Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education Emergency Motion for Injunction Pending Appeal

Public Court Documents

August 24, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education Emergency Motion for Injunction Pending Appeal, 1987. 91a2af41-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ca8ee22e-4ce7-4892-9f69-099167d9c2d3/stout-v-jefferson-county-board-of-education-emergency-motion-for-injunction-pending-appeal. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

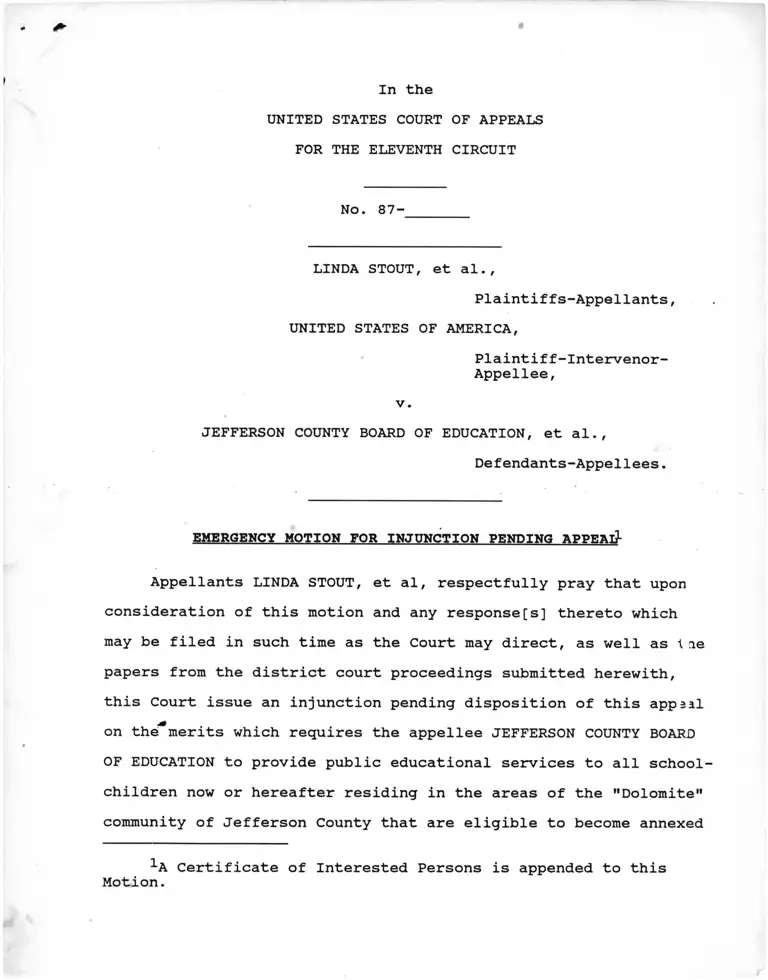

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-

LINDA STOUT, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-

Appellee,

v.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

EMERGENCY MOTION FOR INJUNCTION PENDING APPEAL

Appellants LINDA STOUT, et al, respectfully pray that upon

consideration of this motion and any response[s] thereto which

may be filed in such time as the Court may direct, as well as \ le

papers from the district court proceedings submitted herewith,

this Court issue an injunction pending disposition of this appeal

on the-merits which requires the appellee JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD

OF EDUCATION to provide public educational services to all school-

children now or hereafter residing in the areas of the "Dolomite"

community of Jefferson County that are eligible to become annexed

-'-A Certificate of Interested Persons is appended to this

Motion.

to the City of Birmingham, Alabama upon pre-clearance by the Attor

ney General under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973c.

Appellants respectfully seek emergency consideration of this

request by the Court. Absent the issuance of the relief sought

herein, members of the class of black students residing in the

said areas of the "Dolomite" community will be excluded from the

Jefferson County public schools which they have previously attended

(through the conclusion of the 1986-87 school year) unless they

can afford tuition in excess of $450 per year, and they will be

required to attend the public schools of the City of Birmingham,

Alabama. Classes for the 1987-88 school year will begin on August

31, 1987.

In support of their request, appellants would respectfully

show the Court as follows: 1

1. This litigation to desegregate th» public schools of Jef

ferson County, Alabama, has a lengthy hisiory. In proceedings

particularly relevant to the current coniroversy, the Fifth Circuit

in 1971 vacated and remanded for implementation of a plan consistent

with Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenbura Boari of Education. 402 U.S.

1 (1971) and instructed that "[t]he district court shall include

within its order a direction to any school boards created since

the filing of the original action in this cause to submit to the

plan to be approved by the district court." Stout v. Jefferson

County Board of Education. 448 F.2d 403, 404 n.l (5th Cir. 1971).

2

2. This instruction was necessary because a number of all-

white or virtually all-white cities within Jefferson County which

had not previously sought to operate separate school systems

attempted to do so when meaningful pupil desegregation began to be

reguired. One such municipality ultimately enjoined from operating

a separate system (because it refused to assign students as part

of a countywide plan approved by the federal court) was Pleasant

Grove, Alabama. See Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education.

466 F.2d 1213, 1214-15 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied. 411 U.S.

930 (1973); City of Pleasant Grove v. United States. 568 F. Supp.

1455, 1457 (D.D.C. 1983); id.. 623 F. Supp. 782, 787-88 (D.D.C.

1985), aff'd ___ U.S. ___, 93 L.Ed. 2d 866 (1987).

3. Pursuant to the desegregation plan approved by the district

court in 1972, as modified in respects not material to this contro

versy, students residing in the predominantly black, unincorporated

area of Jefferson County, Alabama known as "Dolomite" have been

assigned to the "Pleasant Grove Attendance Area" of the county

school system, and Jiore specifically in the 1986-87 school year

to Pleasant Grove E. ementary School for grades 1-3, Woodward

Elementary School f-.r grades 4-6, and to Pleasant Grove High School

for grades 7-12. (See Plaintiffs' Exhibit 1 & Defendants' Exhibit

1 introduced at August 17, 1987 hearing on Motion for Temporary

Restraining Order.2)

2With the agreement of counsel, the district court pursuant

to F.R. Civ. P. 65(a)(2) treated the hearing on the request for a

temporary restraining order as the hearing on the motion for pre

liminary injunction and consolidated it with the trial on the

3

4. The Dolomite community, whose children attended schools

in the "Pleasant Grove Attendance Area" pursuant to the district

court's orders, attempted to obtain necessary governmental services

by petitioning for annexation to the City of Pleasant Grove. The

City of Pleasant Grove refused to annex the area and terminated

fire and paramedic protection to the Dolomite community which it

had previously provided. City of Pleasant Grove v. United States.

568 F. Supp. 1457, text at n.9; id.. 623 F. Supp. 783, text at

n.3; id.. 93 L. Ed. 2d 866 n.4.

5. The refusal of the City of Pleasant Grove to annex nearby

predominantly black unincorporated areas of Jefferson County,

including the Dolomite community, while pursuing annexation of

nearby predominantly white areas, has been found to violate § 5

of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c, because it was

racially motivated. City of Pleasant Grove v. United States. 623

F. Supp. at 788, aff'd ___ U.S. ___, 93 L. Ed. 2d 866 (1987).

6. The Dolomite community also attempted to annex to another

predominantly white municipality in Jefferson County, Hueytown,

merits of plaintiffs' motion for further relief. (See Transcript

of Oral Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law Before Hon. Sam

C. Pointer, Jr., p. 12.)

Pursuant to Eleventh Circuit Rule 27-l(b)(2), copies of the

district court papers are being submitted along with this motion.

Plaintiffs' moving papers, relevant exhibits, and the transcript

of the district court's oral Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law accompany this motion. The Minute Entry recording the district

court's judgment is being forwarded separately from co-counsel in

Montgomery. Counsel for appellants has ordered the complete tran

script from the court reporter.

4

without success. Thereafter, following a major fire emergency in

which five persons were killed, two separate areas of Dolomite

petitioned for annexation to the City of Birmingham in 1987. On

April 10, 1987 the Judge of Probate of Jefferson County, Alabama

entered an Order of Annexation with respect to one such area,

following an annexation election held March 21, 1987 pursuant to

§ 11-42-2 of the 1975 Code of Alabama. On June 2, 1987, by

Ordinance No. 87-88, the City of Birmingham annexed the second

area. (See Plaintiffs' Exhibits 4 & 5 introduced at August 17,

1987 hearing on Motion for Temporary Restraining Order.)

7. On July 15, 1987, the City of Birmingham submitted these

and three other .annexations to the United States Department of

Justice for pre-clearance under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

(See Plaintiffs' Exhibit 4 introduced at August 17, 1987 hearing.)

The Attorney General has not yet acted upon the Dolomite submis

sions. Under the statute, the Attorney General is not required

to act until 60 days after receipt of the submission (or at the

least, in this case, until approximately September 15, 1987), and

under regulations promulgated to implement § 5, he may request

further information, the receipt of which will trigger a new 60-

day period for determination. See 28 C.F.R. §§ 51.25(p), 51.35(a),

51.37 (1986); Georgia v. United States. 411 U.S. 526, 538-41 (1973).

8. Despite the fact that the Attorney General has not yet

acted, the Jefferson County Board of Education notified the parents

of students residing in the two areas of Dolomite referred to

5

above that they would not be admitted to Jefferson County public

schools for the 1987-88 school year without payment of tuition

but must attend schools in the City of Birmingham school system.

(See attachment to Plaintiffs' Exhibit 12 introduced at August 17

hearing [affidavit of Jesse Vann, Sr.].)

9. On August 12, following unsuccessful attempts to resolve

the matter without litigation (see Affidavit of Richard Arrington,

Jr. in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Temporary Restraining

Order, filed August 12, 1987) plaintiffs filed a Motion for Further

Relief seeking preliminary and permanent injunctive relief, and a

Motion for Temporary Restraining Order on August 12, 1987.3 A

hearing was held before the Hon. Sam C. Pointer, Jr., Chief Judge

of the United States District Court for the Northern District of

Alabama, on August 17, 1987, which became the hearing on the merits

of plaintiffs' Motion for Further Relief..4

9. The district court found, based upon the uncontested evi

dence offered by the Jefferson County Board of Education, that if

the students residing in the Dolomite areas refe rred to above are

removed from the Jefferson County school system — and in particular

from the Pleasant Grove Elementary, Woodward Elenentary, and

Pleasant Grove High, schools — there will be

a significant effect on the school populations

of the three schools from which these students

3The City of Birmingham, Alabama appeared as amicus curiae

in the district court in support of plaintiffs' request for relief.

4See supra note 2.

6

would be drawn. The ratio of white to black

studenjts at these three schools in the Jef

ferson County system as of the end of the

last school year ranged from seventy-one percent

white to eighty percent white. As a result

of the annexation and loss of these students,

those figures for the next year, absent transfer

with tuition payments, would be in the range

of ninety-four to ninety-seven percent white.

There is then a potential impact on the deseg

regation plan and efforts and activities of

the Jefferson County school system.

(Oral Findings of Fact and Conclusion of Law Before Hon. Sam C.

Pointer, Jr., at pp. 5-6.)

10. The district court refused to enjoin the Jefferson County

Board of Education to continue educating the students from the

two areas of the Dolomite community "until such time as the Jef

ferson County School System is judicially declared to be 'unitary'

and the 1985 and 1987 annexations of the Dolomite Community into

Birmingham, Alabama have been 'pre-cleared' by the United States

Attorney General"5 because the Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion did not cause the annexations (Oral Findings, p. 6), because

the policy which the Jefferson County Board is applying has been

consistently applied to prior annexations (Oral Findings, p. 8),

and because the court wished to treat the black students in these

areas in the same fashion as it had when responding to requests

by white students for exemption from assignment changes (Oral

5See Plaintiffs' Motion for Further Relief filed August

12, 1987, at pp. 1-2.

7

Findings, pp. 3-4).6 Plaintiffs filed their Notice of Appeal to

this Court on August 21, 1987.

11. Under these circumstances, plaintiffs-appellants are

entitled to relief pending plenary adjudication of their appeal,

because (a) they are likely to succeed on the merits; (b) they

will suffer irreparable injury if relief is not granted; (c) the

Jefferson County Board of Education will suffer no harm if relief

is granted; and (d) the public interest in effectuating plaintiffs'

constitutional rights strongly supports issuance of the relief.

See, e.q.. Jean v. Nelson. 683 F.2d 1311 (11th Cir. 1982)(per

curiam); Eleventh Circuit Rule 27-l(b)(l):.

6Although the district court stated that he had

as an individual judge, since 1971 had to face similar

issues over the years. Students displaced by changes

in attendance zones, either by court order or as a result

of annexation, have periodically come before this Court

for special relief. They have asserted, and this Court

has certainly understood, that the displacement of stu

dents from the schools with which they have been

associated, from their teachers, their classmates and

from their activities, certainly has a disruptive effect

on the educational process, and certainly on the emotional

health of students. To have this matter come up in

1987 is no less difficult than it was in 1971 or '72 or

'73. Most of the earlier requests for special relief

came from white children. More of the later requests

have come from black children and their parents

(Oral Findings, pp. 3-4), a review of the Docket Entries fails to

disclose that the court has been faced with repeated requests

over the years, and especially during the last decade. In any

event, there is a considerable difference between the requests

from white students and parents in the early 1970's, who sought

to avoid attending integrated schools, and the relief sought by

the Dolomite students and their parents, who wish to continue to

attend integrated schools.

8

(a) Appellants are likely to prevail on the merits for

two reasons. First, until the annexations have been pre

cleared by the Attorney General or the City of Birmingham

obtains a declaratory judgment from the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia (which it has not sought),

they may not be implemented. 42 U.S.C. § 1973c. This statu

tory mandate is not limited to matters such as allowing resi

dents of the areas in question to vote in Birmingham city

elections but extends to policies of the Jefferson County

Board of Education purporting to recognize the annexations

prior to their pre-clearance. Cf. Dougherty County Board of

Education v. White. 439 U.S. 32 (1978). As the request for

injunctive relief in plaintiffs' Motion for Further Relief

recognized, it is plainly illegal for the Jefferson County

Board of Education or any other agency of the State of Alabama

to give effect to the annexations until they are pre-cleared

or approved by a three-judge district court in the District

of Columbia.

Second, the substantial effect of withdrawing the Dolo

mite students from the Jefferson County schools which they

have attended, up until the end of the 1986-87 school year,

is uncontested and was specifically found by the district

court. Permitting this withdrawal will in effect recreate

the situation which the City of Pleasant Grove sought to

establish in 1971 through secession from the Jefferson County

system (that is, virtually all-white schools serving its

9

students). Because the Jefferson County system is not yet

unitary. Brown v. Board of Education of Bessemer. 808 F.2d

1445, 1446 (11th Cir. 1987), the district court's authority

to require that the Jefferson County school system continue

to educate the students in the Dolomite area is not dependent

upon a finding that the Jefferson County Board of Education

is responsible for the annexations; the negative effect of

the annexations upon the status of desegregation in the county

schools (and particularly those in the Pleasant Grove Attend

ance Area) is sufficient. Id. at 1447-49.

Relief similar to that which was sought below, and is

now sought here, was granted last year in Brown v. Board of

Education of Bessemer following annexation of areas of Jef

ferson County, Alabama into the City of Bessemer. The court

below emphasized that of the two annexation parcels in the

Bessemer case, only students who resided in the one in which

a county school building was located were required to be con

tinued in the Jefferson County school system (OraL Findings,

pp. 7-8). That was not the basis for the distric.; court's

different treatment of the two parcels in the Bes semer liti

gation, however. There the court distinguished tie two situ

ations based upon the effect on school deseareaavion in both

the Bessemer and Jefferson County systems:

[R]elief is due to be GRANTED with respect to the school

children now or hereafter residing in the geographical

areas of Parcel B recently annexed to the City of

Bessemer, Alabama, but is due to be DENIED with respect

to the school children now or hereafter residing in the

10

geographical areas of Parcel A recently annexed to the

City of Bessemer. 10/

10/ The Bessemer Board concedes in post-hearing brief

that the immediate influx of some 212 students

from Parcel A into the Bessemer City School System

will not disrupt its proposed unitary plan and

would produce no significant impact on the racial

percentage makeup of students in the affected Jef

ferson County schools or in the Bessemer City

schools.

(Memorandum of Decision, Brown v. Board of Education of Bes

semer. No. CV 65-HM-0366-S (N.D. Ala. Aug. 15, 1986) at p.

57. Here, the district court recognized the "significant"

impact on the affected Jefferson County schools7

Even if an "inter-district" violation were required,

see id. at 1447-48, that standard can be met in this case.

In Milliken v. Bradley. 418 U.S. 717, 753, 755 (1974), Justice

Stewart wrote in his concurring opinion that "[w]ere it to

be shown, for example, that state officials had contributed

to the separation of the races by drawing or redrawing school

district lines . . . then a decree calling for transfer of

pupils across district line.'; or for restructuring of district

lines might well be appropriate." Pleasant Grove officials

are state officials for purposes of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, and but for their rao.ally motivated refusal to annex

the Dolomite area it would remain in the Pleasant Grove/

Jefferson County school system today and the 1987 election and

7This was the correct analysis. See Lee v. Lee Countv

Board of Education. 639 F.2d 1243, 1262 n.13 & cases cited (5th

Cir. 1981).

11

petition for annexation to Birmingham would never have taken

place. Thus, state actors have for racially discriminatory

reasons contributed to the significant changes in racial

composition of schools in the Jefferson County school system

which will result from the Dolomite annexations to Birmingham.8

(b) The equities weigh heavily in favor of the appellants,

and in this Circuit will justify issuance of the relief sought

even if the Court is not convinced that appellants will prevail

on the merits but believes only that they have presented a

"substantial case on the merits." Garcia-Mir v. Meese. 781

F.2d 1450, 1453 (11th Cir. 1986); id. at 1457 (Clark, J.,

concurring); Ruiz v. Estelle. 650 F.2d 555 (5th Cir. Unit A

1981).

Here, appellants and the other pupils residing in the

Dolomite areas face immediate, substantial and irreparable

injury. If an injunction pending appeal is not granted,

they will either be required to leave the integrated schools

which "hey have for years attended; to interrupt their courses

of stv ly, their extra-curricular activites, and relationships

with teachers and friends (see Plaintiffs' Exhibits 13-16

introduced at August 17 hearing [affidavits of students]);

and to be reassigned to schools that "will be almost exclu

sively, if not exclusively, black, within the school system

of the City of Birmingham" (Oral Findings, p. 5), or they

8See Lee v. Lee County Board of Education. 639 F.2d at 1264-69.

12

will be required to expend funds for tuition payments to the

Jefferson County Board of Education — in some cases, funds

that have been earmarked for post-high school studies (see,

e.q.. Plaintiffs' Exhibit 16 introduced at August 17 hearing,

p. 2 [affidavit of Tamiko Johnson]).9 Moreover, should the

Attorney General interpose an objection to the proposed annexa

tions under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act, the Dolomite students

could be required to return to the Jefferson County school

system at some undetermined point after the school year has

begun, with an impact upon their educational progress and

social and emotional well-being which cannot be ascertained.

(c) On the other hand, Jefferson County will suffer no

injury if it continues to educate these students pending

plenary consideration and disposition of this appeal. The

county school system will continue to receive state and other

revenues for these students and obviously has adequate school

capacity to house them. See Brown v. Board of Education of

Bessemer. 808 F.2d at 1449.

(d) Finally, the public interest in maintaining public

school desegregation in Jefferson County, so painfully sought

over such a long period of time, is too obvious to require

9The court should bear in mind, in evaluating the equities,

that the Dolomite areas voted or petitioned for annexation into

the City of Birmingham after the City of Pleasant Grove refused

to annex them for racial reasons and withdrew vital fire and para

medic services from their residents.

13

elaboration. See Bob Jones University v. United States. 461

U.S. 574, 591-95 (1983).

12. Plaintiffs-appellants have not sought relief pending

appeal from the district court, because that court's refusal on

August 17, 1987 to grant a Temporary Restraining Order makes clear

the futility of seeking such relief.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs-appellants

respectfully pray that upon consideration of this motion and any

response[s] thereto which may be filed in such time as the Court

may direct, as well as the papers from the district court proceed

ings submitted herewith, this Court issue an injunction pending

disposition of this appeal on the merits which requires the appellee

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION to provide public educational

services to all schoolchildren now or hereafter residing in the

areas of the "Dolomite" community of Jefferson County that are

eligible to become annexed to the City of Birmingham, Alabama

upon pre-clearance by the Attorney General under § 5 of the voting

Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c.

Respectfully submitted

Of Counsel:

DONALD V. WATKINS

Watkins, Carter & Knight

1120 South Court Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

(205) 262-2723

OSCAR W. ADAMS, III

729 Brown Marx Tower

2000 1st Avenue N.

(205) 324-4445 JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

- 14

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned counsel of record certifies that the following

listed persons and bodies have an interest in the outcome of this

Hon. Sam C. Pointer, Jr., United States District Judge

Linda Stout, Regina Vann, Kimberly Nicole Gates, Veronica

Walker, Tamiko Johnson, et al., and the class of black school-

children residing in Jefferson County, Alabama, attending the

public schools of Jefferson County, Alabama, or eligible to attend

the public schools of Jefferson County, Alabama, and their parents

The United States of America

The Jefferson County Board of Education; Jim Hicks, Mrs.

Harriette W. Gwin, Mrs. Mary Buckelew, Mrs. Ordrell Smith, and

Dr. Kevin Walsh, as members of the Jefferson County Board of Edu

cation; and Dr. William E. Burkett, as Superintendent of Schools

of Jefferson County, Alabama

The City of Birmingham, Alabama; and the Hon. Richard

Arrington, Jr., as Mayor of the City of Birmingham

Donald v. Watkins and Watkins, Carter & Knight; Oscar W.

Adams, III; Julius L. Chambers and Norman J. Chachkin, as attorneys

for plaintiffs-appellants

Caryl Privett, Assistant United States Attorney, as attorney

for the United States of America

Carl Johnson, Jr., as attorney for the Jefferson County Board

of Education, its members and its Superintendent

Samuel Fisher, Assistant City Attorney, as attorney for the

City of Birmingham and its Mayor

case:

chachkin

•ney (for Plaintiffs

Appellants

August 24, 1987

15

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 24th day of August, 1987, I

served a copy of the foregoing Emergency Motion for Injunction

Pending Appeal and supporting papers upon the following counsel

for the other parties to this appeal, by delivering the same to

an agent of Federal Express, for prepaid next-day delivery to

each of them as follows:

Carl Johnson, Jr., Esq.

603 Frank Nelson Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Caryl Privett, Esq.

Assistant United States Attorney

200 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Samuel Fisher, Esq.

Assistant City Attorney

710 North 20th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203