Cypress v. Newport News General and Non-Sectarian Hospital Association, Inc. Appellant's Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cypress v. Newport News General and Non-Sectarian Hospital Association, Inc. Appellant's Reply Brief, 1966. 1ef4d1df-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c953b4bb-3b6a-4ebe-b0d6-4336bb6d1ebd/cypress-v-newport-news-general-and-non-sectarian-hospital-association-inc-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

y

4 0y

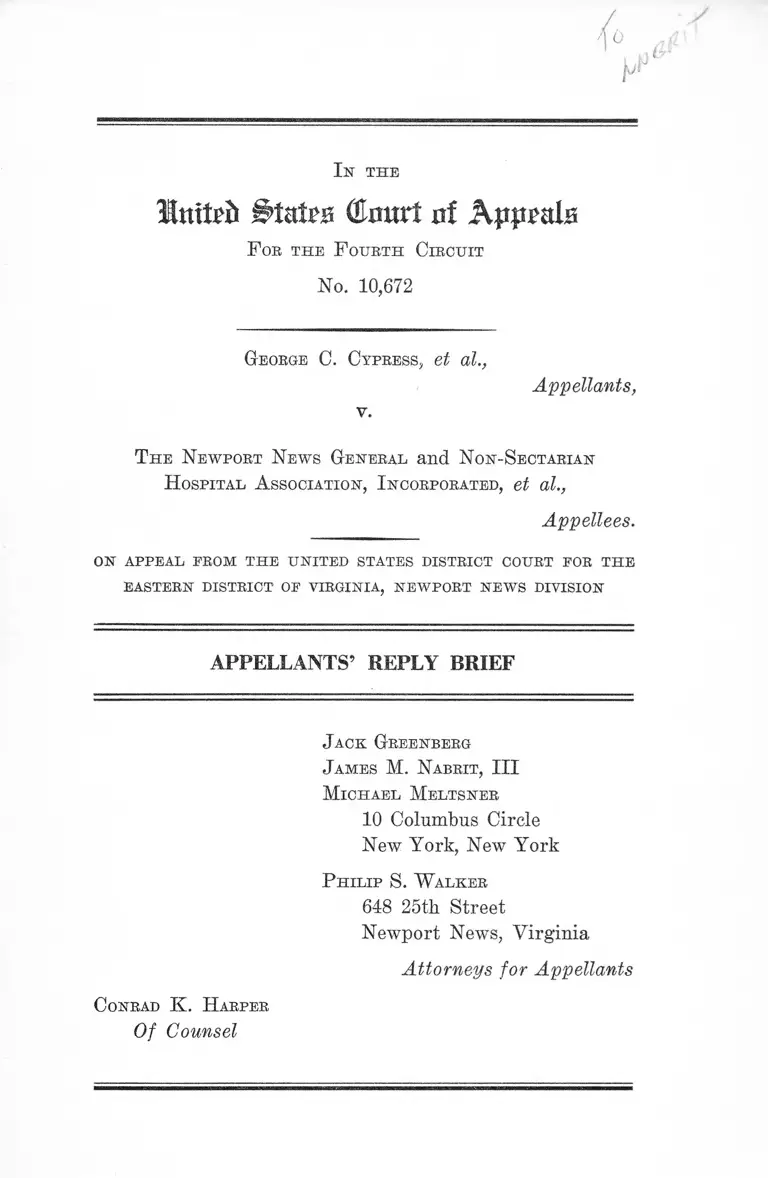

I n the

S>tate (Eniirt ni Appeals

F ob the F ourth Circuit

No. 10,672

George C. Cypress, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

T he N ewport N ews General and N on-S ectarian

H ospital A ssociation, I ncorporated, et al.,

Appellees.

on appeal from the united states district court for the

EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, NEWPORT NEWS DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

P hilip S. W alker

648 25tk Street

Newport News, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

Conrad K. H arper

Of Counsel

I n th e

InitTfr ^tdtm (Eiuirt at Kppmlz

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 10,672

George C. Cypress, et al.,

v.

Appellants,

T he N ewport N ews General and N on-S ectarian

H ospital A ssociation, I ncorporated, et al.,

Appellees.

ON a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t p o r t h e

EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, NEWPORT NEWS DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

In this brief, Negro physicians and patients discuss a

number of points argued by the hospital. We note initially,

however, that while the hospital appears to recognize that

the question before the Court is whether the record sup

ports a findings of discrimination against Negro physi

cians and patients, the hospital’s brief avoids discussion

of significant portions of the record. For example, the hos

pital does not meaningfully discuss the rejection of Dr. C.

Waldo Scott. The probative force of the unexplained rejec

tion of Dr. Scott is great, especially in light of the un

contradicted testimony of his (and Dr. Cypress’ ) superior

skill and background. Secondly, the hospital’s treatment

of the facts suggests that the two Negro physicians possess

only some minimum skills. The record flatly contradicts

2

this and the hospital offers no explanation of the fact that

the peers of the Negro physicians, certified specialists in

pediatrics and surgery, are members of the hospital staff.

(See page 5 of appellants’ brief.) There is also no mean

ingful explanation for the hospital’s failure to introduce

any evidence of any reason why the Negro physicians

should have been rejected subsequent to the hospital’s af

firmative allegation that membership had been denied for

good cause. The failure of the hospital at trial and in its

brief to qualify in any way the skill and character of the

Negro physicians leaves totally uncontradicted statements

such as that of the Health Director of the City of New

port News, a former Colonel in the United States Army

Medical Corps, who summarized his opinion of Dr. Cypress

by stating:

Well, in my 29 years of practice of medicine I have

never been associated with a better pediatrician than

Dr. George C. Cypress and I would recommend him

for any staff (186a).

I

The hospital argues that this is not a proper class ac

tion because more than one class of plaintiffs are joined.

This position reflects a misconception of the place of mis

joinder in federal practice. There is no misjoinder in this

case, but even if there were it would be a problem which

affected the trial, not the pleadings or the disposition of

the case. Rule 21 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

is quite explicit that “Misjoinder of parties is not grounds

for dismissal on an action.” The remedy for misjoinder is

a separate trial of claims:

Any claim against a party may be severed and pro

ceeded with separately. (Ibid)

3

Here, there is no contention that the hospital was prej

udiced at the trial by joinder of Negro physicians and pa

tients and it would be difficult to conceive of the basis for

such contention. It is instructive to compare the only au

thority cited by the hospital for this point, Neiman-Marcus

v. Lait, 13 F.R.D. 311 (S.D. N.Y. 1952). There libel claims

brought by the class representatives of models and sales

men were joined. The models claimed they were libelously

described as prostitutes and the salesmen claimed they

were libelously called homosexuals. The court found the

joinder of these claims would prejudice the defendants “at

the trial” (id. at 317) as the trial would involve a jury

and the presentation to it of evidence concerning quite

different and inflammatory libelous matter (prostitution

and homosexuality). Thus, the prejudice involved in per

mitting the joinder in that case was manifest.

The hospital’s claim, moreover, is conclusively disposed

of by Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323

F.2d 959 (4th. Cir. 1963) and Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F.2d

710 (4th Cir. 1964). In both these leading cases Negro

physicians and patients joined together and obtained in

junctive relief for themselves and others similarly situated.

In the Simkins case Negro dentists joined with Negro doc

tors and also obtained injunctive relief. There is no at

tempt in the hospital’s brief to distinguish Simkins, supra,

and Eaton, supra, on this point.

The hospital also argues that all the Negro physicians

practicing medicine in the Newport News-Hampton area

are insufficient to constitute a class within the means of

Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and that

only the two Negro physicians who have applied for staff

membership at the hospital and not all Negro physicians

in the community should be considered members of the in

terested class. If this reasoning were correct, however,

4

class relief lias been granted improperly in scores of school

desegregation cases where students who have applied for

transfer to “white” schools represented themselves as well

as other Negroes who had not applied. See e.g. Buckner v.

School Board of Greene County, Virginia, 332 F.2d 452

(4th Cir. 1964) and cases cited. It is obvious that all Negro

physicians in the Newport News area have a common in

terest in ending racial exclusion from the best hospital

facility in the community. Three of these Negro physicians

testified at the trial that Dr. Cypress represented them

and their interests. Clearly appellants assert that the hos

pital has “acted or refused to act on grounds generally ap

plicable to the class thereby making appropriate final in

junctive relief or corresponding declaratory relief with

respect to the class as a whole” F.R.C.P. 23(b) 2. See

IIall v. Wertham Bag Cory., 251 F. Supp. 184 (M.D. Tenn.

1966) (existence of discriminatory policy threatens entire

class of employees).

The hospital also cites cases where it was not impractical

to join all persons in the class as parties. There are just

as many decisions holding that a similar number of per

sons were sufficient to support a class action. See e.g.,

Citizens Banking Cory. v. Monticello State Bank, 143 F.2d

261 (8th Cir. 1944) (12 noteholders permitted to represent

28 others in a class action); Tisa v. Potefsky, 90 F. Supp.

175, 181 (S.D. N.Y. 1950) (50 members of an executive

board sufficient for class action). The cases and com

mentators agree that the test of whether a class action

may be brought has nothing to do with a “numbers game.”

Impracticable under Rule 23 is “ only the difficulty or in

convenience of joining all members of the class” or the

burden caused by litigating the issues involved in a piece

meal fashion by numerous suits. Advertising Syecial Na

tional Association v. Federal Trade Commission, 238 F.2d

5

108, 119 (1st Cir. 1956). “ The federal decisions . . .

[reflect] a practical judgment on the particular facts of

the case” 3 Moore’s Federal Practice, §2305, p. 3421.

It is obviously inconvenient and unnecessary to bring

18 busy physicians before the court as party plaintiffs

and clearty burdensome to the district court to settle the

legal obligation of the hospital with respect to Negro

physicians in a number of separate suits for 18 different

law suits would require endless repetitious testimony and

duplication of effort by the court. The district court rec

ognized the adverse consequences of such a result and held

that the Negro physicians are entitled to bring a class ac

tion (292a). As the court stated at trial when it permitted

Negro physicians to testify concerning their interest in the

suit brought by Dr. Cypress “—they would all reapply and

then we might have to go through this ordeal once more”

(235a).

Moreover, in the present case the only consequences of

refusing to permit this “ spurious” class action would be to

force Dr. C. Waldo Scott to commence a new civil action

against the hospital. The trial of such a cause would be a

repetition of testimony and argument already presented to

the court. The class action provisions of the Federal Rules

were formulated to avoid such results so obviously wasteful

of the energy of the judiciary and the resources of litigants.

While the class action provisions of Rule 23 facilitate

the presentation of the claims of Negro physicians by sav

ing the time of the court, the granting of class relief does

not prejudice the hospital in any manner. It is not thereby

enjoined from rejecting a Negro physician who has applied

on a valid nonracial ground for this is a “ spurious” class

action and “ the judgment binds only the original parties

of record and those who intervene and become parties to

6

the action” 3 Moore’s Federal Practice, §23.10, p. 3456.1

The class action decree is therefore a convenient and ap

propriate device for “cleaning up” this litigious situation.

II

The hospital admits that segregation of patients is

practiced, as the district court found, but urges that it is

constitutional because the hospital is not “basically” a

“ segregated hospital.” The notion that the hospital is con

stitutionally permitted to discriminate in general patient

assignment because occasionally it permits Negro and white

pediatric patients in the same room is without merit.2

Negro physicians and patients stress again what should be

apparent! They do not desire, and are not entitled to, the

mixing of sexes, age groups, illnesses, etc. The hospital ad

ministration obviously has discretion to determine the

placement of patients but that discretion is limited to the

extent that they may not adopt a policy or practice of as

signing bed space on the basis of race. When defendants

state as a “ regular thing” Negro and wThite adult patients

1 Of course should relief be granted to Dr. Cypress the decree regardless

of its terms could not expressly or impliedly authorize continued dis

crimination. See Potts v. Flax, 313 F.2d 284, 288-90 (5th Cir. 1963).

2 This Court rejected the position that a little bit of discrimination is

all right in Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College o f South Carolina,

320 F.2d 611, 613 (4th Cir. 963) cert, denied 375 U.S. 314:

The district court in its findings of fact declared that the legislative

policy of South Carolina does not prohibit but discourages integra

tion of the races in its state supported colleges. The distinction

drawn between prohibition and discouragement is a novel one in

legal literature and we must hold it unacceptable under the Constitu

tion of the United States. A state may no more pursue a policy of

discouraging and impeding admission to its educational institutions

on the ground of race than it may maintain a policy of strictly pro

hibiting admission on account of race.

See also Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital at 323 F.2d 959,

968, note 16, where this language was approved by the court.

7

are not put in the same room and attempt to justify this

policy they are attempting to preserve a part of the to

tally repudiated doctrine of “ separate but equal.”

Ill

As discussed at the outset, the hospital’s argument with

respect to exclusion of Negro physicians omits reference to

a number of significant and startling facts shown by the

record. That argument proceeds from the faulty premise

that the Negro physicians have shown only that they meet

“minimum” qualifications for staff membership. On the

contrary, it is difficult to imagine what additional evidence

could have been produced to establish the qualifications of

Dr. Cypress and Dr. Scott. A detailed presentation of the

evidence demonstrating the Negro physicians’ superior

qualifications appears in appellants’ brief but even the

scantiest summary reveals that the hospital’s characteriza

tion of the evidence misses the mark.

To be sure Dr. Cypress and Dr. Scott meet all qualifica

tions—minimum or otherwise— set forth by the hospital in

its bylaws, rules, and regulations but the Negroes proved

much more. After direct observance of them at work in

office and hospital, as well as evaluation of their credentials,

two experts gave a full picture of both physicians as highly

qualified men of above average skill. Their uncontradicted

testimony establishes that on the basis of education, ex

perience, and ability, the Negro physicians would be granted

membership at some of leading hospitals in the United

States. Nor is there anything “minimum” about the de

scription of Dr. Cypress by the health director of the City

of Newport News (186a). In addition, as noted, the Ne

groes have shown that with a single exception the white

peers of Dr. Cypress and Dr. Scott are on the staff of

the hospital, that in fact three-fourths of the white phy

sicians in the community, many with far less training or

expreience (28a-39a) are on the staff while two of the

leaders of the Negro medical community are excluded.

The irony of the hospital’s position is plain. It sug

gests that the Negro physicians do not establish other

than “minimum” qualifications in the face of a great deal

of evidence that both physicians are extremely capable and

experienced but refuses to offer any proof of the manner

in which two Negro physicians failed to measure up to the

Eiverside staff in character, experience, or ability. It

urges that the Negro doctors have met only the standards

set forth in the bylaws but does not say what other stan

dards exist. It claims that the hospital’s standards for

staff membership are reasonable but concedes that the

Negro physicians met all written or articulated standards.

It alleged in the answer that rejection was for just and

good cause but never introduced any evidence of the na

ture of such cause.

In the face of the affirmative evidence of the superior

qualifications of Dr. Cypress and Dr. Scott the hospital

can only justify remaining* silent on the theory that it

has absolute discretion to grant or deny staff membership

and in the exercise of that discretion is not subject to ju

dicial review, a theory apparently accepted by the court

below. This reasoning is, however, incompatible with ap

pellants’ constitutional right to be free from racial dis

crimination at a hospital subject to the restraints of the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. To uphold this con

tention would be to limit Simkins, supra and Eaton, supra,

to the situation of the hospital which admitted that it had

excluded Negro physicians; the ranks of such hospitals

would grow thin and the constitutional rights of Negro

physicians and patients would be rendered meaningless.

9

This Court stated in Chambers v. Hendersonville Board

of Education,------ F .2 d -------- (4th Cir. 1966) :

Tnnnmp.ra.h1e cases have clearly established the prin

ciple that under circumstances such as this where a

history of racial discrimination exists the burden of

proof has been thrown upon the parties having the

power to produce the facts.

In Chambers, the court found discrimination when a

school board failed to produce evidence meriting dismissal

after Negro teachers had shown they met all objective

qualifications. The court adopted the rule as framed by

decisions such as Hernandez v. Texas, 347 TT.S. 475, 480;

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354. While the hospital dis

cusses Pierre, supra, and Hernandez, supra, in its brief

and attempts to distinguish them because those cases in

volve jury discrimination nowhere does the hospital cite or

discuss the Chambers decision. Nor is this Court’s decision

in Johnson v. Branch,------ F .2d -------- (4th Cir. 1966) rely

ing upon Chambers, discussed. Both Chambers and John

son are cited in appellants’ brief.

Likewise, the hospital fails to cite or discuss the leading

authority in this circuit for the proposition that Negroes

may not be excluded by means of a procedure which bur

dens them and not white applicants. Hawkins v. North

Carolina. Dental Society, 355 F.2d 718, 723. In Hawkins,

the court rejected a procedure which required a recom

mendation from two of 1,214 white dentists before admis

sion could be granted and cited in support of this conclu

sion Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962); Hunt

v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847 (N.D. G-a. 1959); Dudley v.

Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University, 150

F. Supp. 900 (E.D. La. 1957). Unaccountably, the Fifth

Circuit cases are discussed in the hospital’s brief but

10

Hawkins is not. But the attempted distinction of even

those cases fails because the three-fourths majority vote

of the medical staff required for admission is obviously

more of a burden to Negro applicants than the procedures

required in the Fifth Circuit cases or in Hawkins.

At the conclusion of the hospital’s brief reference is

made to a letter of eligibility received by the hospital from

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare clearing

it to participate in federally assisted programs under

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The letter is

dated June 30, 1966. Appellants have inquired about this

clearance and have received a letter (July 29, 1966) from

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare which

is reprinted as Appendix A. This letter clearly states that

whatever else it may mean the “clearance” does not purport

to be a judgment on the practices challenged in this law

suit. “ To the extent” the Department considered such

practices its investigators merely “accepted without ques

tion or an individual judgment, the ruling of the district

court.” The letter states that the administrative clearance

“did not involve and vTas not intended to influence the is

sues in the case of Cypress v. The Newport News General

and Non-Sectarian Hospital Association, Inc. No. 10,672,

now pending in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit.”

This law suit was commenced in 1963 in order to enjoin

the practices of racial exclusion and segregation. Nothing

determined by the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare two years after the trial in this case can possibly

determine whether appellants are entitled to relief. How

ever, the available evidence confirms that racially discrim

inatory policies persist at the Riverside hospital. No Negro

physicians have been placed on the staff and, as the hos

11

pital’s brief reveals, page 21, the patient assignment policy

has remained unchanged.

It is in this context that one must appraise the hos

pital’s suggestion that in 1966 Negro physicians should,

without injunctive relief, reapply to the hospital and sub

mit themselves to the “hearing” outlined in the district

court’s opinion. The character of that hearing is fully de

scribed in appellants’ brief, pp. 22-24. Briefly, after con

cluding that Negro physicians were not entitled to relief,

the court suggested that they should now be permitted to

reapply. On what basis the district court concluded that

absent such a statement in its opinion the Negro physi

cians could not reapply is not clear. However, upon reap

plication, an applicant could request a “ conference” or

“hearing” at his own cost which would be held without

attorneys, cross-examination, sworn testimony, burden of

proof, or judicial review and only after the Negro executed

the broadest possible release. Appellants believe that the

procedures described by the district court failed to satisfy

the most elementary requirements of a fair hearing, but

this court should not enter into any appraisal of the

procedures suggested by the district court. That court

clearly and unmistakably held that appellants were not

entitled to relief and had not established racial discrimina

tion in exclusion of Negro physicians and segregation of

Negro patients.

Although appellants reject the procedure outlined by the

district court, and have appealed the ruling of that court,

they have not objected to any meaningful settlement of the

case which might arise from a change of hospital policy.

Thus, on or about July 7, 1966, Dr. Cypress once again

applied for membership on the Riverside staff. As of the

date this brief is prepared, August 18, 1966, the hospital

has failed to act on Dr. Cypress’ application. It is plain,

12

therefore, that Riverside hospital is still unwilling to

accept Negro physicians on its staff.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

P hilip S. W alker

648 25th Street

Newport News, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

Conrad K . H arper

Of Counsel

D E P A R TM E N T O F H E A L T H , E D U C A TIO N , AND W ELFA R E

W A S H I N G T O N , D . C . 2020]

OFFICE OF TH E SECRETARY July 29, 1966

Mr. Michael Meltsner, Esq.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Dear Mr. Meltsner:

At your request this Office has reviewed the Public Health Service's file

on the Riverside Hospital in Newport News, Virginia, which file indicates

that the Riverside Hospital was cleared for participation in the Medicare

Program on June 30, 1966.

Based on our review of material in the file and on discussions with Public

Health Service personnel who were involved in the decision to clear this

hospital, we have concluded that the basis for clearance did not involve

and was not intended to influence the issues in the case of Cypress v. the

Newport News, General and Non-Secretarial Hospital Association, Inc■ No.

10672, now pending in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

The major issues in the litigation raise Constitutional questions as to

(1) whether or not the hospital refused to accept Dr. George C . Cypress

and other Negro doctors as members of its medical staff because of race

or because of the application of standards and requirements not applied to

white doctors; and (2) whether or not the Constitution requires that Negro

patients be assigned to rooms in the hospital on a non-racial basis.

This Department as part of its responsibility under Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, requires that all HEW programs receiving Federal

financial assistance be operated without regard to race, color or national

origin. Thus, in order to become eligible for participation in the Medicare

Program, hospitals are required both to indicate willingness to operate on

a completely non-discriminatory basis and provide some evidence that the

non-discriminatory policy has been placed in effect. Among the specific

actions that Riverside Hospital was requested to take was a public announce

ment by individual letter to Negro physicians in the area, advising that

applications for staff privileges would be accepted and evaluated by the

hospital regardless of race, color or national origin. The hospital sent

out such notices to 20 Negro physicians, including the two plaintiffs, on

June 29, 1966. In addition, the hospital submitted a report of bed assign

ments for a two-week period that indicated patients during this period were

assigned to rooms without regard to race.

13

APPENDIX A

14

Appendix A

(See Opposite)

Page -2 -

The decision to permit the Riverside Hospital to participate in the Medicare

Program was based on the evaluation of the Public Health Service staff that

the hospital's performance met the minimum standards for clearance. Public

Health Service personnel indicate that while they were aware of the pending

litigation, to the extent that they considered it at all, they accepted

without question or an individual judgment, the ruling of the district

Under a compliance program now being established, periodic reviews of the

compliance status of all hospitals will be made.

In this regard, we have received your telegram dated July 19, 1966, indicat

ing that you have received reports that the Riverside Hospital has not acted

on applications from Negro doctors and that discrimination in room assign

ments is continuing. An appropriate investigation of these allegations has

been requested and you will be advised of the results as soon as they become

available.

court.

Sincerely

Deputy Special Assistant to the

Secretary for Civil Rights

15

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219