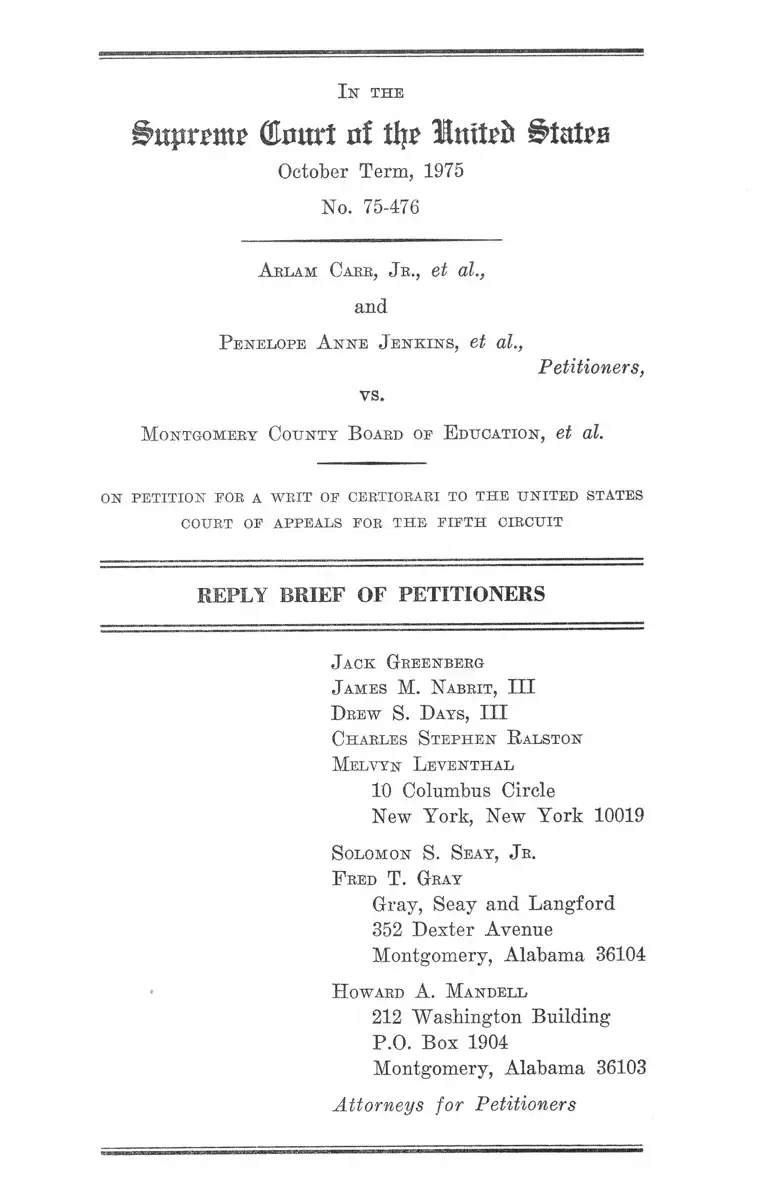

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Reply Brief of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Reply Brief of Petitioners, 1975. 1eb0b1e8-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ca8e7338-e687-4061-af17-c4a0e5d4fa4f/carr-v-montgomery-county-board-of-education-reply-brief-of-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

^ t r p m n e © H u rt ni % H u ffe d S t a l l 's

October Term, 1975

No. 75-476

A rlam Carr, J r ., et al.,

and

P enelope A n n e J e n k in s , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

M ontgomery C o u n ty B oard op E ducation , et al.

on petitio n eoe a w r it oe certiorari to t h e u n ited states

court oe appeals eor t h e e ipt h circuit

REPLY BRIEF OF PETITIONERS

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

D rew S. D ays , III

C harles S teph en R alston

M elvyn L even th al

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

S olomon S. S eay , Jr.

F red T. G ray

Gray, Seay and Langford

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

H oward A. M andell

212 Washington Building

P.O. Box 1904

Montgomery, Alabama 36103

Attorneys for Petitioners

I k t h e

(Horn*! Hi tffp Inttefo States

October Term, 1975

No. 75-476

A klam Carr, Jh., et al.,

and

P enelope A n n e J e n k in s , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

M ontgomery C o u n ty B oard of E ducation , et al.

on petitio n for a w r it of certiorari to th e u nited states

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF OF PETITIONERS

Introduction.

In their Brief in Opposition1 the respondents argue, in

essence, that this Court should not grant a writ of cer

tiorari herein for the following reasons:

1. The Board has continually acted in good faith in at

tempting to meet its responsibility to desegregate;

1 References to the Brief in Opposition will be noted as (Res.

Br. — ).

2

2. The trial judge was correct in finding that the remain

ing all-black schools were not vestiges of the dual

system;

3. Plans submitted by petitioners for achieving greater

desegregation of the remaining one-race schools were

impractical and designed with impermissible goals in

mind (“racial balance” ) ; and that

4. The Board’s plan achieves meaningful desegregation

in a fashion that does not unduly burden blacks.

Point two above has been dealt with at length in our brief

in chief which establishes, we submit, that the remaining

all-black elementaries have been all-black since a state-

imposed dual system was sanctioned by law in Montgomery

County.2 We would like to take this additional opportu

nity, however, to address points one, three and four in

order to correct certain material misstatements and in

accuracies in the Brief in Opposition.

Argument

Petitioners do not seek to quarrel here over the question

of whether the Montgomery County Board of Education

has acted in good faith in carrying out its constitutional

duty to dismantle its dual system of segregated schools.

For “good faith” is simply not at issue in this litigation or

in any school desegregation case, for that matter. The

central issue turns, rather, upon the answers to factual

questions, as ths Court has pointed out so often: Is the

desegregation plan under consideration one “that promises

realistically to work nowV’ Green v. County School Board

of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968); does the

plan “achieve the greatest possible degree of actual de

2 Petition for a Writ of Certiorari at 12-21.

3

segregation?” Stvann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 26 (1971).

As the most recent enrollment statistics for the 1975-76

academic year in Montgomery County reflect, the answers

to both the foregoing questions must be in the negative.3

According to this report, 35,211 students are enrolled in

the Montgomery County system for the current academic

year, of which 17,029 are black and 18,182 are white. Out

of the total black enrollment, 8484 are attending elementary

schools. And of this number, 5011 or 59% are enrolled in

facilities that are 85% or more black. The following chart

indicates with more specificity the schools and black ratios

which vividly attest to the continuing dual nature of

elementary education in Montgomery County:

Black White

School Enrollment Enrollment % Black

Bellinger Hill 188 34 85

Booker Washington 234 3 99

Carver 393 9 98

Daisy Lawrence 363 5 99

Davis 678 47 94

Dunbar 296 38 89

Fews 643 1 99.9

Hayneville Road 713 22 97

Loveless 823 1 99.9

Paterson 516 21 97

Pintlala 164 13 93

Totals4 5011 193

3 A copy of the Board’s “ Report to the Court” of September 24.

1975 is attached hereto as an appendix for the Court’s benefit.

4 This total does not include elementary students attending

Bellingrath which serves junior high school students as well since

no breakdown by grade is given in the Report. The total black-

white enrollment is 858 black and 232 white.

4

Plans submitted by petitioners were deficient, the Board

asserts, first, because they relied upon non-contiguous pair

ing and clustering and rezoning to achieve greater de

segregation and, secondly because they were designed with

an eye to achieving an impermissible racial balance among

schools in the system. Non-contiguous pairing and cluster

ing have been sanctioned by this Court as viable tools for

achieving a unitary school system. Swann, supra. The

fact that a system must alter grade structures in its schools

from the traditional 1-6, 7-9, 10-12 arrangement to accom

modate desegregation in this fashion is of no constitutional

moment. Moreover, the Board undoubtedly intends in its

brief to leave the false impression, as did the trial court

in its opinion, that petitioners’ plans involved travel times

and distances far out of line with transportation of stu

dents prior to 1974 and under its own “desegregation plan” .

The facts are otherwise. Under the plan approved by the

district court in 1970, a significant number of students

transported lived in so-called “periphery zones” in rural

Montgomery County and were bused to schools in the City.

During the 1973-74 academic year, the longest one-way

bus-trip was 46 miles and a number of trips exceeded 30

miles one way. Most of the children bused under this ar

rangement traveled more than 10 miles one way; and the

shortest distance any child traveled was 6 miles one way.

Under the plan approved by the district court currently in

force some black children are bused distances of nine and

twelve miles each way.

In contrast, petitioners’ plans envisioned transportation

times and distances often far below those previously or

presently approved by the Board and district court. It

must be remembered that of those all-black schools listed

in the chart at page 3 supra, only Dunbar and Pintlala

are located outside of the City of Montgomery. The City

5

of Montgomery at its furthest extremities is about 12 miles

from west to east and 10 miles from north to south. Move

ment from point-to-point in any direction within the city

limits is facilitated by the existence of two major freeways.

It has no major natural or man-made obstacles to trans

portation within its limits. Given these facts, the following

times and distances in petitioners’ plans for desegregating

the city elementary schools are not surprising:

1. Under the plan of petitioners Carr, et ah, the longest

distance and time between paired schools would have

been 10 miles and 30 minutes, involving two schools

at the extreme opposite ends of the City. Other pair

ings would have required less travel;

2. Under the plans of petitioners Jenkins, et al. the

longest route within the city would have been 7.3 miles

and 18 minutes. And, if certain satellite zone features

of the plans had been discarded (an option available

to the trial court), routes would have rarely exceeded

5 miles. The average travel distance under these

plans would have been 4-5 miles.

In light of these figures the Board’s reliance upon North-

cross v. Board of Education of Memphis, 489 F.2d 15 (6th

Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 962 (1974) seems ill-

founded. There the lower courts rejected as unreasonable

a plan that would have transported students between 46-60

minutes one way. As in Swann v. Charlotte-MecJclenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), where this Court

approved student transportation averaging about seven

miles and taking not over 35 minutes, Id. at 30, transporta

tion times and distances in petitioners’ plans fell well

within the bounds of previous busing arrangements and

often fell below the Board’s projections under its own plan.

The Board has, nevertheless, joined the trial court in ig

6

noring this Court’s directive in Swann to evaluate trans

portation plans in terms of whether “the time or distance

of travel is so great as to either risk the health of the

children or significantly impinge on the education process.”

The district court’s bald assertion that pairings and

clusterings “would substantially increase the time and dis

tance that students would have to travel” 5 and emphasis

upon the number of students to be transported under the

respective plans, which the Board echoes in its brief,6 are

plainly attempts to avoid the facts vindicating petitioners’

position.

It is also suggested by the Board that petitioners’ plans

were constitutionally defective because they sought to

achieve racial balance to the detriment of all other reason

able considerations. In actuality, petitioners’ plans did

no more than rely upon this Court’s approval in Swann,

supra of the use of system-wide ratios as starting points

in any reasonable attempt to desegregate a dual system.

Racial balance was not the objective of nor was it the result

achieved by petitioners’ plans. In the City of Montgomery,

racial ratios under the plan of petitioners Carr, et al.

ranged from 24% black to 66% black. And under the plans

of petitioners Jenkins, et al. black percentages were 84%

to 27% black and 100% to 7% black respectively. The

Board’s brief itself establishes that the “racial balance”

charge leveled at petitioners’ plans is spurious by ac

knowledging that some all-black schools and racially-

identifiable schools were left under all Submissions.7 Hence,

on yet another issue, the district court and Board have

characterized petitioners’ plans in a fashion at odds with

the factual record.

5 Appendix to Petition p. 16a-17a.

6 Res. Br. 30.

7 Res. Br. 36, 40, 47.

7

The Board has also attempted to convey the impression

that its desegregated plan does not impose undue burden

upon blacks nor transport blacks disproportionately. It

does so by pointing out that “2401 white children [are]

transported to schools which are predominantly black or

would be predominantly black without the white transporta

tion involved,” 8 that several formerly all black schools will

become predominantly white,” 9 and that “no white child

is transported past a majority black school to a majority

white school.” 10 We would respectfully submit that the

Board’s references are entirely to transportation or as

signment of white junior high or senior high students. It

remains true, nevertheless, that no white elementary child

is bused to increase desegregation and that whites bused

as part of the plan are sent to majority white schools, often

by-passing closer majority black schools in transit.11 The

Board plan, in fact, envisioned a decrease in elementary

school transportation. In 1973-74, the Board transported

5,388 elementary students of which 3,177 or 59% were

black. Under the plan presently in effect, 4,465 elementary

students were to be transported, of which 3,157 or 71%

were to be black. As a result, 903 fewer white students and

only 2 fewer black students were to be bused in 1974-75 as

compared to 1973-74 figures.12 That the transportation of

8 Res. Br. 19.

9 Res. Br. 22.

10 Id.

11 For example, 130 black children and 14 white children who

previously attended Chilton, a school closed under the Board’s

plan, are being transported four and five miles to Head Elemen

tary and Dalraida Elementary, majority-white schools even though

Bellinger Hill, Booker Washington, Fews, Loveless and Daisy

Lawrence are within walking distance of the Chilton zone.

12 Much of the reduction in white elementary student transpor

tation can be attributed to the construction of two new elementa-

ries, Vaughn Road and Eastern By-Pass (now Dozier), at the

eastern edge of Montgomery City.

solely blacks for purposes of elementary desegregation was

a consequence of the Board’s concern for “white flight”

was not, contrary to the assertion in its brief, a rationale

of petitioners’ creation. The testimony quoted below of Mr.

Silas Garrett, Superintendent of Schools for the Mont

gomery system, on this point is dispositive, we submit:

The Court: His question is why doesn’t the Board

propose to transport white students to predominantly

black [elementary] schools? He says under your plan,

there is [sic] no instances where you do that.

Witness: Oh.

The Court: Is there a reason? That is his question.

Witness: Yes, sir: Our reason is this; that we do

not believe that white children so assigned would at

tend in any substantial numbers. And, here again, it

would, in our opinion, be an operation in futility, and

it would not further the overall desegregation of this

school system.13

In order to avoid potential white flight, therefore, the

Board’s plan was designed such that only one elementary

school out of 33 was projected to be between 40-60% white;

twenty schools were projected to be between 60-80% and

eleven schools were projected to be between 0-19% white.

The pattern is one of arranging for the maintenance of

60% or better white schools or virtually all-black schools.

In sum, the Board, not petitioners, was concerned about

“racial balance”—to avoid anticipated white flight—in

structuring its plan.14

13 Tr. p. 240 (April 24, 1974 hearing). Similar testimony oc

curs at Tr. pp. 251-52 with respect to the potential for “a white

exodus.”

14 Cf. Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 434 F.2d 408,

411 (4th Cir. 1970) cert, denied, 399 U.S. 929 (1970).

9

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, petitioners respectfully sub

mit that a writ of certiorari should be granted in this

cause.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

D rew S. D ays , III

C harles S tephen - R alston

M elvyn L even th al

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

S olomon S. Seay, Jr.

F red T. G ray

Gray, Seay and Langford

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

H oward A. M andell

212 Washington Building

P.O. Box 1904

Montgomery, Alabama 36103

Attorneys for Petitioners

A P P E N D I X

EXHIBIT "A

MONTGOMERY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

M ontgom ery, Alabama

A REPORT TO THE FEDERAL COURT

Septem ber 1 5 , 1975

SCHOOL

NORMAL

CAPACITY

ACTUAL ENROLLMENT

BLACK WHITE

NO. FACULTY

BLACK WHITE

B aldw in 780 457 54 11 17

Bear 630 183 346 0 14

B e l l in g e r H i l l 300 188 34 5 6

B e l l in g r a t h 1 ,2 3 0 * 853 232 17 26

B ooker W ashington 420 234 3 6 6

C a p ito l H e ig h ts E le . 570 128 191 6 8

C a p ito l H e ig h ts J r . 1 ,2 0 0 314 662 17 23

C arver E le . 780 393 9 8 9

C arver J r . 660 350 547 16 18

C arver S r . 1 ,1 0 0 * * 773 645 24 41

Catoma 240 52 125 3 4

Chisholm 810 331 478 15 19

C lo v e r d a le 1 ,1 7 0 445 832 17 30

Crump 990 219 775 16 22

D aisy Lawrence 720 363 5 8 9

Da I r a id a 630 116 389 9 13

Dannel.ly 780 220 495 11 17

D avis 630 678 47 14 17

D oz ie r 750 120 712 15 17

Dunbar 660 296 38 8 9

lew s 720 643 1 14 15

F low ers 780 150 522 11 16

Floyd 1 ,3 5 0 * 416 695 16 27

F o re s t Avenue 480 120 248 8 10

G eorg ia W ashington 1 ,2 9 0 428 1 ,0 1 0 21 34

Goodvyn 1 ,5 0 0 586 902 22 32

H a rr ison 750 283 393 13 16

H a y n e v ille Road 1 ,2 0 0 713 22 13 18

Head 690 107 481 10 15

H igh lan d Avenue . 390 106 211 5 9

•Highland Cardens 1 ,0 2 0 287 485 15 18

H ouston K i l l J r . 570 263 350 10 16

J e f f e r s o n D avis 2 ,1 0 0 832 1 ,4 8 6 37 62

Johnson 660 123 484 9 16

L a n ier 2 ,2 5 0 737 739 23 46

Lee 2 ,3 0 0 889 1 ,6 1 0 36 73

L o v e le s s 1 ,1 4 0 823 1 16 20

M acM illan 390 205 69 6 7

M cIn tyre .1 ,5 0 0 802 20 15 16

M ontgomery Co. High* 570 392 55 8 17

M orningview 600 99 445 10 14

P a terson 810 516 21 11 14

P e te rso n 600 119 320 8 11

P in c la la 270 164 13 3 6

South lawn 840 314 375 13 14

■‘aughn Road 750 194 608 14 19

* Combined e lem en ta ry

••’•'•Six rooms n o t nceclei

and ju n io r h igh

■l in the e lem en tary program are used by the s e n io r h igh s c h o o l

MEILEN PRESS IN C — N. Y. C 219