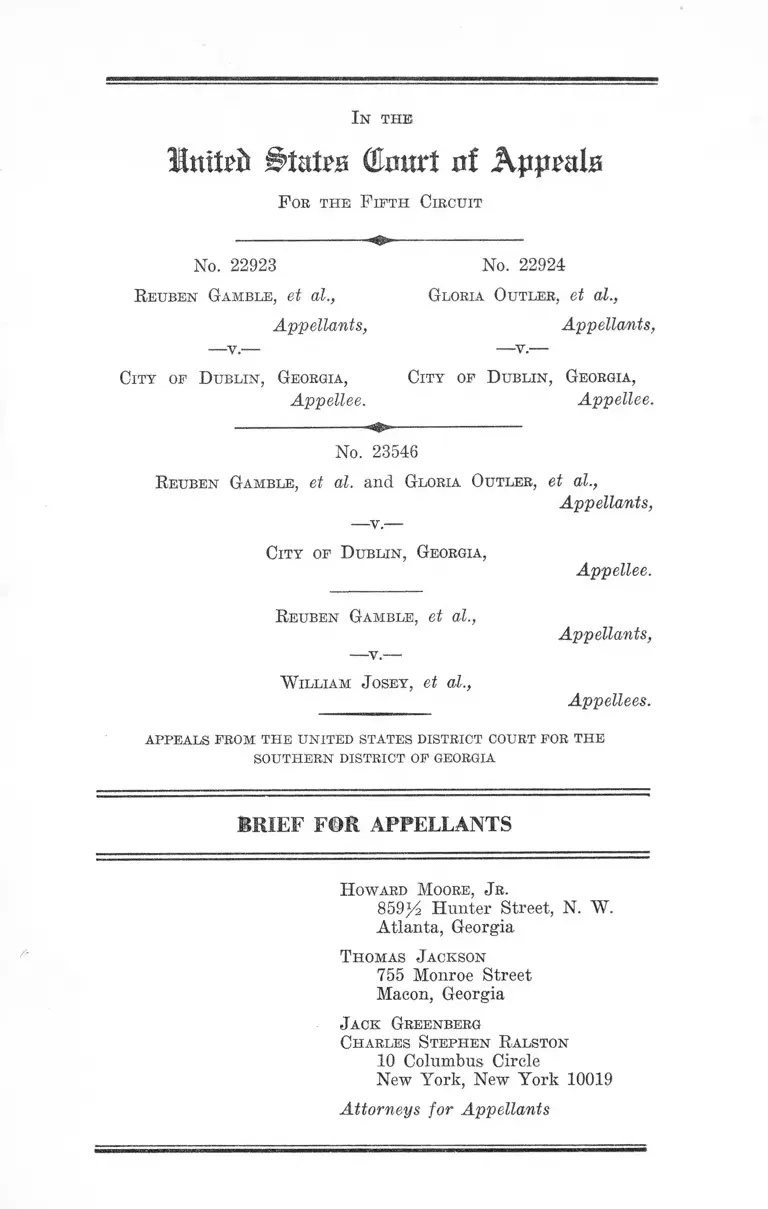

Gamble v. City of Dublin, GA Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gamble v. City of Dublin, GA Brief for Appellants, 1966. 7154c0b5-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c9e75744-3024-4fe0-a6be-196e755fa16a/gamble-v-city-of-dublin-ga-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

United States (Enurt nf Ap p e a ls

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 22923 No. 22924

Reuben Gamble, et al.,

Appellants,

Gloria Outler, et al.,

Appellants,

City of Dublin, Georgia,

Appellee.

City of Dublin, Georgia,

Appellee.

No. 23546

Reuben Gamble, et al. and Gloria Outler, et al.,

Appellants,

City of Dublin, Georgia,

Appellee.

Reuben Gamble, et al.,

Appellants,

— v.—

W illiam J osey, et al.,

Appellees.

appeals prom the united states district court for the

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OP GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

H oward Moore, J r.

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Thomas J ackson

755 Monroe Street

Macon, Georgia

J ack Greenberg

Charles Stephen Ralston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ................................................. 2

Specifications of Errors ....................... ............. ......... 13

A rgum ent :

I. In Light of the Allegations of Their Removal

Petition and the Evidence They Introduced at

the Hearing Below, Appellants-Petitioners Were

Entitled to Removal, or at Least to Pull Find

ings of Pact ........................................................ 14

II. The Ordinances of the City of Dublin With

Which the District Court’s Injunction Required

Appellants to Comply Violate the First and

Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution .... 18

C on clu sio n ....................... .............. .......... .............. .......... ......... .......... 21

A p pen d ix ....................................................................... la

T able o p Cases

Blow v. North Carolina, 379 U. S. 684 (1965) ...... 15,16,18

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808 (1966) .... 18

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569 (1941) ............. '20

20, 21Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51 (1965)

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966) .... 14,15,17,18

11

PAGE

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 (1964) ...... 15,17

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 (1937) ..................... 21

Kelly v. Page, 335 F. 2d 114 (5th Cir. 1964) .............. 19

King v. City of Clarksdale, 186 So. 2d 228 (Miss.

1966) ............................................................ 19

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938) ........................ 19

Lupper v. Arkansas, 379 U. S. 306 (1964) .......... ....... 15,17

McGee v. City of Meridian, 359 F. 2d 846 (5th. Cir.

1966) .................. 18

MeKinnie v. Tennessee, 214 Tenn. 195, 379 S. W. 2d

214 (1964) ................................................................. 16

MeKinnie v. Tennessee, 380 II. S. 449 (1965) ...... ....16,18

HAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ..................... 21

F ederal S tatute

28 U. S. C. §1443 ............................................................. 2

C ity Ordinance

Section 26-21, Code of Ordinances of the City of Dublin 20

In t h e

United States (Tmtrt nf A p p a l s

F ob th e F if t h Circuit

No. 22923

R euben Gamble, et al.,

Appellants,

C ity of D u b lin , Georgia,

Appellee.

No. 22924

Gloria C utler , et al.,

Appellants,

City of D u b l in , Georgia,

Appellee.

No. 23546

R euben Gamble, et al., an d Gloria Outler , et al.,

_ v. _

Appellants,

City of D u b lin , Georgia,

Appellee.

R buben Gamble, et al.,

Appellants,

W illiam J osey, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEALS PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

2

Statement o f the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Georgia, in three

related actions that were consolidated for trial and on ap

peal. Two of the cases,- Reuben Gamble, et al. v. City of

Dublin, Georgia, No. 22923; Gloria Outler, et al. v. City of

Dublin, Georgia, No. 22924 (and Reuben Gamble, et al. and

Gloria Outler, et al. v. City of Dublin, Georgia, in No.

23546), involved the removal of state prosecutions to the

federal district court under the provisions of 28 U. S. C.

§1443. In those cases the District Court, after a hearing,

granted the city’s motion to remand. In the third case,

Reuben Gamble, et al. v. William Josey, et al., No. 23546,

the appellants-plaintiffs below requested injunctive relief

against the enforcement of certain city ordinances and

against acts and omissions of city officials. The District

Court denied the relief sought by plaintiffs and granted

an injunction against the plaintiffs on the basis of the de

fendant’s counterclaim.

On or about August 14, 1965, appellants in the case of

Outler v. City of Dublin, No. 22924, filed their petition for

removal seeking to remove the prosecutions of 22 persons

from the Recorder’s Court of the City of Dublin to the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

Georgia (R. 4-12). Removal was supported by allegations

that the petitioners were being prosecuted because they had

committed acts protected by Title II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 (R. 7). Specifically, they claimed that they had

been arrested on August 12, 1965, while peacefully picketing

Todd’s Sinclair Service Station, an establishment covered

by Title II to protest the denial of and to attempt to secure

equal access to a place of public accommodation (R. 6-7).

3

Therefore, their arrests and threatened prosecutions were

acts intended to intimidate, threaten, coerce or punish peti

tioners for exercising rights secured by Title II of the

Civil Eights Act. The petition was supported by an affi

davit by appellant Outler (R. 10-12). Subsequently, on

August 25, 1965,. the City of Dublin filed a motion for re

mand of the cases to the Recorder’s Court (R. 13-17).

On August 16, 1965, the second petition for removal, on

behalf of the appellants in No. 22923, Gamble v. City of

Dublin, was filed in the federal district court (R. 49-55).

The allegations of the petition were substantially similar to

the first one, except that the arrests were on August 11,

and it was alleged that some of the forty-seven petitioners

were arrested at a site other than the service station in

volved, but that their arrests were also caused by their

attempts to gain equal access to the service station. There

fore, the threatened prosecutions were intended to punish

petitioners for exercising rights secured by Title II of the

1964 Act. The petition was supported by affidavits by ap

pellants Gamble and Turner (R. 55-60). On August 25,

1965, a second motion to remand was filed by the City of

Dublin, which again contested the jurisdiction of the federal

court (R. 68-72).1

1 In the removal cases a motion for further relief was filed by

petitioners on August 17, 1965, alleging that despite the filing of

the removal petitions the respondents were continuing with the

prosecutions (R. 61-65, 35-44). The District Court was asked to

enjoin the prosecutions pending a hearing on the removal petitions.

On the same day, the District Court issued an order denying the

temporary restraining order but setting a hearing for August 25

(R. 66-67). The petitioners immediately filed notices of appeal

from the denial of the temporary restraining order (R. 67, 46). On

September 28, 1965, this Court granted a motion to consolidate the

appeals in Nos. 22923, 22924, and 22925 (a third removal pro

ceeding that has since been abandoned, see R. 102) and a motion

to withdraw appellants’ motion for an injunction pending appeal

4

On August 16, 1965, a complaint was filed by Reuben

Gamble and others (appellants in No. 23546, here) against

William Josey, Chief of Police of the City of Dublin,

Georgia (R. 74-85), and on August 23, 1965, they filed a

motion for preliminary injunction. In their complaint the

plaintiffs alleged that they had been attempting to conduct

in the City of Dublin, Georgia, peaceful and nonviolent

demonstrations protesting what they considered various

denials of equal protection in the city. Among their activi

ties was included the picketing of Todd’s Sinclair Service

Station, a place of public accommodations within the mean

ing of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, on a number

of occasions. However, it was alleged, the defendant and

officers acting under his direction and control interfered

with their peaceful and lawful activities by making un

justified arrests. In addition, it was alleged that on a

number of instances when the plaintiffs had been attempt

ing to exercise their rights under Title II and the federal

constitution, the defendant had failed to provide them with

the police protection to which they were entitled and had

allowed hostile persons to engage in threats, violence and

other intimidation.

The plaintiffs asked the court to issue an order enjoining

the defendants from interfering by threats, intimidation,

or arrests with plaintiffs and members of their class peace

fully assembling, marching and demonstrating “at reason

able times and in such a way as not to create undue conges

tion or interferences with traffic in the City,” and from

against the continuation of the prosecutions (R. 47-48) in light

of the intervening action of the District Court in August 25, 1965

restraining any prosecutions until the disposition of the eases.

No. 23546, the injunction action, was consolidated with the re

maining removal cases for purposes of trial and appeal.

5

failing to provide plaintiffs with adequate police protection

against threats, violence, etc. of persons hostile to them

(E. 84).

On August 25, 1965, the defendant hied an answer and

counterclaim (E. 87-97). The answer first moved to d ism iss

the complaint on the grounds that no claim upon which

relief could be granted had been stated and the court was

without jurisdiction. Further, the defendants generally

denied the allegations of the complaint and claimed that

the picketing of the service station was not peaceable,, but

had resulted in the obstruction of the entrances and exits

of the place of business. It was also denied that there had

been any failure to provide police protection to plaintiffs

or members of their class.

In his counterclaim the defendant alleged that the plain

tiffs had conducted numerous picketing demonstrations

and boycotts in the city which had caused traffic to become

congested and which generally constituted a hazard to pub

lic safety. It was also alleged that plaintiffs had engaged

in acts of violence involving the throwing of bottles, rocks,

etc., and that they, together with certain named organiza

tions, had been fomenting violence and disorder. As a

result of these acts on the part of the plaintiffs, it was

difficult, because of limited personnel, to provide ade

quate police protection to the demonstrators and to all of

the citizens of the City of Dublin. It was also alleged that

the acts of the plaintiffs had violated certain ordinances of

the City of Dublin (E. 95-96).

The defendant prayed that the relief sought by the plain

tiffs be denied and asked the court to enjoin them from

engaging in any of the unlawful acts referred to, or in

the alternative “to set up certain guide lines and regu

lations as to how often such demonstrations can be carried

6

on, how many persons may participate, and for what length

of time that they may be allowed to picket” (B. 97).

Subsequently, on September 15, 1965,- the plaintiffs filed

a response to the counterclaim, generally denying its alle

gations (R. 98-101).

Since the three actions involved many of the same facts

and circumstances, they were consolidated and a hearing

was held at which extensive testimony was taken on both

sides. For the purposes of clarity, the evidence will be

summarized in two sections, the first relating to the picket

ing of Todd’s Sinclair Service Station, and the second re

lating to other demonstrations and events that took place in

the City of Dublin.

1 . The Arrests at T odd’s Sinclair Service Station

The arrests that led to the filing of the two removal peti

tions in this case arose out of incidents on Wednesday,

August 11, 1965, and Thursday, August 12,1965. According

to affidavits filed by the petitioners below and admitted into

evidence by the court, subject to cross-examination of the

affiants (R. 18-35), on the evening of August 11th, a group

of Negroes were picketing Todd’s Sinclair Service Station

in the City of Dublin. They were protesting what they

claimed to be denial of equal access to the facilities of the

service station for certain members of the Negro commu

nity, particularly those associated with civil rights groups

then carrying on activities in the city (R. 537). The affi

davit of Sammie Jackson stated that after the picketing

had gone on for a while policemen arrived, among them

Chief of Police William Josey, who told the pickets to

disperse and to go home. When the pickets continued to

march, the Chief told them to go home a second time, but

when they started to leave they were placed under arrest

7

(E. 22). Other arrests had occurred earlier on the same

day of persons who had been picketing (E. 27-28).

In addition, some individuals were arrested who may not

have actually been picketing but who were in the area near

the service station and who apparently were thought to be

among the pickets (E. 23-24). After the arrests at the ser

vice station itself, persons at the offices of the civil rights

organizations, which were down the block from the service

station, were arrested by police officers apparently because

at least some of them had been participating in the picket

ing (E. 30-31).

On the next day, August 12, 1965, picketing was resumed

at the service station at or about 2 :30 in the afternoon. The

first group of pickets, according to the affidavit of Gloria

Outler, consisted of only 7 or 8 persons. After a short

period, the police arrived and arrested those pickets (E.

10). Gloria Outler and others then resumed the picketing

and a few minutes later the police again arrived. One of

the policemen told them that they could not have any more

than six pickets and that the rest should leave. When all

of the pickets continued to march 3 to 5 feet apart, they

were all arrested (E. 11, 32-33).

At the hearing itself further evidence was presented in

support of the appellants-petitioners’ version of the inci

dents at the service station. Juanita Tucker testified that

she was present at Todd’s Service Station on August 11,

1965 and observed the picketing. She testified that it was

peaceful and that there were about 6 or 7 and no more than

10 pickets (E. 469-70). On cross-examination photographs,

were shown her that were said to represent the situation at

the service station at the time of the picketing. She ad

mitted that there were more than 10 pickets in the photo

graphs and perhaps as many as 25 (E. 478-79).

8

Charles Myrick testified that he took part in the picket

ing on August 11, 1965. At the time he picketed, there were

about 25 persons in the line (R. 484). He testified that the

picketing did not interfere with the traffic going along the

street (R. 486). The police came and gave orders for

the pickets to disperse, but they continued and were then

arrested. On cross-examination the witness was again

shown photographs and asked whether pickets were block

ing the driveway and entrances into the service station.

The witness said they were not (R. 490-94). Testimony of

other witnesses for the appellants generally supported the

proposition that the picketing was peaceful and orderly,

that there were up to 25 persons, and did not in and of

itself cause any blocking of the driveways. Rather, it was

indicated, any blocking was caused by the position of bar

ricades erected by the Chief of Police (R. 504-507).

Appellant Reuben Gamble testified that he observed ap

proximately 20 pickets in front of the gas station and that

there also was a group of about 50 white persons milling

around in the service station property (R. 531). After

observing the picketing he went down the street to the

NAACP-SCOPE office where he remained until he became

aware of a disturbance out on the street. He went outside

and observed the Chief of Police ordering the pickets to

disperse or they would be arrested. When they did not

disperse, the police arrested pickets and others in the area

(R. 534). Appellant testified further that the purpose of

picketing the service station was that it had refused to

serve some Negroes, especially Negroes who were active in

the civil rights movement or Negroes who were wearing

SCOPE or NAACP buttons. Instructions had been given

to the pickets to be orderly and peaceful at all times, and

9

as far as the witness observed, the instructions were carried

out (R. 537).

The testimony of the witnesses for the appellees-respon-

dents generally contradicted that of the appellants. The

Chief of Police, William Josey, testified that he went out to

the service station on August 11, and observed a number of

persons picketing. There was a total of 52 persons arrested

at that time (R. 128), some of whom were arrested near the

SCOPE headquarters, down the street from the filling sta

tion, after the Chief had issued an order for all persons in

the vicinity to leave and go to their homes (R. 129-130).

The Chief testified that he set up a barricade at the

service station because the pickets were completely block

ing the entrances to the station (R. 134). However, one

of the barricades did close off one of the driveways into the

service station (R. 137). Chief Josey testified that the

number of pickets varied from 20 on up to 50 or 60 at times,

across a 60 foot frontage in front of the service station

(R. 138-139).

The Chief returned to the service station on August 12,

1965, at which time he observed more pickets. He told them

that they should have only six pickets and that they did not

have a right to block the entrances to the service station

(R. 143-144). More of the pickets were arrested on that

day (R. 145-146). Other witnesses, including the Judge of

the Dublin Superior Court and other police officers, testi

fied generally that there were a large number of pickets at

the service station, that entrances and exits were blocked

by them and that traffic was impaired (R. 154-56, 159-61.

372-73).

One of the questions raised by the record and one that

was not completely clarified by the evidence is the identity

10

of the persons arrested at the site of the picketing itself

and those arrested a few moments later down the street

at the civil rights office. Apparently what occurred, was

that the police chief gave an order for the pickets to dis

perse. When they did not do so at first, he gave a second

order, at which time a number of the persons began to

leave. However, before they began to leave, the Chief had

already given instructions to his men to arrest the pickets.

They arrested a number of persons at the service station

and then went down the street to the office where there

were a group of people assembled. The Chief of Police

gave an order for those persons to disperse and when they

did not, all the persons at the office were arrested, includ

ing persons who had just returned from the site of the

picketing (R. 509-10, 130-32). 2

2 . Other Incidents Relating to the Issuance

of the Court’s Injunction

The remainder of the evidence taken at the trial below

related to other incidents that took place in the City of

Dublin in the Summer of 1965. In general, the appellants-

plaintiffs in the injunction action (No. 23546, here) alleged

and testified that they had been denied the right to carry

on peaceful demonstrations as guaranteed by the Four

teenth and First Amendments to the Constitution, and had

been denied adequate police protection against attack by

persons hostile to their activities.

In an affidavit introduced in support of the motion for

preliminary injunction, Maxim Karl Rice, a white civil

rights worker, testified that he was beaten by a white resi

dent of Dublin, across the street from a church that had

been a scene of a civil rights demonstration. During the

time he was being beaten, the affidavit alleged, the Chief of

11

Police and other policemen were present, but did nothing

to protect Rice. Moreover, just before the attack when

Rice and others were conducting the demonstration before

the church, a city fireman had thrown oil of mustard on

them and the Chief of Police had done nothing (R. 19-20).

Another witness testified and generally supported Rice’s

account of what occurred on July 25 (R. 501-02).

Other witnesses testified that on occasions white persons

had assaulted demonstrators in the presence of police. On

these occasions it was alleged nothing was done by the white

policemen to protect the demonstrators. For example, on

the occasion of the picketing of a business establishment

(The Winn-Dixie store), a protest against alleged racial

discrimination in hiring, white persons driving a truck

harassed the picketers, but no action was taken against

them by police officers. On the other hand, the Negro

picketers were arrested, allegedly for disobeying an officer

(R. 481-482).

The appellees-defendants in the injunction action intro

duced testimony that gave a substantially different version

of the various events. Chief Josey testified that he did not

see the initial assault against Maxim Rice, but that when

he observed it going on he took immediate action, pulled

the assailant off Rice and arrested him (R. 115-18).

In support of the counterclaim, witnesses testified that

the city had made every effort to provide demonstrators

with full protection (R. 347-50); that the police force was

limited and that the city was forced to call in from time

to time other law enforcement officials to give aid (R. 460-

61). Further, it was testified that demonstrators had failed

to follow parade routes agreed upon, and this had made it

more difficult to provide police protection (R. 368-72).

12

3 . The Disposition by the District Court

In the removal cases the District Court made no findings

of fact or conclusions of law, but merely stated:

In Criminal Case No. 1734 and Criminal Case No.

1735, the evidence is conclusive that these are not among

the type of cases which are subject to being removed

from the State Courts to the Federal Courts, therefore,

it is Ordered and Adjudged that all of the defendants

listed in Criminal Cases Nos. 1734 and 1735 be re

manded by this Court to the Recorder’s Court, City of

Dublin, Georgia . . . (R. 102-103).

As to the injunction action, the judge found that the

plaintiffs had not proved by a preponderance of evidence

that the defendant Josey had been guilty of any act or acts

complained of in the petition. To the contrary, the judge

found that all rights due to the petitioners had been granted,

and that more than adequate police protection had been

afforded them.

With regard to the cross-action on the part of the Chief

of Police, the court found that the entire activity of the

plaintiffs was “an effort to harass and embarrass” the de

fendant. Further, the court found that in many instances

the marches, demonstrations, and picketing were conducted

“in an unreasonable manner not within the contemplation

of the guarantee of freedom of speech and assembly” (R.

104). On the basis of the evidence, the court enjoined the

plaintiffs and all persons in their class, including the Dublin

Chapter of the NAACP and SCOPE, from:

Picketing, demonstrating, marching or parading in

any manner throughout the City of Dublin, except as

provided by the Ordinances of the City of Dublin, and

13

under such reasonable regulations and controls as may

be set up by the Mayor and Board of Aldermen of the

City of Dublin and the concurrence of the City Man

ager (R. 104).

Timely notices of appeal were filed from the order re

manding the two sets of prosecutions (R. 48-49, 73) and

from the order denying the plaintiff's’ motion for prelimi

nary injunction and entering a final order and judgment in

favor of defendant on his counterclaim (R. 106).

Specifications o f Errors

1. The Court below erred in remanding to the Recorder’s

Court the prosecutions removed in Nos. 22923 and 22924

in view of the allegations of the removal petitions and the

evidence presented in their support by appellants-peti-

tioners below. 2

2. The Court erred in enjoining the appellants-plaintiffs

in No. 23546 from conducting any demonstrations, marches

or picketing unless they complied with the ordinances of

the City of Dublin, Georgia, since the said ordinances vio

late the Fourteenth and First Amendments to the Constitu

tion of the United States.

14

A R G U M E N T

I.

In Light o f the Allegations o f Their Removal Petitions

and the Evidence They Introduced at the Hearing Below,

Appellants-Petitioners Were Entitled to Removal, or at

Least to Full Findings o f Fact.

In their removal petitions appellants alleged that the

purpose of the picketing of Todd’s Sinclair Service Station

was to gain equal access to a place of public accommodation

covered by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (R. 6-7, 50-51).

Therefore, their arrests and threatened prosecutions were

to punish them for attempting to exercise rights secured

by that act (R. 7, 52). At the hearing below and in their

affidavits, the appellants presented evidence which fully

supported these allegations. Thus, appellant Gamble tes

tified as to the purpose of the picketing (R. 537), and he

and other witnesses stated that the picketing was peaceful

and orderly, consisting of up to 25 persons, and did not

block or hinder the flow of traffic (R. 537, 504-05, 490, 531-

32).

Appellants contend that their allegations and the evi

dence they presented bring them within the scope of the

decision of the United States Supreme Court in the case

of Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966); and that, there

fore, if their version of the evidence is accepted as true,

they are entitled to have their prosecutions removed and

subsequently dismissed by the District Court.

The opinion of the District Court below merely stated

that, “the evidence is conclusive that these are not among

15

the type of cases which are subject to being removed” (R.

102), and remanded the prosecutions. However, since there

were no findings of fact or conclusions of law, the Court’s

decision could have been based on one of two grounds.

The first would have been that the Court disbelieved the

appellants’ evidence and therefore felt either that there had

been no discrimination on the basis of race on the part of

the service station or that the appellants were being prose

cuted for a valid reason unrelated to their efforts to deseg

regate the service station. On the other hand, the District

Court could have accepted the evidence of appellants, but

concluded as a matter of law that the prosecutions were

not removable. Appellants contend that a decision based

on the second alternative would have been in error and that

therefore this Court should,■ at the least, vacate the order

and remand the case for findings of fact.

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966), established that

a person attempting to exercise or to gain rights or priv

ileges secured by Section 201 of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, was insulated from any attempt to punish him by

Section 203(c). Therefore, if a prosecution was instituted

against him for an attempt to gain equal access to a place

of public accommodation, he was entitled to remove the

prosecution to a federal district court and have it dismissed.

The decision in Rachel relied principally on Hamm v. City

of Rock Hill and Lupper v. Arkansas, 379 IT. S. 306 (1964),

and subsequent decisions. Therefore, to determine whether

the activities of the appellants here were protected by the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, the cases prior to Rachel must be

examined.

Appellants contend that their acts fall well within the

scope of the decisions in Rloiv v. North Carolina, 379 U. S.

16

684 (1965), and McKinnie v. Tennessee, 380 U. S. 449

(1965). In Blow, two Negroes, accompanied by 35 to 40

others, approached a restaurant in North Carolina that

served whites only and that carried a sign to that effect on

its front door. The owner locked the door against the

Negroes but opened it, from time to time, to admit white

customers. Some of the Negroes waited outside on a shrub

bery box about 6 or 8 feet away, while others remained at

a distance of up to 15 feet. Although they were asked to

leave, they continued to wait quietly outside until they

were arrested. Subsequently they were indicted and con

victed for trespass. In its opinion, the Supreme Court

found that the restaurant was covered by the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 and, therefore, on the basis of Hamm, the

judgments were vacated and the indictments were ordered

dismissed.

In the McKinnie case the facts, as set out in the judgment

of the Supreme Court of Tennessee, 214 Tenn. 195, 379

S. W. 2d 214 (1964), were as follows. The defendants were

eight Negroes who attempted to gain admittance to the

B & W Cafeteria in Nashville, Tennessee. All eight entered

a small vestibule of about six feet by six feet at the cafe

teria entrance, but were barred from entering the main

part of the restaurant by a doorman. They remained in

the vestibule for a period of from 20 minutes to a half hour,

and the Tennessee Court found that they physically blocked

the entrance so that entrance to and exit from the restau

rant was not possible without great effort. There was some

pushing and shoving going on in the vestibule, and a few

white persons did manage to squeeze their way either in

or out. At one point, there were as many as 75 people on

the outside of the cafeteria attempting to get in while the

defendants were in the vestibule. The police were sum

17

moned and the defendants were subsequently convicted of

the crime of conspiring to commit an act injurious to trade

or commerce under provisions of the Tennessee Code. On

writ of certiorari, the Supreme Court reversed in a per

curiam, decision which merely cited the decision in Hamm

and Lupper.

In the present case, there is no question that the service

station is an establishment covered by the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. Service stations are specifically named in Section

201; the Sinclair company is a nation-wide chain, and it was

admitted below that Todd’s Sinclair was on a major high

way (R. 94). There was testimony that the proprietors of

the service station discriminated against at least a portion

of the Negro community because of their race (R. 537).

Finally, the conduct of the appellants, at least on the basis

of their evidence, was protected.

They testified that there were up to 25 persons picketing

to urge that they be granted the right to use the facilities

of the service station on an equal basis. Further, it was

said, the picketing was peaceful and did not block traffic.

Hamm and Rachel make it clear that if appellants had made

a direct attempt to use the facilities,' e.g., by driving auto

mobiles onto the service station’s property, parking them

in front of gas pumps, and refusing to leave unless they

were served, their conduct would be protected despite the

total blockage of the driveways to the service station and

the complete disruption of the station’s business. It would

be anomalous, to say the least, to hold that a much more

moderate course of action, consisting of a peaceful attempt

to persuade the gas station proprietors to act in con

formance with federal law, would not be protected.

Indeed, it can be argued that the appellants-petitioners’

conduct was protected even if the appellees-respondents’

18

version of the occurrences at the service station are ac

cepted. Generally, the evidence presented by the appellees

indicated that there were from forty to fifty pickets, that

ingress and egress to the station was blocked, and that

there was interference with traffic (see, answer and coun

terclaim of defendant, E. 93-94). However,- in Blow there

were 40 persons standing in front of a restaurant en

trance, and in McKinnie the entrance was almost completely

blocked and a large crowd of persons who wished to enter

gathered on the sidewalk, obstructing it. In view of the

Supreme Court’s reversal of the convictions in those cases,

appellants are entitled to have their prosecutions dismissed.

At the very least, the District Court should be instructed

to make findings of fact as to what did in fact occur at and

near the service station and to dispose of the prosecutions

depending, on the basis of those facts, whether the decision

in Rachel or that in City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384

U. S. 808 (1966) governs.13

II.

The Ordinances o f the City o f Dublin With W hich the

District Court’s Injunction Required Appellants to

Comply Violate the First and Fourteenth Amendments

to the Constitution.

In its order, the District Court enjoined the appellants

in No. 23546 from carrying on any demonstrations, picket

ing, marching or parading in any manner except as pro

vided by the ordinances of the City of Dublin and under

such “reasonable regulations and controls” as might be

established by the city government (E. 104). The ordi-

la Cf., this Court’s order in McGee v. City of Meridian, 359 F 2d

846 (5th Cir. 1966).

19

nances to which the Court referred were challenged below

by the appellants as violating the Fourteenth and First

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States (R,

108-109, 539-540).2

However, it is clear that if a parade ordinance is un

constitutional, it need not be complied with or a permit be

applied for under its provisions. See, Lovell v. Griffin,

303 U. S. 444 (1938); Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S.

569, 577 (1941). Therefore, if the ordinances of the City of

Dublin are unconstitutional, the District Court could not

require that appellants comply with them before they ex

ercised their constitutionally protected rights of free speech

and assembly. Rather, the District Court should have

granted the further relief requested by the appellees-de-

fendants in their counterclaim (R. 97) and issued an order

setting up guidelines and regulations as to how often dem

onstrations could be carried on, how many persons might

participate, and the times and manner in which the dem

onstrations could take place, following the standards set

up by this Court in the case of Kelly v. Page, 335 F. 2d 114,

118-19 (5th Cir. 1964).3

For a parade ordinance to be valid, it must set out with

sufficient specificity the standards Avhich govern the issu

ance of a permit. Moreover, those standards must be ob

2 The full text of the ordinances in question is set out in the

Appendix infra.

3 It may be noted that the Dublin ordinance is strikingly similar

to the one involved in Kelly. See, 9 R. Rel. L. Rep. 1128. “All

parades, demonstrations or public addresses on the streets are

hereby prohibited, except with the written consent of the City

Manager;” and substantially the same as the one recently struck

down by the Supreme Court of Mississippi in King v. City of

Clarksdale, 186 So. 2d 228 (Miss. 1966).

20

jective and relate to such questions as time, place and

manner of conducting the demonstrations. Cox v. New

Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569 (1941). Moreover, it must pro

vide for a prompt judicial review of a denial of a permit

in order further to prevent arbitrary action by city officials

that unduly delays the exercise of First Amendment rights.

Cf., Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51, 59-60 (1965).

The parade ordinance of the City of Dublin, however,

fails to comply with any of these standards. It only states:

In order to provide for the orderly ingress and egress

of citizens through and upon the streets of the city,

all parades, demonstrations, and addresses on the

streets are hereby prohibited, except by written con

sent of the City Manager. (Section 26-21, Code of

Ordinances of the City of Dublin) (R. 540)

This section flatly prohibits all demonstrations, parades,

and addresses, subject to the city manager’s unbridled dis

cretion to grant or deny consent to carry on a demonstra

tion depending on whether he approves or disapproves of it.

There is no definition of what constitutes a parade, dem

onstration or address and therefore no notice is given as

to when a permit is required. E.g., it is not clear whether

picketing is included at all, or whether at some point

picketing by a certain number of persons becomes a parade.

Similarly, it is not clear how many persons must be involved

before any activity is covered. Since there are no standards

as to the permissible time of demonstrations, number of

participants, size of placards, etc., there is, in effect, no

objective controls on the city manager’s determination that

“ingress and egress” may be interfered with. Thus, the

21

ordinance both fails to give fair notice of its compass (see,

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242, 261-62 (1937)) and is

“susceptible of sweeping and improper application,”

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 433 (1963). The absence

of provisions specifying the contents of an application for

a permit to carry on a demonstration compounds the prob

lems of those attempting to exercise their constitutional

rights.

Because of the absence of standards that are to govern

the action of the city manager, there is no basis by which

any reviewing agency or court can pass on his determina

tion. In addition, there is no provision for an expeditious

appeal of a denial of a parade permit, with the result that

he may bar the effective exercise of the rights of free

speech and free assembly for an indefinite length of time.

See, Freedman v. Maryland, supra.

The remainder of the Court’s order, which requires the

appellant to comply with any other “reasonable” regula

tions that may be set up, is similarly defective. It fails to

set out any governing standards to guide either the appel

lants or the city in deciding whether a demonstration or

picketing is to be allowed.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the order of the District Court

should be vacated and the action remanded with instruc

tions that in Nos. 22923 and 22924 the Court either accept

jurisdiction of the criminal prosecutions and dismiss the

same or make findings of fact to determine whether the

appellants’ conduct is protected under the Civil Bights Act

22

of 1964, and that in No. 23546 the Court issue an order

setting out in detail the terms under which appellants may

conduct demonstrations.

Respectfully submitted,

H owakd M oore, J r.

8591/2 Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

T homas J ackson

755 Monroe Street

Macon, Georgia

J ack Greenberg

Charles S t e ph e n R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on November , 1966, I served a

copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellants upon the at

torney for appellees by depositing the same in United

States mail, postage prepaid, addressed to the Honorable

Beverly B. Hayes, Attorney at Law, Dublin, Georgia.

Attorney for Appellant,

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Ordinances o f the City o f Dublin

Section 26-21. Permit required for parades, demonstra

tions, and public addresses on streets: In order to provide

for the orderly ingress and egress of citizens through and

upon the streets of the city, all parades, demonstrations,

and addresses on the streets are hereby prohibited, except

by written consent of the City Manager.

Section 26-22. Assemblies obstructing streets, public

places, prohibited. It shall be unlawful for any person to

assemble in a crowd so as in any manner obstruct the street

passage of the streets, side walks, public ways and public

grounds in the city. Each person forming a part of such

assemblage, after noticed by a duly constituted law officer

having jurisdiction, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.

Section 1-8. General Penalty, Continuing Violations:

Any person guilty of the violation of the provisions of this

Code, Ordinance of the City of Dublin, or doing any act

within the city prohibited by this Code, or an Ordinance

of the City, or failing to perform any duty required by

same, unless otherwise provided, shall be guilty of a mis

demeanor, and shall be punished at the discretion of the

court by a fine not exceeding $200.00 or by imprisonment

for a term not exceeding thirty (30) days or in lieu of fine

or imprisonment shall be sentenced to labor upon the streets

and side walks and other public works of the city for a term

not exceeding ninety days. The sentence may be in the

alternative in which ease if the fine and costs are not paid

the defendant will serve the sentence of imprisonment or

labor. Each day any violation of this Code or any Ordinance

[occurs] shall constitute a separate offense.

38