NAACP Lawyers File Segregation School Answers with Supreme Court

Press Release

November 16, 1953

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. NAACP Lawyers File Segregation School Answers with Supreme Court, 1953. e55882cc-bb92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cab17aab-d686-4560-8c49-92d3360406ea/naacp-lawyers-file-segregation-school-answers-with-supreme-court. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

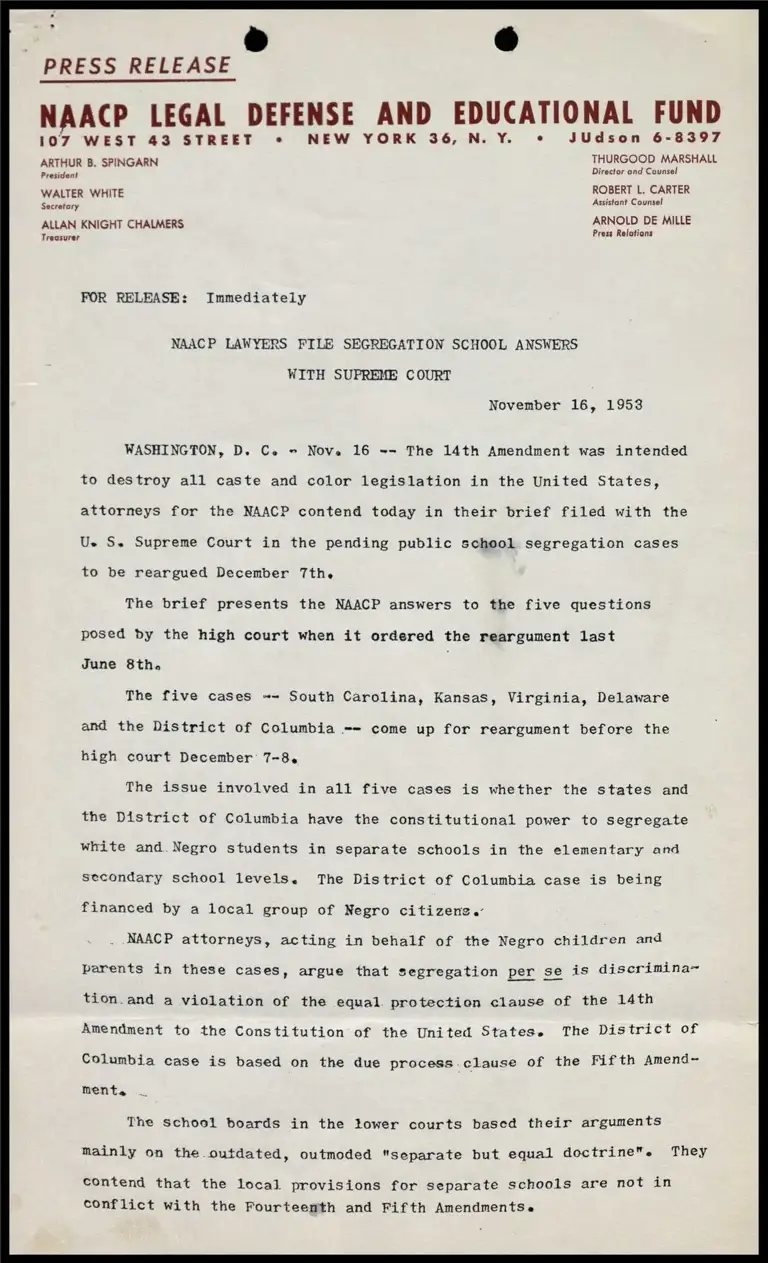

PRESS RELEASE

NA ACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

107 WEST 43 STREET * NEW YORK 36, N. Y. ¢© JUdson 6-8397

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director and Counsel

WALTER WHITE ROBERT L. CARTER

Secretary Assistant Counsel

ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS ARNOLD DE MILLE

r Press Relations recsurer

FOR RELEASE: Immediately

NAACP LAWYERS FILE SEGREGATION SCHOOL ANSWERS

WITH SUPREME COURT

November 16, 1953

WASHINGTON, D. Ce = Nove 16 -- The 14th Amendment was intended

to destroy all caste and color legislation in the United States,

attorneys for the NAACP contend today in their brief filed with the

Ue S. Supreme Court in the pending public school segregation cases

to be reargued December 7the

The brief presents the NAACP answers to the five questions

posed by the high court when it ordered the reargument last

June 8th.

The five cases =~ South Carolina, Kansas, Virginia, Delaware

and the District of Columbia -- come up for reargument before the

high court December 7-8.

The issue involved in all five cases is whether the states and

the District of Columbia have the constitutional power to segregate

white and.Negro students in separate schools in the elementary and

secondary school levels. The District of Columbia case is being

financed by a local group of Negro citizeng.

NAACP attorneys, acting in behalf of the Negro children and

parents in these cases, argue that segregation per se is discrimina~

tion.and a violation of the equal. protection clause of the 14th

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. The District of

Columbia case is based on the due process clause of the Fifth Amend~

ments

The school boards in the tower courts based their arguments

mainly on the outdated, outmoded "separate but equal doctrine". They

contend that the local provisions for separate schools are not in

conflict with the Fourteenth and Fifth AmendmentSe

er

es

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Questions One and Two:

1. What evidence is there that the Congress which submitted

and the State legislatures and conventions which ratified the

Fourteenth Amendment contemplated or did not contemplate, under-

stood or did not understand, that it would abolish segregation in

public schools?

2. If neither the Congress in submitting nor the States in

ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment understood that compliance with

it would require the immediate abolition of segregation in public

schools, was it nevertheless the understanding of the framers of

the Amendment.

(a) that future Congresses might, in the exercise of their

power under Sec. 5 of the Amendment, abolish such segregation,

or

(b) that it would be within the judicial power, in light

of future conditions to construe the Amendment as abolishing

such segregation of its own force?

Answers to Oné and Two:

"There iSsample evidence that the Congress which submitted

and the states which ratified the 14th Amendment contem-

¢ “pkated and understood that the amendment would deprive

the states of the power to impose any racial distinctions

in determining when, where and how its citizens would en-

joy the various civil rights afforded by the states," it

is argued in the brief." . . .the right to public school

education was one of the civil rights with respect to which

the states were deprived of the power to impose racial

distinctions."

The framers of the 14th Amendment were men... with

a well defined background of Abolitionist doctrine dedi-

cated to the "“equalitarian principles of real and complete

equality for all men," the lawyers cited.

The era prior to the Civil war was marked by determined

efforts to secure recognition of the principle of complete

3.

and real equality for all men within the existing constitutional

framework of our Government."

NAACP attorneys stated that the 39th Congress, framers of the

14th Amendment, "were formulating a constitutional provision setting

broad standards for determination of the relationship of the state

to the individual", but could not list all of the specific categories

of existing and prospective state activity which were to come with~

in the constitutional don'ts.

"In short," NAACP lawyers argue, "the 14th Amendment was

designed to take from the states all power to enforce caste or class

distinctions."

The evidence as to the understanding of the states is equally

convincing, the brief points out. The amendment was ratified in

1868 by the states, 18 years before the "separate but equal"

doctrine came into existence.

The lawyers for the Negro students say that the state is with-

out power to “enforce distinctions based upon race or color in

affording educational opportunities" in the public school.

Question 3:

On the Assumption that the answers to questions 2 (a) and (b)

do not dispose of the issue, is it within the judicial power, in

construing the Amendment, to abolish segregation in public schools?

Answers to 3:

"This Court (Supreme Court) in a long line of decisions has

made it plain that the 14th Amendment prohibits a state from making

racial distinctions in the exercise of governmental power."

The Supreme Court has held time and again that if the state's

power has been exercised in such a way as to deprive a Negro of a

right which he would have freely enjoyed if he had been white, then

that state's action violated the 14th Amendment.

"This Court has made it plain that no state may use color or

race as the axis upon which the state's power turns, and the con-

duct of the public education systems has not been excepted from the

ban," they arguee

ote @

Questions 4 and 5

4, Assuming it is decided that segrepation in public schools

violates the Fourteenth Amendrent,

(a) would a decree necessarily follow providing that, within

the limits set by normal geographic school districting, Negro

children should forthwith ke admitted to schools of their

choice, or

(b) may this Court, in the exercise of its equity powers,

permit an effective gradual adjustment to be brought about

from existing segregated systems to a system not based on

color distinctions?

5. On the assumption on which questions 4(a) and (b) are

based, and assuming further that this Court will exercise its equity

powers to the end desecrived in question 4(b),

(a) should this Court formulate detailed decrees in these

cases3

(b) aif so what specific issues should the decrees reach}

(c) should this Court appoint a special master to hear

evidence with a view to recomrending specific terms for

such decrees;

(d) should this Court remand to the courts of first instance

with directions to frame cecrees in these cases, and,

if so, what general directions should the decrees of

this Court include and what procedures shovld the courts

of first instance follow in arriving at the specific

terms of more detailed decrees?

Answers 4 and 5:

The attorneys contend that the Court does have the power to

rule that segregated schools violate the 14th Amendment and know

no reason why the Court should postpone its decision.

They call on the Court to abolish the segregated school

system and issue a decree immediately.

"In accordance with instructions of this Court we have addressed

ourselves to all of the plans for gradual adjustment which we have

been able to find, None would be effective,

"In the absence of any such reasons the only specific issue

which appellants can recommend to the Court that the decrees

should reach is the substantive one presented here, namely, that

ate

appellees should be required in the future to discharge their

obligations as state officers without drawing distinctions based

on race and color. Once this is done not only the local communi-

ties involved in these several cases, but communities throughout

the South, would be left free to work out individual plans for

conforming to the then established precedent free from the

statutory requirement of rigid racial segregation."

"These rights are personal because each appellant is assert-

ing its individual constituticnal risht to grow up in our

democratic society without impress of state-imposed racial segre-

gation in the public schools," the attorneys asserted.

The NAACP conclusion states:

"Under the applicable decisions of this Court the state

constitutional and statutory provisions herein involved are clearly

unconstitutional, horeover, the historical evidence surrounding

the adoption, submission and ratification of the Fourteenth Amend~

ment compels the conclusion that it was the intent, understanding,

and contemplation that the Amendment proscribed all state imposed

racial restrictions, The Negro children in these cases are

arbitrarily excluded from state public schools set apart for the

dominant white groups, Such a practice can only be continued on a

theory that Negroes, qua Negroes, are inferior to all other Ameri-

cans. The constitutional and statutory provisions herein challenged

cannot be upheld without a clear deterwinaticn that Negroes are

inferior and, therefore, must be segregated fror other human beings,

Certainly, such a ruling would destroy the intent and purpose of the

Fourteenth Amendment and the very equalitarian basis of our Govern-

ment,"

(More)

= 1G a:

The reargument was originally scheduled before the United

States Supreme Court on October 12, but was postponed at the request

of the Attorney General who asked for an extension of time.

The filing of the 240-page brief, with 525 footnotes brings to

an end twenty-two hectic weeks of intensive research and study on

the part of 130 lawyers and experts scattered across tie country,

headed by Thurgood Narshal1, NAACP Special Counsel and Director of

the Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., and his assistant,

Robert L. Carter.

Preparation of the brief was coordinated by the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund staff consisting of Constance Baker Motley, Jack

Greenberg, Elwood Chisolm, David Pinsky, U. S. Tate, Daniel E,

Byrd, and June Shagaloff, with the assistance of Marvin Karpatkin

and Julia Baxter.

In addition to the staff, other attorneys and legal experts

who-'worked on the brief were: Charles L. Black, Jr., William T.

Coleman, Jr., Charles T. Duncan, George E. C. Hayes, George Hh.

Johnson, William R. Ning, Jr., James MN. Nabrit, Jr., Frank D. Reeves,

John Scott, Jack B. Weinstein, Charles S. Scott, Spottswood W.

Robinson, III, and Harold R. Boulware. Also Professor Walter Gell-

horn of Columbia University School of Law; Loren Miller, Los Angeles,

California; and Professor John Frank, Yale University School of

Lawe

Included among the other experts were Dr. John A. Davis,

associate professor of Government at City College of New York;

Dr. able Smythe, Economist, Shiga University, Hikone City, Japan;

Dr. Alfred H. Kelly, Professor of Constitutional History, Wayne

University; Howard Jay Graham, Law Librarian of Los Angeles County

Bar Association; Dr. Horace li. Bond, President of Lincoln University;

Dr. C. Vann Woodward, Professor of History, Johns Hopkins University;

Marion Wright, Professor of Education at Howard University, Dr. John

Hope Franklin, Professor of History at Howard University, Professor

Ben Kaplan, Harvard Law School; Dr. Milton R. Konvitz, Cornell

University and David Feller, of the C.1.0., Washington, D. C.

Also, Dr. Charles R. Wesley, President of Wilberforce Univer-

sity, Robert Kk, Carr, Professor of Political Science at Dartmouth

College; Dr. Howard K. Beale, Professor of History at the Univer-

sity of Wisconsin; Dr. Charles H. Thompson, Dean of Graduate

School at Howard University; Dr. Charles S. Johnson, President of

Fisk University; and Dr. Buell Gallagher, President of the City

College of New York.

Also Professor Kenneth Clark of City College of New York;

Dr. Rayford Logan, Howard University; Lillian Dabney, Baltimore,

Maryland.

Suan =