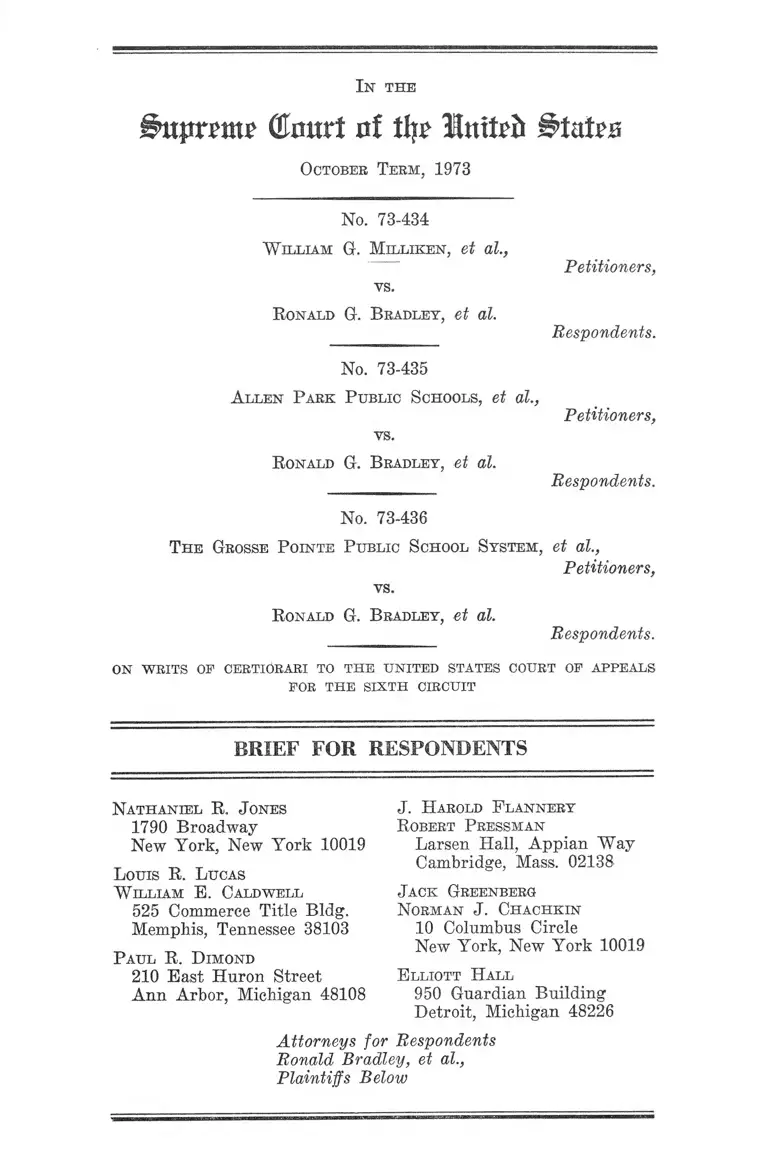

Milliken v. Bradley Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Milliken v. Bradley Brief for Respondents, 1973. 3e7c05ca-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ca6505cc-d2ec-4723-b786-b88ee349e362/milliken-v-bradley-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

^npxmt dmtrt nf % Ituteii States

October Term, 1973

No. 73-434

W illiam G. Milliken, et al.,

vs.

Bonald G. Bradley, et al.

Petitioners,

Respondents.

No. 73-435

A llen Park Public Schools, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

Bonald G. Bradley, et al.

Respondents.

No. 73-436

The Grosse Points Public School System, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

Bonald G. Bradley, et al.

Respondents.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Nathaniel B. Jones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Louis B. Lucas

W illiam E. Caldwell

525 Commerce Title Bldg.

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Paul B. D imond

210 East Huron Street

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48108

J. Harold Flannery

Eobert Pressman

Larsen Hall, Appian Way

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

Jack Greenberg

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Elliott Hall

950 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Respondents

Ronald Bradley, et al.,

Plaintiffs Below

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities ........................... ..........................-.... iii

Questions Presented .................................. .............. ........ 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 2

Counter-Statement of the Case ...................................... 2

A. Nature of Review ...... ........ ............ ........ ...... .... 2

B. The Proceedings Below .................................. . 11

1. Preliminary Proceedings ......... ........... ......... 11

2. Hearings on Constitutional Violation ... ..... 16

3. Remedial Proceedings .............. ...................... 19

a. The Practicalities of the Local Situation 19

b. The District Court’s Guidance by Settled

Equitable Principles and Its Order to

Submit Plans .............................. ................ 23

c. The Procedural Status of Suburban

Intervenors ........ ....................... ...... ......... 26

d. Hearings and Decision on Plans Limited

to the DSD ................................ .............. . 27

e. The Hearings and Decision on “Metro

politan” Plans ........... ...............................- 28

4. Appellate Proceedings ............................ 32

5. Proceedings on Remand ................. ............... 37

Summary of Argum ent............ ...... ................................... 38

PAGE

11

A rgument—

I. Introduction ...... .......... ............ ........ ..... ............... . 40

II. The Nature and Scope of the School Segrega

tion of Black Children by the Detroit and State

Authorities Provided the Correct Framework

for the Lower Court’s Consideration of Relief

Extending Beyond the Geographic Limits of the

Detroit School District ..................... ...... .............. 43

III. Based Upon Their Power and Duty to Achieve

a Complete and Effective Remedy for the Viola

tion Found, Taking Into Account the Practical

ities of the Situation, the Courts Below Were

Correct in Requiring Interdistrict Desegrega

PAGE

tion ...................................... .......... ............................ 53

IV. The Actions by the Lower Courts to Date Have-

Not Violated Any Federally Guaranteed Pro

cedural Right of Suburban School Districts ....... 61

A. In the Circumstances of this Case, Rule 19

and Traditional Principles of Equity Juris

prudence Do Not Require the Joinder of

Several Hundred Local Officials Where the

Parties Already Before the Court Can Grant

Effective Relief and There Remains a Sub

stantial Uncertainty Whether and How Their

Interests Will Be Affected, I f At A l l .......... . 67

B. Petitioner and Amici -School Districts Have

Not Been Denied Any Procedural Rights

Guaranteed to Them By the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments ...... ............ ........... ............ 74

Conclusion ............ ......... ....... .......... .................................. ...... 78

Note on F orm oe R ecord Citations ............ ............ ......... 80

I l l

T able of A uthorities

Cases: page

Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F. Supp. 220 (E.D. Ark. 1957),

aff’d sub nom. Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d 797

(8th Cir. 1958) ________ ______ _____________ ______ 71n

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19

(1969) .................. .......... ........ ...... ............. ................ 24n, 27

American Const. Co. v. Jacksonville T. & K. 14. Co.,

148 U.S. 372 (1893) ......... .... ...... .............................13n, 43n

Attorney General v. Lowery, 131 Mich. 639 (1902),

aff’d 199 U.S. 233 (1905) ......... ....... ............... _...8n, 71, 76n

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ................. .............. 51

Berry v. School Dist. of Benton Harbor, Civ. No. 9

(W.D. Mich. February 3, 1970) .................................. 22n

Bradley v. Milliken, 468 F.2d 902 (6th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 409 U.S. 844 (1972) ........ .............. ....................... 25n

Bradley v. Milliken, 438 F.2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971) ..... . 15

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970) ....... 15

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 462 F.2d 1058 (4th

Cir. 1972), aff’d by equally divided Court, 412 U.S.

92 (1973) ........................................................... 19n, 60n, 61n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 51 F.R.D. 139

(E.D. Ya. 1970) .............. ........ .................................... 75

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir.

1968) --------------------- ------- ------ -------------- ----------------- 8n

Broughton v. Pensacola, 93 U.S. 266 (1876) .............. 8n

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ____Passim

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ....... 3,5,

13n, 40, 59

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820 (4th Cir.

1970) ................................................................................. 30n

Carrington v. Rash, 380 U.S. 89 (1965) 58

IV

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S.

290 (1970) ................................................ ....................... 24n

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dist.,

467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 37 L.Ed.2d

1041, 1044 (1973) ............................................................ 7n

City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973) ....... . 76n

City of New Orleans v. New Orleans Water Works Co.,

142 U.S. 79 (1891) .......................................................... 77n

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ......... ....... ......... 3

Commanche County v. Lewis, 133 U.S. 198 (1890) .... 8n

Comstock v. Croup of Inst’l Investors, 335 U.S. 211

(1948) .......... .............. ........... ....... ..................... ............. 43n

Connecticut Gen’l Life Ins. Co. v. Johnson, 303 U.S.

77 (1938) .......................................................................... 76n

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) .......8n, 42n, 49, 50n, 64n

Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs, 402 U.S. 33 (1971) 5,

10, 23, 41

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 443 F.2d 573 (6th

Cir.), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 913 (1971) __________ 8n

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp. 734

(E.D. Mich. 1970), aff’d 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir.), cert.

denied, 402 U.S. 913 (1971) _________ _____________ 22n

Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir.

1966), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967) ..................... 45

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1856) 3

Edgar v. United States, 404 U.S. 1206 (1971) ............. 49n

Essex Public Road Bd. v. Skinkle, 140 U.S. 334 (1891).. 77n

Evans v. Buchanan, 281 F.2d 385 (3d Cir. 1960) ____ 66

Evans v. Buchanan, 256 F.2d 688 (3d Cir. 1958) ....56, 66, 71

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) ...........3, 8n, 41n, 55

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) ........ .............. ..... 49n

PAGE

V

PAGE

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ................. 8n

Graham v. Folsom, 200 U.S. 248 (1906) .................. . 8n

Graver Mfg. Co. v. Linde Co., 336 TJ.S. 271 (1948)....13n, 43n

Green v. County School Bd., 391 TJ.S. 430 (1968) .......5, 7n,

10, 41, 47, 55

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218" (1964) ....................... ............. 50, 70, 71n, 74n

Griffin v. State Bd. of Educ., 239 F. Snpp. 560 (E.D.

Yn. 1965) ................................ ........................ .............. 32, 71

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1939) .......... .................... 77

Haycraft v. Bd. of Educ. of Louisville, No. 73-1408

(6th Cir., Dec. 28, 1973) ...... ........................................ 48n

Higgins v. Grand Rapids Bd. of Educ., Civ. No. 6386

(W.D. Mich. 1973) ........ .......... ...... ......... ..... .......... . 22n

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 359 F. Supp.

807 (W.D. Pa. 1973) ............. .......... .......... ..... 56, 66, 70, 71

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) ....................... 14n

Hunter v. Pittsburgh, 207 U.S. 161 (1907) .... ....... ...71, 76

Husbands v. Commonwealth o f Pennsylvania, 359 F.

Supp. 925 (E.D. Pa. 1973) ........... .............................70, 71

James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137 (1971) ......... ............... 59

Kelly v. Guinn, 456 F.2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972), cert, de

nied, 37 L.Ed.2d 1041 (1973) .... ...... ........... ........ . 7n

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463 F.2d

732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972)....42, 62n

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ,, Civ. No.

2094 (M.D. Tenn., June 28, 1971), aff’d 463 F.2d 732

6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S.1001 (1972) ___ __ 31n

Kentucky v. Indiana, 281 U.S. 163 (1930) ....... ......... . 72

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 37 L.Ed.2d

548 (1973) ....— .... ................ ...... ........ .................... Passim

V I

Lane v. Wilson, 307 TT.S. 268 (1939) .... ....................... 14n

Lau v. Nichols, 42 U.S.L.W. 4165 (Jan. 12, 1974) .... . 65n

Lee v. Macon County Bd, of Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458

(M.D. Ala.), aff’d per curiam 389 U.8. 215 (1967) .... 66

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D.N.Y.), aff’d. per

curiam, 402 U.S. 935 (1971) .................................... . 14n

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 240 F. Supp. 709

(W.D. La. 1965), aff’d 370 F.2d 847 (5th Cir. 1967).... 65n

Marbury v. Madison, 5 TT.S. (1 Cr.) 137 (1803) ........... 78

Mobile v. Watson, 116 U.S. 289 (1886) ....... ...... ......... . 8n

Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs, 391 TT.S. 450 (1968) ..... 10

Mount Pleasant v. Beckwith, 100 TT.S. 514 (1879) ....... 8n

NAACP and Taylor v. Lansing Bd. of Educ.,------ F.

Supp.------ (W.D. Mich. 1973) ...................................... . 22n

Neal v. Delaware, 103 TT.S. 386 (1881) .................... ...... 3

Newburg Area Council, Inc. v. Bd. of Educ. of Jeffer

son County, No. 73-1403 (6th Cir., December 28,1973) 48n

New Jersey v. New York, 345 TT.S. 369 (1953) ......... 72, 77n

Northwestern Nat’l Life Ins. Co. v. Biggs, 203 TT.S. 243

(1906) ....... ......... ...... ..................... .................................. 78

Oliver v. School Dist. of Kalamazoo, 346 F. Supp. 766

(W.D. Mich.), aff’d 418 F.2d 635 (6th Cir. 1971),

on remand, Civ. No. K-98-71 (Oct. 4, 1973) ........ ...... 22n

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 TT.S. 537 (1896) .......3, lOn, lln , 78

Provident Bank v. Patterson, 390 TT.S. 102 (1968)..68n, 69n

Raney v. Board of Educ., 391 U.S. 443 (1968) ....... ..... 10

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ...................... 8n, 55

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 330 F. Supp.

837 (W.D. Tenn. 1971), aff’d 467 F.2d 1187 (6th

Cir. 1972) ........................................ ...............................70n

PAGE

vii

San Antonio Independent School Dist. v. Rodriguez,

411 II.S. 1 (1973) .......... ......................... .............. _.__58n, 59

Santa Clara County v. Southern R Co., 118 II.S. 394

(1886) ......... ...................... ............ ...................... ............ 76n

School Dist. of Ferndale v. HEW, No. 72-1512 (6th

Cir., March 1,1973) ........... ....... ........ ....... ....... ....... 20n, 22n

Schrader v. Selective Service System Local Bd. No. 76,

329 F. Supp. 966 (W.D. Wis. 1971) ......... ................ 64n

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) __________ 59

Shapleigh v. San Angelo, 167 U.S. 646 (1897) ..... ......... 8n

Slaughter House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873) .. 3

Sloan v. Tenth School Dist., 433 F.2d 587 (6th Cir.

1970) .................. ........... ....... ................. ......................... 8n

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) .... 76

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F. Supp.

501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) ................ .......... .....................1... 8n

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D.N.J. 1971),

aff’d per curiam 404 U.S. 1027 (1972) ............. ..... 42n, 59

Stamps and United States v. Detroit Edison Co., 365

F. Supp. 87 (E.D. Mich. 1973) .................................. 7n

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ...... . 3

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969) .. 33n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1 (1971) ..... ...................................................... ........... passim

Trenton v. New Jersey, 262 U.S. 182 (1923) ............ ..... 77

Turner v. Warren County Bd. of Educ,, 313 F. Supp.

380 (E.D.N.C. 1970) _____________________ ____ _______ 49n

United States v. Board of School Comm’rs of Indian

apolis, 474 F.2d 82 (7th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 37

L.Ed.2d 1041 (1973) ................ ........ ............... ............. 8n

United States v. Georgia, 466 F.2d 197 (5th Cir.

1972) ___________________ ______ ___________ 66, 70n, 74n

PAGE

V l l l

United States v. Georgia, 445 F.2d 303 (5th. Cir.

1971) ................................................................................. 66

United States v. Georgia, 428 F.2d 377 (5th Cir.

1970) ........... ........ ...................... ....................................... 66

United States v. Johnston, 268 U.S. 220 (1925) ....... 13n, 43n

United States v. School Dist. 151, 404 F.2d 1125 (7th

Cir. 1968) .............................. ............................ .............. 8n

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ., 407

U.S. 484 (1972) ................ ...................... ...........49, 54n, 58n

United States v. State of Missouri, 363 F. Supp. 739

(E.D. Mo. 1973) ............... ..... ..................... ................... 55

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 321 F. Supp.

1043 (E.D. Tex. 1970), 330 F. Supp. 235 (E.D. Tex.

1971) , aff’d sub nom. United States v. State of Texas,

447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971), stay denied, 404 U.S.

1206 (Black, J.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 1016 (1971)..66,70

PAGE

Welling v. Livonia Bd. of Educ., 382 Mich. 620 (1969).... 65

Western Turf Ass’n v. Greenberg, 204 U.S. 359 (1907).. 77

Wheeling Steel Corp. v. Glander, 377 U.S. 562 (1949).... 76n

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971)...................... 59

White v. Regester, 37 L.Ed.2d 314 (1973).................... 59

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) ....... ......... .......................... .....10,13n, 48, 54n, 58n, 59

Constitution and Statutes:

U.S. Const., Amend. 5 .......... ............................................ 75

U.S. Const., Amend. 14 .................................................... . 75

28 U.S.C. §1292 .............................. ............... ..................... 33

28 U.S.C. §1331 (a) .......... .............. ....... .............. ............. . 11

28 U.S.C. §1343 .................................................... ............... 11

IX

PAGE

28 U.S.C. §§2201, 2202 ........... ............................................. 11

42 U.S.C. §1981....... ....................... ............................. ....... 2,11

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................................. .............. 2,11, 76n

42 U.S.C. §1988 .... .............................................. ......... 2,11, 33n

42 U.S.C. §2000d........... ...............................................2,11, 65n

Mich. Const. Art. I, § 2 ........................ „ ........................... . 65

Mich. Const. Art. VIII, §3 65

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

M.C.L.A.

§340.69 ...............

§340.121 (d) ......

§340.183 et seq. .

§252-53 .............

§340.302a et seq.

§340.355 ...........

§340.582 ............

§340.583 ............

§340.589 ........ .

§340.1359 ..........

57n

57n

58n

65

58n

65

57n

52n

52n

58n

§340.1582 ......................... 58n

§388.171a et seq. (Public Act 48 of 1970) ..... 51

§388.681 ..................... 58n

§388.851 ................................................... 65

§388.1010 ............ .................... .......................20n, 65

§388.1117 .............................................. 65

§388.1234 ........ 65

X

F.R. Civ. P. 19 ............................................ ........... ..... 32, 37, 67

F.R. Civ. P. 2 1 ................................... ...... ........... ....... 32, 37, 68

F.R. Civ. P. 54(b) ......................................... ...................... 33

F.R. Civ. P. 65(d) .......... ........................... .'........... ............. 64n

Supreme Court Rule 23(c)(1) ...... ................................... 42n

Supreme Court Rule 40(1) (d )(2 ) ............................ ...... 42n

Other Authorities:

Bureau of the Census, General Social and Economic

Characteristics (1970), Tables 119-120, 125 ............ 54

Michigan House Journal (1970) ................. ...... ........... . 14n

3A Moore’s Federal Practice 1719.107[3] (2d ed. 1972).. 68n

Notes of the Advisory Committee, 1966 Amendments,

Rule 19 ............................... ....... ......... ..... ................. 67, 68n

Opinions of the Attorney General of Michigan ........... 77n

Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure

(1970) 73n

I n t h e

(Ecurt nf % Inttpfc Plaits

October T erm, 1973

No. 73-434

W illiam G. M illiken , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

R onald G. B radley, et al.

Respondents.

No. 73-435

A llen P ark P ublic S chools, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

R onald G. B radley, et al.

Respondents.

No. 73-436

T he Geosse P ointe P ublic S chool System , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

R onald G. B radley, et al.

Respondents.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Questions Presented

1. May the State of Michigan continue the intentional

confinement of black children to an expanding core of

2

state-imposed black schools within a line, in a way no less

effective than intentionally drawing a line around them,

merely because petitioners seek to interpose an existing

school district boundary as the latest line of containment?

2. Where further proceedings among all conceivably af

fected petitioner and amici school districts are poised be

low, at which all parties have a meaningful opportunity to

be heard prior to the entry of any injunctive order, should

this Court vacate the prior rulings of the lower courts, dis

miss this case, and hold that the three and one-half years of

prior adversary proceedings between plaintiffs and State

and Detroit defendants are for naught because suburban

school districts were not joined as parties at the outset

of this litigation?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves primarily the application of the

Equal Protection Clause of Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. In

addition- to the other constitutional and statutory provi

sions cited by petitioners, this case also involves the Thir

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and

42 U.S.C. §■§ 1981, 1983, 1988 and 2000d, as well as certain

other provisions of Michigan law set forth by Respondents

Board of Education of the City of Detroit, et al.

Counter-Statement of the Case

A. Nature of Review

The Reconstruction Amendments, particularly the Four

teenth, were made part of the United States Constitution

primarily in order to abolish the institution of slavery and

all its trappings so that freedmen and their descendants, as

3

individuals and as a class, could be made not only persons

and citizens in the eyes of the law and this Court (see Dred

Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1856)), but also

equal to the dominant white class, at least in all the public

affairs and public institutions of and within each of the

States of the Union. Slaughter House Cases, 83 U.S. (16

Wall) 36 (1873); Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303

(1880); Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880); Neal v.

Delaware, 103 U.S. 386 (1881); Civil Bights Cases, 109 U.S.

3 (1883).1 Nevertheless, with the express sanction of this

Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), enforced

segregation replaced slavery to perpetuate the second-class

public (as well as private) status and state-imposed badge

of inferiority of black people.2 In Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), 349 U.S. 294 (1955), the first

of many frontal assaults on public segregation in many

areas, this Court finally repudiated any type of official seg

regation in public schooling precisely because such segre

gation violates the fundamental purpose of the Fourteenth

Amendment as initially construed by this Court. See

Brown I, 347 U.S. at 490-491 and n.5.

1 “ [The Fourteenth Amendment] nullifies and makes void all

state legislation, and state action of every kind, . . . which denies

to any [citizen of the United States] the equal protection of the

laws.” 109 U.S. at 11. The Reconstruction Amendments had as

their “ common purpose” to secure “ to a race recently emancipated,

a race that through many generations have been held in slavery,

all the civil rights that the [white] race enjoy . . . ; and in regard

to the colored race, for whose protection the [Fourteenth] Amend

ment was primarily designed, that no discrimination shall be made

against them by law because of their color.” 100 U.S. at 308.

“ [Flying at the foundation of the [Reconstruction Amendments

was] the protection of the newly-made freeman and citizen from

the oppression of those who had formerly exercised unlimited

dominion over him.” 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) at 71.

2 Dissenting in Plessy, Mr. Justice Harlan prophetically noted

“ [i]n my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time,

prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal

in the Dred Scott Case.” 163 U.S. at 559.

4

Yet from Brown to this day black children in Detroit

have suffered from just such constitutionally offensive,

state-imposed school segregation. After extensive hearings

the record evidence showed, and the District Court found,

that from at least 1954 through the trial respondent black

children have been intentionally assigned by a variety of

de jure devices to virtually all-black (90% or more black)

schools. (J. 17a, et seq.)* Throughout this period the

pattern was and is unmistakable: State and Detroit school

authorities, operating in lockstep both with pervasive resi

dential segregation throughout the metropolitan area (it

self primarily the product of public and private discrimi

nation, including the widespread effects of de jure school

practices) and with discriminatory state policies, inten

tionally assigned the rapidly growing numbers of Detroit

black children to an expanding core of virtually all-black

schools separate from and immediately surrounded by a

reciprocal ring of virtually all-white schools nearby. The

ring of white schools in some places began within Detroit

proper and in other places at the school district line but

extended throughout the metropolitan area.

At the time of trial over 132,700 black children, 75% of

the total within Detroit, were thus de jure segregated in

this core of 133 virtually all-black schools covering almost

the entire Detroit School District and reaching in many

instances right up to the boundaries of the suburban school

districts; the surrounding suburban school districts served

pupil populations over 98% white (excluding the few his

torically black suburban enclaves, the percentage is well

over 99). (J. 23a-28a; J. 54a-55a; J. 77a-78a; J. 87a).

Thus, as concluded by the Court of Appeals in affirming

# A note explaining record citations follows the body of this

Brief.

5

the District Court’s finding of a massive and pervasive

constitutional violation (J. 118a-159a), “ even if the segre

gation practices were a bit more subtle than the compulsory

segregation statutes . . they were nonetheless effective.”

(J. 158a).

Insofar as practicable and feasible, therefore, the lower

courts concluded that such longstanding and massive viola

tion required the complete and effective disestablishment

of the present and expanding, state-imposed core of “black

schools,” now and hereafter, considering the alternatives

available and the practicalities of the local situation, pur

suant to the commands of Brown I and II; Green v. County

School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Swann v. Charlotte-

MecTclenburg Bd. of Ed., 402 TJ.S. 1 (1971); and Davis v.

Bd. of School Commr’s, 402 U.S. 33 (1971). (J. 42a, J.50a-

51a; J. 56a, J. 60a; J. 84a; J. 158a-159a, 162a, 176a-189a).

Based on the record evidence the District Court found that

a plan of actual desegregation limited to the Detroit School

District would only perpetuate the violation: the core of

schools racially identified by de jure acts as “black,”

immediately surrounded by a ring of virtually all-white

schools, would remain essentially intact. Any remedy

confined within the borders of the Detroit School Dis

trict would merely expand the state-imposed black core

the little remaining way right up to the borders of the

suburban districts. Such narrow relief would “lead directly

to a single segregated Detroit School District overwhelm

ingly black in all of its schools surrounded by a ring of

[suburban schools] overwhelmingly white. . . .” (J. 172a-

173a) due to the environment for segregation already

fostered in the area and the flight of many of the remaining

whites from the Detroit School District to the nearby all-

white suburban sanctuaries. (J. 192-28a; J. 54-55a, J. 87a-

88a; J. 157a-165a; J. 172a-173a).

6

The courts below, therefore, carefully assayed the practi

calities of the local situation, state law and practice, and

the proof to determine whether existing school district

boundaries are absolute barriers to more effective and

complete disestablishment of the state-imposed black core

surrounded by a reciprocal white ring. They were forced

to ask what justification existed for permitting school dis

trict lines to serve as merely the most recent state-created

and maintained racial barrier.

The lower courts ascertained that existing school dis

tricts are subordinate instrumentalities of the state

created to facilitate administration of the State’s sys

tem of public schooling; that the State has the ulti

mate responsibility for insuring that public education

is provided to all its children on constitutional terms

and that no school is kept for (or from) any person

on account of race; that the defendant State Superinten

dent and State Board have considerable affirmative power

over, and the power to withhold necessary aid from, local

school districts to insure their compliance with the com

mands of law; that the existing school district boundaries

are unrelated in many instances even to intermediate and

regional school district lines, and generally bear no rela

tionship to other municipal, county or special district gov

ernments ; that the existing school district boundaries have

been regularly crossed, modified or abrogated for educa

tional purposes and convenience, as well as for segregation;

that the State has acted directly to control local school

districts, including to maintain, validate and augment

school segregation; that existing state law provides de

tailed and time-tested methods for handling the adminis

trative problems associated with pupil transfers across

districts and modifying school district boundaries by an

nexation or consolidation; that any legitimate state interest

7

in delegating administration of public schooling to any

degree in any fashion to local units conld be promoted by

a variety of arrangements not requiring that existing school

district lines serve as an impenetrable barrier to desegre

gation across those lines; that for most social and economic

and governmental purposes, the metropolitan area repre

sents one inter-related community of interest for both

blacks and whites, except with respect to schools and hous

ing;3 and that the Detroit Public Schools are not a separate

3 We do not mean to suggest that blacks as a class have not been

subjected to all variety of other forms of public and private racial

discrimination and intentional segregation in the Detroit area. See,

e.g., Stamps and United States v. Detroit Edison, 365 P. Supp. 87

(E.D. Mich. 1973) (employment discrimination). Rather, we mean

to suggest that enforced separation of blaek citizens as a group

from whites is primarily evidenced by the racially dual system of

schools and housing. Thus, in this classic school segregation case,

even if public authorities could shift the burden of school desegrega

tion to black parents contrary to Green and Swann, the record

evidence proves that black parents have long been, still are, and for

the foreseeable future will remain effectively excluded from white

schools as long as the only means of gaining admission is purchas

ing or renting a home in the exclusively white residential areas.

(E.g., Ia 156 et seq.; Ila 19— Ha 81 P.X. 184; P.X. 2; P.X. 16A-D;

P.X. 48; P.X. 183A-G; P.X. 122; 1 Tr. 163; P.X. 25; P.X. 37;

P.X. 38; P.X. 56; P.X. 18A; P.X. 136A-C.) As found by the Dis

trict Court with respect to the entire metropolitan area, black

citizens are generally confined to separate and distinct areas within

Detroit and excluded from the suburbs, “ in the main [as] the result

of past and present practices and customs of racial discrimination,

both public and private, which have and do restrict the housing

opportunities of black people.” (J. 23a). Needless to say, the black

schools are not any more likely to witness an influx of white stu

dents as long as white parents (fleeing Detroit proper, immigrating

for the first time to the Detroit area, or already residing in the

suburbs) remain sentient and the dual pattern persists protected

by school district lines: the black core is the school system main

tained for blacks while favored suburban systems will remain se

curely white behind residential segregation, school district boundary

lines, and whatever new school facilities are needed to accommodate

these “whites only.” (Cf. J. 79a-80a, 87a-88a) Courts of Appeals

currently agree that such effectively exclusionary schooling is an

independent constitutional violation. See, e.g., Cisneros v. Corpus

Christi Ind. Sch. Dist., 467 F.2d 142, 149 (5th Cir. 1972), cert,

denied, 37 L.Ed2d 1041, 1044 (1973) ; Kelley v. Guinn, 456 F.2d

8

and isolated island of segregation bnt rather are inextri

cably part of the State System of public schooling.4 (J.

36a-38a; J. 50a; J. 79a-80a; J. 96a; 137a-140a; 151a; J.

165a-171a).

100 (9th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 37 L.Ed.2d 1041 (1973) ; Davis V.

School Dist. of City of Pontiac, 443 F.2d 573, 576 (6th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied, 402 U.S. 913 (1971) ; U.S. v. Bd. of Sch. Commis

sioners of Indianapolis, 474 F.2d 82 (7th Cir. 1973), cert, denied,

37 L.Ed.2d 1041 (1973); U.S. v. School District 151, 404 F.2d

1125 (7th Cir. 1968); Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ.,

311 F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970); cf. Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-21;

Brewer v. Norfolk. 397 F.2d 37, 41-42 (4th Cir. 1968) ; Sloan v.

Tenth School District, 433 F.2d 587, 588 (6th Cir. 1970). As the

“remedy” apparently proposed by petitioners for the massive viola

tion here, such a racially exclusive system of schooling is a mockery.

4 The courts below thus analyzed this case in accordance with

Fourteenth Amendment principles early established and, since

Brown, re-established by this Court:

The constitutional provision, therefore, must mean that no

agency of the State, or of the officers or agents by whom its

powers are exerted, shall deny to any person within its juris

diction the equal protection of the laws. Whoever, by virtue

of public position under a state government . . . , denies or

takes away the equal protection of the laws, violates the con

stitutional inhibition; and as he acts in the name and for the

State, and is clothed with the State’s power, his act is that of

the State. This must be so, or the constitutional prohibition

has no meaning. Then the State has clothed one of its agents

with power to annul or evade it.

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 346-47 (1880) ; Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1, 17-20 (1958). School districts in Michigan are not

separate and distinct sovereign entities, but rather are “auxiliaries

of the state,” subject to its “ absolute power.” Attorney General

v. Lowrey, 199 U.S. 233, 239-240 (1905), aff’g 131 Mich. 639

(1902). And the State of Michigan’s “absolute power” over its

school districts must be exercised in accord with the supreme com

mands of the Federal Constitution: “ [The Thirteenth and Four

teenth Amendments] were intended to be, what they really are,

limitations of the power of the States. . . .” Ex Parte Virginia,

100 U.S. at 345. Accord, Broughton v. Pensacola, 93 U.S. 266

(1876) ; Mount Pleasant v. Beckwith, 100 U.S. 514 (1879) ; Mobile

v. Watson, 116 U.S. 289 (1886) ; Comanche County v. Lewis, 133

U.S. 198 (1890) ; Shapleigh v. San Angelo, 167 U.S. 646 (1897) ;

Graham v. Folsom, 200 U.S. 248 (1906); Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 U.S. 339 (1960) ; Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964).

9

Viewing these practicalities of the local situation in the

context of the nature and extent of the violation and the

inadequacy of relief confined within the borders of the

Detroit School District, the lower courts determined that

the equitable power of federal courts to disestablish now

and hereafter the present and expanding state-imposed

core of black schools was not limited to the boundaries of

the Detroit School District—precisely because such freez

ing of existing boundaries would merely serve to perpetu

ate in full force the intentional assignment of black chil

dren to a separate core of “black schools,” identified as

such by de jure state action, immediately surrounded by a

ring of all-white schools nearby. With equity power to do

more, however, the lower courts (pursuant to the joint sug

gestions by State defendants and plaintiffs) exercised their

discretion to defer decision on any substantial modification

of existing school districts or school district lines to the

State. Pending such state determination, any desegregation

across school district lines was to be accomplished by the

method least intrusive on existing arrangements, by con

tracts and pupil transfers between the existing school dis

tricts pursuant to the provisions of state law. (J. 80a; J.

177a, J. 188a-189a).

The narrow issue of substance on review by this Court,

then, is whether petitioners’ argument that the school dis

trict lines may be interposed in such circumstances to per

petuate the walling-off of blacks in a state-imposed core of

overwhelmingly black schools separated from a ring of

overwhelmingly white schools only by that line is constitu

tionally acceptable: are existing school district boundary

lines, whose justification on this record is that they are and

have been there, really constitutionally immune? May

school district lines thereby serve to segregate black from

white children in a way that a school zone line (Swann), or

10

super highway (Davis), or newly created school district

line (Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972)), or other artifact of school administration (Green;

Raney v. J3d. of Ed., 391 U.S. 443 (1968); Monroe v. Bd.

of Commrs., 391 U.S. 450, (1968)), however untainted their

genesis, may not?5 In historic perspective then, if the peti

tioners are correct, all will understand that Brown’s reach

has exceeded our grasp: along the existing school district

line may Plessy be reconstructed sub silentio.6

5 Due to the State defendants’ default in failing to comply with

the District Court’s orders, no actual plan of desegregation extend

ing beyond the borders of the Detroit School District has ever been

submitted to or considered by the District Court. (J. 62a-64a). The

appeal to the court below was on an interlocutory basis. (J. 108a;

J. 112a: la 265-266). On remand, proceedings are already under

way among all conceivably interested parties in the District Court

in order to develop and consider such plans and to cure the poten

tial procedural error, ascribed to the District Court by the Court

of Appeals, in failing to give districts potentially affected by any

plan ordered the prior opportunity to be heard. (J. 176a-179a; la

287-302). Review by this Court at this basically interlocutory stage

of the proceedings, therefore, is premature for the reasons previ

ously stated in our Memorandum in Opposition to Petitions for

Writs of Certiorari. Review at this posture, however, does permit

consideration of the pure legal issue wholly free from jockeying

about walk-in schools and reasonable time and distance limitations

for transporting pupils to schools; for here the school district line

separates the black schools on the edge of the black core from many

adjacent, conveniently walk-in, all white schools. Compare Swann,

402 U.S. at 29-31, with Keyes v. School District No. 1, 37 L.Ed.2d

at 572-3, 581 (separate opinion of Powell, J.).

6 Petitioners, public servants serving predominantly white con

stituencies, argue to the contrary, that black plaintiffs premise

their case for relief beyond the Detroit School District on an as

sumption of inferiority of blacks and the per se unconstitutionality

of majority black schools rather than the enforced segregation of

black children as a class from whites. Such a suggestion from

public officials in 1974 is old wine in new bottles; it is no more

and no less than the racial sophistry adopted almost 80 years ago

by this Court in Plessy in rejecting black plaintiffs’ consistent

argument, from Reconstruction to this very day, that “the enforced

segregation of the races stamps the colored race with a badge of

inferiority” :

If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act,

11

B. The Proceedings Below

1. Preliminary Proceedings

Plaintiffs commenced this action over three years ago,

August 18, 1970, invoking the jurisdiction of the District

Court under 28 TJ.S.C. §§ 1331(a), 1343(3) and (4), and

asserting causes of action arising under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981,

1983, 1988, 2000d and the Thirteenth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution. Plaintiffs sought declara

tory (28 TJ.S.C. $§ 2201, 2202) and injunctive relief against

Michigan’s Governor, Attorney General, Superintendent of

Public Instruction and State Board of Fjducation, and the

Detroit Board of Education, its members and Superinten

dent of Schools,7 alleging de jure segregation of the Detroit

Public Schools resulting from historic public policies, prac

tices and action. Plaintiffs sought complete and lasting

relief from that segregation, which keeps well over 132,000

black children in a core of over 130 virtually all-black

schools segregated from white children in a ring of virtu

ally all-white schools.

but solely because the colored race chooses to put that con

struction on it. 163 U.S. 537, 551 (1896).

With respect to such ad hominem attacks by petitioners on black

plaintiffs’ goal of eradicating state-imposed segregation completely

and forever, nothing further need be said. However, as petitioners

make this same racial attack on the personal motives of the lower

court judges in ruling on this, case (see, e.g., Grosse Pointe Brief

43-45; Allen Park Brief 51; Allen Park Petition 13-14; State Peti

tion 13-14, 35), we feel compelled to set the record straight, point

by point. See infra, pp. 15, 23-25, 30-31. It is sufficient for our

purpose here that petitioners’ suggestion that the lower court

judges are racists at heart in seeking desegregation beyond the

geographic limits of the Detroit School District recalls precisely

the harsh realities of the Plessy rationale in blunting the Four

teenth .Amendment until discredited, finally, by the promise of

Brown.

7 The Detroit Federation of Teachers and a group representing

white homeowners within Detroit intervened as parties defendant

prior to trial on the merits.

12

The filing of the complaint was precipitated by the State

of Michigan’s then most recent, direct imposition of school

segregation on these black children. The State, “ exercising

what Michigan courts have held to be is ‘plenary power’

which includes power ‘to use a statutory scheme, to create,

alter, reorganize or even dissolve a school district, despite

any desire of the school district, its board, or the inhabits

thereof,’ ” (J. 27a) had acted with unusual dispatch follow

ing a Detroit Board adoption, its first ever, of even a small

scale, two-way high school desegregation attempt along

with a state-mandated decentralization program. In eon-

junction with a local recall of the Detroit Board members

who supported even this initial effort to breach the dual

structure by assigning white children to black schools, the

legislature passed Public Act 48 of 1970 (la 10-14) as a

direct response to obstruct such action forever.

Act 48 (1) reorganized the Detroit School District (here

after DSD), created racially discrete regional sub-districts

wholly within the DSD, and revalidated the external bound

aries of the DSD, all in the face of alternative proposals to

decentralize school administration in the metropolitan area

across the borders of the DSD to accomplish desegregation

(Compare la 10-14 and la 35 with Va 91-101 and la 26); (2)

unconstitutionally nullified the previous high school deseg

regation effort of the Detroit Board; and (3) interposed for

the DSD, and no other school district, unconstitutional pupil

assignment criteria of “ free choice” and “neighborhood”

which (as later found by the District Court) “had as their

purpose and effect the maintenance of segregation.”

(J. 27a-28a; see also 433 F.2d 897). On a racial basis the

State maintained inviolate the core of black schools and

singled out the DSD (and its mass of black citizens) for

separate treatment from all other (and overwhelmingly

white) school districts.8

8 In all these respects, the District Court found Act 48 to be one

of the examples where the “state and its agencies, in addition to

Plaintiffs prayed for a preliminary injunction to rein

state the partial plan of high school desegregation adopted

their general responsibility for and supervision of public education,

have acted directly to control and maintain the pattern of segrega

tion in the Detroit schools.” (J. 27a,). Petitioners’ arguments that

Act 48 either had no racial purpose (Grosse Pointe Brief 22) or

effect (State Brief 40-41) ignore the entire record evidence of

violation and the context in which this Act was so precipitously

adopted. In this respect, as so many others, petitioners seek to

have this Court review each finding of. fact separately and in com

plete isolation from each other fact, historical context, and the

careful deliberations of the District Judge over the whole record

evidence. Such “ fact” ploy is understandable but only clouds the

significant legal and constitutional issue which this Court must

decide. It also is contrary to this Court’s traditional reliance on

district court factual determinations, affirmed by courts of appeals,

in the context of the myriad local conditions presented by different

cases, particularly school segregation eases. See, e.g., Wright v.

Emporia, 407 U.S. at 466; Swann, 402 TT.S. at 28; Brown II, 349

U.S. at 299; United States v. Johnston, 268 IJ.S. 220, 227 (1925) ;

Amer. Const. Co. v. Jacksonville T. eft K. R. Co., 148 U.S. 372, 384

(1893) - Graver Mfg. Co. v. Linde Co., 336 U.S. 271, 275 (1948). It

is sufficient for our purposes here with respect to the motive

of Act 48 to note the following: Then Detroit Superintendent

Drachler’s uncontroverted testimony was that Act 48 was “an at

tempt then to turn the door back or the pages back.” (8/29/70

preliminary hearings Tr. 202; see also I lia 244-245). Then Board

President Darneau Stewart, subsequently recalled for his support

of the partial desegregation plan, stated with respect to Act 48,

“ I do regret that the legislature has found it necessary to intervene

in our carefully outlined plans and hopes . . .” (8/29/70 prelim

inary hearings Tr. 327-28).

Petitioners’ citation to the ultimate votes of black legislators

in favor of Act 48 (Grosse Pointe Brief 21-22) is only the most

recent example of the kind of misleading irrelevancy that peti

tioners have interjected from time to time to divert rather than

advance the inquiry in this case, akin to their implication that

plaintiffs must be ill with self-hate because we prefer constitu

tional schools to separate-but-equal schools. Here, petitioners seek

to obscure the fact that such approval was merely a final vote on

a general bill reflecting political acceptance of the legislative re

ality. Black legislators acceded to the already legislatively man

dated segregation in return for the hope of a modicum of the

same control over the “black schools” as whites maintained over

their white suburban school district enclaves. At earlier stages in

votes on particular parts of the bill, black legislators vociferously

opposed the Act whose purpose and effect were to roll back initial

efforts at desegregation, reimpose segregated pupil assignments,

by the Detroit Board but thwarted by Act 48, pending a

full hearing on the merits. After a preliminary hearing,

and ever after insure that white children would not again he as

signed to black schools. For example:

Rep. Vaughn: “First, the House today, and I think this is

perhaps the saddest day—April 9 will go down in history—

in Michigan history. It is the day the House of Representa

tives, at the State Capitol, Michigan, voted officially to nul

lify the Bill of Rights and the Constitution and violate the

basic laws of the United States Supreme Court. . . . And what

did the State House today say: We must segregate. Nullifica

tion. This is what southern senators do—plot on how to cir

cumvent a basic rule, a basic rule that would bring the schools

together.” House Journal No. 49, p. 1120 (April 9, 1970).

Rep. Mrs. Elliott: “ The passage of this bill is a step back

wards because of the crippling amendments that will continue

to perpetuate segregation.” House Journal No. 49, p. 1122

(April 9, 1970).

Rep. Mrs. Saunders, June 5, 1970, House Journal No. 88, p.

2160: “ I voted no on the Senate substitute for House bill

no. 3913 because I believe it can only have the result of fur

thering and intensifying segregation in education, a segrega

tion which has been contrary to the law of the land since

1954. Many of you sat smugly in Michigan while the southern

states protested the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education

landmark decision. You thought you were so much more vir

tuous in this basic humanitarian tenet of considering all men

as equal and realizing that separate is not, never was, and

never can be equal. . . . I am disappointed—I ’m deeply dis

appointed— I ’m ashamed of your action and response to racist

fears. You have helped to both divide and move our society

in a backward direction.” (Emphasis supplied).

Thus, the racial purpose underlying Act 48 is as obvious as any

of the Jim Crow laws. And its pervasive stigmatizing effects ex

tend beyond the borders of the DSD. For with respect to the

segregative pupil assignment criteria, the State intentionally created

what amounts to a racial classification between the DSD and

all other school districts (Cf. Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) ;

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969); Lee v. Nyquist, 318

F. Supp. 710 (W.D.N.Y.), aff’d per curiam, 402 U.S. 935 (1971)),

and thereby affixed the State’s badge of approval on the mainte

nance in the Detroit area of a separate core of black schools

surrounded by a ring of all-white schools. It should be no consola

tion to petitioners that Michigan’s first Jim Crow school law fol

lowed Reconstruction by 100 years. (See also discussion infra,

p. 52).

15

beginning August 27, 1970, the District Court denied all

preliminary relief and dismissed the Governor and Attor

ney General by ruling and order of September 3, 1970.

(Ia 59-63.) On Plaintiffs’ appeal the Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit affirmed the denial of preliminary relief

but held Act 48 unconstitutional insofar as it nullified the

initial steps taken by the Detroit Board to desegregate

high schools and interposed segregative pupil assignment

criteria for the DSD. In remanding for a hearing on the

merits the Court also directed that the Governor and Attor

ney General remain parties defendant. Bradley v. Milliken,

433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970).

On remand, the plaintiffs sought again to require the

immediate implementation of the Board’s high school plan

as a matter of interim relief to remedy some of the mischief

created by the enactment of the unconstitutional statute,

without determination of the more general issues raised

in the complaint. Instead, the District Court permitted the

Detroit Board of Education to propose alternative plans

and on December 3, 1970 approved one of them (Ia 88-97)

(a “ free-choice” approach which later proved upon imple

mentation to be not only wholly ineffective but also an

independent violation (J. 54a)); plaintiffs again appealed,

but the Court of Appeals remanded the matter “with in

structions that the case be set forthwith and heard on its

merits,” stating:

The issue in this case is not what might be a desirable

Detroit school plan, but whether or not there are con

stitutional violations in the school system as presently

operated, and if so, what relief is necessary to avoid

further impairment of constitutional rights. 438 F.2d

945, 946 (6th Cir. 1971) (emphasis supplied).

16

2. Hearings on Constitutional Violation

On April 6, 1971, as directed, the District Court began

the reception of proof on the subject of constitutional viola

tion. For 41 trial days, aided by hundreds of demonstrative

exhibits and thousands of pages of factual and expert testi

mony, the Court supervised a full and painstaking inquiry

into the forces and agencies which contributed to establish

ment of the by-now obvious pattern of racial segregation

in the Detroit public schools.9 This inquiry was more com

prehensive and probed more deeply into the causes of

existing school segregation than any of which plaintiffs’

counsel are aware.

The evidence revealed a long history, both before and

after Brown,10 of purposeful official action systematically

facilitating Detroit’s extensive pupil segregation. Virtually

all of the classic segregating techniques which have been

judicially identified, by this Court in Keyes11 and else

where, were employed or sanctioned by Detroit and State

school officials during the two decades from 1950 to 1970:

purposeful rescission of recent desegregation efforts; racial

gerrymandering of attendance zones, feeder patterns and

grade structures to maximize school segregation and pur

posefully incorporate precise residential patterns of segre

gation in schools; intact busing; in-school segregation;

racially selective placement of optional attendance areas

9 In 1960-61, of 251 Detroit regular (K-12) public schools, 171

had student enrollments 90% or more one race (71 black, 100

white) ; 61% of the system’s 126,278 black students were assigned

to the virtually all-black schools. In 1970-71 (the school year in

progress when the trial on the merits began), of 282 Detroit regular

public schools, 202 had student enrollments 90% or more one race

(69 white, 133 Hack) ; 74.9% of the 177,079 Hack students were

assigned to the virtually all-black schools. (Va 31-33).

10 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

11 Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 129, 37 L.Ed.2d

543 (1973).

17

or dual overlapping zones; discriminatory allocation of

faculty to mirror pupil racial composition of schools;12

and persistent and intentional segregative construction

(both of new schools and of enlargements to old ones)

and site location practices. (See, e.g., la 133-171; Ila 1-8;

IXa 82-111; Ila 111-159; Ila 160-312; I lia 1-18; I lia 18-53;

I lia 53-59; I lia 60-72; I lia 72-73; I lia 75-81; I lia 97-153;

I lia 158-206; Ilia 216-230; I lia 237-244; I lia 244-246;

Va 24-31; Va 31-34; Va 35-41; Ya 42; Va 43; Va 44-47;

Ya 48-68; Va 102-104; Ya 181-197; P.X. 63; P.X. 109 A -Q ;

12 The District Court found, however, that by 1970— and in large

measure at the behest of the defendant Detroit Federation of

Teachers and then Detroit Board’s Assistant Superintendent Mc-

Cutcheon in charge of personnel—the Detroit public schools were

engaged in a significant program designed to overcome past racial

faculty assignment patterns, and that because this program showed

promise of achieving its goals within Detroit, injunctive relief was

not required as to faculty allocation in the city schools. (J. 28a-

J. 32a). Such findings, however, with respect to faculty only dem

onstrate more clearly the high burden of proof imposed by the

District Court on plaintiffs at trial; for it was uncontroverted that

white Detroit areas were openly hostile to black faculty members

prior to 1960 and the Detroit Board accommodated this racial

hostility by refusing to assign black teachers into those predom

inantly white schools until the whites were willing (Tr. 45-49, Ilia

59; R. 2548-2549). As a result few black teachers and administra

tors were assigned to serve white student bodies and black teachers

and administrators were assigned generally to black schools. Staff

racial composition mirrored pupil racial composition, thereby fur

ther identifying schools as “black” or “white” during critical pe

riods of the record (e.g., P.X. 100 A -J ; P.X. 165 A-C, P.X. 154

A-C J.X. F F F F ; P.X. 166, P.X. 3 at pp. 73-79, Va 48-68). More

over, the availability of positions to whites in virtually all white

suburban schools coupled with an acute shortage in the supply of

teachers made recruitment and assignment of white teachers to

black schools difficult (e.g., R. 4471-4475; J. 31a); this further

exacerbated the racial pattern in the allocation of faculty. Although

this racial pattern in the allocation of faculty ameliorated some

what after 1965, the pattern still persisted at the time of trial so

that pupil racial composition of schools still could be determined

solely by reference to the faculty racial composition. As admitted

by then Deputy Superintendent Johnson, “ the pattern . . . is the

result of discrimination.” (Ilia, 223). (E.g., Ia 135-140; Va 44-45;

P.X. 100; P.X. 165, P.X. 154; Ila 276-278; D.X. FFF).

18

P.X. 16 A -D ; P.X. 136 A -C ; P.X. 137 A-G ; P.X. 147-149;

P.X. 153-153B; P.X. 154 A-C; J.X. F F F F ; P.X. 173.)

All of these de jure devices operated in lockstep with the

extensive residential segregation, itself the product of

public and private racial discrimination, to further ex

acerbate the school segregation and result in the inten

tional confinement of the growing numbers of Detroit black

children to an expanding core of virtually all-black schools

immediately surrounded by virtually all-white schools.

(See, e.g., la 156-164; XIa 9-19; XIa 19-22; Ila. 22, Ila 45-51;

Ila 23-28; XIa 28-45; Ila 51-60; Ila 60-64; Ila 64-69; Ila

69-72; Ila 176-273, 296-307; I lia 60-72; XXIa 73-74; I lia 64,

66-70; I lia 206; Ya 22; Va 24-30; Va 69-86, P.X. 183 A-G;

Ya 21-23; Ya 5-11; P.X. 38; P.X. 48A; P.X. 57; P.X. 60;

P.X. 16 A-D; P.X. 109 A -Q ; P.X. 184; Ya 89-90; P.X. 181;

P.X. 182; P.X. 189; Ex. P.M. 13-15; Ex. M. 5 (Exhibit B ) ;

Ex. M. 14).

Confronted by the evidence, the District Court concluded,

in its September 27, 1971 opinion, 338 F. Supp. 582 (17a-

39a), that although certain public and private non-school

forces of discrimination had also contributed to the cre

ation of Detroit’s highly segregated school system, per

vasive and purposeful discriminatory action at the state

level and by Detroit defendants, relating directly to the

public schools, was a significant causal factor.13 Therefore,

13 The District Court, like this Court in Swann and Keyes, did

consider the interaction between residential and school segregation.

The residential segregation throughout the metropolitan area was

shown by the evidence, and found by the District Court, to be,

“ in the main, the result of past and present practices and customs

of racial discrimination, both public and private . . and not the

result of the racially unrestricted choice of black citizens and eco

nomic factors (23a). The segregative actions of state and Detroit

school authorities (especially with respect to school construction)

and the environment for segregation fostered by the dual system

of schooling, i.e., the expanding black core immediately surrounded

by the white ring, was also found to interact with and to contribute

19

tile District Court held, the Fourteenth Amendment re

quired “ root and branch” elimination of the unlawful school

segregation and its effects.

3. Remedial Proceedings

a. The Practicalities of the Local Situation

The evidence at the violation hearing focused primarily

on the Detroit public schools, where over 132,000 black

children were assigned to a core of virtually all-black

schools, identified as black by official state action. How

ever, in exploring how these black schools were created

and maintained, and how their resulting state-imposed

racial identity could be effectively removed, the proof

of the pattern of state action affecting school segregation— 14

substantially to this residential segregation throughout the Detroit

area. This, in turn, further exacerbated school segregation. (J. 23a-

24a, 26a-28a, 35a; J. 77a-78a, 87a-88a, 93a-94a. See also J. 144a-

157a, 159a, 172a). Compare the similar relationship previously

noted by this Court in Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-22, and Keyes,

37 L.Ed.2d at 559-560, 565. As stated by the District Court “ on

the record there can be no other finding.” (J. 23a). Thus unlike

Bradley v. School Bd. of the City of Richmond, 462 F.2d 1058,

1066 (4th Cir. 1972), and contrary to petitioners’ assertions (e.g.,

Grosse Pointe Brief 38), the District Court did take evidence and

make findings, supported by overwhelming proof, as to the

racially discriminatory causes of residential segregation in the

metropolitan area and the important contribution to that condi

tion of the de jure actions of school authorities. (In Argument,

infra, pp. 43-49, we will analyze the factual and. legal implications

of these findings.)

14 As a dramatic example, consider the Higginbothom community

in Detroit and the adjacent Carver School District. The Higgin

bothom community had been built up as a black “pocket” by tem

porary World War II housing, designated for black occupancy, on

the outskirts of Detroit and extended beyond the city limits into

Oakland County and the old, almost all-black Carver School Dis

trict. The boundaries for the newly constructed black Higginbothom

school in Detroit were created and maintained to coincide with the

precise perimeters of the black “pocket” in Detroit, which perim

eters were also marked both by an actual cement wall built by the

white neighbors and the boundaries of the adjacent all white schools

20

just as did the acts themselves14—extended beyond the

geographical limits of Detroit.15 The evidence compelled

viewing the Detroit Public Schools as part of a State sys

tem of public education, not a detached island of un-

remediable segregation. * 16

imposed by school authorities to cordon off the area. To the im

mediate North of the Higginbothom school, the black “ pocket” ex

tending outside Detroit was contained within the small, all-black

Carver School District. That black district lacked high school

facilities. The state and Detroit school defendants accommodated

these black suburban high school pupils for years, from at least

1948 through 1960, by busing them past or away from several closer

white schools, across school district lines, to a virtually all-

black high school in the inner core of the city. These black stu

dents were not housed in suburban high schools but were bused

across school district lines, for the purpose of segregation, thereby

further marking the neighboring suburban schools as “white” and

the inner schools as “black.” (The Carver School District was

finally split in two and merged into the Ferndale and Oak Park

School Districts. Yet, at the elementary level, all the suburban stu

dents in this black “pocket” continued to attend two virtually

all-black suburban schools. The Court of Appeals in another action

upheld the HEW finding and withholding of federal funds with

respect to such vestige of state-imposed segregation, see School

Dist. of Ferndale v. HEW, No. 72-1512 (6th Cir., March 1,

1973). (J. 26a; J. 80a, 96a; J. 137a-139a, 152a.) (See also, e.g,

la 157, 162; I.R. 163; P.X. 78a; P.X. 19 p. 71; 11a 109-110; 11a

131; I lia 206; Ya 181-182; Ya 186; P.X. 184; Va 89-90.) That the

state defendants are ultimately responsible for this patent act of

segregation from their general supervisory powers is clear (e.g., J.

36a-38a). Their particular responsibility for this violation and ac

quiescence in it is equally clear: they have supervisory responsi

bility for regulation of all aspects of school busing, including

the routing buses. (J. 36a; M.C.L.A. 388.1010(c)).

16 This evidence of effective discrimination along or beyond the

DSD borders ran only against the State defendants— the chief

state school officer, the State Board of Education which is charged

with general supervision of public education, the chief state legal

officer and the State’s chief executive—and Detroit defendants and

not against any suburban school district, its conduct, or the estab

lishment of its boundaries, as specifically noted by the District

Court. (J. 60a). The evidence presented related primarily to (1)

the State’s policies and practices effecting segregation within and

of the Detroit public schools vis-a-vis its suburban neighbors with

respect to Act 48, school construction, merger of districts, pupil

21

The proof showed that in practical terms there are now,

and for years have been, two sets of schools in the Detroit

area: one virtually all-black, expanding core in the DSD,

surrounded by another virtually all-white ring beginning

in some areas at the border of the DSD but everywhere

extending throughout the suburban area beyond the geo

graphical limits of the DSD. By 1970 the black core in the

DSD contained some 132,700 black pupils in 133 schools

more than 90% black, made racially identifiable by per

vasive discriminatory actions and practices of state and

Detroit defendants. In stark contrast in the school dis

tricts in the metropolitan area surrounding16 16 the Detroit

public schools, between 1950 and 1969 over 400,000 new

pupil spaces were constructed in school districts now serv

ing less than 2% black student bodies (Exs. P. M. 14; P. M.

15). By 1970 these suburban areas17 assigned a student

assignment across school district boundaries for the purpose of

segregation, faculty allocation, and disparity of bonding authority

and transportation funding and (2) to actions by Detroit and

state defendants which not only contained black youngsters in

designated Detroit schools but which had the reciprocal effect of

further earmarking the surrounding ring of schools—in Detroit

and the suburbs—-as white. (J. 26a, 28a, 38a; -J. 77a-78a, 87a-88a,

93a-94a; J. 144a~157a). Contrary to the Petitioners’ assertions,

the evidence of state law and practice showed that school districts

in the Detroit area were not separate, identifiable, and distinct,

except with respect to race. (See, e.g., J. 23a-24a;J. 36a-38a; J.

50a; J. 77a-81a; J. 87a-88a; J. 151a-157a; 165a-173a).

16 Hamtramck (28.7% black) and Highland Park (85.1% black)

are surrounded by the Detroit School District.

17 There are also small, long-established concentrations of black

population outside Detroit which are located in Beorse, River

Rouge, Inkster, Westland, the old Carver School District (Perndale

and Oak Park), and Pontiac. As within the DSD, the black and

white pupils within these districts also remained substantially seg

regated in 1970-71. (E.g., P.X. 181, 182, 184; Ex. P. M. 12; Ya. 111-

115). Such a systematically segregated result is entirely consistent

with the history of de jure segregation throughout the State. Con

trary to Petitioners’ assertions that the State has enjoyed a long

“unitary” history, this case is not an isolated exception; at least the

22

population of 625,746 pupils, 620,272 (99.13%) of whom

were white, to virtually all-white schools. Within the con

text of the segregatory housing market and environment

for segregation fostered by the dual system of schooling,

this massive suburban school construction contributed to

the migration of whites from the city to, and the location

of whites immigrating to the Detroit area in, the suburbs.

In turn, this had a reciprocal effect on the racial composi

tion of the Detroit Public Schools which “has been sub

stantial” . (J. 78a). Throughout the metropolitan area,

faculties mirrored the racial composition of the student

bodies of schools, thereby further earmarking them as

“white” or “black” schools. For example, within Detroit,

41.8% of the teachers were black; in the suburban areas

above with less than 1% black pupils, only 0.4% of the

faculty were black. (Exs. P.M. 13; P.M. 18).

Finally, the evidence indicated that absent appropriate

judicial intervention, this unmistakable pattern of school

segregation would continue: In the environment for

segregation created by the long history of de jure school

segregation and the interrelated, pervasive and enforced

residential segregation, the state-imposed core of black

school population within the DSD would continue to expand

six other school districts in the State subjected to judicial scru

tiny have been found guilty of pervasive racial discrimination

with respect to the assignment of pupils or staff or both. Davis v.

Sch. Dist. of City of Pontiac, 309 F.Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich), ajf’d,

443 F.2d 573 ( 6th Cir. 1971) ; Oliver v. Kalamazoo, 346 F.Supp.

766 (W.D. Mich) aff’d, 418 F.2d 635 (6th Cir. 1971), on remand

------ F.Supp. ------ (K-98-71, Oct. 4, 1973), NAACP and Taylor

v. Lansing, -------F.Supp. ------- (W.D. Mich. 1973) ; School Dist. of

Ferndale v. HEW, No. 72-1512 (6th Cir., March 1, 1973) ;

Berry v. School Dist. of the City of Benton Harbor, (C.A.

No. 9, W.D. Mich. Feb. 3, 1970) (oral opinion) ; Higgins v. Grand

Bapids Bd. of Eel, ------ F.Supp. ------- (C.A. 6386)' (W.D. Mich.

1973). Thus the State’s express promises of a racially non-dis-

criminatory system of public schooling have long been denied to

the vast majority of blaek children throughout the State.

23

right up to the borders of the DSD and within a relatively

short time all of Detroit’s schools were likely to have nearly

all-black student bodies, all still surrounded by a ring of

virtually all-white schools.18 (J. 20a; J. 23a-24a; 54-55a).

b. The District Court’s Guidance by Settled Equitable

Principles and Its Order to Submit Plans.

It was in the light of this factual background, then, that

the District Court set about the difficult task of devising an

effective remedy for the extensive constitutional violation

and resulting massive school segregation which it had

found. Prom the beginning of its search for an appropriate

remedy to its final opinion on remedy, the District Court

was guided by the prior rulings of this Court and by set

tled equitable principles in “grappling with the flinty, in

tractable realities” of eliminating all vestiges of state-

imposed segregation. (J. 61a quoting Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 ITS 1, 6). In its first col

loquy with counsel concerning remedy, on October 5, 1971,

the district judge made clear that Davis19 and Broivn II20

established the contours of the future proceedings in the

case:

I want to make it plain I have no preconceived notions

about the solutions or remedies which will be required

18 Among the other practicalities of the situation confronted by

the District Court at this point, then, were the boundaries of the

DSD and the existence of other school districts, both local and

intermediate. The District Court’s determinations with respect

thereto are so much the primary subject of this Court’s review

that they will be set forth and analyzed in Argument, infra. (See

also Nature of Review, supra at 5-8).

19 Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs of Mobile, 402 US at 37

(1971).

20 Brown v. Board of Education, 349 US at 299 (1955).

24

here. Of course, the primary and basic and funda

mental responsibility is that of the school authorities.

As Chief Justice Burger said in the recent case of

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners:

— school authorities should make every effort to

achieve the greatest possible degree of actual de

segregation, taking into account the practicalities

of the situation.

Because these cases arise under different local condi

tions and involve a variety of local problems their

remedies likewise will require attention to the specific

case. It is for that reason that the Court has repeatedly

said, the Supreme Court, that each case must be judged

by itself in its own peculiar facts. (J. 42a).21

21 Petitioners’ use of the District Court’s remark at this same

colloquy with respect to “ social goals” and “ law as a lever” are

taken wholly out of context. (E.g., State Brief 77-78.) Where peti

tioners thereby imply that the District Court was motivated by

a “social goal” to accomplish “ racial balance” and “majority white

schools,” the District Court’s remarks were only a cautious state

ment of constitutional principles, defendants’ responsibility initially

to come forward with a plan promptly, and the practical prob

lems which have been experienced in implementing constitution

ally mandated desegregation in the face of white community

hostility. As this Court well knows, the historic course of righting

the constitutional -wrong of state-imposed school segregation has

not been easy and has been made more difficult by the recalcitrance

of school authorities and white communities over time. See

Swann, 402 U.S. at 13. Read in context then, the District

Court’s remarks about the “social” difficulties inherent in such

judicial intervention were an admonition to plaintiffs that the

Alexander command of “now” be understood in light of the prac

tical difficulties of devising and implementing a plan to provide

complete relief. The only conceivable error in such statement is

its suggestion that delay beyond the limits mandated by Alexander

and Carter might be required in view of the practicalities of the

local situation. Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396

U.S. 19 (1969) ; Carter v. West Feliciana Parish, School Bd., 396

U.S. 290 (1970).

25

In its last opinion on remedy, the District Court reiterated

the constitutional basis for its action.