Richards v Vera Appeal Appendix to Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

September 22, 1994

91 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Richards v Vera Appeal Appendix to Jurisdictional Statement, 1994. 0e45a031-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c9d52bf7-b061-42c9-ba4b-83705b3fd419/richards-v-vera-appeal-appendix-to-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

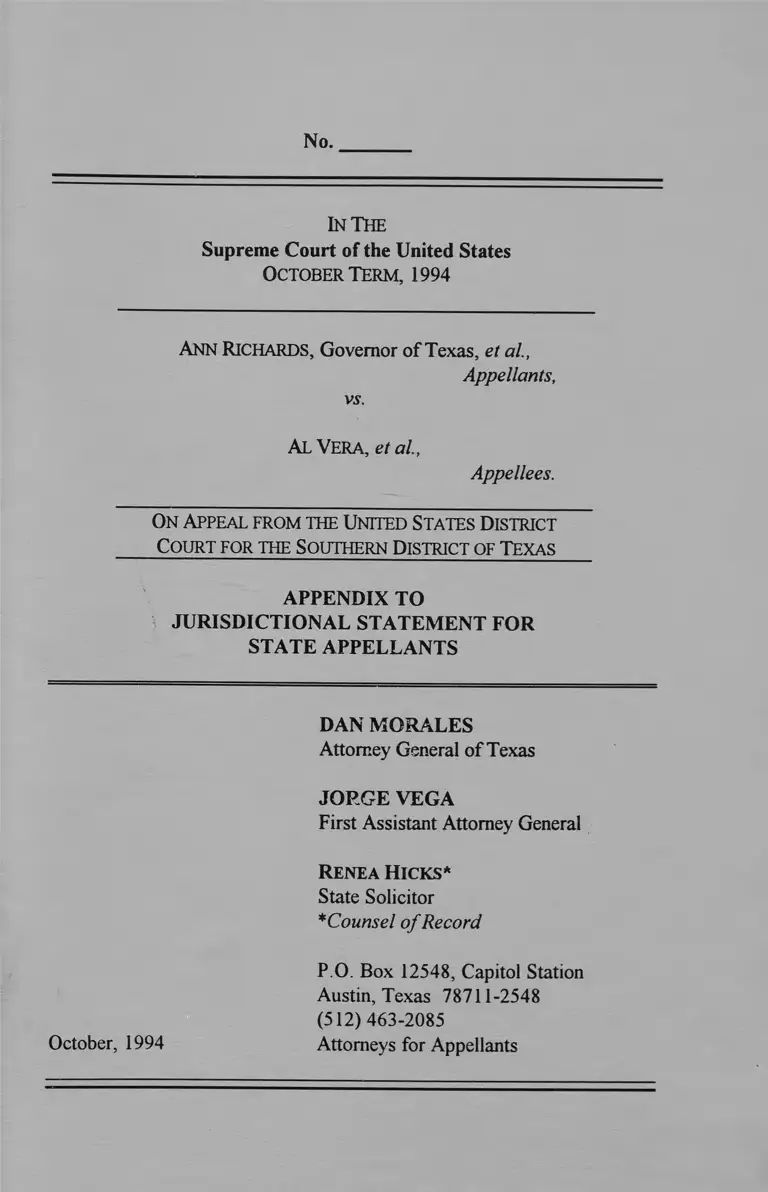

No.

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1994

ANN RICHARDS, G overnor o f T exas, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

Al Vera, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Texas

APPENDIX TO

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT FOR

STATE APPELLANTS

DAN MORALES

Attorney General of Texas

JORGE VEGA

First Assistant Attorney General

Renea Hicks* *

State Solicitor

* Counsel o f Record

P.O. Box 12548, Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711-2548

(512) 463-2085

October, 1994 Attorneys for Appellants

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS - APPENDIX

Page(s)

Order, September 2, 1994 ...................................... la

Amended Order, September 20, 1994 ......................... 3a

Opinion, August 17, 1994 ............................................ 5a

Notice of Appeal, September 22, 1994 ....................... 85a

Voting Rights Act (Sections 2 and 5) ........................... 87a

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

HOUSTON DIVISION

Filed September 2, 1994

AL VERA, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

ANN RICHARDS, et al„

Defendants,

v.

REV. WILLIAM LAWSON,

et al.,

Defendant-Intervenors,

v.

UNITED STATES OF

AMERICA,

Defendant-Intervenor,

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN

AMERICAN CITIZENS

(LULAC) OF TEXAS, et al.,

Defendant-Intervenors.

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§ C.A. No. H-94-0277

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

2a

ORDER

This court has carefully reviewed the briefs and submissions of

parties pertaining to the question of relief from the unconstitutional

Congressional districts created by the state of Texas, and, based upon

the applicable law and the facts as represented to this court, it is

hereby:

ORDERED

1. That the fall 1994 Congressional elections for the state of

Texas shall proceed according to the districts created by the 1991 plan

C657;

2. that the Texas legislature shall develop on or before March

15, 1995, a new Congressional redistricting plan in conformity with

this court’s previous opinion during the 1995 regular legislative

session that convenes on January 10, 1995;

3. that on or shortly after March 5, 1995, this court will hold a

remedial hearing on the status of the legislature’s redistricting efforts;

4. that plaintiffs shall submit their application for attorneys

fees and costs within 30 days of the date hereof; and

5. that all other relief sought by the parties in their post-trial

submissions on relief is denied.

SIGNED at Houston, Texas, on this the 2nd day of September

1994.

_____________ /§/_________________

EDITH H. JONES

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT JUDGES

_____________ IsL_________________

DAVID HITTNER

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

Is/

MELINDA HARMON

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

3a

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

HOUSTON DIVISION

Filed September 20, 1994

AL VERA, et al., §

§

Plaintiffs, §

§

v - §

§

ANN RICHARDS, et al., §

§

Defendants, §

v.

REV. WILLIAM LAWSON,

et al.,

Defendant-Intervenors,

v.

UNITED STATES OF

AMERICA,

Defendant-Intervenor,

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN

AMERICAN CITIZENS

(LULAC) OF TEXAS, et al.,

Defendant-Intervenors.

§

§

§

§

§

§ C.A. No. H-94-0277

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

4a

AMENDED ORDER

This court has considered the state’s Unopposed, Emergency

Motion for Expedited Entry of Explicit Injunction, and, finding it

well-grounded, it is hereby:

ORDERED that the state’s Unopposed, Emergency Motion for

Expedited Entry of Explicit Injunction is GRANTED; it is further

ordered that:

The Court’s Order entered September 2, 1994, is hereby

amended nunc pro tunc to provide as additional relief that the state

defendants, their officers and assigns, and all those in active concert

or participation with them are hereby enjoined from conducting

(including opening candidate qualifying) the 1996 Congressional

elections for the state of Texas according to the districts created by

the 1991 plan C657.

SIGNED in Houston, Texas, on this the 19th day of

September, 1994.

_____________ /§/_________________

EDITH H. JONES

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT JUDGES

____________Is/_______________

DAVID HITTNER

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

Is/

MELINDA HARMON

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

5a

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

HOUSTON DIVISION

Filed August 17, 1994

AL VERA, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

ANN RICHARDS, et al.,

Defendants,

v.

REV. WILLIAM LAWSON,

et al.,

Defendant-Intervenors,

v.

UNITED STATES OF

AMERICA,

Defendant-Intervenor,

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN

AMERICAN CITIZENS

(LULAC) OF TEXAS, et al.,

Defendant-Intervenors.

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§ C.A. No. H-94-0277

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

6a

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Introduction .................................................. 1

II. Procedural History ........................................ 5

III. Evidentiary Background .............................. 8

A. Texas Demography Related to Redistricting 8

B. Pertinent History Related to Redistricting

in Texas ............................................... 11

C. The 1991 Congressional Redistricting

Process ............................................... 13

1. General Background .............. 13

2. Voting Rights Act Considerations 17

a. Racial Polarization 20

b. History of Discrimination 22

3. Incumbents’ Interests ........ 23

4. Use of Racial Data .......... 25

5. Congressional District 30 ... 27

6. Congressional Districts 18 and 29 37

7. Congressional District 28 ... 43

8. Other Congressional Districts 46

D. Expert Testimony .............................. 51

E. Other Districting Plans .................. 55

IV. Factual Findings and Legal Conclusions .... 57

A. The Voting Rights District ......... 72

2. Congressional District ......... 78

3. Narrow Tailoring to Achieve a Compelling

State Interest? ...................... 84

4. Congressional District 28 89

B. Other Congressional Districts ....... 90

V. Conclusion 92

Special Concurrence ..............................

Appendix (Maps of Districts 18, 29, 30)

7a

OPINION

Before JONES, Circuit Judge, HITTNER and HARMON, District

Judges. EDITH H. JONES, Circuit Judge:

I. INTRODUCTION

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 at one blow demolished the

obvious devices that southern states had used to disenfranchise

African-American voters for decades. The Act marked the full

maturity in American political life of the Founders’ idea that ‘'all men

are created equal” and the Rev. Martin Luther King’s hope that his

children would be judged by the content of their character, not the

color of their skin. The meaning of equality — as also enshrined in the

Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of “equal protection of the laws” -

- is the subject of this lawsuit.

It is no longer disputed that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments embody a right to ballot box equality among American

citizens of different races or ethnic backgrounds. See, e.g., Rodgers v.

Lodge. 458 U.S. 613 (1982); Baker v. Carr. 369 U S. 186 (1962);

Gomillion v, Lightfoot. 364 U.S. 339 (1960). The Fourteenth

Amendment also prohibits government from invidiously classifying

persons because of their race. Repeatedly and in the strongest terms,

the Supreme Court has condemned intentional racial discrimination by

state agents or bodies. Where official discrimination is found to exist,

the burden is on the governmental body to justify it by no less than a

compelling governmental interest.

One year ago, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that intentional

racial discrimination is offensive to the Equal Protection Clause when

it occurs as part of legislative redistricting. See Shaw v. Reno. 113

S.Ct. 2816 (1993). In Shaw, the Court held that “redistricting

legislation [is unconstitutional if it] is so extremely irregular on its

face that it rationally can be viewed only as an effort to segregate the

races for purposes of voting, without regard for traditional districting

principles and without sufficiently compelling justification.” Id. at

2824.

In 1991, the State of Texas deliberately redrew its

Congressional boundary lines following the 1990 census with nearly

exact knowledge of the racial makeup of every inhabited block of land

8a

in the state. This insight, worthy of Orwell’s Big Brother, was

attainable because computer technology, made available since the last

decennial census, superimposed at a touch of the keyboard block-by

block racial census statistics upon the detailed local maps vital to the

redistricting process. Not only did the state know the precise location

of African-American, Hispanic, and Anglo populations, but it

repeatedly segregated those populations by race to further the

prospects of incumbent officeholders or to create ‘fnajority-minority”

Congressional districts. The result of the Legislature’s efforts is

House Bill 1 (‘HB1’), a crazy-quilt of districts that more closely

resembles a Modigliani painting than the work of public-spirited

representatives.1

The challenged plan (HB1) was passed in the second called

session of the 72nd Texas Legislature and signed into law by the

Governor on August 29, 1991. See Plaintiff Exh. 1. On November

18, 1991, the Texas Congressional Redistricting Plan received § 5

preclearance from the Attorney General.2 See United States Exh.

1007; Stip. 37. Notwithstanding the preclearance, the Attorney

General expressed fundamental reservations about the redistricting

plan:

While we are preclearing this plan under Section 5, the

extraordinarily convoluted nature of some districts

compels me to disclaim any implication that the

proposed plan is otherwise lawful or constitutional.

United States Exh. 1007 at 2.

The plaintiffs in this case are six Texas voters who reside in

Congressional Districts 18, 25, 29, and 30. In a pretrial stipulation,

HB1 will alternatively be referred to as Plan C657, the plan number

assigned by the State’s redistricting software to the plan embodied in HB1.

As Texas is covered by § 5 of the Voting Rights Act, the Legislature must

either (1) have any proposed plan precleared by the Department of Justice, or (2)

seek a judgment from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia

declaring that the plan "does not have the purpose and will not have the effect of

denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race or color. . . . " Voting

Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c.

9a

they alleged that 24 of the state’s 30 Congressional Districts are the

product of racial gerrymandering or intentional racial discrimination.3

The question before this court is whether any of the 24

challenged Congressional Districts, many of whose boundaries were

clearly affected by racial considerations, can be sufficiently explained

by legitimate redistricting criteria other than race. See Shaw. 113

S.Ct. at 2824. For reasons that follow, we conclude that

Congressional Districts 18, 29, and 30 as presently drawn are not so

explainable. They were conceived for the purpose of providing “safe”

seats in Congress for two African-American and an Hispanic

representatives. They were scientifically designed to muster a

minimum percentage of the favored minority or ethnic group, minority

numbers are virtually all that mattered in the shape of those districts.

Those districts consequently bear the odious imprint of racial

apartheid, and districts that intermesh with them are necessarily

racially tainted.

Other challenged Texas Congressional Districts are disfigured4

less to favor or disadvantage one race or ethnic group than to promote

the reelection of incumbents; they are not unconstitutionally

segregated.

We do not hold that the state may only draw Congressional

boundaries with a blind eye toward race, a goal which would be

impossible, nor that it is altogether prohibited from creating majority-

minority districts. But when the State redraws the boundaries of

Districts 18, 29, and 30 and contiguous districts, it can and must

exhibit respect for neighborhoods, communities, and political

subdivision lines. As the Supreme Court put it, appearances do

matter. In appearance and in reality, these three districts were racially

gerrymandered.

Racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional, but it is also morally

wrong, inconsistent with our founding tradition and Martin Luther

King’s vision. The color of a person’s skin or his or her ethnic

identity is the least meaningful way in which to understand that

The plaintiffs’ post-trial submissions seem to suggest that they now

challenge ah 30 districts, but we reject this belated attempt to broaden the scope

of the case.

To call these districts “configured” in any sense that implies order would

be a misnomer.

10a

person. To elevate racial classification as a basis for political

representation inevitably defeats the principle of equality because it

causes all of society to become more, not less, race-conscious. Justice

William O. Douglas put this point well:

When racial or religious lines are drawn by the State,

the multiracial, multireligious communities that our

Constitution seeks to weld together as one become

separatist; antagonisms that relate to race or to

religion rather than to political issues are generated;

communities seek not the best representative but the

best racial or religious partisan. Since that system is

at war with the democratic ideal, it should find no

footing here.

Wright v. Rockefeller. 376 U.S. 52, 67 (1964) (Douglas, J.,

dissenting) (quoted in Shaw. 113 S.Ct. at 2827).

II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY

The plaintiffs are six registered voters who reside in

Congressional Districts 18, 25, and 29 (located in whole or in part in

Harris County), and in District 30 (most of which is located in Dallas

County). See Complaint at 4 |̂7. Plaintiffs filed their Original

Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Declaratory Judgment and

Motion for Preliminary Injunction on January 26, 1994 against the

Governor, the Lieutenant Governor, the Attorney General, and the

Secretary of State as well as the Speaker of the Texas House of

Representatives.

The complaint alleged that the 1991 Congressional Redistricting

Plan for the State of Texas ‘Yepresents an unconstitutional effort to

segregate the races for purposes of voting: (1) without regard for

traditional districting principles, including compactness,

contiguousness [sic], consistency with existing political, economic,

societal, governmental or jurisdictional boundaries; (2) without

sufficiently compelling justification; and (3) without ‘narrow

11a

tailoring’ as required by the United States Constitution.” Complaint

at 2 HI.5

Candidate qualifying for the March 8, 1994 primary elections in

Texas closed on January 3, 1994 and early voting began on February

16. On March 2, 1994, the court entered an order denying the

plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction and their motion for

consolidation and expedited hearing and set trial for June 28, 1994.

Also on March 2, 1994, the court granted the motion of the United

States to participate as amicus curiae in the case. On March 14,

1994, the state defendants in this action filed their answer to the

complaint.

On May 5, 1994, the court granted the motion to intervene of six

African-American registered voters represented by the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (‘Lawson Intervenors’). On May

20, 1994, the court granted the motion of the United States to

intervene. A week later, on May 27, 1994, the court entered an order

granting intervention to both The League of United Latin American

Citizens (‘LULAC’) and seven Hispanic registered voter members of

the organization.

On June 13, 1994, the United States filed a motion to bifurcate

trial; the court denied the motion on June 17, 1994. On June 16,

1994, the court conducted the pretrial conference. At the pretrial

conference, the court set the pretrial schedule and directed the

plaintiffs to file a statement narrowing the districts to which they

asserted challenges and eliminating any claims not supported by

substantial evidence or case law. In response, on June 16, 1994, the

plaintiffs filed a statement dismissing their § 26 and state

constitutional claims and identifying six districts that they did not

challenge under the Fourteenth Amendment. In a subsequent filing,

the plaintiffs dismissed their Fifteenth Amendment claims.7 Trial was

held June 27-30 and concluded on July 1, 1994.

In addition to their claim under the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, the plaintiffs alleged that the 1991 Congressional

Redistricting Plan violated the Fifth and Fifteenth Amendments, as well as the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973. Complaint at 14 U 39-

6 Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973.

As delineated in their June 16th specification, the plaintiffs challenge

twenty districts as unconstitutional racial gerrymanders under the framework of

12a

To expedite matters, this court limited the parties’ trial time

while permitting them to submit virtually unlimited additional

documentary and deposition evidence. The parties liberally accepted

this offer.8 The court has reviewed all of the evidence brought before

us. The record references below highlight and summarize the

testimony.

III. EVIDENTIARY BACKGROUND

A. Texas Demography Related to Redistricting

Congressional redistricting in Texas operated against a

backdrop of important demographic changes throughout the state.

Population growth from 1980 to 1990 was largely attributable to

significant population growth among Hispanics and African-

Americans. Of particular interest is the enormous increase in

Hispanic population state-wide. Thus, what follows are the Census

figures chronicling minority-led population growth in Texas during the

1980’s.

According to the 1980 Census, Texas’ total population was

14,229,191, of whom 2,985,824 (20.98%) were Hispanic, 1,692,542

(11.89%) were non-Hispanic African-American, and 9,350,297

(65.7%) were Anglo. See Stip. 7. By the 1990 Census, Texas’ total

population had increased to 16,986,510, of whom 4,339,905 (22.55%)

were Hispanic, 1,976,360 (11.63%) were non-Hispanic African-

American, and 10,291,680 (60.59%) were Anglo. The increase in

population from 1980 to 1990 (2,757,319 persons) entitled Texas to

three additional seats in the United States House of Representatives, * 13

Shaw v, Reno. 113 S.Ct. 2816 (1993). The targeted districts are Districts 3-9, 12-

13, 18-19, 21-26, and 28-30. Four additional districts — Districts 1, 2, 14, and 15 -

- were challenged; under Hays v. Louisiana (Hays I), 839 F.Supp. 1188 (W.D. La.

1993) . The Supreme Court vacated the judgment in Hays I and remanded the case

to the district court for further consideration in light of the Louisiana Legislature’s

repeal of Act 42 and creation of a new districting scheme in Act 1. See Louisiana

v. Hays, 62 U.S.L.W. 3859 (June 27, 1994). After a two-day trial, the district court

once again struck down the Louisiana redistricting plan as an unconstitutional

racial gerrymander. See Hays v, Louisiana (Hays II), No. 92-1522 (W.D. La.

1994) . The court adopted by reference its opinion in Havs I. See id. at 2. This

court finds it unnecessary, to determine whether, as the parties argue, Havs I goes

beyond Shaw.

The parties, however, chose not to use all of their allotted trial time.

13a

increasing the size of the delegation from 27 to 30. See Stip. 8. Based

on the 1990 Census, the ideal size of a Texas Congressional district is

566,217. See Stip. 17.

Under the 1980 Census, Texas’ voting-age population was

9,923,085, of whom 1,756,971 (17.71%) were Hispanic, 1,095,836

(11.04%) were non-Hispanic African-Anerican, and 6,932,894

(69.87%) were Anglo. See Stip. 9. By 1990, Texas’ voting-age

population had increased to 12,150,671, of whom 2,719,586 (22.38%)

were Hispanic, 1,336,688 (11.0%) were non-Hispanic African-

American, and 7,828,352 (64.43%) were Anglo. See Stip. 10.

Taking citizenship into account alters these percentages. Under 1990

figures, the total citizen voting age population is only 11,313,641, of

whom 2,085,857 (18.4%) were Hispanic, and 1,315,860 (11.6%) were

non-Hispanic African-American. See State Exh. 14, Appendix 1.

Even a cursory review of the foregoing Census data reveals the

significant growth experienced by minority communities, and, in

particular, the explosive population growth among Hispanics in

Texas. The Hispanic population in the state grew from 1980 to 1990

by 1,354,081 persons, or 45.4%; the African-American population in

the state grew from 1980 to 1990 by 283,818 persons, or 16.8%; and

the Anglo population in the state grew from 1980 to 1990 by 941,383

persons, or 10.1%. The growth in Hispanic population accounted for

a remarkable 49.1% of the increase in Texas’ total population from

1980 to 1990. See Stip. 11.

The four counties with the largest growth in population from

1980 to 1990 in number of persons gained are Harris, Tarrant, Dallas,

and Bexar Counties. As noted below, the growth in the Hispanic and

African-American population in these counties accounted for a

significant proportion of the increase in population in each of these

counties:

a. The total population of Harris County increased by

408,652 persons from 1980 to 1990. The Hispanic

population in the county increased by 275,858 persons,

accounting for 67.5% of the growth in total population

in the county. The African-American population

increased by 58,674 persons, accounting for 14.4% of

the county’s growth. See Stip. 12. According to the

1990 Census, there are 644,935 Hispanic persons in

14a

Harris County, of whom 405,735 are of voting age. See

Stip. 13. Furthermore, there are 527,964 African-

American persons in the county, of whom 359,248 are

of voting age. See Stip. 14.

b. The total population of Tarrant County increased by

309,223 persons from 1980 to 1990. The Hispanic

population in Tarrant County increased by 72,247

persons, accounting for 23.4% of the growth in total

population in the county. The African-American

population in Tarrant County increased by 37,765

persons, accounting for 12.2% of the county’s growth.

See Stip. 12.

c. The total population of Dallas County increased by

296,420 persons from 1980 to 1990. The Hispanic

population in the county increased by 161,069 persons,

accounting for 54% of the growth in the total population

of the county. The African-American population

increased by 76,343 persons, accounting for 25.8% of

the county’s growth. See Stip. 12. In Dallas County,

there are 362,130 African-American persons of whom

243,918 are of voting age. See Stip. 15.

d. The total population of Bexar County increased by

196,594 persons from 1980 to 1990. The Hispanic

population in Bexar County increased by 128,269

persons, accounting for 65.2% of the growth in the total

population of the county. The African-American

population in Bexar County increased by 13,326

persons, accounting for 6.8% of the county’s growth.

See Stip. 12.

Significant increases in Hispanic population occurred

between 1980 and 1990 in several other counties:

a. The Hispanic population of Cameron County increased

by 51,341 persons between 1980 and 1990.

b. The Hispanic population of Hidalgo County increased

by 96,760 persons between 1980 and 1990.

c. The Hispanic population of Webb County increased by

34,227 persons between 1980 and 1990.

See Stip. 16.

15a

B. Pertinent History Related to Redistricting in Texas

Texas did not redistrict Congressional Districts at all between

1933 and 1957. See United States Exh. 1071 at 7. Following the

1960 Census, the state ‘Yedistricted” by creating a new at-large

Congressional seat. See State Exh. 23, |6 . This approach to

redistricting allowed all incumbents’ existing districts to remain intact

and meant that the at-large candidate had to campaign across and

represent the entire state. Also in the 1960’s, Texas created the now

infamous District 6 — often known as ‘Tiger” Teague’s district —

which ran from Fort Bend County through rural east Texas into the

southern ends of both Tarrant and Dallas Counties. See State Exh.

41.

The 1971 round of Congressional redistricting was notable at

least in part because of the great lengths to which the state legislature

went to solicit the views of incumbent congressmen. The Senate

Congressional Redistricting Subcommittee actually flew to

Washington to meet with the Texas delegation as a group and on an

individual basis.9 See State Exh. 23, f8. In the 1980’s, the Texas

Legislature managed to put together a plan despite two novel facts —

the first Republican governor elected in Texas since Reconstruction

and the applicability of § 5 of the Voting Rights Act to Texas

Congressional redistricting. See United States Exh. 1071 at 14;

Plaintiff Exh. 28A (Map of 1980’s Plan C001).

Ted Lyon, a former member of the Texas House and Senate involved in

the 1980 and 1990 redistricting battles, asserted that “[CJompactness is not a

traditional districting principle’ in Texas. For the most part, the only traditional

districting principles that have ever operated here are that incumbents are

protected and each party grabs as much as it can. There is no reason why the State

should now have to draw compact majority-minority districts when it has shown no

interest over the years in drawing compact majority-white districts.” Lawson Exh.

14, 117; see id. at Tf 12 (“Neither pretty districts nor compact districts are a

priority in Texas, and they have not been since well before I was involved in

districting, if ever.”).

At a minimum, however, a comparison of Plan C657 and Plan C001, the

1980’s Congressional districting plan, strongly suggests that compactness as

measured by a “eyeball” approach was much less important in Plan C657. This is

especially true of the major urban counties, namely Dallas and Harris. Cf.

Plaintiff Exh. 28A (map of Plan C001) wjth Plaintiff Exh. 34B (map of Plan

C657).

16a

C. The 1991 Congressional Redistricting Process

l i General Background

The Texas Constitution requires the Texas Legislature to redraw

Congressional Districts after each Decennial Census. See Tex. Const,

art. Ill, § 26. The Texas Legislature is a bicameral body consisting of

the Senate and the House of Representatives. See Stip. 4. In 1991,

the Texas Senate had 31 members, elected from single member

districts. See Stip. 5. Of the 31 members of the 1991 Senate, 22 were

Democrats and nine were Republicans, two were African-American,

five were Hispanic and 24 were Anglo. All of the African-American

and Hispanic members were Democrats. See State Exh. 1. The Texas

House of Representatives had 150 members, also elected from single

member districts. See Stip. 6. Of the 150 members of the 1991 Texas

House, 93 were Democrats and 57 were Republicans, 13 were

African-Americans, 20 were Hispanic, and 117 were Anglo. As in the

Senate, all of the African-American and Hispanic House members

were Democrats. See State Exh. 2.

The following committees and subcommittees of the Texas

Legislature were involved in the task of redistricting in 1990 and

1991: the Senate Select Committee on Legislative Redistricting,

chaired by Senator Bob Glasgow; the House Committee on

Redistricting, chaired by Representative Tom Uher; the Senate

Committee of the Whole on Redistricting, chaired by Senator Chet

Brooks, which had two subcommittees -- the Subcommittee on

Congressional Districts, chaired by then-State Senator Eddie Bernice

Johnson, and the Subcommittee on Legislative Redistricting chaired

by Senator Bob Glasgow;10 and the Senate Committee of the Whole,

chaired by Senator Chet Brooks.

The Senate Select Committee on Legislative Redistricting and

the House Redistricting Committee held joint regional outreach

hearings throughout the state. Specifically, the committee heard and

received testimony from individuals and organizations concerned

about redistricting in the following cities: Austin (February 28, 1990);

Lubbock (March 16, 1990); Amarillo (March 17, 1990); Corpus

The staff for the Senate Subcommittee on Legislative Redistricting

included Carl Reynolds, Chris Sharman, Shannon Noble, and Laura McElroy. See

Stip. 27. Sharman was the subcommittee’s technician and map drawer. See

6/29/94 TR. at 3-156-58.

17a

Christi (April 6, 1990); El Paso (May 18, 1990); Midland/Odessa

(May 19, 1990); Houston (June 1, 1990); Beaumont (June 22, 1990);

Tyler (June 23, 1990); Fort Worth (July 13, 1990); Dallas (July 14,

1990); Laredo (July 27, 1990); Edinburg/Harlingen (July 28, 1990);

San Antonio (August 25, 1990); and Austin (September 28, 1990). In

1991, the Senate Committee of the Whole on Redistricting held its

own public outreach hearings on a more limited scale in Houston

(April 5, 1991), Brownsville (April 26, 1991), and San Antonio (May

1, 1991). See United States Exh. 1086.

The transcripts and/or summaries of these numerous regional

hearings are voluminous. What role these hearings ultimately played

in Congressional redistricting is difficult to ascertain. At least one

Texas House member, Representative Kent Grusendorf, testified that

the regional outreach hearings — often ill-attended by legislators —

“essentially had no effect on the outcome of the redistricting process.”

6/27/94 TR. at 96. Grusendorf further observed: “At the time I think

I thought it was serious, but in hindsight I think for the most part it

was show.” Id. Nevertheless, the state relied strongly on citizen

participation in these hearings when it justified its plan to the United

States Department of Justice.

The Texas Legislative Council advised the Texas Legislature on

legal issues of concern in drafting Congressional redistricting

legislation. See Dep. of Archer at 7. Jeff Archer, lead lawyer for the

Council on redistricting, made presentations to committee members at

the regional public outreach hearings on various legal issues to be

considered in the redistricting process. See id- at 87-88. In addition,

the Council published a series on redistricting -- dubbed the “gray

books” — that together served as a more comprehensive statement of

state and federal law applicable to redistricting. See Plaintiff Exhs.

13A, 13B, 13C. The Legislative Council also developed and had

jurisdiction over REDAPPL (a/k/a ‘Red Apple’), which was the

primary software used in drawing maps during the Congressional

redistricting process. See Dep. of Archer at 30.

The challenged redistricting plan (HB1) generated litigation

before it was even passed. On May 24, 1991, Republican plaintiffs in

Terrazas v. Slagle. 821 F.Supp. 1162 (W.D. Tex. 1993), brought an

action under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the

Constitution and the Voting Rights Act against various officials of the

18a

State of Texas and the Texas Democratic Party. In their First

Amended Original Complaint, filed after the adoption of HB1, the

plaintiffs in Terrazas challenged the 1991 Texas Congressional

Redistricting Plan as unconstitutional and violative of the Voting

Rights Act and alleged that it

sacrifices the rights of racial and political minorities to

enhance the reelection chances of Anglo Democrat

incumbents by fragmenting and concentrating the

population centers of Hispanics and Republicans,

diminishing the likelihood that candidates of their

choice can be elected from within their communities.

United States Exh. 1005. The court in Terrazas ruled that the 1991

Texas Congressional Redistricting Plan did not dilute the voting rights

of racial, ethnic, or political minorities in violation of the Constitution

or the Voting Rights Act. See Terrazas v. Slagle. 821 F.Supp. 1162

(W.D. Tex. 1993).

The implementation of the challenged plan did increase the

minority composition of the Texas Congressional Delegation. During

the consideration of redistricting by the Texas Legislature in 1991, the

Texas Congressional Delegation had 27 members, of whom 18 were

Democrats, nine were Republicans, one was African-American, four

were Hispanic, and 22 were Anglo. See Stips. 46-47. As a result of

the 1990 Census, the Texas Congressional Delegation increased to 30

members. See Stip. 48. Of the 30 members of the Texas

Congressional Delegation elected in 1992 after the 1991 redistricting -

- 20 Democrats and ten Republicans -- two are African-American, five

are Hispanic, and 23 are Anglo. See Stips. 49-50.

2. Voting Rights Act Considerations

The Legislature embarked upon Congressional redistricting

against the legal backdrop of the Voting Rights Act. As described

supra, the Texas Legislative Council through the “gray books”

attempted to summarize Voting Rights Act concerns for the Texas

Legislature." Further, Jeff Archer, the Council’s lead lawyer on

In reference to a statement made in the “gray books” that “the Gingles

standard does not appear to require a majority district to be drawn if the district

would be extremely elongated or otherwise bizarre in shape,” Jeff Archer testified

19a

redistricting, frequently testified before the Legislature’s committees

on the Voting Rights Act requirements. For instance, Archer told the

Senate Committee of the Whole on Redistricting that “mere lack of

proportional, representation is not enough” to establish a violation of

the Voting Rights Act, but is “strong evidence.” Plaintiff Exh. 16 at

10.

The Legislature also heard from concerned citizens and

organizations about the Voting Rights Act considerations relevant to

Congressional redistricting. For example, George Korbel, director of

litigation for Texas Rural Legal Aid and former regional director of

the Mexican-American Legal Defense Fund, testified before the Senate

Committee of the Whole on Redistricting that ‘Vnless there is [sic] at

least two additional Hispanic Congressional districts and one

additional Black Congressional district, . . . the reapportionment of the

Congress is not going to pass the Department of Justice.” United

States Exh. 1086 (4/5/91).

Once the redistricting legislation had passed, the Voting Rights

Act considerations in HB1 were set forth in a September 1991

attachment to the State’s § 5 submission entitled Narrative of Voting

Rights Act Considerations in Affected Districts prepared by the Texas

Congressional Redistricting Staff. See Plaintiff Exh. 4C. As the

document sets forth in its introduction, the Narrative functions to

“give an overview of the efforts made to address Voting Rights Act

concerns.” Id. at 1.

The Narrative begins by noting the legislative agreement that the

three new Congressional seats apportioned to Texas

should be configured in such a way as to allow

members of racial, ethnic, and language minorities to

elect Congressional representatives. Accordingly, the

three new districts include a predominantly black

that “those terms are to some extent attempts to explain to a person who’s not

familiar with this [redistricting] what compactness might mean.” He noted that

the statement was made in the context of a plaintiff in a redistricting case under

section 2. If the best the voters alleging the violation could do was to show that

the legislators could have connected South Texas with Houston, and then gone

over to Dallas, in his view, the State is probably not under any obligation and is

not violating the law by drawing some other forms of districts. See Dep. of Archer

at 192-193.

20a

district drawn in the Dallas County area and

predominantly Hispanic districts in the Harris County

area and in the South Texas region. In addition to

creating the three new minority districts, the proposed

Congressional redistricting plan increases the black

voting strength of the current District 18 (Harris

County) by increasing the population to assure that the

black community may continue to elect a candidate of

its choice.

Id After making these initial observations, the Narrative analyzes the

three new minority districts as well as District 18 in greater detail.

The Texas Legislature agreed that a new “Safe” African-

American district should be drawn in Dallas County.12 13 See id. at 2.

The African-American community in Dallas County insisted on a 50%

total African-American population for the district “Which the

community felt was necessary to assure its ability to elect its own

Congressional representative without having to form coalitions with

other minority groups.” Id. Meeting the threshold 50% figure meant

that more compact alternative proposals for District 30 had to be

rejected .'3 See id.

Texas legislators were aware that the failure to draw an

African-American majority district in Harris County in 1991 might be

interpreted as retrogression under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

See 6/30/94 TR. at 4-31; United States Exh. 1047. Therefore, in

order to keep District 18 as a “safe” African-American district,

“additional black population was taken from adjacent districts thereby

increasing the total African-American population to 50.9% and

The agreement on Dallas County traversed party lines. Republican

House member Kent Grusendorf testified that fairness and the Voting Rights Act

dictated that African-American voters should have a district in Dallas in which

they could elect a candidate of choice. See Dep. of Grusendorf at 47

13 r

Creation of a “safe” African-American district in Dallas County

obviously impacted the other districts in Dallas and Tarrant Counties. The

Narrative briefly discusses why the splitting of the African-American community

in Tarrant County between Districts 12 and 24 does not amount to dilution of that

minority community. See id. at 3.

21a

decreasing the total Hispanic population to 15.3%.”14 Plaintiff Exh.

4C at 5. The remaining Hispanic population was placed in District 29

-- the new “safe” Hispanic district -- consisting of a 60.6% Hispanic

population and a 10.2% African-American population. See id. The

Narrative concludes that the changes in District 18 and the

configuration of District 29 “result in the maximization of minority

voting strength for this geographical area.” Id.

In the heavily Hispanic South Texas area, the Legislature faced

no major problems concerning minority voting strength or adjustments

of population totals. See id. District 28 — the new “Safe” Hispanic

district in South Texas -- was drawn with the constant input of the

minority leadership in Bexar County and the Rio Grande Valley. See

jd. The location of District 28 in the northern portion of South Texas

was determined in part by the historical north-south configuration of

Congressional Districts 15 and 27. This was the result of attempts to

remedy a January 29, 1982 Section 5 objection which expressed

concern that the original east-west configuration of Districts 15 and

27 resulted in packing of the Hispanic population. See United States

Exh. 1065 at 9; 6/29/94 TR. at 3-169.

a. Racial Polarization

In configuring Congressional District 30 in Dallas County, the

African-American community sought 50% total African-American

population as the minimum necessary to assure that a candidate of

choice would be elected. The 50% figure was deemed significant

because “[tjhere is little evidence of coalition voting between blacks

Harris County Senator Rodney Ellis described the value of majority-

minority districts such as District 18:

Majorityf-minority] districts are important to provide

opportunities for minorities to elect candidates of their choice.

Democracy cannot function at its best when whole groups are

excluded or separated from the political process. Majority-

minority districts offer people whose philosophies have not

always been represented a chance to get into the game. The

districts do not ensure that minorities will win seats. They

ensure that their viewpoints will be represented. Often these

viewpoints are better represented by a minority, but not always.

Lawson Exh. 7, f4.

22a

and Hispanics in Dallas County” and reaching the threshold 50%

would obviate any need to form coalitions. Plaintiff Exh. 4C at 3.

In Harris County, University of Houston political scientist Dr.

Richard Murray observed that

the political alliance that had been forged between

blacks and Hispanics in the 1960’s began to break

down. Open electoral conflicts became more common.

Relations were especially strained in 1989 when, in a

contest for an open at-large seat on Houston’s city

council, and [sic] African American, Sheila Jackson

Lee, upset the favored Hispanic, former city controller

Leonel Castillo. Hispanics returned the favor in 1991

when Gracie Guzman Saenz unseated a black

incumbent in another at-large election. And in a hard-

fought mayoral race in 1991, African Americans,

rallied behind black Texas Representative Sylvester

Turner, given [sic] him 97% of their votes in a runoff.

Hispanics supported the Anglo winner, Bob Lanier, by

a nearly three to one margin.

Lawson Exh. 26 at 15. This breakdown of past coalition prompted

Hispanic strategists to argue that Hispanics and African-Americans

should not be combined in a new Harris County Congressional

district. See id. As Houston City Councilman Ben Reyes testified at

an outreach hearing held in Houston, combining minority groups in

nearly equal numbers in a new Harris County district would be the

‘Svorst scenario” because “they will vote for members of their own

ethnic group, making it more likely that a non-minority candidate will

win.”15 Plaintiff Exh. 15Hat 18.

In general, some racial or ethnic polarization occurs in majority-

minority districts in Texas. See Plaintiff Exh. 36 at 23-27. The

analysis of Dr. Allan J. Lichtman, an expert for the State of Texas,

concluded that Anglos usually bloc-voted against Hispanic candidates

The testimony of Harris County Senator Rodney Ellis is consistent with

the view that in Harris County African-Americans and Hispanics may not form

political coalitions. See Lawson Exh. 7, ^19 (”[T]he candidate of choice of the

African-American community will often not be the candidate of choice of the

Hispanic community.”)

23a

in the majority-Hispanic districts. In each of four categories, a mean

of 21% or fewer Anglo voters voted for Hispanic candidates. See

State Exh. 14 at 21 (Table 5). For the African-American majority

districts, Dr. Lichtman similarly concluded that Anglos usually bloc

voted against African-American candidates. In each of four

categories, a mean of 34% or fewer Anglo voters voted for African-

American candidates. In all categories but the legislative (which

included only one election for each district), a mean of 25% or fewer

Anglo voters voted for African-American candidates. See id. at 22.

Dr. Ronald Weber, an expert for the plaintiffs, conceded some racial

or ethnic polarization, but concluded that it is ‘hot legally or

politically consequential.” Plaintiff Exh. 36 at 27.

b. History of Discrimination

Texas has a long, well-documented history of discrimination that

has touched upon the rights of African-Americans and Hispanics to

register, to vote, or to participate otherwise in the electoral process.

Devices such as the poll tax, an all-white primary system, and

restrictive voter registration time periods are an unfortunate part of

this State’s minority voting rights history. See United States Exh.

1065 at 3; State Exh. 17 at 6. The history of official discrimination in

the Texas election process — stretching back to Reconstruction — led

to the inclusion of the State as a covered jurisdiction under Section 5

in the 1975 amendments to the Voting Rights Act. Since Texas

became a covered jurisdiction, the Department of Justice has

frequently interposed objections against the State and its subdivisions.

See United States Exh. 1095.

3. Incumbents’ Interests

As has historically been the case, Congressional incumbents

were actively involved in the redistricting process. The Texas

Democratic Congressional Delegation formed a redistricting

committee which began work in late 1989 or early 1990. See Lawson

Exh. 3, |4 . Congressman Ron Coleman, a Democrat from El Paso

and head of the Redistricting Committee, asked Democratic

incumbents what areas they wanted to represent; to the extent their

preferences overlapped, Coleman mediated between incumbents. See

id. The committee’s “overriding objective,” however, was

incumbency protection. Id. at 1)10.

24a

The Delegation played a significant role in determining the

configuration of the Congressional districts, developing their own

alternative plans and presenting those plans to state legislators. See

Lawson Exh. 3, [̂9. As Congressman Coleman observed: ‘We drew

our own plans and presented them to the Legislators, and various

members of the Delegation met with [Legislators in Austin to discuss

the incumbents’ needs and preferences. The Delegation was definitely

a force in the process.” Id.

Not surprisingly, Republican incumbents were active in the

redistricting process as well. For instance, Congressman Joe Barton

urged the joint redistricting committees to protect as many incumbent

congressmen as possible. See Plaintiff Exh. 15H at25. In short, as a

general rule, incumbents sought to influence the Legislature to draw

districts that would maximize their chances for reelection.

Furthermore, members of the Legislature openly acknowledged the

role of incumbents on the redistricting process. See United States

Exh. 1092 (Senate Committee of the Whole, transcript dated 8/24/91,

at 17) (statement of Senator Eddie Bernice Johnson: The incumbents

‘have practically drawn their own districts. Not practically, they

have.’); Plaintiff Exh. 23 at 21 (statement of Representative Uher:

‘Well, I think that not just a congressman but a large majority of the

Congressional delegation have endorsed the basic plan that we started

with, and that’s the reason that we’re still adhering to that basic plan,

is because of a majority of support of the Congressional delegation

and not just necessarily one individual congressman’s support.’).

Incumbency protection would by definition at minimum require

that incumbents not be paired against each other. Plan C657 reflects

a successful effort to avoid this result. See Stip. 52. As shown by the

various maps making up State Exh. 9B, incumbent residences

repeatedly fall just along district lines. Congressman Lamar Smith’s

residence lies in an inlet in Bexar County in the last voter tabulation

district (“VTD’) before his Congressional District 21 ends at the

northern boundary of Congressman Henry B. Gonzales’ District 20.16

Congressman Gonzales’ residence in turn lies in the last VTD before

his district ends at the southern boundary for District 21. In Dallas

County, Congressman Frost’s residence lies in a small indentation

For our purposes, a VID is the functional equivalent of a voting precinct.

25a

jutting into a part of District 30, and Congressman Bryant’s residence

lies just barely on the other side of a dividing line between District 5

and District 30. Finally, in Harris County, small indentations permit

Congressman Jack Fields’ residence to remain in District 8 and

Congressman Andrews’ residence to remain in District 25.

At least as measured by 1992 election results, the incumbents

experienced great success in redistricting to assure incumbency

protection. Each incumbent member of Congress — except Albert

Bustamante, an Hispanic Democrat who represented District 23 — was

reelected to Congress in 1992. Bustamante was defeated in the 1992

General Election by Henry Bonilla, an Hispanic Republican. See

Stip. 51. Additional specific instances of incumbent interests will be

detailed infra in the analysis of particular Congressional Districts.

4. Use of Racial Data

As with incumbency interests, particular instances in which

racial data were used in redistricting are hereafter detailed in

discussing individual Congressional Districts and their shapes.

However, some general observations about racial/ethnic information

widely available to legislators are appropriate.

Redistricting data were available to all members of the

Legislature and their staffs as well as to any groups and individuals

sponsored by members of the Legislature. See Plaintiff Exh. 13D at 1.

The primary software used for map drawing in Congressional

redistricting — REDAPPL — was readily available on work stations in

the redistricting offices of the Texas Legislative Council. See id.

The feature of REDAPPL of most interest is the system’s ability

to provide racial and ethnic data at both the VTD and block level.

REDAPPL software allowed the operator to work at the VTD level

and call up racial/ethnic information in addition to other types of

information such as population, voting age population, incumbent

location, and street names. See 6/29/94 TR. at 173. Election contest

information was available at the VTD level, see id., but REDAPPL

did not allow the operator to work with multiple elections

simultaneously on a screen.17 Indices of partisanship such as the

NCEC Index, prepared at a national level for the use of Democrats,

The REDAPPL software did not itself contain electoral databases, but

election information was available through the State’s mainframe computer.

26a

involved multiple elections, but they could not be accessed on a

REDAPPL screen. See id. at 175.

The critical feature of REDAPPL is that it allowed the operator

to “split” a VTD and work on a block-by-block level. See id- at 176.

Racial/ethnic breakdown was available on a block level on

REDAPPL. See id. at 177. By contrast, no election contest

information was available at the block level on the REDAPPL

software.18 See id. In sum, REDAPPL allowed the user to work with

racial/ethnic data at even the block level; election information was

simply unavailable at that level through REDAPPL.

If the Legislature intended to allocate voters on the basis of

race, REDAPPL certainly provided a readily available, efficient

means of doing so. In fact, because the software constantly displayed

racial and ethnic data on the screen anytime an operator used the

system, a would-be map drawer would affirmatively have to ignore the

data. See 6/30/94 TR. at 81. But as Chris Sharman, the principal

computer technician/map drawer involved in Congressional

redistricting, testified:

The problem is when you draw on this computer, it

tells you the population data, racial data. Every time

you make a move, it tabulates right there on the

screen. You can’t ignore it.

Id-

5. Congressional District 30

Describing the boundaries of Congressional District 30 is no

easy task. Even the State of Texas has difficulty analyzing the

contours of this extraordinarily oddly-configured, sprawling district.

See Appendix (Map of District 30). Dan Weiser, an expert employed

by the United States, prepared a map isolating Congressional District

30 and breaking it down into a “core” and no less than seven

segmented portions. See State Exh. 33. Even under the State’s

analysis, the “core” of District 30 accounts for only 50% of the

district’s voting age population. See id.

Election information at the block level was available — if at all — only

through the personal knowledge of Congressional incumbents and their staff.

6/29/94 TR. at 177-78.

27a

The core” of the district includes what is generally known as

South Dallas, Fair Park, and portions of South Oak Cliff and Pleasant

Grove in southeast Dallas. See United States Exh. 1070 at 9

(declaration of Dr. Paul Waddell). The district then moves northeast

from its core and splits into a northern and a western extremity. See

id. at 10. The western extremity proceeds to incorporate much of

West Dallas before it branches off to the north and south. The

southern portion gathers the “older core” of Grand Prairie, while the

northern portion moves ‘through mostly undeveloped land between

Irving and Arlington, and into the DFW Airport.” Id at 11. The

northern extremity includes a portion of the district to the northeast of

the Central Expressway characterized as “particularly complex” by

the State’s land use expert, Dr. Paul Waddell. Id. at 12.

As even a cursory glance at the map of District 30 in isolation

reveals, the district can really only be described here in the most

general terms as its meanderings are too complicated and frequent to

detail. See State Exh. 33. Thus, the remainder of the discussion of

Congressional District 30 in this portion of the opinion will focus

exclusively on the intent of the Texas Legislature in drawing the

convoluted boundaries of District 30.

According to the Narrative of Voting Rights Act Considerations

in Affected Districts, an attachment to the State’s § 5 submission, the

Texas Legislature agreed that a “safe” African-American

Congressional District would be drawn in Dallas County.19 See

Plaintiff Exh. 4C at 1-2. The African-American community insisted

upon a 50% total African-American population in order to assure a

“safe” African-American district in Dallas County. See id. at 2. The

community succeeded, as Congressional District 30 configured under

Plan C657 had a total African-American population of 50.0% and a

total Hispanic population of 17.1%. See id.

Newspaper articles appearing statewide before and during the

redistricting process confirm the view that the Legislature had early on agreed that

Dallas County would get a new minority — namely African-American — district.

See, e ^ , United States Exh. 1012 (“Redistricting Mostly Pluses for Democrats”,

Austin American-Statesman 4/21/91); United States Exh. 1017 (“Minority

District Foreseen for County”, Dallas Morning News. 12/27/90); United States

Exh. 1038 ( ‘Minority Seat May Spell Peril for 3 Congressmen”, Dallas Times

Herald. 5/5/91).

28a

The trial testimony of District 30 Congresswoman Eddie Bernice

Johnson in Terrazas v’. Slagle — a previous challenge to C657 under

the Constitution and Voting Rights Act — is consistent with the plainly

stated conclusion in the Narrative that the Texas Legislature intended

to create a safe African-American district in Dallas County. In

response to a question about whether a dominant goal existed in

redistricting Congressional Districts in Dallas County, Johnson -- who

at the time of redistricting chaired the Senate Subcommittee on

Congressional Districts and was a representative of Dallas County in

the Texas Senate — replied:

Yes. I had made a commitment to that Black

community, that they would have a safe district, as

had been mandated and expected for a number of

years, and I did not intend to go home without that.

Plaintiff Exh. 8B at 231.

In explaining the boundaries of the district, Congresswoman

Johnson testified that the district was drawn this way as a result of

two competing tensions — namely that the district was intended to be a

“safe” African-American district and the African-American population

in Dallas County had over time dispersed from its previous “core”

location. The following exchange is particularly informative:

Q.: When you say they deteriorated, what do you mean in

that respect, Mrs. Johnson?

A: Well, the population had moved -- started to move out;

there were lot of boarded up houses. The whole core

of that area was moving out. There had been a

deterioration of about 40 to 45 to 50 percent in certain

areas of voters in a 10 year period. In addition to that,

there were a large number of persons there who were

felons, who could not vote. So, though they were over

18, it substantially deteriorated their voting strength.

We then attempted to locate where that population

shifted to. And in attempting to trail that — to trace

that population, we could see that it was moving outer

and around. It was going into the Grand Prairie area

29a

and into the Pleasant Grove area. And then there were

pockets of persons who had lived here, and then this

was moved —

Q: Who lived in the Black core district?

A: — who lived in the core district, and also in the north

end of Dallas County, into Collin County. Those were

performing voters who expressed a desire to be in the

minority district. . . .

Q: Well, to the extent then that we see fingers of the . . .

district going off in the north — north Dallas County,

and even into southern Collin County, I suppose, we

are talking about these are Black migration areas that

you were attempting to bring into the district; is that

correct?

A: That is correct.

Id. at 233-35. In sum, Congresswoman Johnson testified in Terrazas

that the shape of Congressional District 30 — including the various

‘Fmger’-like extensions that are common northeast of the Central

Expressway -- can be understood as a conscious effort to pick up

African-American voters who had dispersed from the core area.20

When asked about the influence of incumbent Congressmen

Martin Frost and John Bryant on the shape of District 30,

It was widely acknowledged that then-Senator Johnson had enormous

authority in drawing the boundaries of District 30 as she saw fit:

[A]t some point the lieutenant governor made it clear that he

wanted Senator Johnson to draw her district and that the Senate,

as far as the lieutenant governor was concerned, was going to

support what she wanted to do in Dallas. And at that point it

came down to drawing her district, or the district that she would

run in, and working with accommodating Bryant on the east side

and Frost more or less on the west side to — to accomplish what

they felt that they needed to do.

Dep. of Reynolds at 23.

30a

Congresswoman Johnson testified that her sole focus in drawing the

district was on looking out for African-American voters:

Q: All right. Now, was anything done in the course of the

creation of this map, Mrs. Johnson, that you could tell

us about, to aid Congressman Bryant or Congressman

Frost? Or did this map just happen this way?

A: I got beat up so many times because I wouldn’t do

anything but look out for Black voters.

Id. at 247. Johnson -- the principal architect of District 30 —

proceeded to testify that in drawing the district she was able to pick

and choose the “performing” African-American voters she wanted to

include, leaving the “nonperforming” African-American voters for

Bryant and Frost.21 See id. at 248.

Representative Fred Blair’s testimony at trial in Terrazas is

consistent with Congresswoman Johnson’s view expressed in that

same case that the shape of the district can be explained as an effort to

locate and select ‘performing” African-American voters in order to

guarantee the African-American community a safe African-American

seat. Blair — a Texas House member from Dallas -- observed that

District 30

was crafted in a manner that we sought to pick up

those precincts, those communities, those areas that

we thought were stable areas that would present an

opportunity to elect an African-American. . . . [I]n

looking at developing a Congressional Plan, we

wanted to find those areas that we thought were stable

areas. Homeowners were very important to us. We

wanted to make sure we included a significant number

of those within a district because just to lump in

African-Americans and say we have an African-

Congressmen Frost and Bryant had a significant part of their old districts

- 24 and 5 respectively — removed to draw the safe African-American seat. As

Chris Sharman noted: “[A] good portion of the core of District 30 was in

Congressman Bryant’s district prior, and the other portion was in Congressman

Frost’s prior to redistricting . . . .” June 29, 1994 TR. at 3-187.

31a

American district that may have a number of

apartments where there is a lot of movement going on,

we thought we had to be very sure, very careful, in

drawing lines so that we could create a district that we

thought was winnable with a 50 percent.

Plaintiff Exh. 8D at 108-09. Furthermore, his testimony directly

linked this effort to find “stable areas” with the irregular shape of the

district. See id. at 109.

The testimony submitted in this racial gerrymandering case is at

first glance starkly at odds with the explanation for the district’s

severely contorted boundaries offered in Terrazas, which was of

course not a racial gerrymandering case. The most prominent

example is the testimony offered by Congresswoman Johnson in this

case.

Unlike Terrazas, where she did not acknowledge that

Congressmen Frost and Bryant had a role in determining the district’s

boundaries, Congresswoman Johnson testified for purposes of this

case that District 30 did not include some portions of the area

encompassed by her senate district because the incumbent

congressman in District 5 - John Bryant - wanted the area: “[Five]

wanted voters that they had previously represented, just as 24, just as

6, just as 5, just as everybody that had a stake in it. Everybody

wanted as much of what they had previously represented as possible

on both sides of the political spectrum.” Dep. of Johnson at 82.

Johnson further testified that a more compact African-American

majority district could have been drawn in the Dallas area if she did

not have to address the concerns of incumbents.22 See Dep. of

Johnson at 130-32, 142.

Other testimony in this case emphasized the role of

incumbents in the shaping of District 30’s bizarre boundaries. Ted

Lyon, a former member of the Texas House and Senate involved in

Congressional redistricting in 1980 and again in 1990, described in

general terms the active role of incumbents in drawing District 30:

Congresswoman Johnson in fact drew a much more compact African-

American majority district in Dallas in her Plan C500. See Plaintiff Exh. 29.

That plan drew much opposition from incumbents and was quickly abandoned.

See Part IH. E. infra.

32a

In focusing on the incumbent congressmen in the

Dallas area, it became clear almost immediately that

there would be a fight between Congressmen Frost and

Bryant, on the one hand, and Senator Eddie Bernice

Johnson, on the other, over the African-American

voters who had previously resided in Districts 3 [sic]

and 5. Frost and Bryant were not concerned about the

race of these voters. They just wanted to hold onto

enough Democrats to assure re-election. Senator

Johnson was trying to take both minority and

Democratic voters from what had previously been

Districts 24 and 5 in order to construct a majority-

black district that would satisfy the Voting Rights Act.

Conflict arose, of course, because Democratic

populations and African-American populations are

often the same. The redistricting process became a no

holds barred political fight, and fangs were out.

Lawson Exh. 14,18.

Lyon also testified about the specific impacts of incumbency

protection on the contours of the district. For instance, he attributed

the “irregular” shape of District 30 in Oak Cliff and Grand Prairie to

fighting between Frost and Johnson eventually settled by essentially

splitting the areas between Districts 24 and 30. See id. at f9. Lyon

also attributed in part some of the irregularity in the district’s eastern

shape to incumbency protection -- namely keeping Congressman

Bryant’s East Dallas neighborhood in District 5.23 See id- at HI 1.

Ted Lyon was certainly not the sole source of additional support for the

proposition that incumbency protection played a role in the boundaries of District

30. Representative Grusendorf testified that the odd configuration of District 30

was the result of protecting Frost and Bryant. Dep. of Grusendorf at 41. And Carl

Reynolds, a staff member of the Senate Subcommittee on Legislative Redistricting,

testified that there was a conflict over the Dallas area because

Frost and Bryant split Dallas County and we were forcing

another district right down in-between the two of them and

pushing them outward, and so then naturally there were

neighborhoods that one or the other had represented and there

were people that — you know, there were people that they had

33a

Apparently, Democratic incumbents in Dallas County were quite

interested in keeping African-American voters in their newly

configured districts. Congresswoman Johnson testified that

Congressman Frost was ‘looking for voters [in the urban areas of

Dallas county] that were going to vote in the Democratic Primary, and

clearly he was more likely to be sure of it if they were black.” Dep. of

Johnson at 129-130. Quite telling is an August 28, 1991 letter written

by then-Senator Johnson to John Dunne, then the head of the Civil

Rights Division at the Department of Justice, in which the Senator

requested a review of proposed Districts 12 and 24 and their

potentially dilutive effect on the minority community in Tarrant

County. See Plaintiff Exh. 6E6. In the first paragraph of this letter,

Senator Johnson explains why African-American voters were so

attractive to incumbents fighting over district boundaries:

For primary elections, approximately 97% of the total

votes cast by Blacks in the Dallas/Fort Worth

metroplex area are cast in the Democratic primary.

Because of the consistency of this voting pattern,

Democratic incumbents generally seek to include as

many Blacks as possible into their respective districts.

Throughout the course of the Congressional

redistricting process, the lines were continuously

reconfigured to assist in protecting the Democratic

incumbents in the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex area

by spreading the Black population to increase the

Democratic party index in those areas.

Id. In other words, incumbent protection in Dallas County involved

the allocation of African-American voters among the districts.

Again in contrast to her prior Terrazas testimony,

Congresswoman Johnson described in her deposition in this case a

variety of nonracial factors that went into the drawing of District 30’s

boundaries. For instance, she testified that the district mappers ‘tnade

an effort to put communities of interest together in this district. We

represented and that they wanted to continue to represent and

they had to work out the lines to do that.

Dep. of Reynolds at 24-25.

34a

made an effort to identify voters that would support the same kinds of

major issues in the same manner, notwithstanding their color.” Dep.

of Johnson at 32. Johnson further asserted that she and her staff

considered the result of certain votes in deciding whom to include in

District 30:

We looked at a couple of referenda votes for the

Dallas area rapid transit system. We also looked at a

bond election vote for the Dallas independent school

district trying to determine where there might be more

communities of interest, where there would be support

that would go beyond the color of the candidate.

Dep. of Johnson at 144.

Other testimony ostensibly supports Congresswoman

Johnson’s suggestion that “communities of interest” were put together

in District 30, In a report dated June 24, 1994, Dr, Paul Geisel, an

expert for the state, proclaims that District 30 represents a community

of interest that shares “one economy, one transportation system, one

media/communications system and one higher educational system.”

State Exh. 18 at 7.

Dr. Paul Waddell, the United States’ land use expert, in a

report prepared June 21, 1994, attempts to explain the boundaries of

District 30 in nonracial land use terms. First, most of the “arms and

fingers” of Congressional District 30 follow both natural and

commercial land use boundaries, including industrial belts, retail

areas, the Trinity River, and freeway corridors. See United States

Exh. 1070 at 8. Second, District 30’s extremities encompass within

their boundaries little single-family land use, but “clusters of multi

family land use.” Id. Third, the extremities of the district incorporate

“substantial land use areas that are office, industrial, retail, or airport

land use areas, even when these areas do not clearly serve as a bridge

to other residential areas.” Id. Fourth, the district boundaries do not,

upon close analysis, divide single family residential neighborhoods,

but in fact encompass ‘kiulti-family areas and avoid established single

family neighborhoods.” Id.

Neither Dr. Waddell nor Dr. Geisel suggested that the

Legislature had these particular “communities of interest” in mind

when drawing the boundaries of District 30. While Fred Blair’s

35a

testimony in Terrazas suggests that the map drawers preferred to

include home-dwellers over apartment-dwellers, an assertion at odds

with Dr. Waddell’s conclusions, the record is otherwise void of

support for any land use thesis. In sum, both reports undoubtedly

accurately describe the district, but are more properly seen as post hoc

descriptions of the boundaries.

6. Congressional Districts 18 and 29

According to the Narrative of Voting Rights Act Considerations

in Affected Districts, the Legislature sought to create a “safe”

Hispanic seat in the new Harris County Congressional District 29 as

well as increase African-American voting strength in District 18 in

order to assure that the African-American community could continue

to elect a “candidate of its choice.” Plaintiff Exh. 4C at 1. Prior to

redistricting in 1991, District 18 was underpopulated by 116,549

people and was made up of 35.1% total African-American population

and 42.2% total Hispanic population.24 See id. at 5. To “remedy”

this situation, additional African-American population was taken from

adjacent districts, thereby increasing the total African-American

population to 50.9%. The remaining Hispanic population was shifted

over to the new Hispanic District thereby decreasing the total

Hispanic population in District 18 to 15.3%. See id. For its part,

District 29 consists of 60.6% total Hispanic and 10.2% total African-

American population. See id.

An appreciation for the precision with which this segregation

of Hispanics and African-Americans in Harris County was carried out

may not be had without a detailed look at the map of District 18 based

on African-American population distribution by Census block and the

map of District 29 based on Hispanic population distribution by

Census block. See Plaintiff Exh. 55 and 53. The detail allowed by

these maps highlights in District 18, for example, the “many narrow

corridors, wings, or fingers that reach out to enclose black voters,

while excluding Hispanic residents.” Richard H. Pildes & Richard G.

Niemi, Expressive Harms. “Bizarre Districts.” and Voting Rights:

Evaluating Election-District Appearances After Shaw- v. Reno, 92

Mich. L. Rev. 483, 556 (1993) (hereinafter, ‘Pildes & Niemi’).

That District 18 — a safe African-American district — ended up having an

Hispanic plurality in total population is not surprising given the explosive growth

of the Hispanic community in Harris County over the 1980’s. See part II.A. supra.

36a

District 29’s border is similarly characterized by fingers reaching out

to enclose Hispanics. In fact, these districts are so finely “crafted”

that one cannot visualize their exact boundaries without looking at a

map at least three feet square.25

The geographic dispersion of the various minority

communities within Harris County is definitely an obstacle in drawing

a majority-minority district each for African-Americans and

Hispanics. As Dr. Ronald Weber, the main expert for the plaintiffs,

testified at trial, “JT]he Hispanic community is dispersed in two

quadrants about 10:00 or 11:00 o’clock on [Plaintiff Exh. 53] . . . and

about 5:00 o’clock” while the African-American community has three