Rodgers v Teitelbaum Motion for A Stay and for Relief Pendente Lite

Public Court Documents

November 2, 1976

8 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rodgers v Teitelbaum Motion for A Stay and for Relief Pendente Lite, 1976. 4a1d7cdb-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ca42efde-12e6-4195-a9ed-b3f7c631a62b/rodgers-v-teitelbaum-motion-for-a-stay-and-for-relief-pendente-lite. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

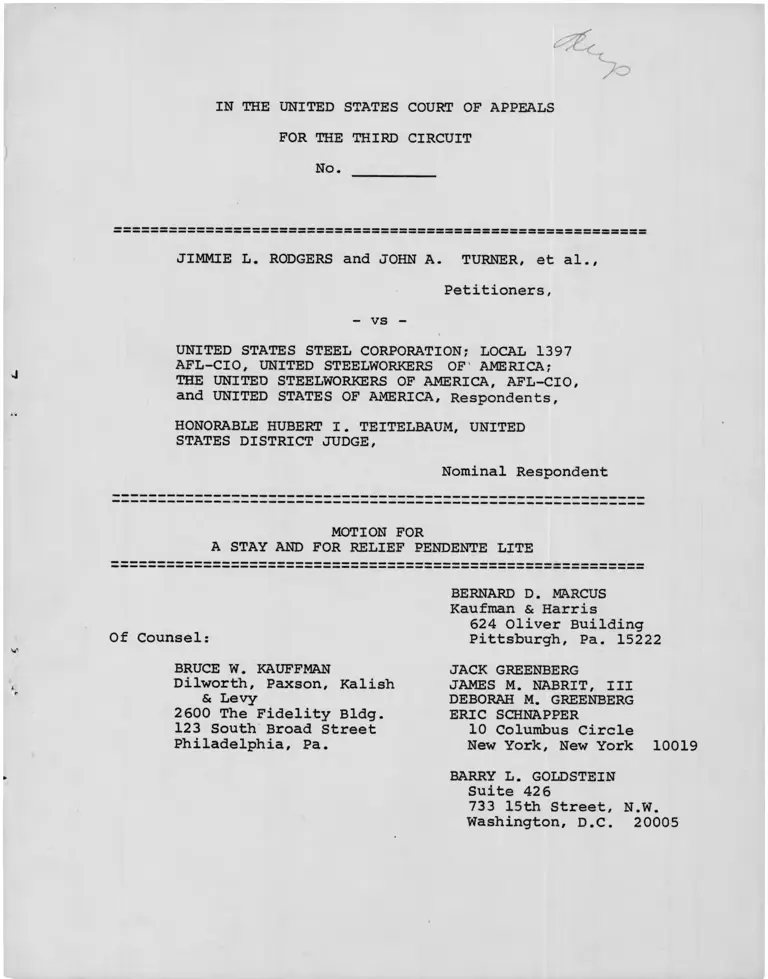

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

No.

JIMMIE L. RODGERS and JOHN A. TURNER, et al.,

Petitioners,

- vs -

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION; LOCAL 1397

AFL-CIO, UNITED STEELWORKERS OF' AMERICA;

THE UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO,

and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondents,

HONORABLE HUBERT I. TEITELBAUM, UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE,

Nominal Respondent

MOTION FOR

A STAY AND FOR RELIEF PENDENTE LITE

Of Counsel:

BRUCE W. KAUFFMAN

Dilworth, Paxson, Kalish

& Levy

2600 The Fidelity Bldg.

123 South Broad Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

BERNARD D. MARCUS

Kaufman & Harris

624 Oliver Building

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III DEBORAH M. GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

Suite 426

733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

NO.

JIMMIE L. RODGERS and JOHN A. TURNER, et al.,

Petitioners,

- vs -

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION; LOCAL 1397

AFL-CIO, UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA;

THE UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO,

and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondents,

HONORABLE HUBERT I. TEITELBAUM, UNITED

STATES DISTRIC JUDGE,

Nominal Respondent

MOTION FOR

A STAY AND FOR RELIEF PENDENTE LITE

Petitioners hereby move this Court for an order

staying, or vacating pendente lite, the November 2, 1976,

order of the United States District Court for the Western

District of Pennsylvania permitting the defendant United

States Steel Corporation to serve interrogatories on 509

class members in this case.

This action, alleging that the defendants United

States Steel Corporation and the United Steelworkers of

America have engaged in systematic racial discrimination in

violation of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights, was filed

in 1971. Plaintiffs first moved for class action certifi

cation in May 1973, and their motion was finally granted

by order dated December 9, 1975. While plaintiffs enga

ged in extensive discovery, the defendant company and union

never served on the plaintiff class representatives any

interrogatories, requests for admissions, or requests for

production of documents. The sole discovery heretofore

sought by the defendants was to depose, in 1973, the two

named plaintiffs; the questions asked by counsel for

defendants at these depositions were limited to the indivi

dual claims of the plaintiffs. On January 26, 1976, the

District Court established December 31, 1976 as the cut-off

date for all discovery.

On October 13, 1976, counsel for the defendant

Company informed counsel for plaintiffs that they intended

to serve a forty-page set of interrogatories, containing 28

questions, with over 140 sub-parts, and requiring the produc

tion of 10 different types of documents. The interrogatories

were concerned with the detailed circumstances of each class

member, and contemplated that a separate set of answers would

be prepared for each of the 509 class members as to whom

information was sought. Pp 13a-53a. The company proposed that

the 20,360 pages of answers to interrogatories, including

responses to 71,260 subquestions, be filed within 30 days.

Counsel for the company indicated their intention to serve

these interrogatories, not on counsel for the class, but by

certified mail directly on each of the 509 class members as

to whom the information was sought. P. 54a.

2

On October 22, 1976, counsel for plaintiffs

moved for a protective order and for an order deferring

answers regarding individual claims until after trial on

liability. Pp.55a-73a. The District Court denied these

motions and granted the Company's motion to serve the inter

rogatories (pp. 10 a-12a) on November 2, 1976, but granted

plaintiffs an ..additional 60 days to answer the interrogato

ries. Pp.101a-102a. Thereafter counsel for U.S. Steel

sought express approval by the Distric Court of its proposal

to serve the interrogatories directly on the individual class

members, rather than on the attorney representing the class.

Pp.104a-107a. On November 9, 1976, Judge Teitelbaum indica

ted that he had approved such service in his November 2 order.

P.113a. Plaintiffs immediately sought a stay of the

November 2 order pending application to this Court for a writ

of mandamus. Pp.120a-121a. Judge Teitelbaum denied the re

quested stay on November 22, 1976. P.150a.

Petitioners have already filed with this Court a

Petition for a Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition. Peti

tioners request that, pending resolution of that Petition,

the Court stay Judge Teitelbaum's order of November 2 permit

ting the service of the disputed interrogatories.

Petitioners maintain that it is highly likely that

the writ will be granted. The proposed service of the inter

rogatories on the individual class members, rather than on

their counsel, is an unprecedented and unwarranted attempt

by the company and District Court to interfere with the res

ponsibility of counsel to advise and represent those clients.

3

This Court has twice found it necessary to issue writs of

mandamus to the same judge in this very case to prevent

similar interference. Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp.,

508 F .2d 152 (3d Cir. 1975), cert, denied 420 U.S. 969 (1975);

Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp., 536 F. 2d 1001 (3d Cir.

1976). Even if the interrogatories were served on counsel,

the requirement that plaintiffs answer 71,260 written ques

tions regarding individual claims is unauthorized by law.

For the reasons set out in detail in the Petition,

the November 2 order was an abuse of discretion and beyond

the power of the District Court.

The service of the disputed interrogatories would

clearly cause irreparable injury to plaintiffs and the class

members involved. The class members would have to expend

literally thousands of hours preparing answers to the 140

subquestions posed to each and collecting, in most cases from

the defendants, the thousands of documents involved. The

Federal Rules encompass no clear remedy for the enormous amount

of time and energy that will be wasted if the interrogatories

are subsequently disapproved. Any attempt by counsel to

assist in this process is, of course, doomed to failure, since

the 71,260 questions would require over 1000 answers be

drafted every working day; any good faith though vain effort

would require that plaintiff's counsel abandon all of their

legal responsibilities for 3 months. It is at best unclear

whether the thousands of attorney hours thus wasted could be

compensated if the plaintiffs, though successful in demon

strating the interrogatories were improper, do not prevail on

4

the merits. To the extent that, in answer to these interro

gatories, class members divulge privileged matters or other

information to which the defendants were not entitled, the

subsequent proceedings would become a quagmire of problems

about the extent to which any defenses were thus tainted.

Moreover, the service of these burdensome interrogatories,

which on their face include the name and apparent approval of

counsel for plaintiff, p,15a, will cast an irrevocable pall

over future relations between counsel and the class, and reduce

the willingness of class members to provide counsel with tes

timony or necessary information.

These interrogatories, coming from the class members'

employer are bound to intimidate the black steelworkers on

whom they are to be served. Class members are warned that

"[f]ailure to answer these interrogatories can result in the

imposition of sanctions by the Court, including, but not limited

to, the dismissal of any claims" of the class member. Pp.l5a-16a.

(Emphasis added). What the limits are is left to each class

member's imagination. This harassment of the plaintiff class,

and the interference with counsel's preparation of their case

which is bound to result from requests for assistance from the

class members (see p,15a), constitute so profound interference

with the conduct of plaintiff's litigation as to impair their

1/ Petitioners maintain that such an award of counsel fees

would be required at once, and regardless of the final

outcome of the case, in view of the manifest bad faith

of this discovery request.

1/

5

First Amendment rights to associate for the purpose of con

ducting civil rights litigation, NAACP v. Button 371 U.S. 415

(1963). Such a violation of the constitutional rights of

plaintiffs and their class is, in itself, irreparable injury.

The service of these interrogatories would entail

as well a number of problems which may, in the most techni

cal of senses, be reparable. If class members are dismissed

for failing to answer — at all, completely, or well — the

interrogatories, they can and must later be reinstated if

the interrogatories are disapproved. Any "evidence" or

"admissions" disclosed by class members thus deprived of the

assistance of counsel could and must be declared inadmissible.

The considerable cost of xeroxing, notarizing and mailing the

5 copies of the 40 page interrogatories and all the documents

requested, about $30 for each class member, or a total of

approximately $15,000, would of course have to be refunded if

the writ is ultimately granted. The vast administrative

problems required to repair injuries of this sort should not,

we believe, be needlessly incurred.

In opposing the stay in the District Court the

company made no claim that a stay of the disputed discovery

would work any irreparable injury on it. Pp.144a-145a. The

company argued, however, that if the service of the interro

gatories were delayed it would require additional time to

prepare for trial. If the requested stay is granted

petitioners would, of course, agree to any extension of time

for the defendants which might be necessitated by that stay.

6

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons an order should issue

staying the order of the District Court insofar as it

permits service of the disputed interrogatories.

Respectfully submitted,

BERNARD D. MARCUS'/

KAUFMAN & HARRIS//

415 Oliver Building

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

DEBORAH M. GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

Suite 426

733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Petitioners

Of Counsel:

BRUCE W. KAUFFMAN

Dilworth, Paxson, Kalish

& Levy

2600 The Fidelity Building

123 South Broad Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

7