417 F.2d 852 (5th

Cir. 1969) (per curiam), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 1032 (1970), delaying

order rev’d sub nom. Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. ofEduc., 396 U.S.

19 (1969).

17

which Mississippi supported through tuition grants, tuition

loans, and free textbooks.33

In the winter of 1969-70, the Office for Civil Rights

("OCR") of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare

notified Mississippi that it was operating a segregated system

of higher education in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, and asked that the state submit a desegregation

plan within 120 days. Mississippi did not respond.34

In 1973, OCR again advised the state that its higher

education system was in violation of Title VI and asked the

state to submit a desegregation plan (USX 407, p .l) . OCR’s

November 10, 1973 letter to the state in response to the first

plan submitted sets out the findings of OCR’s investigation of

the state system. These findings were not disputed at trial.

33Each such strategy to provide public support for a private

segregated system had to be challenged by black citizens. Norwood v.

Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973) (Burger, J.)(textbooks); Coffey v. State

Educ. Finance Comm., 296 F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss. 1969)(tuition

grants) (unpublished order in same case entered Sept. 2, 1970 prohibiting

tuition loans).

uAdams v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp. 92, 94 (D.D.C.), aff’d, 480

F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (en banc).

18

OCR concluded that the state’s actions since the early

1970’s served to reinforce and perpetuate the dual system. In

comparing the two land-grant colleges, OCR found:

Since 1971 Alcorn has constructed or begun to

construct faculty housing, an agricultural building, a

student union expansion, and student dormitories;

M .S.U. has constructed or begun to construct a

library annex, a forest products utilization laboratory,

a veterinary science building, an entomology

complex, a dairy sciences building, and a seed

technology building.

Id. at 5. OCR concluded that the construction since 1971

"reinforced the different agricultural capabilities of the two

institutions and generally has increased the disparity between

their physical plants." Id.

Alcorn also suffered in comparison to the University of

Southern Mississippi, the only other four-year institution in

the southern portion of the state. OCR found that,

[s]ince 1970 U.S.M. has initiated or reorganized 21

academic programs, begun a three-year Bachelor

Degree program, and upgraded two resident centers

to degree-granting branches, one of which is close to

Alcorn in the southwestern comer of the State. In

the same period Alcorn has approved nine new

majors. Thus U.S.M. currently grants 15 Bachelor

Degrees in 8 divisions, covering 105 majors; Alcorn

grants 2 Bachelor Degrees covering 30 majors.

19

Id. at 5 (emphasis added). In addition to increasing

disparities between the HBIs and the HWIs, OCR also found

that the HWIs were adding programs designed to duplicate

those offered by HBIs. While Jackson State had expanded its

offerings in the education field, the University of Mississippi

just created 6 new departments out of its former

School of Education. This duplication of most of

Jackson’s programs in education appears to represent

a substantial disincentive for white students to attend

Jackson, although Jackson’s growth in this area could

have attracted such students.

Id. at 6.

OCR also concluded that the faculties and student bodies

remained rigidly segregated. Id. at 2-4. Finally, OCR found

Mississippi’s then proposed plan of compliance inadequate,

noting that it "states policies of prospective nondiscrimination

. . . without detailing actions which will eliminate the effects

of past racial segregation." Id. at 7 .35

After OCR rejected Mississippi’s revised Plan of

Compliance in 1974, Mississippi nonetheless announced its

33During this period, the Mississippi Cooperative Extension Service,

a division of Mississippi State University was discriminating against blacks

in employment and promotion activities. Wade v. Mississippi Coop.

Extension Serv., 372 F. Supp. 126 (N.D. Miss. 1974), aff'd in relevant

pan, 528 F.2d 508, 518, 519 (5th Cir. 1976).

20

intent to implement the plan. One glaring omission in the

plan was the failure to address admissions standards at HWIs.

(USX 1; BDX 20). Thereafter, in January of 1975, black

citizens of Mississippi filed this action, and on April 21,

1975, the United States intervened; both complaints identified

the admission standards as discriminatory.

In 1975-76, the Board began to reexamine its admissions

standards, Tr. 3550 (T. Meredith), and in the process was

provided with numerous objections to the use of a minimum

ACT score as the sole criterion for admission,36 including the

fact that a survey of 15 major universities in 13 Southern and

36Board documents reveal the following possible objections (USX 56):

1. High school grades have provided the best single predictor of

college success. However, it is the consensus of opinion that

aptitude test scores along with high school grades will give a

better projection of college success in the first year of

performance. [See PPA 110 (ACT confirming that grades and

ACT scores combined are a better predictor of success in

college than ACT scores alone)]

2. Standardized tests are generally considered to have a degree of

cultural-ethnic bias.

3. The historically black institutions are committed to upgrade

those citizens with the greatest educational deficiencies.

4. Allocation of resources is related to enrollment and production

of student credit hours.

5. Substantial federal grants are available for special service

programs (remedial) at institutions of higher learning.

21

border states revealed that none relied on test scores alone for

admissions decisions and that 13 used high school grades in

the admissions process (USX 56).37

On May 20, 1976, the Board adopted admissions policies

requiring, for the 1977-78 school year, that the eight

universities limit enrollment of entering freshman to those

scoring nine or above on the ACT. The policy required that,

[tjhose institutions which presently have an entrance

standard requiring a higher [than 9] ACT score must

maintain that minimum admission score.

(USX 48) (emphasis added). Thus, the institutions primarily

affected by the 1976 policy were the HBIs, which previously

had no minimum ACT score requirements.38

On February 17 and December 15, 1977, the Board

amended the exceptional admission policy, limiting the

number of students who could be admitted with ACT scores

37At this time the four HWIs utilizing a 15 cut-score on the ACT had

probationary admissions policies for students with ACT scores below 15.

None of these institutions had numerical restrictions on the number of

students that could be admitted on probationary status (USX 39 pp.4-5).

38The HWIs previously had admitted relatively small numbers of

students in the 9-14 ACT score interval (BDX 176, 177). For example,

while 25,818 students attended HWIs in 1972 (USX 407, p.3), the five

HWIs admitted only 485 students (1.8%) with scores below 15 for the

following academic year (BDX 176).

22

between 9 and 14 (USX 48). Although each of the HBIs

already maintained lower minimum score requirements for

regular admission, the Board assigned each of them much

more expansive exceptional admissions roles, while none of

the HWIs was authorized to allow substantial numbers of

exceptional admissions.39

In 1981, the Board adopted new mission designations for

the eight universities (PX 316), dividing them into

comprehensive, urban and regional categories.40 Id.

39The HWIs may only enroll students with ACT scores below 15

through the exceptional admissions program; the total number admitted

may not exceed 5% of the previous years freshman enrollment or 50

students whichever is greater (PA 127a). The number of students admitted

under this program is further restricted by the fact that schools are not

required to use their exceptional enrollment slots (Mississippi University

for Women did not use any for the period 1982-83 to 1986-87) (BDX 173,

p.6); HWIs often publicize the 15 requirement but not the exception

(PA 52a., n. 12. USX 967, pp. 82-84, BDX 141, BDX 161), and at least

one HWI does not encourage those with scores below 15 to apply

(Tr. 3467). The cumulative result of these restrictive admissions policies

is that few exceptional admissions are granted. For example, in the fall

term of 1984, only 250 of the 3,545 (7%) freshman admitted to HWIs

came in under the policy, and only 101 of those 3,545 (2.8 %) were black.

(PX 277, Tr. 4361) (offer of proof).

^The Board assigned three historically white institutions (University

of Mississippi, University of Southern Mississippi, and Mississippi State

University), the broadest mission as "comprehensive universities" with

substantive leadership roles in designated areas. Jackson State University

was designated as an "urban university," and two HBIs (Alcorn and

Mississippi Valley), along with the two smallest HWIs (Delta State and

Mississippi University for Women), were designated "regional

universities." PX 316.

23

Defendants admitted (Tr. 3656 (T. Meredith)), and the en

banc majority found that mission designations locked in the

existing disparities and inequities among the various

institutions:

[T]he disparities are very much reminiscent of the

prior system. The inequalities among the institutions

largely follow the mission designation, and the

mission designations to some degree follow the

historical racial assignments.

(PA 37a).41

These disparities and continued segregation are well-

documented in the panel opinion.42

41Board witness, Dr. Thomas Meredith, testified that the mission

designations precluded Jackson State from developing additional doctoral

programs, but allowed it to continue with its one doctoral program in

education. "I don’t believe it encouraged Jackson State for further

development in the doctorial (sic) arena. We already had three institutions

doing that." Tr. 3649, T. Meredith. The mission designations also

precluded Alcorn and Mississippi Valley from going beyond the master’s

degree level and limited the number of masters degree programs available

to them. Delta State already offered degrees at the specialist and doctorate

level, and Mississippi University for Women offered programs at the

specialist level. Tr. 3654-55, T. Meredith.

42For example, salaries are higher at the HWIs than at the HBIs with

Jackson State’s salaries — the urban university — in line with those of the

two historically white "regional" universities; the two historically black

regional universities have the lowest salaries in the state; program

offerings are much broader at the three largest HWIs and the two regional

HBIs have the most limited programs in the state; the comprehensive

universities receive the most funds per student credit hour, the regionals

the least, and Jackson State is in the middle; the average total education

and general expenditures per student in 1986 at HWIs was $8,516

compared to $6,038 at HBIs; the replacement value of the facilities at the

(continued...)

24

The combination of the 15 ACT minimum score

requirements and the narrow exceptional admissions

provisions at the HWIs, work together with the mission

designations to lock in past disparities. Today, Mississippi

sends 86% of its white students to the three overwhelmingly

white "comprehensive" universities that on every substantive

measure are much better supported than the HBIs which 71%

“ (...continued)

two historically black "regional" institutions are the lowest in the state,

with Jackson State slightly above the two historically white "regional"

• institutions but far below the lowest "comprehensive" institution (almost

half the value); faculty, staff and students remain segregated by race (PA

50a-51, 55a-68a). As of trial, of the 13 members of the Board of

Trustees, three were black (PA 166a-167a). With respect to the regional

universities in particular, Delta State fares better than Alcorn or

Mississippi Valley on almost any measure, and is fairly comparable to

Jackson State on most measures. See PA 56a, 59a-61a, 68a. The

Mississippi University for Women, is not a good model for comparison

because of its small size and primary mission to serve a population that

historically also has been accorded second-class treatment in education.

See Mississippi Univ. fo r Women v. Hogan, 458 U.S. 718, 727 n.13

(1982).

Problems of continuing segregation at the elementary and secondary

level also persisted during the period. For example, the Natchez,

Mississippi school system was desegregated for the first time in the 1989-

90 school year. United States v. Natchez Special Mun. Separate School

Dist., No. 1120(W) (S.D. Miss. July 24, 1989)(unpublished). See also

United States v. Pittman, 808 F.2d 385, 386 (5th Cir. 1987) (over 70%

of Hattiesburg’s elementary schools remained segregated); United States

v. Lawrence County School Dist., 799 F.2d 1031, 1040 (5th Cir. 1986)

(over 50 % of the elementary students were attending racially identifiable

schools); United States v. Mississippi, 567 F.2d 1276, 1277 (5th Cir.

1978) (per curiam) (five out of seven elementary schools were virtually

one race schools); United States v. Columbus Mun. Separate School Dist.,

558 F.2d 228, 229 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1013 (1978)

(half of the elementary schools were racially identifiable).

25

of its black students attend.43 Thus, profound racial disparity

and segregation continue to be the hallmarks of Mississippi’s

higher education system.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Mississippi’s higher education system violates 34 C.F.R.

§ 100.3(b)(6)(i), which requires that states which operated de

jure segregated educational systems take "affirmative action

to overcome the effects of past discrimination." The

regulation has the force of law and clearly requires more than

the adoption of good-faith, race-neutral policies. This is

evident from 1) the plain language of the regulation, 2) the

fact that it was adopted in 1973, after it was already clear

that Title VI and the existing regulations required race-

neutral policies, 3) an illustrative application in 34 C.F.R. §

100.5(h) indicating that "additional steps" beyond race

neutrality are required, and 4) the HEW interpretive

guidelines which enumerate a variety of affirmative remedial

steps.

43PPA 137; USX 880. Ninety-nine percent of Mississippi’s white

students attend HWIs. Id.

26

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986) does not

compel the opposite result, for Bazemore presented a radically

different factual setting. Moreover, unlike Bazemore, where

the Court placed heavy emphasis on the federal government’s

position that North Carolina had complied with the applicable

Department of Agriculture regulations, in Ayers the

government has never maintained that Mississippi has

complied with § 100.3(b)(6)(i).

Mississippi is also in violation of the equal protection

clause, which imposes upon the state an affirmative duty to

eliminate "root and branch" the vestiges of its dual system.

This obligation to take measures to undo past discrimination

has always been a central tenet of school desegregation

jurisprudence. It is logical and necessary that the affirmative

duty be applied to higher education because, as the Court

concluded in Green v. New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430

(1968), to do otherwise would leave in place the very

discrimination condemned in Brown. Mississippi has not

satisfied its affirmative duty because it continues to operate

under a dual structure shaped by intentional discrimination.

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985). In addition to

27

failing to eliminate continuing intentional discrimination, the

state has failed to eliminate the vestiges of the dual system

which present a continuing barrier to equal educational

opportunity. The finding of the en banc majority that further

dismantling of the racially dual structure would eliminate

diversity among institutions and student choice was in error.

The diversity and choice present in the Mississippi system

today are legacies of the previous regime of de jure

segregation and cannot be protected. As a remedy hearing

would demonstrate, true diversity and choice, free of

discriminatory stigma, are fully compatible with Brown’s

mandate of educational equality.

ARGUMENT

I. M is s is s ip p i’s D u ty U n d er 3 4 C .F .R . § 1 0 0 .3 ( b ) (6) (i)

To "Take A ff ir m a tiv e A c tio n To O verco m e T he

E ffe c ts O f P r io r D isc r im in a tio n " I s N o t S a tis f ie d B y

A b a n d o n in g E x p ress ly D isc r im in a to ry P o lic ie s

W h ere M is s is s ip p i’s P r io r D isc r im in a tio n C o n tin u e s

to H a v e E ffe c t.

A. Petitioners’ Regulatory Claim Is Properly

Considered Prior to the Constitutional Claim.

This Court has maintained consistently that where

constitutional and nonconstitutional claims are presented, it

will first address the nonconstitutional claim where to do so

28

might obviate the need to consider the constitutional issue.

See Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Auth., 297 U.S. 288, 347

(1936) (Brandeis, J. concurring).44 Ayers’ Petitioners have

pressed their claim under 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i) at each

stage of this litigation,45 however, the lower courts have failed

to address it adequately.46

B. 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i) Has The

Force O f Law.

Mississippi’s system of higher education is in violation of

34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i), which provides:

In administering a program regarding which the

recipient has previously discriminated against persons

on the ground of race, color, or national origin, the

recipient must take affirmative action to overcome

the effects of prior discrimination.

44Accord United States v. Wells Fargo Bank, 485 U.S. 351, 354

(1988); Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 60 (1980); New York City Transit

Auth. v. Beazer, 440 U.S. 568, 582 (1979).

4SSee e.g., District Court: Private Plaintiffs’ Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law at C-l. Court of Appeals: Brief for Plaintiffs-

Appellants at 56 & n.106, 64 & n.123, 66-67 & n.126. U.S. Supreme

Court: Ayers Petitioners’ Petition for Writ of Certiorari at i, and 41-43.

46The district court referred generally to the Title VI regulations but

did not apply § 100.3(b)(6)(i) (PA 168a, 182a-184a). The en banc

majority addressed the regulatory claim in a cursory manner (PA 26a,

n .l l ) . The district court apparently applied § 100.3(b)(2) with respect to

the ACT minimum score requirement (PA 182a), but did so improperly

because it held that the ACT cut-score was valid even if there were less

exclusive alternatives that were educationally sound (PA 182a). Compare

Albermarle v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 425 (1975).

29

(PPA 89).47 The regulation was promulgated pursuant to

§ 602 of Title VI which provides, in relevant part:

Each Federal department and agency which is

empowered to extend Federal financial assistance to

any program or activity, by way of grant, loan, or

contract . . . is authorized and directed to effectuate

the provisions o f section 2000d o f this title with

respect to such program or activity by issuing rules,

regulations, or orders o f general applicability.

42 U.S.C. § 2000d-l (emphasis added).48

This Court has held that where Congress expressly

delegates to an agency the power to implement a statute, as

it did in § 602, Congress entrusts to the agency rather than

the courts primary responsibility for interpreting the statute.

Moreover, substantive rules adopted pursuant to that

delegation have the force of law. See Chrysler Corp. v.

Brown, 441 U.S. 281, 301-03 (1979); Batterton v. Francis,

432 U.S. 416, 425 (1977).

47The regulation is both valid and applicable to Mississippi. The

district court found that Mississippi has a lengthy history of discrimination

in its higher education system (PA 114a-117a), and that its higher

education system receives federal funding (PA 169a, n.7).

48Section 602 requires that such regulations be signed by the

President. Id. President Nixon approved the adoption of § 100.3(b)(6)(i)

by 21 Federal agencies in 1973. 38 Fed. Reg. 17920 (July 5, 1973).

30

C. Where Continuing Discriminatory Effects o f the De

Jure System Exist, 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b) (6) (i)

Mandates Implementation o f Affirmative Measures

To Overcome Those Effects.

In its brief reference to the Title VI regulation, the en

banc majority ruled that the affirmative duty under

§ 100.3(b) (6) (i) is satisfied by "discontinuing prior

discriminatory practices and adopting and implementing good-

faith, race-neutral policies and procedures" (PA 26a).

Petitioners submit that this holding is in error.

The regulation requires more than simply the adoption of

race-neutral policies. It requires the adoption of affirmative

measures to eliminate the vestiges of Mississippi’s dual higher

education system. This conclusion is compelled by the plain

language of the regulation, its history, an illustrative example

in the regulations, and the HEW guidelines promulgated to

interpret the regulation.

1. The Plain Language of § 100.3(b)(6)(i)

A common sense reading of the regulation’s language,

which requires "affirmative action to overcome the effects of

prior discrimination," leads to a conclusion that more is

required than simply the adoption of policies of

31

nondiscrimination. If the affirmative action requirement

could be satisfied by adopting race-neutral policies, the

drafters would have indicated such, by directing recipients to

take, for example, "affirmative action to end previous

discriminatory practices." That explicit and stronger language

was used is an indication that strong steps are required.

2. The History of § 100.3(b)(6)(i)

The original Title VI regulations adopted in 1964 did not

include § 100.3(b)(6)(i). That section was added in 1973. 38

Fed. Reg. 17,979 (July 5, 1973). At that time, a

nondiscrimination edict already existed in both Title VI,

42 U.S.C. § 2000d, and the existing regulations, 29 Fed.

Reg. 16,299 (Dec. 4, 1964). Thus, the purpose of the

amendment to the regulation could only have been to make

clear that in certain circumstances more than

nondiscrimination was required. To view the 1973 addition

of an "affirmative action" provision as requiring nothing more

than race-neutral policies suggests that Title VI and the

original regulations did not themselves mandate

nondiscrimination policies. That position is not tenable.

32

3. The Illustrative Example

When § 100.3(b)(6) (i) was added to the HEW’s Title VI

regulations in 1973, the agency also added an "Illustrative

application," which provides, in relevant part:

In some situations, even though past discriminatory

practices attributable to a recipient or applicant have

been abandoned, the consequences of such practices

continue to impede the full availability of a benefit.

If the efforts required of the applicant or recipient

. . . have failed to overcome these consequences, it

will become necessary under the requirement stated

in [§ 100.3(b)(6)(i)] for such applicant or recipient to

take additional steps to make the benefits fully

available to racial and nationality groups previously

subject to discrimination. :

34 C.F.R. § 100.5(h). The "additional steps" must refer to

something more than race-neutral policies, for the steps

become necessary only when those policies alone have failed

to produce equal educational opportunity.

4. HEW Criteria Interpreting § 100.3(b) (6) (i)

In 1978, the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare (HEW) published its "Revised Criteria Specifying the

Ingredients of Acceptable Affirmative Action Plans to

Desegregate State Systems of Higher Education." 43 Fed.

Reg. 6658 (Feb. 15, 1978). While these guidelines do not

have the force of law, they "do constitute a body of

33

experience and informed judgment to which courts and

litigants may properly resort for guidance." Skidmore v.

Swift, 323 U.S. 134, 140 (1944); see Lau v. Nichols, 414

U.S. 563, 568 (1974) (court deferred to HEW memorandum

requiring schools to take affirmative steps to address needs of

bilingual children).49

The guidelines first affirm the conclusion that states with

a history of de jure segregation, "are required to take

affirmative remedial steps and to achieve results in

overcoming the effects of prior discrimination." 43 fed .

Reg. at 6659. The guidelines specify the nature of the

affirmative remedial obligation in a wide variety of areas.

Each element of the guidelines shares one feature: states are

required to do more than adopt race-neutral policies.50

49 See also Local 93, Int'lA ss’n o f Firefighters v. Cleveland, 478 U.S.

501, 517-18 (1986); Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57, 65

(1986).

50 For example, they specify that an acceptable desegregation plan

shall eliminate program duplication among HWIs and HBIs, adopt specific

goals and timetables to increase the number of blacks who enter and

graduate from HWIs and whites who enter and graduate from HBIs,

43 Fed. Reg. at 6662, and adopt specific goals and timetables to increase

the number of blacks on university governing boards, and on the faculty

and staffs of HWIs. Id. at 6661-62.

34

In summary, all of the available indicators ~ the

regulation’s plain language, its history, the illustrative

example, and the HEW criteria — compel the conclusion that