Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 2000

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 2000. 8a9e1597-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c995c07c-be2b-4572-ab75-e1e9260193c5/belk-v-charlotte-mecklenburg-board-of-education-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

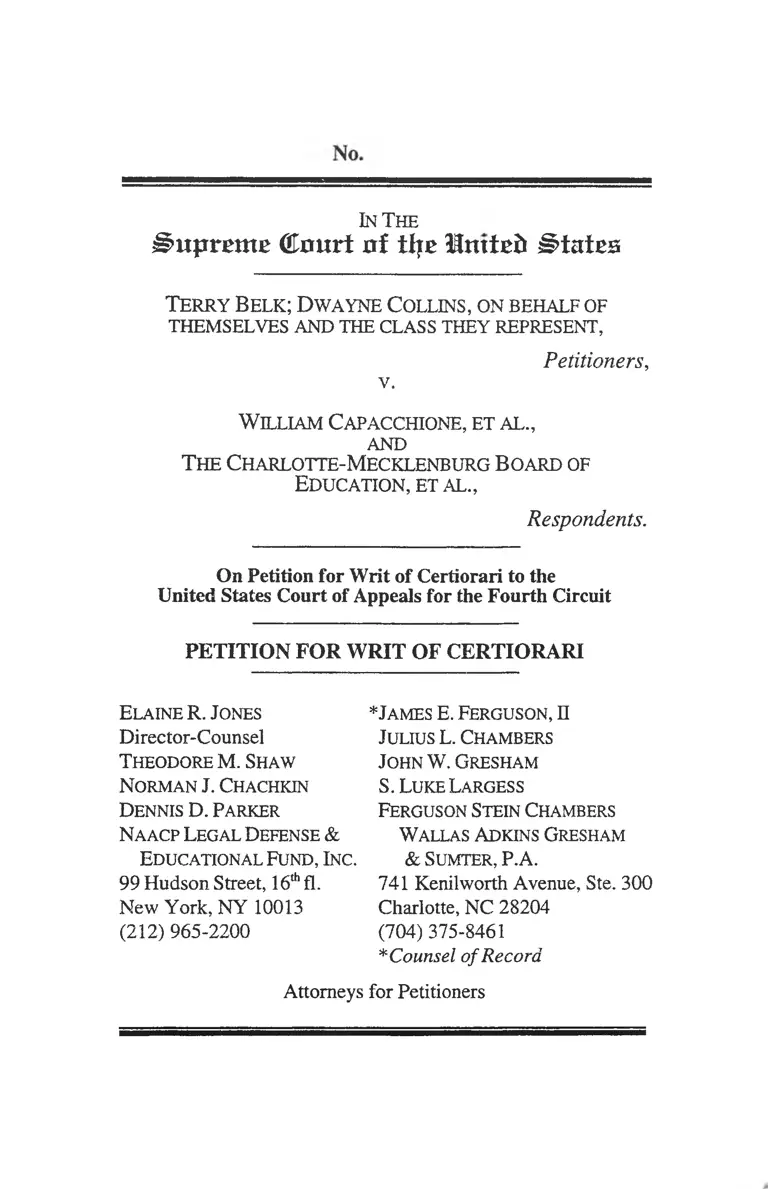

In The

Supreme Court of tfyr tlmteti Stairs

Terry Belk ; D w ayne C ollins, on behalf of

THEMSELVES AND THE CLASS THEY REPRESENT,

V.

Petitioners,

W illiam Capacchione, et a l .,

AND

T he Charlotte-Mecklenburg B oard of

Education , et al.,

Respondents.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Dennis D. Parker

Naacp Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

* James E. Ferguson, II

Julius L. Chambers

John W. Gresham

S. Luke Largess

Ferguson Stein Chambers

Wallas Adkins Gresham

& Sumter, P.A.

741 Kenilworth Avenue, Ste. 300

Charlotte, NC 28204

(704) 375-8461

* Counsel o f Record

Attorneys for Petitioners

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Did the courts below err when they determined that

the Charlotte school system had attained “unitary status”

despite the uncontested facts that:

(a) after operating largely integrated facilities for

more than a decade, the district in 1992 altered its

student assignment mechanism causing a dramatic

increase in the number of racially identifiable schools;

(b) the demographic changes in the school system (on

which the district court relied to explain and excuse

this resegregation) did not begin until the 1990’s, the

same time that the school system changed its method

of assignment;

(c) the school board built 25 of 27 new schools after

1979 in predominantly white suburban areas, in

violation of its own policy and the court’s express

orders on siting schools, with the result of

exacerbating the disproportionate burden of

transportation on black students that the district court

had identified in 1979 as a remaining vestige of prior

de jure segregation; and

(d) at the same time, the school board allowed the

condition of predominantly African-American, inner-

city school facilities to deteriorate rapidly?

2. Did the courts below err in applying an “intentional

discrimination” standard when determinating whether

persisting racial disparities (for example in the condition of

predominantly white and predominantly black schools) were

vestiges of the dual system whose continuation was

antithetical to the achievement of “unitary status”?

3. Did the courts below misconstrue and misapply

this Court’s decisions in Board ofEduc. v. Dowell, 498 U.S.

11

237 (1991) and Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467 (1992) in

determining that the Charlotte school system had attained

“unitary status” notwithstanding its consistent failure to

comply with the district courts’ remedial orders, with the

result that vestiges of the de jure segregation to which those

orders were addressed have not yet been eliminated?

4. Did the courts below err in refusing to consider a

remedial plan adopted by the school district after this case

was reactivated to finally address its continuing

constitutional responsibilities — a plan which demonstrated

the practicability of further desegregating its schools and

eliminating racial disparities in their operation — on the

grounds (stated by the district court) that the plan was only

“hypothetical” and objectionable because it proposed race

conscious assignments and (stated by the court of appeals)

that a unitary status inquiry does not require consideration of

remedial alternatives that remain available?

iii

LIST OF PARTIES

1. Karen Bentley, Respondent;

2. Terry Belk, Petitioner;

3. William Capacchione, Respondent;

4. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

Respondent;

5. Dwayne Collins, Petitioner;

6. Richard P. Easterling, Respondent;

7. Lawrence Gauvreau, Respondent;

8. Michael P. Grant, Respondent;

9. Arthur Griffin, Chairman of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

School Board, Respondent;

10. Eric Smith, Superintendent, in his official capacity,

Respondent;

11. Charles Thompson, Respondent;

12. Scott C. Willard, Respondent;

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW.................... i

PARTIES....... ............................................ iii

TABLE OF CASES................... ........................ .....................vi

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI....... .................................. 1

OPINIONS BELOW .............................................. 1

JURISDICTION................... 1

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION INVOLVED..................1

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS............................... 2

Initial Proceedings in the Litigation....................... ...2

Litigation Resumes; Problems Persist................................. 6

Major Student Assignment Changes Produce More

Racially Identifiable Schools................................................ 8

The Present Phase of the Case.................... ........... .......... 13

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT.......................... 15

I. The Court Below Ignored Basic Principles of

School Desegregation Jurisprudence Established by

this Court When It Affirmed the Unitary Status

Holding Despite the School Board’s Resegregative

Changes in Student Assignments and Its School

V

Location and School Repair and Maintenance

Practices....................................................................... 15

Changes in Pupil Assignment While Under Court Order.

..................................................... ....................... .................16

Demographic Change........................................................... IS

Location Of New Schools............................. 19

Deterioration Of Schools In Predominantly African-

American Areas.............................. 21

II. Contrary to Decisions of this Court, the Majority

Below Held That Racial Disparities in Various Areas

of the School District’s Operations Were Not

Vestiges of the Dual System Absent a Showing That

They Resulted from Intentional Discrimination......21

HI. The Court Below Departed From Established

Precedent In Declaring The Charlotte School District

Had Attained Unitary Status Without Requiring The

School District To Comply With Outstanding

Desegregation Orders..................................................23

IV. The Court Below Erroneously Sanctioned The

Trial Court’s Refusal To Consider The School

District’s Proposal For Eliminating The Vestiges Of

Segregation To The Extent Practicable................... 25

CONCLUSION 27

VI

TABLE OF CASES

Belk v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

233 F.3d 232 (4th Cir. 2000) (vacated)............................. 17

Belkv. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

21A F.3d 814 (4th Cir. 2001).............................................. 17

Belk v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

269 F.3d 305 (4th Cir. 2001)...................................... passim

Board ofEduc. o f Oklahoma City v. Dowell,

498 U.S. 237(1991)................................................... passim

Capacchione v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Board of Education,

57 F. Supp. 2d 228 (W.D.N.C. 1999)....................... passim

Columbus Bd. ofEduc. v. Penick,

443 U.S. 449 (1979).................................................... 22, 23

Dayton Bd. ofEduc. v. Brinkman,

443 U.S. 526 (1979)............................................................ 24

Dayton Bd. ofEduc. v. Brinkman,

433 U.S. 406 (1977)............................................................ 22

Freeman v. Pitts,

503 U.S. 467 (1992).................................................... passim

Green v. County School Bd. o f New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)..........................................6, 17, 23, 28

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1,

413 U.S. 189(1973).................................... ..........25

vii

Martin v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ.

475 F. Supp. 1318 (W.D.N.C. 1979).............. .......... passim

McDaniel v. Barresi,

402 U. S. 39(1971)............................................................ 28

North Carolina State Bd. o f Ed. v. Swann,

402 U. S. 43 (1971)............................................................ 28

Pasadena City Bd. o f Educ. v. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424 (1976)................................................... 20, 27

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

243 F. Supp. 667 (W.D.N.C. 1965)............................ 5, 22

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

300 F. Supp. 1381 (W.D.N.C. 1969).................. ................6

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

300 F. Supp. at 1372........................................................... 6

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

306 F. Supp. 1291 (W.D.N.C. 1969).................................. 6

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

306 F. Supp. 1299 (W.D.N.C. 1969).................................. 6

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

311 F. Supp. 265 (W.D.N.C. 1970).................. ..................6

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

318 F. Supp. 786 (W.D.N.C. 1970).................................... 7

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

328 F. Supp. 1346 (W.D.N.C. 1971) 7

viii

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

362 F. Supp. 1223 (W.D.N.C. 1973).............................. 7, 8

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

369 F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966).................................................. 5

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

379 F. Supp. 1102 (W.D.N.C. 1974).......................... . 8, 26

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

399 U.S. 926 (1970).............................................................7

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)............................. ...................... .7 , 22, 28

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

67 F.R.D. 648 (1975)............................................................ 9

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

334 F. Supp. 623 (W.D.N.C. 1971).....................................7

United States v. United Mine Workers,

330 U.S. 258 (1947)............... ............................................27

Walker v. City o f Birmingham,

388 U.S. 307 (1967)........................................................... 27

Wright v. Council o f City o f Emporia,

407 U.S. 451 (1972)........................ 24

1

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

Petitioners respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Belk, et al v. Charlotte

Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 269 F.3d 305.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, App. la-22 la,

is reported at 269 F.3d 305. The order of the Court of

Appeals on Rehearing, 382a-390a, is reported at 274 F.3d

814.The opinion of the District Court, 222a-367a, is reported

at 57 F. Supp. 2d 228. The order of the District Court of

April 14, 1999, 368a-376a, is unreported.

JURISDICTION

The Court of Appeals entered its judgment on

September 21, 2001, 377a-381a. On December 10, 2001, the

Chief Justice extended the time within which this Petition

may be filed to and including January 21, 2002, which falls

on a legal holiday. This Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION INVOLVED

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution provides in pertinent part that no state shall

“deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws”

2

STATEM ENT OF TH E FACTS

Terry Belk and Dwayne Collins petition for certiorari

from the September 21, 2001 decision of the en banc Fourth

Circuit Court of Appeals, Belk v. Charlotte Mecklenburg

Board o f Education, 269 F.3d 305 (4th Cir. 2001) (la-22 la )1,

affirming 7-4, the ruling of the district court below that the

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (“CMS” or “the

Board”) had attained unitary status in all respects.

Capacchione v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

57 F. Supp. 2d 228 (W.D.N.C. 1999) (222a-367a).

Initial Proceedings in the Litigation

Belk and Collins are substituted representatives for

those black families who originally filed this case in 1965 -

an initially unsuccessful challenge to a “freedom of choice”

pupil assignment plan that maintained racially segregated

schools. See 229a (citing to Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 243 F. Supp. 667

(W.D.N.C. 1965)). The district court upheld the plan in

1965, finding that the Board did not have an affirmative duty

to desegregate. Id. The Fourth Circuit affirmed. Swann,

369 F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966)

The plaintiffs moved for further relief in 1968 after

this Court, in Green v. County School Bd. o f New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), imposed on segregated school

systems an affirmative duty to desegregate. 229a. The trial

court found in April 1969 that approximately 14,000 black

students remained in segregated schools, 264a, and

concluded that the freedom of choice plan “had left the dual

school system virtually intact.” 23a, citing Swann, 300 F.

Supp. at 1372. The court ordered CMS to submit a plan to

1 Citations in the form “______ a” are to the Appendix to this

Petition, infra.

3

begin desegregation of the schools by the fall of 1969 and

suggested some methods for achieving that goal. 231a.

The “school board was slow to act on the court’s

recommendations” and was criticized by the court for “foot-

dragging.” 231a citing Swann, 300 F. Supp. 1381, 1382

(W.D.N.C. 1969). The district court approved an interim

plan in August 1969 but “expressed reservations that a

disproportionate burden of desegregation was being placed

on black children.” 231a (citing Swann, 306 F. Supp. 1291,

1298-99 (W.D.N.C. 1969)).

In November 1969, the court reviewed the

effectiveness of the plan and found it had “not been carried

out as advertised.” 231a, quoting Swann, 306 F. Supp. 1299,

1302 (W.D.N.C. 1969). The plan did not have definable

goals and did not safeguard against resegregation. Id. The

district court concluded that the Board had shown “no

intention to comply” with its constitutional duties, id.,

quoting Swann, 306 F. Supp. at 1306, and designated a

consultant, Dr. Finger, to draw up a plan. Id.

In February 1970 the Court adopted Dr. Finger’s

proposed plan for elementary schools and, with that

consultant’s modifications, a Board plan for secondary

schools. 232a, citing Swann, 311 F. Supp. 265, 268-70

(W.D.N.C. 1970). The plan transported students among

schools and paired grades from black and white elementary

schools to accomplish desegregation. 233a n.6. The Board

appealed, and the Fourth Circuit affirmed in part but

remanded the elementary school aspect of the plan. Belk,

12a.

This Court granted certiorari and reinstated the trial

court’s orders pending further proceedings. Capacchione,

233a, citing Swann, 399 U.S. 926 (1970). After additional

hearings, the trial court concluded that Dr. Finger’s plan was

4

reasonable. Id., citing Swann, 318 F. Supp. 786, 788

(W.D.N.C. 1970). This Court affirmed the orders, holding

that district courts could invoke their equitable powers to

fashion remedies to eliminate public school segregation.

234a - 235a (citing Swann, 402 U.S. 1 (1971)).

Within 60 days of this Court’s ruling, CMS moved in

the district court to abandon the Finger plan and permit the

substitution of a new “feeder” plan. Belk, 14a (citing

Swann, 328 F. Supp. 1346 (W.D.N.C. 1971)). Concerned

about resegregation and the placement of additional burdens

on African-American children, the district court openly

questioned the proposed feeder plan. Id., citing Swann, 328

F. Supp at 1350-53. The Board withdrew the plan and later

submitted a revised one that the court adopted. Id., citing

Swann, 334 F. Supp. 623 (W.D.N.C. 1971)). In accepting

the revised plan, the court “continued to express its

dissatisfaction with the regressive and unstable nature and

results” of the Board’s plans and actions. Capacchione,

235a, citing Swann, 328 F. Supp. 1346 and 334 F. Supp. 623.

The district court declined to hear any additional

matters until 1973, “in the hope that the board and its staff

would undertake constructive remedial action.” Id., citing

Swann, 362 F. Supp. 1223, 1230 (W.D.N.C. 1973). It did

not happen.

[Wjithin just two years it became clear that CMS’s

revised feeder plan was inadequate “for dealing with

foreseeable problems” in the dismantling of the dual

system. The district court found “that various

formerly black schools and other schools will turn

black under the feeder plan” and that “racial

discrimination through official action has not ended

in this school system.” The district court again

instmcted CMS to design a new pupil assignment

plan “on the premise that equal protection of the laws

5

is here to stay.”

Belk, 14a, quoting Swann, 362 F. Supp. at 1229, 1230, 1238

(W.D.N.C. 1973). The district court detailed the “signs of

continuing discrimination,” including the busing burden

placed on blacks, the pressures for resegregation created both

by the feeder plan and by the operation of overcrowded

white schools with mobile classrooms while historically

black schools had empty seats, and the “substantial immunity

from busing afforded to students in white areas in the east

and southeast of the county.” 362 F. Supp. at 1232-34.

In 1974 the Board adopted, and the court approved, a

new series of policies and guidelines for pupil assignment

that had originally been devised by a citizens’ group.

Capacchione, 235a - 236a; 15a, citing Swann, 379 F. Supp.

1102 (W.D.N.C. 1974). The district court called these new

policies a “clean break” from past practices and attitudes. “If

implemented according to their stated principles,” the

policies would result in a unitary school system.

Capacchione, 236a, quoting Swann, 379 F. Supp. at 1103.

The principles incorporated in the plan included avoiding

majority black schools (with one elementary school

experiment excepted), more equally distributing the busing

burden, and guidelines for transfers to prevent “adverse

trends in racial make-up of schools.” Id. (citing to 379 F.

Supp. 1104). See, also Belk, 15a (citing to 379 F. Supp. at

1105-1110). The principles also committed CMS to plan

school sites in order to simplify rather than to complicate

desegregation. Swann, 379 F. Supp. at 1104 (Guideline XI).

The district court’s 1974 order approved the creation

of “optional” schools with countywide enrollment.

Capacchione, 236a. The court approved these schools,

presently referred to as “magnet” schools, on the express

condition that they not become freedom of choice havens for

segregation or cause resegregation in any regular school. Id.

6

In 1975, noting that “continuing problems remain, as

hangovers from previous active discrimination,” the court

expressed a confidence that the Board would address those

problems, and placed the case on inactive status.

Capacchione, 236a, quoting Swann, 67 F.R.D. 648, 649

(W.D.N.C 1975)).

Litigation Resumes; Problems Persist

A few years later, the court found that many forms of

discrimination persisted. In 1978 a group of white parents

sued to end the use of race in assigning students and to block

a proposed reassignment. 240a (citing Martin v. Charlotte

Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ. 475 F. Supp. 1318 (W.D.N.C.

1979)). The Martin plaintiffs alleged that CMS was now

“unitary”, and thus any consideration of race in assigning

students was unconstitutional. Martin, 475 F. Supp. at 1322,

240a. Representative black families intervened in Martin,

and alleged that CMS was not yet unitary, pointing to non-

compliance with four aspects of the Swann orders - school

siting, placement of early elementary grades in black areas,

monitoring of student transfers to avoid resegregation, and

placing burdens unduly on black children. Martin, 475 F.

Supp. at 1328-29. In 1979 the same court that had decided

Swann heard the evidence in Martin, and “re-examined and

considered hundreds of pages of findings of facts and orders”

from Swann, and concluded that “jurisdiction was still

needed due to lingering effects from past active

discrimination.” 241a.

The court detailed at length the problems that

remained in the four areas. First it held that the

“CONSTRUCTION, LOCATION AND CLOSING OF

SCHOOL BUILDINGS CONTINUE TO PROMOTE

SEGREGATION.” Martin 475 F. Supp. at 1329 (caps in

original). The court reviewed several post-1974 siting

decisions by CMS. It noted that, contrary to its orders, CMS

7

had, after 1974, built new schools in white neighborhoods

and then bused black students into those schools to

desegregate them. It found these siting decisions violated

the principles approved by the court for the placement of

schools. Id. at 1331-1332.

It held next that the “PLACEMENT OF

KINDERGARTEN AND ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

GRADES REMAINS DISCRIMINATORY AND UNFAIR

TO THE SMALLEST BLACK CHILDREN.” Id. at 1332.

The court reviewed the fact that (with one exception) grades

K-3 in school pairings were located exclusively in schools in

white residential areas, leaving the busing burden entirely on

the youngest black children. Id. at 1332-1334.

The court next held that CMS’s “FAILURE TO

MONITOR THE THOUSANDS OF PUPIL TRANSFERS

. . . TENDS TO PROMOTE SEGREGATION IN THE

SCHOOLS.” Id. at 1335. The court found that CMS was

not effectively monitoring the transfers of students among

schools, which allowed transfers that cumulatively tended to

to make certain schools become racially identifiable. Id. at

1335-1338

Finally, the court found that the

“DISCRIMINATORY BURDENS OF DESEGREGATION

REMAIN UPON THE BLACK CHILDREN.” Id. at 1338.

The Court explained various ways in which CMS continued

to place the burdens of desegregation on black students, who

were bused on longer routes and for more years than white

students. Id. at 1338-1340. “In short, black children and

their families continue to bear discriminatory burdens of

desegregation.” Id. at 1340.

The court concluded that each of these four problem

areas was “interrelated with and not separable from . . . the

pupil assignment portion of the desegregation effort.” Id. at

8

1332, 1334, 1337 and 1340. As a result, “ ‘[rjacially neutral

attendance patterns’ have never been achieved.” Id. Despite

these findings, the court restated its belief that CMS was

committed to addressing the issues and concluded CMS

needed more time. “I vote to uphold their efforts to date, and

to give them that time.” Id at 1347.

By 1980 black enrollment in the school system had

reached 40%, Capacchione, 241a. The Board and the

Swann plaintiffs moved jointly to modify the court orders to

allow any elementary school to have a black enrollment up

to 15% above the system-wide ratio of black students. Id.

Notwithstanding the failures to fully implement the prior

orders described in detail in many of the Swann orders and in

Martin, CMS was able to keep most of its schools within

Swann’s racial balance guidelines in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

264a - 265a.

Major Student Assignment Changes Produce More

Racially Identifiable Schools

In 1992, with black enrollment still at 40%, CMS

undertook a major modification of pupil assignment - a plan

it called “A New Generation of Excellence”, 242a.2 The new

2 The population of Charlotte had increased substantially from

1970 to 1997, but the percentage of blacks living in the county remained

stable during this growth, increasing slightly from 24% in 1970 to 27%

in 1997. 237a. This period of overall growth with relative racial stability

was marked by the dispersion of blacks into suburban areas. 238a. A sa

result “there is a greater degree of residential integration in the county

than there was thirty years ago,” and “Charlotte has become one of the

most racially integrated cities in America.” Id. 238a.

At the time of the 1969 desegregation decrees, CMS enrolled

about 84,000 students, 239a. In the 1998-1999 school year, CMS had

98,542 pupils, id., an increase of about 14,500 students over 30 years.

While racial enrollments were unstable in the years immediately

following the desegregation orders, increasing from 29% black in 1969

to 40% in 1980, 241a, the percentage of black enrollment then stabilized.

9

assignment plan greatly expanded the use of the voluntary

optional or magnet schools and phased out the “unpopular”

mandatory pairing of schools from black and white areas.

242a. The plan also contemplated the increased use of

“stand alone” schools in integrated areas and schools in

“mid-point” areas with the stated goal of phasing out satellite

zones. 242a - 243a CMS took this major initiative without

seeking court approval. 243a

The trend toward resegregation of CMS’s schools

accelerated markedly following the decision to phase out

pairings. Belk, 152a (Motz and King, dissenting). From

1992 to 1998, the number of blacks in identifiably black

schools increased 50% system-wide, id., and nearly 200% at

the high school level, Stevens report, p. 21 (Fourth Circuit

JtApp. 9589). By 1998, some 30% of CMS’s African-

American students were attending racially identifiable

schools.3 Belk, 152a (Motz & King, dissenting). Twenty-

three schools were identifiably black at the time of trial. Id.

Twenty of those schools had been outside the court

guidelines for at least three consecutive years after 1992.

Capacchione, 57 F. Supp.2d at 248. Prior to the magnet

expansion and the end of pairing, CMS had been able to

maintain racial balance for periods of nineteen to twenty-six

years in nearly all of these schools. Belk, 28a (Motz &

King, dissenting).

In the 1998-99 school year, black enrollment was 42%. 239a.

Following a period of overall decline until 1990, student enrollment then

began growing by about 3,000 students per year. Id. Such growth was

not unprecedented, however: at the time of the original 1969 decrees,

CMS had been growing at a rate of 2,500 to 3,000 students per year.

Swann, 300 F. Supp. at 1358, 1364 (W.D.N.C. 1969).

3 Translated from percentages to numbers, over 12,000 black

students were in segregated schools in 1998-99, compared to 14,000 at

the time of the 1969 finding that CMS still operated segregated schools.

10

While deviations from target enrollment percentages

at schools in the 1970s had involved variances of “one or

two percent,” 265a, and only a “few” schools were

consistently out of balance in the 1980’s. Id. Both the

number of out-of-compliance schools and the extent of racial

identifiability increased substantially after 1992.

No CMS school had been as high as 60% black until

1988. 263a. “Only seven schools have ever had black

populations in excess of 75%, and this did not occur until

1994.” Id. The black population at six of those schools

jumped fifteen to twenty-five percentage points after

adoption of the new pupil assignment plan. Other schools

showed similar increases in racial identifiability after 1992.

The number of black students enrolled increased more than

20% at West Charlotte High School (from 46% to 68%),

Ranson Middle School (45% to 65%), Wilson Middle School

(45% to 71%), Coulwood Middle School (35% to 55%),

Merry Oaks Elementary (41% to 64%), Pawtuckett

Elementary (37% to 59%) and Greenway Park Elementary

(39% to 60%). CMS Ex. 47 (4th Cir. Jt. App. 13095 -

13099). Other schools’ imbalances increased in only

slightly less dramatic fashion, including Hawthorne Middle

School (36% to 53%), West Mecklenburg High School (38%

to 54%) and Garinger High School (49% to 61%), and the

following elementary schools, Oaklawn (45% to 63%),

Huntingtowne Farms (47% to 62%), Allenbrook (50% to

65%), Druid Hills (51% to 63%), Sedgefield (52% to 62%),

Shamrock Gardens (51% to 61%) and Statesville Road (48%

to 60%), Id.

The extent of identifiability increased at the

predominantly white schools as well. Prior to 1992-93, no

school had been 90% white; after 1992, there were eight

schools with 90% or more white enrollment. Id. More

generally, the schools with low black enrollments in 1999

11

that had been in operation since the 1970s had been racially

balanced for most of the period prior to the changes in pupil

assignment in 1992. Belk, 28a n.4 (Motz & King,

dissenting).

The Capacchione court identified a problem inherent

in numerous voluntary transfers under the magnet scheme.

“[I]f enough students left their assignment zones for

magnets, it would affect the balance of the schools to which

they were otherwise assigned.” 266a. Compare id. n. 23

(referring to overall impact of magnet schools’ operation but

not analyzing the Board’s failure to have “rigid controls in

place”). The resegregative impact of transfers of non-black

students away from indentifiably black schools to magnet

schools was significant. Data for 1998-99 from CMS Ex. 55

(4th Cir. Jt. App. 13165-13193) shows that at the middle

school level, 44.3% of the assigned non-black students

transferred away to magnets from four middle schools that

were at least 60% black, compared to a rate of 18.4% of non

blacks transferring to magnets from all other middle schools.

At the high school level 31% of non-blacks assigned to the

four high schools that were 50% or more black transferred

away to magnets, compared to 8.5% of non-blacks from the

remaining high schools.

The 1992 assignment plan also included the proposal

to increase the number of schools located “mid-point”

between racially distinct areas. Capacchione, 242a - 243a &

n.10. This proposal fit within the 1974 order, which held

that “[bjuildings are to be built where they can readily serve

both races.” 270a, quoting Swann, 379 F. Supp. at 1107.

The Martin court had found that CMS had yet to comply

with this aspect of the pupil assignment orders as of 1979,

Martin, 475 F. Supp. 1329-32. The Martin court specifically

criticized CMS for building schools in white residential areas

and then busing black students to them from distant areas.

12

CMS has built twenty-seven new schools since

Martin, see Capacchione, 271a. Twenty-five of them in

were located in predominantly white residential areas. Belk,

156a (Motz & King, dissenting). The “mid-point” approach

was applied in locating, “at most, four of the twenty-seven

new schools.” Id. The purpose of the mid-point policy was

to reduce the use of satellite zones. Capacchione, 242a -

243a. Because the mid-point policy was never applied,

“CMS has had to create dozens of tiny satellite zones in the

inner city” to assign black students to schools in white

neighborhoods. 247a. Thus, as student enrollment

increased, CMS coped with the situation by adding more

satellite zones for black students, assigning them to newly

built schools in white neighborhoods.

While the original court order in 1969 created nine

satellite zones, by 1998 there were sixty-nine. See, 280a,

citing CMS Exs. 262 - 264 (4th Cir. Jt. App. 1 5 4 1 1 -1 3 ).

The 1992 plan abolished the use of nearly all of the

“unpopular” satellite zones in white areas; instead one-way

satellites from black neighborhoods became the predominant

tool for desegregating schools. Sixty-three of the sixty-nine

satellites, or 91 percent, were located in black

neighborhoods. CMS Exs. 262 - 264. Of the 16,409

students assigned to schools by satellite, 14,957 lived in

predominantly black neighborhoods. Foster Report, Table 7.

CMS Trial Exhibits 262-64. Thus, while some of the new

schools “have been able to accommodate racially balanced

student populations,” Capacchione, 57 F.Supp. at 252, this

result could be achieved only by busing black children into

distant white neighborhoods.

In addition, disparities in facilities and resources

remain a serious problem. As CMS built new schools in

white areas, it allowed many of the older facilities, attended

predominantly by black students, “to fall into a state of

13

disrepair,” Belk, 156a (Motz & King, dissenting). The only

facilities expert to testify at the trial, Dr. Gardner, provided

numerical assessments of CMS schools showing

“substantial” racial disparities in the condition of facilities.

Id. at 166a - 168a. Numerous witnesses confirmed his

assessment of the problem. Id. at 168a - 169a.

Capacchione, 296a - 297a. Even the three Board members,

who had voted before the trial that CMS should seek unitary

status, each testified that the Board needed to address

disparities in facilities and resources in black schools. Id.

Belk, 169a (Motz & King, dissenting).

The Present Phase of the Case

In September 1997, William Capacchione, a white

parent, filed suit challenging the use of race in magnet school

admissions. Capacchione, 243a. In October 1997 the

Swann plaintiffs moved to reactivate Swann, alleging that

CMS was not in compliance with the court’s orders, and

moved to consolidate the two proceedings. 244a. In March

1998 the District Court denied a Board motion to dismiss the

Capacchione suit, granted the request to reactivate Swann,

and consolidated the two cases, finding that the issue of

unitary status was the common question between them. Id.

In May 1998, a separate group of white parents called the

Grant plaintiffs were allowed to intervene in the consolidated

action, claiming that the system was unitary and the use of

race in assigning students was unconstitutional. Id.

That same year, CMS undertook a “comprehensive

analysis” of its record of compliance, whether vestiges of

segregation existed and whether practicable remedial

measures could be taken. Belk, 146a - 147a (Motz & King,

dissenting). The Board then publicly adopted “The Charlotte

Mecklenburg Schools’ Remedial Plan to Address the

Remaining Vestiges of Segregation.” Id. The Remedial

14

Plan “detailed specific steps that the Board proposed to

undertake” to attain unitary status. Id.

The Board produced the plan as an exhibit for trial,

but the court granted a motion in limine to exclude it, finding

that the Court was required to review only “what CMS had

done, not what it may do in the future.” Order of April 14,

1999 (373a). Thus, the court refused to allow into evidence

any information on what practicable steps the Board could

take to remedy the increasing racial imbalances, to address

school siting and facilities issues, to relieve the unequal

transportation burdens and to address racial disparities in the

various Green factors and student achievement.

The court entered an order on September 9, 1999,

finding that CMS had attained unitary status in all respects

and that the magnet program’s application process was

unconstitutional. The court enjoined CMS from any

consideration of race in the future. The Fourth Circuit stayed

the injunction in an unpublished order. The en banc court

vacated a panel decision that had reversed the finding of

unitary status as to student assignment, transportation,

facilities and resources and student achievement. Belk v.

Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ., 233 F.3d 232 (4th Cir.

2000) (vacated). The en banc court then voted 7-4 to affirm

the unitary status determination, 6-5 to reverse the finding

that the school board acted unconstitutionally in adopting the

magnet plan while under court order, voted unanimously to

reverse as to the injunction, and voted 6-5 to reverse the

order awarding attorneys’ fees to Grant and Capacchione.

5a. The court then denied reconsideration of the attorney’s

fees’ issue. Belk, 21A F.3d 814 (4th Cir. 2001).

15

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I

The Court Below Ignored Basic Principles of

School Desegregation Jurisprudence Established by this

Court When It Affirmed the Unitary Status Holding

Despite the School Board’s Resegregative Changes in

Student Assignments and Its School Location and School

Repair and Maintenance Practices

This case presents fundamental legal questions under

this Court’s jurisprudence as to the conditions under which

previously de jure segregated school systems can attain

“unitary status” and be released from court supervision.

The court below ruled that CMS had attained unitary

status even though the district had changed its student

assignment policies without court approval, and then failed to

monitor the segregative effect of transfers under its new

assignment plan, both of which caused significant increases

in the number of racial identifiable schools and the extent of

segregation at those schools. From 1980 to 1997, the school

board had also built 25 of 27 new schools in white residential

areas while allowing existing schools in black areas to

deteriorate. The changes in pupil assignment, in conjunction

with the siting practices, fostered resegregation and

intensified the burdens placed upon black students in the

desegregation process.

These actions by CMS perpetuated or created classic

vestiges of segregation recognized by this Court’s precedent.

Nonetheless, the majority of the court of appeals found that

CMS had complied with the outstanding desegregation

orders and had eliminated the vestiges of segregation to the

extent practicable. This departure from settled principles

established by this Court, in a widely publicized case that

directly impacts the hundreds of school systems remaining

16

under court order, compels review of the judgment below.

Changes in Pupil Assignment While Under Court Order.

In 1992 CMS substantially modified its pupil

assignment policies without court approval. The system’s

previous student assignment plan had maintained

desegregation in “all but a few” of CMS’s schools until the

1992 revisions, notwithstanding population growth in the

county. The new student assignment plan rapidly phased out

the “unpopular,” court-approved system of mandatory pupil

assignment to racially paired elementary schools that “fed”

into assigned middle and high schools, replacing it with a

major expansion o f magnet schools. The board then failed to

monitor the resegregative effects of student transfers to this

increased number of magnet schools. Under the new plan,

the number of schools outside of racial enrollment

guidelines, and the levels of segregation at those schools,

increased dramatically, due both to the “de-pairing” of

previously paired schools and the impact of transfers.

CMS’s action modifying its student assignment

scheme while under a court desegregation order, in a manner

that increased the number of identifiably black schools and

the number of black students attending segregated schools,

distinguishes this case fundamentally from the two major

unitary status cases previously decided by this Court, Board

o f Educ. o f Oklahoma City v. Dowell, 498 U.S. 237 (1991)

and Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467 (1992). In neither of

those cases did the school board, knowing it remained under

court supervision, substantially modify its pupil assignment

plan in a manner that resegregated its schools.

Dowell. In Dowell, the school board had

implemented a court-ordered desegregation plan in 1972.

498 U.S. at 241. In 1977 the trial court declared the school

system “unitary” and ended active supervision of the case.

17

Id. Believing it was no longer under a desegregation order,

the Oklahoma City Board of Education adopted a student

reassignment plan (“SRP”) that significantly increased the

number of racially identifiable schools. Id., at 242. The

plaintiffs challenged the SRP as violating the court

injunction, which they asserted had never been lifted. This

Court concluded that because the 1977 order did not

explicitly vacate the earlier injunctive decrees, they remained

in effect. Id. at 244-45. However, the Court also found that

the school board had acted with a good faith belief that it

was no longer under court order when it adopted the SRP.

Id. at 249 n .l. Under those unique circumstances, the Court

remanded the case for a determination of whether the school

board had been entitled to a unitary status declaration in

1985 when it adopted the SRP, without considering the

decision to adopt the SRP or its effects on racial segregation

in the system. Id. at 249-50.

Because Dowell was decided in 1991, the year before

CMS modified its student assignment policies, CMS and its

staff fully understood that the district remained under the

court’s desegregation orders when it shifted to the expanded

magnet plan. (In fact, the magnet plan consultant advised

CMS to obtain court approval of the changes.) Thus, CMS’

decision to remake pupil assignment is wholly different from

the circumstances surrounding adoption of the SRP in

Dowell.

Freeman. The case is similarly distinct from

Freeman. First, this Court found that the DeKalb County

schools had implemented a court-approved desegregation

plan in 1969 that established race-neutral student

assignments and desegregated the schools before the process

was overwhelmed by dramatic changes in the racial

demographics of the county. 503 U.S. at 478-79. This Court

considered the attendance patterns established in DeKalb to

18

be “race-neutral” just as in Pasadena City Bd. o f Educ. v.

Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976). In Charlotte, however, the

trial court had ruled in 1979 that “racially neutral attendance

patterns have never been achieved,” in specific and detailed

distinction from Spangler. Martin, 475 F. Supp. at 1322-

24, 1340.

Second, the DeKalb County school system had not

changed its method of student assignment with segregative

results. Prior to its application for unitary status, the only

significant change in pupil assignment methods in Freeman

came in 1976, when the court ordered the DeKalb system to

expand its Majority-to-Minority (“M to M”) transfer

program, and when the DeKalb board introduced a small

number of magnet schools. 503 U.S. at 473,479.4

In CMS, the method of pupil assignment changed

fundamentally in 1992, with significant “resegregative

effect.” Those effects - sharp increases in the number of

racially identifiable schools and the extent of segregation at

those schools, caused by school board action - persisted at

the time of the district court’s hearing as vestiges of a

segregated school system.

Demographic Change

The court below distorted this Court’s ruling in

Freeman by applying it to CMS to hold that population

growth within Mecklenburg County over thirty years, rather

than the school board’s actions in 1992, explained the sharp

increases in segregation within the system from 1992 to

1999.

4 The trial court examined about 170 adjustments to attendance

zones made within the framework of the court- ordered plan and found

“only three had a partial resegregative effect.” Id.

19

However, comparisons between the changes in racial

demography in DeKalb and Mecklenburg counties show no

commonality. Black pupil enrollment in DeKalb shot up

from less than 6% in 1969 to 47% in 1986. 503 U.S. at 475.

In the ten years before the DeKalb school system applied for

unitary status, its overall elementary enrollment fell 15%, but

black elementary enrollment still increased 86%; overall

high school enrollment dropped 16%, while black high

school enrollment increased 119%. Id. at 476. These

dramatic changes resulted from an influx of tens of

thousands of black residents into the southern part of the

county and a commensurate exodus of whites that reshaped

the county into racially distinct poles. Id. at 475.

In contrast, the black population in Mecklenburg

County changed only from 24% in 1970 to 27% in 1997.

237a. Black student enrollment in CMS remained at a

constant 40% for the decade preceding CMS’s revisions to

student assignment in 1992. 239a. These stable racial

demographics coincided with increasing residential

integration in the community from 1970 to 1997. 238a.

Thus, CMS had maintained desegregation in all “but a few”

of its schools when it decided to revamp its student

assignment scheme. 265a.

The misapplication of Freeman’s acceptance of a

demographic explanation for resegregation to the markedly

different circumstances in CMS requires review and

correction by this Court.

Location Of New Schools

The courts below also misapplied this court’s

precedent in assessing the legal consequence of CMS’s

school siting decisions. This Court recognized in Swann

itself, involving this very school district, that building new

school facilities in predominantly white areas distant from

20

residential concentrations of minority students would “lock

in” patterns of segregation that typified the dual system. 402

U.S. at 20-21. In Columbus Bd. ofEduc. v. Penick, 443 U.S.

449, 460 (1979), the Court reiterated that formerly

segregated districts have an affirmative responsibility to

ensure that school construction practices “do not serve to

perpetuate or re-establish the dual school system.” The duty

applies to “the selection of sites for new school construction

that had the foreseeable and anticipated effect of maintaining

the racial separation of the schools.” Id. at 462. The

“failure or refusal to fulfill this affirmative duty continues

the violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.” Id. at 459

(citing Dayton Bd. ofEduc. v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406, 413-

14 (1977) and other cases). In affirming the trial court’s

“unitary status” holding, the Fourth Circuit ignored these

fundamental principles.

Despite marginally higher rates of growth in the

school-age population in black residential areas from 1980 to

the time of trial, CMS located 25 of 27 new schools in white

residential areas, accelerating resegregation when CMS

changed its pupil assignment methods in 1992 and putting

the burden of desegregating those new schools almost

entirely upon black children. Instead of locating schools in

areas midway between racially distinct areas, CMS built

schools in predominantly white areas and transported black

pupils there to achieve some degree of desegregation in those

new schools. This directly ignored the district court’s

directives in Swann, which required CMS to locate schools

in places readily accessible to both races and to lessen the

burdens placed on black families by desegregation. See

Martin, 475 F. Supp. at 1329-1332; 1338-1340.

This case accordingly presents important questions

about the continuing vitality of the principles established in

Swann and Penick that this Court should resolve.

21

Deterioration Of Schools In Predominantly African-

American Areas

The impact of building new schools in white

residential areas upon the racial identifiability of the

district’s schools was compounded by the Board’s failure to

adequately maintain and provide resources in the schools

located in the black residential areas. Racial disparities in

the facilities of a formerly dual school system have long

been recognized as a vestige of the segregated system.

Green v. County School Bd. o f New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430, 435 (1968). The courts below, contrary to this Court’s

precedent, found that these disparities in facilities (and in

resources) were not vestiges of desegregation because they

had not been shown to be the result of intentional

discrimination by the board. 40a. See Argument II infra.

II

Contrary to Decisions of this Court, the Majority

Below Held That Racial Disparities in Various Areas of

the School District’s Operations Were Not Vestiges o f the

Dual System Absent a Showing That They Resulted from

Intentional Discrimination

In Dayton Bd. o f Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526,

538 (1979), this Court stated clearly that “the measure of the

post -Brown I conduct of a school board under an unsatisfied

duty to liquidate a dual system is the effectiveness, not the

purpose, of the actions in decreasing or increasing the

segregation caused by the dual system.” (citing Wright v.

Council o f City o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 460, 462 (1972)

and other cases).

Nevertheless, in assessing whether racial disparities

in school siting, burdens of transportation, and the quality of

facilities located in white or black residential areas that

existed at the time of trial were vestiges of the prior dual

22

system, the majority below incorrectly applied an intentional

discrimination standard. E.g., 33a (“CMS never sited

schools in order to foster segregation.”); 34a (“The evidence

does not indicate that the abandonment of the ten percent

rule or other decisions regarding school siting were the result

of a desire to perpetuate the dual system or circumvent the

district court’s orders,”); 40a (district court “concluded that

any disparity as to the condition of the facilities [in black and

white neighborhoods] that might exist was not caused by any

intentional discrimination by CMS,” a finding that “is clearly

determinative of the question of unitary status as to

facilities.”); 35a (considering burdens of busing and

approving “district court’s conclusion that the realities of the

current situation should not block a unitary status

determination” even though the “current realities” to which

district court referred were the location of new schools in

white areas and the creation of numerous inner-city satellites

from which black pupils were transported, 273a-274a, school

district practices to which the courts below applied an

intentional discrimination standard).

The emphasis of the majority of the court of appeals

on the necessity to show post-1970's intentional

discrimination to establish that current disparities are

vestiges of the prior dual system is contrary to the

controlling decisions of this Court. It had two related

effects, moreover that require review and reversal of the

judgment below: first, it removed the presumption

applicable in de jure school segregation cases that ongoing

racial disparities in the operation of the schools are causally

related to the dual system; second, it shifted the burden of

proof from those seeking to end the district court’s

jurisdiction - the party moving for unitary status - to the

original plaintiffs. Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S.

189,207-211 (1973).

23

III

The Court Below Departed From Established

Precedent In Declaring The Charlotte School District

Had Attained Unitary Status Without Requiring The

School District To Comply With Outstanding

Desegregation Orders.

Under Dowell and Freeman, a school district must

demonstrate compliance with the outstanding orders of the

court before it can be released from court supervision. See,

e.g., Freeman, 503 U.S. at 492. Yet the courts below

declared that CMS had attained unitary status even though

the history of the case and the trial record showed that the

system had never complied with express orders designed to

further desegregation. Certiorari should be granted to review

and reverse this stark departure from this Court’s standards

for determining unitary status.

From 1969 until 1973 the Board repeatedly

challenged the district court’s authority to order

desegregation, and the court entered numerous specific

orders to accomplish that result. In 1974, the Board adopted

guidelines for desegregation that the court embraced as a

break from the Board’s previous attitude, with the caveat that

the principles must be implemented to end the litigation.

The court was emphatic:

The future depends upon the implementation of the

new guidelines and policies. This approval is

expressly contingent upon the implementation and

carrying out of all the stated policies and guidelines.

Here is the heart of the matter. Only if they are thus

implemented is it likely that a fair and stable school

operation will occur, and that the court can close the

case.

24

Swann, 379 F. Supp. at 1103. In 1979, the same judge ruled

in Martin that the Swann orders, including the guidelines

from 1974, had not been implemented in specific areas. The

facts from the trial record showed, and the school board

admitted, that CMS had not, since Martin, complied with the

prior orders regarding the location of new schools, the

monitoring of student transfers to prevent resegregation, and

the balancing of the burdens of desegregation. Despite the

undisputed facts of non-compliance in these areas, the courts

below declared that CMS had attained unitary status.

The courts below reconciled this record of non-

compliance by dismissing the significance of Martin. The

courts found the “concerns” of that case had no relevance to

the unitary status inquiry because Martin had not itself been

a unitary status hearing. The court of appeals declared that

consideration of CMS’s continued non-compliance with the

Swann orders as outlined in Martin “would defy common

sense and run afoul of developments in the Supreme Court’s

school desegregation jurisprudence.” Belk, at 32a.5 That

holding, however, is flatly inconsistent with Freeman’s

requirement that a school board must demonstrate its

“commitment to the entirety of a desegregation plan” in

order to attain unitary status, 503 U.S. at 498. The school

board must show that compliance with all orders entered in

the desegregation case, not just selective acquiescence with

some. See Dowell, 498 U.S. at 249-50. (“The District Court

should address itself to whether the Board has complied in

good faith with the desegregation decree since it was

entered, and whether the vestiges of past discrimination had

been eliminated to the extent possible) (emphasis supplied);

Pasadena City Bd. ofEduc. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 437-

The dissent in the court of appeals found the findings in

Martin “are as binding on the parties as any others made in the course of

this litigation.” Belk. at 155a, n. 10 (Motz and King dissenting).

25

40 (1976) (until modified or vacated by court with authority

to do so, injunctive decrees must be obeyed even if they

contain provisions contrary to rulings issued by this Court

subsequent to their entry), citing Walker v. City o f

Birmingham, 388 U.S. 307 (1967) and United States v.

United Mine Workers, 330 U.S. 258 (1947). That reasoning

of the court of appeals misapprehends the holdings in

Freeman and Dowell and requires review and reversal by

this Court.

IV

The Court Below Erroneously Sanctioned The

Trial Court’s Refusal To Consider The School District’s

Proposal For Eliminating The Vestiges Of Segregation

To The Extent Practicable

The heart of the Dowell/Freeman test is that a

formerly segregated school district must eliminate the

vestiges of segregation to the extent practicable. Courts have

long recognized the primacy and importance of allowing

local school boards to determine in the first instance what

measures might most effectively and practicably accomplish

its constitutional obligations. The school district here made

just such a determination by adopting and submitting to the

court a remedial plan with specific proposals for complying

with the orders of the court and eliminating the vestiges of

discrimination within a specified period of time.

The district court not only refused to consider the

Board’s plan; it refused to even allow it into evidence, thus

completely ignoring the most probative and relevant

evidence on the question of eliminating the vestiges and

ignoring the strong and long tradition of federal courts’

deferring to local school board efforts to desegregate local

schools. This Court recognized that tradition in its decision

in this case:

26

Remedial judicial authority does not put judges

automatically in the shoes of school authorites whose

powers are plenary. Judicial authority enters only

when local authority defaults. School authorities are

traditionally charged with broad power to formulate

and implement educational policy.

Swann, 402 U.S. at 16. It was only after the school

authorities repeatedly defaulted in their obligation to develop

a plan in the original case that Judge McMillan adopted a

plan developed by a court appointed consultant.

The ultimate rationale for the district court’s refusal

to admit and consider the Board’s remedial plan was the

court’s objection to “the plan’s cardinal fixation on racial

preferences”, 279a-283a. Of course, however, a

desegregation plan must take race into account. See North

Carolina State Bd. o f Ed. v. Swann, 402 U. S. 43 (1971);

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U. S. 39 (1971). The court

rejected the plan because it did what a desegregation plan is

supposed to do — take race into account.

The majority below affirmed the district court’s

refusal to consider the plan, although it did not adopt the

district court’s rationale. Nonetheless, the rationale adopted

by the majority is likewise flawed. The majority’s statement

that Freeman and Dowell do not mandate consideration of

the remedial plan in determining the issue of vestiges (53 a-

55a) signals a fundamental misreading of those cases.

Freeman and Dowell, as well as Green, do mandate

consideration of the Board’s plan because the plan

demonstrates that there is more that the Board can

practicably do to eliminate the vestiges. There is simply

nothing in any of those cases that supports or suggests that a

plan developed by the school board and offered as a

demonstration that continuing racial disparities linked to the

27

original dual system can be eliminated or reduced can or

should be ignored by the court.

The majority’s alternative rationale, that the refusal

constitutes harmless error, is equally flawed, if not more so.

The majority looked at the plan, although the plan was not

made a part of the record nor analyzed by the district court,

and pronounced it both duplicative of other evidence (54a)

and “short on specifics” (55a). This approach flagrantly

confuses the appropriate roles of trial and appellate courts

and warrants the exercise of this Court’s supervisory

authority over lower federal courts.

On its face, the plan is powerfully probative on the

important student assignment issues in the case. The district

court and the court below excused continued racially

identifiable schools on the grounds that demographics and

logistics required construction of most new schools in white

suburbs and limited the extent to which (at least white)

pupils could be transported for desegregation purposes. The

CMS “controlled choice” plan at least offered a realistic

promise of substantially reducing the level of racial isolation

and identifiability at many schools without engaging in

logistically impossible transportation or creating greater

reassignment burdens. Surely it should have been evaluated

on the record by the trial court rather than ignored. To find

unitary status without even assessing its promise through the

adversary process and formal findings that can be properly

reviewed by an appellate court makes a mockery of the

careful instructions about unitary status determinations this

Court gave in Dowell and Freeman.

CONCLUSION

In Dowell and Freeman this Court established the

parameters for ending court supervision of formerly de jure

school systems. The case below, widely followed in its trial

28

and appellate phases, particularly by the hundreds of school

systems that remain under court supervision, greatly distorts

and even inverts the standards established by this Court. The

decisions below, left unreviewed, promise the nation an end

to school desegregation decrees even where a school district

has taken actions that resegregate its schools, where it has

not complied with outstanding orders of the court and where

tangible vestiges of segregation exist. The practical steps a

district knows it could take to comply with the prior orders

and eliminate the persisting unresolved racial disparities in

the operation of its schools will be irrelevant. A board's

failure to meet its affirmative constitutional duties under a

desegregation order will be excused simply if that failure

was not intentional. The burden will now be on the black

plaintiffs to show not that tangible vestiges of the de jure era

still persist, but to prove that those continuing disparities are

the result of new, intentional discrimination. Such a result is

a complete and dramatic departure from this Court’s school

desegregation precedent and compels this Court’s review.

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Dennis D. Parker

Naacp Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, NY 10013

(212-965-2200)

* James E. Ferguson, II

Julius L. Chambers

John W. Gresham

S. Luke Largess

Ferguson Stein Chambers

Wallas Adkins Gresham

& Sumter, P.A.

741 Kenilworth Ave., Ste. 300

Charlotte, NC 28204

(704) 375-8461

* Counsel o f Record

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

1

I N D E X

Page

Opinions o f the Court of Appeals

of September 21, 2001 .......................... ...................la

Opinion o f the District Court

o f September 9, 1999 .......................... ................. 222a

Order o f the District Court

o f April 14, 1999 .................................................. 368a

Judgment of the Court o f Appeals

o f September 21, 2001 ......................................... 377a

Order of the Court of Appeals on Rehearing

of December 14, 2001 ......................................... 382a

la

Opinions o f the Court o f Appeals o f September 21, 2001

United States Court of Appeals,

Fourth Circuit.

Terry BELK; Dwayne Collins, on behalf of themselves and

the class they represent, Plaintiffs-Appellants,

William Capacchione, Individually and on behalf of

Christina Capacchione, a minor; Michael P. Grant; Richard

Easterling; Lawrence Gauvreau; Karen Bentley; Charles

Thompson; Scott C. Willard, Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

The CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF

EDUCATION; Eric Smith, Superintendent, in his official

capacity; Arthur Griffin, Chairman of the Charlotte-

Mecklenburg School Board,in his official capacity,

Defendants.

United States of America; North Carolina School Boards

Association; National School Boards Association,

Amici Curiae.

William Capacchione, Individually and on behalf of

Christina Capacchione, a minor; Michael P. Grant; Richard

Easterling; Lawrence Gauvreau; Karen Bentley; Charles

Thompson; Scott C. Willard, Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

Terry Belk; Dwayne Collins, on behalf of themselves and

the class they represent, Plaintiffs,

v.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education; Eric Smith,

Superintendent, in his official capacity; Arthur Griffin,

Chairman of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board, in his

official capacity, Defendants-Appellants.

2a

Opinions o f the Court o f Appeals o f September 21, 2001

United States o f America; North Carolina School Boards

Association; National School Boards Association,

Amici Curiae.

William Capacchione, Individually and on behalf of

Christina Capacchione, a minor; Michael P. Grant; Richard

Easterling; Lawrence Gauvreau; Karen Bentley; Charles

Thompson; Scott C. Willard, Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

Terry Belk; Dwayne Collins, on behalf o f themselves and

the class they represent, Plaintiffs,

v.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education; Eric Smith,

Superintendent, in his official capacity; Arthur Griffin,

Chairman of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board, in his

official capacity, Defendants-Appellants.

United States of America; North Carolina School Boards

Association; National School Boards Association,

Amici Curiae.

William Capacchione, Individually and on behalf of

Christina Capacchione, a minor; Michael P. Grant; Richard

Easterling; Lawrence Gauvreau; Karen Bentley; Charles

Thompson; Scott C. Willard, Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

Terry Belk; Dwayne Collins, on behalf of themselves and

the class they represent, Plaintiffs,

v.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education; Eric Smith,

Superintendent, in his official capacity; Arthur Griffin,

Chairman of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board, in his

official capacity, Defendants-Appellants.

$

3a

Opinions o f the Court o f Appeals o f September 21, 2001

United States of America; North Carolina School Boards

Association; National School Boards Association,

Amici Curiae.

Nos. 99-2389, 99-2391, 00-1098 and 00-1432.

Argued Feb. 27, 2001.

Decided Sept. 21, 2001

[269 F.3d 305]

*310 ARGUED: Stephen Luke Largess, James Elliot

Ferguson, II, Ferguson, Stein, Wallas, Adkins, Gresham &

Sumter, P.A., Charlotte, NC; John W. Borkowski, Hogan &

Hartson, L.L.P., Washington, DC, for Appellants. Allan Lee

Parks, Parks, Chesin & Miller, P.C., Atlanta, GA, for

Appellees. ON BRIEF: John W. Gresham, C. Margaret

Errington, Ferguson, Stein, Wallas, Adkins, Gresham &

Sumter, P.A., Charlotte, NC; Elaine R. Jones,

Director-Counsel, Norman J. Chachkin, Gloria J. Browne,

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., New York,

NY; Allen R. Snyder, Maree Sneed, Hogan & Hartson, L.L.P.,

Washington, DC; James G. Middlebrooks, Irving M. Brenner,

Amy Rickner Langdon, Smith, Helms, Mulliss & Moore,

L.L.P., Charlotte, NC; Leslie Winner, General Counsel,

Charlotte- Mecklenburg Board of Education, Charlotte, NC, for

Appellants. Kevin V. Parsons, Parks, Chesin & Miller, P.C.,

Atlanta, GA; John O. Pollard, McGuire, Woods, Battle &

Boothe, Charlotte, NC; William S. Helfand, Magenheim,

Bateman, Robinson, Wrotenbery & Helfand, Houston, TX;

Thomas J. Ashcraft, Charlotte, NC, for Appellees. Bill Lann

Lee, Acting Assistant Attorney General, Mark L. Gross,

Rebecca K. Troth, United States Department of Justice,

4a

Opinions o f the Court o f Appeals o f September 21, 2001

Washington, DC, for Amicus Curiae United States. Michael

Crowell, LisaLukasik, Tharrington Smith, L.L.P., Raleigh,NC;

Allison B. Schafer, General Counsel, North Carolina School

Boards Association, Raleigh, NC; Julie K. Underwood,

General Counsel, National School Boards Association,

Alexandria, VA, for Amici Curiae Associations.

*311 Before WILKINSON, Chief Judge, and WIDENER,

WILKINS, NIEMEYER, LUTTIG, WILLIAMS, MICHAEL,

MOTZ, TRAXLER, KING, and GREGORY, Circuit Judges.

Affirmed in part and reversed in part by published opinions.

A per curiam opinion announced the judgment of the court.

Judge TRAXLER delivered the opinion of the court with

respect to Parts I, II, IV, and V, in which Chief Judge

W ILKINSON and Judges WIDENER, WILKINS,

NIEMEYER, and WILLIAMS joined, and an opinion with

respect to Parts III and VI, in which Judges WILKINS and

WILLIAMS joined. Chief Judge WILKINSON wrote an

opinion concurring in part in which Judge NIEMEYER joined.

Judge WIDENER wrote an opinion concurring in part and

dissenting in part. Judge LUTTIG wrote an opinion concurring

in the judgment in part and dissenting from the judgment in

part. Judges MOTZ and KING wrote a separate opinion in

which Judges MICHAEL and GREGORY joined.

OPINION

PER CURIAM:

This case was argued before the en banc Court on

February 27, 2001. The parties presented a number of issues

5a

Opinions o f the Court o f Appeals o f September 21, 2001

for our consideration, including whether the district court erred

in (1) finding that unitary status had been achieved and

awarding attorneys' fees to plaintiff-intervenors based on this

find ing; (2) holding that the establishment of a magnet schools

pro g ram was an ultra vires, unconstitutional act justifying an

award of nominal damages and attorneys' fees; (3) enjoining

the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board from considering race

in the future assignment of students or allocation of educational

resources; and (4) sanctioning the Board for failing to comply

with the district court's discovery order.

Having considered the briefs and arguments of the

parties, a majority of the Court holds: (1) by a 7-4 vote (Chief

Judge Wilkinson and Judges Widener, Wilkins, Niemeyer,

Luttig, Williams and Traxler in the affirmative), the school

system has achieved unitary status, but by a 6-5 vote (Chief

Judge Wilkinson and Judges Niemeyer, Michael, Motz, King

and Gregory in the affirmative) attorneys' fees for work done on

the unitary status issue are denied; (2) by a 6-5 vote (Chief

Judge Wilkinson and Judges Niemeyer, Michael, Motz, King,

and Gregory in the affirmative), the Board did not forfeit its

immunity for the establishment of the magnet schools program,

and nominal damages and attorneys' fees in that regard are

denied; (3) by a unanimous vote, the injunction is vacated;

and (4) by a unanimous vote, the imposition of sanctions is

affirmed.

The judgment of the district court is therefore affirmed

on the finding of unitary status and the imposition of sanctions,

reversed as to the finding of liability for nominal damages for

the establishment of the magnet schools program, reversed as

to the imposition of attorneys' fees for any reason, and reversed

on the issuance of the injunction.

6a

Opinions o f the Court o f Appeals o f September 21, 2001

Unitary status having been achieved, the judgment of

the district court vacating and dissolving all prior injunctive

orders and decrees is affirmed. The Board is to operate the

school system without the strictures o f these decrees no later

than the 2002-2003 school year.

AFFIRMED IN PART AND REVERSED IN PART.

TRAXLER, Circuit Judge:

This case is hopefully the final chapter in the saga of

federal court control over the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools

("CMS"). Since 1971 CMS has operated under a federally

supervised desegregation plan that included limited use of

racial ratios, pairing and grouping o f school zones, and

extensive busing. So successful was the plan that the district

court removed the case from the active docket in 1975,

expressing its belief that the once reluctant school board was

committed to achieving desegregation and was already *312

well on the way toward a unitary school system. Since then,

two generations of students have passed through CMS and,

until the present case, not one person has returned to court

alleging that segregative practices have been continued or

revived.

Now, nearly three decades later and prompted by a

lawsuit filed by a white student challenging the magnet schools

admissions policy, the question o f whether CMS has achieved

unitary status has been placed before our courts. In 1999, the

district court, after a lengthy hearing and searching inquiry,

concluded that CMS had indeed achieved unitary status by

eliminating the vestiges of past discrimination to the extent

7a

Opinions o f the Court o f Appeals o f September 21, 2001

practicable. This conclusion was not reached in haste; it was

the result of a two-month hearing and an examination of

extensive testimony and evidence relating to every aspect of

CMS's educational system.

A majority of this court now affirms the district court's

holding on this issue, satisfied that CMS has dismantled the

dual school system. In sharp contrast to the situation in the late

1960s, when black students were segregated in black schools

and taught by a predominantly black staff, CMS students today

are educated in an integrated environment by an integrated

faculty. Nor do we turn over control to an indecisive and

uncommitted school board. CMS currently operates under the

firm guidance of an integrated school board which has clearly

demonstrated its commitment to a desegregated school system.

In sum, the "end purpose" of federal intervention to

remedy segregation has been served, and it is time to complete

the task with which we were charged—to show confidence in

those who have achieved this success and to restore to state and