Rule v International Association of Bridge, Structural, and Ornamental Ironworkers Brief of Plaintiffs Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 29, 1976

75 pages

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rule v International Association of Bridge, Structural, and Ornamental Ironworkers Brief of Plaintiffs Appellants, 1976. 76034361-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ca7bee21-8de1-46fb-9879-8b7865b51af8/rule-v-international-association-of-bridge-structural-and-ornamental-ironworkers-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

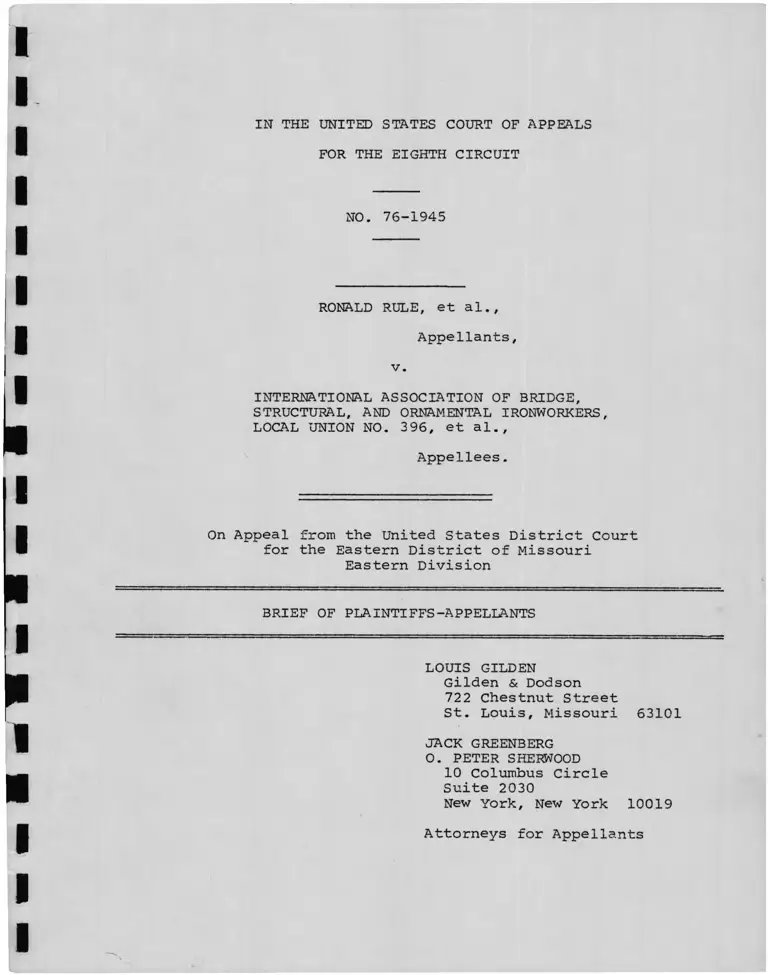

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-1945

RONALD RULE, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BRIDGE,

STRUCTURAL, AND ORNAMENTAL IRONWORKERS,

LOCAL UNION NO. 396, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Missouri

Eastern Division

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

LOUIS GILDEN

Gilden & Dodson

722 Chestnut Street

St. Louis, Missouri 63101

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................... ii

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW .......................... vi

NOTE ON FORM OF CITATIONS ................................ viii

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................... 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Introduction ..................................... 5

B. History of Racial Discrimination ................ 9

C. Employment in the Ironwork Trade ................ 17

D. The Joint Apprenticeship Program ................ 19

E. The Minority Training Program ................... 27

F. Effects of Local 396 Discriminatory

Practices on the Plaintiffs .................... 29

ARGUMENT ................................................ 36

I. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DECERTIFICATION

OF THE CLASS CONSTITUTES AN ABUSE OF

DISCRETION ....................................... 3 7

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN REFUSING

TO ADMIT PLAINTIFFS' EXHIBITS 26A ............... 39

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN REFUSING

TO CONSIDER CERTAIN EVIDENCE CONTAINED

IN THE GOVERNMENT'S CASE ........................ 41

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT'S FINDING OF NO UNLAWFUL

DISCRIMINATION AGAINST THE NAMED PLAINTIFFS

WAS BASED ON AN ERRONEOUS INTERPRETATION OF

THE LAW .......................................... 43

A. The Union unlawfully Discriminated

Against Ronald Rule in 1966 ................ 44

B. The Union Discriminated Against Ronald

Rule After 1966 ....................... 47

C. Willie West Is Entitled to a Remedy

from the Effects of Unlawful Discrim

ination Suffered in 1969 .................. 51

l

Page

D. Johnnie I. Brown Is Entitled to a

Remedy from the Effects of Discrim

ination Suffered in 1970 ................. 52

E. George Coe is Entitled to a Remedy

from the Effects of Unlawful Discrim

ination Suffered in 1970 ................. 54

F. Hiawatha Davis Is Entitled to a Remedy

from the Effects of Unlawful Discrim

ination Suffered in 1973 ................. 55

G. Plaintiff Lonnie R. Vanderson Is

Entitled to a Remedy from the Effects

of Unlawful Discrimination If He Was

Not Accepted Into JAC in 1975 ............ 57

H. Plaintiff Willie Nichols Is Entitled to

a Remedy from the Effects of Unlawful

Discrimination Suffered in February

1973 ....................................... 58

V. THE DISTRICT COURT'S REFUSAL TO CONSIDER

PLAINTIFF RULE'S CLAIM OF BREACH OF THE

MCHR CONCILIATION AGREEMENT CONSTITUTES

AN ABUSE OF DISCRETION........................... 59

CONCLUSION ............................................... 63

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ................................... 65

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) ...... 52,54

Baldwin-Montrose Chemical Co. v. Rothberg, 37 F.R.D.

354 (S.D. N.Y. 1964) 42

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 489 F.2d 896 (7th Cir.

1973) 53

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, Va.,

53 F.R.D. 28 (E.D. Va. 1971), rev'd 472 F.2d

318 (4th Cir. 1972), vacated 412 U.S. 92 (1974) .... 63

Bradshaw v. Associated Transportation, Inc.,

__ F. Supp. __, 8 EPD 59641 (M.D. N.C. 1974) 52

xi

Carey v. Greyhound Lines, Inc., 500 F.2a 1372

(5th Cir. 1974) ...................................... 50

Carr v. Conoco Plastics, Inc., 295 F. Supp. 1281

(N.D. Miss. 1969)..................................... 37

Causey v. Ford Motor Co., 516 F.2d 416 (5th Cir.

1975)................................................. 45

Cooper v. Allen, 467 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1972) ........... 44,54

Duncan v. Perez, 321 F. Supp. 181 (E.D. La. 1970)........ 43

Duplan Corp. v. Deering Milliken, Inc., 397 F. Supp.

1146 (D.S .C. 1974) ................................... .40

EEOC v. Mississippi Baptist Hospital, __ F. Supp. __,

11 EPD 510,822 (S.D. Miss. 1976)..................... 60

Florida v. Charley Toppino & Sons, Inc.,

514 F.2d 700 (5th Cir. 1975)......................... 43

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., __ U.S. __,

47 L. Ed .2d 444 (1976) ................................ 46,54

Fullerform Continuous Pipe Corp. v. American Pipe

& Construction Co., 44 F.R.D. 453 (D. Ariz.

1968) ................................................ 42

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ........... 44,45,48

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp., 498 F.2d 641

(5th Cir. 1974) ...................................... 47

Guerrino v. Ohio Casualty Insurance Co., 423 F.2d

419 (3d Cir. 1970) ................................... 42

Ikerd v. Lapworth, 435 F.2d 197 (7th Cir. 1970) ......... 42

In re Penn Central Commercial Paper Litigation,

61 F: R.D. 453 (S.D. N.Y. 1973) ...................... 40

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d

1364 (5th Cir. 1974) ................................. 49

Knuth v. Erie-Crawford Dairy Coop. Assn., 395 F.2d

420 (3d Cir. 1968) ................................... 37,38

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d

979 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ................................. 50

gage

iii

McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 292 (1973).... 4,44,53

McGuire v. Roebuck, 347 F. Supp. 1111 (E.D. Tex. 1972).... 43

Minyen v. American Home Assurance Co., 443 F.2d 788

(10th Cir. 1971)...................................... 41

NLRB v. Harvey, 349 F.2d 900 (4th Cir. 1965) ............ 40

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co.,

433 F. 2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970)......................... 44,48,49,50

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257

(4th Cir. 1976)........................................ 53,54

Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers Union of

New York and Vicinity, 384 F. Supp. 585 (S.D.

N.Y. 1974)............................................ 64

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974)...................................... 55

Rogers v. International paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340

(8th Cir. 1975) 45

Rowe v. General Motors, 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972) .... . 49

Sagers v. Yellow Freight Systems, Inc., 529 F.2d 721

(5th Cir. 1976)...................................... 38>

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147 (1969).. 43

Underwater Storage, Inc. v. United States Rubber Co.,

314 F. Supp. 546 (D.D.C. 1970) ...................... 40

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

517 F.2d 828 (5th Cir. 1975) ......................... 42

United States v. International Assn, of Bridge,

Structural and Ornamental Ironworkers, Civil

Action No. 71 C 559 (2) 4

United States v. Ironworkers, Local 10, __ F. Supp. __,

6 F.E.P. Cases 59 (W.D. Mo. 1973) ................... 36

United States v. Ironworkers, Local 86, 315 F. Supp.

1202 (W.D. Wash.), aff'd 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir.

1971), cert, denied 404 U.S. 984 (1971) ............. 36,49

United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d

354 (8th Cir. 1973) .................................. 44,45,46

Page

IV

Page

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36,

416 F. 2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969) ........................ 12,36,45,46

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp.,

89 F. Supp. 357 (D. Mass. 1950) ..................... 40

United States v. United States Steel Corp.,

520 F. 2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975)........................ 38

United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers, Local 46,

471 F.2d 408 (2d Cir. 1973) 47,64

Walker v. Ralston Purina Co., 409 F. Supp. 101

(M.D. Ga. 1974) ...................................... 63

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159 (5th Cir.

1976) ................................................ 48

Wright v. City of Montgomery, Ala., 406 F.2d 867

(5th Cir. 1969) ...................................... 43

Statutes and Rules

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Rule 23 .............................................. 2,37,38,

39,63

Rule 26 (d)............................................ 42

Rule 42 (a)............................................ 42

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964

42 U.S.C. § 1981 .................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.............................. 1,3,5,16,

42,49,54

Other Authorities

17 Am. Jur. 2d, Contracts §§ 305,306 .................... 60

EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

29 C.F.R. § 1607 .................................... 54

Public Law 94-559 ........................................ 63

Kaplan, Continuing Work of the Civil Committee; 1966

Amendments of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

(I), 1967, 81 Harv. L. Rev. 356 .................... 39

v

Page

5 Wigmore, Evidencet 3d Ed. 1940 § 1388 ................... 42

8 Wigmore, Evidence, § 2291 (McNaughton rev. 1961) 40

8 Wigmore, Evidence, § 2327 (McNaughton rev. 1961) 40

Wright and Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure:

Civil § 1785 .......................................... 38

Wright and Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure:

Civil § 1786 .......................................... 38

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Was the District Court's decision to decertify the

plaintiff class an abuse of discretion?

Points Relied Upon

KNUTH v. ERIE-CRAWFORD DAIRY COOP. ASSN., 395 F.2d 420

(3d Cir. 1968)

2. Did the District Court err in refusing to admit

plaintiffs' Exhibit 26A into evidence?

Points Relied Upon

DUPLAN CORP. v. DEERING MILLIKEN, INC., 397 F. Supp. 1146

(D.S.C. 1974)

IN RE PENN CENTRAL COMMERCIAL PAPER LITIGATION, 61 F.R.D.

453 (S.D. N.Y. 1973)

NLRB v. HARVEY, 349 F.2d 900 (4th Cir. 1965)

3. Did the District Court err in refusing to consider

evidence contained in the record of the Government's Case?

vi

Points Relied Upon

(a) Admissibility under Rules 26(d) and 42(a), F.R.Civ.P.

BALDWIN-MONTROSE CHEMICAL CO. v. ROTHBERG, 37 F.R.D. 354

(S.D. N.Y. 1964)

FULLERFORM CONTINUOUS PIPE CORP. v. AMERICAN PIPE &

CONSTRUCTION CO., 44 F.R.D. 453 (D. Ariz. 1968)

RULE 26(d), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

RULE 42 (a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

(b) Judicially Noticeable

DUNCAN v. PEREZ, 321 F. Supp. 181 (E.D. La. 1970)

SHUTTLESWORTH v. CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, 394 U.S. 147 (1969)

WRIGHT v. CITY OF MONTGOMERY, ALA., 406 F.2d 867 (5th Cir. 1969)

4. Was the District Court’s finding of no discrimination

against the named plaintiffs based on an erroneous view of the

law?

Points Relied Upon

GRIGGS V. -DUKE POWER CO., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)

PARHAM v. SOUTHWESTERN BELL TELEPHONE CO., 433 F.2d 421

(8th Cir. 1970)

UNITED STATES v. IRONWORKERS, LOCAL 86, 315 F. Supp. 1202

(W.D. Wash.), aff»d 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir. 1971), cert.

denied 404 U.S. 984 (1971)

UNITED STATES v. N. L. INDUSTRIES, INC., 479 F.2d 354

(8th Cir. 1973)

5. Was the District Court's refusal to consider plaintiffs'

claim of breach of the conciliation agreement error?

Points Relied Upon

EEOC v. MISSISSIPPI BAPTIST HOSPITAL, __ F. Supp. __, 11

EPD 5 10,822 (S.D. Miss. 1976)

vii

NOTE ON FORM OF CITATIONS

The following citations are frequently used in this

brief:

"PX - Exhibit offered by plaintiffs

at trial.

"DX - Exhibit offered by defendants

at trial.

"Tr. __" - Pages of the trial transcript.

"CA Tr. __" - Pages of the transcript of the

evidentiary hearing on plaintiffs'

motion for class action certi

fication.

"Ex .A Pages of exhibit A to plaintiffs'

renewed application for introduc

tion of certain evidence filed

May 1, 1975 and excluded from

evidence by the district court on

May 9, 1975.

"JAC Admiss. No. __" - Paragraph of Plaintiffs' Request

for Admissions addressed to the

Joint Apprenticeship Committee.

"Constitution ___" - Page or article and section of

npp ii

Constitution of the International

Assn, of Bridge, Structural and

Ornamental Ironworkers, AFL-CIO

attached as an exhibit to Local

396 Answers to Plaintiffs' Inter

rogatory No. 5(20) (a).

Paragraph number of the District

* Court's Findings of Fact.

"CL __" Paragraph number of the District

Court's Conclusions of Law.

viii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO-r 76-1945

RONALD RULE, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BRIDGE,

STRUCTURAL, AND ORNAMENTAL IRONWORKERS,

LOCAL UNION NO. 396, et-al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Missouri

Eastern Division

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal comes to this Court from a final order and

judgment on the merits rendered on October 6, 1976 in the

United States District, Eastern District of Missouri, Eastern

Division by the Honorable James H. Meredith. It presents several

procedural and substantive issues arising out of this action

challenging now familiar patterns of racial discrimination in

employment in the building construction trades in violation of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e

et seq. and 42 U.S.C. §1981.

Suit was commenced as a class action on March 14, 1973 by

plaintiff Ronald Rule alleging across-the-board patterns of un

lawful racial discrimination. (Orig. Complaint) Local 396,

International Association of Bridges, Structural and Ironworkers

(hereinafter Ironworkers or Union) was named as defendant.

>(Orig. Complaint) By leave of the court granted on November 27,

1973 plaintiff, amended his complaint to add the Ironworkers

Joint Apprenticeship Committee of St. Louis, Missouri (herein

after JAC) as a party defendant. On March 20, 1974 plaintiff

filed a second amended complaint adding eighteen (18) individuals

in their capacity as Trustees of the National Ironworkers and

Employer Training Program (hereinafter sometimes referred to as

Minority Training Program or MTP). The original complaint and

both amended complaints were duly answered denying all material

allegations. (Answers filed Apr. 30, 1973; Dec. 7, 1973; Mar. 13,

1974; August 22, 1974 and Sept. 12, 1974).

-1-

Plaintiff Rule's charge of unlawful racial discrimination

was filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(hereinafter EEOC) on June 30, 1966 thirteen (13) days after

he was refused an opportunity to work as an Ironworker or join

1 /its apprenticeship program. (PX-3, FF-3). EEOC did not

act on plaintiff's complaint. On or about January 15, 1973,

Plaintiff Rule received a notice of Right to Sue from EEOC and

so alleged on his complaint (PX-3).

On April 19, 1974 Judge Meredith held a hearing on class

action determination at which time plaintiffs presented six (6)

witnesses. (CA Tr.) The parties also entered into stipulation

indicating the number of blacks who were potential members of

the plaintiff class (Stip. filed April 24, 1974).

Plaintiff sought, pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2), ^.R. Civ. P.

to represent all black applicants for membership in Local 396,

its Minority Training Program or its Joint Apprenticeship Program

since July 2, 1965. Plaintiffs also sought to represent all pre

sent black journeymen, apprentices, trainees and service dues

receipt holders. (PI. Class Act. Memo, filed May 3, 1974).

2 /

On July 18, 1974, the district court certified a class

composed of:

i / He filed a similar charge with the Missouri Commission on

Human Rights (hereinafter MCHR). After Investigation the Iron

workers and MCHR, on December 28, 1971, entered into a concilia

tion agreement regarding plaintiffs complaint. In this action

plaintiff alleged the Ironworkers failure to comply with the terms

of that agreement. (Count III Pi. 2d. Amended Compl.)

2/ The district court did not specify under which subdivision

of Rule 23(b) the class was certified (Order of July 18, 1974).

-2-

Negro persons who have been members or

are members of said defendant Union and

JAC, and Negro persons who are applicants

or have been applicants for membership in

said defendant Union and JAC.

and ordered that notice be sent to each member of the plaintiff

class. That notice which was sent to the above defined class

members and black members of and applicants for the MTP, informed

the class members of the pendency of the suit and provided them

with an opportunity to "opt-out." They were further advised:

Any j udgment in the action whether or not

favorable to the members of the class will

include all members who do not request ex

clusion or who do not return the notice.

and will finally adjudicate the rights, if

any, or all class members who have not re

quested exclusion (emphasis added)

Of the 460 notices mailed 79 were returned undelivered.

306 class members chose not to return the notice. Of the 75

that were returned 50 class members requested exclusion, 17

requested inclusion and 8 were either unsigned or improperly

filled out. (Order of December 20, 1974). The district court

then reversed itself and refused to permit the case to proceed

as a class action. In the same order plaintiff was permitted

to contact and join as named plaintiffs those who requested in

clusion. (Order of December 20, 1974). Subsequently, Lonnie

Vanderson, George Coe, Willie Nichols, Johnnie L. Brown,

Hiawatha Davis, and Willie West were added as parties plaintiff

(Notice of Jan. 24, 1975).

During the pendency of this action, on November 9, 1973

the Ironworkers and JAC entered into a consent decree with the

United States resolving a §707, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-6, pattern and

-3-

practice suit alleging unlawful racial discrimination. At

trial plaintiffs unsuccessfully offered some of the proof de

veloped by the United States Justice Department in that action.

(Tr. 324-367 and PI. Ex. A).

At trial, held on three consecutive days, April 14-16,

1975, plaintiffs offered statistical and live proof of a pervasive

pattern of unlawful racial discrimination and its effects on the

named plaintiffs. Plaintiffs also presented proof of violation

of the conciliation agreement and the consent decree. Finally

plaintiffs offered unrebutted proof of monetary loss and plain

tiffs attorneys fee entitlement as of that time. After trial

the parties presented post-trial briefs. Plaintiffs urged that

they were entitled to relief not only on the basis of the statis

tical evidence presented but also on proper application of the

standards set by the Supreme Court in McDonnell-Douglas v. Green,

411 U.S. 292 (1973).

Post-trial briefing was completed on March 26, 1976. On

October 6, 1976 the district court rendered its decision dismiss-

ing plaintiffs complaint. The court found "no evidence" that

plaintiffs had been discriminated against, upheld the defendant's

reintroduction of unvalidated tests for the apprenticeship pro

gram, found the manner of referral of apprentices and minoritv

trainees to be non-discriminatory, refused to consider plaintiff

Rule's claim of breach of the MCHR conciliation agreement, refused

to act on clear proof of violations of the consent decree and

dismissed the action. (FF, CL)

Notice of appeal was filed on October 29, 1976.

3 / That action captioned United States v. International Assn.

of Bridge, Structural and Ornamental Ironworkers, Civil Action

No. 71 C 559(2) was pending before Judge Regan.

3 /

-4-

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Introduction

In order to better understand the Union as it impacts

on the employment opportunities of blacks and other minorities,

a short description of its institutions and their functions is

useful. A more detailed description appears in subsequent

subsections of the Statement of Facts.

1. The Union and Its Collective Bargaining Agreements

Local 396 is a labor organization within the meaning of

42 U.S.C. §2000e-(d). It is the St. Louis, Missouri affiliate

and subject to the constitution of the International Association

± Jof Bridge, Structural and Ornamental Iron Workers, AFL-CIO

(hereinafter International (see Ans. PI. Interrog. No. 5(20) (a)

at Art. IX, Sec. 4)) and is an affiliate of the Building and

Construction Trades Council of St. Louis, AFL-CIO (e.g. see

)

3/19/70, 6/18/70, 3/5/70, Minutes of Executive Committee in

PX-24). Through its collective bargaining agreements with the

Association of General Contractors of St. Louis, Concrete

Contractors Association, Site Improvement Association, Erectors

I

and Riggers Association and 92 independent building contractors-

(FF 22 and Ans. PI. Interrog. No. 10), the Union exercises vir

tually exclusive control of employment in the building and

construction ironwork trade in the St. Louis, Missouri

4 / The International is not a party to this action.

5 / Neither the contractors nor the contractor association are

parties to this action.

-5-

area. It also effectively controls training opportunities

within the trade. (JAC Ans. to Govt. Interrog. No. 14).

Under the terms of collective bargaining agreements, con

tractors are required to look first to the Union for workmen

(e.g., see PX-52 at Art. I, Sect. 1.03). Only if the Union

fails to provide workers may a contractor seek employees else

where (e.g., see PX-51 at Art. 1, Sect. 1.03). Any employee

who is not a member of the Union or who does not possess a

"permit” is subject to discharge upon demand by the Union

(e.g., see PX-51 at Art. 4).

Today there are four categories of ironworkers permitted

to work within the territorial jurisdiction of the Union. They

are journeymen, permitmen, apprentices, and trainees. A worker's

classification has a substantial effect on his opportunity to

find employment and his wage rate.

2. The Journeyman Ironworker >

Journeymen are fulfledged Union members. They alone

select Union officers and by their vote, determine Union policy,

including the ratification or rejection of collective bargaining

agreements. They receive the highest ironworker wage rate (here-

6 /

6 / Prior to August 1972, Local 396 exercised exclusive control

of all employment of employees in the iron work trade in the city

and county of St. Louis (see PX-51 and PX-52 at Axt. 2, Sect. 2.02).

It also asserted jurisdiction over construction work in several

outlying counties on the Missouri side of the Mississippi River

(See Id_. at Art. 2, Sec. 2.03). In August 1972 Local 396's terri

torial jurisdiction was expanded to include exclusive control over

the following Missouri counties: St. Charles, Jefferson, Franklin,

Lincoln and Warren. (See DX-E at Art. 2, Sect. 2.02). As of the

time of trial two-thirds of the Union membership lived in the

Metropolitan St. Louis Area. (Tr. 544).

-6-

inafter referred to as journeyman's wages) and have an un

restricted right to solicit work. By virtue of a collectively

bargained provision of the Union's contracts they are always

selected as job foremen and superintendents (e.g. see PX-51 at

pp. 20-21), and, in that capacity, exercise the traditional

management prerogatives to hire, fire, and assign other iron

workers (e.g♦ see PX-51 at p. 34 and Quick Deposition at

pp. 24-25).

3. The Permitman

Permitmen are not Union members, but they earn journeyman's

wages (Tr. 578, 678). The appellation "permitman" derives from

the fact that they hold service dues receipts or "permits" which

entitle them to work in the trade (Tr. 451-452).

of permits is controlled by the Union's Examining Board. See

P • 9, infra. Permitmen are not permitted to solicit work

but, at least until 1972, this rule was difficult to enforce

(Tr. 568-569).

4. The Apprentice

Apprentices are unskilled men who have been formally in

dentured into JAC (Constitution at p. 82). JAC is the tradi

tional Ironworker training program and is funded by building

contractor contributions (FF No. 36). Apprentice are Union mem

bers but have no voice in Union affairs and are otherwise subject

7 / In 1975 the journeyman wage rate was $9,275 per hour.

IDX-E at p. 11).

7 /

-7-

to a variety of restrictions. (Constitution at pp. 81-84).

Apprentices start at 60% of the journeyman's wage and receive

infra. While nominally prohibited from soliciting work, appren

tices do solicit with the knowledge and approval of Union

officials. (See n. 14, infra.)

5. The Trainee

Trainees are minority (mostly black) ironworkers who are

enrolled in the MTP (FF No. 46 ). The MTP has been in exis

tence since 1970 and is designed to provide training opportunities

for minorities and hard core unemployed whites who are over the

any collective bargaining agreement until 1973 (FF No. 45) and

are not Union members (Tr. 473. Myers Deposition at p. 21).

The MTP is funded by the United States Department of Health,

Education and Welfare. Some of the black trainees were skilled

in the trade prior to joining the program (Tr. 471 ). Like

apprentices, trainees receive a fraction of the journeyman wage.

See pp.27-28,infra. They are not permitted to solicit work but

had that right for a three-year period between November, 1973 and

November, 1976. (See Consent Decree).

8 / These increases are awarded automatically provided the

apprentices has attended classes regularly (Adam Deposition at

pp. 45-46). Performance on the job or in class is not a factor

Id. p. 61, 46).

9 / The apprenticeship program is essentially limited to persons

under age 30 (FF No. 38 ).

fractional increases at six month intervals 8 / See p. 28

(FF No. 43) Trainees were not covered by

-8-

6. The Examining Board

The Union's Examining Board is the body comprised of

elected union officials that is charged with responsibility for

10/determining individual eligibility for union membership

(See Constitution at p. 57). It also determines individual

eligibility for permits (Constitution at p. 97), and has the

authority to revoke permits (Tr. 213).

B* History, of., Raci al P.1 ,sce.imiriaji.iQii

Prior to 1964, the membership of Local 396 was all-white

12 /

(Tr. 680) . A person seeking membership in the Union was

required to be 18 years of age or older, complete the Union's

two-year apprenticeship program or work on service dues receipts

within the territorial jurisdiction of Local 396 for six months,

pass a simple demonstration test of skill in the trade and pay

an initiation fee (Tr. 624, 657, Ex. A at pp. 40-41). Since

skill in the trade is learned on the job (Ex. A at p. 45) and

10 / The Examining Board issues seven kinds of journeyman cards.

They are rodman, structural, rigging, fencing, welding, ornamental

and general (Ex. A at p . 52). In some ironwork locals, but not

Local 396, the type of card held defines the type of work a man

is permitted to perform (Tr. 447). In such locals only the holders

of general journeyman cards are permitted to work in all areas of

skill. The applicant determines the type of card he wants. The

Examining Board then administers an examination which tests his

skill in that particular area of the trade (Ex. A at pp. 17-18) .

Applicants for a general journeyman's card are tested in all areas

of skill.

In fact, the first black was not admitted to membership until

1967 (Local 396 Ans. to PI. Interrogs. No. 2 and Tr. 688).

12/ Qualification for membership is determined by the Examining

Board, (Constitution at p. 57). The membership of the Examing Board

as well as all otner elective and appointive positions have axways

been white (PI. Interrog. 21 and Ex. A at p. 2).

-9-

13/

■at least one area of skill was easy to learn, gaining

Union membership was a simple matter for anyone who was able to

work and train for six months.

There were certain distinct advantages to having a

journeyman's card. Journeymen, and no others, were entitled

to solicit work directly (Tr. 782, 453) and were the first to

be referred for work (Tr. 682). Apparently these rules were

14/

often ignored, but the Union retained the power to

enforce them.

A substantial number of ironworkers chose not to become

journeymen. Instead, they chose to work on service

13 / One can gain skill as a rodman in just two to six months

(Tr. 193 & Ex. A at p. 29).

14 / Charles Adam, coordinator of JAC, testified at a deposition

taken by the Government and described how the system worked in

the case of apprentices:

Q. (by Mr. Zaragoza) Going back to the work

procedure for apprentices, can apprentices,

to your knowledge, solicit their own work?

There's a rule that says an apprentice cannot solicit

his own work, but its not adhered to to the point

that says if a job is offered to this apprentice

and its okayed by the Business Agent, if he's there

at the time, or if I'm there at the time, or if they

call me on the phone and says, Hey, Chuck, I'm

getting laid off tonight, but the contractor next

to us, or the subcontractor on the job can use me,

can I go to work for him, sure, in other words, he

can call somebody and ask them, but all he has to

do is let the — Business Agent, and myself, and the

people involved in the work everyday, let them

know whats going on" (at pp. 22-23).

-10-

dues receipts as "permitmen." (Tr. 650) . An applicant for

a permit was required to appear before the Union's Examining

Board, obtain its approval, and pay an established fee

(Constitution at p. 97, Ex. A at pp. 34-35). Permitmen earn

the same wages as journeyman ironworkers (Tr. 578, 678,

Deposition of J. J. Hunt, Jr. at pp. 59-60). High School and

16/

college students, often the relatives of ironworkers, found

summer employment in the trade as permitmen (Tr. 193, 605-06).

Of course, this was an attractive avenue for the unskilled but

privileged to learn the trade on the job (Tr. 193, 394, 605-06).

This was also the means by which one could obtain the requisite

six months of work in the trade within the territorial iurisdic-

17/

tion of Local 396 (Tr. 651) .

15/

18 /

The Union also ran an apprenticeship program (Tr. 508-09)

It was a two-year program (Tr. 508-09). Applicants were not

15 / Meetings of the Examining Board to screen applicants for

permits were not regularly scheduled. Sometimes an applicant

would be screened immediately (Ex. A-34). Less fortunate applit

cants were required to wait until the Board chose to consider

applications (Ex. A-35).

16_/ See Quick Deposition at pp. 23-24, Tr. 193, 605-06 and

Ex. A-9. Mr. Quick, a contractor, testified that all summer

students were the relatives of union members.

17 / At least 172 of the approximately 570 persons admitted to

membership since 1961 had gained their skill in the trade as

permitmen (see Ans. to Govt. Interrog. No. 6). Only one,

Henry Joiner, is black, and he was permitted to take the journey

man's examination only after efforts to dissuade him failed.

(See Tr. 196-97) .

18 / This program too was largely the preserve of the friends

and relatives of union members (Ex. A at p. 28). At least

until 1973, the apprenticeship continued to be a major avenue

of entry into the trade for the friends and relatives of iron

workers (JAC Admiss. No. 43 and Ex. A at p. 27).

-11-

required to meet educational requirements or take aptitude tests

(Tr. 511-12, JAC Admiss. No. 30). Apprentices earned less than

journeymen and permitmen but gained exposure to all areas of the

trade (JAC Standards at p . 10). Like all other applicants for

journeyman union membership, graduate apprenticeshwere required

to appear before the Examining Board and be tested. Typically,

they received general journeyman cards.

By 1964, the federal government and St. Louis area civil

rights organizations began to pressure the Union 19/ and contrac

tors for an end to the exclusion of blacks from the trade.

(Tr. 29, 684, 688, 21-22 and L. Strauss Deposition at p. 30-31).

Correspondingly, the tide of black applicants for entry into the

trade began to rise. (E.g. see Tr. 14, 26, 382). At the insis

tence of a contractor who had a contract to build a federally

subsized low income housing project, the Union sought out two

blacks who worked in an ironworker shop local and provided them

with permits (See L. Strauss Deposition at pp. 29-33 and Tr. 688,

682-83). Of course, the two blacks did not know the ironworkers

who hire (Tr. 682-83) and could not solicit work (Tr. 682). As a

consequence, they found little work (Tr.683). But when contractors

needed blacks in order to comply with the requirements federally

subsidized construction contracts, they found themselves being

shuttled from job site to job site.

At the same time, the Union began to raise formal barriers

to work in the trade. In 1964 possession of a high school diploma

.19/ The struggle to open the doors to the construction trades

in St. Louis to minorities and the trade unions intractable

resistence has come to the attention of this Court previously.

See United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d 123

(8th Cir. 1969) .

-12-

or a G.E.D. was imposed as a requirement for entry into the20/

apprenticeship program (Tr. 511). In 1965 a battery of

aptitude tests were introduced to aid in the selection of

apprentices (JAC Admiss. No. 30). In 1967 the Union introduced

a written test in addition to the demonstration test previously

administered to all applicants for journeyman cards. (Tr. 657).

Predictably these rules had the effect of excluding a

21 /

disproportionate number of black applicants. In early 1975,

plaintiffs examined all of the applications for JAC found in the

Union's files and compiled statistics which disclose discriminatory

impact of the JAC eligibility and selection procedure. (See PI.

Req. for Admission filed 3/13/75). Of the 1180 racially identi

fiable applications found, 202 (17%) had been filed by blacks.

Two hundred ninety of the 978 whites (30% succeeded in gaining

admission. Just 22 of the 202 blacks (11%) were similarly success

ful. (See Exhibit I of PI. Req. for Admission filed 3/13/75.)

The Union's Answers to Plaintiffs' First Interrogatories also

disclose the slow progress of blacks in achieving union membership.

9 n___/ But this requirement was not consistently applied to whites.

At least one white, Edward Koeller who entered the apprenticeship

program in 1968, had less than 4 years of high school (See Ans.

to Govt. Interrog. No. 6 at p. 35).

21___/ July 1969, Joseph Hunt, Sr. reported on the experience of

the 38 blacks who had applied for admission to the apprenticeship

program since 1964 (PX-26(b)). Only two had successfully hurdled

the barriers mounted by the Union and gained admission to the pro

gram (See Hunt's letter to Hardesty located in PX-26(b)).

-22___/ These figures can be misleading. They include both journey

man members and apprentice members. The dramatic increase from

two (2) blacks in 1968 to eleven (11) in 1969 is due to the indenture

of seven (7) blacks into the apprenticeship program in 1969

(JAC Admiss. No. 39). As late as 1971 there were only five black

journeyman ironworkers (Ex. A. at pp. 4-5).

-13-

Year Whites Blacks

23/

% Black

1965 1378 No record available 0

1966 1447 No record available 0

1967 1487 1 0.06

1968 1610 2 0.12

1969 1632 11 0.67

1970 1700 18 1.05

1971 1665 19 1.13

1972 1615 23 1.40

1973 1601 23 1.42

In 1970, Local 396 established a minority training program

which was purportedly designed to afford blacks, other minorities,

and hard core unemployed whites an opportunity to work in the

trade and earn union membership (Tr. 403, Ex. A at pp. 44-45).

If anything, this program served to further perpetuate the exclu

sion of blacks (see pp.27-29,infra). At the same time, the Union

embarked on a program to reduce and ultimately eliminate the

availability of permits (Tr. 213). Black permit holders were

advised to enter the MTP and take a cut in pay (see p.28-29, infra)

if they wished to continue to be employed in the trade. Several

did (Tr. 471) but the Union was not content to have them suffer

some income loss. It insisted that trainees start at a lower wage

rate than apprentices (see p. 28 , infra) and that those trainees

who had prior experience in the trade start at a lower rate of pay

than the contractors were willing to pay I (Quick Deposition at

p. 45-47, Tr. 498-499).

23/ The first black was admitted to membership 1967

(Tr. 680, 688).

-14-

By 1971, the United States Department of Justice sued in"

3-H effort to force the Union to eliminate its unlawful practices,

but the Union's efforts to prevent the entry of blacks into the

trade continued unabated. Its next step was bold, and its effects

devastating to blacks: In 1972 the union went on strike and forced

area contractors to incorporate a grandfather clause in the new

collective bargaining agreement (Ex. A at p . 63 and DX-E at pp.

40-41). This clause, called a ’’Letter Agreement," established a

new classification system which gave first preference for job

openings to "Qualified Journeymen." Qualified Journeymen were

Union members who had worked a minimum of 6000 hours in the trade

within the territorial jurisdiction of Local 396 prior to the

24 /

effective date of the contract (DX-E at p. 41). Its effect

was to limit the first choice of jobs to persons who had been

25/

working in the trade for over four years (Tr. 545-46, Ex. A

at p. 64). Of course, few blacks had succeeded in achieving the

requisite 6000 hours of work in the trade as of November 29, 1972

(DX-E at p. 39). To further ensure that those with less than

6000 hours work in the trade had little opportunity for work,

the Letter Agreement prohibited such persons from soliciting

work (Deposition of W. H. Johnson at pg. 89) and required that

they be laid off before those with more than 6000 house (DX-E

at p. 41). In addition, the new contract for the first time

established a reporting mechanism that permitted the union to

effectively enforce its new rights (see DX-E at Sect. 7.20).

2 4 / JAC and MTP graduates were also defined as "Qualified

Journeymen." (DX-E at p. 41).

25/ JAC and MTP graduates would normally qualify in three years

since they are both three-year programs. But they pay the price

of working at reduced rates of pay during those three years.

-15-

On November 9, 1973, four months before it was scheduled

to lose authority to enforce Title VII in the private sector,

the United States Department of Justice entered into a consent

decree which altered some of the unlawful union practices for a

2

three-year period. Under the terms of the consent decree, the

union was enjoined from administering unvalidated tests, was

prohibited from applying the 6000 hour provision to blacks and

was required to meet established goals for the admission and

retention of blacks into JAC and the MTP (Consent Decree at 118) .

The consent decree made no provision for back pay. The Union

has failed to abide by the terms of the consent decree and the

28 /

Government has not sought enforcement.

26/ See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6.

2^/ However, it was permitted to use the results of tests admin-

stered by the Missouri State Employment Service (Consent Decree

at If8) . See n. 43 , infra.

2^/ The EEOC has been responsible for monitoring and enforcement

since March of 1974.

-16-

C. Employment In the Ironwork Trade

Today as in the past, employment in the ironwork trade

is obtained primarily by word-of-mouth contact among ironworkers

(Tr. 635). Contractors hire journeyman ironworkers as foremen

29/

and superintendents (Tr. 202) and they in turn develop and

maintain lists of ironworkers who are the first to be called

when there is work. (see Quick Deposition at pp. 12-13).

Whether or not called by a superintendent or foreman, ironworkers

are able to find work through an informal but highly developed

information network within the trade (Quick Deposition at p. 12).

As word of a new project gets around the trade, ironworkers who

have a right to solicit are able to call and get work (Quick

Deposition at p . 12). Only when a contractor is unable to find

an adequate number of workers does he resort to the union for

referrals. Thus, ironworkers having the right to solicit have

a decided advantage over those who do not. Blacks generally are

outside information networks and therefore have less of an oppor

tunity to find work (Quick Deposition at p. 17). Since they also

are not journeymen ironworkers, they have little recourse but to

30 /sit in the union hall and wait for a referral (see Tr. 682-83,

134) .

Blacks who are in the MTP are at a triple disadvantage.

25/ The collective bargaining agreements require contractors to

assign journeyman ironworkers as foremen. (see PX-51 at p. 20).

30_/ Blacks who have achieved journeyman status obtain most of

their work through solicitation (Tr. 219).

-17-

They are not permitted to solicit and are outside the infor-

32 /

mation network (Quick Deposition at p. 17). The third dis

advantage derives from the separate structure of JAC and the

MTP. JAC is the traditional and largely white Ironworker appren

ticeship program. The MTP is almost exclusively black (Tr. 429-30).

Foremen and Superintendents can and do contact the coordinators

of both programs directly (Tr. 535) If they call the

union hall for an apprentice, the union obliges by referring an

apprentice (Hunt, Jr. Deposition at p. 62-63). If they seek

referral of a minority, the union again obliges and refers a

33/

trainee (Hunt, Jr. Deposition at p. 63). Thus, the separate

structure of the two training programs provides a ready mechanism

for contractors to discriminate.

The effects of the dual training program structure on the

employment opportunities of blacks are substantial. In 1975,

34/

black trainees worked an average of 575.68 hours (Appendix A

21/

31/ For the three years that the Consent Decree was in effect

blacks, whether in the MTP, JAC or on permit, had the right to

solicit (Consent Decree 27, TR. 535-36).

32/ While blacks generally are outside the information network,

those enrolled in JAC have some access to the grapevine of infor

mation through their contact with white apprentices who are often

the relatives of journeyman ironworkers (Ex. A at pp. 27-28).

33/ Further, if a contractor calls for referral of a journeyman

and’none is available for referral, the contractor is advised of

his option to select an apprentice or trainee for referral (Hunt,

Jr. Deposition at p. 63).

34/ Trainees entering the MTP after September 1974 averaged less

than 100 hours of work in 1975 and are excluded from this average.

(Appendix A to Plaintiffs' Post-Trial Brief).

-18-

to Plaintiffs' Post-trial Brief). In that same year, black

apprentices worked an average of 741.93 hours. (Appendix A

to Plaintiffs' Post-Trial Brief). A comparison of the two

reveals that black apprentices were employed on an average of

35/

1.289 times as many hours as trainees.

D. The Joint Apprenticeship Program

JAC is administered by a committee comprised of five con

tractor and five Union members (JAC Admiss. No. 2). It controls

and administers the apprenticeship program in conformity with

published standards (JAC Admiss. Nos. 4 and 12), determines the

size of each apprenticeship class (Tr. 618-619), interviews,

rates and selects apprentices (see JAC Admissions). Since

February, 1970, the day-to-day handling of the program has been

handled by a full-time coordinator who is a member of the Union

(JAC Admiss. No. 5). The current apprenticeship program is a

three-year program of on-the-job training accomplished by a

minimum of 144 hours of related classroom and shop work per year

(JAC Admiss. No. 7).

35/ A substantial number of the white apprentices are the sons

of ironworkers. See n. 18, supra. In making the hours comparison

it is assumed that the higher average number of hours of work that

white apprentices enjoy is attributable to the effects of nepotism

within the trade. This factor is eliminated by comparing trainees

with black apprentices. White apprentices average 811.40 hours of

work. Apprentices overall averages 1.401 times as many hours of

work as trainees. (Appendix A to Plaintiffs' Post-Trial Brief).

-19-

1. JAC Admission Standards

Local 396 has conducted an apprenticeship program in one

36 /

form or another for decades. Published qualification stan

dards for admission to the apprenticeship program were formulated

in 1964.

The following describes the selection process as it

existed prior to the entry of the Consent Decree. Since

then JAC has revised the interview questions somewhat and has

altered slightly the weight given each of the factors that go to

make up the final rating scores on which applicants are selected.

(Compare JAC Admissions, Attachment 1 with DX-L and JAC Admissions,

Attachment 2 with DX-M). Otherwise, the selection process re

mains essentially unchanged. (Tr. 640-641).

The current basic eligibility requirements for application

to JAC are:

a. Age - between 18 and 30. Up to age 35 for men

honorably discharged from the armed services;

k* Possession of a physician's certificate of physical

fitness;

c. United States citizenship or declaration of inten

tion to become a citizen; and

d. Possession of a high school diploma or G.E.D.

(JAC Admiss. No. 13, DX-J).

Applicants who fail to meet each of these requirements are

37/

precluded from further consideration (Adam Deposition at p. 53).

36/ a two-year apprenticeship program was in existence in 1947

(EX. A. at p.l).

37/ it was Plaintiff Rule's failure to meet the high school

diploma requirement that precluded him from further consideration

for JAC in 1966 (Tr. 39 and see p.30, infra) .

-20-

Applicants who meet the above requirements must then take an

38 /

aptitude test and submit to an oral interview conducted by

39 /

a team of two members of JAC (JAC Admiss. No. 14).

In the oral interview, the applicant is asked a series of 40 /

twenty questions for each of which he receives zero or one

point depending on whether or not his answer is satisfactory

to the interviewer. (see JAC Admission No. 20 and Attachment 1).

Zero to ten additional points are awarded based on the inter

viewer's opinion of the applicant's "sincerity of interest and

attitude." (see JAC Admission, Attachment 1). The oral inter

view constitutes up to thirty (30) of the one hundred (100)

possible points earnable on the JAC rating scale (JAC Admission,

Attachment 2).

38 / Oral interviews are conducted once a year (JAC Admiss. No. 15)

39 / Each team consists of one Union and one contractor repre

sentative (JAC Admiss. No. 16).

40 / Among the questions asked are the following:

2. Have you ever taken part in any group activity

such as scouts, sports, etc.

3. Are you now affiliated with any community activity

such as scouting, etc.?

6. Have you ever held a full-time or part-time job?

7. Have you ever been fired from a job? If so, why?

9. What are the duties of an ironworker?

10. Have you ever watched the progress of a construction

job?

13. Do you know the apprentice wages?

-21-

The interviewers also rate and allocate points up to a

fixed maximum based on the following factors:

Factors Maximum Points

Education

Physical Ability

Past Experience

References

REsidence (geographic jurisdiction of JAC) 5

Military Service 5

Finally, an applicant can earn up to 15 points based on

scores received on a battery of aptitude tests (see Attachment 2

to JAC Admiss.). The test battery was first required in 1965

42/

and was administered each year until 1973 when it was dis-

43/

continued pursuant to the Consent Decree (Adam Deposition at

pp. 19-20). It was reintroduced in 1975 (Tr. 620-21).

15-

10

10

10

41/

^ / The applicant automatically received fifteen (15) points if

he possesses a high school diploma or G.E.D.

^ / Between 1965 and 1972, JAC used the Flanigan Aptitude

Classification test (FACT) covering six subjects. In 1972 and

1973, JAC used a similar test battery called the Flanigan

Industrial Test (FIT) (see JAC Admiss Nos. 31 and 32). Between

1965 and 1973, JAC also used a verbal aptitude test in addition

to FACT and FIT (see JAC Admiss. No. 34).

43 / JAC never discontinued the use of these tests. In 1974

it employed the results of the FIT administered by the Missouri

State Employment Service (Ans. to PI. 3d. Interrogs. No. 11 and

Adam Deposition at p. 21). When, in 1975, the Missouri Employment

Service refused to continue testing applicants for JAC, JAC in

formed EEOC of its intention to resume its administration of the

FIT. (Tr. 668). The EEOC failed to require validation and did

not formally object to its reintroduction. (Adam Deposition at

pp. 1925, and TR. 336, 668, 671).

-22-

The applicants' scores on the interview are then added to

44/

the number of points earned on the aptitude test. Applicants

with total rating points above 70 are then ranked in order on

the basis of these scores (JAC Admiss. No. 26). Applicants

with total rating scores of 70 or below are rejected (Id.).

Each year JAC meets and pre-determines the number of

45/

apprentices to be indentured that year and the places are

46/

filled by the applicants with the highest scores. (FF No. 41).

Hence the cut-off score for indenture varies from year to year

(See Tr. 669-670, PX-43 through PX 47 and Ex. A at p. 29). For

example in 1970, JAC indentured 92 apprentices (JAC Admiss. No. 39).

The cut-off score was 80 1/2% (Tr. 613). In 1971, only 11 were

indentured (Tr. 614, JAC Admiss. No. 39). The cut-off score

was 88% (Tr. 615).

44/ A more detailed description of the JAC selection process

and the use of the test battery including a description of how it

is administered, scored and weighed is set forth in the JAC Admis

sions Nos. 31 through 38. Sample copies of the tests themselves

are attached to the JAC Answers to Plaintiffs' Interrogatory

Number 24.

45/ The number of apprentices to be indentured has been the subject

of sharp disagreement between contractors and Union officials. In

1973, the contractors sought indenture of 70 apprentices. The

Union insisted on limiting the number to 20 (Tr. 618-619). After

a series of tie votes, the parties agreed to indenture less than

40 apprentices (Tr. 619).

46/ The consent decree requires JAC to indenture a minimum of

fifteen (15) minorities each year for three years (Consent Decree «[ 9

In order to comply with this requirement JAC adopted the practice

of filling the first fifteen places with the highest ranking minori

ties and then filling the remaining slots with the highest ranking

whites.

-23-

2 . Discriminatory Effect of JAC Selection Process

Blacks have been less successful than whites in gaining

Admission to JAC. The 1970 Census data for the four Missouriizycounties within the territorial jurisdiction of Local 396

discloses that 51.62% of the whites over age 25 have completed

high school as compared to 32.43% of the blacks in the same

age group (JAC Admiss. No. 11). With respect to males 25

years of age and older, 50.63 of the whites have completed high

school (JAC Admiss. No. 11). While the requirement of a high

school diploma for eligibility for JAC was approved in 1964 by

the Bureau of Apprenticeship Training of the U.S. Department of

Labor, it is not job related (See Hunt, Sr. Deposition at p. 107).

Indeed, the possession of a high school diploma has never been a

requirement for obtaining a journeyman ironworker card (Tr. 624).

As the following chart shows, blacks have not performed

as well as whites during the oral interview stage of the admis-

>

sion process.

YEAR WHITE BLACK

NO. OF AVG. MEDIAN NO. OF AVG. MEDIAN

PERSONS SCORE SCORE PERSONS SCORE SCORE

1972 66 28.25 29.50 20 26.95 28.75

1973 105 28.41 29.50 27 27.22 28.00

(JAC Admiss. No. 29).

__41/ Those counties are St. Louis (including the City of St. Louis) ,

Franklin, Jefferson and St. Charles (Seen. 6, supra).

-24-

Nor have black applicants performed as well as white

applicants on the test battery. The average and median rating

points (maximum - 15) of whites and blacks for the years 1972

and 1973 are as follows:

YEAR WHITE BLACKS

NO. OF

PERSONS

AVG.

SCORE

MEDIAN

SCORE

NO. OF

PERSONS

AVG.

SCORE

MEDIAN

SCORE

1972 78 5.76 6.00 25 3.25 3.00

1973 104 6.76 6.00 27 2.92 3.00

(JAC Admiss . No. 37).

As a net result blacks faired less well than whites at the

end

the

of the applicant selection process. The following chart

48 /

average and median total rating scores for all black

shows

and

white applicants who completed the entire application process for

49 /

the years 1972 and 1973.

YEAR WHITE BLACKS

■NO. OF

PERSONS

AVG.

SCORE

MEDIAN

SCORE

NO. OF

PERSONS

AVG.

SCORE

MEDIAN

SCORE

1972 66 83.44 85.00 20 78.22 79.25

1973 103 85.50 85.50 25 79.16 80.00

48/ These are the scores

indenture in JAC.

used in the ranking of applicants for

49/ See also p.13 , supra.

-25-

The exclusion of blacks is further enhanced by the

practice of selecting only those applicants with the highest

scores. The following chart shows the range of scores received

by the 1973 black and white applicants to JAC who received final

rating scores above 70% together with accumulating percentages:

RANGE

SCORES

OF

WHITES

ACCUM.

% WHITE BLACKS

ACCUM.

% BLACK

95-100 4 3.74 0 0

90-94 1/2 25 27.10 2 7.14

85-89 1/2 36 60.75 6 28.57

80-84 1/2 29 87.85 11 67.85

75-79 1/2 10 97.20 4 82.14

70-74 1/2 3 100.00 5 100.00

107

(Attachment 5

28

of JAC Admiss.)

A similar pattern of scores appears for the 1975 class of applicant

RANGE OF ACCUM. 51/ ACCUM.

SCORES WHITES % WHITE BLACKS % BLACK

95-100 22 26.83 4 10.00

90-94 1/2 30f 63.411 3 . 20.00

85-89 1/2 13 79.27 9 50.00

80-84 1/2 10 91.46 8 76.66

75-79 1/2 5 97.56 2 83.33

70-74 1/2 2 100.00 5 100.00

82 30

50/ These figures are derived from the JAC report to EEOC dated

February 21, 1976 which is included in PX-2.

51 / Includes one Spanish surnamed American.

- 2 6 -

Neither the aptitude tests nor any other part of the appren

tice selection procedure has ever been validated in accordance

with the EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedure (See

JAC Ans. to PI. Interro. No. 31 and Tr. 672-673).

E. The Minority Training Program

Like JAC the Ironworker Minority Training Program is adminis

tered by a committee composed of an equal number of contractor and

Union representatives. The MTP was negotiated in August of 1970

(Tr. 402-03). It is regarded as the Union's way of meeting its

Equal Employment Opportunity obligation (Tr. 403). It is

separate and apart from JAC. Effective control of the program

resides in its coordinator who is a journeyman ironworker

(Tr. 448, Myer Deposition at p. 23).

All trainees must be over age 30 (DX-I). Trainees are not

required to have completed high school (Tr. 405). Applicants are

accepted year-round (Tr. 422) but no applicant is indentured into

this program until the program coordinator has found him a job

and he has experienced work in the trade (Tr. 415). Like appren

tices, trainees may not solicit work but must rely on the coor

dinator of the program to solicit for them (Tr. 404).

Although originally conceived as a training program for

minorities over the apprenticeable age (DX-I and Tr. 403), the

MTP is used as a device to segregate blacks and limit their work

and earnings opportunities. It was established as a four-year

program (Tr. 470) . The starting rate for trainees was pegged

at 50% of journeyman's wages (Tr. 417). JAC was and is a three-

-27-

year program. Apprentices were started at 60% of the journey

man wage (Tr. 417). The Union's only justification for imposing

a longer training program and lower starting rate for trainees

was the absence of a high school diploma requirement for

52/

trainees (Tr. 417). In late 1971 the MTP was changed

a three-year program with a 60% starting rate but apprentices

continued to enjoy more favorable wage rates. Trainees were

started at 60% and received 5% increments every six months.

(Tr. 417). Apprentices also started at 60% but received a 10%

JH/increment after the first six months and 5% increments thereafter

Subsequent to the entry of the Consent Decree the MTP was further

changed to accord wage rate parity of trainees to apprentices

(DX-I) .

Upon commencement of the MTP, Local 396 began the practice

of steering all minorities who sought work referral to the MTP

(Ex. A at pp. 44-45). Blacks who were already working on permits

52 / Local 396 concedes that this requirement is not job related.

P- 24 ' supra.

53/ The following chart displays the increments as a percentage

of journeyman's wage to which apprentices and trainees were entitled

to since 1971.

PERIOD APPRENTICES TRAINEES DIFFERENCE

0 - 6 mos. 60% 60% 0%

6 - 1 2 mos. 70 65 5

12 - 18 mos. 75 70 5

18 - 24 mos. 80 75 5

24 - 30 mos. 85 80 5

30 - 36 mos. 90 85 5

(DX-J,

to MTP Ans.

Tr. 417, and Local

to PI. Interrog. No

Area

. 3) .

Contract at p. 10 attached

28-

were forced into the MTP even though they were experienced in the

trade (Tr. 213, 471). The immediate effect was a drastic

reduction in pay. White permitmen continued to work and enjoy

full journeyman wages (Tr. 660). Those blacks who remained as

permitmen found themselves unable to obtain referrals as soon

as the Union implemented the Letter Agreement. (DX-G, 1[ 6 and 11) .

They then joined the MTP (Johnson Deposition at pp. 89-91).

Thus isolated, saddled with the triple disadvantage of

trainee status (see pp.17-19, supra),and condemned to accept lower

wages (see p.14, supra) trainees worked little and earned

less. Predictably, the MTP has suffered from a high turnover

rate. (Quick Deposition at p. 67). During the term of the

Consent Decree the lot of the trainee, as well as minorities in

other classifications was somewhat improved. Minorities were

permitted to solicit, competed with "gualified journeymen" for

referrals and were not subject to automatic layoff before quali

fied journeymen. (Consent Decree).

F• Effects of Local 396 Discriminatory

Practices On The Plaintiffs

On June 16, 1966 (DX-A) Plaintiff Ronald Rule visited the

Union Hall seeking a work permit (Tr. 38). He had been refused

there for a permit (TR. 11) by the Director of the Federal job

54/

Training Program operated by the St. Louis Urban League

54/ The District Court found that Rule was referred to the

Union Hall for the purpose of making application to JAC (F F 1).

Rule was referred by Paul Craig (Tr. 36). Craig referred Rule

for a work permit. (Tr. 11). There was no testimony to the

contrary. At the Union Hall Rule did apply both for a permit

and to JAC. (Tr. 38) .

-29-

(Tr. 10, 14). At the union office he was advised that the

Union was not issuing permits (Tr. 42). In fact there was a

55/

heavy demand for ironworkers. He was permitted to and did

fill out an application for admission to the ironworkers appren

ticeship program (PX-A, Tr. 39). However, he was informed that

he needed a high school diploma, a doctor's statement of physical

fitness and his Army discharge papers (Tr. 39 and F F 2). At

that time he was in good health (Tr. 100) but was one English

course short of meeting the requirements for a high school

56 /

diploma (Tr. 35). In short, he was flatly rejected by the Union.

55 / one contractor described work opportunities in the iron

work trade during that period as follows:

Q. (By Mr. Cronin) Okay. When was the last time

they weren't able to furnish you with a man?

A. Oh, its been — at least three or four years ago.

Q. What kind of men were you looking for on that

occasion?

A. Anybody I could get, somebody that was breathing.

Q. The Union couldn't provide you even one breathing

ironworker?

A. Well we — yes, we had a — quite a spell there —

going back a few years, going back from —

0, I'd say probably from '65 to '69, '64 to '69, that

five-year period there where there were just not

enough people going around and we had a — we brought

in people - we'd have to send them to the Hall first,

though. We'd send them to the Hall, they would issue

them a permit and they would go to work, but we would

send them down there along with a letter or something

of that nature, telling them we had employment, and

they would give them a permit, and we would put them

to work. (Quick Deposition at pp. 19-20) .

56/ He subsequently obtained a G.E.D. in 1971 (Tr. 112).

-30-

He filed a letter charge with the EEOC (PX-3 and F F 3).

He also filed a discrimination charge with the Missouri

Commission on Human Rights. The Missouri Commission commenced

an investigation into Rule's Complaint. The Union then embarked

on a deliberate campaign designed to delay and frustrate reso

lution of Rule's Complaint (PX-26a). Not until some four years

later when it sensed an atmosphere of confusion within the Office

of the Missouri Commission did the Union decide to change its

course and offer a settlement proposal. (PX-26a). On January

20, 1S72 the Union and the Missouri Commission entered into a

Concilation Agreement on Rule's complaint (PX-1 and F F 4).

Neither the Commission nor the Union advised Rule of

the agreement (Tr. 43-44). The Union had duly filed away the

agreement and proceeded to violate its terms (see pp.

infra). But fate intervened. Rule learned of the Conciliation

Agreement during a chance encounter on the street with the

director of the Urban League's federal job training program

(Tr. 15-16, 43-44). Rule then visited the Commission and there

after the Commission contacted the Union and arranged for Rule

to visit the Union Hall for referral (Tr. 44-48 and Johnson

Deposition at pp. 68-73).

-31-

57/

On August 1972 Rule went on his first referral (Tr. 51).

One day later the Union went on strike (Tr. 51, Johnson

Deposition at p. 74) that lasted thirteen weeks (Ex. A at p. 630).

By the end of the strike the Union had successfully negotiated

the Letter Agreement which was incorporated in the contract.

(Ex. A at pp. 63-44). Rule then returned to work at journeyman's

58/

wages (Tr. 52) and the season ended shortly thereafter.

On April 2, 1973 , Rule arrived at the Union Hall for

Referral. He learned that a new system of referrals had been

instituted and that he was no longer eligible for immediate

59/

referral (Johnson Deposition at p . 89). He then left the

Union Hall but returned on another day and discussed his pros

pects for entered JAC or the MTP (Johnson Deposition at p. 91).

60 /

He was too young to qualify for the MTP but William Johnson,

the Union Business Agent, arranged a waiver of that requirement

in Rule's case (Johnson Deposition at pp. 91-92). Rule was

offered the opportunity to enter the MTP and he accepted

(Johnson Deposition at pp. 92-93 , Tr. 57-58). His wages imme

diately dropped to 60% of journeyman wages (Tr. 58). At the

time of trial in April of 1975 he was earning 80% of journeyman's

wages (PX-27).

c n

3 '/ He had been issued a permit and was earning journeyman's

wages (Tr. 52).

_̂ £_/ Work in the inronwork trade is seasonal (Tr. 548) .

Generally, the season runs from March through Thanksgiving (Tr. 548)

C Q3J/ See discussion of Letter Agreement p. 15, supra.

^ / Rule was 29.

-32-

2. Willie West

Plaintiff Willie West had been a member of the laborer's

union since 1960 and was generally familiar with construction

work (Tr. 238). He was not qualified as an ironworker but was

confident he could learn with little training (Tr. 242). In

order to earn more money and obtain better working conditions,

he went to defendant's hall in 1969 seeking referral but was

rejected (Tr. 236, 252). Indeed, no one would even talk to

him (Tr. 253, 237). He returned to the Union Hall a second time,

and was permitted to apply (Tr. 238) and appeared before the

Examining Board (Tr. 253) but was not referred. Subsequently,

in August, 1970, plaintiff West went to the Operating Engineer's

union hall seeking work and was successful (Tr. 264). In 1971,

he was offered admission to the MTP (FF 10) but declined the

invitation because he was earning a higher rate of pay as an opera

ting engineer than the ironworkers were willing to offer. (Tr. 260,24

At the present time he is a journeyman operating engineer.

(Tr. 234), and he is no longer interested in being an ironworker

(Tr. 245).

3. Johnnie I. Brown

Plaintiff Johnnie I. Brown, age 41, had been a switchman

at the terminal railroad until July, 1970 (Tr. 269). Since

worK there was slow, he applied on July 27, 1970 for a referral

(Tr. 269). He was given an application for the MTP which he

-33-

filled out. (PX-15, 270). He was then sent to the office of

Construction Manpower, an organization which was assisting

blacks seeking entry into the construction trade. (Tr. 271).

There, he filled out another application and was told that he

would be contacted but was not. (Tr. 291). He had no prior

ironwork experience (Tr. 275). He quit the railroad in March,

1973, and since then has been employed as a salesman in a retail

clothing store (Tr. 271). He continues to have an interest in

the MTP (Tr. 272) .

4. George Coe

P-*-aintiff George Coe applied for admission to defendant's

JAC on March 18, 1970 (Tr. 281). He took the admission exam

and presented his high school diploma and medical statement

(Tr. 282). Though informed that he had passed the exam, plain

tiff was not admitted to JAC (Tr. 283). His test score was not

sufficiently high (Tr. 586-88). His score was 79 (Tr. 614).

That year the cut-off score was 80 1/2 (Tr. 613). In 1970, JAC

indentured 78 whites and just 2 blacks into its apprenticeship

program (Tr. 611).

5. Hiawatha Davis

Plaintiff Hiawatha Davis, age 29, applied to JAC on May

14, 1973, through the Missouri State Employment Agency (Tr. 302).

He took and passed the examination given by JAC but did not submit

a medical statement because he was discouraged, having been

advised that he might be required to move out of the State in

order to find work (Tr. 307).

34-

6. Lonnie R. Vanderson, Jr.

Plaintiff Lonnie R. Vanderson, Jr., age 29, applied for

admission to JAC on October 29, 1974 (Tr. 318). Plaintiff took

and passed the exam with a score of 71 or 72 (Tr. 319 and PX-2).

As of the time of trial, he had neither been accepted or rejected

by JAC (Tr. 590-91). However, on the most recent list of appren

tice applicants, he ranks number 109 of 111 applicants (PX-3,

JAC Report of Feb. 21, 1975).

7. Willie Nichols

Plaintiff Willie Nichols applied for admission to the

MTP in February, 1973 (Tr. 694). He has never been contacted

by Local 396 or its MTP (Tr. 694). On his own initiative, he

has sat in on classes at the MTP and has checked on ironwork

jobs (Tr. 706) .

-35-

ARGUMENT

The facts underlying the issues raised in this appeal are

the now familiar pattern of racial discrimination in the building

construction trades. E.g., see United States v. Sheet Metal

Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969); United States v.

Ironworkers, Local 10, ___ F. Supp. ___, 6 F.E.P. Cases 59 (W.D.

Mo. 1973); United States v. Local 86, Ironworkers, 315 F. Supp.

1202 (W.D. Wash.), aff'd 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir. 1971), cert, denied

404 U.S. 984 (1971).

Present here are issues involving the district court's

refusal to permit the case to' proceed as a class action, its

refusal to consider certain evidence offered by plaintiffs, its

refusal to enter findings of unlawful discrimination against the

named plaintiffs and the attendant denial of relief, and the refusal

to consider clear evidence of multiple violations of agreements

entered into with two governmental agencies for the benefit of the

plaintiffs and other blacks who were the victims of the defendants'

unlawful practices. The district court declined to consider plain

tiffs' class-wide claims and rejected plaintiffs contentions

regarding the effects of those practices on the plaintiffs. Below

plaintiffs discuss those practices in the context of plaintiffs'

individual claims since their effects on plaintiffs have been

direct and substantial. However, plaintiffs seek relief not only

for themselves but for the members of the class as well. Defen

dants' violations of the conciliation agreement is treated along

with plaintiffs' request for review of the district court's refusal

to grant plaintiffs' request for enforcement.

-36-

I. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DECERTIFICATION OF THE

CLASS CONSTITUTES AN ABUSE OF DISCRETION.

A statement of the proceedings leading up to the certifica

tion of the class order of July 18, 1974, and the subsequent decer

tification of the plaintiff class is set forth at pp. 2-3, supra.

As of December 20, 1974, when the district court decertified the

class, there were at least 323 persons in the class. The district

61/

court was fully aware of that fact but nevertheless chose to

decertify the class and limit further participation in the case to

the 17 class members who affirmatively sought inclusion (Order of

December 20, 1974). That decision was a clear abuse of discretion.

See Knuth v. Erie-Crawford Dairy Coop. Assn., 395 F.2d 420, 428

(3d Cir. 1968).

It must be remembered that the district court had previously

held an evidentiary hearing on plaintiffs' class action application

and had entered specific findings that plaintiff had met all of the

requirements of Rule 23, F.R.Civ.P. (see Memorandum of July 18,

1974). There was no subsequent evidence or finding that plaintiff

at any time failed to meet all of the requirements of Rule 23(a)

62/

as well as the requirements of Rule 23(b)(2), or (b)(3). Of the

61/ The district court wrote:

The Court is of the opinion, in spite of the fact that

the notice stated that those not responding would be

included in the class, the number indicating a desire

to be included is so small in relation to the entire

possible class that the request to make this a class

action is denied. (Order of December 20, 1974).

62/ Whether or not the district court intended to certify the class

under Rule 23(b)(2) is unclear. The district court's citation of

Carr v. Conoco Plastics, Inc.. 295 F. Supp. 1281 (N.D. Miss. 1969)

suggest that the court had a (b)(2) certification in mind but its

notice to the class permitted class members to "opt-out" which

-37-

approximately 460 class members, 381 received notices (see December

20, 1974 Order). Just thirteen percent (13%) of those who received

notices requested to be excluded. This fact alone is not an ade

quate basis on which to ground a decertification decision. At no

time did the court express any doubt as to plaintiffs' ability to

63/

adequately represent the remaining 323 class members (Order of

December 20, 1974). Nor did the court find that the requirement

of numerosity had not been met. Clearly, it is impracticable to

join over 300 people as named plaintiffs. See Sagers v. Yellow

Freight Systems, Inc.. 529 F.2d 721, 734 (5th Cir. 1976).

The impracticability of joining all of the remaining class

members is illustrated by the difficulty plaintiffs' counsel