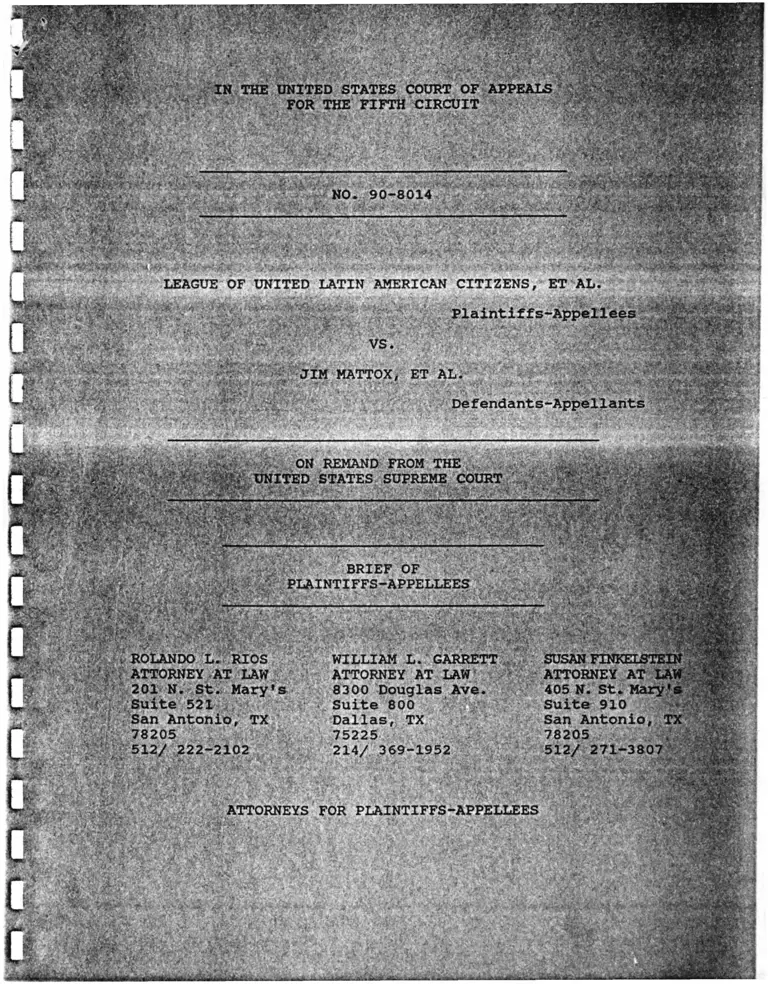

League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) v. Mattox Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) v. Mattox Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1991. 919a6736-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ca097a8d-0729-41d2-b891-3c25832f95cb/league-of-united-latin-american-citizens-lulac-v-mattox-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 02, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

NO. 90-8014

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN

JIM MATTOX

ON REMAND FROM T H E . v. .

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

ROLANDO L. RIOS

ATTORNEY AT LAW

201 N. St. Mary

Suite 521

San Antonio, TX

78205

512/ 222-2102

WILLIAM L. GARRETT

ATTORNEY AT LAW

8300 Douglas Ave.

Suite 800

Dallas, TX

75225

214/ 359-1952

ATTORNEY AT LAW

405 N. St. Mary's

Suite 910

San Antonio, TX

78205

512/ 271-3807'

~viiiiilliiwta(<iii’ iriiwh

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 90-8014

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICAN CITIZENS, ET AL.

Plaintiffs-Appellees

VS.

JIM MATTOX, ET AL.

Defendants-Appellants

ON REMAND FROM THE

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

BRIEF OF

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

ROLANDO L. RIOS

ATTORNEY AT LAW

201 N. St. Mary's

Suite 521

San Antonio, TX

78205

512/ 222-2102

WILLIAM L. GARRETT

ATTORNEY AT LAW

8300 Douglas Ave.

Suite 800

Dallas, TX

75225

214/ 369-1952

SUSAN FINKELSTEIN

ATTORNEY AT LAW

405 N. St. Mary's

Suite 910

San Antonio, TX

78205

512/ 271-3807

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PARTIES

NO. 90-8014

LULAC, et al. vs. JIM MATTOX, et al.

LOCAL RULE 28.2.1 CERTIFICATE

The undersigned, counsel of record for LULAC, et al.,

certifies that the following listed parties have an interest in the

outcome of this case. These representations are made to enable

Judges of the court to evaluate possible disqualification or

recusal.

Plaintiffs:

LULAC Local Council 4434

LULAC Local Council 4451

LULAC (Statewide)

Christina Moreno

Aquilla Watson

Joan Ervin

Matthew W. Plummer, Sr.

Jim Conley

Volma Overton

Willard Pen Conat

Gene Collins

Al Price

Theodore M. Hogrobrooks

-.Ernest M. Deckard

Judge Mary Ellen Hicks

Rev. James Thomas

Plaintiff-Intervenors:

Houston Lawyers' Association

Alice Bonner

Weldon Berry

Francis Williams

Rev. William Lawson

DeLoyd T. Parker

Bennie McGinty

Jesse Oliver

Fred Tinsley

Joan Winn White

i

Defendants:

Dan Morales, Attorney General of Texas

John Hannah, Secretary of State

Texas Judicial Districts Board

Thomas R. Phillips, Chief Justice, Texas Supreme Court

Michael J. McCormick, Presiding Judge, Court of Criminal

Appeals

Pat McDowell, Presiding Judge, 1st Admin. Judicial Region

Thomas J. Stovall, Jr., Presiding Judge, 2nd Admin.

Judicial Region

B. B. Schraub, Presiding Judge, 3rd Admin. Judicial

Region

John Cornyn, Presiding Judge, 4th Admin. Judicial Region

Darrell Hester, Presiding Judge, 5th Admin. Judicial

Region

William E. Moody, Presiding Judge, 6th Admin. Judicial

Region

Weldon Kirk, Presiding Judge, 7th Admin. Judicial Region

Jeff Walker, Presiding Judge, 8th Admin. Judicial Region

Ray D. Anderson, Presiding Judge, 9th Admin. Judicial

Region

Joe Spurlock II, President, Texas Judicial Council,

Leonard E. Davis

Defendant-Intervenors:

Judge Sharolyn Wood

Judge Harold Entz

Judge Tom Rickoff

Judge Susan D. Reed

Judge John J. Specia, Jr.

Judge Sid L. Harle

Judge Sharon MacRae

Judge Michael D. Pedan

Amicus:

Judge Larry Gist

Judge Leonard P. Giblin, Jr.

Judge Robert P. Walker

Judge Jack R. King

Judge James M. Farris

Judge Gary Sanderson

Judge Mike Bradford

Judge Patricia R. Lykos

Judge Donald K. Shipley

Judge Jay W. Burnett

Judge Bob Burdette

Judge Richard W. Millard

ii

Judge Wyatt W. Heard

Judge Michael T. McSpadden

Judge Ted Poe

Judge Joe Kegans

Judge Scott Brister

Judge Henry G. Schuble III

Judge Charles Dean Huckabee

Judge Woody R. Denson

Judge Norman R. Lee

Judge Doug Shaver

Judge Charles J. Hearn

Judge David West

Judge Tony Lindsay

Judge Louis M. Moore

Judge Dan Downey

Judge Bob Robertson

Judge John D. Montgomery

Judge Allen J. Daggett

Judge Robert S. Webb III

Judge Robert L. Lowry

Judge Robert B. Baum

Judge Eric D. Andell

Plaintiffs' Attorneys:

GARRETT & THOMPSON

William L. Garrett

Brenda Hull Thompson

Rolando L. Rios

TEXAS RURAL LEGAL AID, INC.

Susan Finkelstein

Plaintiff-Intervenors' Attorneys:

MULLENAX, WELLS, BAAB & CLOUTMAN

Edward B. Cloutman III

E. Brice Cunningham

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATION FUND,

Julius L. Chambers

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

MATTHEWS & BRANSCOMB

Gabrielle K. McDonald

INC.

iii

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TEXAS

Dan Morales

Will Pryor

Mary F. Keller

Renea Hicks

Javier P. Guajardo

Defendants' Attorneys:

Defendant-Intervenors' Attorneys:

HUGHES & LUCE

Robert H. Mow, Jr.

David C. Godbey

Bobby M. Rubarts

Esther R. Rosenbaum

PORTER & CLEMENTS

J. Eugene Clements

Evelyn V. Keyes

Darrell Smith

Michael J. Wood

Independent Counsel for George Bayoud, Secretary of State

LIDELL, SAPP. ZIVLEY, HILL & LaBOON

John L. Hill, Jr.

Andy Taylor

Independent Counsel for Ron Chapman, Thomas J. Stovall, Jr.,

B. B. Schraub, John Cornyn III, Darrell Hester, Sam M. Paxson,

Weldon Kirk, Jeff Walker:

GRAVES, DOUGHERTY, HEARON & MOODY

R. James George, Jr.

John M. Harmon

Margaret H. Taylor

Amici' Attorneys:

OPPENHEIMER, ROSENBERG, KELLEHER & WHEATLEY, INC.

Seagal V. Wheatley

Donald R. Philbin, Jr.

Michael E. Tigar

iv

Gerald H. Goldstein

Joel H. Pullen

Tom Maness

Royal B. Lea

RAMSEY & TYSON

Michael Ramsey

Daniel J. Popeo

Paul D. Kamenar

Alan B. Slobodin

Paul Strohl

Daniel M. Ogden

Walter L. Irvin

Orlando Garcia

Berta Alicia Mejia

Larry Evans

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE EDUCATIONAL FUND

Jose Garza

Judith Sanders Castro

United States' Attorney:

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES

John R. Dunne

Jessica Dunsay Silver

Mark Gross

Susan D. Carle

Attorney of Record for

LULAC, et al.

Plaintiffs-Appellees

v

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellees represents that oral

argument in the above case would be helpful to the Court because

of the factual and legal questions involved. Counsel believes that

the Court may have many questions regarding the case that can only

be answered in oral argument.

Oral argument has been set for Monday, November 4, 1991.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ITEM PAGE

Certificate of Interested Parties........................ i

Statement Regarding Oral Argument........................... vi

Table of Contents.......................................... vii

List of Authorities...........................................ix

Standards of Review and Notes on Organization of Brief . xii

Statement of Jurisdiction.................................... 1

Statement of the Issues...................................... 2

Statement of the Case........................................ 4

Course of Proceedings and Disposition

in the Trial Court ............. 4

Statement of the F a c t s .............................4

Summary of the Argument................................... 6

Argument ................................................... 9

I. Deference to District Court Findings ........... 9

II. State's Interest in At-Large Elections . . . . 11

Jurisdiction and Electoral B a s e ................ 13

Remedial Considerations ..................... 17

III. Linkage of Jurisdiction and Electoral Base . . 18

State Interest and D i l u t i o n ................... 18

Burden of P r o o f ............................... 2 0

Question of Fact or L a w ........................23

IV. Consideration of State's Interest ............. 24

State's Interests ............................. 24

C a u s a t i o n ....................................... 25

vii

V. Totality of the Circumstances..................26

VI. Contributions to Finding of Dilution ......... 29

Conclusion and Certificate of Service .................. 32

viii

Cases Pages

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U. S. 79 (1986)...................... 11

Bolden v. City of Mobile, 423 F. Supp. 384

(S. D. Ala. 1976), affirmed 571 F. 2d 238

(5th Cir. 1978), reversed on other grounds,

446 U. S. 55 (1980)............................................ 22

Bradley v. Swearingen, 525 S. W. 2d 280

(Tex. Civ. App. 1 9 7 5 ) .......................................... 16

Chisom v. Roemer, 111 S. Ct. 2354 (1991) .................... 21

Cross v. Baxter, 604 F. 2d 875 (5th Cir. 1979) ............. 23

Eu v. San Francisco Cty. Democratic Cent. Com.,

109 S. Ct. 1013 (1989) ........................................ 17

Garcia v. Dial, 596 S. W. 2d 524 (Cr. App. 1980) ........... 15

Garza v. County of Los Angeles,

918 F. 2d 763 (9th Cir. 1 9 9 0 ) ................................. 31

Gregory v. Ashcroft, 111 S. Ct. 2395 (1991).................. 20

Hendrix v. Joseph, 559 F. 2d 1265 (5th Cir. 1977) . . . . 22, 23

Houston Lawyers' Assn. v. Attorney General of Texas,

111 S. Ct. 2376 (1991) ............................. 10, 18-20, 24

Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F. 2d 364 (1984) . . . 28, 30, 31

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F. 2d 139

(5th Cir. 1977) en banc, cert, denied,

434 U. S. 968 (1977) .......................................... 30

Latin American Citizens Council #4434 v. Clements,

914 F. 2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990) en b a n c .................... 17, 27

League of United Latin Am. Citizens v. Clements,

902 F. 2d 293 (5th Cir. 1 9 9 0 ) ................................. 17

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325

(E. D. La. 1983) ............................................... 22

Monroe v. City of Woodville,

819 F. 2d 507 (5th Cir. 1 9 8 7 ) ................................. 31

Nevett v. Sides, 571 F. 2d 209 (5th Cir. 1978) ............. 23

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

IX

Nipper v. U-Haul Co., 516 S.W.2d 467

(Tex. Civ. App. 1 9 7 4 ) .......................................... 13

Reed v. State, 500 S. W. 2d 137

(Tex. Crim. App. 1973) ........................................ 16

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U. S. 613 (1982) ...................... 28

Tashjian v. Republican Party of Connecticut,

107 S. Ct. 544 (1986).......................................... 17

Thornburg v. Gingles,

106 S. Ct. 2752 (1986) .................... 10, 17, 20, 23-28, 30

U. S. v. Marengo Co. Com'n.,

731 F. 2d 1546 (11th Cir. 1 9 8 4 ) ............................... 22

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U. S. 124 (1971) .................... 21

White v. Regester, 412 U. S. 755 (1973)...................... 21

Zimmer v. KcKeithen, 485 F. 2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973),

en banc, aff'd. sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Bd.

V. Marshall, 424 U. S. 636 (1976) ....................... 20, 22, 26

Statutes

Texas Civil Practice and Remedies C o d e .......................... 14

Texas Constitution, Art. V, Sec. 18 & 1 9 .................... 16

Texas Constitution, Article 5, Section 8, ......... 14, 15, 22

Texas Government C o d e ..........................................14-16

Texas Rules of Civil P r o c e d u r e ..................................15

Other Authorities

28 Howard Law Journal No. 2, pp. 495-513, 1985,

Engstrom, Richard L., "The Reincarnation of the

Intent Standard: Federal Judges and At-Large

Election Cases." ............................................... 26

x

Senate Report No. 417, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1982), reprinted in

1982 D. S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 177 ................ 21, 22, 27,

28, 30

Texas Jurisprudence............................................ 15

xi

STANDARDS OF REVIEW

In Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U. S. 30, 106 S. Ct. 2752, 2781-

2, 92 L. Ed. 2d 25 (1986), the Supreme Court reviewed its prior

cases in the face of a contention from North Carolina and the

Untied States that an ultimate conclusion of vote dilution is a

mixed question of law and fact subject to de novo review on appeal,

reaffirmed its view that an ultimate finding of vote dilution is a

fact question subject to the clearly-erroneous standard of Rule

52(a). See also, Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F. 2d 364, 371

(5th Cir. 1984).

The trial court's finding of vote dilution in district judge

elections is reviewable under the clearly erroneous standard.

Errors of law, including use of an improper legal standard in

evaluating the at-large electoral system for district judges in

Texas, are reviewable free of the clearly erroneous rule.

Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. 2752, 2781-2, (1986).

NOTES ON ORGANIZATION OF BRIEF

Plaintiffs-Appellees' Brief on Remand to the Court argues only

the issues posed by this Court in its letter of August 6, 1991,

Other issues are argued in the Briefs of Plaintiffs-Appellees filed

previously in this cause.

Xll

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The Trial Court had jurisdiction of this case pursuant to 28

U. S. C. 1343(3) and (4), upon causes of action arising under 42

U. S. C. 1971, 1973, 1983, 1988, and the XIV and XV Amendments to

the United States Constitution. Relief was sought under 28 U. S.

C. 2201, 2202, and Rule 57, F. R. C. P.

This Court has jurisdiction to hear this appeal by virtue of

28 U. S. C. 1292 (b), in that the decision appealed has been

certified as an appealable interlocutory order of the United States

District Court for the Western District of Texas; and by virtue of

28 U. S. C. 1292 (a)(1) in that the decisions of January 2 and

January 11, 1990, issued an injunction.

This Court has jurisdiction under the terms of the United

States Supreme Court's remand in Houston Lawyers' Assn. v. Attorney

General of Texas, 111 S. Ct. 2376 (1991).

1

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

ISSUE PAGE

SECTION I: 9

What degree of deference should this court extend to the

district court's conclusion that the state's interest in

the present electoral scheme did not outweigh minority

interests in a more representative scheme? What is the

standard of review? Did the district court so find?

SECTION II: 11

What are the state's interests, if any, in maintaining

the present electoral scheme? Explain.

SECTION III: 18

Justice Steven's opinion for the court recognized the

state's interest in linking the geographical area for

which a trial judge is elected to its jurisdiction. The

court held that this interest was to be weighed in a

determination of liability. Please explain your position

regarding such an analysis. You should consider:

a) . 18

What does a court weigh the state's interest

in linkage against? Is it weighed against

found dilution? How?

b) . 20

Who bears the burden of proof? Does the

Burdine construct in Title VII cases offer a

usable model?

c) . 23

Does the weighing present a question of fact

or a question of law, or a mixed question?

That is, who decides?

SECTION IV: 24

Is the state's interest adequately weighed by inquiry

suggested by Ginqles? If not, what additional inquiry is

required to determine liability? Would inquiry into the

cause of racial bloc-voting (e. g. , inquiry into the

existence of straight-ticket voting) be relevant to this

post-Ginqles weighing of state's interest?

2

SECTION V: 26

If weighing of the state's interest takes place as a part

of the court's assessment of the "totality of the

circumstances," then how should the court weigh state's

interest with other Zimmer factors in order to determine

whether there is liability?

SECTION VI: 29

Given the state's interest in linkage, must a plaintiff

prove as an element of her claim that only changes in the

linkage (e. g. single member districts as opposed to

changes in rules governing single shot voting, and

majority runoff requirement) will remedy the dilution?

For example, if a majority runoff requirement is a

possible cause of dilution, must a plaintiff prove that

it was not or should it be for the state to prove? Is

there record evidence from which the court can determine

the relative contributions to any found dilution of the

distinct elements of the total electoral process; e. g.

any contribution to found dilution of majority run-off

requirements, designated positions, etc.?

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Course of Proceedings and Disposition Below

Pursuant to Rule 28, Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure,

Appellees do not disagree with the State Defendants-Appellants'

statement of the course of proceedings and disposition below as

stated in their Original Brief at pages 2-5, and Brief on Remand at

pages 2-3.

Statement of the Facts

District judges in Texas (trial level judges) run for four

year terms in partisan primaries, which have a majority vote

requirement. In the general election, a plurality of the vote

wins. Vacancies are filled by appointment by the governor. Each

candidate must file for a specific district court, which are

numbered. Each district is coincident with a county boundary

(except for the 72nd District Court which includes both Lubbock and

Crosby counties). Elections are at-large, county wide. The number

of district judges in the counties under attack varies from three

in Midland County to 59 in Harris County.

Jurisdiction of district courts is statewide. Nipper v. U-

Haul Co., 516 S.W.2d 467, 470 (Tex. Civ. App. 1974). Venue, on the

other hand, is provided by statute. Specialized courts (criminal,

domestic relations, juvenile, civil) are merely district courts

which are required by statute to give preference to certain types

of cases. Texas district judges have both decision making and

administrative roles. Administrative duties, such as making local

4

rules, are usually carried out in concert with other district

judges.

The Court's attention is called to the Original Brief of

Plaintiffs-Appellees, pp. 3-4, previously filed in this cause

regarding facts proved at trial. Plaintiffs-Appellees would also

call the Court's special attention to the original amicus brief

previously filed by the United States, pp. 2-12, for a full

statement of the Texas judicial system and district court decision.

5

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42. U. S. C. 1973, has

been determined by the Supreme Court to cover judicial elections.

The findings of the trial court regarding the strength of the

state's interest in continuing to elect district judges at-large

are factual findings subject review under the clearly erroneous

test of Rule 52(a), F. R. C. P. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U. S. 30

(1986). The Supreme Court decision in this case did not change

that standard of review. Further, it did not set a new standard

for evaluating the state's interest in the present electoral

scheme. Rather, it reaffirmed that a state's interest is merely

one of the factors to be considered in evaluating the "totality of

the circumstances" to make a vote dilution finding. Houston

Lawyers' Assn. v. Attorney General of Texas, 111 S. Ct. 2376 (1991)

The state has no compelling interest in maintaining the

present at-large electoral scheme. The basis of their argument

that at-large elections promote judicial integrity by linking

jurisdiction and electoral base is undercut by a factual

misstatement. There is no coincidence between a district court's

jurisdiction and the electoral base of the district judge.

District courts have jurisdiction statewide. Nipper v. U-Haul Co.,

516 S. W. 2d 467 (Tex. Civ. App. 1970). District judges are

elected by judicial district, which may be a county or a collection

of counties.

6

The practice in Texas is that judges do not preside only in

the area where they were elected. Justices of the Peace are

elected by sub-district, yet have jurisdiction countywide.

Visiting judges preside anywhere in the state. A case may be heard

by any district judge without regard to whether the litigants are

eligible voters in his judicial district.

Whatever state interest there may be in at-large judicial

elections is not weighed separately against a judicial finding of

vote dilution based upon the "totality of the circumstances."

Rather, state interest is one of the "totality" to be considered by

the trial court is reaching a factual finding of vote dilution.

Houston Lawyers' Assn. v. Attorney General of Texas, 111 S. Ct.

2376 (1991).

The burden of proof in vote dilution cases is upon the

plaintiff to produce evidence that the political processes leading

to nomination and election are not equally open to participation by

the minority group. Chisom v. Roemer, 111 S. Ct. 2354 (1991).

The question of state interest is a fact question to be given

proper deference by the reviewing court. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478

U. S. 30 (1986).

The asserted state interest is properly evaluated under the

"totality of the circumstances test." Houston Lawyers' Assn. v.

Attorney General of Texas, 111 S. Ct. 2376 (1991) . To inquire into

the cause of racial bloc voting is contrary to the Supreme Court's

7

direction in Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U. S. 30 (1986), and such

inquiry represents an attempt to reinject the intent standard into

vote dilution claims.

The question of a state's interest in at-large elections is of

relatively minor importance, and does not overcome a finding of

vote dilution. Senate Report, p. 29, n. 117. The most important

factors to be proved are the extent to which minority candidates

have been elected to office and the extent to which voting is

racially polarized. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U. S. 30 (1986).

A plaintiff need not prove the contribution of each aspect of

an at-large electoral system to the dilution of minority voting

strength. Vote dilution is a factual finding of the trial court

based upon the "totality of the circumstances" coupled with an

intense local appraisal of the operation of the electoral scheme in

question.

8

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES

SECTION I: What degree of deference should this court extend

to the district court's conclusion that the state's interest in the

present electoral scheme did not outweigh minority interests in a

more representative scheme? What is the standard of review? Did

the district court so find?

District Court Findings. The trial court outlined the State's

claims of its interest in the present at-large electoral scheme for

district judges. Finding of Fact No. 34, pp. 75-6, Memorandum and

Order of November 8, 1989:

1. Judges elected from smaller districts would be more

susceptible to undue influence by organized crime

2. Changes in the current system would result in costly

administrative changes for the District Clerk's office.

3. System of specialized courts in some counties would

disenfranchise all voters' rights to elect judges with

jurisdiction over some matters.

Although it did not find that the present system was

maintained on a tenuous basis as a pretext for discrimination, the

district judge was not persuaded that the reasons offered for its

continuation were compelling. Finding of Fact No. 37, pp. 77,

Memorandum and Order of November 8, 1989.

Appellants' Arguments. The State appellants have argued in

their most recent brief that the relative weight afforded these

interests is a legal question, and that the trial court's assertion

9

that these interests are not compelling is a conclusion of law.

Brief on Remand for State Defendants-Appellants, p. 17.

Appellant Entz asserts that no deference is due the trial

court's findings since the question of whether the state's interest

is compelling is a legal question. If the court finds that the

interests are not compelling, then it must consider them under the

"totality of the circumstances" test. Brief of Appellant Dallas

County District Judge F. Harold Entz, p. 2.

Appellees' Reply. This court is required by the holding of

the Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. 2752 (1986),

to defer to the trial court's factual finding that the state's

interest in the present electoral scheme is not compelling, absent

such finding being clearly erroneous. The ultimate finding of vote

dilution is a fact question subject to the clearly erroneous rule.

Thornburg v. Gingles, at 2781:

We reaffirm our view that the clearly-erroneous test of

Rule 52(a) is the appropriate standard for appellate

review of a finding of vote dilution.

Since the Supreme Court held that the question of a state's

interest is to be evaluated within the context of the "totality of

the circumstances," Houston Lawyers' Assn. v. Attorney General of

Texas, ill S. Ct. 2376, 2380 (1991) and the Court held in Gingles

that Rule 52(a) applies to the "totality of the circumstances"

evaluation, then that standard applies to this court's review of

the district court's findings.

10

Assuming, arguendo, that there is any compelling state

interest to be considered under the totality of the circumstances

test, then the finding regarding that interest is a factual

determination. In a Fourteenth Amendment context, assertions of

compelling state interest are factual findings to be made by the

trial court based upon "all relevant circumstances." Batson v.

Kentucky, 476 U. S. 79, 96-97 (1986). The state has the burden of

establishing the compelling nature of the state's interest with

actual proof, not just assertions and assumptions. Id. at 97. As

seen below, the state's avowal of its interest did not survive the

fact finding process of the trial court.

SECTION II: What are the state's interests, if any, in

maintaining the present electoral scheme? Explain.

District Court Findings. As stated in Section I above, the

trial court found that the state had posited freedom from undue

influence, administrative costs, and specialized courts as its

interests in maintaining the present at large system for election

of district judges.

Appellants' Arguments. The State has argued for the first

time on appeal that maintenance of judicial accountability and

judicial independence which in turn maintain judicial integrity is

the state interest at issue. It further posits that the method by

which this interest is fostered is by linking the jurisdictional

base of district judges directly to the electoral base. It alleges

11

that the common base is the same as the basic unit of Texas

government, the county, and that such linkage of jurisdictional and

electoral base is crucial. Brief on Remand for State Defendants-

Appellants, p. 17-18.

Appellant Entz has adopted the alleged linkage of elective

base and jurisdiction as the state interest, which presumably

justifies a strong presumption against radically changing the very

office of district judge. He further asserts that specialization

defines the office, and therefore is a compelling interest. Brief

of Appellant Dallas County District Judge F. Harold Entz, pp. 2,

14, 17.

Appellant Wood points to the state's fundamental political

decision to have trial judges who wield full judicial authority

alone, and to the historical preference of the citizens of Texas

for an elected judiciary in which each judge is accountable to each

voter and is independent from special interest groups. Wood also

notes that venue, jury selection pools, docket equalization, and

specialized court system are important state interests. Finally,

she asserts that the electoral district is coincident with the

supposed countywide jurisdictional district. Appellant Defendant-

Intervenor Harris County District Judge Sharolyn Wood's Brief on

Remand, p. 30-31.

12

Appellees' Reply.

Jurisdiction and Electoral Base. Each of the above set of

assertions, relying upon the alleged coincidence of electoral and

jurisdictional base to justify the at-large electoral scheme in the

face of proven discrimination, are based upon a misstatement of the

jurisdiction of Texas district courts. There is no concurrence

between jurisdiction and electoral base. District courts have

jurisdiction statewide. Nipper v. U-Haul Co., 516 S.W.2d 467, 470

(Tex. Civ. App. 1974) . District judges are elected from judicial

districts, which may be one or several counties.1

In addition, the concept of "primary jurisdiction," taken to

mean jurisdiction within the county, concocted by the appellants is

a fiction - there is no such thing. A court has or does not have

jurisdiction. There is no "primary" and "secondary" jurisdiction.

The relation of judicial districts to counties is

haphazard. There is an intricate web of overlapping districts, for

example:

3rd Judicial 87th Judicial 349th Judicial

District: District: District:

Anderson Co.

Henderson Co.

Houston Co.

Anderson Co.

Freestone Co.

Leon Co.

Limestone Co.

Anderson Co.

Houston Co.

Source: State Defendants' Exhibits 2 & 3.

13

Jurisdiction is determined by the Texas Constitution and

statutes.2 Venue, often confused with jurisdiction, is determined

by a complex set of statutes.3 The general venue rule is that a

case "shall be brought in the county in which all or part of the

cause of action accrued or in the county of defendant's residence

if defendant is a natural person."4 Some venue rules are

mandatory, for example, an action for mandamus against the head of

a department of the state government must be brought in Travis

County, the site of the state capital.5 There are many exceptions

to the general venue rule. Nowhere in any of the venue statutes is

venue tied to electoral base.

2 Article 5, Section 8, Texas Constitution: District Court

jurisdiction consists of exclusive, appellate and original

jurisdiction of all actions, proceedings, and remedies, except in

cases where exclusive, appellate or original jurisdiction may be

conferred by the Constitution or other law on some other court,

tribunal, or administrative body. District Court judges shall have

the power to issue writs necessary to enforce their jurisdiction.

The District Court shall have appellate jurisdiction and general

supervisory control over the County Commissioners Court, with such

exception and under such regulations as may be prescribed by law.

Texas Government Code, Sec. 24.007, Jurisdiction: The district

court has the jurisdiction provided by Article V, Section 8, of the

Texas Constitution.

Texas Government Code, Sec. 24.008, Other Jurisdiction: The

district court may hear and determine any cause that is cognizable

by courts of law or equity and may grant any relief that could be

granted by either courts of law or equity.

3 Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code, Ch. 15.

4 Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code, Sec. 15.001

5 Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code, Sec. 15.014

14

Jurisdiction and venue are to be distinguished. "Jurisdiction"

is the power of a court to decide a controversy between parties and

to render and enforce a judgment with respect thereto, while

"venue" is the proper place where that power is to be exercised.

Subject matter jurisdiction cannot be conferred by agreement and

exists by reason of authority vested in a court by the Constitution

and statutes. Garcia v. Dial, 596 S. W. 2d 524, 527 (Cr. App.

1980) Venue, on the other hand, may be conferred by agreement.

Furthermore, as a rule, jurisdiction may not be waived by the

parties, 7 2 Tex Jur 413, Venue, Sec. 2, whereas venue is so

ephemeral that, unless properly asserted, it may be waived.6 In

addition, in multi-county districts, a judge may act in a case in

any of the relevant counties regardless of where the case arose.7

By amending the state constitution in 1985, the voters of the

state delegated to the voters of each county the policy decision

whether a judicial district may be smaller than a county.8 Thus,

Texas Rules of Civil Procedure. Rule 86. Motion to

Transfer Venue.

1. Time to File. An objection to improper venue is waived if not

made by written motion filed prior to or concurrently with any

other plea, pleading or motion except a special appearance motion

provided for in Rule 120a. A written consent of the parties to

transfer the case to another county may be filed with the clerk of

the court at any time. ...

7 Texas Government Code, Section 24.017.

8 ...Judicial districts smaller in size than an entire county

may be created subsequent to a general election where a majority of

the persons voting on the proposition adopt the proposition "to

allow the division of ____ County into judicial districts composed

of parts of _____ County." ... Texas Constitution, Art. 5, Sec.

7a(i).

15

by leaving the decision up to county voters, the state as a whole

has abandoned whatever interest it may have had in its alleged

linkage between electoral base and jurisdiction.

The structure and practice of the Texas court system strongly

suggests that State of Texas has no interest in continuing at-large

judicial elections by county.

Justice of the Peace courts, which have jurisdiction over an

entire county, are elected from county subdistricts. Bradley v.

Swearingen, 525 S. W. 2d 280, 282 (Tex. Civ. App. 1975). Tex.

Const. Art. V, Sec. 18 & 19. Tex. Govt. Code, Sec. 27.031,

Jurisdiction.

State law authorizes a system of "visiting judges," which

practice allows retired judges to fill-in for elected judges when

docket conditions require. Texas Government Code, Ch. 75.101. A

litigant has no electoral recourse against a visiting judge. Reed

v. State, 500 S. W. 2d 137, 138 (Tex. Crim. App. 1973).

Aspects of any particular case may be heard by any judge

depending upon the docketing system in use; for example, in Harris

County there is a central docketing system which assigns hearings

to any available court.

Since the jurisdiction of the district courts is statewide,

and since Texas has decided to elect district judges from areas

smaller than the entire state, it has made the policy decision to

permit the appearance that lower court judges are accountable to

16

The notion that jurisdiction andonly part of the electorate.9

electoral base are tied together in order to facilitate judicial

integrity, or for any reason, is factually inaccurate. Thus the

state's basic argument for maintaining judicial integrity through

at-large elections has failed since it can prove neither that its

alleged interest is implicated in the challenged practice, Tashjian

v. Republican Party of Connecticut, 107 S. Ct. 544, 551 (1986),

nor that the practice advances such interest. Eu v. San Francisco

Cty. Democratic Cent. Com., 109 S. Ct. 1013, 1023 (1989).

Remedial Considerations. Even if the State's assertions

regarding judicial integrity are correct, remedies are available

which can protect these interests. Remedy is, first of all, a

state legislative decision which may embrace sub-districts along

with other options that will satisfy legitimate state interests:

smaller than a county multi-member districts, limited voting, or

cumulative voting. Jurisdiction and venue could remain unchanged.

As stated by Judge Johnson in his dissent, 914 F. 2d at 669, note

33:

Once again, the concurrence's asserted concern is

premised on the anticipated remedy — subdistricting.

While the Supreme Court, in Gingles, did indicate that a

"single-member district is generally the appropriate

standard against which to measure minority group

potential to elect," it did not mandate the imposition

of subdistricts to remedy every instance of illegal vote

dilution. The concurrence, by erroneously factoring in,

at the liability phase, concerns which may never be borne

9 League of United Latin Am. Citizens v. Clements, 902 F. 2d

293, 317 (5th Cir. 1990), Johnson, J., dissenting

17

out, refuses to properly acknowledge the intent of the

Voting Rights Act.

SECTION III: Justice Steven's opinion for the court

recognized the state's interest in linking the geographical area

for which a trial judge is elected to its jurisdiction. The court

held that this interest was to be weighed in a determination of

liability. Please explain your position regarding such an

analysis. You should consider:

a). What does a court weigh the state's interest in

linkage against? Is it weighed against found dilution?

How?

The Supreme Court. Justice Stevens wrote, Houston Lawyers'

Assn. v. Attorney General of Texas, 111 S. Ct. at 2380-81:

... Even if we assume, arguendo, that the State's

interest in electing judges on a district-wide basis may

preclude a remedy that involves redrawing boundaries or

subdividing districts, or may even preclude a finding

that vote dilution has occurred under the "totality of

the circumstances" in a particular case, that interest

does not justify excluding elections for single-member

offices from the coverage of the Sec. 2 results test.

Rather, such a state interest is a factor to be

considered by the court in evaluating whether evidence in

a particular case supports a finding of vote dilution

violation in an election for a single-member office.

...Rather we believe that the State's interest in

maintaining an electoral system - in this case, Texas,

interest in maintaining the link between a district

judge's jurisdiction and the area of residency of his or

her voters - is a legitimate factor to be considered by

court among the "totality of the circumstances" in

determining whether a Sec. 2 violation has occurred.

... Because the State's interests in maintaining the at-

large, district-wide electoral scheme for single-member

offices is merely one factor to be considered in

evaluating the "totality of the circumstance," that

interest does not automatically, and in every case,

outweigh proof of racial vote dilution.

18

Appellants' Arguments. The State has argued, Brief on Remand

for State Defendants-Appellants, p. 19, that a state's interest is

of "constitutional magnitude" and must be weighed only against a

competing constitutional interest.

Appellant Entz asserts that a compelling state interest would

"trump" what otherwise would be a Section 2 violation, and that

even if not compelling, the state's interest will override a mere

statutory violation. Brief of Appellant Dallas County District

Judge F. Harold Entz, pp. 2, 12.

Appellant Wood contends that any remedy is to be defended

against evidence that it intrudes upon the constitutional rights of

the state to structure its core functions. Appellant Defendant-

Intervenor Harris County District Judge Sharolyn Wood's Brief on

Remand, p. 36.

Appellees' Reply. Justice Stevens has stated explicitly that

a state's interest is "merely one of the factors" to be considered

in a "totality of the circumstances" analysis. As such it is

considered along with the other "typical factors." There is no

authority in Houston Lawyers' Assn. v. Attorney General of Texas,

111 S. Ct. 2376, for an analysis that posits state interest as a

rival to a determination that the Voting Rights Act has been

violated. The Supreme Court has simply reaffirmed the method of

analysis that this Circuit has long used: state policy underlying

the use of at-large districting is one factor to be considered to

19

prove the fact of dilution. "...[A]11 of these factors need not be

proved to obtain relief.” Zimmer v. KcKeithen, 485 F. 2d 1297,

1305 (5th Cir. 1973), en banc, aff'd. sub nom. East Carroll Parish

School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U. S. 636 (1976). It certainly is not

a threshold factor, as in Gingles, which must be proven to

establish a vote dilution case. Houston Lawyers' Assn. v. Attorney

General of Texas, 111 S. Ct. at 2380.

Appellants rely upon Gregory v. Ashcroft, 111 S. Ct. 2395

(1991), to suggest that the state has an interest of constitutional

magnitude in at-large elections for district judges. Gregory does

not apply. Gregory is a case of statutory interpretation: does the

Federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act apply to appointed

Missouri state judges? In accord with cited precedent that

requires a "plain statement" of Congressional intent to interfere

with a state's setting of qualifications for its own officials, the

Supreme Court decided that Congress had not made it "unmistakably

clear" that appointed judges were covered by the Act. In this

case, however, the Court decided that Congress had made it clear

that judicial elections are covered by the Voting Rights Act.

b) . Who bears the burden of proof? Does the Burdine

construct in Title VII cases offer a usable model?

Appellants' Arguments. The State has suggested a burden

shifting approach to the question of dilution. While the plaintiff

must prove the Gingles factors, and bears the ultimate burden in

establishing that the current election system results in a denial

20

of voting rights, such shifting suggests that the State need only

produce evidence of its interest in the maintenance of the system

and the non-discriminatory reasons for retaining the system. Brief

on Remand for State Defendants-Appellants, p. 24.

Appellant Entz, on the other hand, correctly states that the

Title VII model is not helpful because it would inhibit the

required assessment of the totality of the circumstances. Brief of

Appellant Dallas County District Judge F. Harold Entz, p. 2.

Appellees' Reply. A plaintiff's burden is to bring forward

evidence that a challenged election practice has resulted in the

denial or abridgment of the right to vote based on color or race.

Chisom v. Roemer, 111 S. Ct. 2354, 2363 (1991). A plaintiff must

"produce evidence to support findings that the political processes

leading to nomination and election were not equally open to

participation by the group in question - that its members had less

opportunity than did other residents to participate in the

political processes and to elect legislators [representatives] of

their choice." White v. Regester, 412 U. S. 755, 766 (1973);

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U. S. 124, 149-153 (1971).

One of the "totality of the circumstances" factors is the

state policy behind at-large elections. The legislative history to

the Voting Rights Act, Senate Report No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1982) , reprinted in 1982 D. S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 177,

(hereinafter, Senate Report) specifically warns that "even a

21

consistently applied practice premised on a racially neutral policy

could not negate a plaintiff's showing through other factors

[derived from Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra] that the challenged

practice denies minorities fair access to the process." Senate

Report at 29, n. 117.

This warning has been respected by courts reviewing the

question. U. S. v. Marengo Co. Com'n., 731 F. 2d 1546, 1571 (11th

Cir. 1984) :

Under an intent test, a strong state policy in favor of

at-large elections, for reasons other than race, is

evidence that the at-large system does not have a

discriminatory intent. On the other hand, a tenuous

explanation for at-large elections is circumstantial

evidence that the system is motivated by discriminatory

purposes. [Citations omitted]. State policy is less

important under the results test: "even a consistently

applied practice premised on a racially neutral policy

would not negate a plaintiff's showing through other

factors that the challenged practice denied minorities

fair access to the process. [Senate Report, at 29, n.

117]. But state policy is still relevant insofar as

intent is relevant to result: evidence that a voting

device was intended to discriminate is circumstantial

evidence that the device has as discriminatory result.

See Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. at 354-55. Moreover,

the tenuousness of the justification for a state policy

may indicate that the policy is unfair. Hendrix v.

Joseph, 559 F. 2d 1265, 1269-1270 (5th Cir. 1977).

In cases in which the jurisdiction allows a choice between an

at-large and district electoral system, as does Texas,10 then the

courts have routinely held that this factor is neutral. Bolden v.

City of Mobile, 423 F. Supp. 384 (S. D. Ala. 1976), affirmed 571 F.

2d 238 (5th Cir. 1978), reversed on other grounds, 446 U. S. 55

10 Texas Constitution, Art. 5, Sec. 7a(i)

22

(1980). Accord: Cross v. Baxter, 604 F. 2d 875, 884-85 (5th Cir.

1979); Hendrix v. Joseph, 559 F. 2d 1265, 1270 (5th Cir. 1977).

The court in Nevett v. Sides, 571 F. 2d 209, 224 (5th Cir. 1978)

held that "a tenuous state policy in favor of at-large districting

may constitute evidence that other, improper motivations lay behind

the enactment or maintenance of the plan." As noted by the Hendrix

court at 1269, "the manifestation of a state's policy toward the

at-large concept can most readily be found in the sum of its

statutory and judicial pronouncements." Texas has a long and

shameful history of denigration of minority voting rights. To

suggest that a state that produced such a plethora of

discriminatory laws lay aside such prejudice to endorse at-large

elections is unreasonable and irrational.

c) . Does the weighing present a question of fact or a

question of law, or a mixed question? That is, who

decides?

Appellants' Arguments. Both the State defendants, Brief on

Remand for State Defendants-Appellants, pp. 16-17, and Judge Entz,

Brief of Appellant Dallas County District Judge F. Harold Entz, p.

2, argue that the weighing of the state's interest in the at-large

electoral system is a legal question.

Appellees' Reply. Both are wrong. Since an ultimate finding

of vote dilution is a fact question subject to the clearly

erroneous rule, Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. at 2781, and

since the question of a state's interest is to be evaluated within

23

the context of the "totality of the circumstances," Houston

Lawyers' Assn. v. Attorney General of Texas, 111 S. Ct. 2376, 2380,

and since Rule 52(a) applies to "totality of the circumstances"

evaluation, then that standard applies to a consideration of the

state's interest.

SECTION IV: Is the state's interest adequately weighed by

inquiry suggested by Ginqles? If not, what additional inquiry is

required to determine liability? Would inquiry into the cause of

racial bloc-voting (e. g., inquiry into the existence of straight-

ticket voting) be relevant to this post-Gingles weighing of state's

interest?

a. State's Interests.

Appellants' Arguments. The State suggests that since the its

interest in at-large elections is of constitutional dimension, then

its interest is not adequately weighed by the Gingles inquiry.

Brief on Remand for State Defendants-Appellants, p. 14.

Judge Entz contends that the state's interest should be

considered an affirmative factor that mitigates against a finding

of discriminatory results, and, if compelling, prevents such a

finding. Brief of Appellant Dallas County District Judge F. Harold

Entz, p. 3.

Appellees' Reply. Since the question of a state's interest

arises under the scope of the Voting Rights Act, and since the

Supreme Court has determined that this question is to be considered

under the "totality of the circumstances" test, Houston Lawyers'

Assn. v. Attorney General of Texas, 111 S. Ct. at 2380, then its

24

interest is adequately considered by the Gingles inquiry. The

Supreme Court made it clear in Gingles that the inquiry set out in

that opinion goes to the "totality of the circumstances."

b. Causation.

Appellants' Arguments. The State suggests that courts should

inquire into the cause of racial bloc voting to determine whether

the targeted part of the electoral system caused the alleged

discrimination, or whether, instead, other factors cause it. Brief

on Remand for State Defendants-Appellants, p. 27.

Judge Entz believes that partisan voting patterns are not

relevant to a "totality of the circumstances" evaluation, rather,

that they are relevant to the question of whether polarized voting

exists. Brief of Appellant Dallas County District Judge F. Harold

Entz, p. 3.

Judge Wood says that partisan voting patterns better explain

the results in Texas judicial races than does racial voting. She

asserts, without authority, that Section 2 requires a plaintiff to

show that elections are dominated by racial politics. Appellant

Defendant-Intervenor Harris County District Judge Sharolyn Wood's

Brief on Remand, pp. 27-27.

Appellees' Reply. The Supreme Court has rejected inquiry into

causation. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U. S. 30, 62 (1986) . Its very

definition of racial bloc voting, "a consistent relationship

25

between the race of the voter and the way in which the voter votes"

or "black voters and white voters vote differently," precludes

inquiry into causation. Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. at 2768,

n. 21.

To interject a notion of causation into the inquiry of

polarized voting is simply an attempt to return the intent standard

to vote dilution analysis. To accept such an argument would be to

change the empirical inquiry from the question of whether

minorities and whites prefer different candidates to the question

of why a particular candidate wins or loses. In the latter case,

the analysis no longer addresses the issue Congress mandates be

considered: the extent to which voting is racially polarized.11

SECTION V: If weighing of the state's interest takes place

as a part of the court's assessment of the "totality of the

circumstances," then how should the court weigh state's interest

with other Zimmer factors in order to determine whether there is

liability?

Appellant's Arguments. Only Judge Entz has addressed this

question. He suggests that if the state's interest is not

compelling, then it should be considered as a part of the court's

overall assessment. Brief of Appellant Dallas County District

Judge F. Harold Entz, p. 3.

11 For a complete discussion of the issue of reinjecting the

intent standard, see: 28 Howard Law Journal No. 2, pp. 495-513,

1985, Engstrom, Richard L. , "The Reincarnation of the Intent

Standard: Federal Judges and At-Large Election Cases."

26

Appellees' Reply. Fortunately, the legislative history of the

Voting Rights Act, sheds light on the question. The history sets

several factors for court review, including state policy which is

listed as an "additional factor that in some cases ha[s] had

probative value." Note 117, p. 29, Senate Report, states:

If the procedure markedly departs from past practices or

from practices elsewhere in the jurisdiction, that bears

on the fairness of its impact. But even a consistently

applied practice premised on a racially neutral policy

would not negate a plaintiff's showing through other

factors that the challenged practice denies minorities

fair access to the process.

The courts have declared repeatedly that some of the typical

factors are more important than others.

"[R]ecognizing that some Senate Report factors are more

important to multimember district vote dilution claims than others

... effectuates the intent of Congress." Thornburg v. Gingles, 106

S. Ct. at 2765, n. 15. Of primary importance are:

1. The extent to which minority group

members have been elected to office

in the jurisdiction

2. The extent to which voting in the

elections of the jurisdiction has

been racially polarized

Placing importance upon electoral success and voting patterns

furthers the purpose of the Voting Rights Act to "correct an active

history of discrimination ... [and] deal with the accumulation of

discrimination. Latin American Citizens Council #4434 v. Clements,

914 F. 2d 620, 667, n. 31 (5th Cir. 1990), Johnson, J. , dissenting.

27

Furthermore, the legislative history concluded that some

factors are of less importance, including the tenuousness of the

state policy behind at-large judicial elections. "[I]n light of

the diminished importance this factor has under the results test,

8. Rep. No. 417 at 29 & n. 117, 1982 U. S. Code Cong. & Admin. News

at 2 07 & n. 117, we doubt that the tenuousness factor has any

probative value for evaluating the 'fairness' of the electoral

system's impact." Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F. 2d 364, at 383

(1984) .12

Finally, all the enhancing factors that the trial court found

in this case (at-large; lack of geographic sub-districts; a large

district; numbered posts; majority vote requirement; and staggered

terms) have been determined by prior decisions of this court to be

dilutionary. Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F. 2d 364, 383 (5th

Cir. 1984).

The factual determination of vote dilution is made based upon

an examination of all of these factors and intense local inquiry.

Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. at 2781 (1986).

The other less important factor is "unresponsiveness,"

which is no longer a necessary part of a plaintiff's case. Senate

Report 207, n. 116. Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U. S. 613, n. 9 (1982)

28

SECTION VI: Given the state's interest in linkage, must a

plaintiff prove as an element of her claim that only changes in the

linkage (e. g. single member districts as opposed to changes in

rules governing single shot voting, and majority run-off

requirement) will remedy the dilution? For example, if a majority

run-off requirement is a possible cause of dilution, must a

plaintiff prove that it was not or should it be for the state to

prove? Is there record evidence from which the court can determine

the relative contributions to any found dilution of the distinct

elements of the total electoral process; e. g. any contribution to

found dilution of majority run-off requirements, designated

positions, etc.?

Appellants' Arguments. The State maintained that plaintiffs

must prove that the challenged practice is the cause of the alleged

discrimination. Brief on Remand for State Defendants-Appellants, p.

27.

Judge Entz takes a similar position. He concedes that a

plaintiff should not have to negate all possible causes of

discrimination, but urges that a defendant may prove that something

else has caused the disparate result, and such proof would negate

a Section 2 violation. Brief of Appellant Dallas County District

Judge F. Harold Entz, p. 3.

Judge Wood only argues that proved dilution should be remedied

without great violence to state institutions. Appellant Defendant-

Intervenor Harris County District Judge Sharolyn Wood's Brief on

Remand, p. 29.

Appellees' Reply. There is no requirement that a plaintiff

prove that a particular aspect of an at-large election system has

prevented the political access of minorities. In this case, the

29

challenge was to the at-large election system for district judges.

No particular aspect of the extant system was singled out for

attack other than the at-large feature. Certain aspects of the

system were noted by the trial court as enhancing the proved

discrimination: numbered posts, majority rule requirement in

primary elections, and a large district in five of the targeted

counties. Finding of Fact No. 27, pp. 71-72; Conclusion of Law No.

15, p. 89. The courts have never required that a plaintiff

establish the contribution of each aspect of the election system to

the proved discrimination.13 Rather, Congress has found that these

factors enhance the tendency of the at-large system to submerge

minority voting strength. Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. at

2766, n. 15. This Court has noted that the existence of these

factors in an at-large election scheme aggravates its impact.'

"[I]ndirectly, these features 'inescapably' act as formal obstacles

to effective minority participation." Jones v. City of Lubbock,

727 F. 2d 364, 385 (5th Cir. 1984).

Once the trial court has found vote dilution, its duty is to

fashion relief so that it provides a complete remedy and fully

provides equal opportunity for minority citizens to participate and

to elect candidates of their choice. Senate Report, p. 31; Kirksey

v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F. 2d 139 (5th Cir. 1977) en banc,

cert, denied, 434 U. S. 968 (1977); Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727

13 Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. at 2770, notes that these

factors should be taken into account in establishing the amount of

white bloc voting that can generally minimize or cancel minority

voters' ability to elect candidates of their choice.

30

F. 2d at 386-387; Monroe v. City of Woodville, 819 F. 2d 507, 511,

n. 2 (5th Cir. 1987) ; Garza v. County of Los Angeles, 918 F. 2d

763, 776 (9th Cir. 1990).

At the remedy stage, if the proposed legislative plan includes

any of the enhancing factors, then the trial court should decide

whether the inclusion of that factor would prevent a complete

remedy. It "cannot blind itself to the effect of its districting

plan on racial groups." Jones, at 386. There is no place under

the results standard of Section 2 for requiring proof of causation

at the liability stage of a vote dilution case.

31

CONCLUSION

The Plaintiffs-Appellees, LULAC, et al., request that this

Court AFFIRM the order of the trial court which found that the at-

large system for electing Texas district judges in the targeted

counties violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, and REMAND

the case to the District Court for entry of a remedial plan.

Dated: October 3, 1991

Respectfully submitted,

ROLANDO L. RIOS

Southwest Voter Registration

Education Project

201 N. St. Mary's, Suite 521

San Antonio, TX 78205

512/ 222-2102

GARRETT & THOMPSON

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

A Partnership of

Professional Corporations

Attorneys for

Plaintiffs-Appellees

SUSAN FINKELSTEIN

Texas Rural Legal Aid, Inc.

405 N. St. Mary's, Suite 910

San Antonio, TX 78205

512/ 271-3807

Attorney for Christina Moreno

32

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned hereby certifies that a true and correct copy of

the foregoing instrument was served upon the all parties hereto b}

delivery to their attorneys of record by U. S. Mail,

prepaid, or by Federal Express, on Octoi

33

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

-- -oOo-—

HOWARD G. LEWIS, }

)

Petitioner, )

)vs, )

)

FRANK M» JORDAN, as Secretary Of )

The State of California, )

-)

Respondent, )

)and )

CALIFORNIA COMMITTEE FOR HOME )

PROTECTION; CALIFORNIA REAL )

ESTATE ASSOCIATION; CALIFORNIA )

APARTMENT HOUSE OWNERS )

ASSOCIATION; ROBERT A. OLIN; )

WILLIAM A. WALTERS, LAWRENCE )

H. WILSON, ROBERT L, SNELL, )

REG, F, DEPUY, DONALD McCLURE, )

Real Parties in Interest, )

_____________ )

PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDATE AND

POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT THEREOF

NATHANIEL 3. COLLEY

COLLEY AND McGHEE

1617 10th Street

Sacramento 14, California

LOREN MILLER

MILLER & MALONE

2824 South Western Avenue

Los Angeles, California

Steno Print & Mailing Service - Sacramento

SUBJECT INDEX

THE PETITION 1A

POINTS AND AUTHORITIES 2

INTRODUCTION 2

JURISDICTION 3

THE PARTIES 4

RELIEF SOUGHT 5

ARGUMENT

The Proposed Initiative Constitutional

Amendment Is Invalid Because The

Summary And Title Prepared By The

Attorney General Are Fatally Defective 6

The Proposal Would Violate the Fourteenth

Amendment To The United States

Constitution 12

The Proposal Represents An Unlawful

Attempt To Revise Rather Than Amend

The State Constitution 64

CASES

Abstract Investment Company vs. Hutchinson

204 Cal. App. 2d 255 (1962) 12 = 13

Banks vs. Housing Authority of San Francisco,

122 Cal. App. 2d 1 4

Banks vs. San Francisco, 122 Cal. App. 2d 1 20

Barrows vs. Jackson, 112 Cal. App. 2d 464 20

Barrows vs. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 40

Page

i

Billings v. Hall, 6 Cal. 1, 6 26-66

Boyd v. Jordan, 1 Cal. 2d 468 10-12

Burke v. Poppy Construction Co. ,

57 Cal. 2d 463 23-24

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 16-19-44

Caine v. Robbins., (Nev.) 131 Pac. ad. 516 73

City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 Fed.

2d 859 19

Clark v. Jordan, 7 Cal. 2d 248 10

Cooper v„ Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 14

Corsi v. Mail Handlers Union, 326 U.S. 88 24

Cummings v. Hokr, 31 Cal. 2d 844 19

Epperson v. Jordan, 12 Cal. 2d 61 12

Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261, 282 33

Gage v. Jordan, 23 Cal. 2d 749 8

Goss v. Board of Education, 10 L„ ed 636 16

Grandolfo v. Hartman, 59 Fed. 181 (1892) 19

Gwinn v. The U .S ., 238, U.S. 347 29

Hurdv. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948) 44

James v. Marinship, 25 Cal. 2d 721 24

Katzev v. Los Angeles, 52 Cal. 2d 360 69

L. A. Investment Company v. Gary,

181 Cal. 680 J 19

CASES - CONTINUED

Page

ii

Lane v„ Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 29-30

Lee Sing, 43 Fed. 359 (1890) 19

Livermore v. Waite, 102 Cal. 113, 117-119 64-73

Lombard v. Louisiana, 10 L0 Ed. 2d 33 8 15

McFadden v. Jordan, 32 Cal. 2d 330, 332 4-5-64

Miller v. McKenna, 23 Cal. 2d 774,

783 28-65-66

Ming v. Horgan, No. 97130, Sacramento

Superior Court 21

Minor v. Happerstett, 21 Wall. 162, 165-166 36

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U.S. 369 29

Nixon v. Condon, 286, U. S. 73 15-30

Perry v. Jordan, 34 Cal. 2d 87 4

Public Utilities Commission v. U. S.

355 U.S. 534 14

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi,

326 U.S. 88 15

Rice v. Elmore, 165 Fed. 2d 3 87 3 8

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 19-28-31-32-34

Smith v. Allenright, 321 U.S. 649 15-30

Slander v. West Virginia, 100 U.S.

303, 307 32-37-40

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378 14

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461

CASES - CONTINUED

Page

iii

15-38

CASES - CONTINUED

14

Page

Testa v. Katt, 330 U. S„ 386

Title Insurance v. Garrott, 42 Cal.

App» 152 54

U. S. v. Harris, 106 U. S. 629 25

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313, 317, 318 43

Williams v. Howard Johnson, et al.

268, Fed. 845 15

Windv. Hite, 58 Cal. 2d 415 72

Wirin v. Parker, 48 Cal. 2d 890 5-16

CODES

California Elections Code, Sec. 3501 6a

California Civil Code

Sec. 53 56

Sec. 382 4

Sec. 526A 5-16-73

Sec. 711 54

Sec. 728 (1961) 55

Sec. 1086 5

Sec. 2362 11a-53

Sec. 3386 50

Business & Professional Code, Chap. 3,

Art. 1 49

Health & Safety Code

Sec. 33049 (1959) 58

Sec. 33050 (1961) 62

Sec. 33070 (1961) 63

Probate Code, Sec. 1530, 1534 52

United States Code, Title 42, Sec. 1982 8a

iv

MISCELLANEOUS

Rules On Appeal, Rule 56 2a

Constitution of the State of California

Article I, Sec. 1 64-26-12a

Article I, Sec. 11 68

Article IV, Sec. 1 6a-47

Article XVIII, Sec. 2 64

Article XIX, Sec. 4, 1879 18

National Housing Act of 1934 9a

Sacramento Superior Court Action

No. 147,992 3

Weaver, Robert. The Negro Ghetto.

New York, Harper & Bros. 1948 21

Abrams, Charles. Forbidden Neighbors.

New York, Harper & Bros. , 1955 21

Woofter, T. J. Negro Problem in Cities,

New York, Double day-Doran. 21

Me Entire, Davis. Residence and Race.

Berkeley, University of California Press 21

U. S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Housing, 1961 Report. 21

Page

Report of the Commission on Race and

Housing. Where Shall We Live?

University of California Press, 1958 23

Harris, Robert J. The Quest for Equality.

Baton Rouge, L a ., Louisiana State

University Press, 160, p. 40, 41. 35

Graham, Howard Jay. Our Declaratory

Fourteenth Amendment. 7 Stanford Law

Review 3 (1954) ~ 36

v

MISCELLANEOUS - CONTINUED

Page

Franks John P„ and Munro, Robert F,

The Original Understanding of Equal

Protection of the Laws. 50 Columbia

Law ReviewT53T<[1950)" 36

vi

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

-_ -oO o---

HOWARD G„ LEWIS, )

)

Petitioner, )

)

vs„ )

)

FRANK M„ JORDAN, as Secretary Of )

The State of California, )

)

Respondent, )

)

And )

)

CALIFORNIA COMMITTEE FOR HOME )

PROTECTION; CALIFORNIA REAL )

ESTATE ASSOCIATION; CALIFORNIA )

APARTMENT HOUSE OWNERS )

ASSOCIATION; ROBERT A. OLIN; )

WILLIAM A, WALTERS, LAWRENCE )

H„ WILSON, ROBERT L. SNELL, )

REG, F, DEPUY, DONALD McCLURE, }

)

Real Parties in Interest, )

_____________ ______ _________________________ )

PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDATE AND

POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT THEREOF

TO THE HONORABLE CHIEF JUSTICE AND THE

ASSOCIATE JUSTICES OF THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA:

Petitioner HOWARD G. LEWIS, by this,

his verified petition, seeks a Writ of Mandate

la

commanding the respondent, FRANK M. JORDAN,

as Secretary of State of: the'State of-California, to

refrain from performing any act or duty as such

Secretary of State with respect to placing the herein

after referred to proposed initiative constitutional

amendment on the next general election ballot to be

voted upon by the people, and specifically to omit

said proposal, from said ballot.

In compliance with said subsection (a) of

Rule 56 of the Rules on Appeal, petitioner states that

in his opinion and in the opinion of his counsel the

writ should issue from this Honorable Court for the

following reasons:

(a) The question is one of great import

ance and urgency to all the people of the State of

California in that the contested proposal would effect

fundamental changes in the laws of this state. The

public interest would be served by an early determin

ation of the issues raised herein, and these issues

should be determined by a court of last resort.

(b) The time schedules for placing an

initiative proposal on the ballot are such that it would

not be practical to have the issues raised herein first

determined by a superior court and then on appeal in

2a

this Court, since said measure has qualified for a

place on the ballot at the next general election. The

ensuing campaign to defeat or adopt the contested

proposal will be extremely expensive for each side,

and will inevitably cause strife and division among the

people.

In further support of his petition petitioner

alleges:

I

That plaintiff is a member of an ethnic

group of persons commonly known and referred to as

Negroes; that plaintiff brings this action on behalf of

himself and others similarly situated with respect to

certain acts, practices and customs of defendants

more particularly hereinafter set forth; that there

are several hundreds of thousands of persons in

California belonging to the same ethnic group as

plaintiff, and who have an interest in this action; that

the number of persons constituting the legal class of

persons similarly situated with respect to certain

actions, plans, customs and practices of the real

parties in interest herein as will more particularly

hereinafter appear is so large that it is not practical

to bring all of them before the Court; that petitioner

3a

is willing and able to adequately represent the in

terests of all of said persons* and shall so represent

them.

In addition* plaintiff is a resident* citizen*

elector and taxpayer of the County of Sacramento*

State of California* and has become obligated to pay

and has paid real property taxes to said county within

one year last past.

II

That respondent* FRANK M. JORDAN* is

the duly elected qualified and acting Secretary of

State of the State of California* and is sued herein in

his official capacity.

III

That the real parties in interest herein are

the official sponsors or proponents of a certain pro

posed alleged initiative constitutional amendment

hereinafter referred to in detail. Said real parties

in interest are as follows:

(1) CALIFORNIA REAL ESTATE ASSOCI

ATION* is a California corporation* having individual

and corporate members who are engaged in the bus

iness of selling* renting* leasing, managing and

otherwise dealing in real property. Said real party

4a

in interest has over forty thousand members, and

represents a substantial portion of all the persons

engaged in the real estate business in this state.

(2) The CALIFORNIA APARTMENT HOUSE

OWNERS ASSOCIATION is a California corporation

whose members own and operate a substantial portion

of all the rental residential housing in this state.

(3) The CALIFORNIA COMMITTEE FOR

HOME PROTECTION is an unincorporated association

organized and existing for the sole purpose of sponsor

ing said proposed alleged constitutional amendment.

(4) The other persons named herein as

real parties in interest are sponsors or proponents of

said proposed alleged constitutional amendment,

either as individuals or as representatives of the other

real, parties in interest.

IV

That on or about November 6, 1963, the

real parties in interest herein, acting individually and

jointly as sponsors or proponents thereof, presented

to the Attorney General of the State of California a

request to give a title and summary to a proposed

alleged Initiative constitutional amendment herein

referred to; that a true copy of said request is marked

5a

"Exhibit A" and annexed hereto and made a part

hereof for all purposes; that said request was made

pursuant to the provisions of Section 3501 of the

California Elections Code.

V

That on or about November 7, 1963, the

s aid Attorney General prepared and delivered to the

real parties in interest herein, and to the respondent

an alleged title and summary of said proposal, A

true copy of said title and summary is marked

"Exhibit B" and annexed hereto and made a part

hereof for all purposes; that in preparing and sub

mitting said title and summary the said Attorney

General was acting pursuant to the provisions of

Article IV, Section I of the Constitution of the State

of California,

VI

That the chief purpose of said proposal is

and always has been to nullify certain laws enacted

by the legislature of California to prevent racial and

religious discrimination in the sale, rental and use

of publicly assisted residential housing; (See "Exhibit

C" annexed hereto); that the real parties in interest

did not at any time inform the said Attorney General

6a

what the chief purpose of the proposal is, but as soon

as the said title and summary were prepared and

delivered as required by law, the real parties in

interest themselves prepared a document which they

entitled "Statement of Purposes, " a true copy of

which document is marked "Exhibit D" and annexed

hereto and made a part hereof for all purposes; that

a true copy of the proposal is marked "Exhibit E"

and annexed hereto and made a part hereof for all

purposes.

BII

That the real parties in interest herein

have circulated or caused to be circulated thousands

of petitions throughout the State of California seeking

the signatures of registered voters on said petition

so as to qualify the same for a place on the ballot at

the next general election; that respondent FRANK M,

JORDAN has received from the various clerks of the

several counties in this state certification that over

500, 000 such signatures have been secured, counted

and verified, and respondent fully intends to place

said proposal on the ballot at the next general election

unless restrained by order of this court.

7a

VIII

That in order to place said proposal on

said ballot respondent will be required to spend sub-

stantial sums of public funds and resources for print

ing and other costs.

IX

That said proposal should not be assigned

to a place on said ballot for the reason that the real

parties in interest have not complied with, the pro

cedural requirements specified in the laws of this

state, and for the further reason that said proposal

violates the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States. In support of these contentions

petitioner further alleges:

(a) That the title and summary as prepared

by the Attorney General of the State of California do

not state the true chief purpose or points of said

proposal as required by Article IV, Section I of the

California Constitution.

(b) That the proposed alleged initiative