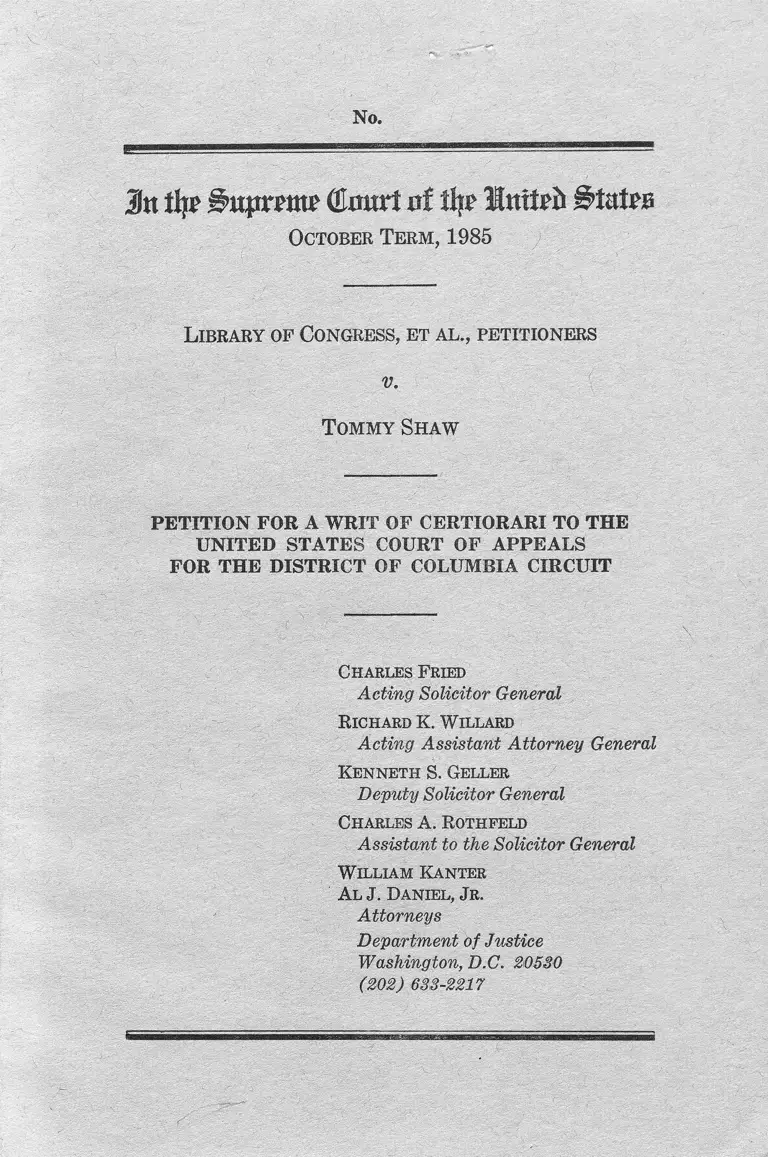

Library of Congress v. Shaw Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Library of Congress v. Shaw Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1985. 03fb0049-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c95397de-686e-428f-a8e9-4c5013bfebe0/library-of-congress-v-shaw-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

No,

In tfy Bnpnm (tairt nf % Intt^ ii’tata

October Term, 1985

Library of Congress, et al., petitioners

v.

Tommy Shaw

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Charles Fried

Acting Solicitor General

R ichard K. W illard

Acting Assistant Attorney General

Kenneth S. Geller

Deputy Solicitor General

Charles A. Rothfeld

Assistant to the Solicitor General

W illiam Kanter

A l J. Daniel, Jr.

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-2217

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether Section 706 (k) of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(k), which makes the United

States liable for attorneys’ fees “ the same as a private

person,” waives the federal government’s sovereign

immunity so as to permit the recovery o f interest on

attorneys’ fee awards against the United States.

( i )

II

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

In addition to the parties named in the caption,

petitioners include Daniel J. Boorstin, Librarian of

Congress; Donald C. Curran, Associate Librarian of

Congress; and John J. Kominsky, General Counsel,

Library of Congress.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinion below_____ _________________ _____ ____ ___ - 1

Jurisdiction ............... ........ ........ ....................................... 1

Statute involved ...... ........................................................ . 2

Statement..... ....... ......... ....................................................... 2

Reasons for granting the petition.... ....... ....................... 6

Conclusion ________________________ ________________ 17

Appendix A ..... ................... ................. ........ ..................... la

Appendix B ......... 57a

Appendix C _______________ _____________________ ___ 70a

Appendix D .... ..... 71a

Appendix E ......... 73a

Appendix F ....... .............. .......... ................................... . 74a

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Albrecht V. United States, 32:9 U.S. 599................ 9,14

Arvin v. United States, 742 F.2d 1301 ................... 12, 16

Blake V. Calif ano, 626 F.2d 891 ........................8, 10, 12,15

Boston Sand Co. V. United States, 278 U.S. 41....... 10,11

Canadian Aviator, Ltd. V. United States, 324 U.S.

215_____________ 11

Christiansburg Garment Co. V. EEOC, 434 U.S.

412............... ........... .............................................. . 12

Copeland V. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880........................ 3,17

Copper Liquor, Inc. V. Adolph Coors Co., 701 F.2d

542 ......................... ........ ................... ................. . 14

Cross V. United States Postal Service, 733 F.2d

1327, aff’d, 733 F.2d 1332, cert, denied, No. 84-

979 (Mar. 18, 1985) .................................. .......... 15

deWeever V. United States, 618 F.2d 685 ............... 15

Fischer V. Adams, 572 F.2d 406 ................... .......... 15

General Motors Corp. V. Devex Corp., 461 U.S. 648.. 13

Page

(III )

Cases— Continued:

IV

Page

Holly V. Chasen, 639 F.2d 795, cert, denied, 454

U.S. 822 ____ ________ ____ ______ ___________9, 10, 12

Indian Towing Co. V. United States, 350 U.S. 61.. 11

Knights of the Ku Klux Klan V. East Baton Rouge

Parish School Board, 735 F.2d 895 ................ ..14-15, 16

Lehman V. Nakshian, 453 U.S. 156...................8 , 10, 13-14

Marziliano V. Heckler, 728 F.2d 151 ______ _____ 15

McMahon V. United States, 342 U.S. 25 ___ __ ___ 7, 8

Murray V. Weinberger, 741 F.2d 1423........ .......... . 6

Perkins V. Standard Oil Co. of California, 487 F.2d

672 .............................. ...................... ..................... 14

Richerson V. Jones, 551 F.2d 918 ____ ___ ______

Rodgers V. United States, 332 U.S. 371 ___________ 13

Ruckelshaus V. Sierra Club, 463 U.S. 680 ............. . 8, 14

Saunders V. Claytor, 629 F.2d 596, cert, denied,

450 U.S. 980 .............. ........ ................................... 15

Segar V. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249, cert, denied, No. 84-

1200 (May 20, 1985) ____________________ ____ 12, 15

Smyth V. United States, 302 U.S. 329 ___________ 9

Soriano V. United States, 352 U.S. 270 _________ 8

Standard Oil Co. V. United States, 267 U.S. 76__ 11

Tillson V. United States, 100 U.S. 43 ____ __ ______ 11

United States v. Alcea Band of Tillamooks, 341

U.S. 48 ________ __ _______________ ___ _______ 8, 9,11

United States v. Goltra, 312 U.S. 203__ ___ ____9, 10,11

United States V. King, 395 U.S. 1 __________ ___ 10

United States V. Louisiana, 446 U.S. 253..... ........ . 9, 10

United States V. Mescalero Apache Tribe, 518 F.2d

1309, cert, denied, 425 U.S. 911_______________ 8

United States V. North American Transp. & Trad

ing Co., 253 U.S. 330 .... ............ ......... ................. 8, 10

United States V. North Carolina, 136 U.S. 211__ 10

United States v. N.Y. Rayon Importing Co., 329

U.S. 654................... ....... ................................. ..... 9,10

United States V. Sherman, 98 U.S. 565 ............ ...... 10

United States V. Sherwood, 312 U.S. 584_____ _ 8

United States V. Testan, 424 U.S. 392 ___________ 8

United States V. Thayer-West Point Hotel Co., 329

U.S, 585.......... ............... ..... ........ ................ ....... . 9,10

United States V. Verdier, 164 U.S. 213___________ 10

United States V. Worley, 281 U.S. 339 ........ ...... ..9-10, 11

United States V. Yellow Cab Co., 340 U.S. 543.... . 11

United States ex rel. Angarica V. Bayard, 127 U.S.

251 ........................................................................... 9

Statutes:

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352,

§ 706 (k), 78 Stat. 261............................. ........... ., 12

Equal Access to Justice Act, Pub. L. No. 96-481,

94 Stat. 2325 et seq.:

§ 203 (c ) , 94 Stat. 2327 ................................. 14

§ 204 (c ) , 94 Stat. 2329 ............. ........ ............ . 14

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub.

L. No. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103, 42 U.S.C. 2000e

et seq......... ........................................... —......... ...... 12

42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 (k) ...... ..1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 12, 13,14,16

War Risk Insurance Act of 1914, ch. 293, 38 Stat.

711 et seq. .......... .......... .......................................... 11

5 U.S.C. 504.................... ............ ................................ 14

15 U.S.C. 15......... ......... ................ ....... - ......... ......... 14

26 U.S.C. 7426 ( g ) ............ .......................................... 13

28 U.S.C. 1961(c) (2 )____________________ _______ 13

28 U.S.C. 2411..... .......................... .............. .............. 13

28 U.S.C. 2412 ......... ................ .................................. 15

28 U.S.C. 2412(b) ...... .... ..... ............................. 14,15

28 U.S.C. 2412(d)....................... ............................... 14

28 U.S.C. 2412(d) (1) (A) ................... ................. . 15

28 U.S.C. 2516(a) ..................................... ............... . 10,13

28 U.S.C. 2516(b)________________ _____________ 13

29 U.S.C. 683a _______ _____ __ ______________ ___ 14

31 U.S.C. 1304(b) (1) ( A ) ____________ __________ 13

31 U.S.C. 1304(b) (1) (B) .................. ................... 13

31 U.S.C. 3728(c) ...... ..................... .............. ........... 13

40 U.S.C. 258a ................. ............... ....... .... ..... ........ 13

Miscellaneous:

H.R. 2378, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. (1985).................... 15

H.R. Rep. 92-899, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. (1972)........... 12

H.R. Rep. 92-238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971)..... 12

H.R. Rep. 99-120, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. (1985)........ 15

S>. Rep. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) __ 12

S. Rep. 92-681, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. (1972)................ 12

V

Cases—Continued: Page

3n % G J m t r t at % I n i t ^ § t a t e

October Term, 1985

No.

Library of Congress, et al., petitioners

v.

Tommy Shaw

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

The Solicitor General, on behalf of the Library of

Congress, et ah, petitions for a writ of certiorari to

review the judgment of the United States Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in this

case.

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (App., infra,

la-56a) is reported at 747 F.2d 1469. The opinion

and judgment of the district court (App., infra, 57a-

70a) are unreported.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals (App., infra,

71a-72a) was entered on November 6, 1984; an order

denying rehearing (App., infra, 73a-75a) was en

(1)

2

tered on February 20, 1985. On May 8, 1985, the

Chief Justice extended the time within which to file

a petition for a writ of certiorari to June 27, 1985.

On June 21, 1985, the Chief Justice further extended

the time for filing the petition to July 12, 1985. The

jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

1254(1).

STATUTE INVOLVED

42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(k) provides:

In any action or proceeding under this sub-

chapter the court, in its discretion, may allow the

prevailing party, other than the [Equal Employ

ment Opportunity] Commission or the United

States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the

costs, and the Commission and the United States

shall be liable for costs the same as a private

person.

STATEMENT

1. In 1976 and 1977 respondent filed administra

tive complaints charging his employer, the Library of

Congress (Library), with racial discrimination.

These complaints were settled in August 1978, when

the Library agreed to award respondent back pay

and to take certain other remedial measures. App.,

infra, 2ar3a. Shortly afterwards, however, after con

sultation with the Comptroller General, the Library

informed respondent that it lacked the authority to

provide such relief absent a specific finding of racial

discrimination (App., infra, 3a & n.7). Respondent

then brought suit, arguing that Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended by the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Act of 1972 (Title V II), 42

U.S.C. 2000e et seq., authorized the Library to afford

the relief specified in the settlement agreement (App.,

infra, 3a-4a).

3

On September 14, 1979, the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia ruled in respond

ent’s favor on the merits (see App., infra, 4a). The

court accordingly held (see ibid.) that respondent’s

attorney 1 was entitled to an award of fees under the

Title VII attorneys’ fees provision, which states

that “ the court, in its discretion, may allow the pre

vailing party * * * a reasonable attorney’s fee as

part of the costs, and * * * the United States shall

be liable for costs the same as a private person.” 42

U.S.C. 2000e-5(k). But the district court declined to

set the fee award pending a decision by the en banc

District of Columbia Circuit in Copeland v. Marshall,

641 F.2d 880 (1980), which the district court antici

pated would provide guidance on the standards ap

plicable in the computation of attorneys’ fees. See

App., infra, 4a, 60a. The court of appeals’ decision

in Copeland ultimately issued almost one year later,

on September 2, 1980.

Over one additional year passed before the district

court, on November 4, 1981, issued an order setting

fees and awarding them to respondent’s attorney. The

court began by fixing the so-called “ lodestar” (see

App., infra, 2a n.2) based on the number of hours

worked and the attorney’s 1978 hourly rate (id. at

5a, 62a-66a). After making a variety of adjustments

to the lodestar that are not relevant here (see id. at

5a, 66a-68a), the district court declared that “ [t]his

1 The attorney whose fee is at issue here, Shalon Ralph,

represented respondent in 1978, while the case was in its

administrative phase; he also provided some assistance dur

ing the district court proceedings (App., infra, 4a, n.13). The

fee claims of respondent’s other counsel have been settled

(ibid.). References to “ respondent’s attorney” in this peti

tion therefore are directed only at Ralph.

4

case should have ended in August 1978, or at the

latest in November of that year. I f [respondent’s

attorney] had been compensated at about that time,

he could have invested the money at an average yield

of not less than 10% per year. It is the fault of

neither [respondent] nor [his attorney] that payment

was not made sooner.” Id. at 68a (footnote omitted).

Because three years had passed since late 1978, the

court accordingly ordered “an upward adjustment

[of the fee] of 30% for delay” (ibid.).

2. On appeal, a divided panel of the court of ap

peals rejected the Library’s contention that the 30%

delay adjustment was improper because Congress in

Section 2000e-5(k) had not authorized the award of

interest against the United States. The panel ma

jority acknowledged that the delay adjustment was

interest because it “was designed to reimburse [re

spondent’s] counsel for the decrease in value of his

uncollected legal fee between the date on which he

concluded his legal services and the court’s estimated

date of likely actual receipt” (App., infra, 11a (foot

note om itted); see id. at 12a-13a & n.41). And the

court acknowledged the force of the so-called “no

interest rule”— that the United States may not be

held liable for interest in the absence of an express

waiver of its sovereign immunity (id. at 13a).

The court of appeals held, however, that Section

2000e-5(k) is such a waiver. The court noted that

private parties generally may be held liable for in

terest on fee awards under Title VII, and that Title

VII makes the United States liable for costs “ The

same as a private person.’ ” . This, the court concluded,

is an “express” statutory waiver as to interest, the

range of which “ is defined in unmistakable language.”

App., infra, 15a. The court also based its holding on

5

an alternative ground: that “ the traditional rigor of

the sovereign-immunity doctrine [is relaxed] when a

statute measures the liability of the United States by

that of private persons” (id. at 24a).2

Judge Ginsburg dissented. She agreed that the

30% adjustment is interest, but concluded that noth

ing in either Section 2000e-5(k) or its legislative

history so much as adverts to an intent to overcome

the “no-interest rule” (App., infra, 41a). Judge

Ginsburg also noted that sovereign immunity prevents

Title VII 'plaintiffs from recovering interest on back

pay awards entered against the government, and

found it unlikely that Congress would have given

Title VII attorneys more favorable treatment than

2 Although the court of appeals thus held that attorneys

may be awarded interest under Section 2000e-5(k), it none

theless remanded the case to the district court for further

proceedings. In the majority’s view, “a delay-in-payment ad

justment [is] appropriate only where the lodestar is the per-

hour charge to clients who pay when billed” (App., infra, 8a

n.28). The court suggested, however, that a lodestar may

“ represent [] a higher rate charged clients who sue under

fee-shifting statutes,” in which case the figure might already

“ha[ve] taken into account the pecuniary disadvantage re

sulting from the lengthy wait far payment ordinarily en

countered under such statutes” (ibid.). In such circum

stances, the panel concluded, “ an upward adjustment for

delay would * * * result in the attorney being paid twice for

the delay” (ibid.). The court of appeals therefore instructed

the district court, on remand, to determine whether the lode

star had been based on a rate that “has already taken into ac

count the pecuniary disadvantage resulting from the lengthy

wait for payment” (id. at 37a). If so, the district court was

to vacate its 30% delay adjustment (ibid.). The court of ap

peals also noted that, following oral argument in the case, it

had ordered the government to pay the undisputed portion of

the attorney’s fee (App., infra, 6a n.24) ; that payment has

since been made.

6

their clients (id. at 42a-44a). She therefore concluded

that Congress could not “ ‘plainly’ [have] resolved an

immunity waiver issue never even framed in the

course of its deliberations” (id. at 41a).3

The Library’s petition for rehearing en banc was

denied, with Judges Ginsburg, Bork, Scalia, and

Starr dissenting (App., infra, 73a-75a).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION

The decision below announces an expansive refor

mulation of the sovereign immunity doctrine. For

more than a century, this Court consistently has held

that federal statutes should not be deemed to allow

interest to run on a recovery against the United

States unless Congress affirmatively desired that re

3 Although Judge Ginsburg thus found no justification in

the statute for an award of interest against the United States,

she suggested that, under Murray V. Weinberger, 741 F.2d

1423 (D.C. Cir. 1984), there is a meaningful distinction be

tween “ interest” and an “ adjustment for delay in receipt of

payment” (App., infra, 38a). She explained: “ [j]ust as an

attorney setting an hourly rate in a contingent fee case may

factor in the risk that the cause may not prevail, so too an

attorney embarking on services for which he or she antici

pates payment ultimately, but not promptly, may factor in

the expected delay” (id. at 38a-39a). Judge Ginsburg there

fore would require a district court to determine whether an

attorney’s historic rates (those that he charged at the time

that he did the work at issue) were enhanced by such a delay

factor. If so, the attorney would be entitled to reimbursement

at that enhanced rate—but not to any additional recovery

because of actual delay in receiving fees. If the historic rate

did not contain a component for anticipated delay in the ret-

ceipt of fees, however, Judge Ginsburg in an “ appropriate”

case would permit the district court to use current market

rates rather than historic rates in computing the lodestar, if

doing so would not generate a windfall for the attorney. Id.

at 50a-53a.

7

suit and announced its intentions in unambiguous

terms. The court of appeals’ contrary conclusion—

that 42 U.S.C. 2000e5(k) effected a waiver of sover

eign immunity as to interest despite the absence of

anything in the statute or its legislative history in

dicating an affirmative intention on the part of Con

gress to do so 4— cannot be reconciled with these

decisions.

By departing from the settled law in this area, the

District of Columbia Circuit has precipitated a con

flict in principle with the decisions of two other

courts of appeals, which have held that language in

a statute virtually identical to Section 2000e-5(k)

does not make the government liable for interest on

attorneys’ fees. Perhaps more important, it has

opened the federal treasury to a potentially wide

range of monetary awards that were unanticipated,

and not consciously authorized, by Congress, And

it has effectively substituted the judgment of the

courts for that of Congress in determining when the

federal government’s sovereign immunity is appro

priately deemed waived. In these circumstances, re

view of the decision belowT by this Court is warranted.

1. It is common ground that an award of interest

against the United States is permissible only if Con

gress has waived the government’s sovereign immu

nity as to such an award. In determining whether

Congress has done so, this Court has indicated that

analysis should begin with the principle that

“ [wjaivers of immunity must be ‘construed strictly

in favor of the sovereign,’ McMahon v. United States,

4 The case before the court of appeals involved only pre-

judgment interest. As Judge Ginsburg noted (App., infra,

44a-45a n.5), however, the logic of the court of appeals’ hold

ing applies to post- as well as prejudgment interest.

8

342 U.S, 25, 27 (1951), and not ‘enlarge[d] * * *

beyond what the language requires/ Eastern Transp.

Co. v. United States, 272 U.S, 675, 686 (1927).”

Ruckelshaus v. Sierra Club, 463 U.S. 680, 685-686

(1983) .5 And, as the court below acknowledged (App.,

infra, 13a), even when Congress has expressly per

mitted collection on substantive claims against the

United States, the “ ‘traditional rule’ [is] that interest

on [such] claims cannot * * * be recovered” unless

the awarding of interest was affirmatively and sepa

rately contemplated by Congress. United States v.

Alcea Band of Tillamooks, 341 U.S. 48, 49 (1951).

The court of appeals found that Section 2000e-5(k)

evidences such congressional intent— despite the omis

sion from the statute of any reference to interest (see

App., infra, 17a n.49)—-because private employers

may be held liable for interest on attorneys’ fees un

der Title VII, and the statute generally measures the

liability of the United States against that of private

defendants (App., infra, 14a-16a,).6 The court of ap

peals’ approach, however, cannot be reconciled with

the analysis that this Court consistently has applied

5 Accord Lehman v. NaJcshian, 453 U.S, 156, 161 (1981) ;

United States v. Testan, 424 U.S. 392, 400-401 (1976) ; Sori

ano V. United States, 352 U.S. 270, 276 (1957) ; United

States V. Sherwood, 312 U.S. 584, 586-587, 590 (1941).

6 Although respondent argued to the contrary in the court

of appeals (see App., infra, 10a), both the majority and the

dissenting opinions correctly concluded that the 30% upward

adjustment—which explicitly wasi intended to compensate re

spondent’s attorney for delay in the receipt of payment (see

id. at lla-12a)—was “ interest.” See United States v. North

American Transp. & Trading Co., 253 U.S. 330, 338 (1920) ;

Blake V. Califano, 626 F.2d 891, 895 (D.C. Cir. 1980) ; United

States V. Mescalero Apache Tribe, 518 F.2d 1309, 1322 (Ct.

Cl. 1975), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 911 (1976).

9

in resolving claims for interest against the federal

government.

a. Some 100 years ago, the Court was relying on

what already was a “well-settled principle, that the

United States are not liable to pay interest on claims

against them, in the absence of express statutory pro

vision to that effect.” United States ex rel, Angarica

v. Bayard, 127 U.S. 251, 260 (1888). Since that

time, the Court repeatedly has reaffirmed the notion

that, “ [a]part from constitutional requirements, in

the absence of specific provision by contract or stat

ute, or ‘express consent * * * by Congress,’ interest

does not run on a claim against the United States.”

United States v. Louisiana, 446 U.S. 253, 264-265

(1980), quoting Smyth v. United States, 302 U.S.

329, 353 (1937).7 Thus, a waiver of immunity is

effective only “where interest is given expressly by an

act of Congress, either by the name of interest or by

that of damages.” Bayard, 127 U.S. at 260. “ The

waiver cannot be by implication or by use of am

biguous language” (Holly v. Ckasen, 639 F.2d 795,

797 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 822 (1 9 8 1 ));

the “ consent necessary to waive the traditional im

munity must be express, and it must be strictly con

strued.” United States v. N.Y. Rayon Importing Co.,

329 U.S. 654, 659 (1947). Accord Tillamooks, 341

U.S. at 49; Albrecht v. United States, 329 U.S. 599,

605 (1947); United States v. Thayer-West Point

Hotel Go., 329 U.S. 585, 590 (1947); United States v.

Goltra, 312 U.S. 203, 207 (1941); United States v.

7 The “ constitutional requirements” arise in takings under

the Just Compensation Clause; the Court has held that just

compensation must include a payment for interest. See, e.g.,

Tillamooks, 341 U.S. at 49 ; Albrecht v. United States, 329

U.S, 599, 605 (1947) ; Smyth, 302 U.S. at 353-354.

10

Worley, 281 U.S. 339, 341 (1930); Boston Sand Co.

v. United States, 278 U.S. 41, 46 (1928); United

States v. North American Trans. & Trading Co., 253

U.S. 330, 336 (1920); United States v. North Caro

lina, 136 U.S. 211, 216 (1890); United States v.

Sherman, 98 U.S. 565, 567-568 (1878).s

In applying these principles, the courts have held

virtually without exception that the government’s im

munity can be found to have been waived in this con

text only when Congress affirmatively considered the

interest question and unambiguously affirmed its in

tention that interest should be available. See Holly,

639 F.2d at 797. Cf. Lehman v. Nakshian, 453 U.S.

156, 168 (1981); United States v. King, 395 U.S. 1,

4 (1969). This and other courts therefore have held,

for example, that interest could not be awarded when

the United States was required to disgorge funds

under an agreement that had permitted it to collect

and use revenues from disputed lands pending a de

termination of ownership ( United States v. Louisi

ana, 446 U.S. at 261-264), or when, “ in the adjust

ment of mutual claims” with a private party, the

United States was awarded interest on its claims.

North American Trans. & Trading Co., 253 U.S. at

336; United States v. Verdier, 164 U.S. 213, 218-219

(1896). 8

8 Several of these cases involved the construction of prede

cessors to 28 U.S.C. 2516(a), which permits an award of in

terest on judgments against the United States' in the Claims

Court “ only under a contract oir Act of Congress expressly

providing for payment thereof.” The Court repeatedly has

emphasized, however, that the statute simply “ codifies the

traditional rule” (N.Y. Rayon, 329 U.S. at 658) that the gov

ernment is immune “from the burden of interest unless it is

specifically agreed upon by contract or imposed by legisla

tion.” Goltra, 312 U.S. at 207 (footnote omitted). See

Thayer, 329 U.S. at 588; Blake, 626 F.2d at 894 n.6.

1 1

Interest also has been ruled unavailable under

statutes or contracts directing' the United States to

pay the “ ‘amount equitably due’ ” ( Tillson v. United

States, 100 U.S. 43, 46 (1879)), or “ any * * * equita

ble relief * * * the court deems appropriate” (Blake

v. Calif anno, 626 F.2d 891, 893 (D.C. Cir. 1980)), or

“ just compensation” (e.g., TUlamooks, 341 U.S. at

49; Goltra, 312 U.S. at 207-211)— even though “ just

compensation” for constitutional purposes has long

been understood to require payment of interest (see

note 7, supra). Indeed, the Court has indicated that

even statutory language basing federal liability

“ ‘upon the same principle and measure * * * as in

like cases * * * between private parties’ ” generally

“ hal[si] been understood * * * not to carry interest.”

Boston Sand, 278 U.S. at 46, 47.® 9

9 There is thus no merit to the court of appeals’ suggestion

that the traditional “no-interest rule” is inapplicable when

the statute at issue “ measures the liability of the United

States by that of private persons” (App., infra, 24a-36a).

Most of the decisions cited by the court of appeals on this

pointpS stand only for the unexceptionable proposition that

courts should not frustrate “ deliberate” waivers of sovereign

immunity. Canadian Aviator, Ltd. V. United States, 324 U.S.

215, 222 (1945) (cited at App., infra, 29a) ; see, e.g., Indian

Towing Co. V. United States, 350 U.S. 61, 69 (1955) (cited

at App., infra, 27a) ; United States V. Yellow Cab Co., 340

U.S. 543, 548 (1951) (cited at App., infra, 28a). Nor does

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 267 U.S. 76 (1925) (cited

at App., infra, 33a-34a) provide support for the court of

appeals’ conclusion. That decision held the United States li

able for interest on insurance policies issued under the War

Risk Insurance Act of 1914, ch. 293, 38 Stat. 711 et seq., only

because that insurance program was a for-profit venture

making use of standard commercial insurance contracts. See

United States v. Worley, 281 U.S. 339, 342 (1930). The

Court has declined to apply Standard Oil outside of its spe

cific commercial and contractual context. Worley, 281 U.S.

at 343-344.

12

b. The approach used by the court below in its

analysis o f Section 2000e-5(k) cannot be squared

with this settled law. That statute, of course, makes

no reference to interest, express or otherwise. And

as Judge Ginsburg observed, an examination of its

legislative history indicates that the interest issue

“ never even [was] framed in the course of [Con

gress’s] deliberations” (App., infra, 41a), let alone

addressed and resolved. Cf. Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d

1249, 1296 (D.C. Cir. 1984), cert, denied, No, 84-

1200 (May 20, 1985); Blake, 626 F.2d at 894|.10

Section 2000e-5(k) thus stands in sharp contrast

to the other statutes in which Congress has permitted

interest to run on substantive recoveries against the

United States. Those provisions in terms provide for

awards of interest, and spell out the “procedures

which a plaintiff must follow to perfect his entitle

ment to interest, the rate of interest which the United

States will pay on each type of judgment, and the

time when interest will start to run and the time it

will stop.” Arvin v. United States, 742 F.2d 1301,

1303 (11th Cir. 1984). See Holly, 639 F.2d at 797-

10 Section 2000e45 (k) was enacted in its current form as

Section 706 (k) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub.L.

No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 261. The legislative history of the

provision is “sparse” (Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC,

434 U.S. 412, 420 (1978)), and so far as we have been able

to determine it contains not a single reference to the avail

ability of interest. Similarly, we have been unable to un

cover anything bearing on the interest question in the legis

lative history o f the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, Pub.L. No. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq.,

which made Title VII applicable to federal employees. See

generally H.R. Rep. 92-899, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. (1972) ; S. Rep.

92-681, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. (1972) ; H.R. Rep. 92-238, 92d

Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ; S. Rep. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess.

(1971).

13

798.11 There is no reason to believe that Congress—

which was, of course, legislating against the back

ground of the “ no-interest rule”— intended Section

2000e-5(k) to signal a strikingly backhanded and

understated “ depart [lire] from its usual practice in

this area.” Nakshian, 453 U.S. at 162.12 See id. at

11 See 26 U.S.C. 7426(g) (providing-for interest in cases

of wrongful levy by the Internal Kevenue Service running

from the date of the levy) ; 28 U.S.C. 1961(c) (2) (providing

for interest on final judgments of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Federal Circuit in claims' against the United

States) ; 28 U.S.C. 2411 (providing for interest on overpay

ments of federal tax running from the date of overpayment) ;

31 U.S.C. 1304(b) (1) (A) (appropriating funds for interest

on certain district court judgments after an, unsuccessful ap

peal by the United States “ and then only from, the date of

filing of the transcript of the judgment with the Comp

troller General through the day before the date of the man

date of affirmance” ) ; 31 U.S.C. 1304(b)(1)(B ) (appropri

ating funds in similar circumstances, foir interest on decisions

of the Federal Circuit and the Claims Court; after affirmance

by the Supreme Court (see 28 U.S.C. 2516(b)). Cf. 31

U.S.C. 3728(c) (providing for the payment of interest on

debts wrongfully withheld by the Comptroller General in cer

tain set-off situations) ; 40 U.S.C. 258a (providing for the

payment of interest as part, of the compensation in proceed

ings for the taking of property by the United States). Con

gress also has. provided that “ [i] nterest on a claim against

the United States shall be allowed in a judgment of the United

States Claims Court only under a contract or Act of Congress

expressly providing for payment thereof.” 28 U.S.C. 2516(a).

12 This is particularly true where, as here, it is claimed

that Congress implicitly allowed an award of prejudgment

interest. In the absence of exceptional circumstances or a

statutory provision to the contrary, the usual rule is that such

interest may be awarded only from the date on which the

damages were liquidated oir readily calculable. See generally

General Motors Corp. V. Devex Corp., 461 U.S. 648, 651-652

& n.5 (1983), and cases cited; Rodgers v. United States, 332

U.S. 371, 373 (1947). Cf. Perkins V. Standard Oil Co. of Cali

14

161, 168-169 (holding trial by jury impermissible

in suits against the United States under the Age Dis

crimination in Employment Act (A D E A ), 29 U.S.C.

633a, because Congress “has almost always condi

tioned [waiver of sovereign immunity] upon a plain

tiff’s relinquishing any claim to a jury trial” and has

not “ affirmatively and unambiguously” provided that

right in the A D E A ). Cf. Sierra Club, 463 U.S. at

685 (when Congress is asserted to have departed

from traditional fee shifting rules “ a clear showing

that this result was intended is required” (footnote

om itted)). Indeed, two courts of appeals have relied

on precisely these considerations in holding that

awards of interest against the United States are not

authorized by the atorneys’ fee provision of the Equal

Access to Justice Act (28 U.S.C. 2412(b) (making

the United States liable for fees “ to the same extent

that any other party would be liable under the

common law or under the terms of any statute which

specifically provides for such an award” ) ) , which in

relevant part is virtually identical to Section 2000e-

5 (k ).13 Arvin, 742 F.2d at 1304; Knights of the

fornia, 487 F.2d 672, 675 (9th Cir. 1973) (under 15 U.S.C.

15, “ claims for ‘reasonable’ attorneys’ fees, being- unliqui

dated until they are determined by a court, are not entitled

to pre-judgment interest as would be certain liquidated

claims” ) ; Copper Liquor, Inc. v. Adolph Coors Co., 701 F.2d

542, 544 & n.3 (5th Cir. 1983) (affirming an award; of inter

est on attorneys’ fees under 15 U.S.C. 15 only from the time

of the “ judgment recognizing the right to costs and fees” ).

Had Congress intended to depart from that traditional rule,

it presumably “would have used explicit language to [that]

effect.” Sierra Club, 463 U.S. at 685 n.7.

13 Other provisions of the Equal Access to Justice Act au

thorizing fee awards against the United States when the gov

ernment’s position in litigation was not substantially justi

fied, 5 U.S.C. 504 and 28 U.S.C. 2412(d), expired on October

1, 1984. Sections 203(c) and 204(c), Pub. L. No. 96-481, 94

Stat. 2327, 2329. Congress is currently considering a bill that

15

Ku Klux Klan v. East Baton Rouge Parish School

Board, 735 F.2d895, 902 (5th Cir. 1984).14

Title VII itself, in fact, contains considerable evi

dence that the congressional scheme was not intended

to permit attorneys to obtain interest on their fees

in cases against the United States. While Title VII

plaintiffs may be awarded interest on back pay

awards against private employers (see, e.g., Blake,

626 F.2d at 893 & n.3 and cases cited), it is settled

law that interest does not run on back pay recovered

from the United States. Segar, 738 F.2d at 1296;

Saunders v. Clay tor, 629 F.2d 596, 598 (9th Cir.

1980), cert, denied, 450 U.S. 980 (1981); Blake, 626

F.2d at 984; deWeever v. United States, 618 F.2d

685, 686 (10th Cir. 1980); Fischer v. Adams, 572

F.2d 406, 411 (1st Cir. 1978); Richerson v. Jones,

551 F.2d 918, 925 (3d Cir. 1977); Cross v. United

States Postal Service, 733 F.2d 1327, 1329} affirmed

by an equally divided en banc court, 733 F.2d 1332

(8th Cir. 1984), cert, denied, No. 84-979 (Mar. 18,

1985). Had Congress given any attention to the in

terest question— and an award of interest could have

been affirmatively authorized only if Congress did so

—-it is difficult to imagine that, in a single legislative

would reenact these provisions, however. H.R. 2378, 99th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1985). See H.R. Rep. 99-120, 99th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1985). Significantly, this bill would add an explicit pro

vision to 28 U.S.C. 2412 allowing for interest on fee awards,

but only if the government challenges the award of fees on

appeal and loses. H.R. 2378, supra, § 2 (e).

14 The Second Circuit has affirmed a district court j udg-

ment that included an award of interest against the Departs

ment of Health and Human Services under 28 U.S.C. 2412

(b ) ’s companion provision, 28 U.S.C. 2412(d )(1 )(A ) (see

note 13, supra) , but it did so without discussion. Marziliano

v. Heckler, 728 F.2d 151, 155, 159 (2d Cir. 1984). See East

Baton Rouge, 735 F.2d at 902 n.8.

16

package, it would have chosen to accord plaintiffs’

lawyers more favorable treatment than that accorded

plaintiffs themselves.

2. The court of appeals’ novel approach to sover

eign immunity will have significant and, in many

cases, unpredictable effects. Its direct impact in the

Title VII area alone will be substantial: the General

Accounting Office informs us that, in fiscal year 1984,

the United States made payments to plaintiffs in over

150 Title VII suits (in almost all of which, presum

ably, liability for attorneys’ fees attached). And the

availability of prejudgment interest can be expected

to affect not only the dollar amount of the fee awards

in such cases (which the General Accounting Office

informs us totals several million dollars annually)

but also the conduct of a substantial body of em

ployment litigation.

The court of appeals’ analysis, in any event, is

plainly applicable in areas beyond Title VII. That it

leads to departures from this Court’s precedents and

the conclusions of other circuits already is evident:

as Judge Ginsburg noted, the panel majority’s' treat

ment of Section 2000e-5(k) has “preeipitat[ed] an

apparent circuit split” (App., infra, 56a n.14) with

decisions holding that the virtually identical fees pro

vision of the Equal Access to Justice Act does not au

thorize interest awards. Arvin, 742 F.2d at 1304;

East Baton Rouge, 735 F.2d at 902.15 The analysis

used below thus threatens one of the principal pur

poses served by the requirement that Congress ex

pressly waive the “no-interest rule”— the protection

of the treasury from unexpected liabilities arising at

unanticipated times. This danger is particularly

15 The panel majority itself noted that the attorneys’ fees

provision of the Equal Access to Justice Act is “ strikingly

similar” to Section 2000e-5(k), and seemingly disapproved

the holding in Arvin (App., infra, 29a-30a & n.107).

17

noticeable where, as here, an award of prejudgment

interest is concerned, for such liability may be found

to have attached years after the fact for reasons that

were wholly beyond the government’s control. In this

case, for example, the district court withheld assess

ment of an attorneys’ fee for one year pending the

decision in Copeland and for a second year while

the fee issue was under submission, and then ordered

the government to pay interest on a fee generated

three years earlier. See page 3, supra.

Most basically, the court of appeals’ conclusion that

courts may infer waivers of immunity from ambig

uous statutory language infringes in a direct way on

the congressional prerogative to waive the govern

ment’s sovereign immunity. For over 100 years,

Congress has been legislating against the background

of— and presumably relying upon— the “no-interest

rule” that consistently has been propounded by this

Court. If congressional legislation is to be inter

preted in light of a new controlling principle, it is

for this Court to make that judgment.

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be

granted.

Respectfully submitted.

Charles Fried

Acting Solicitor General

Richard K. W illard

Acting Assistant Attorney General

Kenneth S. Geller

Deputy Solicitor General

Charles A. Rothfeld

Assistant to the Solicitor General

W illiam Kanter

A l J. Daniel, Jr.

July 1985 Attorneys

APPENDIX A

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 82-1019

T o m m y Siia w

v.

L ibrary op Congress, et a l ., appellan ts

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

(Civil Action No. 79-00325)

Argued September 9, 1982

Decided November 6, 1984

Before: Robinson , Chief Judge, W ald and Gin s -

burg, Circuit Judges.

(la)

2a

Opinion for the Court filed by Chief Judge Robin

so n .

Dissenting Opinion filed by Circuit Judge Gins-

BURG.

Robinson , Chief Judge: A corollary to the doc

trine of sovereign immunity exempts the United

States from liability for interest absent its express

consent thereto.1 2 The sole issue on this appeal is

whether the District Court dishonored that precept

when, in assessing an attorneys’ fee against the

United States, it effected a 30 percent upward adjust

ment of the lodestar3 to compensate the attorney for

delay in receipt of payment.

We sustain the adjustment alternatively on two

grounds. First, we conclude that the language o f the

statute authorizing allowances of attorneys’ fees

against the United States in employment-discrimina

tion cases waives its sovereign immunity with respect

to the delay component of the fee award. Second, we

find that component validated by a line of cases re

laxing the traditional rigor of the sovereign-immu

nity doctrine.

I

In 1976 and again in 1977, Tommy Shaw, a black

employee of the Library of Congress, submitted com

plaints of job-related racial discrimination to the Li

1 See Part IV infra.

2 The lodestar component of an attorneys’ fee is the product

of “ the number of hours reasonably expended multiplied by

a reasonable hourly rate.” Copeland V. Marshall, 205 U.S.App.

D.C. 390, 401, 641 F.2d 880, 891 (en banc 1980).

3a

brary’s Equal Employment Office.3 In 1978, after the

Library remained resistant to these complaints,

Shaw’s counsel engaged in administrative proceed

ings and during the course thereof entered into ne

gotiations which culminated in a settlement agree

ment.4 5 6 As part of the settlement, the Library agreed

to promote Shaw retroactively with backpay provided

the Comptroller General first determined that the Li

brary had authority to do so without a specific find

ing o f racial discrimination.® The Comptroller Gen

eral, however, held that the Library lacked power

under the Back Pay Act of 19668 to pursue that

course.7

Dissatisfied with this turn of events, Shaw sued

in the District Court8 and ultimately prevailed on

8 See Complaint If 12, Shaw v. Library of Congress, Civ. No.

79-0325 (D.D.C.) (filed Feb. 1, 1979), Record Document (R.

Doc.) 1 [hereinafter cited as Complaint].

4 Settlement Agreement and General Release (filed Feb. 1,

1979), Exhibit 1 to Complaint, supra note 3, R. Doc. 1 [here

inafter cited at Settlement Agreement].

5 Id. at pp. 4-5, R. Doc. 1.

6 Act of Mar. 30, 1966, Pub. L. No. 90-380, § 1(34) (c), 80

Stat. 94 (codified as amended at 5 U.S.C. §§ 5595-5596

(1982)).

7 Letter from Paul G. Dembling to Donald C. Curran (Nov.

2, 1978), Exhibit 2 to Complaint, supra note 3, R. Doc. 1. The

Comptroller General declined to consider whether the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, tit. VII, § 717 (b ) , 78

Stat. 251, as amended by the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261, § 11, 86 Stat. I l l (codified

as amended at 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16(b) (1982)), authorized

retroactive promotion and backpay in Shaw’s instance, pre

sumably because the Library inquired only as to its authority

under the Back Pay Act.

8 Shaw V. Library of Congress, Civ. No. 79-0325 (D.D.C.).

4a

his position that the Library had authority to afford

the relief specified in the settlement accord.9 As a

result of Shaw’s victory, the court ordered that he

be awarded litigation costs and reasonable attorneys’

fees,10 withholding, however, determination of the dol

lar amount thereof until after further proceedings

and this court’s decision in Copeland v. Marshall,11

then pending en banc.12 By this time, primary re

sponsibility for prosecution of Shaw’s claim had de

veloped upon new lawyers, but the efforts of his ear

lier counsel before the Library and in the District

Court had involved considerable time and energy.13

After our decision in Copeland was announced, coun

sel moved for an allowance of attorneys’ fees,14 re

questing compensation at the rate of $85 per hour

9 Shaw v. Library of Congress, 479 F.Supp. 945, 947-949

(D.D.C. 1979).

10 Id. at 950.

11 Supra note 2.

12 Shaw v. Library of Congress, supra note 9, 479 F.Supp.

at 950.

13 Shalon Ralph, the fee claimant in this litigation, succeeded

another attorney as Shaw’s counsel in early 1978, while the

case was in its administrative phase. Additional counsel for

Shaw entered the picture shortly thereafter, and their claims

for attorneys’ fees have been settled. Ralph participated in

the administrative proceedings and negotiations, and assisted

the other counsel in preparation of a brief to the Comptroller

General and in their representation of Shaw in the District

Court. Hereinafter when we speak of Shaw’s counsel, we

refer to Ralph.

14 Plaintiff’s Motion for Award of Attorney’s Fees and

Costs, Shaw V. Library of Congress, Civ. No. 79-0325 (D.D.C.)

(filed May 11,1981), R. Doc. 37.

5a

for 103.75 hours of work on Shaw’s behalf during

the course of those proceedings.15

Largely dismissing the Library’s challenges to both

the hourly rate and the number of hours claimed by

Shaw’s counsel,1'6 the District Court computed a lode

star of $8,435,17 based on 99 hours of work at the

$85 proposed hourly rate, excluding from its calcula

tion 4.75 hours which counsel devoted to research in

an abortive effort to impart a class-action aspect to

Shaw’s administrative complaints.18 The court then

reduced the lodestar by 20 percent to reflect the qual

ity of counsel’s representation.1® Lastly, and most

importantly for this appeal, the court increased the

lodestar by 30 percent to compensate counsel for the

delay in actual payment for the legal services he had

rendered.20 The court explained:

This case should have ended in August 1978, or

at the latest in November of that year. If

[Shaw’s counsel] had been compensated at about

that time, he could have invested the money at

an average yield of not less than 10% per year.

15 Id. § 11(2), R. Doc. 37.

10 See Defendant’s Memorandum of Points and Authorities

in Opposition to Motion for Attorney’s Fees, Shaw V. Library

of Congress, Civ. No. 79-0325 (D.D.C.) (filed June 11, 1981),

It. Doc. 41.

17 The District Court made a mathematical mistake when it

calculated the lodestar at $8,435; 99 hours of work at $85 per

hour comes to $8,415, not $8,435. We accordingly treat the

lodestar as lowered to $8,415.

18 Shaw V. Library of Congress, Civ. No. 79-0325 (D.D.C.

Nov. 4, 1981) (memorandum) at 6-8, R. Doc. 45.

18 Id. at 8-9, R. Doc. 45.

20 Id. at 9-10, R. 45.

6a

It is the fault of neither [Shaw] nor [counsel]

that payment was not made sooner. It is rea

sonable to assume that if payment is made

promptly, counsel will receive his reimbursement

by December 1, 1981. Accordingly, the accom

panying order reflects an upward adjustment of

30% for the delay.21

Then, offsetting the 30 percent increase in the lode

star by the 20 percent reduction in the lodestar, the

District Court granted a net 10 percent addition to

the lodestar22 23 and, accordingly, awarded counsel a

fee of $9,278.50.28 The Library has appealed,24 * * * ar

21 Id., R. Doc. 45 (footnote omitted). The court further jus

tified the adjustment on the ground that the Library might

earlier have tendered partial payment to counsel despite the

outstanding appeal in Copeland v. Marshall. Id. at 9 n.4, R.

Doc. 45.

22 Id. at 10, R. Doc. 45. Our dissenting colleague implies

that the District Court unfairly penalized counsel by utilizing

simple rather than compound interest, and committed arith

metic error when it increased the lodestar by 30% and then

reduced that figure by 20% of the lodestar, rather than by

20 % of the upwardly adj usted figure. See Dissenting Opinion

(Dis. Op.) at 16 n. 13. Judges have broad latitude in setting

attorneys’ fees, Copeland V. Marshall, supra note 2, 205 U.S.

App.D.C. at 411, 641 F.2d at 901; Cuneo v. Rumsfeld, 180

U.S.App.D.C. 184, 192, 553 F.2d 1360, 1368 (1977), and in

neither of these respects can we say that the District Court

abused its discretion.

23 Shaw V. Library of Congress, supra note 18, at 10, R. Doc.

45. The court also awarded Shaw $47.50 in costs, id., which

the Library does not challenge on appeal.

24 After oral argument on appeal, we ordered the Library

to pay to counsel $6,779.50, the portion of the award not in

dispute. Shaw V. Library of Congress, No. 82-1019 (D.C. Cir.

Jan. 19,1983) (partialjudgment).

7a

guing that the 30 percent upward adjustment for de

lay infringes the rule that interest may not he as

sessed against the United States in the absence of

waiver.25

II

The issue posed on appeal is hardly one of first

impression. In Copeland v. Marshall,26 we declared

en banc that the United States can be held liable un

der Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 27 for

attorneys’ fees in an amount augmented to compen

sate for the lag attending payment. We said:

The delay in receipt of payment for services

rendered is an additional factor that may be in

corporated into a contingency adjustment. The

hourly rates used in the “ lodestar” represent the

prevailing rate for clients who typically pay

their bills promptly. Court-awarded fees nor

mally are received long after the legal services

are rendered. That delay can present cash-flow

problems for the attorneys. In any event, pay

ment today for services rendered long in the past

deprives the eventual recipient of the value of

the use of the money in the meantime, which

use, particularly in an inflationary era, is valu

able. A percentage adjustment to reflect the de

lay in receipt of payment therefore may be ap

propriate.28

25 Brief for Appellant at 5-8.

26 Supra note 2.

27 Pub. L. No. 88-352, tit. VII, § 706 (k), 78 Stat. 261 (1964)

(codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-5(k) (1982))

[hereinafter cited as codified].

28 Copeland V. Marshall, supra note 2, 205 U.S.App.D.C. at

403, 641 F.2d at 893 (footnotes and citation omitted). We also

8a

We have subsequently reaffirmed this principle29

and, indeed, have upheld an award of attorneys’ fees

endorsed calculation of the lodestar on presently-prevailing

hourly rates as an alternative method of compensating attor

neys for delay. Id. at 403 n.23, 641 F.2d at 893 n.23.

We may note here that, regardless of whether the defend

ant is the United States or a private party, a delay-in-payment

adjustment would be appropriate only where the lodestar is

the per-hour charge to clients who pay when billed. Murray v.

Weinberger, Civ. No. 83-1680 (D.C. Cir. Aug. 24, 1984) at 17.

If the lodestar represents a higher rate charged clients who

sue under fee-shifting statutes, it has already taken into ac

count the pecuniary disadvantage resulting from the lengthy

wait for payment ordinarily encountered under such statutes.

In such an instance, an upward adjustment for delay would, of

course, result in the attorney being paid twice for the delay. It

appears that the cases relied on by the District Court in set

ting the $85 per-hour lodestar for counsel here did not in any

way include a delay element in their own per-hour rate calcula

tions. North Slope Borough V. Andrus, 515 F.Supp. 961

(D.D.C. 1981), rev’d on other grounds sub nom. Katkovik V.

Watt, 223 U.S.App.D.C. 37, 689 F.2d 222 (1982) ; Bachman V.

Pertschuk, 19 Empl. Practice. Dec. (CCH) Tf 9044, at 6507

(D.D.C. 1979). See Shaw V. Library of Congress, supra note

18, at 7, E. Doc. 45. Our disposition of this appeal, however,

will include a remand in order that the District Court may

make certain that counsel is not being awarded double com

pensation for the delay.

29 Jordan v. United States Dep’t of Justice, 223 U.S.App.

D.C. 325, 329, 691 F.2d 514, 518 (1982) (involving claim for

attorneys’ fees against United States under provision of Free

dom of Information Act (citing Copeland V. Marshall, supra

note 2, 205 U.S.App.D.C. at 402-403, 641 F.2d at 892-893, for

proposition that attorneys’ fee award may reflect delay in

payment)) ; National Ass’n of Concerned Veterans V. Secre

tary of Defense, 219 U.S.App.D.C. 94, 103, 110, 675 F.2d

1319, 1328, 1335 (1982) (affirming propriety of adjusting

attorneys’-fee award against United States to compensate for

delay in two Freedom of Information Act cases and one Title

VII case).

9a

against the United States that in fact was adjusted

upward to compensate for delay.30

Despite the seemingly clear applicability of these

precedents, however, we do not rest our disposition

on stare decisis alone. Whether an upward delay

adjustment in an attorneys’-fee award satisfies the

rigorous requirements of the sovereign-immunity doc

trine is an issue we have dealt with only peripher

ally,31 and one we have never squarely addressed. We

recognize, too, the jurisdictional implications of any

legal bar created by that doctrine, and acknowledge

the existence o f decisions of this circuit arguably

in conflict with Copeland and its progeny on this

point;3'2 We therefore opt to consider the Library’s

™EDF v. EPA, 217 U.S.App.D.C. 189, 206, 672 F.2d 42, 59

(1982). Cf. Murray v. Weinberger, supra note 28, at 16-19

(allowing a properly-justified adjustment to lodestar for delay-

in payment in a Title VII attorneys’ fee claim).

31 See Copeland V. Marshall, supra note 2, 205 U.S.App.D.C.

at 404-405 & n.25, 641 F.2d at 894-895 & n.25 (holding that

liability for attorneys’ fees under Title VII is the same for the

United States as for any private party) ; Holly v. Chasen, 205

U.S.App.D.C. 273, 276, 639 F.2d 795, 798, cert, denied, 454

U.S. 822, 102 S.Ct. 107, 70 L.Ed.2d 94 (1981) (overturning,

on grounds of sovereign immunity, award of interest on judg

ment against United States in a Freedom of Information Act

case, but expressly reserving question whether upward ad

justment in an attorneys’ fee award to compensate for delay

would likewise be invalid).

3:2 See Holly V. Chasen, supra note 31; Blake V. Calif ano, 200

U.S.App.D.C. 27, 626 F.2d 891 (1980). The dissent’s use of

broad language in Segar V. Smith, ------ U.S.App.D.C. ------ ,

------ , 738 F.2d 1249, 1296 (1984), may give the impression

that the attorneys’-fee provision at issue here, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(k) (1982), was involved in Segar. Dis. Op. at 5.

Segar concerned only an award of interest under the backpay

section of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) ; the dispute did

10a

argument much as if it were presented upon a clean

slate,

III

The initial inquiry, of course, is whether the Dis

trict Court’s 30 percent augmentation of the lodestar

for delay in payment of the fee constitutes “ interest”

against the United States within the contemplation

of the rule invoked by the Library. Shaw character

izes this component of the fee award as a proper

ingredient of a reasonable attorneys’ fee, in contra

distinction to interest.* 33 The only way to determine

whether this addition to the lodestar is condemned

by the traditional interest rule is to ascertain what

that rule prohibits.

Perhaps the clearest example of interest appears

when a court, after calculating the amount of mone

tary judgment, adds a percentage of that amount to

compensate the claimant for loss of use of the money

during the period between the claimant’s initial en

titlement to the money and the day the judgment is

rendered.34 Here the long-established rule refuses to

view the sovereign as having consented to the addi

tion, even though consent to suit on the claim has

been established.35 The same results follow court-

awarded sums which, though not interest calculated

not extend to interest under the attorneys’-fee provision, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (1982), which uses language wholly dif

ferent from that employed in the backpay section.

33 Brief for Appellant at 10.

84 E.g., United States V. Thayer-West Point Hotel Co., 329

U.S. 585, 587-588, 67 S.Ct. 398, 399, 91 L.Ed. 521, 525 (1947).

85 E.g., United States V. Alcea Band of Tillamooks, 341 U.S.

48, 71 S.Ct. 552, 95 L.Ed. 738 (1951) ; United States V. Goltra,

312 U.S. 203, 61 S.Ct. 487, 85 L.Ed. 776 (1941).

11a

in the classic manner, nonetheless are functionally

equivalent to interest. Thus the Supreme Court has

rejected a contention that an increase in an assess

ment by the Court of Claims against the United

States, made as compensation for loss of use and oc

cupation of a mining claim appropriated by the

United States years earlier, was “ compensation”

rather than interest.3'8 The Court reasoned that be

cause “ the loss of the use of the money results from

the failure to collect sooner a claim held to have ac

crued when the company’s property was taken, that

which the company seeks to recover is, in substance,

interest.” 36 37 We ourselves recently held an “ inflation

adjustment” in awards of backpay to federal em

ployees amounted to interest against the United

States because it served “ the same general end of

compensating the recipient for differences in the

worth of her award between the date of actual re

ceipt and the date as of which the money should have

been paid.” 38

In the case at bar, the District Court’s 30 percent

addition to the lodestar was designed to reimburse

Shaw’s counsel for the decrease in value of his un

collected legal fee between the date on which he con

cluded his legal services and the court’s estimated

date of likely actual receipt.39 By the court’s own

36 United States V. North Am. Transp. & Trading Co., 253

U.S. 330, 40 S.Ct. 518, 64 L.Ed. 935 (1920).

37 Id. at 338, 40 S.Ct. at 521, 64 L.Ed. at 939.

38 Blake v. Califano, supra note 32, 200 U.S.App.D.C. at 31,

626 F.2d at 895. Accord, Saunders v. Claytor, 629 F.2d 596,

598 (9th Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 450 U.S. 980, 101 S.Ct. 1515,

67 L.Ed.2d 815 (1981) (“ [i,]n essence, the inflation factor ad

justment is a disguised interest award” ).

89 See text supra at note 21.

12a

description, the addition was based on a rough de

termination of the “ average yield” of the amount of

the fee if invested at 10 percent per annum for three

years.40 We think the adjustment falls well within

the contours of the interest concept. Only by ignor

ing applicable caselaw as well as the real nature of

the disputed adjustment could we find anything other

than an assessment of interest against the United

States.41 We proceed, then, to the Library’s conten

40 Shaw V. Library of Congress, supra note 18, at 9-10, R.

Doc. 45.

41 See United States V. Mescalero Apache Tribe, 518 F.2d

1309, 1322 (Ct. Cl. 1975), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 911, 96 S.Ct.

1506, 47 L.Ed.2d 761 (1976) (“the character or nature of

‘interest’ cannot be changed by calling it ‘damages,’ ‘loss,’

‘earned increment,’ ‘just compensation,’ ‘discount,’ ‘offset,’ or

‘penalty,’ or any other term, because it is still interest and the

no-interest rule applies to it” ) (footnote omitted).

The dissent suggests that an upward adjustment of an at

torneys’ fee to compensate for delayed receipt can be differ

entiated from interest on the ground that the former applies

“prospectively” while interest is awarded “ retrospectively.”

Dis. Op. at 1, 4-5. This distinction apparently takes on disposi

tive significance. We note that any prospectivity here is fic

tional, for an award under a fee-shifting statute benefiting

only a party prevailing in litigation can never be made pro

spectively. More importanly, we cannot see why the moment

in time at or as of which compensation for delayed receipt of

payment is calculated should matter; for us, it is the reason

why the fee is adjusted upward that is vital. Addition of a

delay factor to the lodestar serves only to compensate the at

torney for loss of the use of earned money from the time of

rendition of services to the time of receipt of the fee. See text

supra at note 28, quoting Copeland V. Marshall, supra note 2,

205 U.S.App.D.C. at 403, 641 F.2d at 893. The dissent itself,

in distinguishing the delay factor from interest, characterizes

the delay factor thus: “ an attorney embarking on services for

which he or she anticipates payment ultimately, but not

13a

tion that the District Court’s action in this regard

disregards the dictates of the doctrine of sovereign

immunity.

IV

The United States cannot be subjected to monetary

liability save pursuant to a waiver of its sovereign

immunity.42 Moreover, the scope of such a waiver is to<

be strictly construed.43 The instant case involves a

corollary of these principles, which for convenience

we term the “ interest rule.” By this rule, the United

States may not be held liable for interest absent an

express waiver of its immunity.44 The question we

promptly, may factor in the expected delay.” Dis. Op. at 1.

By this we can only assume that our colleague means that the

increase is to compensate for a supposed possibility of delayed

payment, and consequently for deprivation of the use of the

fee money during the period of delay. We are unable to dis

tinguish between that and compensation for the use, forbear

ance or detention of money—the common understanding of

interest. If the delay factor sounds like interest, acts like in

terest and, most of all, compensates exactly as interest would,

we feel constrained to treat It as interest for purposes of the

sovereign-immunity rule.

42 E.g., United States V. Sherwood, 312 U.S. 584, 586, 61

S.Ct. 767, 769, 85 L.Ed. 1058, 1061 (1941) ; United States v.

Lee, 106 U.S. 196, 1 S.Ct. 240, 27 L.Ed. 171 (1882) ; United

States v. McLemore, 45 U.S. (4 How.) 286, 11 L.Ed. 977

(1846).

43 E.g., United States v. Sherwood, supra note 42, 312 U.S.

at 590, 61 S.Ct. at 771, 85 L.Ed. at 1063.

44 E.g., United States V. Louisiana, 446 U.S. 253, 264-265,

100 S.Ct. 1618, 1626, 64 L.Ed.2d 196, 208 (1980). Courts

have not been entirely consistent in applying this rule, how

ever. Compare Henkels V. Sutherland, 271 U.S. 298, 46 S.Ct.

524, 70 L.Ed. 953 (1926) (allowing interest as component of

assessment against United States for confiscation of securities,

14a

face here is whether Congress has waived that im

munity with respect to an allowance of interest as

part of an attorneys’ fee awarded, as here, under

Title VII.

The relevant section of Title VII provides that

[i]n any action or proceeding under this sub-

chapter the court, in its discretion, may allow

the prevailing party, other than the i[Equal Em

ployment Opportunity] Commission or the United

States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the

costs, and the Commission and the United States

shall be liable for costs the same as a private

person.4B

A private person, of course, may be held liable for

interest as an ingredient of a Title VII attorneys’- 45

in part to prevent unjust enrichment), with Angarica V.

Bayard, 127 U.S. 251, 8 S.Ct. 1156, 32 L.Ed. 159 (1888) (dis

allowing interest as an item in assessment against United

States for money withheld from awardee). Courts also have

established an exception to the rule in inverse eminent domain

cases, in which interest has been allowed as an element of the

constitutional measure of just compensation. See Blake V.

Califano, supra note 27, 200 U.S.App.D.C. at 29 n.5, 626 F.2d

at 893 n.5, and cases cited therein. For a discussion of two

other exceptions, see note 90 and Part V infra.

45 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (1982) (emphasis added). This

section was made applicable to the United States in cases such

as this by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972,

Pub. L. No. 92-261, § 11, 86 Stat. I l l (codified at 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-16(d) (1982)). Though on occasion we have found

that asserted statutory waivers of immunity from interest lia

bility were not “ express,” e.g., Holly v. Chasen, supra note 31;

Blake V. Califano, supra note 32, we have not heretofore ad

dressed the question whether the cited section effects such

a waiver.

15a

fees award,46 and this section subjects the United

States to liability for “costs the same as a private

person,” and authorizes assessment of a “ reasonable

attorney’s fee as part of the costs.” We conclude

that Congress thus has waived the immunity of the

United States from liability for interest as a com

ponent o f an attorneys’ fee allowed under Title VII.

The statutory waiver is express, and its range is

defined in unmistakable language. To say that a

private person, but not the United States, is liable

under Title VII for interest as an element o f an at

torneys’ fee would rob the unambiguous statutory

language of its plain meaning. It would defeat the

statutory imposition upon the United States of a

liability for costs, and the statutory inclusion of “ a

reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs,” iden

tical to that of a private party in similar circum

stances. The scope-setting statutory words— “ the

same as a private person”— mark out the United

States’ liability for attorneys’ fees as well as costs

in the traditional sense. Our responsibility as judges

is to enforce this provision according to its terms.47

46 Courts have broad power to allow interest in private-

sector cases, e.g., Rodgers v. United States, 332 U.S. 371, 373-

374, 68 S.Ct. 5, 7, 92 L.Ed. 3, 6-7 (1947), and have affirmed

this prerogative in attorneys’-fee awards under Title VII. See

Chrwpliwy V. Uniroyal, Inc., 670 F.2d 760, 764 & n.6 (7th Cir.

1982), cert, denied,------ U.S.------- , 103 S.Ct. 2428, 77 L.Ed.2d

1315 (1983) ; Brown V. Gillette Co., 536 F.Supp. 113, 123-124

(D. Mass. 1982).

47 Courts consistently have declined to depart from the plain

meaning of statutory language absent clear indication of a

contrary legislative intent, e.g., United States V. Tiirkette, 452

U.S. 576, 580, 101 S.Ct. 2524, 2527, 69 L.Ed.2d 246, 252

(1981), and have recognized an obligation to avoid a construc

tion of a statutory provision that obviates any term thereof,

16a

We think Congress articulated its goal clearly

enough by providing for governmental liability “ the

same as a private person.” Conceivably, Congress

might have attempted to effectuate its purpose by

legislation listing each item of costs, including in

terest, for which the United States might be held

accountable. That approach, however, could well have

led to the discovery of interstices among the enumer

ated items, especially since the courts would have had

to obey the rule requiring strict construction of waiv

ers of sovereign immunity;48 its adoption, conse

quently, would not likely have achieved the congres

sional objective, manifest here, that the United

States be treated no differently from private parties

in similar circumstances.49 It seems to us that, de-

e,g., United States V. Menasche, 348 U.S. 528, 538-539, 75 S.Ct.

513, 520, 99 L.Ed. 615, 624 (1955).

The dissent contends that because the word “costs” his

torically has not included interest as an ingredient, the statu

tory waiver of the United States’ immunity from liability for

“ costs” cannot reasonably, much less strictly, be construed to

extend to interest. Dis. Op. at 7. We cannot subscribe to

this reasoning. The Title VII section under scrutiny in terms

rejects the traditional concept of costs. It repudiates the

commonly-understood difference between costs and attorneys’

fees, see, e.g., Roadway Express, Inc. v. Piper, 447 U.S. 752,

759-761, 100 S.Ct. 2455, 2460-2461, 65 L.Ed.2d 488, 496-498

(1980) ; Baez v. United States Dep’t of Justice, 221 U.S.App.

D.C. 477, 480-483, 684 F.2d 999, 1002-1005 (en banc 1982) ;

10 C. Wright, A. Miller & M. Kane, Federal Practice § 2666

at 173-174 (2d ed. 1983), by explicitly establishing attorneys’

fees as a subset of costs.

48 See note 43 supra and accompanying text.

49 As another example, Congress could have enacted a stat

ute providing that “ the United States shall be liable for costs,

including but not limited to interest, the same as a private

person,” thus stating the rule of equal treatment and specify-

17a

spite the availability of alternative statutory schemes

waiving immunity from interest liability, there is

simply no more direct and effective way to ensure

complete parity between the United States and other

litigants with respect to costs than to say so in so

many words. That Congress did so in this section, we

conclude, evinces an “ express” waiver within the

meaning of the interest rule.

Congress obviously understood the broad sweep of

language which makes the United States just as li

able as “ a private person.” In the Federal Torts

[sic] Claims Act,80 which later we discuss further,®1

Congress made the United States liable for certain

torts “ in the same manner and to the same extent as

a private individual under like circumstances,” 5,2 but

immediately curtailed the obvious import of this lan

guage by providing that the United States “ shall not

be liable for interest prior to judgment,” 68 It is dif

ficult to understand why Congress bothered to ex

clude pre-judgment interest if the imposition upon * 50

ing interest as an item of possible recovery. We think it an

unnecessarily stringent application of the interest rule, how

ever, to treat the waiver here at issue not “express” with re

gard to the interest component of an attorneys’-fee award sim

ply because Congress did not express itself in precisely that

form. To do so would defeat the plain meaning of the relevant

statutory language Congress did use, and would penalize Con

gress for failing to insert redundant language into an already

clearly-written and easily-applied waiver of immunity.

50 Act of Aug. 2, 1946, ch. 753, 60 Stat. 812 (codified as

amended at 28 U.S.C. §§ 2671 et seq. and other scattered sec

tions of 28 U.S.C. (1982)) [hereinafter cited as codified].

81 See text infra at notes 91-97.

82 42 U.S.C. §2674 (1982).

83 Id.

18a

the United States of liability “ to the same extent as

a private individual under like circumstances” was

insufficient to constitute an express waiver of liabil

ity for that interest.

That the attorney’s-fee section of Title VII does

not actually use the word “ interest” does not, in our

view, make the waiver any less express. Notwith

standing the long history and wide variety of verbal

articulations of the interest rule, we have not un

covered a single case supporting the proposition that

a waiver of sovereign immunity is not express merely

on that account.64 In fact, several decisions weigh

against that position. The Supreme Court has held

that Congress may satisfy the requirements of an

analogous rule— that the United States is not bound

by its own statutes unless expressly named therein 54 55

54 Most of the cases invoking the interest rule to disallow

interest against the United States have done so with respect to

two types of statutes. Some have done so in the context of a

statute not clearly or even apparently naming the United

States as potentially subject to its provisions. E.g., Holly V.

Chasen, supra note 31, 205 U.S.App.D.C. at 274, 639 F.2d at

796 (construing 28 U.S.C. § 1961 (1982)). Others have re

fused to find waivers in the context of gelatinous or extremely

general statutory language, such as those entitling parties

“ any other equitable relief as the court deems appropriate,”

Blake v. Califano, supra note 32, 200 U.S.App.D.C. at 29-31,

626 F.2d at 893-895 (construing 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)

(1976)), “ just compensation,” e.g., United States v. Goltra,