Marshall v Gavin Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

May 30, 1974

36 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Marshall v Gavin Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1974. 06466814-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c9482a79-7d60-4487-ac4f-7256a4125efe/marshall-v-gavin-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

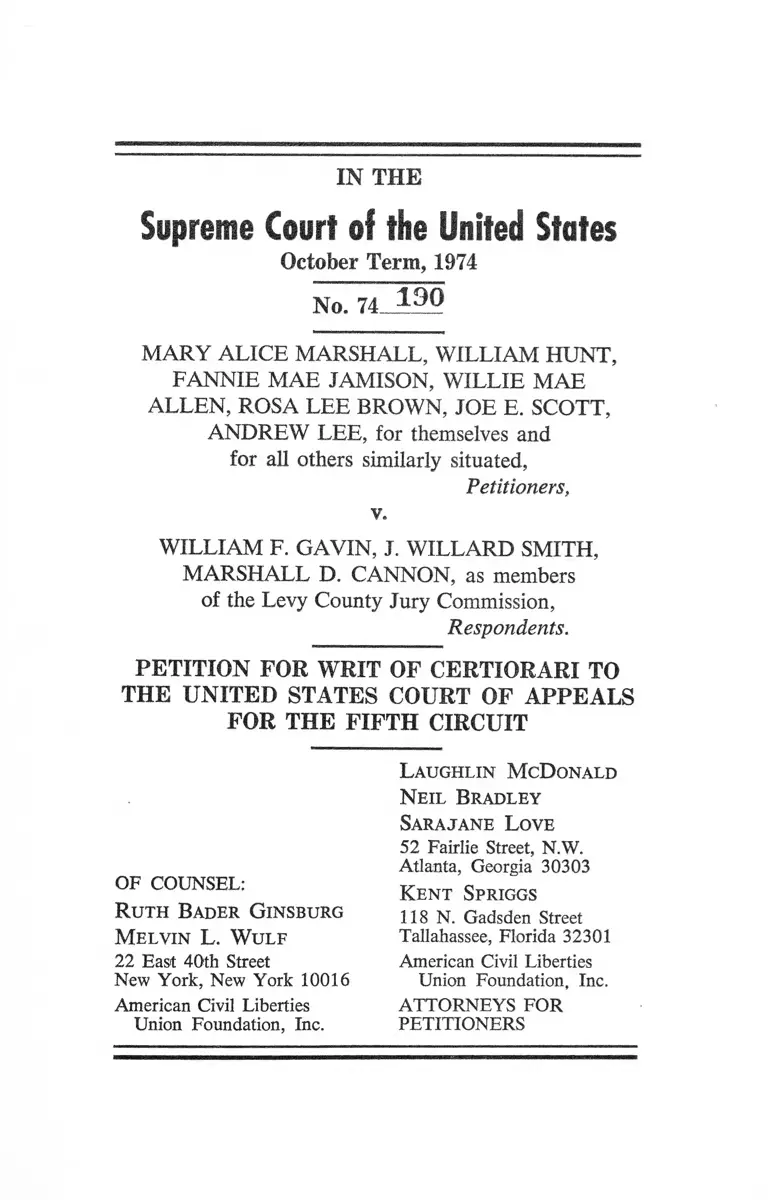

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1974

No. 7 4 _ 1 ? 9

MARY ALICE MARSHALL, WILLIAM HUNT,

FANNIE MAE JAMISON, WILLIE MAE

ALLEN, ROSA LEE BROWN, JOE E. SCOTT,

ANDREW LEE, for themselves and

for all others similarly situated,

Petitioners,

v.

WILLIAM F. GAVIN, J. WILLARD SMITH,

MARSHALL D. CANNON, as members

of the Levy County Jury Commission,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

OF COUNSEL:

R u t h B ader G in sburg

M e l v in L. W u l f

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

L a u g h lin M cD onald

N e il B rad ley

Sa r a ja n e L ove

52 Fairlie Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

K e n t Spriggs

118 N. Gadsden Street

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

ATTORNEYS FOR

PETITIONERS

INDEX

OPINIONS BELOV/...... ........................................... 2

JURISDICTION......................................................... 2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW......... 2

STATE STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE................................. 3

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT.......... 5

I. The decision below is inconsistent with

decisions of this court requiring close

judicial scrutiny of sex-based classifica

tions, and the reliance upon Hoyt v. Flor

ida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961), was misplaced......... 5

II. This case presents important issues con

cerning the composition of state court

juries and the equal sharing of jury service

• • by all adult members of the community....... 8

III. Jury selection in Levy County discrimi

nates against Negroes...................................... 10

CONCLUSION........................................................... 12

APPENDIX

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit............................................ la

Order Denying Motion for Leave to File a

Petition for Rehearing Out of Time................. 2a

Opinion of the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Florida................. 3a

Judgment................................................................... 13a

Stipulations of the Parties....................................... 14a

Page

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1971)........ 10

Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404 (1972)............ .. 7

Broadway v. Culpepper, 439 F.2d 1253

(5th Cir. 1971)................................................. 10, 11

Brooks v. Beta, 366 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966)........... 11

Carter v. Jury Commission o f Greene County,

396 U.S. 320 (1970).........................................10, 11

Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677

(1973). ......................................................... 5, 6, 7, 8

Healy v. Edwards, 363 F. Supp. 1110 (E.D.

La. 1973) (three-judge court),prob.jur.

noted, 415 U.S. 911 (1974)................................. 6,7

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961)..................5, 6, 7

Kahn v. Shevin, 42 U.S.L.W. 4591

(April 24, 1974).................................................... 6

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698

(5th Cir. 1966)...................................................... 10

Marshall v. Holmes, 365 F. Supp. 613 (N.D.

Fla. 1973), affirmed, 495 F.2d 1371 (5th

Cir. 1974)............................................................. 2

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1973)........................ 10

Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971)................. 5, 6, 7, 8

Rowe v. Peyton, 383 F.2d 709 (4th Cir. 1967),

affirmed, 391 U.S. 54 (1968)............................... 6

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970).................. 10

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole,

263 F.2d 71 (5th Cir. 1959)................................ 11

u

United States v. Zirpolo, 450 F.2d 424

(3rd Cir. 1971)..................................................... 7

White v. Crook, 251 F. Supp. 401

(M.D. Ala. 1966) (three-judge court)................ 7

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967)........ . 11

Constitution:

Fourteenth amendment of the Constitution

of the United States............................................ 3

Federal Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1254(1)................................................. 2

28 U.S.C. §2281..................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. §1981..................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. §1983..................................................... 3

State Statutes:

Alaska Stat. § §9.20.010, 9.20.030.......................... 9

Arizona Rev. Stat. Ann. §§21, 201, 21.202.......... 9

3B Ark. Stats. Ann. § §39.101 et seq..................... 9

13 Cal. Code Civ. Pro. §§198 et seq..................... 9

4 Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§78-1 et seq................... 8

10 Del. Code Ann. §§4505 et seq.......................... 9

Florida Statutes, §40.01(1)................................ 3, 4, 5

7 Hawaii Rev. Laws §§609-1 et seq...................... 9

2 Idaho Code Ann. §§2-201 et seq........................ 9

111. Ann. Stat. Ch. 78 § §1 et seq. (Smith Hurd). . 9

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Cont’d)

Page

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Cont’d)

Page

Ind. Ann. Stat. §4-7115.......................................... 9

Iowa Code Ann. §§607.1 et seq............................. 9

3A Kan. Stat. Ann. §§43-155 et seq...................... 9

1 Ky. Rev. Stat. §§29.205, 39.035..................... ... 9

14 Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§1201 et seq................... 9

5A Md. Ann. Code art. 51, § §1 et seq.................. 9

Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. §§600.1306, 600.1307. . 9

Miss. Code Ann. §§1762 et seq.............................. 9

7 Mont. Rev. Codes Ann. §§93-1301 et seq......... 9

1 Nev. Rev. Stat. §§6.010 et seq............................ 9

2A N.J. Rev. Stat. §§69-1, 69-2............................ 9

N.J. 5A §93-1304 (12)............................................ 9

4 N.M. Stat. Ann. §§19-1-1 et seq..

IB N.C. Gen. Stat. §§9-3 et seq....

5 N.D. Cent. Code §§27-09.1 et seq.

1 Ore. Rev. Stat. §§10.010 et seq...

17 Pa. Stat. §1279............................

7 S.D. Code §§16-13-10 et seq........

Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 12, App. VII,

Pt. 1, R.25 §27.............................

2 Va. Code Ann. §§8-208.2 et seq..

W. Va. Code Ann. §§52-1-1 et seq..

Wis. Stat. Ann. §§255.01, 270.16. . ,

Other Authorities:

Hayghe, Labor Force Activity of Married

Women, U.S. Department of Labor

Monthly Labor Review, Table 4 at 34

(April 1973).......................................................... 8

U.S. Women’s Bureau, Department of Labor,

Highlights of Women’s Employment &

Education (1973)................................................. 7

IV

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1974

No. 74

MARY ALICE MARSHALL, WILLIAM HUNT,

FANNIE MAE JAMISON, WILLIE MAE

ALLEN, ROSA LEE BROWN, JOE E. SCOTT,

ANDREW LEE, for themselves and

for all others similarly situated,

Petitioners,

v.

WILLIAM F. GAVIN, J. WILLARD SMITH,

MARSHALL D. CANNON, as members

of the Levy County Jury Commission,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners, Mary Alice Marshall, William Hunt, Fan

nie Mae Jamison, Willie Mae Allen, Rosa Lee Brown,

Joe E. Scott, and Andrew Lee, pray that a writ of cer

tiorari issue to review the judgment of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered on May

30, 1974.

1

2

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit affirming the judgment of dismissal

rendered by the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Florida is noted at 495 F.2d 1371

and is set out in the appendix, infra, at p. la. The opinion

of the United States District Court for the Northern Dis

trict of Florida is reported at 365 F. Supp. 613, and is

set out in the appendix, infra, at pp. 3a-12a.* A motion

for leave to file an out-of-time petition for rehearing was

denied by order of July 1, 1974, and is set out in the

appendix, infra, at p. 2a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit was entered on May 30, 1974. This

Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented For Review

1. Whether petitioners were entitled to have a three-

judge court convened to adjudicate the constitutionality

of the mothers’ exemption provision of Florida jury law

which provides for a sex-based right to opt-out of jury

duty in favor of expectant mothers and mothers with

children under 18 years of age.

2. Whether the mothers’ exemption provision of the

Florida jury laws places an unequal burden of jury duty

upon men and produces juries in Levy County which

do not represent a cross section of the community.

3. Whether Negro citizens have been discriminated

against in the selection of persons for jury service in

Levy County, Florida.

*The opinions below are rendered sub nom. Marshall v. Holmes.

3

State Statutory Provisions Involved

Florida Statutes, §40.01(1):

(1) Grand and petit jurors shall be taken from

the male and female persons over the age of twenty-

one (21) years, who are citizens of this state and

who have resided in this state for one (1) year and

in their respective counties for six (6) months and

who are fully qualified electors of their respective

counties; provided, however, that expectant moth

ers and mothers with children under eighteen (18)

years of age, upon their request, shall be exempted

from grand and petit jury duty.

Statement of the Case

Petitioners, a group of black men and women citi

zens, commenced this action on January 13, 1972, alleg

ing that blacks and women were underrepresented on

the Levy County, Florida juries, and that Florida Stat

utes, §40.01(1), which allows expectant mothers and

mothers with children under 18 years of age to opt-out

of jury service, was unconstitutional. Jurisdiction was

based on the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States, 28 U.S.C. §2281, 42 U.S.C. §§1981

and 1983. A three-judge court was requested and the

case adjudicated on stipulated facts. The district court

entered an opinion order on September 28, 1973, declin

ing to convene a three judge court concluding that the

constitutional challenge was insubstantial and resolving

all issues in favor of the defendants. The court of appeals

affirmed per curiam on May 30, 1974, adopting the

opinion of the district court.

The current system for jury selection in Levy County

was instituted in August, 1970. The respondent jury

4

commissioners compiled an eligibility file for jury ser

vice by mailing a questionnaire to all registered voters.

Those voters who were not qualified for statutory ex

emptions from jury duty as well as those who did not

respond to the questionnaire were placed in the eligibility

file. A total of 2,978 names were so compiled from

which 625 were selected on a random basis to be placed

in a box from which jurors’ names were drawn. As of

August, 1970, voter registration was 4,966 in Levy

County, of which 4,415 were white and 551 were black.

The racial and sexual composition of the eligibility file

at that time was as follows: 1,434 white males, 1,168

white females, 172 black males and 204 black females.

Subsequent to the initial composition of the eligibility

file, each newly registered voter has received a question

naire while each elector who has died or moved, if such

is made known to the jury commissioners, is eliminated

from the eligibility file.

The total number of women claiming the §40.01(1)

exemption for mothers and expectant mothers as of April

23, 1973, was 623. Of this number, 195 indicated that

they had employment outside the home.

Jury lists for 1971, 1972 and 1973 contained 7.64,

14.39 and 18.0 per cent blacks for an average of 12.97

per cent, and 36.31, 48.29 and 38.0 per cent women for

an average of 44.41 per cent respectively.1 The popula

tion of Levy County, Florida is 51 per cent female and

25.2 per cent Negro. *

xThe parties also stipulated that during 1969 12.81% of jury lists

were black and 39.41% were female. For 1970, 14.47% of the

lists were black and 25.0% were female. Thus, from 1969 through

February 27, 1973, the dates covered by the stipulation, an aver

age of only 40.3% of jury lists were female and 13.2% were black.

5

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I. The decision below is inconsistent with deci

sions of this Court requiring close judicial scrutiny

of sex-based classifications, and the reliance upon

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961), was misplaced.

The district court, affirmed per curiam on appeal,

concluded that a three-judge court was not required to

hear petitioners’ complaint that Florida’s exemption

from jury duty in favor of pregnant women and mothers

with children under 18 years of age was unconstitutional,

since the validity of Florida Statutes, §40.01(1) had

been settled by Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961)

Intervening decisions, however, have eroded the ruling

in Hoyt to the point where it is in plain conflict with

vibrant precedent subsequently established by this Court.

In Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), and Frontiero v.

Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973), this Court signaled

a new direction for resolving the constitutionality of

sex-based legislation. In Reed it invalidated an Idaho

statute that gave a preference to men over women for

appointment as estate administrators. Frontiero struck

down a scheme whereby military housing allowance and

medical benefits were automatically granted for service

wives while such benefits were disallowed for service

husbands unless the service member proved she supplied

over half her husband’s support. The synthesis of Reed

and Frontiero is that similarly situated men and women 2

2Hoyt involved a predecessor statute of §40.01(1) and concluded

that it was not unconstitutional to require women to opt-in for jury

service by registering with the Clerk of the Circuit Court “her

desire to be placed on the jury list.” Florida Statutes, 1959,

§40.01(1).

6

are constitutionally entitled to equal treatment by law

and that sex-based generalities will not sustain unequal

treatment absent the demonstration of a fair and sub

stantial justification for the differential.3 Classifications

such as those contained in the Florida mothers’ exemp

tion are now accorded careful review, and stereotypical

generalizations, once accepted as a matter of course or

given only cursory attention, no longer survive consti

tutional scrutiny. Frontiero v. Richardson, supra. In

Healy v. Edwards, 363 F. Supp. 1110, 1117 (E.D. La.

1973) (three-judge court), prob. jur. noted, 415 U.S.

911 (1974), a decision declaring unconstitutional Loui

siana’s opt-in plan for jury service for women identical

to the one approved in Hoyt, the court noted:

[Tjhere are occasional situations [such as Hoyt

v. Florida] in which subsequent Supreme Court

opinions have so eroded an older case, without ex

plicitly overruling it, as to warrant a subordinate

court in pursuing what it conceives to be a clearly

defined new lead from the Supreme Court to a con

clusion inconsistent with an older Supreme Court

case.4

Hoyt is indeed “yesterday’s sterile precedent” and it was

error for the court below to rely upon it. Ibid.

8Kahn v. Shevin, 42 U.S.L.W. 4591, 4593 (April 24, 1974), does

not signal a return to the day when this Court countenanced a

“sharp line between the sexes,” since the classification there in

volved collection of revenue, an area in which “the states have

large leeway in making classifications and drawing lines which in

their judgment produce reasonable systems of taxation.” Kahn

cannot be read to permit differential treatment of men and women

based on traditional notions of separate spheres for the two sexes,

for such an interpretation would collide head-on with Reed and

Frontiero.

4Quoting from Rowe v. Peyton, 383 F.2d 709, 714 (4th Cir. 1967),

affirmed, 391 U.S. 54 (1968).

7

The Florida statutory scheme establishes a sex-based

classification that stigmatizes all women, even those who

do not wish to serve, by decreeing, in effect that while

male participation in the administration of justice is essen

tial, participation by women is not. Identifiable groups

in the community may not constitutionally be excluded

from jury selection procedures, Apodaca v. Oregon, 406

U.S. 404, 413 (1972), and women are such an identi

fiable group. White v. Crook, 251 F. Supp. 401 (M.D.

Ala. 1966) (three-judge court); United States v. Zir-

polo, 450 F.2d 424 (3rd Cir. 1971); Healy v. Edwards,

supra. Florida’s jury selection statutes relegate women

“to inferior legal status without regard to [their] actual

capabilities.” Frontiero v. Richardson, supra, 411 U.S.

at 687. Women are thus branded as second class citizens

in violation of the right of their class to equal treatment.

Section 40.01(1) bears no substantial relationship to

any legitimate state objective. The Hoyt image of woman

“as the center of home and family life,” of dubious ac

curacy for many women in 1961, is today recognized

as a gross generalization of the same order as the familiar

stereotypes rejected as a basis for legislative classifica

tion in Frontiero and Reed. While the justification for

exemption from jury duty in favor of mothers with small

children is that they need to be at home caring for their

young, the reality of life for women with children in

Levy County is that of those exempted from jury service

as of 1973 31% had some form of employment outside

the home. As well, in 1972, 60% of all married women

in the United States living with their husbands were gain

fully employed and 42% of all working women were

employed full time the year round. U. S. Women’s Bu

reau, Department of Labor, Highlights of Women’s Em

8

ployment and Education (1973). In 1972, 26.9% of

the mothers with children under three years old were

in the labor force; 36.1% of mothers with children 3-5

years old were gainfully employed; and 50.2% of women

with children 6-17 years old were in the labor force.

Hayghe, Labor Force Activity of Married Women, U.S.

Department of Labor, Monthly Labor Review, Table 4,

at 34 (April 1973). The fact is that the Florida jury

service exemption for women covers a substantial popu

lation of mothers for whom child care concerns do not

preclude active involvement outside the home. The Flo

rida classification is overinclusive5 and under Frontiero

and Reed unconstitutional. Plaintiffs’ attack upon it was

substantial and should have been heard by a three-judge

court.

II. This case presents im portant issues concern

ing the composition of state court juries and the

equal sharing of jury service by all adult members

of the community.

Men and women similarly situated who are responsi

ble for the care of children are not treated similarly by

Florida jury law. There is no reason for treating them

differently. The Florida statute fails to exempt men with

child care responsibilities, among them widowed fathers

and husbands with incapacitated wives. For these men

jury service may be far more burdensome than it is for

women. More appropriate means are obviously avail

able to further a genuine concern for care of children.

5It is also underinclusive to the extent that it excludes fathers with

children under eighteen. In this respect, it conclusively presumes

the mother will be the child tenderer, a decision which family pri

vacy requires be left to the individuals involved, and not steered

by the state.

9

For example, recognizing that child rearing is a function

either parent can perform, New Jersey exempts any “per

son” who has custody of and personal care for a child.

N.J.S.A. §93-1304(12). The experience of the federal

courts and 30 states that administer jury selection meth

ods which are non-discrimin atory on their face, suggest

that there is in fact no justification for the statute here.6

The disproportionate jury service cast upon men by

the mothers’ exemption also ensures that juries in Levy

County do not reflect a cross section of the community.

While 51 % of population of Levy County is female, from

1969 to 1973 an average of only 40% of the jury lists

were female. Moreover, 623 (31%) of the women eligi

ble for service (assuming they had no other basis for

being exempt) used the mothers’ exemption to escape

jury duty. And 195 of the 623 were employed outside

the home. The disparity here is not the product of chance

but the direct result of the “benign dispensation” ac

corded women by Florida law, a dispensation which

operates to place a disproportionate burden upon males

and ensure non-representative juries. Jury service is * 111

6See Alaska Stat. §§9.20.010: 7 Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§21.201,

21.202; 3B Ark. Stats. Ann. §§39.101 et sea.; 13 Cal. Code Civ.

Pro. §§198 et sea.: 10 Del. Code Ann. §§4505 et seq.; 7 Hawaii

Rev. Laws §§609-1 et seq.; 2 Idaho Code Ann. §§2-201 et seq.;

111. Ann. Stat. ch. 78 §§1 et seq. (Smith-Hurd); Ind. Ann. Stat.

§4-7115: Iowa Code Ann. §§607.1 et sea.; 3A Kan. Stat. Ann.

§§43-155 et seq.; 1 Ky. Rev. Stat. §§29.025, 29.035; 14 Me. Rev.

Stat. Ann. §§1201 et seq.; 5A Md. Ann. Code art. 51, §§1 et seq.;

Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. §§600.1306, 600.1307; 2 Miss. Code Ann.

§§1762 et seq.; 1 Mont. Rev. Codes Ann. §§93-1301 et seq.; 1 Nev.

Rev. Stat. §§6.010 et seq.; 2A N.J. Rev. Stat. §§69-1, 69-2; 4

N.M. Stat. Ann. §§19-1-1 et seq.; IB N.C. Gen. Stat. § §9-3 et seq.;

5 N.D. Cent. Code §§27-09.1 et seq.; 1 Ore. Rev. Stat. §§10.010

et seq.; 17 Pa. Stat. §1279; 7 S.D. Code §§16-13-10 et seq.; Vt.

Stat. Ann. tit. 12, Apn. VII, Pt. 1, R.25 §27; 2 Va. Code Ann.

§§8-208.2 et seq.; W. Va. Code Ann. §§52-1-1 et seq.; Wis. Stat.

Ann. §§255.01, 270.16.

10

not simply a right, but it is a duty, a “crucial citizen

responsibility]” which should be shared by all men

and women. Broadway v. Culpepper, 439 F.2d 1253,

1258 (5th Cir. 1971).

Whether Florida’s mothers’ exemption accomplishes

discriminatory treatment by virtue of its facial operation

or its discriminatory impact, it should be closely scruti

nized by this Court. The propriety of close scrutiny flows

not only from the fact that the statute embodies a sex-

based classification, but from the fact that it abridges

the fundamental rights of all citizens to equally shared

jury service and trial by representative juries. “ [Exclu

sion of a discernible class from jury service . . . destroys

the possibility that the jury will reflect a representative

cross-section of the community.” Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S.

493, 500 (1972). III.

III. Ju ry selection in Levy County discriminates

against Negroes.

In Levy County the population is 25% black. The

list of persons from which venires are chosen has varied

between 7% and 18% black from 1969 to 1973, for

an average of 13.2%. Negro citizens thus have been

underrepresented by approximately 50%. This disparity

is more dramatic statistically than the showing in Turner

v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970), and it was sufficient

to establish a prima facie showing of systematic exclu

sion. See Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1971);

and Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, 396

U.S. 320 (1970).

While petitioners in the district court attacked the

use of voter rolls in Florida as the sole source for the

11

names of jurors, a constitutional jury list may be com

piled in Levy County without disturbing the source of

names of jurors.7 Overrepresentation of whites and un

derrepresentation of blacks could be corrected by draw

ing Negro citizens at a higher rate than whites for jury

service. See Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966).

And while Florida statutes do not permit other sources

to supplement the voter rolls, where the federal Consti

tution commands that juries be representative, no im

pediment or barrier to supplementing the list of voter

rolls should exist. Nothing contained in Carter or any

of the cases relied upon below requires this Court to

condone continued and exclusive use of underrepresenta

tive voter rolls which yield underrepresentative juries.

The constitutional end sought is not use of any particu

lar lists, but juries which represent a cross-section of the

community. Broadway v. Culpepper, 439 F.2d 1253,

1257 (5th Cir. 1971).

7This Court has approved the use of voter lists as the source of

names for jurors, but the use of voter lists which are themselves the

product of discrimination should not be countenanced. United

States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71, 78 (5th Cir. 1959).

Cf. Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967).

12

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons the petition for writ of

certiorari should be granted.

OF COUNSEL:

R uth Bader G insburg

M elvin L. Wulf

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

Respectfully submitted,

L aughlin M cD onald

N eil Bradley

Sarajane L ove

52 Fairlie Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Kent Spriggs

118 N. Gadsden Street

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

ATTORNEYS FOR

PETITIONERS

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-3849

Summary Calendar*

MARY ALICE MARSHALL, ET AL.,

For themselves and for all

others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-A ppellants,

VERSUS

DONALD HOLMES, ET AL., Etc.,

Defendants-A ppellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Florida

(May 30, 1974)

Before COLEMAN, DYER and RONEY,

Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

We affirm the judgment of the district court for the

reasons set forth in its adjudication 365 F. Supp. 613.

See Local Rule 21.1

*Rule 18, 5 Cir., see Isbell Enterprises, Inc. v. Citizens Casualty

Company of New York, et al., 5 Cir. 1970, 431 F.2d 409, Part I.

JSee NLRB v. Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, 5 Cir.

1970, 430 F.2d 966.

la

2a

Filed July 1, 1974.

In the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. S73-3849

Mary Alice Marshall, et ah, for themselves

and for all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-A ppellants,

versus

Donald Holmes, et al., Etc.,

Defendants-A ppellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Florida

Before COLEMAN, DYER and RONEY,

Circuit Judges.

BY THE COURT:

IT IS ORDERED that appellants’ motion for leave

to file a Petition for Rehearing out of time is denied.

3a

Filed Sept. 28, 1973

In the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Florida

Gainesville Division

Mary Alice Marshall, et al., Plaintiffs,

v.

Donald Holmes, et al., Defendants.

Gainesville Civil Action No. 508

OPINION-ORDER

STATEMENT OF THE ACTION

Plaintiffs in this class action attack the validity of

Florida Statutes, Section 40.01 relating to qualifications

and disqualifications of jurors. This statute1 is alleged

to offend the United States Constitution both on its face

and as applied. Plaintiffs are black and female citizens

who are making a three-pronged attack on the method

of selecting jurors in Levy County, Florida. They allege

that (1) the statute is unconstitutional in that it limits

1The portion of the statute assailed provides:

“(1) Grand and petit jurors shall be taken from the male and fe

male persons over the age of twenty-one (21) years, who are citi

zens of this state and who have resided in this state for one (1)

year and in their respective counties for six (6) months and who

are fully qualified electors of their respective counties; provided,

however, that expectant mothers and mothers with children under

eighteen (18) years of age, upon their request, shall be exempted

from grand and petit jury duty . . .” (Emphasis supplied)

This statute has been recently amended to lower the minimum age

of qualification of prospective jurors to 18 years of age and this

is not at issue in this cause.

4a

potential jurors to those registered jto vote, (2) that

blacks and women are underrepresented on jury lists,

and (3) that women are discriminated against since

women who have children under eighteen (18) years

of age may be exempt from jury service upon request.

There are also claims under certain provisions of the

Florida Constitution considered by this Court not worthy

of comment.

Jurisdiction is founded also on the provisions of Title

42, United States Code, Section 1981 and 1983 and

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281.

APPLICATION FOR THREE JUDGE COURT

Initially, this Court was confronted with the threshold

issue of determining the propriety of three-judge court

relief as demanded by plaintiffs and as contemplated by

Title 28, USCA, Sections 2281 and 2284. Specifically,

this Court had to decide whether the constitutional issue

presented in the amended complaint was “substantial”

thus requiring the empanelling of a statutory three-judge

tribunal. Mayhue’s Super Liquor Store, Inc. v. Meikle-

john, 426 F.2d 142, 144 (5th Cir. 1970).

If the constitutional issue is clearly lacking in merit

or judicially emasculated by prior Supreme Court pro

nouncements foreclosing the matter as a subject of con

troversy on constitutional grounds, then the existence

of a substantial federal question is deemed wanting.

Ex parte Poresky, 290 U.S. 30 (1934). Logically

then where the challenged statutory enactment with

stands the constitutional attack and is assailed in its mere

application by state authorities which action allegedly

yields an unconstitutional result, the prerequisites for

5a

convening a three-judge court have not been fulfilled.

Ex parte Branford, 310 U.S. 354, 361 (1939).

In the instant case plaintiffs question the statutory

standard limiting those people eligible to serve on Flori

da juries to those who are “fully qualified electors.” Ad

ditionally, plaintiffs contest the statutory provision allow

ing women who have children under eighteen (18)

years of age to be exempt from jury service upon request.

As a result, therefore, of the application of the Florida

statute plaintiffs contend that unconstitutional discrimi

nation against blacks and women obtain.

In Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, 396

U.S. 320 (1970), the Supreme Court of the United

States upheld the decision of a statutory three-judge

court, finding that an Alabama statute, similar to the

Florida statute challenged herein, was not “irredeemably

invalid on its face.” Ibid., at 332. In assessing the merits

of appellants’ argument the Supreme Court noted ap

provingly of other state laws using the same or similar

language to that contained in the Alabama statute. The

Court then concluded that although the Alabama statute

had been applied in such manner that blacks had been

discriminated against, the statutory language standing

alone passed constitutional muster and should not be

stricken down. Compare Franklin v. South Carolina,

218 U.S. 161 (1910).

Thus, it affirmatively appeared to this Court that the

constitutional question sought to be raised for determi

nation by a three-judge court was insubstantial and had

been foreclosed by previous decisions of the Supreme

Court. Ex Parte Poresky, supra. The application for

convening a three-judge court pursuant to Title 28,

6a

USCA, Section 2284 was denied in a written order of

this Court dated August 22, 1972.

It is, however, the view of this Court that the amended

complaint does contain allegations of deprivation suffi

cient to state a claim for declaratory and injunctive re

lief. Accordingly, the Court makes the following find

ings of fact and conclusions of law as may be required

by Rule 52, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

FINDINGS OF FACT

1. Plaintiffs are male and female black citizens of

Levy County, Florida. They are over the age of eighteen

(18) years, have resided in Florida for one year and

in the County for six months, and are fully qualified

electors for Levy County, Florida.

2. The current system of selecting jurors in Levy

County, instituted in August 1970, operates as follows:

(a) Questionnaires are mailed to all registered

electors in Levy County.

(b) From the questionnaire responses an “eligi

bility” list is developed; those individual electors

not qualifying for exemptions from jury duty and

those persons who failed to return the questionnaire

forms are placed on the eligibility list.

3. In August 1970, there were 4,966 registered elec

tors in Levy County, Florida, of which 4,415 were white

and 551 were black persons.

4. From the total of 4,966 registered electors, 2,978

names were placed in the eligibility file. Of this number

376 were black persons and 2,602 were white persons.

Of the 376 black persons, 172 were male and 204 female

7a

and of the 2,602 white persons, 1,434 were male and

1,168 were female.

5. From the total of 2,978 names in the eligibility

file, 625 names were selected on a random basis and

were placed in the juror wheel.

6. Since the initial composition of the eligibility list,

all newly registered electors are sent the questionnaire

form referred to above and depending upon the availa

bility to them of certain of the statutory exemptions,

their names are placed on the eligibility list.

7. During the years 1969-1972, black persons in

Levy County have consistently constituted approxi

mately 11.30% of the duly registered electors for that

county. The same statistics compiled by the Secretary

of State and furnished to the Court by the plaintiffs ( see

the Court’s Exhibit I attached herein), reflect that dur

ing the years 1969-1973, black persons constituted

12.81, 14.47, 7.64, 14.39 and 18.0% of those on jury

lists.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. This Court has jurisdiction over the subject matter

of and the parties to this action.

2. Plaintiffs contend herein that Florida Statutes, Sec

tion 40.01, upon which the Levy County, Florida juror

selection plan is predicated, is unconstitutional (1) in

that it limits potential jurors to those registered to vote;

(2) that blacks and women are underrepresented on

jury lists and (3) that women who have children under

eighteen (18) years of age are discriminated against

since they may be exempt from service upon request.

8a

3. In regard to plaintiffs’ claim that use of a “regis

tered elector” list to select jurors is an unconstitutional

limitation upon the right of every individual to serve

as a juror, this Court feels that the argument is badly

eroded, if not absolutely foreclosed, by the Supreme

Court pronouncements in Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443

at 474 (1952) and Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene

County, 396 U.S. 320 at 332 (1970).

Although the instant case is an attack by plaintiffs

seeking affirmative relief from alleged discriminatory

juror selection, Brown v. Allen, supra, is helpful even

though that case involved defendants challenging judg

ments of criminal convictions on the ground of syste

matic exclusion of Negroes from grand juries. In both

cases the parties have a “cognizable legal interest in non-

discriminatory jury selection.” Carter, supra, at 329.

Commenting on a system in Brown where property

and poll tax lists were used, Justice Reed noted that,

“Our duty to protect the federal constitutional

rights of all does not mean we must or should im

pose on states our conception of the proper source

of jury lists, so long as the source reasonably re

flects a cross section of the population suitable in

character and intelligence for that civic duty.”

Brown, supra, at 474.

Justice Stewart in the opinion of the Court in Carter v.

Jury Commission of Greene County, supra, adopted the

language of Justice Reed in validating the multi-list sys

tem in Greene County, Alabama.

It is, therefore, apparent to this Court that to the ex

tent plaintiffs contest the use of a “registered electors”

9a

list, their argument is without merit. Clearly, this list if

it reasonably reflects a cross section of the Levy County

population is permissible.

4. Plaintiffs’ second contention is that blacks and

women are underrepresented on Levy County juror

lists. The Court understands this argument to be that

whatever the listing system used in Levy County, it does

not reasonably reflect a cross section of the population

of Levy County. The plaintiffs are not contending that

they are entitled to a proportional representation by race

or by sex on any particular grand or petit jury since this

has been foreclosed on numerous occasions by the Su

preme Court and more recently rejected again in Carter,

supra.

In order to prevail it is incumbent upon plaintiffs to

show by substantial evidence that the Florida statute,

under which the Levy County plan was developed, op

erates to unfairly and unreasonably represent blacks and

women on juror lists. Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57, 69

(1961); Hernandez v. State of Texas, 347 U.S. 479

(1954); United States v. Pentado, 463 F.2d 355 (5th

Cir. 1972).

An examination of the record reveals no evidence of

such underrepresentation of either blacks or women. To

the contrary the evidence would suggest that the black

persons in Levy County in 1969, who represented

11.51% of the registered electors of Levy County, con

stituted 12.81% of individuals on juror lists. In 1971,

11.08% of the registered electors were black yet 14.39 %

of the individuals on juror lists were black. Figures for

the first two months of 1973, reflect that blacks consti

tute 18% of juror list names.

10a

To the suggestion that the comparison should be

made between the percentage of blacks in the Levy

County population and the percentage reflected on the

juror lists, the Court can only take some direction from

the statistics and findings in Carter v. Jury Commission

of Greene County, supra. Plaintiffs would show that

although approximately 25 % of the population in Levy

County is black, they constitute only about 15 % of juror

lists. However, the plight of appellants in Carter, supra,

was that while 75% of the Greene County population

was black, the largest number of blacks ever to appear

on the jury list between 1961 and 1963 was 7% of the

total. In 1966 only 4% of the blacks in Greene County

found their way to the jury roll. Yet neither the District

Court nor the Supreme Court enjoined the enforcement

of the challenged statute.

It, therefore, is the view of this Court as to plaintiffs’

second contention that plaintiffs have not carried the

legal burden of showing the discrimination which is

alleged. Clearly, there has been no showing that the

statute is incapable of being carried out with no dis

crimination as is required by Carter v. Jury Commission

of Greene County, supra. Accordingly, this Court finds

that the elector listing system which is the basis for the

Levy County juror lists and which is provided for in the

Florida Statutes, Section 40.01, reasonably and suffi

ciently reflects a cross section of the population of Levy

County, Florida.

5. As to plaintiffs’ contention that the statute is

unconstitutional because it allows women with children

under eighteen (18) years of age to be exempt from

jury duty upon their request, this Court finds the argu

ment to be devoid of merit.

11a

The right of women to serve on juries without dis

crimination is not an issue before this Court. The Court

is doubtful that such an issue would ever again be seri

ously raised in this day and time; certainly, the case law

explicitly recognizing the right of women to serve as

jurors is too numerous to mention. Even evidence in

the record of this case to which plaintiffs stipulate as

true, reflects for instance in the year 1972, that 48.29%

of those individuals on juror lists in Levy County were

women.

But the plaintiffs’ specific complaint is that the exemp

tion in Florida Statutes, Section 40.01(1) which is avail

able upon request is unconstitutional. This Court cannot

countenance such an argument. The “restraint” which

plaintiffs seem to suggest simply does not exist; the stat

ute just does not operate to prohibit any woman who

is a registered elector from serving on a jury in Levy

County. Rather, the normal operation of the statute

would place on women desiring the exemption, an affirm

ative duty of requesting it. If in practice it is somehow

discriminatory toward women, at least plaintiffs have

failed to carry the burden of showing such discrimina

tion. Hoyt v. Florida, supra.1

^ee Hoyt v. Florida, supra. In 1961 the Supreme Court construed

Florida Statutes 40.01(1). The Court upheld its validity even

absent the provisions giving women the affirmative duty of claim

ing the exemption which appears in its present amended form. The

Court noted that:

“The disproportion of women to men on the list indepen

dently carries no constitutional significance. In the adminis

tration of the jury laws proportional class representation is

not a constitutionally required factor.” Hoyt, supra, at 69.

While it is alleged that, though not explicitly overruled, Hoyt has

been “eroded,” see Healy v. Edwards,___ F. Supp. ____ , E.D.

Louisiana 1973 (Slip N o ._____ , August 31, 1973), 42 LW 1041,

12a

In sum, the Court finds that Florida Statutes, Section

40.01 is neither unconstitutional on its face nor as it is

applied in Levy County, Florida, and as this Court has

heretofore ruled, the issues raised in plaintiffs’ behalf

have been foreclosed by previous decisions of the Su

preme Court and thus a substantial federal question is

clearly wanting for purposes of convening a Three-Judge

Court. Ex parte Poresky, supra. It is, therefore,

ORDERED that judgment in this matter shall be

entered disposing of the issues raised in the pleadings

in favor of the defendants.

DONE and ORDERED in Tallahassee, Florida, this

28th day of September, 1973.

s /D avid L. M iddlebrooks

David L. M iddlebrooks

United States District Judge

by Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), the Court notes that Reed

involved a “statutory scheme which draws a sharp line between

the sexes solely for the purpose of achieving administrative con

venience.” Reed, supra, at 77. The present amended form of Flori

da Statutes 40.01(1) which is contested in the matter before this

Court involves no such statutory scheme solely for administrative

convenience. More importantly, however, the proposition in Hoyt

that plaintiffs must show the alleged discrimination by substantial

evidence, upon which this Court has relied, is unscarred.

13a

United States District Court

For the Northern District of Florida

Gainesville Division

Civil Action File No. GCA 508

Mary Alice Marshall, et al.

vs.

Donald Holmes, et al.

JUDGMENT

This action came on for hearing before the Court,

Honorable David L. Middlebrooks, United States Dis

trict Judge, presiding, and the issues having been duly

heard and a decision having been duly rendered,

It is Ordered and Adjudged

That the plaintiff take nothing, that the action be dis

missed on the merits, and that the defendants, Donald

Holmes et al, recover of the plaintiffs, Mary Alice Mar

shall et al, their costs of action.

Dated at Tallahassee, Florida, this 28th day of Sep

tember, 1973.

Filed Sept. 28, 1973.

M arvin S. W aits

Clerk of Court

F. F. T aylor

Deputy Clerk

14a

In the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Florida

Gainesville Division

Mary Alice Marshall, et al., Plaintiffs,

versus

Donald Holmes, et ah, Defendants.

Civil Action No. 508

STIPULATED FACTS

The parties agree that the following facts are true and

correct to the best of their knowledge and stipulate that

they shall with this Court’s consent be the operative facts

for this litigation.

1. The current system of picking names for the jury

list was instituted in Levy County in August, 1970.

2. A questionnaire was mailed to each registered elec

tor. Exhibit A to Motion for a Three Judge Court. An

eligibility file was developed by eliminating those persons

who in the judgment of the Defendants qualified for

statutory exemptions from jury duty. Those who did not

qualify for exemptions and those persons who did not

return their questionnaires were placed into an eligibility

file.

3. The total voter registration as of August 1970 was

4,966 of which 4,415 were white and 551 were black.

(A male-female breakdown of this figure was requested

Filed April 20, 1973.

15a

from the Supervisor of Elections but this information

was not kept by that office and is not available.)

4. The names of 376 black persons were placed in

the eligibility file of which 172 were male and 204 fe

male. There were 2,602 white persons’ names placed

in the eligibility file, 1,434 being male and 1,168 being

female.

5. From the total of 2,978 names, 625 names were

selected on a random basis from the eligibility file to be

placed in the box from which jurors’ names are drawn.

6. The figures in Exhibit I reflect the best and most

complete knowledge of the parties.

7. Subsequent to the initial composition of the list,

each newly registered elector has received a question

naire. Each elector who has died or moved that is made

known to the Defendants is eliminated from the file.

8. The cards which are placed in the file of those who

are eligible voters contain the following information:

the name, address, date, race, sex, and an indication of

which year(s) the person served as a juror.

9. According to the 1970 Census 25.2% of the popu

lation of Levy County was “Negro and other races.” The

Census indicated that only 11 of these persons were not

Negroes.

s/ K ent Spriggs,

for the Plaintiffs

s/ Arthur C. Can ad ay,

for the Defendants

EXHIBIT I

ELECTORS JURY LISTS ELIGIBILITY FILE

YEAR Wh Bla %B M F % F Wh Bla %B M F % F Wh Bla %B M F % F

1969** 4643 604 11.51 177 26 12.81 123 80 39.41

1970 130 22 14.47 114 38 25.0

Aug.

1970 4415 551 11.1 2602 376 12.62 1606 1372 46.07

1971** 4506 573 11.08 145 12 7.64 100 57 36.31

1972 5740 745 11.49 351 59 14.39 212 198 48.29

1973* 41 9 18.0 31 19 38.0

* Figures for 1973 available only thru February 27.

Statistics listed in row “August 1970” derived from Affidavit of W. F. Gavin, Chairman of the Levy

County Jury Commission; statistics under section headed “Jury Lists” derived from Levy County

Venire sheets; statistics listed under “Electors” for 1972 provided by Secretary of State; percentages

calculated by Plaintiffs’ counsel.

**Statistics listed under “Electors” for 1969 and 1971 provided by Secretary of State.

17a

In the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Florida

Gainesville Division

Mary Alice Marshall, et ah, Plaintiffs,

versus

Donald Holmes, et al., Defendants.

Civil Action No. 508

SUPPLEMENTAL STIPULATION

1. The total number of women claiming the Section

40.01 (1) exception for mothers and expectant mothers

in Question 17 is 623 as of April 23, 1973.

2. On that same date, the number of those 623 who

indicated in their answer to Question 4 that they had

outside employment was 195.

3. The year of birth of the youngest child indicated

in the answer to Question 17 was as follows:

1952 0

1953 6

1954 18

1955 23

1956 29

1957 19

1958 25

1959 28

Filed May 11, 1973.

18a

1960 33

1961 29

1962 27

1963 28

1964 32

1965 47

1966 35

1967 38

1968 48

1969 49

1970 48

1971 31

1972 11

1973 1

expectant mothers 12

s / K e n t Spr ig g s , ____________________

for the Plaintiffs, for the Defendants.

4/24/73

The above figures were compiled by Plaintiffs. While

Defendants have no personal knowledge of them, they

are willing to assume their accuracy for purposes of

this case.

s / A r t h u r C . C anaday ,

for the Defendants

5/9/73