Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on Detroit-Only Plans of Desegregation

Public Court Documents

March 28, 1972

7 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on Detroit-Only Plans of Desegregation, 1972. 8e204325-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c99e7982-d4ad-4cf8-a3dd-e5b28176bd16/findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law-on-detroit-only-plans-of-desegregation. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

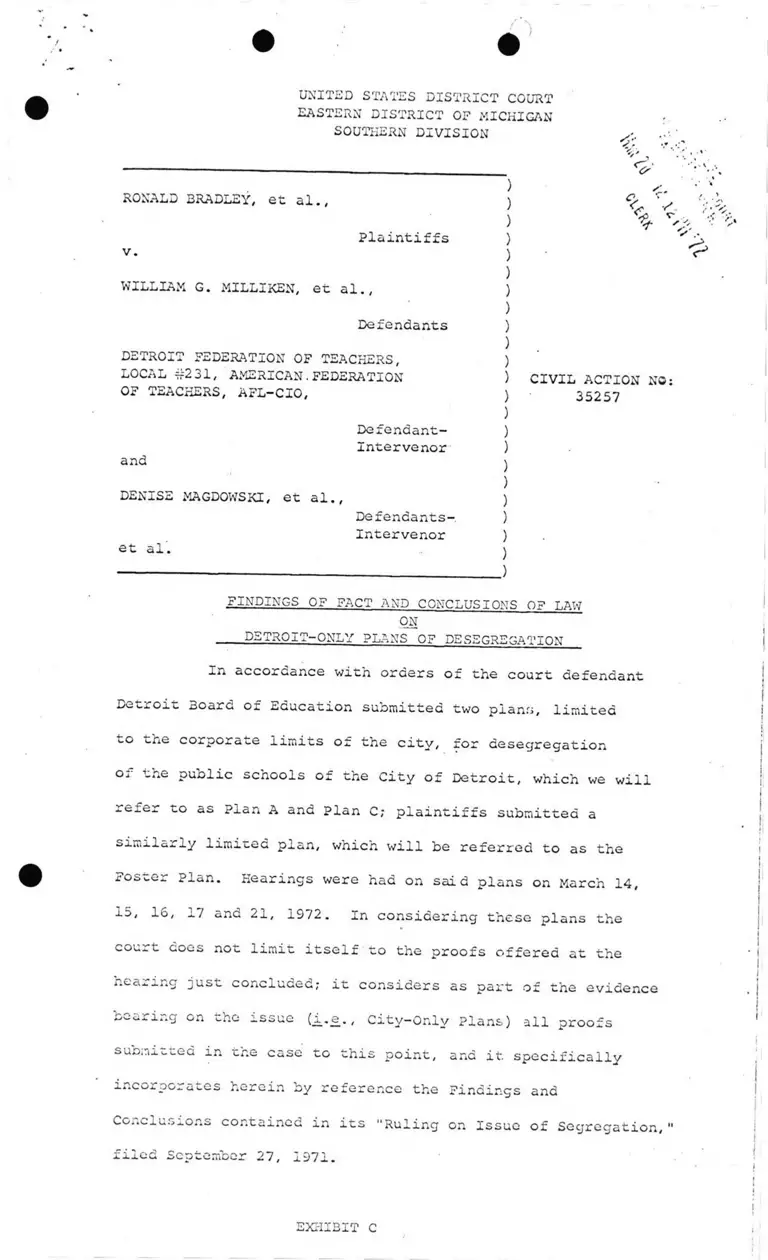

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffsv.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN.FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-

Intervenorand

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendants

Intervenoret al. ..

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

% ' %

CIVIL ACTION NO:

35257

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

ON

. DETROIT-ONLY PLANS OF DESEGREGATION

1^ accordance with orders of the court defendant

Detroit Board of Education submitted two plans, limited

'-O the corporate limits or the city, for desegregation

of the public schools of the city of Detroit, which we will

refer to as Plan A and plan C; plaintiffs submitted a

similarly limited plan, which will be referred to as the

Foster Plan. Hearings were had on said plans on March 14,

x5, 16, 17 and 21, 1972. In considering these plans the

court coos not limit itself to the proofs offered at the

heading just concluded; it considers as part of the evidence

bearing on the issue (_i. e. , City-Only Plans) all proofs

submitted in the case to this point, and it specifically

incorporates herein by reference the Findings and

Conclusions contained in its "Ruling on Issue of Segregation, 11

filed September 27, 1971.

EXHIBIT C

The court makes the following factual findings.-

PLAN A .

1. The court finds that this plan is an elabora

tion and extension of the so-called Magnet Plan, previously

authorized for implementation as an interim plan pending

hearing and determination on the issue of segregation.

2. As proposed we find, at the high .school level,

that it offers a greater and wider degree of specialization,

but any hope that it would be effective to desegregate the

public schools of the City of Detroit at that level is

virtually ruled out by the failure of the current model to ■

achieve any appreciable success. .

3. We find, at the Middle school level, that the

expanded model would affect, directly, about 24,000 pupils

of a total of 140,000 in the grades covered; and its effect

would be to' set up a school system within the school system,

and would intensify the segregation in schools not included

in the Middle School program. In this_sense, it would

increase segregation.

4. As conceded by its author, Plan A is neither a

desegregation nor an integration plan.

PLAN C.

1. The court finds that Plan C is a token or part

time desegregation effort.

2. We find that ahis plan covers only a portion

of the grades and would leave the base schools no less

racially identifiable.

- 2 -

PLAINTIFFS‘ PLAN.

1. The court finds that Plaintiffs' Plan would

accomplish more desegregation than now obtains in the system, '

or would be achieved under plan A or Plan C.

\

2'. ̂ We find further that the racial composition of

the student body is such that the plan's implementation would

clearly make the entire Detroit public school system

racially identifiable as Black.

3. The plan would require the development of trans

portation on a vast scale which, according to the evidence,

could not be furnished, ready for operation, by the opening -

or the 1972-73 school year. The plan contemplates the

transportation of 82,000 pupils and would require the

acquisition of some 900 vehicles, the hiring and training

of a great number of drivers, the procurement of space

for srorage and maintenance, the recruitment of maintenance personnel

and the not negligible task of designing a transportation

system to service the schools.

4. The plan would entail an overall recasting

or the Detroit school system, when there is little assurance

that it would not have to undergo another reorganization if

a metropolitan plan is adopted.

5. It would involve the expenditure of vast sums

or money and effort which would be wasted or lost.

6. The plan does not lend itself as a building

block for a metropolitan plan.

7. The plan would make the Detroit school system

more identifiably Black, and leave many of its schools 75 to ■

- 3 -

90 per cent Black.

8. It would change a school system which is now

Black and White to one that would be perceived as Black,

thereby increasing the flight of Whites from the city and

the system, thereby increasing the Black student population.

9. It would subject the students and parents,

faculty and administration, to the trauma of reassignments,

with little likelihood that such reassignments would

continue for any appreciable time.

In summary, we find that none of the three plans

would result in the desegregation of the public schools of

the Detroit school district.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. The court has continuing jurisdiction of this

action for all purposes, including the granting of effective

relief. ■ See Ruling on Issue of Segregation, September 27,

1971.

2. On the basis of the court's finding of illegal

school segregation, the obligation of the school defendants

is to adopt and implement an educationally sound, practicable

plan of desegregation that promises realistically to achieve

now and hereafter the greatest possible degree of actual

school desegregation. Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S.

430; Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S.

19; Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S.

290; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1.

- 4 -

3. Detroit Board of Education Plans A and C

«re legally insufficient because they do not promise to

effect significant desegregation. Green v. County School

Board, supra, at 439-440.

^ • Plaintiffs' Plan, while it would provide a

racial mix more in keeping with the Black-White proportions

of the student population than under either of the Board's

plans or as the system now stands, would accentuate the

racial identifiability of the district as a Black school

system, and would not accomplish desegregation.

5. ihe conclusion, under the evidence in this

case, is inescapable that relief of segregation in the

public schools or the Crty of Detroit cannot be accomplished

within the corporate geographical limits of the city. The

Sf-a-t-e. hnwAver,. cannot escape its constitutional duty to

desegregate the public schools of the City of Detroit by

pleaaing locai authority. As Judge Merhige pointed out

Bradley v. Richmond, (slip opinion p. 64):

"The power conferred by state law on central and

local officials to determine the shape of school

attendance units cannot be employed, as it has been

here, zor the purpose and with the effect of sealing

off white conclaves of a racial composition more

appealing to the local electorate and obstructing the

desegregation of schools. The equal protection

clause has required far greater inroads on local

government structure than the relief sought here,

which is attainable without deviating from state *

statutory forms. Compare Reynolds v. Sims, 377 u.S.

_<3~>, Gomillion v. Ligntfoou, 364 U.S. 339; Serrano v.

Priest, 40 U.S.L.W. 2128 (Calif. Sup. Ct. Aug. 30, 1971)

"In any case, if political boundaries amount to

insuperable obstacles to desegregation because of

structural reason, such obszacles are self-imposed.

Political subdivision lines are creations of the state

itself, after all."

- 5 -

School district lines axe simply matters of

political convenience and may not be used to deny

constitutional rights. If the boundary lines of the

school districts of the city of Detroit and the surround

ing suburbs were drawn today few would doubt that they

could not withstand constitutional challenge. In seeking

for solutions to the problem of school segregation, other

federal courts have not "treated as immune from intervention

the administrative structure of a state's educational

system, no the extent that it affects the capacity to

desegregate. Geographically or administratively independent

units have been compelled to merge or to inititate or

continue cooperative operation as.a single system for school

desegregation purposes."1

xhau i_he court must look oeyond the limits of the

iX2troiu school district for a solution to the problem of

segregation in the Detroit public schools is obvious;

'■hat it has the authority, nay more, the duty to (under

tne circumstances of this case) do so appears plainly

anricipatied by Brown II,2 seventeen years ago. While other

school cases have not had to deal with our exact

■ _ • 3situation, the logic of their application of the command

of Brown II supports our view of our duty.

.onc" •

Date: MARCH ^ 0 , 1972. .

- 6-

r

.1

FOOTNOTES

1Bradley v. Richmond, supra (slip opinion p. 68).

Brown'v. Bd. of Ed. of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294, pp. 300-301.

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County,

410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969); Bradley v. School Board of the

City of Richmond, supra, slip opinion pp. 664-65; Hall v.

St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp. 649 (E.D. La.

1961), affd. 287 F.2d 376 (5th Cir. 1961) and 368 U.S. 515

(1962); Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 746, 752

(5th Cir. 1971); Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960);

Turner v. Lirtleton-Lake Gaston School Dist., 442 F.2d 584

(4th Cir. 1971); United States v. Texas, 447 F.2d 551

(5th Cir. 1971); Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 446 .

F.2d 911 (5th Cir. 1971).

r