Simms v OK Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 25, 1999

70 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Simms v OK Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1999. 80a8d272-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c9ed9112-1a12-4b28-9cc6-379a65ffc5f4/simms-v-ok-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

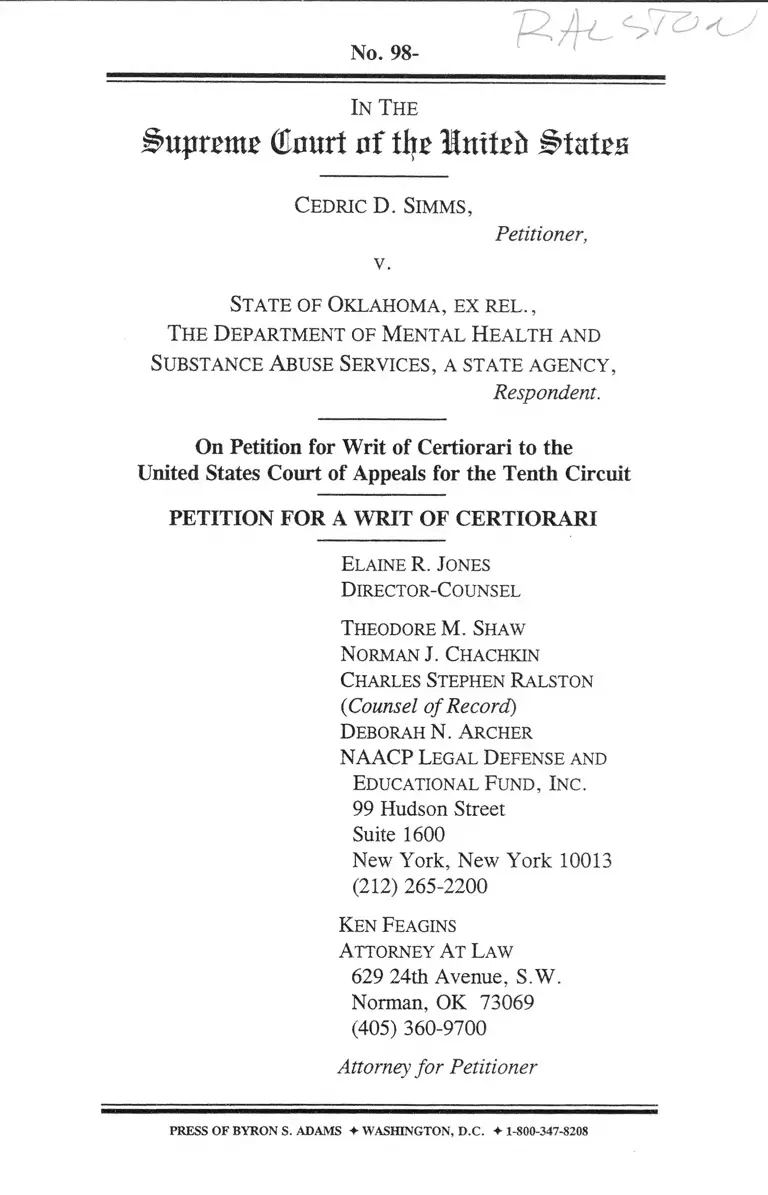

No. 98-

In The

i>u;prpmp GJflurt of tbp Im tpb S tates

Cedric D. Sim m s ,

v.

Petitioner,

Sta te of Ok la h o m a , ex r e l . ,

The D epartm ent of M ental H ea lth and

Substance Abuse Serv ices , a sta te a g e n c y ,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

E laine R. Jones

D irector-C ounsel

Theodore M . Shaw

N orm an J. C hachkin

Charles Steph en R alston

(<Counsel o f Record)

D eborah N . A r ch er

NAACP Lega l D e fen se and

Ed ucational F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 265-2200

K en F eagins

A ttorney A t L aw

629 24th Avenue, S.W.

Norman, OK 73069

(405) 360-9700

Attorney fo r Petitioner

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS ♦ WASHINGTON, D.C. ♦ 1-800-347-8208

1

Q u e s t io n P r e s e n t e d

Does an amendment to an EEOC charge of

discrimination relate back to the date of the original

charge for the purpose of complying with the statute of

limitations for Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq., where the

amendment alleges an additional "legal theory" that grows

out of the same set of operative facts that were in the

original charge?

11

P a r t ie s

A ll of the parties are listed in the caption.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Q u e s t io n P r e s e n t e d ............................................................ i

P a r t ie s .................................................... ii

T a b l e o f A u t h o r it ie s ............................................................iv

O pin io n s B e l o w ................................................................. 1

J u r is d ic t io n ............................................ 2

St a t u t e s a n d R e g u l a t io n s In v o l v e d ........................ 2

St a t e m e n t o f t h e Ca se ..................................................... 3

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W R I T ................. 8

I. T h e D e c isio n Be l o w is in

C o n fl ic t W it h D ec isio n s in

N u m e r o u s O t h e r C i r c u i t s .................. 9

II. T h is Ca se Pr esen ts Issues o f

Su bsta n tia l Im p o r t a n c e ..................... 15

III. T h e D e c isio n Be l o w is in

C o n fl ic t W it h D e c isio n s o f T his

C o u r t ............................................................. 22

A. Avoiding the Imposition of

Technical Requirements upon

Lay P e rso n s ....................... 22

B. Deference to Agency

Interpreta tions............................. 24

C o n c l u sio n 26

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Adames v. Mitsubishi Bank, Ltd., 751 F. Supp. 1565

(E.D.N.Y. 1990) ......................................... 10-12, 14

Ahmed v. Samson Management Corp., 1996 WL 183011

(S.D.N.Y. 1996)................ 11

Alpem v. UtiliCorp United, Inc., 84 F.3d 1525

(8th Cir. 1996)............ 18

Anderson v. Block, 807 F.2d 145 (8th Cir. 1986) _____ 12

B. Sanfield, Inc. v. Finaly Fine Jewelry Corp.,

168 F.3d 967 (7th Cir. 1999) .............................. 19

Bridges v. Eastman Kodak Co., 822 F. Supp. 1020

(S.D.N.Y. 1993)........... 20

Bularz v. Prudential Ins. Co. of Am., 93 F.3d 372

(7th Cir. 1996)................... 18

Caribbean Broad. System, Ltd., v. Cable & Wireless PLC,

148 F.3d 1080 (D.C. Cir. 1998) . ...................... .. . 19

Cheek v. Western and Southern Life Ins. Co., 31 F.3d 497

(7th Cir. 1994) . ................................................... .. . 20

Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.,

467 U.S. 837 (1 9 8 4 )....................................... .. 24, 25

City of Chicago v. Int’l College of Surgeons,

522 U.S. 156, _ , 139 L. Ed. 2d 525 (1 9 9 7 )___ 18

Conroy v. Boston Edison Co., 758 F. Supp. 54

(D. Mass. 1991).................................... 12-14, 20, 21

V

Pages:

Drummer v. DCI Contracting Corp., 772 F. Supp. 821

(S.D.N.Y. 1991)..................................................... . 14

Eggleston v. Chicago Journeymen Plumbers’ Local Union

No. 130, 657 F.2d 890 (7th Cir. 1981 )................. 16

Evans v. Technologies Applications & Serv. Co.,

80 F.3d 954 (4th Cir. 1996) ........................... 10, 11

Federal Deposit Ins. Corp. v. Bennett, 898 F.2d 477

(5th Cir. 1990)........................................... .. 18

Fellows v. Universal Restaurant, 701 F.2d 447

(5th Cir. 1983).............................................. .. . 23, 24

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125 (1976) . . 25

Goren v. New Vision Int’l, Inc., 156 F.3d 721

(7th Cir. 1998)................................................ .. 19

Hicks v. ABT Associates, 572 F.2d 960 (3d Cir. 1978) . 11

Hopkins v. Digital Equip. Corp., 1998 WL 702339

(S.D.N.Y. 1998)........................ ....................... 10, 11

Hornsby v. Conoco Inc., 777 F.2d 243

(5th Cir. 1985) . ................................................. 12, 13

Kahn v. Pepsi Cola Bottling Group, 526 F. Supp. 1268

(E.D.N.Y. 1981) ..................................................... 11

Lantz v. Hospital of the Univ. of Penn., 1996 WL 442795

(E.D. Pa. 1 9 9 6 )......................................... .. 10, 11

Love v. Pullman, 404 U.S. 522 (1972) 16, 22, 23

VI

Pages:

McKenzie v. Illinois D ep’t of Transp., 92 F.3d 473

(7th Cir. 1996 ).......................................................... 20

Mohasco Corp. v. Silver, 447 U.S. 807 (1980) ............... 23

Morton v. Ruiz, 415 U.S. 199 (1974) ........................ .. 25

Oates v. Discovery Zone, 116 F.3d 1161

(7th Cir. 1997 ).......................................................... 19

Paige v. California, 102 F.3d 1035 (9th Cir. 1996) . 23, 24

Pejic v. Hughes Helicopters, Inc., 840 F.2d 667

(9th Cir. 1988).................................................. 10, 11

Pena v. United States, 157 F.3d 984 (5th Cir. 1998) . . . 18

Rizzo v. WGN Continental Broad., Co., 601 F. Supp. 132

(N.D. 111. 1985) .................................................. 14

Robinson v. H. Dalton, 107 F.3d 1018 (3rd Cir. 1997) . 20

Sanchez v. Standard Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d 455

(5th Cir. 1970 )...................................... 12, 13, 15, 20

Schnellbaecher v. Baskin Clothing Co., 887 F.2d 124

(7th Cir. 1989).................................................. 16, 24

Seymore v. Shawver & Sons, Inc., I l l F.3d 794 (10th Cir.

1997), cert, denied 118 S. Ct. 342 (1997) . _____ 16

St. Francis College v. Al-Kharzaji,

481 U.S. 604 (1 9 8 7 ).......................... ........... . . . . 11

United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715 (1966) . . 19

Warren v. Halstead Indus., 1983 WL 544

(M.D.N.C. 1 9 8 3 ) ..................................................... 14

Washington v. Jenny Craig Weight Loss Centres,

3 F. Supp.2d 941 (N.D.I11. 1998)................... 20, 21

Washington v. Kroger Co., 671 F.2d 1072

(8th Cir. 1982).................................................. 12, 13

Worthington v. Wilson, 8 F.3d 1253 (7th Cir. 1993) . . . 18

Zanders v. O ’Gara-Hess, 952 F.2d 404 (6th Cir. 1992)

1992 U.S. App. Lexis 535 .................................... . 11

Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, Inc. Indep. Fed’n of Flight

Attendants, 455 U.S. 385 (1982).............. 16, 22, 23

Statutes, Rules, and Regulations:

28 U.S.C. §1254 ........................................................................ 2

29 C.F.R. §1601.12.........................................................passim

29 C.F.R. §1601.28 ................................................................... 6

29 C.F.R. §1601.34 .............................................................. 16

29 C.F.R. §1602.14 .............................................................. 17

42 U.S.C. §2000e-12(a)............................... .................. 2, 25

42 U.S.C. §§2000e-5 . ............................................................ 2

F e d . R. C iv . P. 8 ................................................................. 19

F e d . R. C iv . P. 1 5 .............................................................. 18

VI1

Pages:

F e d . R. C iv . P. 2 3 .............................................................. 23

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 .................passim

Other Authorities:

5 Ch a r l e s A l a n W r ig h t & A r t h u r R. M il l e r ,

F e d e r a l P r a c t ic e a n d P r o c e d u r e §1215

(1 9 9 0 )........................................................................ 19

V lll

Pages:

No. 98-

In T h e

Supreme Court of tfje ©mteb States;

O c to b er T e r m , 1998

Ce d r ic D. Sim m s ,

Petitioner,

■ v.

St a t e o f O k la h o m a , e x r e l .,Th e D e pa r t m e n t o f

M e n t a l H e a l t h and Su bsta n ce A b u se

Se r v ic e s , a state a g e n c y

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Petitioner Cedric D. Simms respectfully prays that

this Court issue a Writ of Certiorari to review the judgment

and opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Tenth Circuit entered on January 25, 1999.

O pin io n s Belo w

The opinion of the Tenth Circuit, which is reported

at 165 F.3d 1321 (10th Cir. 1999), is set out at pp. la-16a of

the Appendix hereto. The September 3, 1997, opinion of

the district court granting the respondent’s motion for

summary judgment, which is not reported, is set out at pp.

17a-24a of the Appendix. The decision of the court of

2

appeals denying rehearing and rehearing en banc, which is

not reported, is set out at p. 25a of the Appendix.

J u r is d ic t io n

The decision of the Tenth Circuit was entered on

January 25, 1999. A timely petition for rehearing was

denied on February 24, 1999. The jurisdiction of this Court

is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1254.

St a t u t e s a n d R e g u l a t io n s In v o lv ed

This matter involves Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq., and its

implementing regulation, 29 C.F.R. §1601.12(b), which

provides, in pertinent part:

A charge may be amended to cure technical defects

or omissions, including failure to verify the charge, or

to clarify and amplify allegations made therein. Such

amendments and amendments alleging additional

acts which constitute unlawful employment practices

related to or growing out of the subject matter of the

original charge will relate back to the date the charge

was first received. A charge that has been so

amended shall not be required to be redeferred.

The pertinent portions of Title VII, specifically 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000e-5 and 2000e-12(a), are printed at pp. 26a-28a of

the Appendix.

3

St a t e m e n t o f t h e Ca se1

Petitioner, Cedric Simms, began his employment with

the respondent at Griffin Memorial Hospital in Norman,

Oklahoma as a Fire and Safety Officer I on April 29, 1991.

(App. 2a). On September 11, 1991, the respondent posted

a job announcement for the position of Fire and Safety

Officer II. Id. Mr. Simms was qualified for the position and

applied, but the defendant gave it to a white employee less

qualified than Mr. Simms. As a result, on October 12, 1992,

Mr. Simms filed a charge with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission ("EEOC") alleging that the

respondent denied Mr. Simms the promotion because of his

race, black. Id. The EEOC issued a right-to-sue letter. On

December 21, 1993, Mr. Simms filed an action in federal

court pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq. ("Title VII"). Id.

On April 13, 1994, the parties to that case reached a

settlement. Pursuant to the settlement agreement, the

respondent promoted Mr. Simms to the position of Fire and

Safety Officer II, effective May 1, 1994. Id. Also, in the

settlement agreement the respondent agreed not to subject

Mr. Simms to the customary six (6) month probationary

period. Id. Respondent’s employees Carol Kellison,

Director of Management Support Services, and Stand

LaBoon, Superintendent, were provided with a copy of the

agreement and were aware that the agreement required the

probationary period be waived. Nevertheless, Kellison and

LaBoon withheld Mr. Simms’ supervisory duties until June

20, 1994. Id. *

‘Although this case has its origins in a complicated history of

litigation, this petition includes only those facts that are relevant to

the issue before the court.

4

On June 30, 1994, ten days after Mr. Simms began

his supervisory duties, the respondent posted a job

announcement for the position of Fire and Safety Officer

Supervisor. Id. The job announcement stated that

"PREFERENCE WILL BE GIVEN TO APPLICANTS

WITH SUPERVISORY EXPERIENCE." Id. Mr. Simms

applied, interviewed for the position, and received the

highest scores from a panel of six interviewers. Instead of

promoting Mr. Simms, Kellison initiated a second round of

interviews and selected the three member panel, which

consisted of Kellison, La Boon, and Ed Smith, an African

American. The respondent ultimately gave the position to

Bruce Valley, a white employee. At the time that Mr.

Valley was promoted he was being supervised by Mr. Simms.

Id. Nevertheless, respondent contended that Mr. Valley was

given the promotion because he had more supervisory

experience than Mr. Simms.

Unassisted by counsel, Mr. Simms filed a second

EEOC charge on October 31, 1994. (App. 2a). Mr. Simms

checked the box indicating he believed that he was

discriminated against because of his race. (The charge is

reproduced in the Appendix following App. 29a). In the

area asking for the particulars of his claim, Mr. Simms stated

that his claims arose from the denial of his promotion to the

position of Fire and Safety Officer Supervisor.2 * I. II. III.

Specifically, the charge stated:

I. Effective August 15, 1994, I was denied promotion

to the position of Fire and Safety Officer Supervisor.

II. Carol Kellison (Director Management Support

Services) informed me by written notice that a better

experienced candidate had been selected.

III. I believe I have been discriminated against because

of my race, Black, in violation of Title VII of the

5

On July 15, 1996, Mr. Simms, now having obtained

the assistance of counsel, filed an amendment to his October

31, 1994 EEOC charge. (App. 3a). Mr. Simms added

retaliation as a legal claim and explained why he believed

respondent’s decision not to promote him was motivated by

racial discrimination and retaliation for his previous lawsuit.

(See following App. 31a). He also alleged additional acts

related to the promotion denial he believed were unlawful

employment practices.3 I. II. III.

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended.

Specifically, the amendment stated:

I. Beginning in May of 1994 and continuing until the

present, I have had my supervisory duties with held

[sic] from my Fire and Safety Officer II position in

direct violation of a court order entered in a

previous EEOC charge. Effective August 15, 1994,

I was denied promotion to the position of Fire and

Safety Officer Supervisor.

II. The reasons given for withholding of supervisory

duties and other disciplinary action, I believe were

pretextural [sic]. No other reason has been given for

the withholding of supervisory duties. Carol Kellison

(Director Management Support Services) informed

me by written notice that a better experienced

candidate had been selected.

III. I believe that I have been discriminated against

because of my race, Black, and retaliated against for

filing previous charges, and for objecting to unlawful

employment practices, in violation of Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended.

This charge has been amended to include retaliation, and the

continuing violation.

6

The EEOC accepted Mr. Simms’ amendment. The

EEOC completed its investigation of the October 31, 1994

charge and, on September 25, 1996, issued a letter of

determination stating that it found "reasonable cause to

believe the charge is true." (App. 4a). Attempts at

conciliating both Mr. Simms’ retaliation and race

discrimination claims failed. On October 2, 1996, the

United States Department of Justice4 issued a right-to-sue

letter. Id. On December 31, 1996, the petitioner brought

the present action alleging that the respondent discriminated

against him on the basis of race and retaliation in violation

of Title VII. Id.

On June 16, 1997, the respondent filed a motion for

partial summary judgment, claiming that Mr. Simms’

retaliation claims asserted in the amendment to the second

charge did not relate back to the date of its filing, October

31, 1994, and were therefore time-barred. (App. 17a). The

district court granted the motion on September 3, 1997,

holding that Mr. Simms failed to exhaust his administrative

remedies. The court found that the allegations in the

amendment to the second EEOC charge related to events

that occurred more than 300 days prior to the amendment

and were not properly part of the charge, even though the

events occurred within 300 days of October 31, 1994, and

were based on the allegations in the charge that was timely

filed on that date. (App. 24a). On September 11, 1997, the

respondent filed a summary judgment motion with respect

to Mr. Simms’ remaining claims and that motion was

granted on October 23, 1997. (App. 4a).

4 Although Mr. Simms’ charge of discrimination was filed with the

EEOC, where the respondent is a government or governmental

agency, the Attorney General of the United States issues the notice

of right to sue "[w]hen there has been a finding of reasonable cause

by the [EEOC], there has been a failure of conciliation, and the

Attorney General has decided not to file a civil action." 29 C.F.R.

§1601.28(d)(l).

7

The petitioner filed a timely appeal to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. Mr. Simms

argued, inter alia, that the amendment to the charge

complies with 29 C.F.R. §1601.12(b), allowing amendments

to relate back to the date of the original charge, because it

added "additional acts which constitute unlawful employment

practices related to or growing out o f the same subject

matter as the original charge: the promotion denial.

The court below affirmed the judgment of the district

court, holding that Mr. Simms failed to exhaust his

administrative remedies with regard to his retaliation claims:

. . . [W]e hold that Mr. Simms’ retaliation charge

does not relate back under §1601.12(b) because his

1996 amendment alleges a new theory of recovery,

retaliation, that he did not raise in the second EEOC

charge.

(App. 8a).

Even though the EEOC had investigated the

retaliation charge and attempted conciliation between Mr.

Simms and the respondent, the court stated that

[prohibiting late amendments that include entirely

new theories of recovery furthers the goals of the

statutory filing period — giving the employer notice

and providing opportunity for administrative

investigation and conciliation.

(App. 8a).

On February 4, 1999, Mr. Simms filed a timely

petition for rehearing. The petition for rehearing was

denied on February 24, 1999.

8

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The petitioner in this case alleges that he was

subjected to racial discrimination and a series of retaliatory

acts. Despite a finding by the EEOC of probable cause to

believe that the petitioner was discriminated against in

violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e etseq., petitioner was prevented

from presenting his retaliation claims to a jury because the

courts below misconstrued the applicable EEOC regulation.

That regulation, 29 C.F.R. §1601.12(b), set out supra at pp.

1-2, provides that amendments to timely filed charges that

allegef] additional acts which constitute unlawful

employment practices related to or growing out of

the subject matter of the original charge will relate

back to the date the [original] charge was first

received.

29 C.F.R. §1601.12(b). The rulings below unnecessarily

penalize lay persons who fail to attach the correct legal

labels to the factual allegations in their EEOC charges. It

adopts a hyper-technical reading of the phrase "related to or

growing out o f which makes the legal "theory of recovery,"

not facts that would be known to a layperson, the

determining criterion of timeliness, notwithstanding that the

employer is put on notice by the original charge of the

specific adverse employment action — here the August, 1994

failure to promote Mr. Simms to Fire and Safety Officer

Supervisor — alleged to have been unlawful.

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted

because the decision below directly and irreconcilably

conflicts with the rulings of several other Circuits, as well as

applicable decisions of this Court. Further, the decision

resolves an important federal question in way that disrupts

settled doctrine and undermines Congress’ intent that Title

VII provide accessible and effective remedies to eradicate

9

employment discrimination.

I.

T h e D e c is io n B e l o w is in C o n fl ic t W it h

D e c isio n s in N u m e r o u s O t h e r C ir c u it s

This case concerns the Tenth Circuit’s interpretation

of 29 C.F.R. §1601.12(b), the EEOC regulation controlling

the relation back of amendments to an EEOC charge.

Substantially differing standards for applying §1601.12(b) are

in use in the federal courts. Whether a claimant will receive

a trial on the merits, or have his claims dismissed for failure

to exhaust his administrative remedies, frequently turns

solely on the district court and Circuit in which his

complaint is filed. This case presents an opportunity to

provide lower courts with a single, clear standard for

resolving this critical issue.

EEOC regulations explicitly allow the amendment of

charges of discrimination. Under the regulations, an

amendment filed outside of the applicable limitations period

will be considered timely if it is intended to "cure . . .

omissions . . . or to clarify and amplify allegations made

therein" or "allegjes] additional acts which constitute

unlawful employment practices related to or growing out of

the subject matter of the original charge." 29 C.F.R.

§1601.12(b). This language makes clear that an amendment

can allege new legal claims so long as those claims arose out

of the same set of operative facts as were alleged in the

original charge.

The court below took an exceedingly narrow view of

the regulation. The Tenth Circuit’s decision would allow

amendments to relate back only if those amendments clarify

legal theories already articulated in the original charge.

(App. 8a). The result is a blanket rule prohibiting

amendments alleging new legal claims even when those

10

claims are "related to or grow[ ] out of the subject matter of

the original charge." (App. 6a). This position is untenable

because nothing in the statute or regulation proscribes an

amendment that includes a new legal claim.

The court below correctly observed that its opinion

conflicts with those of numerous other Courts of Appeals.

(App. 7a-8a). Although the Courts of Appeals have taken

two general approaches to the issue, as set out below, there

are several distinct standards used in the lower courts.

The Fourth and Ninth Circuits have taken an

approach similar to that of the Tenth Circuit and have

concluded that an amendment will not relate back if it

advances a new theory of recovery, regardless of what facts

were included in the original charge. See Evans v.

Technologies Applications & Serv. Co., 80 F.3d 954, 963 (4th

Cir. 1996); Pejic v. Hughes Helicopters, Inc., 840 F.2d 667,

675 (9th Cir. 1988). In addition, although the Second and

Third Circuits have not directly addressed this question, two

district courts in those Circuits have followed the standard

adopted by the Fourth, Ninth and Tenth Circuits. Hopkins

v. Digital Equip. Corp., 1998 WL 702339, *2 (S.D.N.Y.

1998);5 Lantz v. Hospital o f the Univ. o f Penn., 1996 WL

442795, *4 (E.D. Pa. 1996).

The opinion in Evans demonstrates the consensus

approach of the Circuits that adopt this narrow construction

of the EEOC regulation. In Evans, the court refused to

permit relation back of an amendment adding age

discrimination to the original charge of sex discrimination,

even though both legal claims arose out of the same facts

5As with the Circuits, there is a split among the district courts in

the Second Circuit. Compare Hopkins v. Digital Equip. Corp, 1998

WL 702339^2 (S.D.N.Y. 1998), with Adames v. Mitsubishi Bank, Ltd.,

751 F. Supp. 1565, 1572-73 (E.D.N.Y. 1990).

11

and circumstances described in the original charge. Evans,

80 F.3d at 963. The court interpreted "related to or growing

out o f to mean that a new legal claim must "flow from" the

old legal claim, not from the underlying operative facts. Id.

Applying this standard, the court concluded that "age

discrimination does not necessarily flow from sex

discrimination and vice versa." Id. The court, however,

provided no guidance in determining when one legal claim

"flows" from the other.6

On the other hand, the Third, Fifth, Sixth and Eighth

Circuits have taken a more flexible approach to the

regulation and have held that the language of the regulation

encompasses claims based on different legal theories that

derive from the same set of operative facts included in the

original charge. See Hicks v. A B T Associates, 572 F.2d 960,

965 (3d Cir. 1978) (where claim of sex discrimination arose

out of the same facts as the claim of race discrimination set

out on EEOC charge, relation back is permissible if the two

claims are "directly related"); Zanders v. O ’Gara-Hess, 952

F.2d 404 (6th Cir. 1992), 1992 U.S. App. Lexis 535

(termination following suspension that was subject of

6Under this approach, few amendments have been regarded as

relating back to the original charge unless they involve the

overlapping statutorily protected categories of race, color, and

national origin. See, e.g., Kahn v. Pepsi Cola Bottling Group, 526 F.

Supp. 1268, 1270 (E.D.N.Y. 1981)(nationa! origin and race); Adames'

v. Mitsubishi Bank, 751 F. Supp. 1572 (race, color, national origin

connected); cf. St. Francis College v. Al-Kharzaji, 481 U.S. 604, 614

(1987)(Brennan, J. concurring) (ethnicity and national origin overlap

as a legal matter under Title VII); Ahmed v. Samson Management

Corp., 1996 WL 183011, *6 (S.D.N.Y. 1996) (noting that in Title VII

context, national origin claims may be treated as ancestry or ethnicity

claims). Compare, e.g., Evans, 80 F.3d 954 (sex and age not

sufficiently related); Pejic, 840 F.2d 667 (national origin and age not

sufficiently related); Hopkins, 1998 WL 702339 (race, disability and

retaliation not sufficiently related); Lantz, 1996 WL 442795 (disability

and age not sufficiently related).

12

charge); Anderson v. Block, 807 F.2d 145,149 (8th Cir. 1986)

(same); Hornsby v. Conoco Inc., I l l F.2d 243, 247 (5th Cir.

1985) ("other" box checked, age and retaliation written in,

but references to sex in factual statement held sufficient to

constitute charge on that basis); Washington v. Kroger Co.,

671 F.2d 1072, 1075-1076 (8th Cir. 1982) (second charge

properly treated as amendment of first); Sanchez v. Standard

Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d 455, 464 (5th Cir. 1970) (national

origin amendment to original charge on which "sex" box was

checked)7. In addition, although the First and Second

Circuits have not addressed the question directly, two district

courts in those Circuits have also adopted a similar

approach. Conroy v. Boston Edison Co., 758 F. Supp. 54, 58

(D. Mass. 1991); Adames v. Mitsubishi Bank, Ltd., 751 F.

Supp. 1565, 1573 (E.D.N.Y. 1990).

Underlying the opinion in Sanchez and its progeny is

the recognition that "a large number of the charges filed

with [the] EEOC are filed by ordinary people unschooled in

the technicalities of the law." Sanchez, 431 F.2d at 463

(internal citations omitted); accord Washington, 671 F.2d at

1076; Conroy, 158 F. Supp. at 60; Adames, 751 F. Supp. at

1572. Therefore, these courts hold, procedural rules

governing Title VII must be sufficiently liberal to protect

their rights. Moreover,

the crucial element of a charge of discrimination is

the factual statement contained therein. . . The

selection of the type of discrimination alleged, i.e.,

the selection of which box to check, is in reality

nothing more than the attachment of a legal

’Although the Fifth Circuit allows the amendment as a "technical

amendment" it is evident from the opinion that the additional

allegations and inclusion of a new legal theory were substantive and

of the same nature as in the other decisions cited. Sanchez, 431 F.2d

at 458-59.

13

conclusion to the facts alleged. In the context of a

statute like Title VII it is inconceivable that a

charging party’s rights should be cut off merely

because he fails to articulate correctly the legal

conclusion emanating from his factual allegations.

Sanchez, 431 F.2d at 462.

Despite these commonalities, each of these Circuits

have taken slightly different routes to reach the conclusion

that claims related to the operative facts of the original

charge are not time-barred. In Hornsby v. Conoco, Inc., the

Fifth Circuit followed the teachings of Sanchez, and applied

the bright line rule of allowing amendments containing new

legal theories to relate back where those theories are based

on facts in the original charge. Hornsby, 111 F.2d at 247;

Sanchez, 431 F.2d at 462.

Another group of courts have utilized a "scope of the

investigation" and "like or reasonably related" analysis to

determine whether claims are time-barred.8 In Washington

v. Kroger, the court began its inquiry by focusing on the

factual statement in the original charge to determine

whether it supported the new legal theory alleged in the

amendment. 671 F.2d at 1076. Next, the court looked

8The "scope of the investigation" and the "like or reasonably

related" doctrines are inquiries distinct from the question whether

amendments relate back to the date of the original charge, although

the result is the same. These two doctrines

revolvef] around the principle that the scope of a civil action

is not determined by the specific language of the charge filed

with the agency, but rather, may encompass acts of

discrimination which the [ ] investigation could reasonably be

expected to uncover.

Conroy, 758 F. Supp. at 58.

14

beyond the words of the charge to discern whether, "[h]ad

the EEOC "investigated plaintiffs first charge, it is

reasonable to suppose that it would have uncovered the

related incidents that underlay the [amendment]." Id. This

hybrid approach has also been followed by several district

courts. See, e.g. Rizzo v. WGN Continental Broad., Co., 601

F. Supp. 132, 134 (N.D. 111. 1985) (although the court

focused on the underlying facts and not legal conclusions,

the court used "like or reasonably related" and "scope of

investigation" standards to determine relation back of

amendment); Adames, 751 F. Supp. at 1573 (same);

Drummer v. DCI Contracting Corp., 772 F. Supp. 821, 826

(S.D.N.Y. 1991) (applies "like or related to" standard);

Warren v. Halstead Indus., 1983 W L544, *4 (M.D.N.C. 1983)

(erroneously stating that scope of investigation test is

codified in 29 C.F.R. §1601.12(b)).

A district court in the First Circuit applied yet

another approach. In Conroy v. Boston Edison Co., while

stating that "[a]n amendment is said to grow out of the same

subject matter as the initial charge where the protected

categories are related . . . ." 758 F. Supp. at 58, the court

went beyond this approach to hold that: "[e]ven where the

amendment alleges a new protected category . . . it will still

relate back where the predicate facts underlying each claim

are the same." Id.

The circumstances of this case crystallize the practical

consequences of those differing standards. The petitioner’s

retaliation amendment was held to be time-barred by the

Tenth Circuit because, although it grew out of the same

facts as in the original charge, it alleged a legal claim distinct

from his initial claim of racial discrimination. However, had

the petitioner been in one of the Circuits allowing

amendments alleging additional legal claims to relate back

when the amendment flows from the same facts as in the

original charge, he would have had the opportunity to

present his retaliation claims to a jury.

15

This case presents squarely for review the sole issue

of what standard should guide federal courts in determining

when amendments to an EEOC charge relate back to the

date of the original charge. The Writ of Certiorari should

be issued to resolve this mature and irreconcilable conflict

among the Circuits.

II.

T h is Ca se P r esen ts Issu es o f

Su bsta ntia l Im po r t a n c e

The decision below decides an important question in

a way that fundamentally undermines Congress’ intent in

establishing the Title VII administrative and litigative

processes. The court interprets the EEOC regulation in a

manner that is wholly inconsistent with the Title VII

enforcement scheme. Under the Tenth Circuit rule, laymen

must act with the knowledge and precision of trained lawyers

or risk losing the right to pursue their legal claims. The

opinion below, therefore, threatens the effectiveness of Title

VII as a tool to combat employment discrimination.

In Sanchez, the court carefully and precisely spelled

out why complainants must be granted latitude in identifying

the legal claims in their EEOC charges:

While the distinction between [ ] two types of

discrimination will undoubtedly be crystal clear to a

lawyer delving into the law books to research a legal

question, it may not be so apparent to an uneducated

layman who is required to put pen to paper and, by

filling out a form, to articulate his grievance as best

he can without expert legal advice.

431 F.2d at 463 n.4 (internal citations omitted). This reality

necessitates liberal construction of procedural rules if the

16

rights of Title VII plaintiffs are to be adequately protected.

Congress and the EEOC created a "user-friendly"

administrative system for the assertion of rights under Title

VII and other antidiscrimination statutes that enables lay

complainants to present their claims initially, without the

assistance of attorneys.9 See Zipes v. Trans World Airlines,

Inc. Indep. Fed’n o f Flight Attendants, 455 U.S. 385, 397

(1982); Love v. Pullman, 404 U.S. 522, 527 (1972). This

important objective is served by simplicity and flexibility in

the procedural requirements for asserting discrimination

claims.

The objective of requiring a charging party to exhaust

his administrative remedies by filing a charge with the

EEOC is to place the charged party on notice of alleged

violations, to give the EEOC sufficient information to

investigate, and to provide the parties an opportunity to

conciliate. See Seymore v. Shawver & Sons, Inc., I l l F.3d

794, 799 (10th Cir. 1997), cert, denied, 118 S. Ct. 342 (1997);

Schnellbaecher v. Baskin Clothing Co., 887 F.2d 124,127 (7th

Cir. 1989); Eggleston v. Chicago Journeymen Plumbers’ Local

Union No. 130, 657 F.2d 890, 905 (7th Cir. 1981). The rule

adopted by the Tenth Circuit undermines the administrative

scheme adopted by Congress for this purpose.

Where, as here, the EEOC has thoroughly

investigated the charge as amended and provided the parties

with an opportunity to conciliate all claims, the purpose of

the statutory exhaustion requirement is not furthered by

denying a complainant the opportunity to pursue those

claims in federal court. In addition, the respondent cannot

be said to have been prejudiced in any manner if petitioner

9In fact, EEOC regulations explicitly state that its "rules and

regulations shall be liberally construed to effectuate the purpose and

provisions of title VII . . . ." 29 C.F.R. §1601.34.

17

is permitted to proceed on his retaliation claim.10 *

The opinion below is also inconsistent with the

established procedure for filing a charge of discrimination

with the EEOC. One avenue for filing a charge with the

EEOC is to complete a charge form. On the form, the

complainant is instructed to indicate the cause of

discrimination by checking the box or boxes that describe the

type of discrimination suffered from among several listed.11

Next, the form requests the complainant to provide a

statement describing the alleged discriminatory action. The

form contains no additional instructions alerting

complainants to the significance of the selection of which

boxes to check. In this case Mr. Simms’ failure to check the

"retaliation" box had the consequence, in the view of the

court below, of completely cutting off his right to bring his

retaliation claims before a court even though they were

10For example, once petitioner’s original 1994 charge was filed,

respondent was required to preserve all of its "personnel records

relevant to the charge" until its final disposition. 29 C.F.R. §1602.14.

The regulation continues:

The term "personnel records relevant to the charge," for

example, would include personnel or employment records

related to the aggrieved person and to all other employees

holding positions similar to that held or sought by the

aggrieved person . . . .

It is inconceivable in light of this regulation that a respondent

charged with denying a specific promotion based on race could

justifiably assert that it was led by such a charge to discard records

relevant to rebutting a claim of retaliation in denying the promotion,

so that its defense has been prejudiced. Certainly no such assertion

was ever made here.

nMr. Simms’ original and amended EEOC charges of

discrimination are reproduced in the Appendix following pp. 29a and

31a.

18

investigated and unsuccessfully conciliated by the EEOC.

Ironically, the court below is enforcing a more

rigorous administrative "pleading" requirement than is

imposed on plaintiffs represented by attorneys in federal

district court in two respects. First, under Federal Rule of

Civil Procedure 15(c)(2), an amendment to a pleading

relates back to the date of the original pleading if "the claim

or defense asserted in the amended pleading arose out of

the conduct, transaction, or occurrence set forth or attempted

to be set forth in the original pleading." F e d . R. C iv . P.

15(c)(2) (emphasis added). Courts have interpreted this rule

so that

a new substantive claim that would otherwise be

time-barred relates back to the date of the original

pleading, provided the new claim stems from the

same ‘conduct, transaction, or occurrence’ as was

alleged in the original complaint; for relation back to

apply, there is no additional requirement that the

claim be based on an identical theory of recovery.

Bularz v. Prudential Ins. Co. o f Am., 93 F.3d 372, 379 (7th

Cir. 1996); accord Pena v. United States, 157 F.3d 984, 987

(5th Cir. 1998); Alpem v. UtiliCorp United, Inc., 84 F.3d 1525,

1543 (8th Cir. 1996); Worthington v. Wilson, 8 F.3d 1253,

1256 (7th Cir. 1993); Federal Deposit Ins. Corp. v. Bennett,

898 F.2d 477, 479-80 (5th Cir. 1990).12

12Cf. City o f Chicago v. Int’l College o f Surgeons, 522 U.S. 156,__,

139 L. Ed. 2d 525, 535-36 (1997), holding that the supplemental

jurisdiction of federal courts extends to

state law claims that "derive from a common nucleus of

operative fact," such that "the relationship between [the

federal] claim and the state claim permits the conclusion that

the entire action before the court comprises but one

constitutional ‘case.’" . . . The state and federal claims "derive

19

Second, the Tenth Circuit approach contrasts starkly

with the liberal pleading requirements of F e d . R. C iv . P.

8(a). Rule 8(a) requires that pleadings in federal court

contain "a short and plain statement of the claim showing

that the pleader is entitled to relief'; it does not require the

plaintiff to plead legal theories. F e d . R. C iv . P. 8(a)(2); B.

San field, Inc. v. Finaly Fine Jewelry Corp., 168 F.3d 967, 973

(7th Cir. 1999); Goren v. New Vision In t’l, Inc., 156 F.3d

721, 730, n.8 (7th Cir. 1998). See also F e d . R. C iv . P.

8(e)(1). This interpretation of Rule 8 "indicates the

objective of the rules to avoid technicalities and to require

that the pleading discharge the function of giving the

opposing party fair notice of the nature and basis or grounds

of the claim . . . ." 5 Ch a r l es Al a n W r ig h t & A r t h u r

R. M il l e r , F e d e r a l P r a c t ic e a nd P r o c e d u r e §1215,

136-138 (1990); accord Caribbean Broad. System, Ltd., v.

Cable & Wireless PLC, 148 F.3d 1080. 1085-86 (D.C. Cir.

1998).

Similarly, under EEOC regulations, a Title VII

complainant’s EEOC charge need only "describe generally

the action or practices complained of'; complainants are not

required to articulate in their EEOC charges the precise

legal theories which they will later assert in a Title VII

lawsuit. 29 C.F.R. §1601.12(b); accord Oates v. Discovery

Zone, 116 F.3d 1161, 1176 (7th Cir. 1997)(D. Wood, J.

concurring in part and dissenting in part)("it is enough both

for EEOC charges . . . and for federal complaints to set

forth the facts that will form a basis for relieff; pjlaintiffs are

not under any legal obligation to plead legal theories");

from a common nucleus of operative fact," Gibbs, supra, at

725, namely, ICS’s unsuccessful efforts to obtain demolition

permits from the Chicago Landmarks Commission.

(bracketed material in original), quoting United Mine Workers v. Gibbs,

383 U.S. 715, 725 (1966).

20

Bridges v. Eastman Kodak Co., 822 F. Supp. 1020, 1026

(S.D.N.Y. 1993) (plaintiffs are not required to state legal

theories in their EEOC charges); cf Sanchez, 431 F.2d at

463 ("the only absolutely essential element of a timely charge

of discrimination is the allegation of fact contained therein").

The ruling below requires the lay person to go beyond

accurately describing all relevant facts, to denominate

precisely the legal implications of those facts. This is

contrary to Congressional intent and defeats the objectives

of the EEOC administrative process.

The Tenth Circuit’s approach also compromises the

"scope of the investigation" rule. This doctrine

revolves around the principle that the scope of a

[Title VII] civil action is not determined by the

specific language of the charge filed with the agency,

but rather, may encompass acts of discrimination

which the [ ] investigation could reasonably be

expected to uncover.

Conroy, 758 F. Supp. at 58; accord Robinson v. H. Dalton,

107 F.3d 1018, 1025 (3rd Cir. 1997) (discussing "scope of

investigation" rule); McKenzie v. Illinois Dep’t o f Transp., 92

F.3d 473, 481 (7th Cir. 1996)(discussing "like or reasonably

related" doctrine13); Washington v. Jenny Craig Weight Loss

Centres, 3 F. Supp.2d at 947-48 (N.D.I11. 1998)(discussing

"scope of investigation" and "like or reasonably related"

rules). Courts have liberally interpreted this requirement to

ensure that meritorious claims are not turned aside because

of procedural technicalities. See Cheek v. Western and

Southern Life Ins. Co., 31 F.3d 497, 500 (7th Cir. 1994);

13The scope of the investigation rule and the "like or reasonably

related” doctrine are essentially the same inquiry. See Washington v.

Jenny Craig Weight Loss Centres, 3 F. Supp. 2d 941, 947 (N.D. 111.

1998).

21

Jenny Craig, 3 F. Supp. 2d at 947.

Wholly inconsistent with this well-settled doctrine, the

Tenth Circuit has adopted an approach that makes the legal

claims, rather than the facts, the focus of the EEOC charge

and would disallow any claim or amendment not articulated

in the original complaint. In contrast, the "scope of the

investigation" rule provides that "where the factual statement

in a plaintiffs written charge should have alerted the agency

to an alternative basis of discrimination, and should have

been investigated, the plaintiff will be allowed to allege this

claim in his or her complaint regardless of whether it was

actually investigated." Conroy, 758 F. Supp. at 58.

Mr. Simms’ case typifies the potential for injustice in

jurisdictions that follow the Tenth Circuit approach. As a

result of the Tenth Circuit’s narrow construction, Mr. Simms

was effectively barred from vindicating his rights because of

steps he took during the administrative process while

unrepresented by counsel. Although his original claim of

race discrimination was found to be timely, he was barred

from pursuing a claim that the EEOC found cause to believe

was true simply because he did not check the appropriate

box on his EEOC charge form. Because this approach

frustrates the national policy of extirpating employment

discrimination that is embodied in Title VII, this Court

should grant review to correct this error.

22

III.

T h e D e c is io n B e l o w is in C o n fl ic t W it h

D e c is io n s o f T h is C o u r t

The standard applied by the Tenth Circuit is

inconsistent with this Court’s rulings concerning the

technical burdens that should be placed on Title VII

complainants at the start of the administrative process and

the level of deference that should be given to the EEOC’s

interpretation of the statute and of its own regulations.

A. Avoiding the Imposition o f Technical

Requirements upon Lay Persons

This Court’s opinions in Love v. Pullman, 404 U.S.

522 (1972)14 and Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, Inc. Indep.

Fed’n o f Flight Attendants, 455 U.S. 385 (1982)15 gave effect

14In Love, the Tenth Circuit affirmed a grant of summaiy

judgment on the grounds that the plaintiff had failed to exhaust his

state remedies where his charge was tendered to the EEOC, the

EEOC referred the charge to the state agency, and then the EEOC

formally filed it once the state deferral agency indicated that

proceedings before it were terminated. By this time the charge would

have been time-barred had it not earlier been presented to the

EEOC. 404 U.S.’at 525. In reversing the decision of the Tenth

Circuit, this Court held that the filing procedure followed there fully

complied with the purpose of the filing requirements and that the

respondent could make no showing of prejudice to its interests. Id.

at 526. Moreover, the Court held that the procedure endorsed by the

Tenth Circuit "would serve no purpose other than the creation of an

additional procedural technicality," inappropriate where laymen are

acting without the assistance of counsel. Id. at 526-27.

15In Zipes, this Court, based on the principle enunciated in Love,

held that the time for filing a charge with the EEOC was not

jurisdictional, but was a limitations period subject to waiver and

equitable tolling.

23

to a guiding principle for construing the provisions of Title

VII: the procedural requirements of Title VII should not be

applied with technical stringency to the claims of

uncounselled complainants. Zipes, 455 U.S. at 397; Love,

404 U.S. at 527; cf Mohasco Corp. v. Silver, 447 U.S. 807,

816, n.19 (1980) ("[W]e do not believe that a court should

read in a time limitation provision that Congress has not

seen fit to include,. . . at least when dealing with ‘a statutory

scheme in which laymen unassisted by trained lawyers

initiate the process’")(quoting Love).16

The ruling below departs from this tradition. It

neither promotes the requirements of Title VII nor respects

the realities of the lay-initiated administrative process.17

16As Mohasco demonstrates, this Court has held lay complainants

to precise requirements of which they would reasonably be made

aware by a reading of the statute. But this is a far cry from

penalizing a lay person for checking the wrong box on a form —

especially absent a showing of prejudice to the entity charged.

17Unfortunately, this is only one example of the general problem

of plaintiffs finding themselves limited by actions taken without

benefit of counsel during the administrative process. For example,

some courts have refused to permit a charging party to bring a class

action suit under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 unless the charge itself used the

word "class," even though on the EEOC’s form there is no box to

check to indicate the complainant’s desire to raise class claims and no

instructions alerting complainants that special care must be given to

preserve the right to bring a class action. Other courts, cognizant

that complainants may be unaware of what "key words" can trigger

class action notification, are more generous in construing the charge.

E.g., Paige v. California, 102 F.3d 1035, 1041 (9th Cir. 1996); Fellows

v. Universal Restaurant, 701 F.2d 447, 451 (5th Cir. 1983).

Paralleling the situation with respect to "relation back" of

amendments to charges, there is a conflict among the Circuits as to

class actions. The Ninth and Fifth Circuit have adopted approaches

liberally construing charges and allowing class claims where an EEOC

investigation of class discrimination could reasonably be expected to

24

B. Deference to Agency Interpretations

The Tenth Circuit also failed to afford the EEOC’s

interpretation of its regulations the appropriate level of

deference. It is well settled that

The power of an administrative agency to administer

a congressionally created . . . program necessarily

requires the formulation of policy and the making of

rules to fill any gap left, implicitly or explicitly, by

Congress.

Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S.

check to indicate the complainant’s desire to raise class claims and no

instructions alerting complainants that special care must be given to

preserve the right to bring a class action. Other courts, cognizant

that complainants may be unaware of what "key words” can trigger

class action notification, are more generous in construing the charge.

E. g., Paige v. California, 102 F.3d 1035, 1041 (9th Cir. 1996); Fellows

v. Universal Restaurant, 701 F.2d 447, 451 (5th Cir. 1983).

Paralleling the situation with respect to "relation back" of

amendments to charges, there is a conflict among the Circuits as to

class actions. The Ninth and Fifth Circuit have adopted approaches

liberally construing charges and allowing class claims where an EEOC

investigation of class discrimination could reasonably be expected to

grow out of the allegations in the charge. See e.g., Paige, 102 F.3d at

1041 (EEOC charge alleging discriminatory denial of promotion

could support action challenging overall promotional process);

Fellows, 701 F.2d at 451 (allowing class claims because allegation in

charge that plaintiff discriminated against "because of my sex, female"

could lead to EEOC investigation of class discrimination). The

Seventh Circuit has taken a more restrictive view of the requirement,

essentially ignoring the actual or potential scope of the EEOC

investigation. See, e.g. Schnellbaecher v. Baskin Clothing Co., 887

F. 2d 124, 128 (7th Cir. 1989)(court found charge, which led to

investigation that sought "payroll records for all sales persons and an

explanation for the differences between the salaries of male and

female sales persons," insufficient to support class action).

25

837, 843 (1984), quoting Morton v. Ruiz, 415 U.S. 199, 231

(1974)(alteration in original). Furthermore, "such legislative

regulations are given controlling weight unless they are

arbitrary, capricious, or manifestly contrary to the statute."

Id. at 844.

In accepting, investigating, and attempting to

conciliate Mr. Simms’ amended EEOC charge, the EEOC

interpreted its regulation to allow Title VII complainants to

amend their charge to include new legal theories that grow

out of the operative facts articulated in the original charge.

Under the standard established in Chevron, the Tenth

Circuit should have given deference to the EEOC’s

interpretation of the statutory and administrative scheme.

First, Congress has given the EEOC explicit "authority from

time to time to issue . . . suitable procedural regulations to

carry out the provisions of this subchapter." 42 U.S.C.

§2000e-12(a). Second, the regulation at issue goes to the

heart of the EEOC’s role in the enforcement of Title VII:

investigating and conciliating charges of discrimination in the

first instance. Finally, this approach, as discussed above, is

consistent with the language, purpose and enforcement

scheme of Title VII. Accordingly, the Tenth Circuit should

have given greater deference to the EEOC’s interpretation

of 29 C.F.R. §1601.12(b).18

18Decisions of this Court giving limited deference to EEOC

interpretations have done so recognizing that "Congress, in enacting

Title VII, did not confer upon the EEOC [general] authority to

promulgate rules or regulations." General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429

U.S. 125, 141 (1976). In those circumstances the level of deference

"will depend upon the thoroughness evident in its consideration, the

validity of its reasoning, and its consistency with earlier and later

pronouncements, and all those factors which give it power to

persuade, if lacking power to control." Id. at 141. The EEOC

interpretation of 29 C.F.R. §1601.12(b) should be given greater

deference because Congress has given the EEOC explicit authority to

issue procedural regulations. 42 U.S.C. §2000e-12(a).

26

The Writ of Certiorari should be issued to address

the conflict between the foregoing decisions of this Court

and the decisions below.

C o n c l u sio n

For the foregoing reasons, the Petition for a Writ of

Certiorari should be granted and the decision of the court

below reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

E l a in e R . J o n es

D ir e c t o r -C o u n se l

T h e o d o r e M . Sh a w

N o r m a n J. C h a c h k in

Ch a r l e s St e p h e n R a l st o n

(Counsel o f Record)

D e b o r a h N. A r c h e r

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e a nd

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 265-2200

Ke n F e a g in s

A t t o r n e y a t Law

629 24th Avenue S.W.

Norman, OK 73069

(405) 360-9700

Attorneys for Petitioner

APPENDIX

la

PUBLISH

No. 97-6366

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

TENTH CIRCUIT

CEDRIC D. SIMMS,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA,

ex. rel., The Department of

Mental Health and Substance Abuse

Services, a state agency,

Defendant-Appellee

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF

OKLAHOMA (D. Ct. No. CIV-96-2158-A)

Before Tacha, Briscoe, and Murphy, Circuit Judges.

Tacha, Circuit Judge.

Plaintiff-Appellant Cedric D. Simms appeals two

orders of the district court granting summary judgment in

favor of defendant, the Oklahoma Department of Mental

Health and Substance Abuse Services ("DMHSAS") on

claims of unlawful employment discrimination and

retaliation. On appeal, plaintiff argues that: (1) his pre-1995

retaliation claims are not time-barred and (2) the district

court erred in granting summary judgment on his failure to

promote claim because he presented sufficient evidence of

pretext, creating a genuine dispute as to an issue of material

fact. We exercise jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C.§ 1291

and affirm.

2a

The procedural histoiy of this case is somewhat

complicated. Mr. Simms, an African-American, began his

employment with defendant at Griffin Memorial Hospital

around April 29, 1991, as a Fire and Safety Officer I. On

September 11, 1991, defendant posted a job announcement

for the position of Fire and Safety Officer II. Mr. Simms

applied for the position, but defendant gave it to a white

employee whom he thought was less qualified.

Consequently, he filed a charge with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission ("EEOC") on October 12, 1992

(No. 311930053), alleging that defendant refused to promote

him because of his race. The EEOC issued a right-to-sue

letter and, on December 21,1993, Mr. Simms filed an action

in federal court pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

("Title VII"). The parties settled this action ("Simms I") on

April 13, 1994. Under the settlement agreement, defendant

promoted Mr, Simms to the position of Fire and Safety

Officer II. Although the court stated that DMHSAS should

waive its standard six-month probationary period for

plaintiffs, defendant’s employees Carol Kellison and Stand

LaBoon withheld Mr. Simms’ supervisory duties until June

20, 1994.

Ten days later, defendant posted a job announcement

for the position of Fire and Safety Officer Supervisor. The

job announcement stated that "PREFERENCE WTT T BE

GIVEN TO APPLICANTS WITH SUPERVISORY

EXPERIENCE." Appellant’s App. at 376. Mr. Simms

applied and interviewed for the position. Mr. Simms and

Bruce Valley, a white employee under Mr. Simms’

supervision but who had numerous years of supervisory

experience in the construction industry, received the highest

scores in the first round of interviews. A panel including

Carol Kellison and Stand LaBoon interviewed both men in

a second round and ultimately gave the promotion to Mr.

Valley. As a result, Mr. Simms filed a second EEOC charge

(No. 311950136) on October 31, 1994, alleging that

defendant unlawfully failed to promote him based on his

3a

race.

After filing the second EEOC charge, Mr. Simms’

relationship with the defendant deteriorated. In March

1995, defendant reprimanded him for "distribution of

unauthorized material" and, in April 1995, defendant

suspended him for "insubordination, not devoting full time,

attention and effort to the duties and responsibilities of

position during assigned hours of duty, and failure or

inability to perform the duties in which employed."

Appellant’s App. at 83. On June 5, 1995, Mr. Simms filed

a third EEOC charge (No. 311950898) alleging that these

acts were in retaliation for filing and pursuing his second

EEOC charge. On July 20, 1995, Mr. Simms received his

first adverse job performance evaluation. Defendant

demoted him to Fire and Safety Officer I on August 13,

1995, and ultimately terminated his employment on

September 22, 1995.

On November 29, 1995, Mr. Simms received an

EEOC right-to-sue letter regarding his third EEOC charge.

He brought aa Title VII action in federal court ("Simms II")

on January 12, 1996, alleging race-based employment

discrimination and retaliation, including allegations of

retaliatory acts occurring prior to 1995 and not covered by

his third EEOC charge. At the time he commenced Simms

II, he had not yet received a right-to-sue letter for his

second EEOC charge. On July 13, 1996, DMHSAS filed a

motion for partial summary judgment on the grounds that

Mr. Simms had failed to exhaust his administrative remedies

as to his race discrimination and pre-1995 retaliation claims.

Two days later, Mr. Simms filed an amendment to his

second EEOC charge. The amendment contained

allegations of pre-1995 acts of retaliation, including

withholding of supervisory duties for the Fire and Safety

Officer II position and failure to promote him to the Fire

and Safety Supervisor position. On September 3, 1996, the

district court granted defendant’s motion for partial

4a

summary judgment, leaving only the post-1995 retaliation

claims for trial.

The EEOC completed its investigation of the second

EEOC charge on September 25, 1996, and issued a letter of

determination stating that it found "reasonable cause to

believe the charge is true." Appellant’s App. at 274. A

right-to-sue letter followed on October 2, 1996. Based on

these events, plaintiff asked the district court to reconsider

its September 3 Order in Simms II. The court denied Mr.

Simms’ motion for reconsideration on October 23,1996. On

December 31, 1996, plaintiff brought the present action

("Simms III") reasserting the claims that were dismissed in

Simms II for failure to exhaust administrative remedies.

On January 6, 1997, Simms III was transferred to the

district court judge presiding over Simms II, and plaintiff

filed a motion to consolidate the two cases. The district

court denied the motion because it would delay Simms II,

which was set for trial in a week. The remaining claims in

Simms II were tried to a jury. The jury found in favor of

DMHSAS on the retaliatory discharge claim, but found

against DMHSAS on the other post-1995 retaliation claims

(the reprimand, suspension, negative performance

evaluation, and demotion). On February 26, 1997, the trial

court entered judgment in accordance with the jury’s verdict.

On June 16, 1997, DMHSAS filed a motion for

partial summary judgment in Simms III, claiming that Mr.

Simms’ pre-1995 retaliation claims were time-barred and did

not relate back to his original second EEOC charge. The

trial court granted the motion on September 3,1997, holding

that Mr. Simms failed to exhaust administrative remedies.

The district court found Mr. Simms’ amendment to his

second EEOC charge neither timely nor related to the

activities contained in the original charge. On September

11, 1997, defendant filed a summary judgment motion with

respect to plaintiffs remaining claims in Simms III. The

5a

court granted defendant’s motion on October 23, 1997. The

trial court denied plaintiffs motion for reconsideration of

the two orders, and this appeal followed.

Standard of Review

We review the district court’s grant of summary

judgment de novo, applying the same legal standard used by

the district court. See Byers v. City o f Albuquerque 150 F.3d

1271, 1274 (10th Cir. 1998). Summary judgment is

appropriate "if the pleadings, depositions, answers to

interrogatories, and admissions on file, together with the

affidavits, if any, show that there is no genuine-issue as to

any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to a

judgment as a matter of law." Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(c). When

applying this standard, we view the evidence and draw

reasonable inferences therefrom in the light most favorable

to the nonmoving party. See Byers, 150 F.3d at 174.

Although the movant must show the absence of a

genuine issue of material fact, he or she need not negate the

nonmovant’s claim. See, e.g., Jenkins v. Wood, 81 F.3d 988,

990 (10th Cir. 1996). Once the movant carries this burden,

the nonmovant cannot rest upon his or her pleadings, but

"must bring forward specific facts showing a genuine issue

for trial as to those dispositive matters for which [he or she]

carries the burden of proof." Id. "The mere existence of a

scintilla of evidence in support of the nonmovant’s position

is insufficient to create a dispute of fact that is "genuine’; an

issue of material fact is genuine only if the nonmovant

presents facts such that a reasonable jury could find in favor

of the nonmovant." Lawmaster v. Ward, 125 F.3d 1341, 1347

(10th Cir. 1997). If there is no genuine issue of material fact

in dispute, we determine whether the district court correctly

applied the substantive law. See Kaul v. Stephan, 83 F.3d

1208, 1212 (10th Cir. 1996).

6 a

I. Pre-1995 Retaliation Claims - Exhaustion Doctrine

A plaintiff must generally exhaust his or her

administrative remedies prior to pursuing a Title VII claim

in federal court. See, e.g., Khader v. Aspin, 1 F.3d 968, 970

(10th Cir. 1993). Thus, a plaintiff normally may not bring a

Title VII action based upon claims that were not part of a

timely-filed EEOC charge for which the plaintiff has

received a right-to-sue letter. See Seymore v. Shawver &

Sons, Inc., I l l F.3d 794, 799 (10th Cir. 1997), cert, denied,

118 S. Ct. 342 (1997). To be timely, a plaintiff must file the

charge with the EEOC within 180 days or with a state

agency within 300 days of the complained-of conduct. See

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(e)(l); 29 C.F.R. § 1601.13 (1998);

Gunnell v. Utah Valley St. College, 152 F.3d 1253, 1260 n.3

(10th cir. 1998). However, 29 C.F.R. § 1601.12(b) provides

that certain amendments may relate back to the filing date

of the original charge and, therefore, be considered timely

even if the amendment takes place after the deadlines set

forth in § 1601.13. To relate back, an amendment must (1)

correct technical defects or omissions; (2) clarify or amplify

allegations made in the original charge; or (3) add additional

Title VII violations "related to or growing out of the subject

matter of the original charge." Id. § 1601.12(b).

Mr. Simms argues that the 1996 amendment to his

second EEOC charge complies with § 1601.12(b) and that

his pre-1995 retaliation claims are therefore part of a timely-

filed EEOC charge. For this to be true, the amendment

must have either clarified or amplified allegations made in

Mr. Simms’ second EEOC charge or addressed matters that

related to or grew out of the race discrimination claim in

that charge.1 We agree with the district court that the 1996 *

‘Mr. Simms’ amendments are not technical amendments (e.g.,

correcting a name or address), rather they go to the substance of the

charge.

7a

amendment did not clarify or amplify allegations in the

second EEOC charge because the original charge, even

when construed liberally, contained no mention of the theory

of retaliation or facts supporting such a claim.

W hether the pre-1995 retaliation claims contained in

the 1996 amendment related to or grew out of the race

discrimination claim in the second EEOC charge is a closer

question. Some courts have held that this language

encompasses claims based on different legal theories that

derive from the same set of operative facts included in the

original charge. See Hornsby v. Conoco Inc., I l l F.2d 243,

247 (5th cir. 1985); Washington v. Kroger Co., 671 F.2d 1072,

1075-76 (8th Cir. 1982); Alexander v. Precision Machining,

Inc., 990 F. Supp. 1304, 1310 (D. Kan. 1997); Conroy v.

Boston Edison Co., 758 F. Supp. 54, 58 (D. Mass. 1991); cf.

Fairchild v. Forma Scientific, Inc., 147 F.3d 567, 575 (7th Cir.

1998) (stating that disability discrimination claim would not

relate back to age discrimination claim, but court might have

been more sympathetic had plaintiff "alleged facts that

supported both claims" in the first complaint).2 Other

courts have concluded that an amendment will not relate

back when it advances a new theory of recovery, regardless

of the facts included in the original complaint. See Evans v.

Technologies Applications & Serv. Co., 80 F.3d 954, 963 (4th

Cir. 1996) (denying relation back for age discrimination

claim to sex discrimination claim); Pejic v. Hughes

Helicopters, Inc., 840 F.2d 667, 675 (9th Cir. 1988) (same);

Hopkins v. Digital Equip. Corp., 1998 WL 702339, at *2

(S.D.N.Y. Oct. 8,1998) (stating that retaliation and disability

claims in amended charge did not relate back to date of

2Some courts have gone further and held that an "amendment is

said to grow out of the same subject matter as the initial charge

where the protected categories are related, as is the case, for

example, with race and national origin." Conroy, 758 F. Supp. at 58.

That, however, is not the case here.

8a

original charge, which only alleged race discrimination, "even

though those claims are based on incidents described in the

original charge, since neither disability nor retaliation claims

flow from race discrimination claims"). In Gunnell v. Utah

Valley State College, 152 F.3d 1253,1260 n.3 (10th Cir. 1998),

this court followed the latter position, noting that when an

original EEOC claim alleged only retaliation, plaintiffs

amendment to add a sexual harassment claim did not relate

back to the original charge pursuant to 29 C.F.R. §

1601.12(b). Applying the analysis from Gunnell, we hold

that Mr. Simms’ retaliation charge does not relate back

under § 1601.12(b) because his 1996 amendment alleges a

new theory of recovery, retaliation, that he did not raise in

the second EEOC charge. Prohibiting late amendments that

include entirely new theories of recovery furthers the goals

of the statutory filing period - giving the employer notice

and providing opportunity for administrative investigation

and conciliation. See Evans, 80 F.3d at 954; cf. Ingels v.

Thiokol Corp., 42 F.3d 616, 625 (10th Cir. 1994) (finding

exhaustion is not required for a retaliation claim filed during

the pendency of a discrimination claim and based on acts

that occurred after the filing of the discrimination claim

because the employer already has notice and there is little

chance a second administrative complaint would lead to

conciliation). Therefore, Mr. Simms’ pre-1995 retaliation

claims were not part of a timely-filed EEOC charge, and he

has not exhausted his administrative remedies with respect

to these claims.

Even though Mr. Simms did not properly exhaust

administrative remedies, our inquiry as to whether this court

may hear the retaliation claims has not come to an end.

This court has adopted a limited exception to the exhaustion

rule for Title VII claims when the unexhausted claim is for

"discrimination like or reasonably related to the allegations

of the EEOC charge." Ingels, 42 F.3d at 625 (quoting Brown

v. Hartshome Pub. Sch. Dist. No. 1, 864 F.2d 680, 682 (10th

cir. 1988)). We have construed the "reasonably related"

9a

exception to include most retaliatory acts subsequent to an

EEOC filing. See Seymore v. Shawver & Sons, Inc.. I l l F.3d

794, 799 (10th Cir. 1997), cert, denied, 118 S. Ct. 342 (1997).

"However, where a retaliatory act occurs prior to the filing of

a charge and the employee fails to allege the retaliatory act

or a retaliation claim in the subsequent charge, the

retaliatory act ordinarily will not reasonably relate to the

charge." Id. (emphasis added); see also Hopkins. 1998 WL

702339, at *3.

In Seymore, the plaintiff filed a discrimination

complaint with the state human rights commission and was

subsequently discharged from her job. She filed an EEOC

complaint nine days after her termination which alleged race

and sex discrimination. In district court, though, plaintiff

also alleged retaliation. See Seymore, 111 F.3d at 796. This

court found the plaintiff had failed to exhaust administrative

remedies on the retaliation claim because she was aware of

the facts constituting that claim at the time of her EEOC

filing. See id. at 799-800. This case is analogous to Seymore.

All of Mr. Simms’ allegations of pre-1995 retaliation

concerned facts occurring prior to the filing of the second

EEOC complaint. Thus, Mr. Simms does not qualify for the

"reasonably related" exception, and we may not excuse his

failure to exhaust his administrative remedies with respect to

his pre-1995 retaliation claims. We affirm the district court’s

grant of summary judgment in favor of defendant on these

claims.3

II. Race Discrimination Claim - Pretext Analysis

In determining whether to grant summary judgment

on a Title VII claim, we apply the burden-shifting

3While plaintiff also included the post-1995 retaliation claims in

his brief, he concedes that he is not attempting to relitigate these

claims, upon which a jury passed judgment in Simms II.

10a

framework set forth in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973). Under this approach, the plaintiff

initially bears the burden of production to establish a prima

facie case of a Title VII violation. See McDonnell Douglas,

411 U.S. at 802. "To carry the initial burden of establishing

a prima facie case of race discrimination for a failure to

promote claim, the plaintiff must typically show that he or

she (1) belongs to a minority group; (2) was qualified for the

promotion; (3) was not promoted; and (4) that the position

remained open or was filled with a non-minority." Reynolds